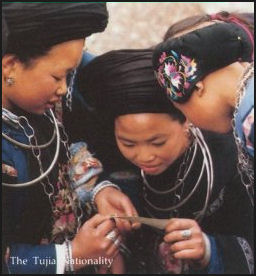

TUJIA LIFE

Tujia have traditionally lived in villages formed around a clan. In the old days, Tujia chiefs and officials had wooden homes with tiled roofs and carved columns, while ordinary people lived in thatched bamboo-woven houses. Today, Tujia live primarily in four kinds of houses: thatched cottage, adobe cottage, wooden wall house and Diao Jiao Lou; some Tujia people also live in stone houses and caves. A typical Tujia house has three parts: the main house, the side house, and the back house. The main house has three rooms; the middle one is the hall which has a Tun Kou in front. The side house is in front of the main house. The house behind the main house is the back house. Rich Tujia families have courtyard dwellings, the

front of which is called Men Lou Zi, and the middle of which is the yard. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

Tujia have traditionally lived in villages formed around a clan. In the old days, Tujia chiefs and officials had wooden homes with tiled roofs and carved columns, while ordinary people lived in thatched bamboo-woven houses. Today, Tujia live primarily in four kinds of houses: thatched cottage, adobe cottage, wooden wall house and Diao Jiao Lou; some Tujia people also live in stone houses and caves. A typical Tujia house has three parts: the main house, the side house, and the back house. The main house has three rooms; the middle one is the hall which has a Tun Kou in front. The side house is in front of the main house. The house behind the main house is the back house. Rich Tujia families have courtyard dwellings, the

front of which is called Men Lou Zi, and the middle of which is the yard. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

Western medicine, traditional Chinese medicine, herbal medicine and exorcisms are all used to treat illnesses. Before 1949 and after 1980 some religious practitioners have served as healers. Herbalists, following Han traditional medicine, have provided treatments for centuries. Modern medicine is now widely avialble. In the Xiangxi Autonomous Prefecture, the number of medical workers in Chinese and Western medicine rose from some 500 in 1949 to close to 6,000 in 1982. [Source: Lin Yueh-hwa (Lin Yaohua) and Zhang Haiyang, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

The Tujia economy relies mainly on agriculture. The main crops are rice, millet and beans. They are both valley and mountain-terrace farmers. Wet rice is the primary staple. Wheat, maize, and additional food crops plus cash crops such as beets, cotton, ramie, tea and tung trees are raised. The Tujia are known as skilled weavers and carpenters They produce batik cloth and elaborately carved beds. They are also employed in mining and light industry.

See Separate Articles: TUJIA MINORITY factsanddetails.com ; TUJIA CULTURE: EMBROIDERY, MUSIC AND SWING ARM DANCES factsanddetails.com; FENGHUANG AND MIAO, TUJIA AND DONG AREAS OF SOUTHERN HUNAN factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Tujia Language” by Philip Brassett & Meiyan Lu Cecilia Brassett Amazon.com; “The Art of Silver Jewellery: From the Minorities of China, The Golden Triangle, Mongolia and Tibet” by René Van Der Star Amazon.com; “Tujia Paintings and Woodcarvings in Guizhou and Their Development in the Qing Dynasty” by Yong Liu and Yanqin Tan Amazon.com; “Bizika Festivity (Dance Of Tujia)” (Album) by Wu Qiang Amazon.com; “Celebration by The Bizika Folks (Bi Zi Ka Huan Qing Hui)” by Wang Hongyi Amazon.com; “Ethnic Minorities of China” by Xu Ying & Wang Baoqin Amazon.com; “Handbook on Ethnic Minorities in China” by Xiaowei Zang Amazon.com; “China's Ethnic Minorities” by Xiao Xiaoming Amazon.com; “Encyclopedia of World Cultures. Vol. 6, Russia and Eurasia/China” (1994) by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond Amazon.com; “The 56 Colorful Ethnic Groups of China: China's Exotic Costume Culture in Color” by Xiebing Cauthen Amazon.com

Tujia Society

Lin Yueh-hwa and Zhang Haiyang wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “Social Organization. For Tujia — as for many Han — patrilineal clan ties, landlord-tenant relations, and gender were probably the most important factors organizing social stratification before 1949, though Tujia had comparatively weak parental authority. In the early 1950s the PRC government classified people according to their former economic status: for example, as rich, middle, or poor peasant. These rankings determined social stratification until after the Cultural Revolution. In Tujia areas the government classified individuals by ethnic group in the early 1980s, but from that time through the 1990s ethnicity had little effect on most people. |~| [Source: Lin Yueh-hwa (Lin Yaohua) and Zhang Haiyang, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Tujia Girl's Town

The patrilineage or lineage branch was led by someone of the senior generation who conducted ceremonies for the ancestors, mediated disputes, and was responsible for the behavior of the members. Lineage branches met at ancestral halls, sometimes drawing members from several villages. The village itself was also a community in which people helped each other in daily life, house building, opening of waste land, and defense. Wrongdoers would be ostracized by neighbors, in addition to suffering penalties from their descent group. |~|

Before the eighteenth century, known social control lay in the hands of indigenous rulers. Enticements to bring new lands under cultivation included exemptions from tribute. However, the penalties for lawbreaking could be severe, including castration. Under imperial administration, primary social control apparently shifted to clan leaders. Rules made in the clan hall applied to all clan members. After 1949, clan halls were abolished and the new socialist government took over social control. |~|

Ethnic conflicts are historically unknown among Tujia, probably because they were distinguished as an ethnic minority only in the 1950s. Local conflicts took the form of clan feuds, household or territorial conflicts, and fighting with bandits. Clan feuds reportedly were a problem as recently as the Cultural Revolution.

As is true throughout rural China, development and increased education in Tujia areas has led to a growing number of young people migrating to the cities often in their autonomous prefectures. This migration has had a destabilizing effect on the small rural villages, which depend on the younger generation to ensure their future — both economic and cultural.[Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 *]

Tujia Customs and Taboos

When a guest drops in, the Tujian host is expected to be very hospitable. Guests are usually welcomed with a gruel of sweetened fried flour. According to custom, the hosts break at least three eggs and drop them, one by one, into the boiling gruel. The Tujia hold big feasts for occasions such as weddings, funerals and the construction of a new house. See Food and Eating Customs Below

The Tujias have some unusual and distinctive household taboos. Young girls or pregnant women are not permitted to sit on thresholds, while men can not enter a house wearing straw raincoats or carrying hoes or empty buckets. Additionally, people are not allowed to approach the communal fire or say ostensibly unlucky things on auspicious days. Young women are not allowed to sit next to male visitors, although young girls can. At worship ceremonies, cats are kept away as their meowing is considered unlucky. [Source: People’s Daily]

According to the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,”“As soon as a baby is born, the father announces the good news to his mother-in-law. Before setting off, he should catch a chicken and bring it there as a gift. Depending on whether the baby is a boy or a girl, he catches a cock or a hen. In the western part of Jiangxi Province, if a girl is born, the father will grow peony in the courtyard. Each year he sells the peony roots and deposits the money in view of the girl's wedding. During the confinement following childbirth, the new mother eats a large number of eggs. A pile of eggshells thus retained will be dumped on the crossroad near the house. It announces to the villagers that the baby is a month old now and that mother and child are all safe and sound. A tile-like embroidered hat is woven for the baby. It means the baby will be rich and will live in a tile-roofed house in the future. In a family, if a woman does not get pregnant for a long time after the wedding, the couple will go to the temple to pray and make a vow. If a baby (especially a son) is born, they will bring sacrificial offerings to redeem their vow. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 *]

Tujia Families and Kinship

Tujia families are patrilineal. Small nuclear families are norm among Tujia though more complex households are not unknown and it is not unusual to have three generations living under the same roof. In the early 20th century, the elite reportedly preferred married sons to live with their parents until after the birth of their first child. Under such terms, a family went through a cycle of nuclear, stem, and occasionally joint families and then back to nuclear again. Among the poor, domestic needs for labor and the prohibitive cost of setting up new independent residences led to larger, more complex households. Many people who set up nuclear residences moved to urban areas, where they could more easily support themselves. In the 1990s people with sufficient means lived in nuclear households. [Source: Lin Yueh-hwa (Lin Yaohua) and Zhang Haiyang,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: Although Tujia were culturally influenced by Han, their inheritance system was significantly different. Han sons usually inherited equally or had preference given to the oldest son. Among Tujia the youngest son often inherited most or all of the property. Older sons received an inheritance share when they left the family home after marriage, but parents kept enough property to support themselves and their younger children.

Married men share in the household chores and women work but generally the position of women in the family is lower than men's. Womens' primarily duty has been child care. Foot-being was practiced by Tujia women. Despite this, Tujia women, like men, did heavy agricultural labor. The foot binding of peasant women was done later, less compactly, and less permanently than it was for elite women. Like Han, Tujia strongly prefer sons, something that can be seen in educational patterns. Even in the 1990s, not all families could afford to educate their sons. Nevertheless, most students were boys. This male bias is much more visible in rural areas and at higher educational levels.

Beyond the household the significant kin group is the patrilineage (lineage based on or tracing descent through the father’s line). In the past many immigrants adopted the surnames of the larger lineages, especially Peng, Tian, and Xiang. Even so marriage between people of the same surname is frowned upon. Clans have long been important among the Tujia. Most Tujia men know their genealogical history and the clans they were related to patrilaterally. According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: Before 1949 clans might worship ancestors together or provide schools for junior males. After 1980 Tujia often used kinship networks to accomplish social, economic, and political goals. Following Han custom, most men born before the Cultural Revolution (1967-1976) had a generational name shared by all the men in a generation. Individual Tujia men meeting for the first time could use it to locate their relative positions within the branches of a clan. In the 1990s some families began to use generational names again. |~|

Kinship terminology is of the Eskimo type. This means there is no distinction between patrilineal and matrilineal relatives. Parental siblings are distinguished only by their sex (Aunt, Uncle). All children of these individuals are lumped together regardless of sex This joint family system focuses on differences in kinship distance (the closer the relative is, the more distinctions are made).

Tujia Marriage

The Tujia generally had the freedom to chose their partners. In the old day they needed the blessing of shaman. Under Chinese influence, arranged marriages and bride price payments became more common and marriage became more a matter of economics. Parents would calculate the value of their children as potential partners, and choice became limited by wealth. Bride-prices have often been higher than dowry. Divorce is rare and considered improper. This was true throughout the 20th century except immediately after China's 1950 Marriage Law, which allowed for the easy dissolution of earlier arranged marriages. Remarriage after such divorces and after the death of a spouse was common.

Tujia a marriages are regarded as alliances between about the wife's family and the husband's family. Tujia people are very cautious about the marriage if the bride and the groom have the same surname. If they have the same surname, they may be of the same blood and marriage of the same blood is a big taboo. Even though the marriage between a couple of the same surname is in accordance with Tujia marriage rules, most Tujia people won't accept it. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

Residence with the husband’s family after marriage is the ideal, but it also acceptable for the newly married couple reside on their own separate from both the husband's family and the wife's family. In the past, cross-cousin marriage was preferred, and the maternal uncle could claim or renounce his right to have his sister's daughter as daughter-in-law. Today, the maternal uncle's blessing to a marriage of a niece is still considered important. These days the approval of the shaman is generally no longer required for a marriage to take place. Some old customs such as levirate marriage (in which a man is obliged to marry his brother's widow) still be found today.[Source: Lin Yueh-hwa (Lin Yaohua) and Zhang Haiyang, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Before the practice was outlawed in 1950, child marriage were common. Some young women had their feet bound as girls after their future mothers-in-law sent the binding cloth as a gift. Girls usually were raised in their natal families and transferred to the husband's family after puberty. Some very poor families practiced a form of tongyangxi marriage, sending a daughter to be "adopted" by her future husband's family a few years before the wedding. In the 1990s many young adults still consented to arranged marital introductions. |~|

Tujia Courting and Wedding

At one time, courting involved a great deal of singing and dancing. Today young men and women have the freedom to seek boyfriends and girlfriends. They may seek their partner in various kinds of meetings and occasions. A traditional wedding is preceded by a gathering in which the friends of the bride sing songs to the bride lamenting the marriage. [Source: People’s Daily]

Dating traditionally started with gift giving and antiphonal singing (alternate singing by groups of of male and female singers). If a boy and girl liked or loved each other, they exchanged gifts to symbolize their affection. The girl often gave the boy a piece of brocade, and the young man gave her a piece of fur. On a selected day of 6th, 7th or 8th lunar month (between June 26 and October 21 on the Western calendar), a "Girls' Meeting" was held. Women sing and dance at the same time. Often the all women of the village participate, wearing their traditional costumes. Meetings and lovers' rendezvous are a big part of the event. [Source: C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 *]

One week before her wedding, the girl begins her tearful singing. The words in her songs express her grateful feelings to her parents, her unwillingness to leave her family, her trust that her brothers and sister(s)-in-law will take good care of her parents, and her curse for the woman matchmaker, if any. Her parents, relatives, friends, and especially the girls of the same village participate in the tearful chorus. Their feelings are genuine and heartfelt.

“On the day of the wedding, a team from the young man's house comes to the bride's house; the bride's family and friends have already placed a table obstructing the entrance. Antiphonal singing or talking begins. If the bridegroom's side wins (which is usually the case), they are welcome and the table will be removed; if they lose, they are allowed to creep beneath the table to enter the house. They then accompany the girl to her fiancé's house. The ritual is lively and humorous. *\

There are a number of superstitions attached to a Tujia wedding. If you smoke a pipe of the husband's family, you are saying his family will make a fortune. If you take one cup of tea of husband's family, you are saying they will become even wealthier. If you drink a glass of wine of the husband's family, you are saying they will enjoy good wine for generations. In the "crying for the forefather" ritual the right foot steps out of the mother's room and the left foot steps onto the forefather's hall. The bride says “I have to leave both my forefathers and my father; I have to leave my forefathers and my mother.” [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

Tujia brides can not sweep the ground at her parents house when she visit them for the first time after marriage because the Tujia think she might sweep away good luck. When the groom has his first meal at the home of his parents-in-law he cannot finish the big bowl of rice served specially to him and he cannot eat the two soybeans (a soybean here stands for a gold bean) put in his cup of wine because it will make them poor. A newlywed couple can not make love when they spend the night at the bride's parent houses. \=/

Tujia Cry and Marry Ceremony

"Cry and Marry" ceremonies —also called "crying for marriage", "crying for marrying the child" and "crying before the sedan chair" are traditional marriage customs of the Han Chinese, Tujia, Tibetan, Yi, Zhuang and Salar minorities. The crying ceremony of Tujia is regarded as both the grandest and most typical one. It is not merely an essential etiquette and procedure in a Tujia wedding day but has developed into kind of unique art form of the Tujia.[Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

The Tujia "crying and marrying" ceremony usually starts three or seven days ahead of the wedding. Sometimes it is held a half month, a month and even three months ahead of the wedding. In the beginning, the crying is off and on. When relatives, friends and neighbors present gifts to the bride, the bride cries in gratitude. The custom reaches its climax, from the night before the wedding to the next morning before the bride gets in the bridal chair. The crying during this period follows prescribed, traditional etiquette and includes the singing of special songs. The crying and singing content included "crying for parents", "crying for brothers and sisters-in-law", "crying for uncles", "crying for escorting guests", "crying for the matchmaker", "crying when combing hair", "crying for ancestors", "crying when getting on the sedan chair' and so on. Lyrics are either ones that have passed down from one generation after another, or ones created through improvisation by the bride and her "crying" sisters. ~

Ten sisters' accompanying singing is a unique Tujia custom that takes place before the wedding day. The bride's parents will invite nine unmarried girls in the neighborhood to their home, and they sit with the bride singing songs for the whole night. At one point the girls sit around a table, and the bride cries ten times, which is called a Put. Each time she cries a cook puts a dish on the table. When the bride finishes there are ten dishes at the table and nine unmarried girls take turns crying. After the ninth girl cries, the bride cr iesy ten times, called Collects, and the cook collects the ten dishes. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

The main theme of the “cry and marry” ceremony is for the bride to extend gratitude to her parents for bringing her up with the love and care and to express similar sentiments to her brothers and sisters. Some aspects of this theme is for the bride to show her dissatisfaction with marriage and hatred for the mismatch made by the matchmaker and so on. The “crying for the matchmaker” ritual— also called "cursing the matchmaker"—is one example of this. ~

In addition to the bride, her relatives and friends are expected to join the crying ceremony and they must also be skilled and experienced in this ritual. In the Tujia area at the foot of Buddhist Mountain, when a girl gets married, the hall of the bride's house becomes a singing arena and women relatives come and join the crying ceremony. Everyone in the village — old and young, men and women — cry together with the bride and sing antiphonal songs. ~

In the past Tujia people put great emphasis on "crying and marrying", because of the traditional belief that a family won't make a fortune if the bride doesn't cry at the time of her wedding and the more the bride cries, the wealthier the family will be. People even set the extent of "crying and marrying" as the criteria of a woman's talent, virtue and marriagability. The bride is has also traditionally been praised for her eloquence, her flowery, querulous and stirring words, her hoarse voice and red and swollen eyes. Conversely, if she doesn't cry at the time of marriage, she was traditionally sneered at. Therefore, a lot of Tujia girls have to learn to cry by imitating other brides and participating the crying ceremonies beginning at a very young age, as a kind of training. Before marriage, some families even ask "experts" to teach their daughters the art of crying. ~

Tujia Villages and Houses

Tujia have traditionally lived in villages with 100 to 1,500 people, residing in 20 to 300 households, placed at the foot of mountains or on lower slopes near a water source. Traditionally, Tujia houses were shaped like "sitting tigers" — a custom probably related to their worship of the white tiger. Whenever they built a house on the slope, they built a platform first. The back side of the platform lay directly on the slope, while the front side was supported by wooden stilts. These days, Tujia typically live in Chinese-style two-story houses with tiled roofs and a central room where ancestors were worshiped. Separate buildings are used for storage and keeping animals.

According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “Larger settlements cluster around rivers and in basins, but many settlements are in rugged terrain. Although the people living there were poor in 1996, the numerous elaborate sarcophagi and mausoleums showed that once it had been wealthy. Historically, the poorest settlements consisted of wooden and/or mud-built extensions to small caves or a series of houses within vast caves. The PRC government has periodically moved people from caves to houses, but some poor families prefer caves because they are cooler in the summer and warmer in the winter. [Source: Lin Yueh-hwa (Lin Yaohua) and Zhang Haiyang,“Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Before 1949 many Tujia lived in tile-roofed wooden houses with a central room surrounded by a kitchen and secondary rooms. Some houses were raised, providing space for pigs, cattle, and latrines underneath. Tujia architecture was well known for a special form of wooden house, which is shared with several other southern minorities, that projects over the ground or water on several logs. Later, wood became scarce. By the 1990s, most homes were poured concrete structures.

Tujia Food and Eating Customs

The staple foods of the Tujia are rice and maize, with urban Tujia eating more rice and rural Tujia eating more corn. The Tujia sometimes eat wheat, sweet potatoes and yam. Meals tend to be simple and usually three meals a day are eaten. Tujia food has a unique sour and spicy taste. Sticky rice baba is one of most popular Tujai food. Rice is mixed with maize flour and steamed, producing a dry, colored cooked rice, which is often consumed with vegetable soup. Chicken, duck, goose, and pork are the main sources of protein. During the Spring Festival, wild game is added to the regular dishes. Drinking is popular. Tea culture and drinking is very much alive. Iron ware, wood ware and bamboo ware used in Tujia dining and cooking are all very special. [Sources: Chinatravel.com \=/; C. Le Blanc, “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 *]\

Guests to a Tujia house are typically served a bowl of sticky rice rum and a bowl of Tuan San in boiled water then treated to a big feast. When a guest is invited for tea, he is usually offered oil tea, Yinmi, Tangyuan, or a half-cooked egg. According to the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” the Tujia host breaks at least three eggs and drop them, one by one, into the boiling gruel (numbers three and four are regarded as lucky; numbers one, two, five and more are regarded as unlucky). The host proposes three toasts after the guests' arrival and before their departure. If a guest does not drink, he should dip his middle finger into the wine three times, each time taking it out and snapping the wine off; this means the guest drank his fill and thanks the host for his kindness. If guests are kept for dinner, the main dish is a bowl of seasoned pork or chops covered by a big piece of fat meat. *\

Tujia people hold feasts for occasions such as weddings, funerals and the construction of a new house. According to their custom, each table should be served with nine, seven or eleven dishes. A meal with eight dishes is for a beggar and ten in Chinese (shi) is pronounced the same as stone (shi), which has a bad meaning. Tujia in west Hubei must serve the guests 3 or 4 eggs in oil tea as a treat. They think, one egg means to eat bitter, two eggs mean to blame, five eggs mean to destroy five kinds of crops, six eggs mean to pity someone with small positions, and 7, 8 and 9 eggs suggest the unpropitious phrase Qi Si Ba Wang Jiu Mian ( 7 and 8 is to die, and 9 is to be buried). \=/

During festivals, the host bakes glutinous rice cakes in the fireplace for the guests. If a guest takes a cake covered with ash, the host helps the guest pat the ash off the cake. If the guest does it pats it himself, it might be deemed that he thinks the house is unclean. During the meal, the guest may lay his chop-sticks in the form of a cross, indicating he is full. *\

Tujia Economy and Agriculture

According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “Before the eighteenth century Tujia utilized a mixed subsistence pattern of shifting slash-and-burn agriculture, hunting, fishing, and gathering. Tujia areas became integrated into the larger regional commercial economy after coming under direct imperial Chinese administration. Tujia increased the scale of rice farming and largely replaced hunting and fishing with animal husbandry. The eighteenth-century introduction of New World crops (maize, potatoes, and sweet potatoes) supported a population boom. [Source: Lin Yueh-hwa (Lin Yaohua) and Zhang Haiyang, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

During the Chinese imperial era, intensive sedentary farming supported a large landlord class. Tujia were both peasants and landlords. Since 1949 the PRC government has changed the farmland policy three times. In the early 1950s lands formerly owned by landlords were allocated to farmers. In the late 1950s all farmland became collectively held by communes. By doing agricultural work and other kinds of labor, families earned points that determined the distribution of food and other goods for consumption. In the early 1980s farmland was reallocated to individual households. National policy gave managerial authority to households, but ownership remained with the state. Modern farming technology arrived in the 1970s. In the 1990s near urban areas, women and elderly men generally farmed and young men usually performed wage labor or ran small business ventures.

The oldest known item of trade was salt. An ancient stone road winds north through the Wuling Mountains to salt-producing centers near the Yangtze Gorges. Under imperial administration commercial activities increased dramatically. Historically, the major trade routes were rivers. The Yangtze, one of China's most important rivers, flows through the northern Tujia area. Several rivers and their tributaries connect Tujia areas throughout the Wuling Mountains to each other, to Han areas, and eventually to the Yangtze River. These rivers were still used for transportation in the 1990s, though rail and truck transport became more important after the 1960s.

Tujia areas have traditionally exported mountain products, especially tung oil, timber and charcoal, tea, lacquer, mushrooms, and medicinal herbs. Opium farming was a big business in the 1920s and 1930s, as was tobacco farming after 1949. In the 1990s police were concerned about illegal drug production there. Tujia are now involved in coal mining and light industry. Most villages include people who are skilled weavers and embroiderers, tailors, cabinet makers, house carpenters, and masons. Weaving and embroidery are of high quality, and the patterned quilts and bags are especially beautiful. Tujia gunny cloth is sought after for its durability. |~|

Tujia have always participated actively in the local marketing system. Towns and cities have daily markets, and in the rural areas markets are held once every three, five, or ten days at the township government centers, attracting thousands or even tens of thousands of people from the area and farther afield.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: 1) "Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China", edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company; 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China *\; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, BBCand various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2022