GOVERNMENT CONTROL OF THE INTERNET IN CHINA

Internet Police China, in the opinion of many, has the most extensive Internet censorship system in the world. The government has spent hundreds of of millions — perhaps billions — of dollars on filters and other blocking devices to prevent the spread of information over the Internet.Chinese dissident Fang Lizhi wrote in the New York Review of Books, “The regime’s curbs on the Internet range from filtering out large numbers of “sensitive” terms to simply unplugging the Web in an entire region for weeks on end. [Source: Fang Lizhi, New York Review of Books, November 10, 2011]

The powerful Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) watches over social media content in China and censors online information and blocks some websites. Established in May 2011, as subordinate a office under the powerful cabinet-like State Council, t establishes rules to govern content on the internet and sets up regulations that addresses problems that other countries also face, such as misinformation and online fraud. In 2018, the CAC launched the China Federation of Internet Societies (CFIS), a broad internet industry grouping whose stated purpose is to “promote the development of Party organizations in the industry.”

Michael Wines wrote in the New York Times, The mushrooming growth of China’s Internet business has spawned a sort of land rush for regulatory turf by government agencies that see in it a chance to gain more authority or more money, or both. At least 14 government units, from the culture and information technology ministries to offices that oversee films and books, have some hand in what appears on China’s Internet. Others have interests in Internet-related ventures like the sale of censorship software that could prove to be lucrative sources of income. More than 500 cities have established internet police bureaus. The Public Security Ministry has even introduced a male and female pair of characters in police uniforms that can pop up on person’s screen when a sensitive website is sought out to remind them their activities can be monitored. [Source: Michael Wines, New York Times, May 4, 2011]

Beijing encourages Internet use for education and business but tries to block Web surfers from seeing material deemed subversive or obscene. The government tries to block Internet users in China from seeing Twitter, Facebook and even Google and requires Chinese sites to confirm the identity of users. Beijing has a split personality toward the Internet. On one hand it wants to control it but on the other hand it relies on it, with almost all government agencies and city offices maintaining their own websites and often blogs, as well. Police stationsregularly use Twitter-like micro-blogs (“weibos”) for everything from citing crime statistics to publicizing social order campaigns. Just as important, the Internet has become key for Beijing to monitor what its citizens are concerned or riled up about, whether it’s official corruption or high property prices. “The government for a long time has recognized that the Internet is a place for citizens to let off steam but is also a platform that allows the government to get a read on what is going on across the country, in the provinces,” China expert Jeremy Goldkorn said. “But they have a tough time balancing that with their desire to ensure the Internet does not lead to instability, or to any kind of threat to their control.”

Rules Governing the Internet in 2020 include: 1) “Encouraged: Spreading and explaining Party doctrine, with “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” listed as priority number one; spreading the Core Socialist Values; and increasing China’s international influence. 2) Negative: Sensationalizing headlines; sexual innuendo, suggestion, or enticement; gore and horror; and incitement of discrimination. 3) Illegal: Content endangering national security, divulging State secrets, subverting the national regime, and destroying national unity; content demeaning or denying the deeds and spirit of heroes and martyrs; content promoting terrorism or extremism; and content inciting ethnic hatred or ethnic discrimination, or destroying ethnic unity, etc. [Source: SupChina, March 9, 2020]

INTERNET AND COMMUNICATIONS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) MCLC ; China Media Project cmp.hku.hk ; China Digital Times chinadigitaltimes.net ; Wikipedia article on Internet Censorship in China Wikipedia

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Great Firewall of China: How to Build and Control an Alternative Version of the Internet” by James Griffiths Amazon.com; “Censored: Distraction and Diversion Inside China's Great Firewall” by Margaret E. Roberts Amazon.com; “Blocked on Weibo: What Gets Suppressed on China s Version of Twitter (and Why)” by Jason Q. Ng Amazon.com; “Trafficking Data: How China Is Winning the Battle for Digital Sovereignty” by Aynne Kokas, Hannah Choi, et al. Amazon.com; “Surveillance State: Inside China's Quest to Launch a New Era of Social Control” by Josh Chin, Liza Lin, et al. Amazon.com; “We Have Been Harmonized: Life in China's Surveillance State” by Kai Strittmatter, Matthew Waterson, et al. Amazon.com

How the Government Controls the Internet in China

The Chinese government regulates the Internet through the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, created in 2008. The Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) is most powerful internet regulator. Before 2008, the Ministry of Information Industry regulated access to the Internet, and the Ministry of Public Security and the Ministry of State Security monitored its use. A broad range of topics that authorities interpret as potentially subversive or as slanderous to the state, including the dissemination of anti-unification information or “state secrets” that may endanger national security, are prohibited by various laws and regulations. Promoting “evil cults” (a term used for Falun Gong) is banned, as is providing information that “disturbs social order or undermines social stability.” Internet service providers (ISPs) are restricted to domestic media news postings and are required to record information useful for tracking users and their viewing habits, install software capable of copying e-mails, and immediately abort transmission of material considered subversive. As a result, many ISPs practice self-censorship to avoid violations of the broadly worded regulations. [Sources: Wikipedia, Library of Congress, August, 2006]

China constantly strives to exert its control over the Internet, blocking content it deems politically sensitive as part of a vast censorship system. A special 30,000-member police unit checks chat lines, looks for spikes in Internet traffic, monitors and screens websites and blogs for sensitive material and blocks access to violators. Advanced technology is deployed to block access to overseas websites regarded as threatening. China has purchased much of its filtering and spying equipment from the American companies like Cisco Systems and Dynamic Internet technology.

Both domestic and foreign providers must comply with restrictions designed to suppress political dissent and track down offenders. Each week representatives of China’s most popular websites are summoned to the Internet Propaganda Management Department and are told which news they should keep off their services. As of early 2007, the government had shut down more than 700 online forums and websites and blocked more than 10,000 sites. including thousands of popular news, political and religious sites. Access to business, cultural, and educational sites is generally no a problem because Beijing views access to them as essential for being part of the globalized world. A specific “ideological education” campaign was launched against student websites used by million to discuss a wide range of topics, including pop culture and politics. The government has even conducted tests to explore how “harmful information” can be expunged quickly from the Internet in the event of an “emergency.”

Government Control of Internet Users in China

Internet users in China are supposed to register with police and sign an agreement promising not to harm the country or do anything illegal. Internet police” can jam e-mails viewed as threatening, tap the Internet the same way it does telephone lines, and monitor Internet users who type in word like "Taiwan" or "Falun Gong" in their e-mail accounts.

Most users don't care about blocked sites so much. They aren’t that interested in politics and when they do view an illegal site is most likely to be a pornographic one. One survey found that four out of five Chinese want the Internet to be controlled mainly out of concern about pornography. As long as Chinese users have access to the chat lines and games they like they are happy. The government makes no secret about its intention to block sites. Most Internet-related businesses are willing to comply and the government even hands out wards to those that do the job eagerly and efficiently. The owner of one large Internet company told the New York Times, “We don’t want to annoy the government.”

Some users however upset. Reuters described one Internet user who was unable to access his friend’s holiday photographs on Flickr.com, because Flickr.com had been blocked for showing images of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre. Wikpedia and a number of seemingly harmless blogs have also been blocked. In the past and still to some extent today, almost as quickly as sites are blocked links to browser plug ins and other methods to subvert the filters are posted on blogs and in chart rooms.

The Chinese government has been accused of forcing foreign hotels to install Internet filters on computers in the hotels that allow the government to spy and eavesdrop on Internet uses at the hotel. Among the ideas proposed at the 2010 National People’s Congress to improve security were placing all the country‘s Internet cafes under government control and installing surveillance cameras in all cell phones,

The Chinese government has tried to require users to register using their real names and prevent them from using anonymous names which they have traditionally relied on to mask their identity so they can speak freely without persecution. Police reportedly have access to software developed by Cisco that allows them to track people’s work histories and political tendencies. Much of the surveillance software is thought to have been developed by the Chinese themselves, much of it by engineers in the Chinese military.

Government Control of Web Sites and Search Engines in China

James Glanz and John Markoff wrote in the New York Times, “All major web sites that are authorized in China have to submit to security checks and are required to sign a code of conduct in which they promise to keep unauthorized content off their sites. Sites that "leak state secrets," contain pornography, or promote social disturbances can be shut down. Individuals that break laws risks being sent to prison for long sentences. [Source: James Glanz and John Markoff, New York Times, December 4, 2010]

Web sites run by BBC, the New York Times, Time Warner's Pathfinder, human right groups, Falun Gong, Tibetan exiles, pro-democracy groups, and Taiwan independence groups have been blacked out. A surprising number of sexually explicit sites are accessible, which is ironic because the government originally claimed that the primary point of censorship was to block them out.

In 2002, the government blocked access to Google. Google was popular among Chinese users because if its wide-ranging search capacity and the fact its links were unblocked and uncensored. In April 2004, the government began a crackdown on Internet discussion groups with new rules that banned independent reporting not be approved by the government, and prohibited discussions of sensitive issues such as economic failures and criticism of the Chinese Party.

In December 2004, the government Internet watchdog agency the Center of Illegal and Harmful Information shut down 1,287 We sites because they spread “harmful information” on religious cults, superstition and pornography. Some of the sites were shut down after the government was alerted by informants paid between $60 and $240.

In September 2005, the Chinese government stepped up its crackdown on “unhealthy” sites and news sites were required websites to register with the State Council or with provincial-level government information offices. Bloggers were forbidden from post information that “creates social uncertainty.” In January 2007, Chinese President Hu Jintao ordered Internet regulators to promote “healthy online culture” and “purify the Internet environment.”

Control on the Internet Stepped Up After Protests in 2009 and 2011

Internet controls ramped up in late 2009, when officials observed how social networking sites and other forums helped inflame unrelated outbursts of protests and rioting in Iran and Xinjiang, the restive region in China’s west. In August 2009 article on the Iran protests in a monthly journal published by the central propaganda department warned of the challenge posed by sites like Twitter and Facebook, which the authorities had blocked days after riots in Xinjiang. The Internet’s influence on the volatile events in Iran and Xinjiang “impacted the leadership like an earthquake,” said one media investor with high-level ties to China’s regulators

Jasmine Revolution Protest in

Beijing organized through the Internet

and Twitter-like microblogs

In February and March 2011, after the so-call Jasmine Revolution “protests” in several Chinese cities, the Chinese government appeared to step up its censorship of electronic media. At the time Sharon Lafraniere wrote in the New York Times, “A host of evidence shows that Chinese authorities are more determined than ever to police cellphone calls, electronic messages, e-mail and access to the Internet in order to smother any hint of antigovernment sentiment. In the cat-and-mouse game that characterizes electronic communications here, analysts suggest that the cat is getting bigger, especially since revolts began to ricochet through the Middle East and North Africa, and homegrown efforts to organize protests in China began to circulate on the Internet in February. about a month ago. [Source: Sharon Lafraniere, New York Times, March 21, 2011]

A Beijing entrepreneur, discussing restaurant choices with his fiancée over their cellphones quoted Queen Gertrude’s response to Hamlet from the Shakespeare play: “The lady doth protest too much, methinks.” The second time he said the word “protest,” her phone cut off. He spoke English, but another caller, repeating the same phrase in Chinese over a different phone, was also cut off in midsentence.

“Google accused the Chinese government of disrupting its Gmail service in the country and making it appear as if technical problems at Google — not government intervention — were to blame, Lafraniere wrote. “Several popular virtual private-network services, or V.P.N.’s, designed to evade the government’s computerized censors, have been crippled. This has prompted an outcry from users as young as ninth graders with school research projects and sent them on a frustrating search for replacements that can pierce the so-called Great Firewall, a menu of direct censorship and “opinion guidance” that restricts what Internet users can read or write online. V.P.N.’s are popular with China’s huge expatriate community and Chinese entrepreneurs, researchers and scholars who expect to use the Internet freely. In an apology to customers in China for interrupted service, WiTopia, a V.P.N. provider, cited “increased blocking attempts.” No perpetrator was identified.

Sites Blocked by the Chinese Government

In 2009 the Chinese government closed down hundreds of video sharing sites and ordered sites to delete all links to sites that download films and television series, In September 2009, the Chinese government announced that every foreign and domestic song posted in music websites needed prior approval, and foreign music providers have to provide Chinese translations for all the songs they post. As of November 2009, 414 video and audio websites had been shut down for operating without a license or containing pornography, copy-violating content to other “harmful” information.

The uprisings in Tibet in 2008 and Xinjiang in 2009 prompted a fresh wave of Internet restrictions with more attention being focused in social networking sites like Twitter and Facebook. In March 2009, YouTube has was blocked the Chinese government. It was not clear why this was done but some thought it might have been done because of the showing of a fabricated video that showed Chinese officers brutally beating Tibetans. The government routinely blocks individual videos on YouTube but rarely blocks the whole site

Twitter and Flickr were blocked on the eve of the 20th anniversary of Tiananmen Square crackdown in 2009. Wikipedia has been repeatedly blocked and unblocked. Facebook has also been blocked. In October 2008, it was revealed that Skype messages were monitored and stored by Skype’s Chinese venture TOM-Skype and the information could be accessed by the government. Links to Wikileaks were blocked in late 2010 when the site released its plethora of embarrassing documents. Wikileaks founder Julian Assange said the Wikileaks was getting past Chinese censors.

The Chinese government says that it has the right to block sites that break its laws for things like recognizing the existence of Taiwan or supporting Falun Gong, democracy movements, Tiananmen Square or the Dalai Lama. In December 2008, a few days after defending its right censor online content deemed illegal, the Chinese government blocked access to the New York Times website. The BBC has complained that the government blocks access to its Chinese-language site BBC Chinese .com.

Beijing is particularly aggressive in its crackdowns of pornography. In January 2009, the Chinese government shut down 91 web sites deemed pornographic and vulgar and one political blog portal. In December 2009, authorities began offering reward up to almost $1,500 to Internet users who report websites that feature pornography and set up rulers for domain registration to curb pornography.

In 2016, China has shut down several online news operations amid a crackdown on political and social news reporting. The BBC reported: “News services run by some of China's biggest online portals, including Sina, Sohu, NetEase and iFeng, were shut for publishing independent reports instead of official statements. Major online news columns, such as Sina's News Geek, Sohu's Click Today, and NetEase's Signpost were closed because they had "published large amounts of independently-gathered news reports, in serious violation of the rules" the state newspapers Beijing Daily and the Beijing News reported. [Source: BBC, July 25, 2016]

Great Firewall of China

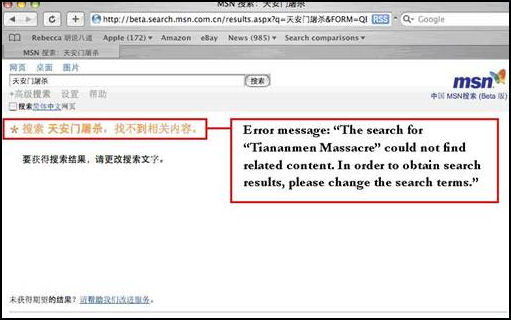

The Great Firewall of China is a term used to describe the blocking of websites and parts of websites by the Chinese government's Golden Shield infrastructure. Filtering systems referred as the Great Firewall of China work by blocking access to sites with keyword like Tibet, democracy, Tiananmen Square, Taiwan independence, sex, Dalai Lama, human rights, Amnesty International, or Falun Gong. If you type the words “democracy” or “freedom,” for example, on the MSB Spaces Web log service — a blogging service — you get the message: “You must enter a title for your space. This title must contain prohibited language, such as profanity. Please type a different title.”

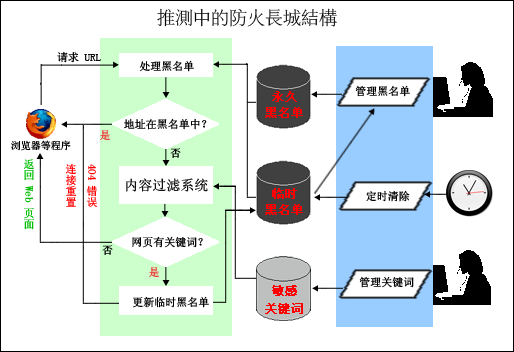

The primary Firewall barriers are: 1) the Domain Name System (DNS) block, which prevents users from locating entire websites and addresses based on the domain name; 2) disrupting the “connect phase,” which prevents users form connecting with certain blacklisted sites by impeeding their ability to connect with them; and 3) the URL keyword block, which prevents users from connecting with certain sites or articles that have blacklisted keywords.

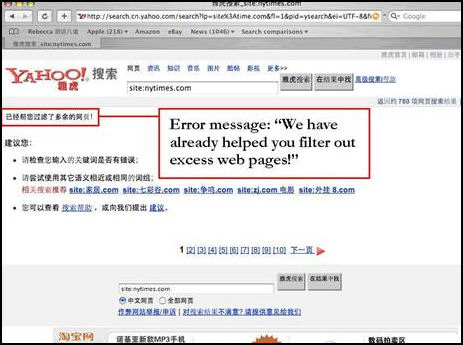

Much of the blocking of the Internet by the Chinese government is done by disrupting the “connect phase,” and with the URL keyword block in this way: 1) a user enters a URL (address) to a browser; 2) the monitoring system checks whether the URL is on a blacklist (if it is the user is sent an error message); 3) filtering systems check whether the text on the URL requested contains flagged terms (again if it does the user is sent an error message). There are also filers that screen e-mail and search engine request.

The URL keyword block can block an entire site with the blacklisted keyword or only a part of the site or an article with the blacklisted keyword. With this system users are punished with broken connections and display of the message “the connection has been reset.” The broken connections can last more than a hour if a user repeatedly tries to access a certain blacklisted keyword. If the offense continues further the Internet police can be alerted and they may try to locate the user The surveillance system is constantly being updated with new keywords added all the time.

Father of Firewall Pelted Online and In Person

A computer scientist named Fang Binxing is seen as the father of China's "Great Firewall". A microblog her opened was forced offline by angry comments within a few hours of opening. Anonymous posters peppered the microblog of with hundreds of caustic or sarcastic comments, and eventually all of Mr Fang's posts and the responses were taken down. Then the same sort of thing happened in person. In May 2011, Fang, , the principal of Beijing University of Posts & Telecommunications, was pelted with eggs and a shoe while giving a lecture at Wuhan University.

China Want Times reported: “While the eggs launched at Fang seem to have missed, the shoe thrown by a female student allegedly struck its target. Though reports of the attack have not been confirmed, netizens in China reposted the news widely online soon after and online encyclopedia Wikipedia has listed the incident in Fang Bingxing's entry. [Source: Want China Times May 19 2011]

Fang is known for his substantial contribution to China's internet censorship infrastructure. He began working at the National Computer Network Emergency Response Technical Team/Coordination Center of China in 1999 as deputy chief engineer and from 2000 he served as chief engineer and director. It was in this position that he oversaw the development of the filtering and blocking technology that has become known as China's "Great Firewall."

Internet users regard Fang as an enemy who has stripped netizens of the ability to view and download online content freely. After hearing that Fang was due to give a lecture at Wuhan University, netizens jokingly offered rewards to whoever could successfully pelt him with an object. Rewards on offer included a DVD of Japanese porn star Sora Aoi, one night at a five star hotel in Hong Kong, one large hug, a round trip air ticket to Shanghai, a week in California, or one night stand with the person offering the prize. It is believed all the rewards mentioned are genuine.

Routers and the Green Dam

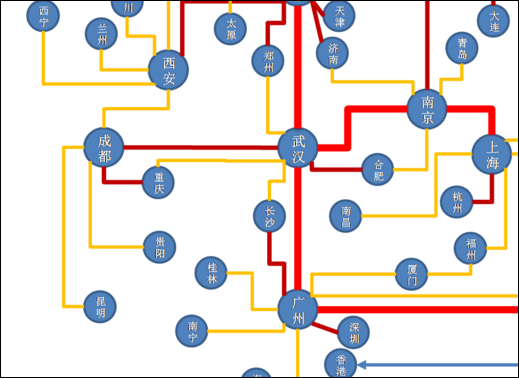

The blocking and surveillance systems that the Chinese use rely on routers — switches located where fiber optic cables cross international borders. All Internet connections between China and the rest of the world are routed through a relatively small number of optic cables at one of three points: 1) the Beijing-Tianjin Qingdao connection in north, where cables come in from Japan; 2) the Shanghai connection on the central coat, where cables also come in from Japan; and 3) the Guangzhou connection in the south, where the cables come in from Hong Kong. There are some lines that run through Central Asia and Russia but they carry little traffic. An illustration of how fragile this system is came in 2006 when an earthquake around Taiwan that cut some major sea cables into China, disrupted international transmissions to and from China for weeks.[Source: James Fallows, The Atlantic, March 2008]

The Chinese are able to monitor Internet traffic by installing monitoring devises at the “international gateways” into China. Using a technique called “mirroring” that does incorporate extremely small mirrors, information that travels through the gateways is copied and sent with mirroring routers to “Golden Shield” computers which sort through the data and determine if anything should be blocked. The mirror routers — many designed by Cisco — can be used to eavesdrop on transmissions. If the transmissions pick up something deemed offensive — a key word for example — the transmission can be blocked, Some of the systems are quite sophisticated and block only certain parts of transmissions and let others through. With a site like CNN or BBC, sports may be allowed to pass through while the news is blocked. When a site is blocked an error message appears.

Guess Great Firewall Mechanism

In 2009, the Chinese government released a controversial web filtering software called Green Dam-Youth escort. The original plan called for it to be installed on all computers put on sale but this requirement deeply angered both domestic and international computers makers. Users voiced their anger in forums and blogs and circulated petitions condemning the plan and called for a boycott of the Internet on the day the filter was introduced, July 1, 2009.

Green Dam critics claimed the system could be used to monitor user web-surfing activities and condemned how the contract to run it was given without open bidding to two little-known software firms with military connections. In the end the system was only installed on computers in public places such as schools and Internet cafes and consumers were given the choice of whether or not to have it installed on new computers they purchased. The government said the primary purpose of the software was to filter out violent and pornographic content to protect youths but many felt the filter would used to block any site the government disapproved of.

Blocking Sites Within China

Internet users and sites with China poses a numbers problem for censors. Unlike the use of the Great Firewall to block foreign information from entering China, data within China “cannot be choked off at a handful of gateways. So the government employs a number of controls, including persuasion, co-option, force, self-censorship, filtering and regulations and obligations placed on all network and site operators in China.[Source: Michael Wines, Sharon Lafraniere and Jonathan Ansfield, New York Times, April 7, 2010]

According to the New York Times: “China’s big homegrown sites, like Baidu, Sina.com and Sohu, employ throngs of so-called Web administrators to screen their search engines, chat rooms, blogs and other content for material that flouts propaganda directives. The Internet companies’ employees are constantly guessing what is allowed and what will prompt a phone call from government censors. One tactic is to strictly censor risky content at first, then gradually expand access to it week by week, hoping not to trip the censorship wire.

“The monitors sit astride a vast and expanding state apparatus that extends to the most remote Chinese town. There is an Internet monitoring and surveillance unit in every city, wherever you have an Internet connection, said Xiao Qiang, an analyst of China’s censorship system, at the University of California, Berkeley. Through that system, they get to every major Web site with content.”

“Under a 2005 State Council regulation, personal blogs, computer bulletin boards and even cellphone text messages are deemed part of the news media, subject to sweeping restrictions on their content. In practice, many of those restrictions are spottily applied. But reminders that someone is watching are pointed and regular.An inopportune post to a computer chat forum may produce a rejection message chiding the author for inappropriate content, and the link to the post may be deleted. Forbidden text messages may be delivered to cellphones as blankscreens.”

Blocking Teletubbies and Winnie the Pooh

When words are blocked Internet users quickly get around the intrusions by using codes and puns. Under these circumstances Wen Jiabao, former, Chinese premier was give the nickname “teletubbies” while disgrced city leader Bo Xilai was referred to as “tomato/” Xi Jinping was called Winnie the Pooh

Tea Lea Nation reported: The most censored post in 2015 “consisted of four characters — “a picture to share” — and a photograph of a plastic Winnie the Pooh toy car. Shared 65,000 times in the 69 minutes before it was deleted — or fifteen times per second — this image used the amiable Pooh Bear as a proxy for the portly Xi inspecting troops at a solemn parade marking the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II. According to Weiboscope, this marked a spike in censorship with 14.63 posts per 10,000 deleted in the run-up to the parade.

“The censorship of Pooh did not begin in 2015, but Pooh’s heightened sensitivity reflects the rise of Xi’s personality cult and his striking centralization of power. In this context, the bear of very little brain is an unwelcome counterpoint. The caricature may have been reasonably affectionate, but China’s authoritarian rulers, schooled in the art of control, fear losing command of their message. As George Orwell wrote, “Every joke is a tiny revolution.” [Source: Louisa Limm Tea Leaf Nation, Foreign Policy, December 31, 2015]

Internet Censorship in China

China’s Internet users are well accustomed to the daily manipulations of the Internet by censors in the form of shut-down blogs, dead links and inaccessible Web sites. The preferred euphemism for censorship is “guidance of public opinion.”

The list of banned keywords is a state secret. Sometimes a search for something as innocuous as “carrot” can result in a “blank screen.” Trying to figure out what is on it and what is not is often guesswork. In some cases some words that are banned in Chinese are available in English and visa versa. Carrot — in Mandarin, huluobo — used to be blocked because it contained the same Chinese character as the surname of President Hu Jintao. Even words that aren’t on list are effectively banned through self censorship and fear. David Bandurski, an expert on China's media, a told the Los Angeles Times, “There are explicit bad words, but the system really works by instilling fear. The paranoia is more effective than blacking certain words.”

Barbara Demick wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “You don’t always know when you’re being censored.When searching a sensitive subject, you will be frustrated with a blank screen and a vague error message (“the connection to the server was reset while the page was loading: is the most common”) so you’re never quite sure you’ve hit the wall or some technical glitch really did cause the problem...Often the user who’s tried to search something blocked won’t be able to get back online for several minutes — the equivalent of a time-out for a naughty child.”

Self censorship is the rule on the Internet in China. Most blogs are hosted by large Internet companies. They know that if the government finds something wrong the government will hold them responsible and thus the Internet firms censor the blogs. Many websites censor themselves to avoid trouble. Those that originate in China must comply with local laws, get the necessary licences and put with threats to stay on line. Those that originate outside of China have to deal with filtering systems.

A typical warning from the Beijing Internet Information Administrative Bureau read: “Dear colleagues, the Internet of late has been full or articles and messages about the death of Shenzhen engineer, Hu Xinyu, as a result of overwork. All sites must stop posting articles on this subject, those have been posted about it already must be removed from the site, and, finally, forums and blogs must withdraw all articles and ,messages about this case.” [Source: James Fallows, The Atlantic, March 2008]

See Weibo Censors Under WEIBOS, CHINA'S TWITTER-LIKE MICROBLOGS factsanddetails.com

Great Firewall comic

Moderators and the 50-Cent Party

According to the New York Times: “The China censorship machine is part George Orwell, part Rube Goldberg: an information sieve of staggering breadth and fineness, yet full of holes; run by banks of advanced computers, but also by thousands of Communist Party drudges; highly sophisticated in some ways, remarkably crude in others.”[Source: Michael Wines, Sharon Lafraniere and Jonathan Ansfield, New York Times, April 7, 2010]

“Censorship used to be done solely the Communist Party’s central propaganda department, whose main task was to tell editors what and what not to print or broadcast. In the new networked China, censorship is a major growth industry, overseen — and fought over — by no fewer than 14 government ministries. China censors everything from the traditional print press to domestic and foreign Internet sites; from cellphone text messages to social networking services; from online chat rooms to blogs, films and e-mail. It even censors online games.”

In the early 2000s all bulletin board comments were funneled through moderators. Those that were deemed objectionable were never posted. By the mid 2000s, posts went online automatically with moderators watching rather than directing. Anything that seemed objectionable was quickly deleted. By the late 2000s, comment deemed objectionable were widely posted anyway, even on state-run bulletin boards using filter software or defeating censors by doing things like inserting a comma between “human” and “rights.”

Both nationalist and human rights concerns are largely driven through exchanges on Internet bulletin boards, text messages and e-mail.The government tries to sway opinion by paying part time workers to anonymously enter bulletin board discussions and monitor what people are saying and to manipulate opinion to the government’s side.

In the early 2010s, The government reportedly has 30,000 agents posting pro-Beijing messages that are paid by the word. The Chinese government trains and finances a group that infiltrates Chinese chat rooms and Web forums to combat anti-party discussions. Dubbed the “50-cent party” for the payments the group receives for each pro-government posting, they seek out popular bulletin boards and try to turn around discussions that might be critical of the Communist Party or the government.

The army of state censors can quickly cut off Internet users if they wander into disapproved sites. At Sina.com, one of China's largest online news sites, once 2,973 comments were posted on one controversial issue but only 849 were visible. The rest were blocked.

Ouwitting Censors and Vaulting the Great Firewall

More and more Chinese are taking measures to skirt the Great Firewall in a practice known as “fanqiang” (“vaulting the wall”). On the belief that the Communist Party controls China’s Internet Minxin Pei wrote in the Washington Post: In spite of its huge investments in technology and manpower, the Communist Party is having a hard time taming China’s vibrant cyberspace. While China’s Internet-filtering technology is more sophisticated and its regulations more onerous than those of other authoritarian regimes, the growth of the nation’s online population and technological advances (such as Twitter-style microblogs) have made censorship largely ineffective. The government constantly plays catch-up.; its latest effort is to force microbloggers to register with real names. Such regulations often prove too costly to enforce, even for a one-party regime. At most, the party can selectively censor what it deems “sensitive” after the fact. Whenever there is breaking news — a corruption scandal, a serious public safety incident or a big anti-government demonstration — the Internet is quickly filled with coverage and searing criticisms of the government. By the time the censors restore some control, the political damage is done. [Source: Minxin Pei, Washington Post, January 26, 2011;Minxin Pei, director of the Keck Center for International and Strategic Studies at Claremont McKenna College, is the author of “China’s Trapped Transition: The Limits of Developmental Autocracy.”]

People have figured out ways to get on-line despite government efforts. Blogs are an effective way to outwit censors. If they are blocked they can simply change servers. Some that are shut down by the government one day reappear a day later. One pro-democracy site was shut 38 times over a three year period but managed to figure out a way to reopen each time.

Some sites post stories at 5:00pm when most of the censorship bureaucrats leave work for home, milking the story for all they can before censor show up for work the next day. Sometimes officials who close down the site are identified and besieged and harassed with e-mails, text messages and phone calls from those angry that the site was shut down.

To outwit filters that block sites with words like “democratic” or “corruption” users and readers in chat lines and forums use code words. There is also software that helps users evade filters and gain access to blacklisted sites. When authorities take action to block sites, messages and e-mails are sent to alert users of the moves and tell them how to get around them.

Once a piece of news is revealed it can quickly be spread by e-mails, text-messages, chat lines and blogs in way that expands very quickly and exponentially. The government may respond by ordering web sites that post the offending news to be shut and scan e-mails but by that time the information is in so many places there is no way censor it completely.

China Cracks Down on VPN Use

Anyone who wants to get around the firewall can do so using one of two tried and true methods: 1) the proxy server, a way of connecting a computer inside China with a computer elsewhere, allowing signals with the data concealed inside it to enter China; and 2) the VPN, or virtual private network, which creates a private encrypted channel that relays information in a way the firewall can’t pick up. VPNs such as Freegate or Ultrasurf funnel web traffic through third-party computers, allowing users in China to gain access to sites that otherwise would be blocked..

According to the Guardian: "Normally traffic flowing over VPN connections is secure because it is encrypted, meaning that the Chinese authorities were unable to detect what content was flowing back and forth over it. A VPN connection from a location inside China to a site outside China would effectively give the same access as if the user were outside China. Sites including Twitter and Facebook are blocked in China; by using a VPN linked to an outside "proxy" which acts a conduit for links to other sites, a China-based internet user could access either site directly from their computer without the authorities being able to monitor them. But in May 2011, that appears to have changed. According to Global Voices Advocacy, a pressure group that defends free speech online, disruptions of VPN use in China follows new systems put in place in the "Great Firewall" — in fact monitoring software on the routers that direct internet traffic within and across China's borders. The new software appears to be able to detect large amounts of connections being made to overseas internet locations.[Source: Charles Arthur, The Guardian, May 15 2011]

VPNs began to boom in the mid-2000s. According to Bloomberg the Chinese government mostly ignored the phenomenon. If someone could afford a VPN, the reasoning went, then they were probably the kind of citizen that the Chinese government trusted to use one — middle-class, worldly and with a great deal invested in the stability of the system. As of 2017, nobody knew how many VPN accounts were active in China. But Twitter claimed 10 million Chinese users, and that's certainly a small subset of the total number of people who buy individual VPNs. At that times, a Google search for "China VPN" brought up dozens of options.

China outlawed the use of VPNs in 2018. In July 2017, the Chinese government had ordered telecommunications providers to block access to VPNs by February 2018. Bloomberg reported: “The Chinese government has been moving in this direction for a long time. But, up until this year, it seemed to have struck an uneasy balance between its desire to control information and the desires of its most educated and cosmopolitan citizens to engage with the rest of the world online. [Source: Adam Minter, Bloomberg, July 12, 2017]

In 2018, a software engineer in Shanghai was sentenced to three years in prison and fined US$1,400 after providing illegal VPNs to hundreds of customers since 2016, the People’s Court Daily reported. In 2017, Wu Xiangyang from the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region, received a five-and-a-half-year prison sentence and a IS$76,000 fine for selling VPNs since 2013 without a proper license.[Source: Jiayun Feng, SupChina, October 10, 2018]

In March 2020, a Chinese internet user was fined by authorities in the northern province of Shaanxi for a VPN. Radio Free Asia, reported: “The Hanbin district police department in Shaanxi’s Ankang city said on May 19 that it had fined a local man 500 yuan (US$74) for scaling the Great Firewall, a complex systems of blocks, filters and human censorship that limits what Chinese users can see online. [Source: Gao Feng,Radio Free Asia, May 21, 2020]

Accessing V.P.N Services in China in the 2020s

Peter Hessler wrote in The New Yorker: In my nonfiction class, a senior named Yidi profiled her V.P.N. dealer. That was the term Yidi used — it was like sourcing drugs. “I’ve been paying him on WeChat for a while, so I want to find out who he is,” she told me, when she proposed the project. The dealer agreed to an interview, at which point Yidi learned that he was neither a hardened criminal nor a tech guy. He had developed an online course in art history after attending graduate school in Europe, where he became accustomed to a free Internet. After returning to China, he shopped around for a V.P.N. service and realized how easy it would be to set up such a business. That was an old story: the user who becomes a dealer.

“When Yidi asked how much the business cost to run, the dealer responded, “If I tell you, you will probably ask for a refund.” But he went ahead: for three hundred yuan a year, a little less than fifty dollars, he could rent a Vultr virtual private server overseas, which could handle up to fifty Chinese customers, each of whom paid the dealer an annual subscription fee of three hundred yuan. And then he scaled it up: fifty times three hundred, minus the minimal overhead, as many times as he pleased.

Yidi was one of the best writers in the class, with a breezy, funny voice. Her story had no sense of surprise or outrage — students seemed accustomed to contradictions and mixed messages. They weren’t shocked that the university required classes in Xi Jinping Thought while tacitly encouraging students to contract with illegal-V.P.N. dealers, just as they weren’t shocked when one of those dealers turned out to be somebody with a sideline in art history.

Yidi wrote: The business is operated on WeChat, one of the most meticulously monitored social-media platforms in the world, and I was concerned that such an approach is tantamount to distributing anti-sexual harassment leaflets on public transportation during International Women’s Day. But my dealer dispelled the myth. “Hundreds of millions of Chinese are getting around the wall, you think the state will punish them all?”

The dealer was exaggerating the numbers, but his point was that the Party wants some porousness in the firewall. People in the export business need to access Google Trends and other useful tools, and scholars and researchers depend on full access to the Internet. Yidi thought that more than half the students she knew at Sichuan University used a V.P.N., which was similar to other estimates I heard. In society at large, the figure is much lower, especially among older people. In 2017, when I surveyed a group of my former Fuling students, I asked whether they used V.P.N.s, and only one out of thirty responded in the affirmative. For most Chinese, the hassle and the expense act as deterrents. But it’s much more common among the young and the élite. Yidi’s dealer told her, “It’s a good business, the gray market of China.”

Image Sources: Human Rights Watch, Wiki Commons, Human Rights in China,

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2022