HEALTH IN TIBET

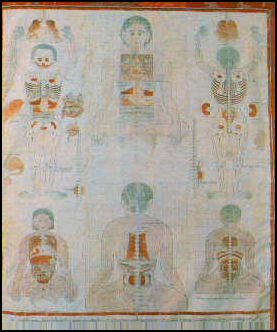

Health thangka of the human body Thanks to improvement in medical services over, average life expectancy in Tibet jumped from 35.5 in 1950 to 67 years in 2010 and 70.6 in 2019, according to a white paper issued by the Chinese government. Xinhua reported: Medical services have been greatly improved in Tibet. There are now 1,548 health facilities providing 19,787 beds in Tibet, with nearly 20,000 health and medical workers, said Qizhala, chairman of the Tibet regional government. China has been supporting the training of medical workers from Tibet in other parts of the country and encouraging health facilities in other areas to send personnel to train their counterparts in Tibet, Qizhala said. [Source: Xinhua, September 12, 2019]

Echinococcosis, a fatal parasitic tapeworm disease, and Kashin-Beck disease, a bone and joint disorder, as well as other endemic diseases related to high altitude, have been generally controlled or eradicated in Tibet, he said, noting that currently local health facilities in the region can provide treatment to 367 serious diseases. The population of the region has grown from 1.23 million in 1959 to 3.44 million in 2019.

Malnutrition was a serious problem and still is some parts of Tibet. One study in the 1990s showed that half the children in Tibet suffered from it and 60 percent of children were shorter than normal. People with serious health problems, handicaps and deformities are often ostracized. In some villages blind six-year-old children haven’t learned to walk because no one has taught them. Handicapped people are largely seen as being possessed by demons or paying for sins in past lives.

At high altitude, make sure you drink plenty of water. Tibet is so cold and arid that metal spoons sometimes stick to the lips and germs that cause many diseases can not survive. Lice, however, like to crawl all over the body to get warm.

Good Websites and Sources: Tibetan Medicine.com tibetanmedicine.com ; Resource Guide on Tibetan Medicine ; Paper on Tibetan Astrology and Medicine berzinarchives.com ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia

See Separate Articles: HEALTH AND DISEASES AT HIGH ALTITUDES factsanddetails.com; TRADITIONAL TIBETAN MEDICINE factsanddetails.com many articles TIBETAN LIFE factsanddetails.com TIBETAN PEOPLE factsanddetails.com FOOD IN TIBET Factsanddetails.com/China

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Essentials of Tibetan Traditional Medicine” (Illustrated) by Thinley Gyatso, Chris Hakim Amazon.com; “The Tibetan Book of Health: Sowa Rigpa, the Science of Healing” by Nida Chenagtsang and Professor Robert Thurman PhD Amazon.com; “Medicine and Memory in Tibet: Amchi Physicians in an Age of Reform” by Theresia Hofer Amazon.com “High Altitude: Human Adaptation to Hypoxia” by Erik R. Swenson and Peter Bärtsch Amazon.com; “Travel Health Experience in High Altitude Destination: Case Studies of Sagarmatha National Park (Nepal) and Tibet (China)” by Ghazali Musa Amazon.com; “Ward, Milledge and West’s High Altitude Medicine and Physiology” by Andrew M Luks, Philip N Ainslie, et al. Amazon.com

High Altitude Health in Tibet

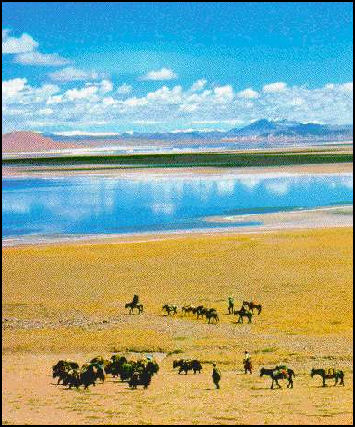

Tibetan nomads that live above 18,000 feet (5500 meter) often suffer discomfort when they descend to Lhasa at 11,550 feet. They have as much as 22 percent more oxygen-carrying hemoglobin in their blood than lowlanders and this extra hemoglobin makes it easier for the oxygen to reach their blood and organs.♠

Studies have shown that different groups deal with high-altitude, low oxygen environments in different ways. Sherpas breathe at a faster rate while Andeans have higher amounts of hemoglobin in their blood and have larger lungs which allow them to take in more air. Cynthia Beall, a scientist studying people living at high altitudes in Tibet, told National Geographic, "At this altitude — 5000 meters — all people have very low levels of oxygen saturation but in some they are not so low." She recently discovered that this trait is may be genetic.

Human beings are not very well adapted for high altitudes. Above 18,000 feet, cuts don't heal and women can not bear children. The air is so thin that they can not get enough oxygen into their blood to sustain a fetus growing within their womb. The dry air produces hacking coughs which are strong enough to produce cracked and separated ribs.

People weigh more at sea level than they do in higher levels. Not by much, but at measurable levels. Weight is a measurement of gravitation pull, in the this case between the earth and a person. The farther away you are from the bulk of the mass of one object the less gravitational pull. By one estimate a person who weights 150 pounds at seas level would weigh 149.92 at 10,000 feet.

Tibetans have unusually low blood hemoglobin levels, which allows them to thrive at high altitudes. When low-landers visit Tibet the low levels of oxygen in the bodies can cause altitude sickness. Jichuan Xing of the University of Utah Medical School said, “Presumably Tibetans have developed a regulation mechanism to control hemoglobin concentration to prevent these negative effects.”

See Separate Article LIFE AND HEALTH AT HIGH ALTITUDES factsanddetails.com

Adaption of Tibetans to High Altitudes

High altitude plains In a May 2010 paper published in Science a team headed by Jichuan Xing of the University of Utah Medical School found two genes — EGLN1 and PPARA in chromosomes 1 and 22 respectively — that appear to help Tibetans live comfortable at high altitudes. In a study the genes of 31 unrelated Tibetans were compared to the genes of 90 Chinese and Japanese. EGLN1 and PPARA turned up repeatedly in the Tibetans but not in the Chinese and Japanese. Xing wrote, “Their exact roles in high-latitude adaption is unclear. Both EGLN1 and PPARA...may cause a decrease of the hemoglobin concentration.”

Ann Gibbons wrote on sciencemag.org: “Researchers have long wondered how Tibetans live and work at altitudes above 4000 meters, where the limited supply of oxygen makes many people sick. Other high-altitude people, such as Andean highlanders, have adapted to such thin air by adding more oxygen-carrying hemoglobin to their blood. But Tibetans have adapted by having less hemoglobin in their blood; scientists think this trait helps them avoid serious problems, such as clots and strokes caused when the blood thickens with more hemoglobin-laden red blood cells. [Source:Ann Gibbons, sciencemag.org, July 2, 2014]

“Researchers discovered in 2010 that Tibetans have several genes that help them use smaller amounts of oxygen efficiently, allowing them to deliver enough of it to their limbs while exercising at high altitude. Most notable is a version of a gene called EPAS1, which regulates the body’s production of hemoglobin. They were surprised, however, by how rapidly the variant of EPAS1 spread—initially, they thought it spread in 3000 years through 40 percent of high-altitude Tibetans, which is the fastest genetic sweep ever observed in humans—and they wondered where it came from.”

Tibetans Inherited High-Altitude Gene from Ancient Human

In 2014, research was published that appeared to indicate that Tibetans inherited a gene that makes it easier to live at high altitudes from an ancient human group. Ann Gibbons wrote on sciencemag.org: “A “superathlete” gene that helps Tibetans breathe easy at high altitudes was inherited from people known as Denisovans, who went extinct soon after they mated with the ancestors of Europeans and Asians about 40,000 years ago. This is the first time a version of a gene acquired from interbreeding with another type of human has been shown to help modern humans adapt to their environment. [Source:Ann Gibbons, sciencemag.org, July 2, 2014]

“Now, an international team of researchers has sequenced the EPAS1 gene in 40 Tibetans and 40 Han Chinese. Both were once part of the same population that split into two groups sometime between 2750 to 5500 years ago. Population geneticist Rasmus Nielsen of the University of California, Berkeley, his postdoc Emilia Huerta-Sanchez, and their colleagues analyzed the DNA and found that the Tibetans and only two of the 40 Han Chinese had a distinctive segment of the EPAS1 gene in which five letters of the genetic code were identical. When they searched the most diverse catalog of genomes from people around the world in the 1000 Genomes Project, they could not find a single other living person who had the same code. Then, the team compared the gene variant with DNA sequences from archaic humans, including Neandertals and a Denisovan, whose genome was sequenced from the DNA in a girl’s finger bone from Denisova Cave in the Altai Mountains of Siberia. The Denisovan and Tibetan segments matched closely.

“The team also compared the full EPAS1 gene between populations around the world and confirmed that the Tibetans’ inherited the entire gene from Denisovans in the past 40,000 years or so—or from an even earlier ancestor that carried that DNA and passed it on to both Denisovans and modern humans. But they ruled out the second scenario—that the gene was inherited from the last ancestor that modern humans shared with Denisovans more than 400,000 years ago because such a large gene, or segment of DNA, would have accumulated mutations and broken up over that much time—and the Tibetans’ and Denisovans’ versions of the gene wouldn’t match as closely as they do today.

“But just how did the Tibetans inherit this gene from people who lived 40,000 years before them in Siberia and other parts of Asia? Using computer modeling, Nielsen and his team found the only plausible explanation was that the ancestors of Tibetans and Han Chinese got the gene by mating with Denisovans. The genome of this enigmatic people has revealed that they were more closely related to Neandertals than to modern humans and they once ranged across Asia, so they may have lived near the ancestors of Tibetans and Han Chinese. Other recent studies have shown that although Melanesians in Papua New Guinea have the highest levels of Denisovan DNA today (about 5 percent of their genome), some Han Chinese and mainland Asians retain a low level of Denisovan ancestry (about 0.2 percent to 2 percent), suggesting that much of their Denisovan ancestry has been wiped out or lost over time as their small populations were absorbed by much larger groups of modern humans.

Although most Han Chinese and other groups lost the Denisovans’ version of the EPAS1 gene because it wasn’t particularly beneficial, Tibetans who settled on the high-altitude Tibetan plateau retained it because it helped them adapt to life there, the team reports online today in Nature. The gene variant was favored by natural selection, so it spread rapidly to many Tibetans. A few Han Chinese—perhaps 1 percent to 2 percent—still carry the Denisovan version of the EPAS1 gene today because the interbreeding took place when the ancestors of Tibetans and Chinese were still part of one group some 40,000 years ago. But the gene was later lost in most Chinese, or the Han Chinese may have acquired it more recently from interbreeding with Tibetans, Nielsen says.

Either way, what is most interesting, Nielsen says, is that the results show that mating with other groups was an important source of beneficial genes in human evolution. “Modern humans didn’t wait for new mutations to adapt to a new environment,” he says. “They could pick up adaptive traits by interbreeding.” The discovery is the second case in which modern humans have acquired a trait from archaic humans, notes paleogeneticist Svante Pääbo of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, whose team discovered the Denisovan people. Earlier this year, another team showed that Mayans, in particular, have inherited a gene variant from Neandertals that increases the risk for diabetes.

See Separate Article ANCIENT AND PREHISTORIC TIBET AND EARLY TIBETAN HISTORY factsanddetails.com ; TIBETAN PEOPLE: HISTORY, POPULATION AND CHARACTERISTICS factsanddetails.com

Disease and Health Problems in Tibet

Health thangka

Even though Tibet is so cold and arid that many disease-causing agents can not survive, incidents of influenza, tuberculosis, and parasitic infections are high. The rate of respiratory disease is high. The smoke from yak-dung fires can be quite nasty and sting the eyes. Photographer Peter Menzel wrote: "The combination of smoke and flies was the worst I have seen anywhere. All the kids had diarrhea and runny noses, and most had some kind of skin infection." The family of 14 he stayed with included a father with a club foot, a hunchback son and dwarf-like daughter.

One study found that 67 percent of children in some Himalayan areas suffered from rickets, a disease caused by a Vitamin D deficiency.

In Tibet there were high incidents of Kashen-Beck disease, or Big Bone disease, an ailment that largely disappeared from rest of the world. By some estimates 9 percent of the population suffered from the disease. Sufferers have stunted growth, elbows with huge knots and hands, wrists and arms that are bent at strange angles. In the worst cases the long bones stop growing during childhood and sufferers look like dwarfs. Kashen-Beck disease is linked with poverty, poor diet, lack of minerals and bad water. It has also been linked with a fungus that grows in the soil in some places. The Chinese government helped to resettle people that lived in villages where the incidents of the disease were very high and the soil was contaminated with the fungus. Fungicides have been brought in to treat fields. Mineral supplements, iodine and selenium have been given to children

Tibetans suffer from unusually high incidents of eye disease. The high levels of ultraviolet rays found at high elevation takes its toll. After a lifetime of exposure to these rays many people develop cataracts (dense, foggy masses in the lenses) and go blind. Around 30,000 people in Tibet are blind as a result of cataracts. An additional 1,500 to 2,000 lose their sight every year because of them. Dri, Sanduk Ruit — a Sherpa from Nepal — came to Tibet in the late 1990s at the invitation of the Tibet Development Fund and has spent a great amount of time and energy performing operations to remove cataracts and training local doctors how to do the surgery.

Cataracts in Tibet have traditionally been treated with a 2,000-year-old procedure known as couching, in which the clouded part of the lens is removed but nothing is inserted to replace it, Although some sight may be restored vision is usually extremely blurry. The procedure used by Dr Ruit — replacing the clouded lens with a plastic lens — is simple and effective. The operation takes less than 30 minute, does not take great skill to perform and is relatively painless for the patients, who usually recover their sight within a couple days after the surgery.

Health Care in Tibet

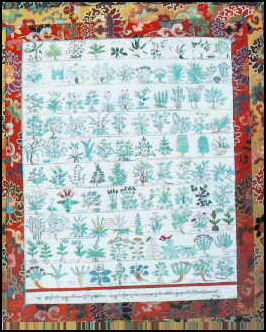

Tibetans have their own form of traditional medicine. A Tibetan physician named Yuthok Yonten Gonpo, compiled the Four Medical Classics of Tibetan Medicine, which include 70 colored wall charts made to assist diagnosis and the selection of drugs. Traditional doctors are called "amchi." Many of them are monks who received their training at monasteries. Yoji Kamata, a Japanese scholar who has studied Tibetan medicine told the Daily Yomiuri, "They don’t receive payment for helping others and they adhere to very high codes of conduct that follow Buddhist traditions.

Modern systems of health care were introduced by the Chinese in the 1950s. Health and health education improved greatly in the 1980s. Recent reforms have encouraged monks to teach hygiene and refer sick infants to clinics using Western medicine. Even when good, modern medical care is available people don’t always take advantage of it. A Swiss doctor working in Bhutan in the 1970s told National Geographic, "Only when they can no longer stand the pain do they come to me. Then it is often too late. I must say to them, 'Go home. It is not good to come to me only when they are ready to die.'"

Health Care in Tibet in the 1960s

According to the Chinese government: Tashi Tsering, the 61-year-old former director of the Nyalam county health bureau, has witnessed huge changes in Tibet's medical system. In 1966, Tashi was among the wave of the government's hastily trained medics known as barefoot doctors that provided basic medical care. He was sent to help rural farmers and herdsmen in Nyalam county in Tibet's Shigatse prefecture. [Source: Dachiog and Peng Yining Chinadaily.com.cn, Ministry of Culture, P.R.China, May 24, 2011]

After three months of training in the county hospital, he was dealing with a wide range of ailments, from diarrhea to appendicitis and even delivered babies, with little more than some anti-inflammatory pills and painkillers. "Once, a woman almost died giving birth to twins but I could do little to help her and her babies," he said. "When the second baby came out three days after the first one, it was dead."

Tashi said there was only one hospital in the county and there were no roads to some of the remote villages 160 kilometers away. According to an official report, before the peaceful liberation in 1951, there were no modern medical institutions in Tibet, except for three small, shabby government-run organizations that dispensed Tibetan medicine and a small number of private clinics that together had fewer than 100 medical workers.

BAREFOOT DOCTORS AND HEALTH CARE IN THE MAO ERA factsanddetails.com; Articles on HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Improved Health Care in Tibet

Tibet now has established a basic medical service across the whole autonomous region. In Nyalam county, for example, there are three hospitals and every village has at least two medics. A free medical service system, the first of its kind nationwide, has also been founded. According to the Chinese government: Tsering Norbu, a 33-year-old Shigatse resident, said 85 percent of his medical fees for treatment following a car accident were reimbursed by the government. Residents can borrow 5,000 yuan ($770) from the local health bureau and get the money reimbursed by the government if they cannot repay it," Tsering said. [Source: Dachiog and Peng Yining Chinadaily.com.cn, Ministry of Culture, P.R.China, May 24, 2011]

Hospitals in Lhasa in the 2000s have departments of medicine, surgery, gynecology, obstetrics, oncology, gastrointestinal medicine and pediatrics that catered to outpatients. In addition, they had more than 20 special outpatient departments, including ones for disease prevention and health protection, oral hygiene, ophthalmology, external Tibetan therapeutic medicine, radiology, ultrasound and endoscopy. Hospitals have adopted the method of combining Western and Tibetan medicine to treat diseases, thereby enriching and developing Tibetan medical therapies and theories.

In 1995, Tashi organized training for grassroots medics with the support of local officials. They have trained more than 370 Tibetans and 60 percent of them now work as full-time medical staff in Shigatse. Tashi said medical workers also educate residents on medical knowledge. "In the old Tibet, few people knew about and accepted vaccines. Being afraid of needles and injections, women ran away carrying their babies when I went to their tents to persuade them," said Tashi. "The tradition of giving birth at home causes many infections, dead babies and dead mothers."

Dondrup Drolma, a 26-year-old Tibetan woman, said she was born in a cattle-shed. "Sometimes, people keep the labor a secret in case it will bring bad luck to the baby," she said. Tashi said in order to encourage women to give birth in hospitals, the government gives 100 to 200 yuan in subsidies to every patient and covers their transport expenses.

According to official reports, the maternal mortality rate dropped from 50,000 per million in 1959 to 1,748 per million and infant mortality fell from 43 percent to 2.07 percent. Tashi attributes the improvement to the government's constant investment in medical development. But he said Tibet still needs more well-trained medical workers. "Surgeons are still needed in many regions in Tibet," he said. "More local Tibetan medics, most of whom are taught for several months in local hospitals, should be sent to medical school for at least two years of training."

The General Hospital of the Tibet Military Command, specialized in research on acute mountain sickness (AMS). It set up the region's first postdoctoral research station on May 2011. [Source: (Xinhua, May 5, 2011]

Image Sources: Purdue University except Everest by Luca Galuzzi

Text Sources: 1) “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China”, edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K.Hall & Company, 1994); 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China ethnic-china.com *\; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2022