JINO MATRIARCHAL CULTURE

The Jinos highly respect their maternal uncles, who possess an extremely high prestige in Jino's social life. An uncle enjoys many items of traditional authority and responsibility, even surpassing those of children's father. When the nephew or the niece plans to find a lover and get married, they should first gain their uncle's approval.

Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote in Ethnic China and his book on the Jino: “Regarding the name “Jino” there are two alternate explanations. Some authors say that in their language “ji” means maternal uncle, and “nuo” means “coming next”. So “Jinuo” would mean “descendants of the uncle”, a reference that suggests in the near past they lived in a matriarchal society. The maternal uncle, the main man in a family ruled by a woman, is very important in matriarchal societies and the persistence of the uncles’ power in the family and society life indicates that in the past family power was shared by sister and brother and not between wife and husband. [Source: “China’s last but one matriarchy: The Jino of Yunnan” by Pedro Ceinos Arcones, 2013 Ethnic China *]

“The maternal uncle holds a very important role in each Jino life. He acts as protagonist in child naming ceremonies, betrothal and marriages; he even has the power to approve a marriage even if it is prevented by the couple’s parents (Bai and Zhang 2000: 32). As a protector of his nephew or niece he can take care of children born before marriage, and assist his nephews in case of weakness and sickness, tying a red string in their wrist to protect them and even chewing the food that they will eat when they feel weak *\

Other indication of matriarchal culture among the Jino include: 1) “The village deity is a deification of the foundational mother. 2) The zhuoba, the eldest person of the main clan in the village, occupies the highest position. His title means “mother of the village”, and the sacred female drum used at all village sacrifices and festivals is stored in his house. 3) The village deity is the ancestor of the zhuoba. As most of the Jino villages were established by women, this title “mother of the village” assigned to the zhuoba takes sense when we consider that these ancestral mothers transmitted their title and leadership to the elder of their daughters until the time when men took the title and office. *\

“4) Up until today the oldest woman is called Amo or mother of the village. 5) The fact that the elder’s council has seven members suggests that in the past it was an institution of the matriarchal clan society, when villagers were governed by the seven eldest women directed by the mother of the village. 6) The mother clan of the village had ritual and political preeminence over the father clan. *\

7) It could not be discarded that in the past the Jino lived in matriarchal long-houses. 8) As a family is protected under the house roof so women (maybe as traditional family chiefs) are protected under their hat, with the same shape. 9) Sometimes they also wear a kind of triangle-shaped cloth apron, a symbol of the women subjection to male power. 10) As the proverbs show: “mother runs the house” or “only the mother has the right to sacrifice hens to give its soul to the sick children.” This is a remnant of the traditional power of the female elders’ council in the matriarchal times. 11) They often say Abu Pila and Amo Pile. Abu means father, and Pila means a host that is often out, while Amo means mother, and Pile means hostess at home. *\

12) In the past, when children felt ill, shaman would be invited to dispel evil spirits. Traditionally, mothers must be at home in order for the ritual to be effective because only mothers had the right to “tie up the souls” of the children. 13) Before sowing the seed the Jino make a ceremony to call the Deity of Grain, when women of each family go the fields to sow the grain, and go back home. Then the main woman of each family, dressed in her best attires, meet in a cross-road where they will call together to the Deity of Grain. When they finish this ritual call they go back home, where each family would sacrifice a chicken that is offered, with wine, rice, tea to the grain deity while they pray to have enough food for the coming year. *\

See Separate Article JINO MINORITY factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “China's Last but One Matriarchy: the Jino of Yunnan” by Mr Pedro Ceinos Arcones Amazon.com ; “Restless Female Souls: The Jinuos” by Zhao Jie Amazon.com; Xishuangbanna: the Tropics of Yunnan” by Jim Goodman Amazon.com; “Social Change in the Economic Transformation of Livelihoods: Voices From the Upland Mountain Community in Southwestern China” by Wang Jieru Amazon.com; “Fog Agut: Jino the Kinship System” by Tang Xiao Chun (1991) Amazon.com; “Peoples of the Greater Mekong: the Ethnic Minorities” by Jim Goodman and Jaffee Yeow Fei Yee Amazon.com ; “The Yunnan Ethnic Groups and Their Cultures” by Yunnan University International Exchange Series Amazon.com

Jino Mythology and Religion and Their Matriarchal Culture

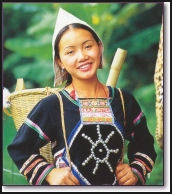

Jino girl

On the relationship between Jino mythology and religion and their matriarchal culture, Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote in Ethnic China and his book on the Jino: 1) In their myth Goddess Amoyaobai created the world and human beings. 2) moyaobai is also the goddess that taught civilization to human beings. 3) After the flood the new human beings surged from a gourd. A symbol of the womb. 4) To leave the gourd they needed the help of mother Apierer, who sacrificed her life for the people. 5) There were seven descendants of the couple that survived the flood. Seven is feminine number. 6) The Jino also have legends about a widow called Jiezhou who in the legendary past established the mythical village of the same name. [Source: “China’s last but one matriarchy: The Jino of Yunnan” by Pedro Ceinos Arcones, 2013 Ethnic China *]

7) Goddesses occupy the main positions in Jino mythology and religion, but they have no images or temples to focus their cult. All of their three main deities are goddesses. 8) Sacred to all the Jino are the three goddesses of shellfish. These deities are represented as shells, symbols of the female sex. 8) Below these main goddesses there is a legion of minor goddesses governing almost every natural phenomena and geographic accident. 9) In this world full of spiritual beings humans encounter with goddesses are not feared but actively sought. 10) Jiekaxi was other revered ancestress that taught them to distinguish edible plants (Wang 2004: 35). 34. Marriages between Jino “princesses” and Dai local chiefs must have occurred at a time when most of the Jino villages were possibly governed by the oldest matriarch. *\

8) The Jino send the souls of the dead to the ancestors’ land, but they have older traditions about a kind of Kingdom of Goddesses where they send the souls of deceased shamans. As it is well known that shamans must keep the traditions that guarantee their powers, it is possible that this land was older than the place where nowadays the souls of the dead are sent. 9) Shamans and witches are able to get their powers only thanks to their relationship with goddesses. 10) When the Jino build a new house, the ceremony of carrying the first fire is performed by an old woman 70 or 80 years old. 11) When the children get sick, only the mothers can sacrifice to the spirits to call their soul. *\

12) Jino relationship with the Goddess of the Grain, Zhaogaomizhe, basic to their feeding and survival, is directed by women. 13) Founding mothers were later deified as village deities, and their spirit said to inhabit the village deity pillar, from where they extended their protection to their offspring, and where they are worshipped in their main ceremonies or during difficult situations. 14) If a hunter gets any animal is because the goddess of hunt gives it to him; so, to get hunt it is natural that the hunter establishes a love relation with the goddess. 15) Maybe as a remnant of their former matriarchy the name of many villages contains the meaning of mother or woman. *\

History of Jino Matriarchal Culture

On the relationship between Jino history and their matriarchal culture, Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote in Ethnic China and his book on the Jino: 1) The earliest Jino settlements were probably two clans which had split from a moiety and then produced the ten or so daughter clans. This suggests that in ancient times the Jino passed through a matriarchal commune stage and probably also a stage of primitive communism in which between five and twenty families lived in a single long-house (Zhu 1989). 2) Zhuoba and zhuosheng leaders (village leaders) surged in this time and were carried by women, called zhoumi youke, “the venerated grandma that loves people”. 3) If the Jino migrated from northwest Yunnan their legends seem to fit better… because in this area the most powerful matriarchal tendencies are found. It is the home of the Moso matriarchal tribe. 4) It seems that the Jino are a Tibetan Burman matriarchal tribe which paired with a group of Zhuge Liang soldiers. [Source: “China’s last but one matriarchy: The Jino of Yunnan” by Pedro Ceinos Arcones, 2013 Ethnic China ethnic-china.com *]

5) Each of the three Jino branches was led in mythic-historical times by an ancestral mother. 6) Milijide, the ancestral mother of the Axi clan, is credited by establishing Situ village and giving names to mountains and valleys. As classical cultural heroes she knew where to find animals and taught the people to hunt and to gather edible herbs. She was considered a daughter of the Goddess of the Earth, she was the first shamaness with the ability to travel underground and to change the day into night and the clever inventor that for the first time used bamboo tubes to bring water from the mountain springs, and stone to sharpen knives. 7) Menbushade, whose name can be translated as "the fore-mother without father" was the ancestral mother of the Aha clan. She was also an inventor, priestess and protector of the sacred objects of the clan, especially the tripod, who is veneered in their main festivals, and she established their first matriarchal village. *\

8) “In the past all the clan leaders were women. They were the wisest shamans; they can divine and tell enchantments, they invented the stone knife, domesticated plants, and clothes…They were not goddesses but human beings as we” (Cheng 1993: 5). 9) The origin of political power in East Asia seems to be closely linked with the leadership exerted by female shamans. Sarah Nelson (2008) provides many instances when the origin of the big kingdoms and empires or East Asia is linked to the power of female shamans. 10) The circumstances which led to the establishing of the village is remembered in some villages’ name, as Badou or “the place where we stopped because mother’s breast ached”, Babou or “the village built by our foremother”, Bagui or “the village inhabited by the young women without fathers”, Shaoniu or “the village of girls without fathers” as legends say it was established by a girl who has no father, Aema or “the low village of the women without fathers” (Zhao 1995). *\

11) The leaders of the village would be called “mothers”, or even youka or grandmother in some places, even when their gender changed in an unknown historical moment. 12) These mothers are assisted by a council of seven members (the feminine number among the Jino and other cultures). 13) Kingdom of the 800 maid. Almost nothing is known about this kingdom or its hypothetical situation, but due to the fact that the Mongols traveled through this area in their way to conquer Burma and the Jino could be one (maybe not the unique) of the matriarchal societies there, it is possible that these Kingdom of the 800 maids referred to vague news received by the Mongol generals about matriarchal peoples living beyond the mountains through which they opened their way. *\

Jino Matriarchal Society Changes to a Patriarchal One

During the history of human society, the "consecutive naming system between father and children" is one important mark of the destruction of matriarchy and the establishment of patriarchy. This historical and cultural phenomenon still exists in Jino's present social life. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities]

The Jino have several myths that narrate how the matriarchal society was transformed into a patriarchal one, transition that the experts consider happened about 300 years ago. Their former matriarchal society kept, however, some of its main characteristics until 1950s, when they still had ancestors, name and foremothers in common, as well as cemetery, cult and ceremonies related to the same ancestress. [Source: “China’s last but one matriarchy: The Jino of Yunnan” by Pedro Ceinos Arcones, 2013 Ethnic China *]

If the patriarchal transformation of the Jino society did occurr around 300 years ago, then it coincided with a tumultuous period in regional history that has been be framed in the efforts of the emperor Yongzheng to obtain an effective control of the border and minority regions, which led Chinese traders and migrants to an increasing contact with the Jino. Sometimes Dai local chiefs established alliances with the heads of Jino clans or villages through marriage with Jino women… These notices of marriages between local princesses and foreign kings could be related with Tibeto-Burman tradition of the transmission of the political power through the marriage with the daughter of the chiefs. *\

Jino dance

Breaking the Jino Father-Child Naming System

The Jinos' sense of family name is quite vague, but they generally adopt a consecutive naming system between father and children while choosing a name for children, that is, choosing the last pronunciation of father's name as the first pronunciation of children's names, and so on so forth. Names of family line “Jieyou-Youbao-Baojie-Babaojie -Jieyue-Yueba-Basa-Sajie- Jiebaila-Bailayue-Yuezi— serve as an example. However, this system at present is not that strict. Names can be consecutive repeatedly (but avoiding the repetition with people alive), and the discontinuance has become a common thing.[Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

Reasons for the discontinuance are mainly is desire to break the connection after a child's incurable disease. The parents choose another name for the child. If it is an infant, its name is consecutive with that of the shaman, for it is said that the shaman's name could frighten the devils. But the name is not that of the shaman himself. It is the general name of the shaman-"Bailabao" and the specific repetition is also different from common ways, for it repeats the first two characters of "Bailabao", that is, "Baila". ~

The second circumstance for the discontinuance is that the child's brother or sister had died young before the child's birth. The parents are worried new child will follow its brother or sister, and an effort is made to break the connection. In this case, they use "Po" as the first pronunciation of the child's name, such as "Pobai", "Poshe", and so on. They believe the lot of "Po" is hard enough to protect the child into old age. ~

The third circumstance occurs when a woman is giving birth and the umbilical cord hangs around child's neck or shoulders, which is considered a monstrous phenomenon. Consequently, the connection should be broken and the child's name should start with "Sha". "Shayao" and "Shabao" are two examples of this. The fourth reason the naming system is abandoned is when a child is born on the road. The child does not repeat his father's name and use "road" ("Ya" in the Jino language) instead. Also, if someone from other villages breaks the taboo and walks into the delivery room when the child is born, the connection is broken then. The child should acknowledge him as nominal father and repeat his name, so as to be protected by this outside power to grow up in good health.

Jino dance

Jino Love Customs and Gender Roles

Among the Jino, sons and daughters are equally desired. To have daughters is as valuable as having sons, though in some areas they think that daughters are better, and girls are educated in their traditions by grandmothers (Cheng 1993; Du 1991: 417). The husband is the head of the family and enjoys a higher position inside it. But the wife is not discriminated against and her role is higher in some social, productive, ritual and homely matters. [Source: “China’s last but one matriarchy: The Jino of Yunnan” by Pedro Ceinos Arcones, 2013 Ethnic China *]

The Jino address their relations according to generations, not sex. Grandson and granddaughters are all called lirao; sons and daughters, nephews and nieces all are called raozuo. Gender-free terms of address reflect that in the past people of the same generation could marry each other (Song 2007). Though the wife moves to her husband's house she is not separated from her own family, since people marry from inside the village. A piece of cloth symbolizes the equal position of women in the family. After divorce, women can take with them their property and their children.

Young Jino enjoy sexual freedom before marriage. There is no stigma attached to illegitimate children or to their mothers. In some villages, Jino build houses where the single young of both sexes spend the night. There are no discrimination against the children of unmarried mothers. Though spending the night together puts a couple on the way to marriage, they can separate if they want and choose a new lover. These relationship seems similar to the walking marriages among the Mosou, who enjoy complete freedom to choose their lovers. The main difference is that with the Jino after the period of free love young couples are supposed to—but don’t necessarily have to— marry, when the woman becomes part her husband’s family. *]

When boys reach the age of 14 or 15 years old they must pass through a ceremony of initiation called "wureha". Usually a group of boys comes of age together. When they finish, all the people of the village meet and, sacrificing a cow, welcome them to the world of the adults. Starting from that moment they are taught different aspects of the social, religious, economic and sexual life in such a way that when they finish it, they are considered adults. They are also considered able to fall in love, and they don’t have to spend the night at their parent’s house. *\

The Jino have various kinds of gatherings for young people. There is one where the boys gather called Raokao and another for the girls called Mikao. The young people get to know each other and fall in love in a long process of relations between the potential lovers. When they feel sure of their commitment, their parents fix their wedding. *\

Jino Marriage and Birth Customs

Jino marriages are monogamous. After marriage the wife lives in the husband's house. Jino cannot marry people of the same clan. In some villages there are very serious punishments for those who violate this taboo. On the other hand, when two people of the same clan fall in love but do not marry; their love is respected even beyond their death. Consanguineous marriages (marriage between people of the same blood) were common in the past (Cheng Ping 1993: 3).

In some Jino villages after the proposal of marriage to the bride's parents, “the young man must first go to live in the young woman’s home for one to three years of “trial” marriage. This “trial marriage” is a remnant of past matrilocality, when after marriage the husband moved to live in his wife’s home.

When the woman gives birth, she cannot eat the meat from chicken, pigs and big animals. Her husband leaves to hunt a squirrel. After squirrel is skinned and cleaned, a soup is made for the mother. This soup will have, according to their tradition, healthy effects on the newly born.

For important activities, such as building new houses and having parties in festivals, the uncle must be invited and esteemed as the guest of honor. If the uncle dies, the nephew and the niece should not wear earrings, wrap scarves or sing during the following year. The uncle, being highly respected, has the obligation to foster and protect his nephew and niece. When they get married, the uncle should give a lot of presents, even surpassing the amount given by their parents. If the parents of the nephew or the niece die when they are young, the uncle must take the responsibility of bringing them up. The responsible over nephews or nieces born out of wedlock also belongs to the uncle only. This custom was likely handed down from Jino’s former matriarchal society. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, kepu.net.cn ~]

Jino Wedding Process and Uncles

When young Jino man or woman decide to get married, they should first gain their uncle's approval. Especially during the process of the niece's wedding ceremony, the uncle occupies a pivotal position. After the niece is engaged, the bridegroom's father is expected to bring the matchmaker and present wine to the bride's family to enter a relationship with the uncle. Only then, can the marriage be said fixed. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

Two days before the wedding, there is a ceremony requesting the uncle to let the bride go. The bridegroom's father invites two witnesses of the wedding and many relatives and friends—taking with them five chickens, five bowls of nice wine, one package of diced meat as a ceremonial present, and some other presents—to the bride's uncle's home for a banquet and discuss about the details. During the feast, the matchmaker tells the wedding day plans to the uncle and explains that the uncle has the power of kinship over the niece. Only after getting the uncle's permission in this ceremony can the wedding be held as scheduled. For nephew to get married, though not as complicated as that of the niece's, he also has to offer presents to the uncle and get permission. ~

On the day of the wedding procession the groom's family goes to the bride's house to retrieve her. On the way to the groom's house her former lovers throw her dirty water, but when she arrives at the groom's house, his family throw her clean water. As soon as the bride arrives at the groom’s house there are some ceremonies carried out which fix her there. Her bone, however, remains with her uncle, meaning that she keeps an important link with her house, which is used in case of divorce. One of the main aims of the wedding ceremony is to carry the soul, spirit, energy and the meat of the bride to the bridegroom’s house, to accept that the name of her children will follow the name of her husband. (Du 2008: 181). [Source: “China’s last but one matriarchy: The Jino of Yunnan” by Pedro Ceinos Arcones, 2013 Ethnic China ]

Image Sources: Nolls China website; Twip.org and CNTO, Wiki Commons

Text Sources: 1) “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China”, edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company; 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China *\; 4) Chinatravel.com chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2022