CUI JIAN

Cui Jian is widely regarded as the father of Chinese rock music and today remains China's most popular rock star. Known for blending Western and Chinese instruments with veiled political lyrics, he is periodically banned from appearing on television and and his concerts are often canceled at the last minute. He is popular in Southeast Asia, Hong Kong and Taiwan as well as the mainland and has played concerts in Europe and the United States. [Official website: cuijian.com ]

Cui (born 1961) is of Korean-Chinese descent and is a classically-trained trumpeter. He wrote in Time, "My musical odyssey began early. My father, a trumpeter in the People's Liberation Army, began teaching me when I was 14. My taste were strictly classical." In 1981 he joined the Beijing Symphony Orchestra and played trumpet in it for seven years. During the Cultural Revolution he performed with the Beijing Song and Dance Troupe; in the 1980s, he recorded an album of Hong-Kong-style pop songs. Cui said in an interview,”In '81 I became part of a song and dance troupe in Beijing, which eventually became the Beijing Symphony Orchestra. After '87 I left the orchestra.”

"Things began to change in 1985...when the group Wham! gave a concert in Beijing,” Cui wrote. “A year later I heard my first Beatles tape. I learned to play the electric guitar." In 1986 "I formed a band and made rock my life." In the late 1980s, he developed his distinctive style after being introduced to New wave artists like The Police and Talking Heads.

His groundbreaking album, “Rock on the New Long March”, attacked the party with clever between-the-line lyrics, and featured a unique sound that merged rock with traditional Chinese zheng and suona music. Some of his later music was influenced by xibie feng. Among his other albums are “Power to the Powerless” and “Egg Under the Red Flag”.

On music Cui said in an interview, “I think purely coming together in music is a little superficial, it's just a skill. This is easy to do and many people in China are like that. They put Chinese opera together with Western arrangements. But what they come out with is not all that. It's a little empty and commercial. I think a real coming together is the coming together of culture. Chinese young people understanding more about the West, and Western young people understanding more about China. The two cultures mutually understanding and mutually influencing. I think a real combination is in content, not form, and in the mind.”

See Separate Articles: MUSIC, OPERA, THEATER AND DANCE factsanddetails.com POP MUSIC IN CHINA: SHANGHAI JAZZ IN THE 1920s TO K-POP IN THE 2020s factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE POP MUSIC INDUSTRY factsanddetails.com BIG CHINESE POP ARTISTS: FAYE WONG, LUHAN AND THE FOUR KINGS OF HONG KONG factsanddetails.com ; ROCK IN CHINA: HISTORY, GROUPS, POLITICS AND FESTIVALS factsanddetails.com ; PUNK ROCK AND UNDERGROUND MUSIC SCENE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HIP HOP AND RAP IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; WESTERN POP MUSIC IN CHINA: WHAM, BJORK, THE STONES factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: 2009 Wall Street Journal article about Beijing Underground scene online.wsj.com ; ; 2009 New York Times article on Hip Hop nytimes.com Foreign Policy article on Underground bands foreignpolicy.com Chinese Pop Music Inter Asia Pop interasiapop.org; Sinomania, with old postings but still online sinomania.com ; Wikipedia article on C-Pop Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on Cantopop Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on Mandopop Wikipedia ; Chinese, Japanese, and Korean CDs and DVDs at Yes Asia yesasia.com and Zoom Movie zoommovie.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS AND MUSIC: “Cui Jian: Rock and Roll on the New Long March Road” by Cui Jian (CD) Amazon.com “Never Turning Back” by Jian Cui (poetry book) Amazon.com; “Like a Knife: Ideology and Genre in Contemporary Chinese Popular Music” (Cornell East Asia Series) by Andrew F. Jones Amazon.com; “The Evolution of Chinese Popular Music” by Ya-Hui Cheng Amazon.com ; “Red Rock: The Long, Strange March of Chinese Rock & Roll” by Jonathan Campbell Amazon.com “Beijing Underground: Cracks on a Great Rock Wall” by David James Hoffman Amazon.com; “Rocking China: Music Scenes in Beijing and Beyond” by Andrew David Field Amazon.com; “Music in China: Experiencing Music, Expressing Culture (Includes CD) by Frederick Lau Amazon.com; The Very Best Of Chinese Music by Han Ying, Various Artists, et al Amazon.com; “The Music of China's Ethnic Minorities” by Li Yongxiang Amazon.com; “Music, Cosmology, and the Politics of Harmony in Early China” by Erica Fox Brindley Amazon.com; “Chinese Music and Musical Instruments” by Qiang Xi (Author), Jiandang Niu Amazon.com

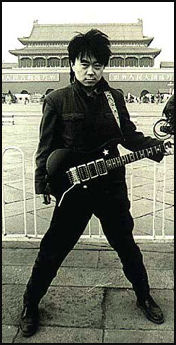

Cui in the 1980s

Dutch Sinologist and musician Jeroen den Hengst was part of the Beijing rock scene when it came to life in the late 1980s. He said: ““I arrived in China in September 1987 when the famous Beijing musician Cui Jian was just getting big. I came to China to study at Peking University as part of my Sinology studies at Leiden University, but soon ended up more in the Beijing music scene than I was in class. Singer Cui Jian got together at the time with Eddy [Randriamampionona] from Madagascar and drummer Zhang [Yongguang]. They would perform in Ritan Park with their band Ado. See Separate Article Early Days of Rock in Beijing in the Late 1980s factsanddetails.com

Describing his encounter with Cui around the same time, jazz musician and professor David Moser wrote in The Anthill: I was in Cui Jian’s apartment, giving him some jazz theory tips. A slight, soft-spoken young man, he would not have struck me as the iconoclastic godfather of Chinese rock. When I was at Peking University in the late 80s, his song “Nothing to My Name” played constantly on tinny dorm room cassette players.I knew Cui Jian played the trumpet, but I had no idea he was a jazz enthusiast. [Source: David Moser: The Anthill, January 2016]

“Are you thinking of branching out into jazz?” I asked him. “I can’t really play it yet,” he said, “but at least jazz is safe to perform here. It’s hard for me to get approval for concerts in Beijing, and even outside of the city I get banned all the time.” The politics of rock music were very much a topic of discussion. Chinese youth naturally felt a spiritual affinity with rock, and there were a few indigenous groups such as Tang Dynasty and Black Leopard that played for passionate fans across the country. Jazz was almost completely off the radar, but Cui Jian nevertheless saw potential for it.

““Rock is very direct, it’s good for shaking people up,” he said. “Jazz is subtler. It requires a longer time to take hold, but the effect on the spirit can be deeper. I believe it can also raise Chinese people’s political consciousness.” I reminded him that Miles Davis had once said, “Jazz is the big brother of revolution. Revolution follows it around.” He laughed. “Right. They say rock-and-roll is subversive, but from what I’ve read, jazz was really the music that brought down the Berlin Wall.”

Cui Jian and Tiananmen Square

Cui wrote, "I performed at Tiananmen in 1989, 15 days before the crackdown...The students needed me, and I needed them.” Cui's “Nothing to My Name”, a political song masked as a love song written in 1986, became the anthem of the Tiananmen Square demonstrations (See Lyrics Below). Insulting someone name's in China is like telling them to have sex with their mother. Commenting on the song, the Chinese general Wang Zhen once said, "What do you mean you have nothing to your name? You've got the Communist Party, haven't you?" Cui also angered authorities by performing another popular song, “A Piece of Red Cloth”, with a red blindfold covering his eyes and donning a PLA uniform and a red blindfold his album jackets. The strip of red fabric across his eyes to symbolized not wanting to see what was going on in China. See Below for the lyrics to that song too.

Cui Jan told The Times of London that before the tanks rolled in, Tiananmen Square was “like a party — a huge party.” He was 28 at the time and full of optimism and home for political change. “When we had a parry, the girls would be all around, screaming...we felt good...Enjoying the freedom. Thinking ‘This is my country. This is a chance for our minds to step up, internationally. [Source: Jamie Fullerton, The Times of London, August 2016]

“I was really clear about standing on the students’ side,” Cui told the BBC. “But not everyone liked what I did. Someone said, ‘Get out of the square. Don’t hurt the students’ health – they are very weak.’” He left Tiananmen by June 4, when troops from the 27th Army Group moved in and shot hundreds of civilians, clearing the square and abruptly ending the protest movement in a crackdown that so shook China that censors still forbid even the most oblique reference. But they could never stop people from listening to “Nothing to My Name.” The song is just too popular, even if not all of its listeners still remember its significance. Cui Jian said he made two visits to the Square during the protests there before playing a concert with a half dozen or so songs.

Cui Jian's Performance at Tiananmen Square

Max Fisher wrote in the Washington Post, “On May 20, 1989, Cui Jian walked onto the makeshift stage at Tiananmen Square. Thousands of protesters had held the square for weeks; their calls for political and economic reforms had inspired similar protests in dozens of Chinese cities, panicking the Communist Party leadership. The mood, though tense because of the troops surrounding the square, was still hopeful. No one knew that troops were to massacre hundreds of civilians 15 days later. Cui was already in famous in China, where his rock-and-roll attitude had shaken up a staid pop music scene and captured the imaginations of Chinese youth eager for something new and free-spirited. The crowds at Tiananmen were thrilled to receive him. “If you were there, it felt like a big party,” he later told the British newspaper the Independent. “There was no fear. It was nothing like it was shown on CNN and the BBC.” [Source: Max Fisher, Washington Post, June 14, 2013 -]

Max Fisher wrote in the Washington Post, “On May 20, 1989, Cui Jian walked onto the makeshift stage at Tiananmen Square. Thousands of protesters had held the square for weeks; their calls for political and economic reforms had inspired similar protests in dozens of Chinese cities, panicking the Communist Party leadership. The mood, though tense because of the troops surrounding the square, was still hopeful. No one knew that troops were to massacre hundreds of civilians 15 days later. Cui was already in famous in China, where his rock-and-roll attitude had shaken up a staid pop music scene and captured the imaginations of Chinese youth eager for something new and free-spirited. The crowds at Tiananmen were thrilled to receive him. “If you were there, it felt like a big party,” he later told the British newspaper the Independent. “There was no fear. It was nothing like it was shown on CNN and the BBC.” [Source: Max Fisher, Washington Post, June 14, 2013 -]

“The singer, ever a showman, wrapped a red blindfold over his eyes, a symbol of both the Communist Party and its attitude toward the problems that, according to the protesters, needed urgent reform. He later wrote in Time, “I covered my eyes with a red cloth to symbolize my feelings. The students were heroes. They needed me, and I needed them.” “Back then, people were used to hearing the old revolutionary songs and nothing else, so when they heard me singing about what I wanted as an individual they picked up on it,” he told the Independent, in explaining the success of “Nothing to My Name”. “When they sang the song, it was as if they were expressing what they felt.” At Tiananmen that day, Cui also sang “A Piece of Red Cloth.” which he called “a tune about alienation” in his Time article. It refers to a red blindfold, like that he wore in his performance, and though the lyrics are vague it certainly sounds like a reference to the Communist Party’s sternly authoritarian rule. Recall that the violent Cultural Revolution had ended in 1977, a decade before he wrote the song; the Party’s totalitarian era was over by 1989 but was not as distant then as it is today. -\

“Nothing to My Name,” quickly became an unofficial anthem of the protest movement and, later, a symbol of its tragic defeat. The song, which tells the story of a poor boy pleading with his girlfriend to accept his love though he has nothing, had made him famous three years earlier. Though Cui insists the song has no political meaning, it captured the changing – and politically charged – mood among China’s increasingly activist youth. It conveys disillusionment and dispossession but also a sense of hope: exactly the attitudes that electrified Tiananmen and the similar protests across China. -\

A 24-minute video clip of the concert shows Cui Jian playing four songs with his band: "Once Again From the Top", "Rock and Roll on the New Long March", "Like a Knife”, and “A Piece of Red Cloth'”. According to one description of the video: “There's a little bit of a tuning problem at the start, but then things get going with an energetic concert that has the listeners singing along to “Once Again From the Top” and “Rock and Roll on the New Long March” (both from the album Rock and Roll on the New Long March). After the second song, there's a bit of disagreement over whether they should be playing at all: one voice is concerned that about the state of the hunger strikers. The crowd disagrees, Cui says, “Most of the hunger strikers are over here,and I've got to be responsible to them.” Then the band launches into “Like a Knife” (which, like the fourth song, was included on the 1991 album Solution).”

“Before the next song, voices in the crowd reassure the band that they're OK with the boisterous music. Cui says, “If there's one student who doesn't want me to perform, I won't; it's about the safety of every person.....I came with about a 20 percent hope of performing, and 80 percent of just coming to see you all.” There are shouted requests for the fourth song, “A Piece of Red Cloth.” Prior to singing, Cui reads off the first verse, and people in the crowd call for everyone who has a piece of red cloth to put it on.”

Cui Jian After Tiananmen Square

After Tiananmen Square, Cui was forced to keep a low profile. His concerts were banned and he played instead at "parties," unofficial shows at hotels and restaurants. In 1990, he reemerged to help the government raise money for the 1990 Asian games. Afterwards his concerts and recordings were banned again because they were perceived threats of "dangerous disorder."

After Tiananmen Square, Cui was forced to keep a low profile. His concerts were banned and he played instead at "parties," unofficial shows at hotels and restaurants. In 1990, he reemerged to help the government raise money for the 1990 Asian games. Afterwards his concerts and recordings were banned again because they were perceived threats of "dangerous disorder."

In his 1990 New Long March tour, Cui Jan tied the red cloth around his eyes during the song “Piece of Red Cloth. The tour was shut down and Cui was unable to play a large show for the next ten years. After the blindfold incident he played outside China and did some small shows outside Beijing. In 2000, he was allowed to play large concerts in Beijing again. What was different then. “The ban was never written down. In China, big areas are grey.” In the 2000s, Cui Jian appeared in quite a few concerts yearly, including ones overseas. In 2009 he played in Madrid and Barcelona, .but played relatively few in China. [Source: Jamie Fullerton, The Times of London, August 2016]

Max Fisher wrote in the Washington Post, After the Tiananmen crackdown, Cui was still a big Chinese star. The authorities, perhaps not anticipating the anger around the June 1989 crackdown or the rebelliousness of rock musicians, allowed him to go on tour the next year. He performed in peasant clothes and wearing a red blindfold, an obvious nod to the protests and massacre. “Nothing to My Name” quickly became not just an anthem of the protests but their elegy, a way to remember the crackdown. A September 1990 show before 10,000 fans in Beijing’s Workers Stadium was the last large-scale concert that Chinese authorities allowed their country’s biggest rock star to make. [Source: Max Fisher, Washington Post, June 14, 2013 -]

Cui told Time that his songs are not political. "They are more personal. It's just truth, the modern truth. I think about our life in China...Chinese culture is like a river without an outlet. We need to unblock this river so that it can flow freely into the sea and mingle with the world.” In response to accusations that he is too negative, he says that he is simply expressing his feelings. "Rock 'n' roll us about equality,” Cui wrote in Time. ‘some Chinese are slaves to Western culture; other look East. I say f--- all of them and be yourself. That's what I like about rock 'n' roll. You can talk straight."

Cui Jian in the 2010s

Max Fisher wrote in the Washington Post, ““The man known as the grandfather of Chinese rock and roll is still playing in his home country, though rarely in venues larger than a bar or hotel lobby. A scholar of Chinese pop music, Jonathan Campbell, has said, “I can’t think of someone who has ever been more worthy than Cui Jian for induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.” Campbell explained, “He’s Woody Guthrie or Bruce Springsteen, whose songs made people suddenly realize that there are things going on about which we don’t know and ought to, and singing with the voice of the people not often represented in popular culture.” [Source: Max Fisher, Washington Post, June 14, 2013 -]

The Chinese culture scholar, Geremie Barmé wrote in his book “In The Red” : “The quality of [Cui Jian’s] later work and the corpus of his music probably would have condemned him to a short-lived career in a normal cultural market, but the unsteady politics of mainland repression lent him a long-term validity and the appeal reserved for a veteran campaigner.” In an interview with Vice , Cui lamented that Chinese youth today listen mostly to Western music. “China has such huge history and culture, and then [Chinese people] just want to leave that alone and listen to the Western music or culture,” he said. Like the Tiananmen crackdown itself, Cui’s anthems are both remembered and forgotten, too significant to ignore but increasingly repressed by a government eager to move on and youth who have other, more present concerns. -\

In 2014, China Central Television invited Cui to play on the annual variety show for the lunar new year. The TV gala is one the biggest television events of the year in China. Cui insisted on singing “Nothing to My Name”, the unofficial anthem of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, but the event's censors told him he would have to choose another song. After that Cui decided not to play the New Year show. “"It is not only our regret, but also the gala's," You You, Cui’s manager said. "Cui Jian has his fans all over the world, so his stage is far beyond the CCTV's gala." Many members of the Chinese public praised Cui for refusing to kowtow to China's censors. "You are still so proud,"Mongolian singer Daiqing Tana of the Beijing-based group Haya Band wrote on her microblog. "You are the backbone and gall of this land. Your music is the hope and despair of this country." [Source: Associated Press, January 18, 2014]

In September 2016, Cui Jan performed at Beijing’s Worker’s Stadium, where he one been barred. In 2015, he released his first album in ten years, “Frozen Light.” On dealing with censors, he said: “They want to show they have power. Every song I wrote was limited, but I think it’s a beautiful game. Several of my songs had a ‘ban it’ situation. OK, I’ll just write another one.” On China since Xi Jinping took power, Cui said: “The fear is always around. It’s like smoke. I have friends disappointed in me because I wouldn’t stand up and say something straight. In America, Chinese people talk about June 4 to see my reaction. But I said: ‘I have to go back to China tomorrow. It’s very dangerous to talk about June 4 right now.”

Lyrics for “Nothing to My Name” and “A Piece of Red Cloth”

Lyrics for “Nothing to My Name”:

“For a long time I kept on asking

When will you come with me

But all you do is laugh at me

For I have nothing to my name

I want to give you my dreams

To give you my liberty too

But all you do is laugh at me

For I having to my name.”

Oh! When will you go with me?

Oh! When will you go with me?

The ground beneath my feet is moving,

The water by my side is flowing,

but you always laugh at me, for having nothing.

Why does your laughter never end?

Why do I always have to chase you?

Could it be that in front of you

I forever have nothing to my name.

Oh! When will you go with me?

Oh! When will you go with me? I tell you

I’ve waited a long time, I give you my final request,

I want to take your hands, and then you’ll go with me.

This time your hands are trembling, this time your tears are flowing.

Could it be that you’re telling me, you love me with nothing to me name?

Oh! Now you will go with me! [Source: Max Fisher, Washington Post, June 14, 2013 -]

Lyrics for “A Piece of Red Cloth”:

“That day you used a piece of red cloth

To blindfold my eyes and cover the sky

You asked what I had seem

I said I saw happiness

The feeling really made me comfortable

Made me forget I had no place to live

You asked where I wanted to go

I said I want to follow your road.”

I couldn’t see you, and I couldn’t see the road

You grabbed both me hands and wouldn’t let go

You asked what I was thinking

I said I want to let you be my master

I have a feeling that you aren’t made of iron

But you seem to be as forceful as iron

I felt that you had blood on your body

Because your hands were so warm

This feeling really made me comfortable made me forget I had no place to live

You asked where I wanted to go I said I want to walk your road

I had a feeling this wasn’t a wilderness though I couldn’t see it was already dry and cracked

I felt that I wanted to drink some water but you used a kiss to block off my mouth

I don’t want to leave and I don’t want to cry

Because my body is already withered and dry I want to always accompany you this way

Because I know your suffering best

That day you used a piece of red cloth to blindfold my eyes and cover up the sky

You asked me what I could see I said I could see happiness. -\

Super Girl, Cui Jian and the Rolling Stones

In 2006, Cui performed with the Rolling Stones in Shanghai, singing Wild Horses with Mick Jagger. On his duet with Jagger, Cui said: “Every time people talk about this I feel guilty, I f**cked it up.” He had trouble with the words of “Wild Horses” “I asked Mick if I could sing it in Chinese. He said, ‘No, because most of the audience will be foreigners. I’d already spent a night translating it.”

In one edition of popular television show, “Super Girls”, a contestant named Huang Ying who normally sings mountain folk songs and “red” songs sang Cui Jian's “Nothing to My Name.” This was truly an unexpected choice. Beijing-based blogger Fang Kecheng wrote: “Maybe it was purely out of consideration for her voice and singing style, and she was given a song that would let her show off. I at least cannot believe that entertain-or-die Hunan TV would have had anything else in mind.” [Source: Fang Kecheng, a Beijing-based blogger]

‘so the curtain rose on a scene fraught with symbolism: Huang Ying, accustomed to performing things like “A 10th Blessing for the Red Army” entirely dispelled the significance of “Nothing to My Name”. Even though ELLE's Xiao Xue said, after the performance ended, “It's not easy for someone Huang Ying's age to understand the background, frame of mind, and mood this song had back then. A generation of people sang along with this song and danced to it.” But it seemed like this widely-detested woman's words fell on deaf ears: no one cared what she had to say, but everyone was just waiting for her to shut up and cast her vote for someone.”

“Twenty years ago, Cui Jian sang and turned red songs indecent ; twenty years later, a Super Girl turned an indecent song red . Twenty years ago, Cui Jian tried to use rock music to dispel things, destroy things, and also to build some things; twenty years later, Cui Jian has been dispelled by entertainment, rock music has been dispelled by entertainment, everything has been dispelled by entertainment. Twenty years ago, people sang and danced on the square, choked with emotions. Twenty years later, everyone waits in front of the television every Friday night in a frenzy to see which girl will win a singing competition.”

Image Sources: Fan, artist and Chinese rock websites and blogs, YouTube

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021