BAI RELIGION

Buddhism, Taoism and ancestor worship are practiced mainly by older Bai. A few traditions are kept alive from when they worshiped natural spirits and abstract heavenly spirits. The Bai have traditionally believed that illnesses were caused by the possession of evil spirits and were treated by shaman who used medicinal herbs, songs, chants and exorcisms as treatments and were paid with money or food. Women tend to worship publically at temple festivals while men engage in private ancestor worship at home. Many Bai temples were destroyed in the Cultural Revolution. Some have since been rebuilt. Missionaries made some inroads in the Bai regions but Christianity is viewed by both Bai and Chinese with suspicion.

Buddhism, Taoism and ancestor worship are practiced mainly by older Bai. A few traditions are kept alive from when they worshiped natural spirits and abstract heavenly spirits. The Bai have traditionally believed that illnesses were caused by the possession of evil spirits and were treated by shaman who used medicinal herbs, songs, chants and exorcisms as treatments and were paid with money or food. Women tend to worship publically at temple festivals while men engage in private ancestor worship at home. Many Bai temples were destroyed in the Cultural Revolution. Some have since been rebuilt. Missionaries made some inroads in the Bai regions but Christianity is viewed by both Bai and Chinese with suspicion.

The Bai religion incorporates elements of Buddhism, Taoism and Chinese folk religion with strong local beliefs, flavor, represented by the Benzhu, the belief in local lords or gods. Most Bai people are worshipers of "a communal god," but many of them, to varying degrees, also believe in Buddhism, Taoism and/or Christianity. The Benzhu religion is unique to the Bai people and unifying force among them but coexists amicably with other religions. Centuries ago cremation was the predominate custom.

Buddhism was introduced around the 7th century during the Tang Dynasty and was gradually accepted. Many temples have been built since then especially around Erhai Lake. Guanyin, the Buddhist Bodhisattva of Mercy, is an important figure in Bai myths. Chinese influence has also manifested itself in the importance of Daoism and Confucianism in the Bai religious scheme. It is very common to find Buddhist, Daoist, Confucian and Benzhu temples or shrines within a single Bai village, or even within a single temple complex or home. [Source: Ethnic China *]

The Bai worship their own protecting communal god (sometimes called an immortal). Almost every village has its own protected immortal, which is often a king from history or a local hero. are heroes. In most Bai villages religious life centers around the cult to the goddess Guanyin and their Benzhu cults. The cult to Guanyin incorporates elements of ancestral feminine cults, which usually includes rituals related with fertility and the protection of the children, as well as the worship of mythic and historical figures that existed before the arrival of Buddhism in Yunnan.

The Bai embrace Buddhist beliefs about the afterlife and reincarnation and believe that honored ancestors protect the living and ignoring creates malevolent spirits and ghosts. In ancient times, the Bai cremated their dead. Under Chinese influence they began burying the dead, sometimes in elaborate tombs. Under the Communists, cremation was encouraged to save land.

See Separate Articles: BAI MINORITY AND THEIR HISTORY factsanddetails.com ; BAI MINORITY CULTURE AND LIFE factsanddetails.com ; DALI: ITS ANCIENT CITY, BAI PEOPLE, LAKE ERHAI, CANGSHAN AND THE BUTTERFLY SPRING factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Tower of Five Glories: A Study of the Min Chia (Bai Ethnic Minority) of Ta Li, Yunnan” by C. P. Fitzgerald Amazon.com ; “Religious and Ethnic Revival in a Chinese Minority: The Bai People of Southwest China” by Liang Yongjia Amazon.com; “Peoples of the Greater Mekong: the Ethnic Minorities” by Jim Goodman and Jaffee Yeow Fei Yee Amazon.com ; Festivals: “Festivals of China's Ethnic Minorities” by Xing Li Amazon.com; “The Legend of the Torch Festival” Amazon.com; “The Three Temples Pilgrimage: An Ancient Ritual Festival of Dali, China” by Francis. Co and Francesco Cosentino Amazon.com

Bai Funerals and Superstitions

For the Bai the number 6 is the most auspicious. Gifts are given for birth of a child, the engagement of two young people, and the birthday of a senior person are typically money or items that come in sixes. In some cases a gift of 60 yuan might be gladly welcomed while 500 yuan might be refused. The reason for popularity of the number "six" is that the Bai are descendants of six tribes. In Imperial times, when the Dali kings gave gifts to Chinese Emperor each tribe gave its own gift so there were six altogether six. The Chinese Emperor in return gave six gifts, one for each tribe. Additionally in Bai language, the pronunciation of "six" is the same as that of "enough" or "handsome salary." [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 *]

The Nama branch of the Bai, which live near the Mekong River, still preserve the cult to the white stone—a culture and religion usually associated with peoples living further north such as the Qiang nationality. The Nama themselves say they a not sure why the white stone is important. Some of them attribute its sanctity of their ancestors' bones, which should not be moved, others; other say they are demons' bones, too dangerous to be moved, Yet others talk about legends of goats turned to stones or say white stones are a representation of the Fire God.

The Bai traditionally believed that worship of ancestors protected the living by linking them to dead spirits. Buddhism brought about beliefs in the afterlife and reincarnation. The Bai also believed strongly in ghosts and demons. Originally the Bai cremated their dead, but under Chinese influence, beginning in the Ming dynasty, burial become dominant and some were buried in elaborate marble tombs. At present the government encourages cremation in order to conserve land.

The Bai believe that the soul does not die with the body, but rather goes to the Kingdom of the Shades. To send it there, numerous ceremonies have to be performed after death. A rite of "seeing off the soul" is held after the death of a respected senior person. The Bai believe the soul will repeatedly come back to the house of the deceased. As a result on the first, third, seventh, thirtieth, and hundredth day after death, family, relatives, and friends perform of "seeing off the soul" ceremony in which family receive relatives and neighbors to dinner. It is believed that when the last of these are performed the soul will go to the "other side" once and for all to unite with the ancestors. *\

Benzhu Religion of the Bai

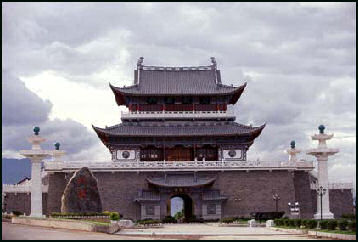

Dali main gate

Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote in Ethnic China: “The Benzhu, or Local Lords/Gods, religion is by far the most extensive spiritual tradition among the Bai and is one of their most unique characteristics. A fascinating amalgamation of history, fable and devotion, each village has its own god, who receives the worship of the people, and who protects them. In general these gods are historical heroes, warriors, sages or popular leaders, deified...It is believed that they are able to protect crops and livestock, to avert illness, and to bring peace and prosperity to the village. Because of this they are honored before any important event. [Source: Ethnic China *]

“The Benzhu religion preserves the memory of numerous legends and mythological characters associated with these legends, as well as what were probably historical figures. In every village around Erhai Lake the Bai people have developed a singular mythology around their own Local Lord, a mythology completely different from that of neighboring villages. This is a system similar to that of the City Gods Temples (chenghuangmiao in Chinese), common to every Chinese city until 1949. In the more remote places there are still vestiges of Bai primitive animism. It is not difficult to find places where different gods are honored, such as the God of the Mountain, the God of the Crops, the God of the Hunt, the Dragon King or the Mother Goddess of the Dragon King. The Bai believe that spirits can cause illness, but can also protect them. In some of the villages there are female shamans, sometimes with enough power to enter into trance, who still play an important role in the spiritual life of Bai villages.*\

“This belief in the lords of the place has been exuberantly developed by the Bai people, in a parallel (an maybe influenced) way as the Chenghuangmiao or Gods to the City developed among the Han Chinese, in a way that every village has its own local god, usually an historical personage that justify the domain of the inhabitants of the village over this territory; some times the first ancestor who settled in this place, or a hero who, saving the people in difficult times (war or catastrophe), performed a kind of re-foundation, achieving with his heroic accomplishment the right to inhabit this land, he and his descendants. The mythology surrounding this Benzhu cults is very rich, as every local hero or ancestor later deified, has his own mythology that justify his high position. *\

“In the Benzhu Temple the people perform ceremonies when some new member of the community is born, when he is sick, when he get married and when he dies. In this way we see that the cult of the Lord of the Locality in the Benzhu Temple is related to the continuity of the occupation of the land by the integrants of the village. The main task of these Benzhu or Local Lords is the protection of the people of the village. To ensure that he is able to fulfill his task, in every village has been developed an unique iconography related with the mythic history of the hero, as well as with local beliefs, tastes or traditions, in a way that, for from finding a regular set of images around the Lord of a certain locality, they are extremely varied. And even some of the deities that frequently appear in these temples, as the God of the Fortune riding a tiger, can be found at times stepping on a tiger, that recalls to this Buddhist iconography where the tiger is dominated by the Buddhist saints. Also frequent in these temples are the warriors guardians, usually at the two sides of the entrance, taking their horses for the reins, are extracted of historic episodes. *\

“Expressions of the religious feeling of the Bai are not found only in their temples, but are manifested in a wide variety of forms. Near the fields are usually erected shrines to honour the God of the Mountain, donor of rains and in this way necessary to the growing of the rice and vegetables. Some fields also have in the corner a kind of stone or vegetal shrine where incense offerings can be found. Inside the village, besides the gates paraphernalia common to the Han Chinese, simple offerings of incense can be found before shops and houses, big trees, and even in some places of the streets. *\

Bai Communal Gods

C. Le Blanc wrote in the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”: Each village enshrines and worships a certain god as the master and protector of the village. The villagers carve an idol made of wood or clay and put it in the temple. Most of the masters are famous personages of the kingdoms of Nanzhao or Dali. Some are part of their respective myths, while others are gods related to agriculture. After the 9th century, Buddhism became prevalent in areas around Er'hai Lake. The stone relief sculpture of the Buddha and of the Kings of Nanzhao in the grottoes of Shibao Mountain are a combination of Buddhism and of Bai traditional belief in the Master God. The Bai revere conch and fish. The Bai believe in the Fish God: whenever a fisherman catches a big fish, he puts it back in the water at once and prays while burning incense. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009]

In the Bai language the communal gods (the local lords or gods) are named "Wuzeng," or "Laogu (ancestors)," or "Laotai (ancestress)." In some places, the names "Wuzengni," "Zengni" and "Dongbo"—meaning of ancestor or master—are used. However, Bai worship is not simply ancestor worship, rather it is a form of community worship with its roots in farming sacrifice. The worship of communal gods was already formed in the Nanzhao period and was a religion of great importance in both the Nanzhao and Dali periods for the Bai people. Centuries the number of the communal gods has increased a lot. Now there are hundreds of them. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences]

For the Bai, the communal gods perform different social and spiritual functions: protecting the local village, taking charge of the destiny of the local people, maintaining people's happiness, bringing plentiful harvests, and keeping domestic animals healthy. Every Bai village has one or more shrines for their communal gods, whose clay or wooden figures are worshipped there. According to a census in 1990, there are altogether 986 shrines in Dali Bai Autonomous Prefecture.

Each village has its own communal gods; sometimes however, several villages share a common communal god. Different communal gods are in charge of different domains: some are in charge the business of "the infernal world"; some are involved more in the human world; some belong to the army of "the infernal world"; some affect illnesses and diseases; some influence domestic animals. Every communal god has his own title and oral or written legend stories.

Communal gods can be divided into the following types: 1) Those associated with natural objects such as stones, tree blotchs, water buffalo, monkeys, and white camels; 2) Traditional deities such as the god of mountains, the god of harvest, the god of hunting, the dragon king, and the god of the sun; 3) Heroes such as Du Chaoxuan, Duan Chicheng and Madam Bai Jie; 4) Characters in folk legend such as the Dali Nanmen communal god; 5) Kings and princes, generals and ministers, and ancestors such as Nanzhao, the King Nuluo and senior general Ge Luofeng of Dali kingdom; 6) People of other nationalities such as Zheng Hui and Du Guangting; 7) Gods of Buddhism and Taoism, such as Kwan-yin, Guan Yu, and Li Jing.

Worship of Bai Communal Gods

The Bai worship of communal gods has two basic characteristics: First, it is a sort of polytheism centered on the communal god. The communal god is the main subject of worship and other subsidiary gods and viewed as less important subjects. Subsidiary often have specific religious functions. For instance, the Offspring-offering Mother gives sons and heirs to a family; the god of fortune is in charge of wealth; and the dragon king is responsible for rainfalls. The second feature is that most of the worshipped gods are ancestors, or people who have done good things for ancestors of a given community. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities]

The basic features of Bai communal god worship are: 1) Nearly all people of the Bai ethnic group believe in some communal gods. 2) Every village has its fixed shrines and figures of gods for worship. The shrines are often independent buildings, which are grand in size and splendid in style. 3) There are people or organizations that are specially assigned to the supervision of public worship rituals. 4) Beside frequent individual worship rituals, every year there are two temple fairs with a set of fixed rituals: one in Spring Festival to welcome or see off the communal god, the other to celebrate the birthday of the god, or the day of his or her passing away. 5) There are worship rituals, the “Volume of The Communal Gods,” and a set of commandments and moral principles, such as loyalty to the nation, finial piety, respect for the old and affection for the young, hardworking and no misdoing.

In the two important worship ceremonies, every villager dresses up in their best clothes. A pig swine and chicken are killed and worshipers perform dragon and lion rituals, burn incense and paper, light firecrackers, worship of the communal god, and urge him to drive away ghosts and evil spirits, eliminate disasters, maintain peace and bring prosperity to the people of the community.

Celestial Ox of the Nama (Bai)

The Nama have been separated from other Bai for about seven centuries. They have preserved traditions lost among other Bai and have kept alive a nature cult similar to what the Bai practiced in the past, namely the belief that every phenomenon of nature has its own god. For the Nama, when a person dies, the body dies the soul remains the same as when the person was alive. [Source: Ethnic China]

One of the most interesting beliefs of the Nama is the cult of the celestial ox. The ox is considered to have the power to prevent disasters, to protect villages, insure peace with their neighbors, and promote the prosperity of their crops and livestock. The Nama think of the ox as an intermediary between human beings and the gods of the sky so they perform a ritual sacrifice aimed at enlisting the help of the ox to reach the sky to present their petitions to the gods. The sacrifice and the ceremony that goes with it is central to the spiritual and social life of the Nama. Everyone participates. Old men recount old times; women prepare the food; young men compete to carry out the sacrifice, while children play and observe the proceedings.

The sacrifice, presided over by a shaman, usually takes place during the sixth month of the lunar year. A yellow ox is unveiled. After some special ceremonies he becomes a celestial ox. For a few days the ox enjoys important privileges, such as moving about freely and eating whatever it wants. If some boy, not knowing the animal’s sacred status, hits the ox and is caught, the boy is required to stand before the ox and apologize and present a gift to the ox.

On the morning of the sacrifice, each family takes wine, rice and vegetables to the square of the celestial ox. Priests hang a red cloth from the ox’s horns that is supposed to show the ox the road to heaven and take the ox to the square, where four young men tie its legs. While the shaman burns incense and prays, the youths tie the ox to a tree, killing it with a knife through the neck. Then the shaman says: "Don't be afraid, it is not that we want your life, it is that the god of the sky wants you to ascend to the sky and report to him. This is a design of the god that we dare not disobey. Go to the sky. When you arrive, please tell the god good things about us. Help us in our affairs and request the god of the sky to protect our crops, our livestock and the harmony of the village." *\

Then the ox is skinned. The shaman is rewarded with the skin, the head and the bowels. The rest is distributed among the families. In the same square, people build fires and roast their meat and then eat it. Even people that don't usually eat ox meat eat it on this occasion because it is the meat of the celestial ox. In the 18th century, the Benzhu religion and cult of the celestial ox were often merged. In some villages, Benzhu temples had images of the celestial ox. In other places the Benzhu religion completely replaced the cult of the celestial ox. In yet other places, economic pressures resulted in a celestial pig being sacrificed instead of a celestial ox and the cult of the celestial ox was transformed into the cult of the celestial pig, with the pig assuming all the responsibilities and intermediary duties of previously held by the ox. In large, wealthy villages, sacrifices took place once a year; in the smaller, poorer ones, every two or three years.

Bai Festivals

Traditional Bai festivals include the Torch Festival, "Communal God" Festival, March Fair, Yutanhui and Raosanling. At most Bai festivals the people enjoy themselves singing and dancing. For special occasions hundreds people sit down and eat on raw pork mixed with garlic, chiles and soy while trumpeters and cymbal player play music to ward off evil spirits.

Worship Gathering at the Three Temples (Guanshanglan in the Bai language) is a carnival for the Bai people to entertain themselves during the slack season when there is little farming. Held on 23rd to the 25th days of the fourth lunar month, it is an occasion to welcome the coming of immortals from heaven, This event dates back to ancient times and was originally a religious ceremony. The three temples involved are the Chongsheng Temple, the Shengyuan Temple, and the Jinkui Temple. On the first day, people from the villages gather at Dali City and march off to Shengyuan Temple to pray for favorable weather and a bumper harvest. On the second day, they walk together to Jinkui Temple to offer sacrifices to a famous historic king, Duan Zongpang. On the last day, they go to Chongsheng Temple to pray for happiness and peace. The procession disassembles at a village named Mayi. \=/

Folk Song Singing Festival at Shibaoshan Mountain is an annual event that lasts a week, from the 27th of the seventh lunar month to the third of the eighth month. Thousands of young people from Jianchuan County, Yunlong County, Lanping County, Heqing County, and Lijiang County assemble at the four temples in Shibaoshan Mountain to sing folk songs. The four temples are Shizhong Temple, Baoxiang Temple, Haiyun Temple, and Jinding Temple. People play musical instruments and sing love songs, even in front of the solemn statues of Buddha. This festival is to commemorate a legendary pretty girl who lived 2,000 years ago who sung very well. Today, young people use the festival as an occasion to make friends or to find lovers. \=/

Protected Immortal's Day has links with Taoism and the Bai belief in communal gods. An immortal is the equivalent of a western patron saint. The worship of the protected immortal is popular with the Bai. In Dali, people worship immortals to a greater degree. Almost every village has its own protected immortal and people select a Buddha, a Dragon King, a king, a general, or a hero as their protected immortal. Celebration date differs from place to place. People say prayers, burn incense sticks, and kowtow in front of the statue of their protected immortal. They also sing and dance on this day. \=/

Bai Torch Festival

The Torch Festival is celebrated on the 24th day of 6th lunar month in July or August in n southwest China by the Bai, Naxi and Yi people. Participants light torches in front of their houses and set 35-foot-high torches — made from pine and cypress timbers stuffed with smaller branches — in their village squares. The Bulang, Wa, Lisu, Lahu, Hani and Jinuo minorities hold similar festivals but on different dates.

The festival honors a woman who leaped into a fire rather make love with a king. Before the village torch is lit people gather around it and drink rice wine. The village elders use a ladder to climb to the top of the torch as they distribute fruit and food to the villagers while they boisterously sing the "Torch Festival Song." The torch is then solemnly lit. The villagers light their torches off the village torch and sing and dance and eventually make their ways to their homes and light the torches there.

During the Torch Festival, Bai hang auspicious calligraphy and light torches. Torches are lit everywhere to usher in a bumper harvest and to bless the people with good health and fortune. Streamers bearing auspicious words are hung in doorways and at village entrances alongside the flaming torches. At night villagers, holding aloft torches, walk around in the fields to drive insects away, remembering a myth that recalls how in the beginning of history human beings went to their fields with torches to burn the plagues sent by the gods. [Source: China.org]

The Bai also celebrate the Torch Festival by wearing their best clothes and butchering pigs and sheep for a feast. Children dye their fingernails red with a kind of flower root. On the eve of the festival, people get everything ready for the big celebration. They set up a large torch about 20 meters high made of stalks and pine branches. On the top of the torch sits a large flag. Several small flags are fixed around the torch, printed with auspicious Chinese characters meaning peaceful land, favorable weather, bumper harvest, and abundant farm animals. Fruits, fireworks, and lanterns are hung around the torch. [Source: Chinatravel.com]

The Bai people in Dali practice a custom called "Splashing Fire for Blessing." When a person with a torch in his left hand encounters someone he points the torch at them, and sprinkles resin on the torch which produces sparks that are believed to keep away diseases and disaster. Other activities held during the torch festivals include bull against bull fights, wrestling and bonfire parties. The intent of the large bonfire is too keep evil spirits, harmful insects, diseases, and disasters away from the villages.

Third Month Fair

The Third Month Fair is one of the most important festivals celebrated in China, and one of the oldest. For many ethnic groups in southern China it is a major yearly event. For the Bai it is the most important festival of the year. One of the main gathering places is Mount Diancang, west of Dali city. There are dances, theater, sports, and horse races.

Celebrated from 15th day to 20th day of the third lunar month, the Third Month fair dates back to the Nanzhao Kingdom, when according to legend, the goddess Guanyin destroyed a demon that ate up people's eyes. In the old days, Han Chinese celebrated the third day of the third lunar month with the Festival of Xi. According to historical records: "It was the custom of the ancient people to pay homage to the water god and entertain themselves by the water on March the third of the lunar calendar." [Source: Ethnic China]

The Guanyin Fair, associated with the The Third Month Fair, is a traditional festival celebrated on the 5th to 20th day of the 3rd lunar month in late March or April at Taoist temples all over China that honors Guanyin (the Goddess of Mercy). The festival is a particularly big event in the Yunnan Province, where the Bai, Yi and Naxi people commemorate the arrival of Guanyin on Mount Cangshan and her victory of over the evil King Luocha. This fair attracts people from all over Yunnan and merchants and traders from all over southwest China. The Bai, Yi and Naxi people dress up in their beautiful ethnic costumes. In Dali, there is a three-mile-long Grand Fair in which vendors line up on the main road and sell jade and silk products, strange musical instruments, gongs, and local crafts.

Another big market fair, the Fish Pool Fair, is held on the northern shore of Erhai Lake. Held during the first week of the 8th lunar month, it features Bai wooden furniture, silver jewelry, embroidery and marble. Other festivals include the Butterfly Festival, Rao San Ling. In addition many villages have annual feasts with ceremonies and sacrifices.

Image Sources: Joho maps, Nolls China website, CNTO, Wiki Commons

Text Sources: 1) “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China”, edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company; 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China ; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2022