QIANG SOCIETY

Qiang village

The Qiang have strict rules separating males and females. There are specific seating orders, rituals and even sleeping arrangements for men and women. Men are responsible for plowing, transport and other heavy work and preside over spiritual duties. Women do most of the field work. Both sexes share in child rearing duties and household chores. There is a tradition of matriarchal customs in Qiang areas, with women handling domestic affairs and men handling foreign affairs.

The mountain areas traditionally inhabited by the Qiang have long been associated with matriarchies. Before 1949 the area had a high percentage of female rulers, at least partly because of the expendability of male elites. However, the classical pattern involves the sharing of power between male and female rulers, with women managing internal affairs while men took care of "foreign relations." In some areas, power was sometimes passed from mother to daughter. This power was, however, always shared with sons and consorts. [Source: Gerald A. Huntley, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Qiang-language-speaking society have traditionally had a strong sense of egalitarian and they were not even terms for to government and class. Even under the tusi system, which was characterized by a hierarchy of strictly endogamous classes (including serfs and slaves), over 90 percent of the people were free farmers.

Villages and clusters of villages tend to be grouped by clan or people that believe they have a common ancestor. Justice is carried out both by headmen and elders, selected on the basis of kin and hereditary class. There is a tradition of blood feuds in Qiang areas. Fear of such feud was an important element of social control. Parties to disputes often left the community to seek refuge elsewhere. Today, many Qiang customs and language have nearly vanished, victims of modernization and pressure by Han Chinese to assimilate.

See Separate Articles QIANG MINORITY factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Research on the Ethnic Relationship and Ethnic Culture Changes West of the Tibetan–Yi Corridor” by Gao Zhiying Amazon.com; “Life Among the Minority Nationalities of Northwest Yunnan” (1989) by Che Shen , Xiaoya Lu, et al Amazon.com; “Highlights of Minority Nationalities in Yunnan” (1969) Amazon.com ; “The Yunnan Ethnic Groups and Their Cultures” by Yunnan University International Exchange Series Amazon.com; “Ethnic Oral History Materials in Yunnan” by Zidan Chen Amazon.com; “Tibetan Borderlands” by P Christiaan Klieger Amazon.com; “Yunnan–Burma–Bengal Corridor Geographies” by Dan Smyer Yü and Karin Dean Amazon.com; “Frontier Tibet: Patterns of Change in the Sino-Tibetan Borderlands” by Stéphane Gros, Willem van Schendel, et al. Amazon.com; “On the Margins of Tibet: Cultural Survival on the Sino-Tibetan Frontier”by Ashild Kolas and Monika P. Thowsen Amazon.com

Qiang Life

The Qiang are adept at making watchtower-like buildings. Many of their villages are comprised of blocks of stone houses. Some Qiang settlements are built along mountainside with the houses clustered together for defensive purposes. Some are built above cliffs or other natural features that provide defense. Jiarong villages typically contain a fortress with a tower and a Tibetan Buddhist temple. Illness is attributed to spirits, and is treated by exorcism and/or reading of scriptures. Traditional Chinese and Tibetan medicine is also used. [Source: Gerald A. Huntley, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

market stuff

Millet, highland barley, potatoes, winter wheat and buckwheat make up their main staple foods. The Qiangs drink a great deal of wine and smoke orchid leaves. The Qiang eat a kind of bread called "three blows, three hits." The bread is cooked in an open fire, and after it is taken out of the fire it is covered in ashes. One needs to blow the ashes several times, and then pat it several times, hence the name. Many rely primarily on corn for food. After the harvests, grey buildings look like they have yellow roofs — with the corn drying on the roofs.

Qiangs dress themselves simply and tastefully and some dress in clothes similar to that of Tibetans. Men and women alike wear gowns made of gunny cloth, cotton and silk with sleeveless sheep's wool jackets. They like to bind their hair and legs. Women's clothing is laced and the collars are decorated with plum-shaped silver ornaments. They wear sharp-pointed and embroidered shoes, embroidered girdles and earrings, neck rings, hairpins and silver badges. Traditionally, Qiang made their own clothes from flax, ox leather, wool, sheepskin or fabric. These days many dress like Chinese. [Source: China.org]

Qiang Families

Among the Qiang, unions between men and women have traditionally been weak while those between siblings have been strong. Sometimes unions between siblings occurred. Households are often created on a sibling basis rather a husband and wife basis with siblings sharing in the child rearing chores rather than husband and wife.

There are no lineages. House names provide a sense of family continuity, but these may not be passed on to children who leave. In a some Qiang-language-speaking areas personal names incorporate part of the name of the father or mother. Today many people (including virtually all of the Qiang in areas like Mauwen) have adopted Han surnames. Kinship terms reflect generation and sex. With the exception of terms for key individuals (father, mother, mother's brother) kin terms are extended to all members of the community. In some areas, cousin terms reflect age level but not sex. [Source: Gerald A. Huntley, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Gerald A. Huntley wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “ The domestic unit centers around a woman and her children, men being viewed as somewhat peripheral. Households consist of one such unit, although units associated with siblings may share a single household. Responsibility for child care is shared by all members of the family unit; if a woman moves out after bearing children, her children often remain behind in their natal home. Children are assigned simple tasks at an early age. Emphasis is placed on independence and self-reliance and physical punishment is rare.In many areas land and cattle are divided equally among all members of the family, including those leaving home. Individuals taking up residence are expected to bring rights to land and cattle with them (thus family fields are widely dispersed). An heir, often a younger child, is selected while the parents are still living. |~|

Qiang Marriage

Qiang women in traditional clothes

Romantic love has traditionally been valued and people enjoyed a fair amount of sexual freedom. In the old days there was no marriage. Couples either shared a household or they didn’t. Over time a system of bride-service was adopted and rituals to sanctify this arrangement were adopted. Bride-services varied in length. According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: There were few rules; people tended not to have relationships with close neighbors/kin, although unions of siblings sometimes occurred. Marriage, in the sense of a discrete event marking an individual's passage from one household to another, did not exist. A gradual transition may occur, with a young man performing bride-service, dividing his residence between two households. A ritual was sometimes eventually be held to formalize this relationship, although the living arrangement remained unchanged. Today old traditions are largely gone partly because of laws requiring registration of households and sanctions against unmarried parents, and partly because people are encouraged to view these old customs as backward. [Source: Gerald A. Huntley, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

Today, marriages are mainly monogamous and often are arranged by parents. Usually, the wives were several years older than their husbands. It was common for cousins to marry and for bridegrooms to live with their wives' families. It still is not unusual for brides to live in their parents' houses for a year or so after marriage. In Qiang society, younger brothers sometimes married their widowed sister-in-laws and elder brothers married the widows of their younger brothers but customs have been gradually discarded since the Chinese takeover of China in 1949. [Source: China.org]

There were many old customs related to marriage. "Kids Marriage" which meant that the two children were engaged when still young. Sometimes two babies were engaged when they were still inside their mothers’ wombs. There are some procedures on engagement. After getting marriage and having a baby, there is a celebration.

Sometimes Qiang were betrothed before they were even born and Qiang boys got married between the ages of six and seven. Qiang women have traditionally been much older than their husbands because they usually got married between the ages of 12 and 18. These marriage customs are dying out and many Qiang now don't get married until they are in their twenties.

“Mountain songs” are often sung for courtship purposes. They are often accompanied by circular dances that involved the exchange of songs between males and females. The mouth harp has traditionally been played by women to serenade their lovers. In some places men play a double-reed Qiang flute for the same purpose. Ancient Qiang wedding rituals include dancing to traditional music, planting saplings to symbolize happiness and throwing corn and millet over the crowd for good fortune.

Qiang Wedding

The Qiang wedding is divided into three steps that take place over three days: flowery night (also called "women's flowery night"), formal union and going back to bride's home. The bride's side plays the more important role in the events. Drinking wine at wedding is a custom for many ethnic groups and the Qiangs are no exception. The night before the Qiang wedding, the groom’s and the bride’s sides each host a banquet to entertain respective elders in their clan and suck wine together, which is called "drinking wine in unsealed jar". [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

During the “flowery night", the "red uncle"(matchmaker and master of ceremonies the wedding) makes a speech named "words for meeting the bride" which praises the characters of the two sides and the happiness of the marriage, emphasizing "the farmland and house property should not be taken into account and the marriage is good only if persons are good". The head of the bride's family make a speech with "Answering words", saying " the two families have been relatives since ancient times, and don't mention house and property. What we pay attention to is friendly feeling instead of betrothal gifts, and old relatives and family dependants are more intimate". The bride does obeisance to family gods, members of her own clan and relatives, and gives a basket of shoes, which have been made in recent years, to the master who presents thankfulness on behalf of the girl and distribute shoes to the elders and relatives. They suck wine to their heart's content and do the Shalang dance far into the night. ~

The "Formal Union", also called "Formal Feast", is a big ceremony for the wedding and is the grandest. When the bride's father offers sacrifice to the family gods, the bride begins to cry loudly, expressing her reluctance and regret at leaving her parents and relatives. When the bride is escorted by seven or eight bridesmaids and gets out of the door, relatives and friends sob with flowing tears and express their good wishes at the same time. When the bride reaches the bridegroom's village, the whole village is rejoicing. Several gun salutes are fired and firecrackers are set off fired at the same time. A band plays happy, loud music and villagers shout and jump for joy. In the wedding, the main exhortation of the relatives to the new couple is that "respecting the old and loving the young are your duty. You should be modest and amiable to others and shouldn't dispute with others. Raise your children and keep your house well. Establishing family property relies on diligence". ~

The third day is for "going back to bride's home", which is also called "thanking guests" in some places. It is the day that the bride takes her husband back to her parents' home to express appreciation to relatives and friends of the bride's side. The power of the mother's brother is conspicuous in this event. Under his instructions, village elders tell the newlyweds: "now you are married and things are not the same as when you relied on your parents before. You should not only be diligent and work hard, but also be thrifty when running the home". The guests leave after lunch, and members of the clan and people who helped with preparation of the wedding stay to have dinner, sing and dance happily in the bride's home. ~

Qiang Villages and Buildings

Gerald A. Huntley wrote in the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: “In Qiang settlements, “Houses are built in close defensive groups on the mountainsides, often in conjunction with stone towers 30-50 meters high. Villages vary considerably in size, averaging around twenty households; they may occur in clusters of two or three, surrounded by fields. Separate clusters are distributed at intervals of 1.5 to 2 kilometers along the valley walls below treeline, frequently above steep cliffs, with valley bottoms often being relegated to Han Chinese settlements. [Source: Gerald A. Huntley, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

The Qiang built watchtowers, stone-piled house, chain bridges, plank roadway (built along perpendicular rock-faces by means of wooden brackets fixed into the cliff) and irrigation works. In their towns and villages are passing-street buildings (riding buildings) “constructed among some buildings for the convenience of contacting.” Many Qiangs traditionally were farmers who worked as stonemasons during the slack seasons. The world famous Dujiangyan Project in Guan County, Sichuan which is still functioning and benefitting the public 1,800 years after it was built. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote in Ethnic China: “Qiang villages were designed in such a way that, by closing the narrow alleys that exist between the houses, the stone houses became a true defensive wall. Near the villages, there are usually some tall towers of imposing aspect, sometimes located on a small promontory, or at the junction of two rivers. These towers should not be mistaken with the stone houses of several floors where the people live. Sometimes there is a single tower, other times there are several towers grouped together. They usually are between 30 and 60 meters high. Inside they have floors built with wood, and an inner stairway that allow access to the higher floors. Although the stone walls are well conserved, the inner woods are already rotten in most cases. It is not known with certainty the time of their construction but their quality is very good. In fact, they have resisted several major earthquakes. Although their function is not known, some experts suppose that they had a defensive function. [Source: Ethnic China*]

See Dujiangyan Irrigation System Under ; NEAR CHENGDU: MOUNTAINS, ANCIENT IRRIGATION SYSTEMS AND ALCOHOL WORKSHOPS factsanddetails.com

Qiang Houses

The Qiang have traditionally lived in flat-roofed multi-story houses built of unwrought stones. The bottom floor is for animals, storage and compost. The second floor is for living. A third floor is for storing grain. The area is organized around a hearth, regarded as sacred and associated with strict seating arrangements. The third story contains a large open space used for threshing grain and large meetings. The house has chimneys. Smoke escapes through holes in the roof.

The Qiang live in blockhouses made of piled up stones of different sizes. Unique in style, solid and practical, these houses are two or three stories high. The first floor is for livestock and poultry and farm tools, the second is where people live and sleep, and the third for grain storage. Some of the houses were built hundreds of years ago and they usually have three floors and a plane roof.

A typical Qiang house is square with flat roof, outer walls made of piled up slab stones. Each of the three floors is about three meters high. The first floor is composed of wooden boards or slab stones which stretch out of the wall and become eaves. Bamboo branches are placed on the boards or slab stones, and these are covered by heavily-rammed yellow mud and chicken droppings. The roof is 0.35 meters thick, with troughs for drawing away rain water and snow melt. The roof makes the house warm in winter and cool in summer. The flat roof is a place for threshing, drying grain, making clothes, and old people to rest and children to play. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities]

The most important part of the house is, of course, the floor where the people live. Family life revolves around a fire that is considered sacred. The Qiang do not allow the fire to be extinguished throughout the whole year. Over it is a metal tripod, of sacred meaning for the Qiang. Also on the second are the tablets for the ancestors, to which family members pay respect during special festivities. On the roof of each house there is a small white stone, an important religious symbol of the Qiang. There, at the highest point of the house, it represents to the God of the Heavens. The Qiang people believe that it can protect everything under it. [Source: Ethnic China]

Qiang Roads and Bridges

Qiang traditional house

The Qiangs are skilled in opening up roads on rocky cliffs and erecting bamboo bridges over swift rivers. The bamboo chain bridges they have built and laid with boards, stretch up to 100 meters with no nails and piers being used. Some of the Qiangs are excellent masons and are good at digging wells. During slack farming seasons they go to neighboring places to do chiseling and digging. Their skills are highly acclaimed.

The mountains are high and the rivers are perilous where many of the Qiang live. Over 1400 years ago they created chain bridges from bamboo, wood and stone. Arched gates made of piled stones were erected at the two sides of a river. Stone bases or big wood posts were set up inside the gates and bamboo rope as thick as human's arm were tied on the base or post. These were sometimes composed of tens of ropes. People walked o wooden boards that were placed on the bamboo chains. Handrails over one meter above the surface of the bridge were fixed on the sides of the boards. ~

There are two kinds of Qiang roadways: wooden and stone. Wooden roadways are built in dense forest and are paved with wood mixed with mud and rocks. Stone roadways are built at the overhanging cliff by chiseling holes in the cliff and plugging in wooden boards into the holes. Dujiangyan Irrigation System (60 kilometers northwest Chengdu) was built between A.D. 251 and 306 and contains several dams, canals and water diversion schemes that turned this part of Sichuan into the "land of abundance." Dujiangyan is a UNESCO World Heritage Site

Qiang Stone Towers

Stone towers are called "Qionglong" in Qiang language. As early as 2000 years ago, they were recorded in "The Later Han Book on The Commentary of the Southwestern Yi" that "the Ran Man people lived at the foot of hills and they made house by piling stones some of which were over ten Zhangs (a unit of length, 1zhang=3.33meters)". [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

Qiang stone towers are built near villages. Standing between 10 and 30 meters tall, they are used for resisting enemies and storing grain and firewood and have four, six or eight corners. Some are 13 to14 stories high and made from thin slab stones and yellow mud. The foundation of the wall is 1.35 meters high and constructed of piled slab stones. The inner side of the wall is vertical to the ground, and the outer side inclines from the lower part up. The Qiang built these towers without the equivalent of blueprints, hang lines or support, frames. Instead they relied on their excellent skills and experience as stone masons. Solid and firm, they have been able to stand wear and tear and the test of time. "Yongping Fort" in Yong'an village of the Qiang Township in Beichuan County, Sichuan withstood several hundred of years of wind, rain and earthquakes and is still well preserved. ~

An article written by Du Lin and Li Binlin in the Sichuan Daily on July 12, 2001, reported: “In extant old Qiang villages, the Taoping Qiang village in Li County is the most typical one. History records show that it was founded 111B.C., which has had more than 2000 years of history. The Taoping village has eight entrances, which make a layout of the Eight Trigrams. There are 31 passages, which extend in all directions and connect every family. There are secret holes everywhere for shooting, which were prepared for resisting enemies in the past. Only two stone watchtowers are kept in the village both of which have 9 storeys and are over 30 meters high. Because they were praised by officials from the UNESCO, the preparing work for declaring world heritage has started.”

An article written by Du Lin and Li Binlin in the Sichuan Daily on July 12, 2001, reported: “In extant old Qiang villages, the Taoping Qiang village in Li County is the most typical one. History records show that it was founded 111B.C., which has had more than 2000 years of history. The Taoping village has eight entrances, which make a layout of the Eight Trigrams. There are 31 passages, which extend in all directions and connect every family. There are secret holes everywhere for shooting, which were prepared for resisting enemies in the past. Only two stone watchtowers are kept in the village both of which have 9 storeys and are over 30 meters high. Because they were praised by officials from the UNESCO, the preparing work for declaring world heritage has started.”

Professor Sun Hongkai, regarded as an expert on the region where the Qiang live, says that 2000-year-old documents from the Han dynasty (2,000 years ago) describes Qiang-style towers built in that region by the ancestors of the Qiang. In the Tang dynasty, travelers that visited the area also described these towers, called "Qionglong" at that time. Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote in Ethnic China: “Professor Sun has concluded that all the peoples that speak languages of the Qiangic branch, such as the Jiarong, Pumi, Muya, Ergong, Guiqiong, Namuyi, Shixing, Ersu and Zhaba (unfortunately not recognized until now as differentiated ethnic entities), built such towers, while other peoples that, though living in the same region, do not speak a language of the Qiangic branch, do not build them. Their linguistic relationship, their common architecture, and their cult to the white stone...have preserved a unique culture over centuries. [Source: Ethnic China]

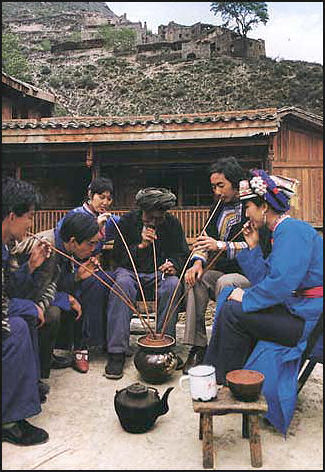

Qiang Fragrant "Sucking Wine"

The Qiangs have had a long history for making wine. According to legend, "Yu (the reputed founder of the Xia Dynasty) came from the western Qiangs". The first Qiang ancestor to make wine was Yidi who was Yu's official. Dukang (a person who was famous for making wine in ancient times) was Yu's descendant. Qiang men have a reputation for being heavy drinkers and have great capacity for liquor, but seldom get dead drunk and stir up trouble. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

The unique Qiang way of drinking is called “sucking wine.” The wine is made of highland barley, barley and corn, and is sealed in jars. When they drink it, they unseal the jar, pour boiled water in it, put bamboo tubes in the jar and suck in turn sharing a single tube or having one tube for each person. One drink’s according to one's capability and desire, with no pressure forcing and making one drink. Pure water is poured in while drinking, until the flavor becomes light. Sucking wine has a low alcohol content. When the Qiang drink, first the oldest person present says some lucky words known as the "words for proposing toast" that is composed of eight sentences with four words in each and are in rhyme. Drinkers have traditionally sucked wine in turn according to age. When persons of the same age suck wine together, each person put one bamboo tube into a jar and they drink together. ~

During the "Double Nine Wine Festival" men drink wine made of steamed by corn or wheat. Children and women often drink sweet wine added with honey. During festivals such as "the Qiang New Year", "the June Festival", "offering sacrifice to the mountain" and "the Fifth of the Lunar May" Qiang get together and sing and dance and drink to express affection. If they dance and sing in an open area, wine jars are put near the site; if they gather in a watchtower, they put wine jars under tables or at the foot of walls. If someone gets tired while dancing and wants to have some wine while taking a break, he or she suck wine from wine jars while chatting and watching the performance. ~

Qiang Culture

Qiang vest

Qiangs are good singers and dancers.Circular dances accompanied by exchanges of song between men and women are found, and the exchange of "mountain songs" is an important part of courtship. "Wine song," "plate song," "mountain song" and "leather drum" dances with accompaniment of gongs, tambourines, sonas and bamboo flutes are popular. The best-known handicraft is embroidery, usually in the form of intricately patterned waistbands and cloth shoes. |~|

Because of the long history and their relative isolation the Qiangs have a very old and characteristic culture and customs. The two earliest forms of literature are old poems and myths. These two forms of literature still have great influence and many outstanding works have been passed on for many generations. Most Qiangs can sing folk songs which are composed of four or seven syllables in each line and are similar to the four-character verse or seven-character verse in Chinese. The Qiang repertoire of songs includes bitter songs, mountain songs, love songs, wine songs, jubilant songs and mourning songs. Among the famous Qiang myths are "the Creation of Heaven and Earth", "the Forming of Valleys and Plains", "Creation of Human Beings", and "Dou'anzhu and Mujiezhu". Their stories about marriage between sister and brother and the shooting down of eight suns are believed to have a very ancient origin. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities]

Metal seems to be particularly cherished by by the Qiang. The Qiang have retained ceremonial ritual “armor” dance with weapons, and their women dancers still carry bronze bells that are sounded in time and rhythm to the male dancers’ drums. This folk dance is performed during the Qiang’s Zhuanshan Festival, when sorcerers call on the gods through a ceremonial drum dance. After the religious ceremony, people dance gaily to the sound of flutes, drums, and bells. Pieces of dough in the shape of the sun and half-moon are hung as offerings from an ox’s horns. Qiang women’s clothing items such as the collar, cuffs, sash, and shoes are often cross-stitched with circles, triangles, which are similar to that visible on some terracotta haniwa women’s clothing. For comparison, we take a look at how bronze and bronze bells were used in central China, particularly in Yunnan. Japanese bronze bells were almost certainly used in ritual or festive contexts, much like the context shown in the ancient mural below of tribal festivity in Yunnan, China. [Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website]

Qiang Musical Instruments

Qiang musical instruments include: 1) a harmonica made of leather or bamboo is used mainly by young men in their romantic songs contests; 2) the suona, a kind of Chinese traditional trumpet widely utilized in weddings and traditional festivals for the happy sounds it produces; and 3) gongs, cymbals and bells. The Qiang like the sounds of bells. The three kinds of bells more widely used among them are: copper bells, finger bells and shoulder bells. The mouth harp is traditionally played by women to serenade their lovers, while in some areas men play a double-barreled "Qiang flute." [Source: Ethnic China *]

Qiang flutes have been famous in China for 2,000 years ago. They were described in historical registers dating back time of the old Qiang (possible ancestors of today Qiang). Now the flutes are mostly made with a special mountain bamboo and consist of two pipes and six holes in each pipe. They are usually played by a single player who needs a long time to master its different sounds. It is played in festive ways, accompanying work songs, love songs and welcome songs. *\

Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote in Ethnic China: Qiang goat skin drums belong “to the long tradition of shamanic drums used by the shamans of north Asia in their shamanic voyages. There are many studies that relate the short cerebral waves induced by the drum to the ability to reach altered states of conscience. The Qiang have a tale about the origin of their drum that does not allow any doubt to the enlightened power of their drums. According to this myth, in remote times a goat ate the books that contained all the knowledge of the Qiang. To recover this knowledge they must beat the goat skin in the drum. *\

The Yao of Fuchuan County have also drums made of wood and goat skin, and a legend to explain the origin of their drums, clearly similar: "King Pan Gu, creator of the universe, went hunting one day and encountered a group of ferocious wild goats. They killed him and hung his body from a catalpa tree. Pan Gu's seven sons looked for him for seven days and seven nights. When they found his body they were so angry that they cut down the tree and pursued the goats until they killed them all. From the tree and the goatskins they made long drums, and used them in a dance to celebrate de avenging of their father's death. Yao villagers still celebrate King Pan Gu every July as their New Year." [Source: China's National Minorities I, Great Wall Books, Beijing,1984. P266]

Qiang Bamboo Flute

The most famous instrument of the Qiangs is the simple Qiang bamboo flute. Xushen wrote in "Explaining Words and Articles" in the Eastern Han: "The Qiang bamboo flute has three holes". Marong wrote in "Long Bamboo Flute": "The recent double bamboo flutes come from the Qiangs". "Mixed Record of Folk Songs by the Music Bureau" records that "Bamboo flute is an instrument of Qiangs". The "Music Book" written by Chenyang in the Song Dynasty says, "The Qiang bamboo has five holes." [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities]

The Qiang bamboo flute is associated with "Liangzhou” (a place name) and “ci” (poetry written to certain tunes with strict tonal patterns and rhyme schemes, in fixed numbers of lines and words)". One of the best examples of this style was written by famous poet Wangzhihuan in the Tang Dynasty. "The Yellow River flows long as if it is among the clouds. There is a stretch of lonely city and a mountain with 10 thousand rens (an ancient measure of length that equals to seven or eight chis). The person who is blowing the Qiang bamboo flute shouldn't blame the willow, because the spring wind doesn't blow across the Yumen Pass. (It seems that there is no spring in the north out of the Yumen Pass)". This poem has traditionally been recited by children who just began to learn to read and write in the past.

The modern Qiang flute is made of bamboo or bone. The bamboo is a kind of oil bamboo, which grows at the upper reaches of the Minjiang River and is cut into square pieces. The bone generally comes from the leg bone of a sheep or bird. The tube of present Qiang flute is 17 centimeters long and one centimeter in diameter, and has one reed and two tubes. It has six scales, is played upright and is usually played without accompaniment. The tone quality has been described as “bright and gentle, aggrieved, sweet and agreeable, melodious and expressive.” It is often played by shepherds in mountains. The old Qiang flute was not only an instrument but also part of a whip, so there is a saying — "blowing whip".

Qiang Dances

Dance is very important to the Qiang. Many aspects of their lives and culture are related to some form of dance. There are dances for festivals, harvests, reception of guests, adoration of the gods, funerals. It has been said that, "The dances impregnate each aspect of the life of the Qiang". They are not only vehicles by which they express their feelings but also a means relate and pass on their history and mythology. Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote in Ethnic China: “Dance serves as a means of expression capable of transforming any act into the realm of the sacred, and therefore is extremely significant. Dance preserves the communal memory of sacred procedures blessed by the ancestors. Any dance, among them, has an important ritual component. [Source: Ethnic China *]

Qiang dances have been divided into four basic types: 1) joy dances are the most numerous, including Salang dance or Yuechipu; 2) religious dances, are carried out primarily by shamans; 3) ceremonial dances, which are numerous and depend on characteristics and purpose of to the ceremony, such rites of passage or receiving guests; 4) meeting dances, which generally have of a martial character. /*/

Among the better known Qiang dances are the "Shalang dance" (a kind of circle dance), "Armor dance", "Leather drum dance", and "Langanshou". The "Armor dance" is a kind of traditional customary sacrifice offering dance, and was often danced at the funerals of famous military officers. Dozens of dancers wearing ox hide armor, leather helmet with pheasant's plumes and wheat shafts, carry bronze bells on their shoulders and hold weapons (mostly long sword). They separate into lines and dance like soldiers in battle. The roar shakes heaven and they are full of power and grandeur, which expresses vividly and incisively the unyielding and unconstrained national characters and reproduces vividly the rough and simple ancient local traits. The Dance of the Armor is intended to represent the departure of soldiers for a battle and their victorious return. It is only carried out during funerals, in order to demonstrate to the bad spirits the protection that the living relatives provide for their dead. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities]

Salang Dance and Qiang Religious Dances

Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote in Ethnic China: Of all the Qiang dances, the most famous is the Salang. According to legend, the Salang was inspired by shamans in the past. Nowadays, sometimes only women dance the Salang, perhaps a reminder of the times in which shamans were exclusively women. Although the Salang is considered a dance to enjoy during meetings and festivals, its important ritual components are still evident. Sometimes we see the dancers distributed in a semicircle around the fire, dressed in red skirts. [Source: Ethnic China *]

Salang is performed at the at most important Qiang celebrations: major festivals, marriages, and harvest celebrations. Sometimes the dancing goes on all night. Salang is believed to be among the oldest Qiang dances because it has developed into so many forms, including numerous variations carrying different meanings related to love, marriage, the harvest, and working in the field. The dance is similar to dances of the Naxi, the Mosuo and other ethnic groups in Yunnan and Sichuan. The type of Salang performed at funerals is slow and has specific movements meant to express respect for the dead. *\

Qiang shamans are expected to be present at religious dances whenever they are carried out. These dances include a great variety of forms depending on the function to which they are assigned. Jiang Yaxiong mentions the following as the most important: 1) The Dance of the Skin Drum is generally performed to cure a sick person or during a funeral. During this dance a shaman displays different relationships with the drum, which relate to communicating with the gods. 2) The Dance of the Cat has traditionally been performed during the time of the harvest. Shamans adopt the posture of cats (a sacred animal for the Qiang), whose movements are thought to expel possible calamities. 3) Dance of the Dragon of Rope in a kind of dance-fight between a shaman and a wooden-headed dragon with a rope as the body. [Source: (2) Jiang Yaxiong, Qiang Dances, “In Flying Dragon and Dancing Phoenix.” New World, Beijing *]

Qiang Economy and Agriculture

The Qiang practice hillside farming and herding. They grow buckwheat, barely, potatoes, beans and, below 2000 meters, corn. The area were they live is mountainous but well-watered and fertile. The fields are sometimes terraced and double teams of cattle are used for plowing. The Qiang used to grow opium as a cash crop but now grow apples, walnuts, pepper and rapeseed for that purpose. Some people earn money by collecting medicinal herbs The best known handicrafts are embroidery. Qiang hunt animals and collect mushrooms and herbs and also herd yaks and horses in mountaintop pastures. They probably come in contact with wild pandas more than any other ethnic group. |[Source: Gerald A. Huntley, “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: The area is cash-rich; an enterprising youth can earn more in one summer by digging herbs than a worker in the city can in one year. These sources of income are important because many areas must import food. Traditionally, crafts such as carpentry and blacksmithing were done by Han Chinese. Locals also tend to hire itinerant Han Chinese for odd jobs.

Rights to pasture are associated with the community, houses with the family unit, fields and cattle with individuals. Emphasis on the individual is balanced by a strong sense of community; fields are tilled and houses built by groups of neighbors and kin. In 1958 all individual rights to land were abolished and communities were organized into production teams. Land was redistributed, rights to use the commune's land being given in exchange for payment of light taxes.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Nolls China website,

Text Sources: 1) “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China”, edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company; 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Wikipedia, BBC and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2022