TIBETAN UPRISING IN 2008

In mid March 2008, a major Tibetan uprising erupted in Lhasa and spread to other Tibetan regions of China. Chinese authorities said 22 people were killed, most of them Chinese killed by "separatist followers of the Dalai Lama.” More than 600 people were injured. The violence was more serious than the unrest in 1989, which was primarily confined to Lhasa, and was arguably the worst outbreak of violence in China since the Tiananmen Square crackdown in 1989.

The Tibet-in-exile government says 220 monks, nuns and other Tibetans died, most of them killed by Chinese soldiers and police suppressing riots and demonstrations. and 7,000 were detained and more than 1,000 were injured in the ensuing crackdown. Many Tibetans believe that hundreds if not thousands were killed. Dozens of photographs of bloodied Tibetan corpses were displayed in Dharmasala. It is widely believed though that more people were killed in the riots in Urumqi, Xinjiang in 2009 than in Tibet.

A Tibetan resident told Reuters, “Nobody believes the official death toll, There was too much violence, The things I saw, the burnt out shops, cars and buses, Many more people must have died.”The respected Tibetan poet and blogger Woeser, using accounts of those she said she trusts, estimates as many as 300 people may have died at the hands of public security forces. It’s impossible to know the exact number because the bodies are always immediately cremated, she said.

During the riots in Lhasa on March 14, hundreds of mostly young Tibetans roamed the streets in mobs and gangs, throwing rocks and paving stones at police, attacking Chinese on bicycles and in taxis and vandalizing and setting fire to Chinese stores. The Bank of China was attacked and quickly turned into a smoldering ruin. Video, camera and cell phone images caught angry Tibetans smashing Chinese shops and setting fire to looted materials in streets.

According to the Chinese government 19 people were killed and 383 people were injured, 57 of them seriously, in the riots on March 14 in Lhasa. The dead included 18 civilians and one policeman. Almost all the victims, according to government acounts, were Chinese, many of whom had been burned, bludgeoned on hacked to death by rioters. The government also said arsonists and protesters set fire to 908 shops 84 vehicles, seven schools and 120 homes and looted 1,367 shops, causing an economic loss of about $47 million.

Muslim shopkeepers and their families were badly hurt and some were killed when fires set in their shops spread to upstairs apartments. The Chinese media reported that Tibetan protesters sliced off the ear of a Chinese woman. In March 2009, the Tibetan government in exile in Dharamsala, India, released a seven-minute video that purports to show Chinese police officers brutally beating Tibetans during the 2008 riots. There has been no independent confirmation that the footage is authentic.

Tibetans directed their anger first at Chinese and then at Muslim Huis. An American who witnessed the events told the New York Times, “This wasn’t organized, but it was very clear that they wanted the Chinese out.” The unrest came as a shock to the authorities, who thought decades of generous investment in Tibet had gone a long way to mollify lingering resentment toward Beijing.

See Separate Articles: TIBET IN THE 1980s, 1990s AND 2000s factsanddetails.com ; AFTER THE TIBETAN UPRISING IN 2008 factsanddetails.com ; PROTESTS AND VIOLENCE IN TIBET AFTER THE 2008 RIOTS factsanddetails.com ; SELF-IMMOLATIONS IN TIBET factsanddetails.com ;

Good Websites and Sources: Eyewitness Accounts in Christian Science Monitor csmonitor.com ; Photos uprisingarchive.org; Central Tibetan Administration (Tibetan government in Exile) www.tibet.com ; Chinese Government Tibet website eng.tibet.cn/; Wikipedia article on Tibet Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on Tibetan History Wikipedia ; Tibetan News site phayul.com ; Snow Lion Publications (books on Tibet) snowlionpub.com ; Tibet Activist Groups: Free Tibet freetibet.org ; Tibetan Centre for Human Rights and Democracy tchrd.org ; Tibetan Studies and Tibet Research: Tibetan Resources on The Web (Columbia University C.V. Starr East Asian Library ) columbia.edu ; Tibetan and Himalayan Libray thlib.org Digital Himalaya ; digitalhimalaya.com ; Center for Research of Tibet case.edu ; Tibetan Studies resources blog tibetan-studies-resources.blogspot.com ; Book: "Tibetan Civilization" by Rolf Alfred Stein.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Tibet's Last Stand?: The Tibetan Uprising of 2008 and China's Response” by Warren W. Smith Jr. Amazon.com; ““I Saw It with My Own Eyes”: Abuses by Chinese Security Forces in Tibet, 2008-2010" by Human Rights Watch Amazon.com; “Return to Tibet: Tibet After the Chinese Occupation” by Heinrich Harrer Amazon.com; “The Struggle for Tibet” by Wang Lixiong and Tsering Shakya Amazon.com; “Tibet: A History Between Dream and Nation-State” by Paul Christiaan Klieger Amazon.com; “Tibet on Fire: Self-Immolations Against Chinese Rule” by Tsering Woeser and Kevin Carrico Amazon.com; General History: “Tibet: A History” by Sam van Schaik Amazon.com; “A Historical Atlas of Tibet” by Karl E. Ryavec Amazon.com; “Histories of Tibet” by Kurtis R. Schaeffer , William A. McGrath, Amazon.com; “Himalaya: A Human History” by Ed Douglas, James Cameron Stewart, et al. Amazon.com; “Tibet & Its History” by Hugh Richardson (1989) Amazon.com; "Tibetan Civilization" by Rolf Alfred Stein Amazon.com; “The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama” by Thomas Laird Amazon.com

Events Before Tibetan Rioting on March 14th

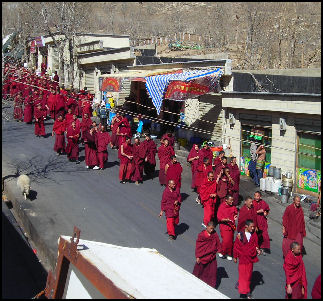

monks outside Drepung

The trouble began March 10 when hundreds of monks staged a protest at Drepung monastery, located about eight kilometers outside Lhasa, to commemorate the anniversary of the March 10 revolt in 1959. Monks that marched towards Lhasa were prevented by police from entering the city. Protestors that shouted Tibetan independence slogans and unfurled a homemade Tibetan flag were quickly whisked away by police. At least 15 people were detained. On the same day students and monks staged a second protest in Lhasa, making a circle around Barkhor Square in front of Jokhang Temple, and joining hands, The square filled with police. Foreign witnesses said six or seven demonstrators were taken away by police.

Everyone expected protests around this time to mark the Tibetan revolt in 1959 and people expected them to be bigger than usual with world attention focused on China with the Beijing Olympics only months away. Rumors began circulating of killings, beatings and detention of Buddhist monks by security forces in Lhasa. A novelist who was traveling in Lhasa at the time told the Washington Post, “A lot of Tibetans...were distraught by the arrests of the monks.”

A larger protest took place on March 11, this time by monks at Sera monastery, also outside Lhasa. At first, nine monks emerged from the monastery and were immediately taken away by police. Later several hundred monks emerged, demanding the release of the nine. Tear gas was fired to disperse the crowd. Dozens of monks are believed to have been arrested..

A foreign tourist who witnessed a clash between monks and police at Sera monastery told the BBC, “They were grabbing monks, kicking and beating them. One monk was kicked in the stomach right in front of us and then beaten on the ground."

Things were fairly quiet on March 12 and 13. Access to Lhasa’s three monasteries was blocked by police. Monks at Sera monastery went on a hunger strike. A Tibetan poet reported on his blog that two monks at Sera monastery slit their wrists in suicide attempts.

There seemed to be a coordinated effort among Tibetans all over the world to stage protests to mark the March 10, 1959 revolt. At the same time events were unfolding in Lhasa, hundreds or Tibetan exiles in India began a protest march from India to Tibet, defying orders from the Indian government and the Dalai Lama The Dalai Lama said was against the march because it would alienate Indians — who served as hosts for Tibetan exiles — and invited a confrontation with the Chinese at the Chinese border that could turn deadly. The march was organized by the Tibetan Youth Congress and other pro-Tibetan groups. After the first march was stopped by Indian authorities days after it began, a second was started.

Beginning of the Rioting in Tibet on March 14th

Bharkor

In the morning of March 14, trucks filled with riot police began driving around Potala Palace and taking up positions at Jokhang Temple. At Rampoche Temple, a small shrine up a pedestrian street from Lhasa’s main square, monks began a march around noon and were immediately met by police. The confrontation took place in the old Tibetan quarter of Lhasa and quickly drew a crowd that didn’t need much provocation to go after the police. Rumors had been spreading that monks had been shot at Jokhang temple and beaten at another temple.

Soon a mob began pelting police with rocks and paving stones. Witnesses said the police were outfit with riot gear, batons and shields but no guns, and were quickly overwhelmed. One witness told the New York Times, “Almost immediately they were rushed by a massive group of Tibetans. Trucks brought in reinforcements but they too were pelted with stones. Most of the stone throwing was done by a couple dozen Tibetans in their teens and 20s, cheered on by several hundred older Tibetans. Some of the paving stones were hurled with such ferocity they cracked the police shields. The police fled and sought refuge in an alley. With the police gone the mob began venting its frustration on Chinese passersby and then Chinese-owned shops and businesses.”.

Two Swiss tourists told the Washington Post they saw a crowds of more than 100 people, including several monks, in a square. The crowds pelted nearby fast-food restaurants with rocks, and broke in and threw boxes of food and supplies in the square and set them on fire. Firefighters arrived to put out the fires but fled when Tibetans began attacking their truck.

Rioting Turns Ugly in Lhasa on March 14th

With the police gone, gangs and mobs, some of them behaving like wild animals, were allowed to run free. A Canadian tourist told the Los Angeles Times, “At first it was sort of a game...You throw the rocks and you run away. But then the scene turned incredibly ugly.”

A Canadian backpacker told the Washington Post he joined a mob of 100 or so, screaming “Free Tibet!,” that chased riot police down an alley. The mob threw rocks at the police, who turned and ran, some leaving their shields behind. Afterwards the Tibetans congratulated one another and then began gathering rocks and pulling out knives. “There was no crowd to be part of,” the backpacker said, “It looked like they were turning on everyone. It wasn’t about Tibetan freedom anymore.”

A Chinese man told the Washington Post he heard a “strange, high-pitched sound” and turned to see a gang of 30 or 40 young women with masks over their mouths. “They were attacking even more fiercely than the boys.”

One Chinese man told the Washington Post that from the roof of his hotel he saw a Tibetan man wielding two knives jump of a police SUV, shouting and slashing. Others approached and turned the vehicle on its side and set it on fire.

Witnesses saw a teenage boy pulled from a bicycle and bludgeoned on the head and was rescued by a tall foreign man. A Swiss tourist told the Times of London, “They were kicking him in the ribs and he was bleeding from the face. But then a white man walked up....helped him up from the ground. There was a crowd of Tibetans holding a stone. He held the Chinese man close, waved his hand at the crowd and they let him lead the man to safety.”

Rioters first attacked Chinese shops and businesses and then attacked businesses in the Muslim Hui quarter. There mobs attacked a mosque but were unable to get inside. Some groups moved on and punched holes through metal shop gates and poured gasoline in the shops and set them on fire. I wasn't until evening that Chinese authorities dared to set foot in central Lhasa.

Police During the Rioting in Tibet on March 14th

When the protests turned violent the police fell back rather than confront the rioters, An American woman in Lhasa told the New York Times, “The whole day I didn’t see a single police officer or soldier. The Tibetans were just running free.” James Miles of the Economist, the only Western reporter on the scene with permission to be in Lhasa, told the Washington Post and the New York Times, “That’s what astonished me. There was a complete absence of security or of any uniformed presence on the street....I was looking around expecting an immediate, rapid response. But nothing happened.”

Miles wrote in the Economist: “A handful of riot police with shields and helmets (but no guns visible) patrolled in front of the Jokhang as the riots continued around them, while others stood in lines at the perimeter of the riot-torn area. But for many hours they made no attempt to intervene. After nightfall fire engines, supported by two armored personnel carriers, moved down the streets putting out the blazes. But the police carrying automatic rifles did not attempt to deploy on the streets, the occasional bang was heard, but it was difficult to tell whether it was shooting or explosions in the fire.”

There were reports of the police being more intent on videotaping the protesters — with the cameras focused on faces, presumably so the police could track down troublemakers later — than quelling the riots. One man told the New York Times, “They were just watching. They tried to make some videos and use their camera to take some photos.” Similar tactics were used months before in Myanmar.

Murray Scott Tanner, an expert on Chinese security forces, told the New York Times, “I really am surprised at the speed which these things got out of control. This place, this time, should not have surprised them. This is one of the key cities in the country that they have tried to keep a lid on for two decades.”

Looting and Burning During the Tibetan Riots on March 14th

Abarrel of gasoline was uncorked and poured into the doorway of a shop and ignited. Cars were upended and set on fire with burning Chinese flags on top of them. Fires blazed out of control in several locations, The rioters seemed more interested in destroying than looting. Mobs and gangs kicked down doors and pulled down shudders protecting shops and burned what they pulled out. The offices of the state-run Tibet Daily and Xinhua news agency were targeted. A Chinese man said he saw a man with a megaphone assisted by a pointing woman that appeared to be directing the mob where to attack.

James Miles of the Economist wrote: “I saw crowds hurling chunks of concrete at the numerous small shops run by ethnic Chinese lining the streets of the city’s old Tibetan quarter. They threw them too at those Chinese caught on the streets — a boy on a bicycle, taxis (whose drivers are often Chinese) and even a bus. Most Chinese fled the area as quickly as they could, leaving their shops shuttered.”

“The mobs ranged from small groups of youths (some armed with traditional Tibetan swords) to crowds of many dozens, including women and children, rampaging through the narrow alleys of the Tibetan quarter. They battered the shutters of shops, broke in, and seized whatever the could, from hunks of meat to gas canisters and clothing. Some goods they carried away — little children could be seen looting a toy store — but most they heaped in the streets and set alight.”

“Within a couple of hours, fires were blazing in the streets across much of the city. Some buildings caught fire too. A pall of smoke blanketed Lhasa, obscuring the ancient Potala...which covers a hillside overlooking the city...Some of the demonstrators shouted slogans like “Long Live Tibet” and “Long Live the Dalai Lama.” One group trampled on a Chinese flag in the middle of the main road.”

“Residents had mixed feelings about the violence...Some celebrated by throwing rolls of lavatory paper over wires across the streets, filling them with streamers intended to resemble traditional Tibetan scarves. Others appeared aghast at the violence. I spoke to a monk in the backroom of a monastery, a teenage boy rushed in prostrated himself before him. He was a member of the China’s ethnic Han majority, terrified of the mobs outside. The monk helped him to hide.”

Deaths During the Rioting in Tibet on March 14th

Among the 22 reported dead in Lhasa were a policeman beaten by a mob and shopkeepers burned in the fires. The most noteworthy deaths were an eight- month old baby and five employees of a clothing shop that had sought refuge on the second floor of their shop and were burned alive when they shop was set on fire. The eight-month old baby died with his mother and father and two others when Tibetans set fire to a Han-Chinese-owned motorcycle shop with two containers full of gasoline. Most of the victims according to government tallies were Han Chinese.

Four of the women in the clothing shop were Han Chinese. One followed her fiancé to Lhasa. Another sent most of her earnings home to support 13 relatives. Several sent text messages to relatives just minutes before they died. The fifth was a 21-year-old Tibetan woman who used her earnings to support her family. Her family was as angry as those of the Han victims about what happened.

The women were working when Tibetans went on a rampage in the old Tibetan quarter where their shop was located. The Tibetan woman text-messaged her relatives: “Don’t go outside, We are hiding in the store.” One of the Chinese women wrote in another message: “Mom, don’t go outside. Be careful. Some are killing people.” Another wrote her father at 3:32pm: “I am safe at the store.” After that there were no more messages. [Source: David Barboza, New York Times]

A Swiss tourist told the Washington Post, he saw an old Chinese man pulled off his bicycle and thrown to the ground, where rioters smashed his head with a large rock. ‘some older Tibetans went to try to stop them,” the tourist said, “but others were howling like wolves. That's how they supported. Everything that looked Chinese was attacked and beaten up.” Witnesses also saw a Chinese man pulled from a motorcycle and bludgeoned “most likely to death — with paving stones. A Canadian backpacker said, “They got him in the head with a large piece of sidewalk. He was down on the ground and he was not moving.”

On the morning after the riot a Chinese man told the Washington Post he saw police with white gloves carry a body bag out of a smoldering building, “We didn’t realize that...people could be killed," he said. “Why did this happen, even the Tibetans ask?” The Chinese government said that it gave families of the dead $28,500. The government also promised to pay the medical bills of those injured and help owners of damaged shops rebuild.

There were reports of Tibetans being shot in front of Jokhang Temple during the evening and night of March 14, with families coming to collect the bodies late in the night, offering prayers and leaving white scarves, One rioter told Radio Free Asia, “Many of those killed were young Tibetans, both boys and girls. Those who are dead sacrificed their lives for 6 million Tibetans. My disappointment is that we were not armed.” There were also reports of 26 Tibetans being killed outside Drapchi prison. These claims could not be independently confirmed.

Reasons for the of Rioting in Tibet on March 14th

police under attack

The riots seem to have been a spontaneous reaction to increased oppression in Tibet. One Tibetan exile in India told the Washington Post, “Our blood is very hot right now, We have waited so many years for China to change its mind. Six rounds of peaceful talks, and we have nothing to show, But now, we are in no mood to spare China.”

Abraham Lustgarten, author of a book on the Tibetan railroad, wrote in the Washington Post: “The targets of destruction and violence were not random. The cars topped....were expensive Toyota Land Cruisers and slick Hondas and Audis...The shops burning were Chinese-owned stalls and businesses.”

Miles wrote in the Economist: “The rioting seemed primarily an eruption of ethnic hatred. Immigrants have been flocking into Lhasa in recent years from the rest of China and run many of its shops, small businesses and tourist facilities....There is a great deal of resentment over sharp increases in the prices of food and consumer goods from the rest of China. Many residents are suspicious of the new train service, which they felt might encourage immigration.”

The violence was fueled by rumors of killings, beatings and detention of Buddhist monks by security forces in Lhasa. A spokesman for the Dalai Lama said, “It started off with just one or two incidents. Because of technology, because of word of mouth, word spread quickly. This was very spontaneous.” Some believe the whole thing was set up by the Chinese, swearing that some of the monks were Chinese in monk robes.

Afterwards some Tibetans said they were proud they were able to finally stand up the Chinese. Others were ashamed by the violence. Regardless of their stand on the riots they complained of discrimination and unequal pay and had heard rumors that monks had been arrested, beaten and killed.

Blame for the Tibetan Riots

Tibetan with a stick Beijing blamed the riots not on its policies in Tibet but on efforts by separatist and outsiders to break up the motherland. One official said, “There’s no such thing as an ethnic problem in Tibet, Han and Tibetans live in harmony and peace.”

Beijing blamed Western governments for encouraging Tibetans to fight against the Chinese and plotting against Beijing. One statement blamed the “Tibet issue” on “Western anti-China forces” attempting to “restrain, split and demonize China.”

Shortly after the riots, the Chinese government claimed it had captured the head of an underground network with links to the Dalai Lama that was planning to organize suicide squads to carry out attacks with the aim of forcing China to give up control of Tibet. The suspect who was captured reportedly said he was acting on the Dalai Lama’s orders. A spokesman for the Dalai Lama said the charges were ridiculous and the Dalai Lama remained committed to non-violence. The news came not long after demands were made on the government to back up its claim that the Dalai Lama orchestrated the riots.

Crackdown After the Tibetan Uprising

March 15th was mostly quiet in Lhasa. On the night after the riots PLA armed police created a perimeter encircling the riot area. Armored vehicles and riot police armed with high-powered rifles and automatic weapons took up positions outside some places. Some people in Lhasa said they heard the sounds of gunshots and tear gas projectiles as police slowly took control of the city.

People were ordered to stay inside. Messages broadcast over loudspeakers warned residents to “discern between enemies and friends, maintain order.” Rioters wanted by police were told if they turned themselves they might be treated leniently. In some places military checkpoints — manned by young soldiers with bayonets fixed to their rifles — were set up every 10 to 15 meters. A Swiss tourist told the Times of London, “They were really young and nervous. They always had their finger on the trigger — that’s what made us really nervous.”

More police and paramilitary troops poured into Lhasa. By March 16, paramilitary police were going from house to house and dragging away suspects. One foreigner told the New York Times he saw Tibetan men beat up so badly police sprinkled white powder on the ground to cover the blood."

After the initial riot more than 1,000 Tibetans were arrested and all monasteries were closed. The Lhasa public security bureau issued a most-wanted list of 53 suspects, whose images were posted on websites and television. Monks were subjected to “patriotic education.”

Zhang Qingli, the top Communist party official in Tibet and a protégée of Chinese President Hu Jintao, was not in Lhasa. He was at the Party Congress in Beijing. As the riots were getting underway he was heading a two-hour online discussion on China’s Supreme Court.

Coverage of the Tibetan Uprising

The first reaction by the Chinese government was a news blackout followed by a carefully choreographed campaign to make the Tibetans look bad. As the riots and crackdowns were occurring Chinese television was dominated by reports of the National People’s Congress, which was took place at the same time, with the agenda being followed on cue as of nothing was happening in Tibet.

The news in Tibet was different. Describing television coverage in Tibet on the night of the main riots, Miles wrote in The Economist: “During the evening, Lhasa television broadcast over and over again, alternately in Tibetan and Chinese, a government statement accusing the “Dalai Lama clique” of being behind the violence by a small number” of rioters. It called on city residents to support the authorities’ efforts to restore control.”

After the initial riots were over Chinese television began showing clips of rioters looting Chinese shops, setting fires to looted goods and attacking Chinese. Monks or men in monks robes were shown kicking in store fronts and throwing rocks at riot police. Injured Han Chinese were shown recovering in hospitals. Messages in the media repeated over and over again that the riots were orchestrated by the “Dalai Lama clique.” No mention was made of injured of killed Tibetans or the underlying grievances that sparked the uprising.

The plan it seemed was to stir up nationalist sentiments and drum up support for a government crackdown in Tibet. The coverage by the Chinese government achieved its result. While the uprising elicited sympathy for Tibetans among the global audience, images of looting monks and mobs attacking innocent Chinese, evoked anger towards Tibetans by ordinary Chinese, the audience that matters most to the Chinese government. Doing something that it had rarely done before, the Chinese government portrayed Chinese as victims, in this case of Tibetan aggression. One analyst told the Los Angeles Times, “In this crisis, their strategy has been pretty effective. They’ve been able to portray it as “we Chinese” versus “they Tibetans” and seen public opinion go their way.”

Foreign Coverage of the Tibetan Uprising

At the time of the riots only one authorized foreign reporter was in Tibet: James Miles of the Economist. Many images that made their way out came via Hong Kong reporters who made into to Lhasa with their Chinese passports. The Great Firewall was put into overdrive. Youtube, Google, Yahoo! and the New York Times website were all blocked in China. Searches in China for “Tibet,” Lhasa,” “demonstrations” and “March 14" turned up nothing. Images in the BBC and CNN television were blacked out. A lot information — including cell phone photographs and amateur videos and reports from inside the trouble spots was disseminated on the Internet via blogs and chat lines.

After the CNN cropping case appeared other examples were found in releases from the Times of London, Fox News, German television and French radio, leading some nationalists to argue an organized conspiracy against China was taking place in the Western media

About 10 days after the March 14 riot, a group of Chinese and foreign journalists — including a reporter from USA Today but no one from the New York Times or the Washington Post — was taken on a carefully-choreographed, three-day tour of Lhasa. They were shown destruction caused during the riots and met with rioters who confessed they had done wrong. A group of monks crashed an official press tour of Jokhang Temple in Lhasa, accusing Chinese authorities of lying about the clashes in Lhasa. In an another media tour in April, monks interrupted a speech by a top Chinese official in Tibet, saying, “We are not asking for independence, we are just asking for human rights , We have no human rights now.” They also said another important things for all Tibet is that the Dalai Lama be allowed to return to Tibet.

Chinese who saw foreign media reports were outraged that Chinese not Tibetans were made out to be villains.. One Chinese person wrote on an Internet chat line. “I use to think the Western media were fair. But how could they turn a blind eye to the killing and arson by rioters?” Another, a student at the University of Chicago, wrote in an e-mail, “Imagine everyday you open the news and it’s all saying biased words towards your motherland: crackdown, killing, burning....I don’t understand, they struggle for press freedom and fairness, but why would they lose their conscience now?”

A website called anti-cnn.com pointed out that images of police scuffling with protestors in Nepal shown on CNN had been identified as taking place in China and showed how an image of a Chinese military vehicles shown on CNN had been cropped so as not to show Tibetan rioters pelting the vehicle with rocks.

Many countries — including the United States — called for Chinese leaders to open a substantiative dialogue with the Dalai Lama and allow more journalists and diplomats into trouble spots in Tibet so that what was going on there could be more accurately ascertained.

Protests Spread Outside of the Lhasa Area

protest in Amdo

At least 150 incidents of unrest were reportedl in other areas, including remote parts of neighboring provinces like Qinghai. As of late March protests has been reported in 49 locations, including a half dozen or so in the Lhasa area. Most of the protests took place in the western part of the area populated by Tibetans: in western Tibet Autonomous Region, western Qinghai, southern Gansu, eastern Sichuan and northwest Yunnan. Most of what went there is unknown because no one from the outside was allowed in to cover it.

On March 15, a day after the riots in Lhasa, more than 1,000 Tibetans marched against the Chinese at Labrang Monastery in Xiahe, 750 miles northeast of Lhasa. There were reports of many injuries after Tibetans threw rocks at police and police responded with tear gas.

On March 16, Tibetans in Aba County in northern Sichuan attacked a police station and set fire to a market, police cars and fire trucks. A policeman was reportedly killed in the conformation. Police reportedly fired into a crowd, killing at least eight. Later the Chinese government admitted shooting four protesters in Sichuan, but said the police fired in self defense and only wounded their attackers. Pro-Tibetan groups released photographs of bloody dead bodies on their website which they said were of victims of the Aba riots.

Nomads, farmers, and students participated in the protests. Many carried forbidden Tibetan flags. There were about 20 incidents in which Tibetan offices were burned down.

Chengdu, the gateway to western Sichuan and Tibet, became a clearing house for information from Tibetan areas in China. Many members of Chengdu’s Tibetan community were in contact with family members in areas where trouble had occurred. Roads westward from Chengdu were closed at all traffic except military convoys.

There were reports of clashes between protesters and police in Ganze Tibetan Autonomous Region after police tried to halt a march by 2,000 monks and nuns. A week after the Lhasa riots a policeman and a monk were killed and another monk critically injured when a peaceful march turned violent after protestors were confronted by police. Chinese news sources said the protestors attacked the police with knives and stones. Tibetan sources said the police opened fire on the demonstrators.

One monk in Chengdu told the New York Times that his home village in Luhuo County had been littered with fliers calling on Tibetans to protest. A second monk said that his monastery in Aba County had been surrounded by Chinese security forces. After calling relatives with his cell phone a third monk said police had killed one Tibetan protester and injured nine others in Serta Country.

Two monks committed suicide in Aba County in late March. One left a note that said, “I do not want to live under Chinese oppression even for a minute.” The other, a 73-year-old senior monk, told followers, he couldn’t “beat oppression anymore.” At Longwu Temple in Qinghai, two young monks beat themselves bloody with stones and another slashed himself with a knife.

In April 2008, according to Free Tibet Campaign, police opened fire on hundreds of protesters Donggu town in Ganze, killing eight people. Radio Free Asia said up to 15 people were killed. Government sources said one government official was seriously injured in what it called a riot. The protestors, which included monks and lay people, had marched on local government offices demanding the release of two monks, detained for possessing pictures of the Dalai Lama.

In late April, Beijing reported the shooting death of a Tibetan by a policeman in northwestern China, the first time the government admitted a Tibetan was killed by government security forces, and the shooting death of a Chinese policeman by Tibetans that occurred while the policeman was trying to arrest a Tibetan leader.

Tibetan students at universities across China held candlelight vigils for victims

Crackdowns Outside of the Lhasa Area

Areas with large Tibetan populations, especially places where there had been unrest, came under tight military control. Roadblocks were set up. House-to-house searches were conducted to ferret out troublemakers.

“Patriotic campaigns” at monasteries were stepped up. Three thousands paramilitary troops searched the monastery in Ganze and detained monks for possessing pictures of the Dalai Lama. At Kumbum Monastery in Xining in Qinghai Province, soldiers took up positions inside and outside the monastery.

dead Tibetans in Ngaba

According to government reports 289 people had turned themselves into police in Gannan Tibetan Autonomous area of southwestern Gansu Province and 381 people were arrested in Aba county in northern Sichuan. In town known in Tibetan as Rebkong, and in Chinese as Tongren, local monks protested in front of government offices. An eyewitness quoted in a report by Human Rights Watch described a scene of ‘soldiers and police beating the crowd with electric batons.” A man in his sixties reportedly began shouting, “May His Holiness the Dalai Lama live for ten thousand years!” and “Tibet is independent!” According to the witness, “Five or six soldiers threw him to the ground and beat him so severely that he seemed close to death.”

There was an uprising at Geerdang monastery on March 16. Xinhua said 26 people were arrested and some of them had confessed that the riot “was organized and premeditated, aiming at undermining public order and misleading world opinion so as to sabotage the Olympic Games.” In the Shangri-la town of Zhongdian county in Yunnan Province police patrolled the streets and foreigners were barred from entering.

In Aba in Sichuan, where some of the worst violence occurred, residents were told to stay quiet. One resident told the New York Times, “If anyone outside asks you what happened in Aba, you should say there is nothing abnormal.”

As of early April, the Chinese government said it had found 176 guns, 13,013 bullets, 3,500 kilograms of explosives, 19,000 sticks of dynamite and 350 knives in searches at monasteries. Police reportedly confiscated 30 guns, 498 bullets, eight pound of explosives, knives, satellite phones, receivers for overseas TV channels, fax machines, computers and banners saying, “Tibet Independence” at one monastery.

Image Sources: Tibet Uprising.org, Xinhua, AP, Kadfly

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2015