MOSUO ETHNIC GROUP

The Mosuo are a small minority with some unusual ideas about sex, marriage and the way society should be organized. Most of China's 40,000-60,000 or Mosuo live in Yunnan and Sichuan province around Lugu Lake, a fertile farming area, and the town of Yongning. [Source: Lu Yuan, Sam Mitchell, Natural History, November, 2000, Maggie Farley, Los Angeles Times, January 18, 1999]

The Mosuo are a small minority with some unusual ideas about sex, marriage and the way society should be organized. Most of China's 40,000-60,000 or Mosuo live in Yunnan and Sichuan province around Lugu Lake, a fertile farming area, and the town of Yongning. [Source: Lu Yuan, Sam Mitchell, Natural History, November, 2000, Maggie Farley, Los Angeles Times, January 18, 1999]

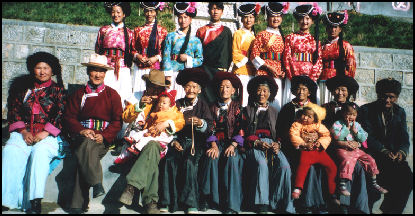

The Mosuo (pronounced MWO-swo) are also known as the Nari and Yongning Naxis. Most anthropologists regard them as a branch of the Naxi. Creators of a "female kingdom" or "daughters' kingdom", they have managed to keep alive their strong matrilineal customs in regards to marriage and family. A typical Mosuo family includes relatives of the mother's blood lineage — the maternal grandmother and her sisters and brothers, mother and her sisters and brothers, and mother's children and mother's sister's children. The father is regarded as an outsider. The status of women is very high. Elderly matriarchs are not only the head their family units they are also community leaders, overseeing production activities, the distribution of food and clothes and religious sacrifices.

According to the Lugu Lake Mosuo Cultural Development Association: “The Mosuo are, to many people, one of the most fascinating minority groups in China. Although commonly described as a matriarchal culture, the truth is much more complicated (and interesting) than that, and really defies categorization in traditional models. In general, it is true that Mosuo women take a leading role in the family (owning property, making business decisions.); and that women have more power/autonomy in many regards than in many other cultures. But there are many non-matriarchal facets of their culture, as well. Of course, one of the most interesting – and famous – aspects of Mosuo culture is the practice of “walking marriages”, a practice in which couples do not marry, but rather women can choose (and change) partners as they wish. But modern depictions of the Mosuo as sexually promiscuous (particularly marketing of Lugu Lake as a “sex tourist” area) are misleading at best, and often damaging.

The Mosuo were never granted an official minzu (ethnic minority group) status by the Chinese state and not considered one of China’s 56 ethnic groups. One their ID cards they are listed as being Mongolian. One reason estimates of their numbers vary is because of intermarriage with other groups, including Han Chinese, and so there are many mixed blood Mosuo.

Lugu Lake lies between the town of Yongning of Ninglang County in Yunnan Province and Zuosuo of Yanyuan County in Sichuan. Surrounded by green mountains, it is 8,580 feet (2,600 meters) above sea level, making it the highest-altitude lake in the Yunnan province. It is also the second-deepest body of water in China, at some points deeper than 297 feet (90 m) and has a circumference of about 100 lis (50 kilometers). Known for it very clear water and fat fish, the lake has nourished the Mosuo and Naxi living around it for generations. The nearest city is a six hours’ drive away, See Lugu Lake Under LIJIANG AND NORTHERN YUNNAN factsanddetails.com

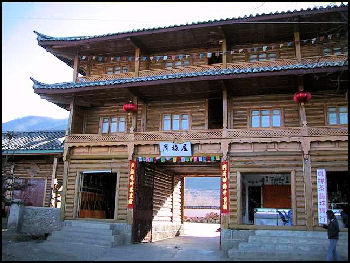

The Mosuo live in beautiful ancestral homes with wooden beams and subsist off barley, corn, potatoes and vegetables and raise pigs, chickens and goats. They often eat grilled fish in spite of the Tibetan custom against eating fish. They drink green tea and white liquor. Young women wear black headdresses lined with pearls. Older ones wear a simple turban. They also wear traditional long pleated skirts, felt blouses, and animal hide boots. The Mosuo have traditionally been extremely poor: Until recently their homes lack electricity, running water and flush toilets; and they make their own clothes. Once when Yang returned to her village to visit her mother she brought with her a can of expensive coffee. Her mother gave the coffee to the village pigs thinking the can was the present. The Mosuo don't record birthdays. Yang Erche Namu, a young Mosuo woman who a popular pop singer for a while, once asked her mother when she was born. "Before the rooster crowed," was her reply. [Source: Ross Terrill, National Geographic]

Websites and Sources: Mosuo Marriage second-congress-matriarchal-studies ; Book: “Leaving Mother Lake” by Yang Erche Namu reached the New York Times bestseller list in 2003.Book Chinese Minorities stanford.edu ; Chinese Government Law on Minorities china.org.cn ; Minority Rights minorityrights.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Ethnic China ethnic-china.com ;Wikipedia List of Ethnic Minorities in China Wikipedia ; Travel China Guide travelchinaguide.com ; China.org (government source) china.org.cn ; People’s Daily (government source) peopledaily.com.cn ; Paul Noll site: paulnoll.com ; Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science Museums of China Books: Ethnic Groups in China, Du Roufu and Vincent F. Yip, Science Press, Beijing, 1993; An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of China, Olson, James, Greenwood Press, Westport, 1998; “China's Minority Nationalities,” Great Wall Books, Beijing, 1984

Film: “The Women's Kingdom” by filmmaker Xiaoli Zhou won silver medal in the documentary category of 2006 Student Academy Awards and won the Best Editing Award from San Francisco Women’s Film Festival. Articles: 1) "Minority Report" in Time Asia reports on the affect of tourism on Mosuo living by Lugu Lake. 2) "Ladies of the Lake": Peter Ellegard of CNN Traveler reports from the village of Luoshui and meets Cha Cuo, the outspoken woman in "The Women's Kingdom" who chose a Han man for her walking marriage. 3) "The Sirens of Lugu Lake": Another travelogue by Jim Goodman. 4) "The End of Innocence": Laura Hutchison contemplates how a balance might be found between cultural identity and a new market economy. 5) "Leaving Mother Lake":Namu, the most famous Mosuo in China, ran away from her village as a young girl and became notorious for her many public relationships and untraditional views on sex and feminism.

See Separate Articles: NAXI MINORITY: HISTORY, RELIGION AND FESTIVALS factsanddetails.com ; NAXI LIFE, MARRIAGE, FOOD AND HOUSES factsanddetails.com NAXI CULTURE: MUSIC, CLOTHES AND PICTOGRAMS factsanddetails.com ; See Lugu Lake Under LIJIANG AND NORTHERN YUNNAN factsanddetails.com ;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Leaving Mother Lake” by Yang Erche Namu reached the New York Times bestseller list in 2003. Amazon.com; “Living in Shangrila: Tibetans and Mosuo in Northwest Yunnan” by Jim Goodman Amazon.com; “The Kingdom of Women: Life, Love and Death in China's Hidden Mountains” by Choo WaiHong Amazon.com; “Balancing Men and Women's Power and status: Parental Roles and Children's Socialization in Mosuo Matrilineal Families” by Yushan Zhong Amazon.com; “On the Shores of Mother Lake: A journey to the Tibetan border to meet the Moso people” by Francesca Rosati Freeman Amazon.com; Quest for Harmony: The Moso Traditions of Sexual Union and Family Life. by Chuan-kang Shih Amazon.com “A History and Anthropological Study of the Ancient Kingdoms of the Sino-Tibetan Borderland - Naxi and Mosuo” by Christine Mathieu Amazon.com

History of the Mosuo

Lake Lugu The Mosuo are descendants of Tibetan nomads. Many anthropologists classify them as a subgroup of the Naxi because the languages of the two groups are similar. The Mosuo don't like the classification. The Communists, they say, have used it to deny the Mosuo status as a distinct minority.

The Mosuo are believed to be descendants of the ancient Qiang, a people from the Tibetan plateau. The earliest reference to them come from the Han dynasty (206 B.C. to A.D. 222) and Tang dynasty (618-907) from Yunnan. They were also described during Kubla Khan's invasions of southern China in the 13th century. One Mosuo man told the BBC: "My grandpa told me that a long time ago, a platoon from Ghengis Khan’s army rode through this area on their way to battle and fell in love with the beauty of the lake. They decided to settle here, and that is how the Mosuo came to be,” Zhaxi said. [Source: Christopher Cherry, BBC, June 13, 2018]

Lugu Lake is so remote it didn't come under Communist control until 1956. Then for almost three decades it could only be reached after a week of trekking on foot or by horseback. Before road a road was finally was built to region in 1982 goods were brought in by mule train. In the early 2010s, Lake Lugu can be reached in 20 hours on public buses or in 9 hours in a jeep from Lijiang.

Some of Mosuo language is rendered in Dongba, the pictographic language of the Naxi and the only pictographic language used in the world today. The Mosuo language has no words for murder, war or rape, and the Mosuo have no jails. [Source: Frontline PBS.org]

On the links between Tibetan Bon religion and the Naxi (Na-Khi) and Mosuo (Mo-so) and how it shaped the Mosuo region Joseph Rock wrote In “The Na-Khi Naga cults and related ceremonies,” : “The banishment of the Bon religion in Tibet at the order of King Khri-srong -lde-btsan, who ruled approximately between 740 and 786 A.D. is possibly responsible for the Na-khi and Mo-so having become convert to Bonism… Most of the Bon went into exile, under insults were expelled to the most desolate regions on the periphery of Tibet. Among the names of the places to which they were banished occurs the name IJang-mo. Now IJang is the term the Tibetans have for the Na-khi and Mo-so. [Source: Rock, J.F.. The Na-Khi Naga cults and related ceremonies. IImeo. Roma. 1952, pp 2 to 4; Ethnic China *]

“Then there came the incarnation of the Yellow Sect from Chamdo to Yongning to convert the inhabitants to the Gelugba sect." The Mosuo of Zuosou "refused to be converted and until this day remained attached to the Bon religion....“As the Mo-so were suppressed by the Yellow Lama Church they retained only with great difficulty their primitive Bon rituals, and as they had no writing a great deal of their ritual has been forgotten, while in Zuosou land the primitive Bon cult gradually become modified under the influence of Bon priests from Nyarong who were personae non gratae in Yongning and the other converted regions, and who helped the Zuosou people to firmly establish a Bon Church with temples, lamas, dances., the same as is now found in Tibet and on the borders to the north of Yunnan. *\

Mosuo Religion and Funerals

The Mosuo practice Tibetan Buddhism, the ancient Tibetan Bon religion, animism and shamanism. Tibetan Buddhism entered the region around the 13th century and had a great influence on Mosuo life. Before the Communist era, at least one son from each family joined a monastery in Tibet, but at the time the son often also participated in the walking marriages customs (See Below). The Mosuo still conduct Bon cremation ceremonies and practice a form of shamanism they call Daba. There is a Bon temple on the east side of the Lake Lugu.

Christopher Cherry of the BBC wrote: The Mosuo believe in the idea of a Mother Goddess. This ancient religious system is mixed with the more recent import of Tibetan Buddhism, with many families sending a male member to become a monk. The Mosuo also have some unusual beliefs, such as the veneration of dogs. There is a myth that long ago, dogs had a lifespan of 60 years while humans only lived for 13. Humans and dogs agreed to trade lifespans, and humans promised to pay their respects to dogs in return. " [Source: Christopher Cherry, BBC, June 13, 2018]

The traditional Mosuo religion worships nature, with Lugu Lake regarded as the Mother Goddess and the mountain overlooking it venerated as the Goddess of Love. The Mosuo also practice Lamaism, a Tibetan variation of Buddhism. Most Mosuo homes dedicate a room specifically for Buddhist worship and for sheltering traveling lamas, or monks. The Mosuo have two central religious practitioners: Tibetan-style lama or shaman priests call daba that are similar to the Naxi dongba. The Mosuo practice two spiritual traditions: Tibetan Buddhism and and their traditional religion, called daba, a type of shamanism that has been influenced by Bon, the pre-Buddhist religion of the Tibetans.

Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote: “The Mosuo believe in numerous goddesses and gods. For them most phenomena of nature have their own spirits. They worship the Goddess of the Mountain and the Goddess of the Water as their main deities. They consider all the deities of the mountains to be feminine. Mountain Goddesses are by no means unique to the Mosuo. They are found among many other minorities of China and in other lands as well. Cults of the mountains have likely existed in China from time immemorial. Chinese people today still worship some sacred mountains that, although now considered masculine, were in earlier times feminine. [Source: Ethnic China *]

“The Mosuo also believe that the sky and the earth, the sun, moon and stars, the wind and the rain, the lightning and the rays of the sun, fire and other natural phenomena all have their own spirits. They believe that when people die they become ghosts. They have such a rich spiritual world that some researchers say that they believe in "800 gods and 3,000 devils". With so many divinities they must carry out ceremonies frequently to honor them. The Mosuo believe that the first and fifteenth day of every lunar month (or in some cases the 5th and 25th) are the favorite days of the gods to be active in the world; and they so choose these days to worship them.

According to the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”: Around Lake Lugu, the funeral is organized by the lama as well as by dongba. As soon as someone dies, the family informs relatives and neighbors. The body is washed. Bits of silver, tea, and butter are put into the mouth of the dead. Butter is also applied to the nose and ears. Linen bands are used to tie the body up into a squatting posture; it is then put inside a linen or white cloth bag. A cave is dug beforehand in the rear of the central room. The bag containing the body is put down into the cave, with its face toward the gate. The cave is covered by a plank or an iron pan, which is further covered by a layer of earth. It is the exclusive duty of the son or nephew of the dead to cover the plank or pan with earth. This is called the "temporary stay of the corpse," the duration of which is decided by the lama, but it should not exceed 49 days. During these days, relatives and friends bring oblations and offer their condolences. When the days are over, the dongba priest is invited to read the scriptures to open a way for the soul of the dead. At the same time, the body is taken out of the cavern and put inside a cubic wooden coffin. When the coffin is sent to the crematorium, eight lama sit cross-legged while reciting the scriptures. Then, the body is again taken from the coffin and placed on firewood for cremation. They bury the ash in a secluded place. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 *]

Mosuo Religious Rite and Festival: Walking Around the Mountain

Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote: “The most common activities to the Mosuo participate in to worship their deities are "to walk around the mountains" and "to walk around the lake". For the ceremony of "walking around the mountain" each family goes to a fixed place in the forest. Each family has their own particular spot, called suokuaku, along the waist of the mountain. There they burn pine leaves and perform obeisance or koutou to honor the goddess of the mountain, while reciting the appropriate prayers. They remain there until the incense is consumed, after which they extinguish the fire and return home. [Source: Ethnic China *]

“The activity of "walking around the lake", to worship the Mother Lake, is in honor of the Goddess of the Lake. When walking around the lake, they also stop at fixed places where they usually burn incense and revere the goddess. They usually spend about 10 hours in their circumambulation of the Lugu Lake, half of the time worshipping the goddess and the other half enjoying the festival. Among their mountains, the most sacred is Gemu Mountain, which is variously known as the Mountain of the Girl of the Sacred Eagle, or simply the Mother Mountain; or for her shape, the Lion Mountain. Traditionally the Mosuo walked around Lugu Lake on foot or by horse, but nowadays people can be found riding bicycles or even motorcycles. *\

“There is a myth explaining the origin of this cult. It relates that many, many years ago, a girl named Gemu lived among the Mosuo. She was famous for her beauty, and renowned for her ability to embroider. It is said that at the moment she saw a bird, a flower, or a butterfly; at once she could embroider them accurately. Such was her fame that numerous suitors arrived at her door each day requesting her love. But she was not interested. Her fame grew to the point that it reached the sky, and there even a god fell in love with her. He came down to earth riding on the wind, and took Gemu away with him to the sky. People on earth, surprised, asked him to liberate her. But the god demanded an offering of 9,000 pairs of white goats and another 9,000 pairs of black goats. We see the symbolism of the numbers here, because nine is the masculine number, and this was the offering demanded by this god, while seven is the feminine number. The people made this enormous offering to the god, only to discover that the god had deceived them and Gemu did not return to the earth in human form. She now resides in Lion Mountain and her soul became a goddess. In order to remember her, from then on people referred to Lion Mountain as Gemu Mountain, and honor her, especially when they make the ritual circumambulation of the mountain. It is said that sometimes she appears riding on a white horse.

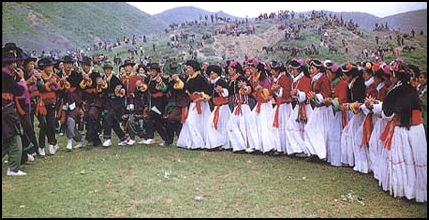

Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote: “Of the ceremonies involving walks around the mountain by far the most important is celebrated on the 25th day of the seventh month of the lunar calendar, to worship Gemu Mountain. On that day, everywhere on the mountain you can find the Mosuo, finely dressed for the festival, carrying food to celebrate with a banquet. Some walk, others ride horses. After making a circle of the mountain, each one goes to their suokuaku place, where they burn incense and carry out reverences to the mountain. They will hang a portrait of the Goddess of the Mountain, and they will pray to the goddess Gemu, asking her to liberate them from all misfortune, to let their grain grow, and to allow the people and livestock to prosper. They also worship the Goddess, offering her fruits, clean water, wine, and meat. [Source: Ethnic China *]

“When the religious rites finish, a great banquet begins, during which men and women, old and young, dance together in the Jiachati dance, enjoy horse racing, or take advantage of the festive atmosphere to find new love partners, with whom in the future they may establish an Azhu relationship. The festival goes on for several days. During those days people leave the village in groups for the mountains, dressed in their festival finery, accompanied by their Lamas and Daba priests. Every time they arrive at a suokuaku spot, they revere their goddesses, burning incense and pine leaves, spreading water and milk, and offering meat and wine to them. Then they hang on the branch of a tree some image of their totem and some prayer flags and papers. The Daba priest will recite poems and songs to the Goddess of the Mountain, and the Lama will also read some prayers to the mountain, playing the drum with one hand and ringing a bell with the other, while some younger men blow the conch. All these sounds mix in the festive air. Men and women should perform koutous to the four directions and the eight directions. When they have performed this ceremony in each of the soukuaku places, they return home. *\

Mosuo Rites of Passage

Mosuo have three rites of passage that accompany what they consider to be the three most events in a person’s life: : birth, adult initiation and death. Among the Mosuo a coming-of-age ceremony is held for 13-year-old boys and girls on the morning on the first day of the lunar New Year. All families with a child of that age make a a big fire in the fireplace. Boys stands by a "male column" and girls stand by a "female column" with one foot on a grain bag and the other foot on the fat of a pig. Silver coins are put in their hands, symbolizing the desire for good fortune in the future. Helped by her mother, the girl puts on a new skirt; the boy, helped by his uncle (mother's brother), puts on new trousers; the dongba then recites the prayers. The rite ends when the boys and the girls bow to their mother, uncle, and other elder members of their family. After the, the boys and birls are regarded as adults and are allowed to participate in adult activities. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Mosuo have three rites of passage that accompany what they consider to be the three most events in a person’s life: : birth, adult initiation and death. Among the Mosuo a coming-of-age ceremony is held for 13-year-old boys and girls on the morning on the first day of the lunar New Year. All families with a child of that age make a a big fire in the fireplace. Boys stands by a "male column" and girls stand by a "female column" with one foot on a grain bag and the other foot on the fat of a pig. Silver coins are put in their hands, symbolizing the desire for good fortune in the future. Helped by her mother, the girl puts on a new skirt; the boy, helped by his uncle (mother's brother), puts on new trousers; the dongba then recites the prayers. The rite ends when the boys and the girls bow to their mother, uncle, and other elder members of their family. After the, the boys and birls are regarded as adults and are allowed to participate in adult activities. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote: The first of the three major rituals that demarcate the life "is related to birth, and signifies incorporation into Mosuo society. The Mosuo celebrate this rite, which they call "choosing a name", immediately after the baby is born. This ceremony occurs on the same day of the birth if the child is a male, or on the following day if it is a female. A lama or a daba priest is usually in charge of this ceremony. The religion of the person in charge of the ceremony hardly affects the way it is carried out, although, the methods used to actually choose the name is different.[Source: Ethnic China *]

“When the ceremony begins, the lama or Daba reads the scriptures next to the fire. The mother or the female of highest rank in the Mosuo matriarchal family prepares a figure shaped from cooked rice that she places in the middle of a tray. In the center of that figure five pairs of chopsticks are inserted that represent the mountains and the pines. Surrounding the figure of rice a whole chicken, sausages, eggs and dried pork are placed on the tray. They burn incense around the offerings and then bring the incense sticks in before the priest who is reading the scriptures. This is a way of worshipping the gods and the ancestors. Later, the baby's mother or grandmother takes the child in her arms and, joining his palms in the Buddhist manner, places the newborn before the priest who will tap it softly on the head with a religious text while continuing to chant and pray. When he finishes his chants and prayers, he says out loud three times the name chosen for the newborn, and he anoints the head with oil, wishing the child a long and happy life. *\

“Then the tray with the offerings is offered before the old men. They take up the chopsticks three times while reciting auspicious mantras for the newborn. This is considered an offering to the gods. Later it is necessary to carry out the offering to the ancestors. For this the mother or highest ranking female places some offerings in a bowl and offers them before the ancestors, naming each one of them. When finished, she burns incense over the offerings that are then thrown onto the roof of the house to feed the crows. After carrying out this activity three times she goes to worship the gods of the fire, making offerings to them on and under the hearth. Finally she offers a chicken leg, a piece of pig and some wine to the biological father of the newborn. What is left is shared among all the participants. *\

Matrilineal family

“Before the proper ceremony has started, the priest has divined the name he will choose for the new born. In this the Chinese influence is apparent. To choose the name he keeps in mind the sign of the zodiac to which the mother belongs. Each sign is situated in a position that relates to the four cardinal points and the four secondary points. Among the Mosuo it is considered that the rat and the pig belong to the North, the dog to the Northeast, the tiger and the rabbit to the East, the dragon to the Southeast, the snake and the horse to the South, the goat to the Southwest, the monkey and the rooster to the West and the cow to the Northwest. The only difference between the ceremony directed by a lama or by a Daba is that the first will place in each direction the name of one of the four treasures of Buddhism and, combining them with the five elements (earth, wood, fire, metal and water) and the sex of the newly born, will provide a definitive name.If it is a Daba who presides, he will keep more in mind the hour at which the baby was born, and its relationship with the five elements, in order to choose an appropriate name. Once this ceremony is concluded the baby is considered to be a full member of Mosuo society.” /*/

Mosuo Matrilineal Society

The Mosuo are often said to have one of the world’s last matriarchal societies, but that is not correct. It is more accurate to call Mosuo traditions matrilineal,, meaning that kinship is based on relations with the mother or the female line. This means a woman lives with her brothers and sisters, her mother with her mother's brothers and sisters, and so on for women of each generation. All the family members are generations of women with their sons and daughters. Men still wield political power outside the family, but women are the heads of their households and make decisions about family resources. Wealth and property are passed through the mother upon death, giving Mosuo women a great deal of authority and freedom. [Source: Christopher Cherry, BBC, June 13, 2018]

Mosuo women have traditionally controlled many features of family and community life normally controlled by men: money, farming and religious ceremonies. Society is organized into matriarchal clans that take care of children collectively like in an Israeli kibbutzim. In traditional Mosuo matriarchal societies property and names are passed down from mother to daughter and disputes are settled by female elders. If the Mosuo word for female is added to a word it makes it stronger. If the word for male is added it weakens the word. The word for "stone" plus "female" equal boulder while "stone" plus "male" equals pebble. ‘Dabu’ is the word for matriarch of a family. She has traditionally been given the keys to the storehouse, symbolizing her role as he head of the household.

One Mosuo song: goes:

One Mosuo song: goes:

There are so many skillful people,

but none can compare with my mother.

There are so many knowledgeable people,

but none can equal with my mother.

There are so many people skilled in song and dance,

but none can compete with my mother.

According to PBS: “Given that Mosuo women make most of the major decisions, control the household finances, and pass on the family name to their children, many anthropologists classify the Mosuo culture as a "matriarchal society." But those who have studied these ancient societies are often at odds as to what to label them. Many prefer to call societies, like the Mosuo, "matrilineal" societies. In these cultures, the mother passes her name on to her offspring, and families live in clans that consist of at least three generations of women and the directly related men. Some anthropologists believe that in order to have a true matriarchy, women must also control sources of food and how it is distributed throughout the clan. As Matriarchies are chiefly agricultural societies, where goods are shared throughout the community, no-one person in the group is allowed to accumulate more wealth than another. [Source: Frontline PBS.org]

Men in Mosuo Matrilineal Society

According to PBS: “ In true matriarchal societies, the relationship of "father" is not important, since a child takes the mother's clan name and is raised by the members of the clan. Uncles tend to be the most important men in a child's life. [Source: Frontline PBS.org]

Christopher Cherry of the BBC wrote: Men still play important roles in Mosuo society, however. Traditionally, they were often away from the village, travelling in trade caravans to sell local produce. They would also be responsible for house building and fishing, as well as the killing of livestock. Most importantly, still today, while they are not responsible for their own children, they are financially responsible for the nephews and nieces living in their own households. [Source:Christopher Cherry, BBC, June 13, 2018]

Yang Zhaxi is a young musician who grew up in a very traditional Mosuo home, raised by his mother and his aunties and uncles. His biological father was very present during his childhood, however, and he remembers frequent trips together to pick mushrooms or gather firewood. His father still lives in the same village, and they maintain a strong bond. Really it depends on the character of the male. If he is kind-hearted, even though the marriage doesn’t work out, he would still take care of the kids, buy gifts for them and support their education. After all, the kids are his children even if they aren’t his responsibility,” Zhaxi said.

Mosuo views on love and marriage are being transformed by increased contact with the outside world. Young Mosuo are frequently attracted to the fairy-tale idealism of Chinese romantic movies, and more and more are choosing to marry in the traditional Chinese way, with couples cohabiting and taking marriage vows for life. Zhaxi himself has married outside of his tribe, to a Han Chinese, and lives with her and their baby, believing it is a ‘simpler’ way of life. At the same time, he is still responsible for his sister’s children.

Mosuo Women's Customs and Life

Mosuo women carry on the family name and run the households, which are usually made up of several families, with one woman elected as the head. The head matriarchs of each village govern the region by committee.The women do most everything. They raise the crops, fish, take care of the children, earn money. Help is provided by matrilineal kin. At night women gather around a fire and are assigned tasks for the next day by the senior woman in the village. Men are responsible for some heavy tasks such as plowing, clearing land, herding horses and hauling fish nets and occasionally helped out at stores and guest houses owned by the women. Mostly the sit around, play pool and watch the children. "The men here do nothing," a 24-year-old Mosuo woman told the Los Angeles Times. "Really we don't like them."

According to PBS: As an agrarian culture, much of the Mosuo daily life centers around tending to crops and livestock, with villages and households bartering between them for basic needs. A typical Mosuo house is divided in to four separate structures around an open courtyard. Traditionally, families share the building with livestock, and the living and sleeping areas are communal. With tourism and the modern world encroaching, some of this traditional structure is beginning to change. Electricity has now reached the more accessible Mosuo villages, which has brought satellite dishes and television — and the cultural ramifications that come with it. [Source: Frontline PBS.org]

Traditionally Boys and girls wear long gowns before the age of 13 years old. After their adulthood rite at thirteen, they begin wearing adults' clothes: skirts for females and trousers for males. Adult women like to wear red, blue or purple coast, which are edged with colorful cloth strips and sewed with two lines of buttons, and light blue two-layer plaited skirt with a white underskirt under it. The skirt reaches the feet. They also like to a tie red or yellow belt around their west and wear embroidered shoes made of black cloth. Young men braid their hair and coil it at the top of head or let it fall down below the head. Men between thirty and fifty wear black cloth hat or leather hat made by themselves. They like Tibetan clothes and adornments. For example, they like to wear Tibetan woolen hats and Tibetan boots, and big copper or silver earrings. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

Mosuo Families

A Mosuo family usually consists of two to four generations, with an average of seven or eight people. In some cases, a family has 20 to 30 members. A typical family consists of a mother, grandmother, sister, younger brother, older brother and sister’s son. The ideal household consist of a senior woman, her brothers, her younger sisters, her children, her sisters’ children and her sisters daughter’s children. The head of the family is usually an aged or a capable woman. She organizes sacrificial offerings. Work is divided according to age and sex. Property is distributed on an egalitarianism basis

Mosuo women have traditionally rarely taken husbands. Up until the 20th century marriage didn't even exist in Mosuo culture and their families didn't have husbands and wives. Women took lovers when it pleased them and often children had no idea who their fathers were. According to a custom known as the azhu (or friend) system, Mosuo women lived on their own and their the lovers were allowed to spend the night but not live with them. The man and the woman call each other azhu. Children could be produced in relationships that lasted for several years, or just one or two nights.

If a male boy and female are offspring of the same maternal ancestor of less than five generations, the azhu relationship is taboo; if more than five generations, there are no prohibition. Difference in age, seniority in the family or clan, and nationality theoretically have no bearing on the relationship. To renounce an azhu all a woman has to do is close her door and the the man stops coming around her house. In some cases a simple message is sent to the opposite side stating that the azhu relation is terminated. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 *]

During the Cultural Revolution the Mosuo were described as animals and their traditional customs were labeled as "decadent." The Mosuo were forced marry, abandon their religion and speak Chinese. Those that didn't get married and adopt monogamy were deprived of food. During this time the Mosuo held marriage certificates but quietly kept their customs alive. After the end of the Cultural Revolution, the Mosuo reclaimed their old ways and a slew of divorces ensued.

Mosuo's Unique Marriage Customs

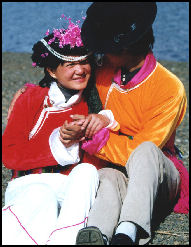

There are three kinds of marriage and sexual relations patterns among Mosuo people: 1) Traditional "walking marriage" (azhu, visiting marriage, zouhun, zoy hun, azhu humyin, Axia Azhu); 2) sisi ("walking back and forth", Axia Cohabitation) and 3) Monogamy. In a azhu humyin ("friend marriage") men live at home with their mothers and visit the homes of their partners after dark and leave before dawn.

After a coming of age ceremony, Mosuo females can choose their lovers — as many or as few as they wish within their lifetime. During these ‘marriages’, men visit the woman’s home upon invitation, and stay the night in a designated "flower room". Lu Yuan wrote in Natural History magazine: “Typical marriage is uncommon among the Mosuo: They favor a visiting relationship between lovers. Around the age of 12, a girl is given a coming-of-age ceremony, and, following puberty, she is allowed to receive male visitors, who may stay overnight in her room but will return in the morning to their own mother's home and their primary duties”. [Source: “Growing Up Sexually, Volume” I by D. F. Janssen, World Reference Atlas, 2004; [Source: Lu Yuan, Sam Mitchell, Natural History, November, 2000]

The lovers are called “Female Azhu" and “male Azhu". Men have traditionally visited during night and left in the early morning. The male typically left his shoes outside of the gate of the “Azhu House" to indicate that no other man should come. In recent decades, the Mosuo’s unique marriage customs have been replaced by more conventional marriages. According to the Chinese government: “After the foundation of the new China, by their inner active strength, the Naxis in Yongning reformed the original backward marriage customs gradually. Now the marriage relationship is consolidated day by day, and the big unitary matrilineal family is disappearing gradually.

Azhu: the Mosuo Friendship Marriage

If a man and woman fancy of each other, they present each other presents like a bracelet or girdle, and begin to share the same bed. Because they live and work separately in two families, the man go to the woman's home to visit and sleep after the night falls, and he leaves hurriedly to his mother's family early the next morning. Children born thereafter get the mother's surname and are reared by the mother's family. Men don't have any right or duty over their children. If the woman doesn’t want to see the man anymore or the man stops visiting, the "Azhu" marriage is over. Traditionally, the man kept up allegiance to his mother not his lover and was responsibilities upbringing of his sister's children, not his own.

[Source: Ethnic China *]

If a man and woman fancy of each other, they present each other presents like a bracelet or girdle, and begin to share the same bed. Because they live and work separately in two families, the man go to the woman's home to visit and sleep after the night falls, and he leaves hurriedly to his mother's family early the next morning. Children born thereafter get the mother's surname and are reared by the mother's family. Men don't have any right or duty over their children. If the woman doesn’t want to see the man anymore or the man stops visiting, the "Azhu" marriage is over. Traditionally, the man kept up allegiance to his mother not his lover and was responsibilities upbringing of his sister's children, not his own.

[Source: Ethnic China *]

Most of the men or women have six or seven azhu in their lives. The men usually begin to have an azhu at 17 or 18 and the women at 15 or 16. The Mosuo’s traditions originated thousands of years when many rural villages in China were governed by matriarchal customs. Some anthropologist say that the customs date back to a time when men were not present in villages because they were herding animals, fighting wars and serving as monks.

Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote: “Azhu doesn't mean that the women change their lover every night, although they could if they wanted to, but rather that the man has no right to the woman. Theoretically, the relationships between men and the women lasts only as long as their love (or their passion) lasts; and when their love ends, the couples separate. If the relationship between a man and woman is long, the children know who their father is, although that concept doesn't have the same meaning as it does for children of conventional marriages.

Christopher Cherry of the BBC wrote: What’s unique about Mosuo marriages compared to other many traditional societies is that relationships are allowed to run their natural course, since the female is not dependent on the male for income. Yang Congmu wove a belt for her lover soon after they met to express her affection, as was the tradition at the time. Now modern couples are more likely to gift each other flowers or an iPhone. After a while, the love faded. My husband didn’t really have anything to do with the children and he stopped coming round. In Mosuo culture, relationships are all about mutual affection. When it fades, we move on,” Yang Congmu said. [Source: Christopher Cherry, BBC, June 13, 2018]

Mosuo woman said the system "is good because we help our families during the daytime and only come together with our partners at night, and therefore there are few quarrels between us.” One 32-year-old Mosuo woman told the Los Angeles Times, "Outside Lake Lugu, marriage is like a business transaction. The women worry, 'Does he have a good job? can he take care of me? In our village, the girls are strong and take care of themselves. Everything we did is for love."

Azhu and Men

The Russian explorer Peter Goullart, who spent some time in the Mosuo area in the 1940s, wrote in his book Forgotten Kingdom: Lugu Lake "was a land of free love...Whenever a Tibetan caravan or other strangers were passing [their area], these ladies went into a huddle and secretly decided where each man should stay...She and her daughters prepared a feast and danced for the guest. Afterward the older lady bade him to make a choice between ripe experience and foolish youth." He wrote women used to tickle the palms of men they liked.

One man who bragged he "walked" with 26 women, a local record, told the Los Angeles Times, "Usually it is a secret buried deep in the bone. We don't even tell our brothers and sisters. The girl's family can hear the footsteps in the dark, but they never see the boy's face until there is a baby." He said he broke many hearts when he decided to break tradition and get married.

One Mosuo man told Natural History magazine, "'Friend Marriages' is very good. First, we are all other mother's children, making money for her, therefore there is no conflict between brothers and sisters. Second the relationship is based on love, and no money, or dowry, is involved. If a couple feels contented, they stay together. If they feel unhappy, they can go their separate ways. As a result, there is little fighting."

Azhu and Children

Mosuo house Any children who were born as a result of an belonged to the woman who gave birth to them and she was responsible for their upbringing. No effort was made to find out who the father was and if the father was identified he was responsible for taking care of the his child only as long as his relationship with the child's mother lasted. Traditionally, children stayed with their mothers and sometimes went through their whole lives without knowing who their father was. In her book "Leaving Mother Lake", Namu wrote: “In Moso, there is no word for father. There is no room for jealousy of fighting or bickering.” These days a small ceremony is held after a child is born to announce the father and, often the parents vow to stop seeing other people.

Traditionally, a mother was assisted in raising her children by her brothers. A man who lived with his mother helped his sister take care of her children. Even if a child and father were close, the father had no financial obligations to his biological child.

The child’s upbringing was taken care of by their mother’s with the most important guardian and figure of authority being the grandmother. Daughters and their children live, as well as the descendants of their daughters, live together with the grandmother. When a girl reaches adulthood she moves from the children's room to her own room, where she can receive her lovers.*\

Mosuo and Tourism

In the 1980s Lake Lugu had no schools or electricity. To reach the outside world required a seven day walk. In 1990s, many Mosuo villages got electricity. With it has come karaokes, television and tourists. A new road was completed in the early 2000s. An airport nearby, opened in 2015, has made Lake Lugu much easier to get to and more and more tourists are coming.

Now Lake Lugu is a tourist attraction. The provincial government has built numerous tourist facilities. A $2.5 million, 350-room hotel and a dance hall in the village of Luosui was planned or has been built. It is unclear what the long term effect of tourism will be on the Mosuo. But the women are tough and they survived the Cultural Revolution.

According to PBS: “With an increase in tourism to the area in recent years, many outsiders arrive expecting a "Shangri-La" of utopian free love. But this perception has been pushed mainly by the tourist trade, eager to attract more people to the area, rather than a reflection of true Mosuo culture. Women are free to take different sexual partners, and there is no stigma attached to bearing children with different partners or eschewing marriage. But more often than not, Mosuo women only take one sexual partner at a time, and often sustain long-term relationships with only one person. Misconceptions (or canny exploitation) of the Mosuo's sexual proclivities — depending on which way you look at it — have certainly fueled prostitution around Lugu Lake. But many of the women working in the brothels are more often Han Chinese women, from outside the region, who pass themselves off as Mosuo women. [Source: Frontline PBS.org]

Christopher Cherry of the BBC wrote: Tourists are bringing new beliefs and practices. Mosuo culture currently sits at a precarious juncture, caught between modernity and ancient tradition. Villagers living by the lake have built hotels for tourists. Some households with homes in good locations have become very wealthy now. Transport and other aspects have also become more convenient, and the Mosuo are exploring the outside world and experiencing new ideas. [Source: Christopher Cherry, BBC, June 13, 2018]

Namu, Famous Mosuo Singer

Inside a Mosuo house

Yang Erche Namu is a Mosuo singer, sex symbol and actress and one of the best known personalities in China. Famous for being famous, she left Lugu Lake, she says, when she was 14 with her mother throwing stones at her back and made a name for herself acting on television, designing lingerie, opening a “love hotel” equipped with Tibetan opium beds and publicly stating she preferred Western lovers to Chinese ones. A book she wrote, “Leaving Mother Lake”, reached the New York Times bestseller list in 2003. In 2007 she made headlines but went a little too far in the opinion of many when she proposed marriage to French President Nicholas Sarkozy on video tape.

Namu’s book brought a lot of attention to the Mosuo. It also brought a lot unwanted sex tourists to Lake Lugu. On that topic Namu told the International Herald Tribune, “The way we think about sex, it’s a Mosuo thing, not an outsider thing. It’s so pathetic, these guys who think, “I go to Lugu Lake, I get free sex.” And when they don’t get free sex, they get upset."

Namu also said a lot of Han Chinese tried to cash in on the Mosuo reputation. She said, “Lots of girls from Sichuan came. These girls know these guys expect free sex , but don’t get any. So they go deliver. They dress up in our traditional dress, and I hate that. It’s awful, disgusting.” Namu helped establish a Mosuo museum to help outsiders understand what the Mosuo are all about.

Han Chinese Romanticization of the Mosuo

The Mosuo’s matriarchal traditions are romanticized in sociological, fictional, and mass cultural productions by both Han and Mosuo intellectuals. In a review of “Mystifying China's Southwest Ethnic Borderlands” by Yuqing Yang, Yanshuo Zhang wrote: The Mosuo people have captured the imagination of many Han cultural scholars and sociologists for their perceived exoticism. The distinctive matrimonial practices of tisese (“walking marriage”) and unique gender norms of the Mosuo never fail to fascinate Han scholars and writers. [Source: “Mystifying China’s Southwest Ethnic Borderlands: Harmonious Heterotopia by Yuqing Yang (Lexington 2018); Reviewed by Yanshuo Zhang, MCLC Resource Center Publication, January, 2019]

Chapter 4 surveys the sociological literature produced by Han scholars and the inherent moralizing tendency in their investigations of Mosuo culture, typified in the discourses surrounding tisese. Though at times fantasized as a paradise of gender equality and sexual harmony, the Mosuo society and its marriage practices are sometimes condemned for encouraging “illicit and abnormal relationships” by a Han cultural “center” that upholds a Marxist ideology of civilizational stages. Chapter 4 brings to light these moralizing discourses as well as controversies in Han scholars’ characterization and representation of Mosuo culture, presenting the sociological accounts and intertextual debates on the nature of the Mosuo people and marriage system.

“Chapter 5 extends the debate from the realm of sociological studies to that of literary imagination. Using “The Remote Country of Women” as an example, Yang examines how its author Bai Hua, an acclaimed Han writer, questions the patriarchal state by unmasking the sensual, feminine ethnic borderland. It is here, Yang argues, that dominant Han culture finds its mirror image, or heterotopia, in the ethnic other. Chapter 6 studies how a highly controversial Mosuo woman, the sensational writer, performer, and fashion icon Yang Erche Namu offers up Mosuo traditions for mass cultural consumption. Namu became a spokeswoman for her people through her transnational journey of cultural negotiations. The chapter zooms in on the making of Namu’s hyper-feminine, hypersexualized public persona in her autobiographical writings, photographs, and public performances. These images and performances allowed Namu to self-orientalize her people and her culture; they also became the source of a national controversy by inspiring both moral judgements and cultural voyeurism.

Book: “Mystifying China’s Southwest Ethnic Borderlands: Harmonious Heterotopia by Yuqing Yang (Lexington 2018)

Image Sources: Autef.com; Lake Lugu.com; Ricardo Coler; CNTO; Joho maps

Text Sources: 1) “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China”, edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company; 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China *\; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2022