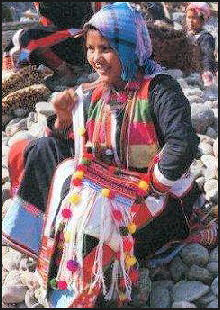

DE’ANG MINORITY

De'ang-Palaung woman in the early 1900s

The De’ang are very small minority that live primarily in mountainous and semi-mountainous areas and are descendants of people that have lived in the Yunnan for 2,000 years. The grow both wet and dry rice and have grown tea for centuries. Some have speculated that they may have been one of the first people to cultivate tea. The De’ang have lived in association with the Dai, Jingpo and Han. They are said to be descendants of the ancient Pu people. In the past the Dai were often their feudal lords. The De’ang speak a Mon-Khmer language, have no written language and practice Theravada Buddhism. [Source: Tan Leshan “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

Small in number but scattered over a large area, the De'angs live in China, mainly in Yunnan Province, and in Myanmar near the China border, mainly in the Shan State. Most De'ang in China inhabit Santai Township in Luxi County of the Dehong Dai-Jingpo Autonomous Prefecture and in Junnong Township in Zhenkang County of the Lincang Prefecture in Yunnan Province. The others live scattered in the Lincang and Pu'er Regions in Yingjiang, Ruili, Longchuan, Baoshan, Lianghe and Gengma counties. Some De'angs live together with the Jingpo, Han, Lisu and Va nationalities in the mountainous areas. And a small number of them have their homes in villages on flatland peopled by the Dais. [Source: China.org, Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences]

The De'angs practice Theravada Buddhism. Their life and religion are greatly influenced by the Dai people, who are Theravada Buddhists. The De'angs language that belongs to the Wa-Ang subgroup of the Mon-Khmer branch of the Austroasiatic language family. There are three local dialects: Bulei, Ruojin, and Rumai. The De’ang written language is not widely known and has been mainly used for the recording of their history, ethics, law and Buddhist works. Many De'ang speak the languages of the Dai, Han Chinese or Jingpo languages as they live among these people. Some can read and write in the Dai language. They started learning Chinese in increasing numbers in the years after the mid-20th century.

The De'ang people have been living there for generations in the mountainous areas of Gaoligong and Nushan ranges in western Yunnan Province, The climate here is subtropical, and there is fertile soil, abundant rainfall, rich mineral resources and dense forests. The dragon bamboo here grows very long and has a stem with a diameter of 10 to 13 centimeters. [Source: China.org]

Some regard the De’ang as being the same ethnic group as the Palaung who live mostly northern parts of Shan State in the Pa Laung Self-Administered Zone, with the capital at Namhsan. Some live in Northern Thailand. The Ta'ang (Palaung) State Liberation Army, the armed wing of the Palaung ethnic group, has the fought the Myanmar (Burma) military since 1963.

“Women Not to be Bound in Waistbands ; The Deangs” by Zhou Mingqi is a booklet put out in 1995 by the Yunnan Publicity Centre for Foreign Countries as part of the a “Women’s Culture series, which focuses on different ethnic groups found in Yunnan province. The soft-cover 100-page booklet contains both color photographs and text describing the life and customs of women. The series is published by the Yunnan Publishing House, 100 Shulin Street, Kunming 65001 China, and distributed by the China International Book Trading Corporation, 35 Chegongzhuang Xilu, Beijing 100044 China (P.O. Box 399, Beijing, China).

See Separate Article PALAUNG factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Women Not to be Bound in Waistbands: The Deangs (Women's Culture Series: Nationalities in Yunnan) by Zhou Mingqi and Hua Ergang Amazon.com; “Peoples of the Greater Mekong: the Ethnic Minorities” by Jim Goodman and Jaffee Yeow Fei Yee Amazon.com ; Xishuangbanna: the Tropics of Yunnan” by Jim Goodman Amazon.com;“The Yunnan Ethnic Groups and Their Cultures” by Yunnan University International Exchange Series Amazon.com; “The Dai or the Tai and Their Architecture and Customs in South China” by Zhu Liangwen Amazon.com; “Where the Dai people Live” by An Chunyang Amazon.com; “Educating Monks: Minority Buddhism on China’s Southwest Border” by Thomas A. Borchert and Mark Michael Rowe Amazon.com

De’ang Names and Population

The De’ang are also known as the Deang, Benglong, Bulei, Liang, Rumai, Ang, Benlong, Black Benlong, Liang, Niang and Red Benglong.. The De'angs living in Dehong call themselves "De'ang," but those in Zhenkang County and Gengma County and some others call themselves "Ni'ang" or "Na'ang." "Ang," which means "rock" or "cave". "De," "Ni" and "Na" are words added to show respect. Due to their different clothing and ornaments style the main De’ang tribes are sometimes called "Red De'ang," "Flowery De'ang," and "Black De'ang. [Source: Tan Leshan “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

The De'ang are the 45th largest ethnic group and the 44 largest minority out of 55 in China. They numbered 20,556 in 2010 and made up 0.0015 percent of the total population of China in 2010 according to the 2010 Chinese census. De'ang populations in China in the past: 17,935 in 2000 according to the 2000 Chinese census; 15,462 in 1990 according to the 1990 Chinese census. [Sources: People’s Republic of China censuses, Wikipedia]

Population growth in the past was relatively low as a high birthrate was offset by a high rate of infant mortality. Since the 1950s the population has been steadily increasing with the improvement of medical care and health conditions. The population of De'ang was estimated at about 6,000 in 1949 and had increased to 12,275 by the time of the national census in 1982. |~|

Early History of the De’ang

Where the De'ang live in western Yunnan

The De'ang are regarded as one of the most ancient nationalities in southwest Yunnan area. Considered ancestors are the ancient Pu people, they were called "Pu people" or "Mang people" in the Song dynasty. In the Yuan dynasty, they were named "Jinchi," and "Puren." In history books from the Qing dynasty, their name was "Benglong," which was applied after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. In September 1985, they were renamed "the De'ang nationality" by the Chinese government. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities]

The De'ang were given their name in the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). Before that time the De'angs along with the Blang and Va ethnic minorities speaking a south Asian language inside Yunnan Province were called "Pu people," according to historical records. In ancient times the "Pu people" were distributed mainly in the southwestern part of Yunnan Province, which was called Yongchang Prefecture in the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.-A.D. 220). Their forefathers settled on the banks of the Nujiang River (upper reaches of the Salween that flows across Burma) long before the arrival of the Achang and Jingpo ethnic minorities that live their now. [Source: China.org]

The ancient Pu were mentioned in the chronicles of the Chinese Qin Dynasty (221 B.C.) as the native population of the Western region of the present Yunnan Province. At that time the Chinese emperors did not have much influence in Yunnan. These Pu people are mentioned again in the books of history as one of the subdued peoples under the Nanzhao kingdom (A.D. 8th century ). What happened during long period is unknown. Modern descriptions of the De’ang way of life show that it was not influenced by the Nanzhao kingdom, nor by the Dali kingdom that followed it. [Source: Ethnic China]

De’ang Under the Dai and Tusi System

Development of De'ang society has been uneven. Since the De'angs have lived in widely scattered localities together with the Han, Dai, Jingpo, Va and other nationalities, who are at different stages of development, they have been influenced by these ethnic groups politically, economically and culturally. Dai influence is particularly strong since the De'angs had for a long period lived in servitude under Dai headmen in feudal times. However, some traces of the ancient clan and village commune of the De'ang ethnic minority are still to be found in the Zhenkang area. [Source: China.org |]

Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote in Ethnic China: “Their life did certainly change during the 15th century, when the Chinese Ming dynasty handed over the administration of De’ang lands to the Tusi (local chiefs who were used to govern the minorities in the emperors' name) of the Dai nationality. It was during this period that migration of Dai peasants towards De’ang lands began, forcing them further and further into the mountains and to much poorer land. The influence of Dai culture and the Theravadan Buddhist tradition that came with it, initiated a series of cultural and social transformations among the De’ang. However, the fundamentals of their economic life, including communal ownership of the land by extended families, remained unchanged until the nineteenth century, when increasing pressure by Han and Dai settlers brought about new changes. *\

“A handful of landlords, most of them Dai, held the majority of the land for themselves, creating a miserable situation for many De’ang families. In the winter of 1814, there was an uprising by the De’ang of Dehong against Tusi government oppression. The De’ang proclaimed, "the government is unfair, let's destroy the government and gain equality". Although they were ultimately defeated, the unchanged exploitation that was slowly turning De’ang peasants into landless laborers brought about a string of uprisings that continued throughout the 19th century. *\

“The Dai, through the tusi administrative structure, attempted to retain control over the De’ang. Decentralizing their power, they appointed some De’ang as village heads who would support their policies and collect taxes and contributions. The highest De’ang local official was the Dagang, who usually enforced the Tusi's policies over several villages. The Dajigang was the head of a single village. He was assisted by the Dapulong and the Dajige, who were in charge of different aspects of village administration, together with the Dajigang, who led the village. In some areas of Zhengkai and Genma Counties a type of local democracy was in effect. The Dagang was elected by the heads of the villages he administered, and the Dapulong and the Dajige were also elected by the people of their respective villages. *\

“The 20th century witnessed an increased presence of Chinese administration in De’ang lands, especially after 1956, when communist reforms began to be implemented. These reforms brought about a complete upheaval of De’ang traditional society, and a definitive loss of control over their lives and future. The Cultural Revolution and the wave of destruction that accompanied it, represented a direct attack against the De’ang way of life. In the current reform era the De’ang are today attempting to recover their culture and to find a ways of benefiting from the new society.” *\

See Separate Articles: DAI MINORITY AND THEIR HISTORY factsanddetails.com

Development of the De’ang Under the Communist Chinese

De'ang Palauan in the late 1800s

According to the Chinese government: “A new day dawned for the De'ang people when Yunnan Province was liberated in 1951. The first thing the De'angs did was to restore social order and develop farm production after helping the government round up remnant KMT troops who had turned bandits. In 1955 land was distributed to the De'ang people who made up half of the population on the flatland and in the semi-hilly areas of Zhenkang, Gengma, Baoshan and Dehong in an agrarian reform in which both the De'ang and Dai people participated. Not long afterwards, the De'angs set up agricultural cooperatives. At the same time, the rest of the De'ang people living in the mountainous areas of Dehong, like the Jingpos dwelling there, formed mutual aid groups to till the land, carried out democratic reforms and gradually embarked on the socialist road. [Source: China.org]

“The De'ang people, who lived in compact communities in Santaishan in Luxi County and Junnong in Zhenkang County, established two ethnic township governments. In July 1953, the Dehong Dai-Jingpo Autonomous Prefecture was established, and the De'angs had 12 representatives in the government. Many functionaries of the De'ang people are now serving in government offices at various levels. Some De'angs in Yunnan Province have been elected deputies to local people's congresses and the National People's Congress. |

“The economy in the De'ang areas has been developing apace. Take Santaishan in Luxi County for example. People here started farmland construction on a big scale with their Han and Jingpo neighbors in the wake of agricultural cooperation. Today, the land here is studded with reservoirs and crisscrossed by canals, and hill slopes have been transformed into terraced plots. Tea and fruit are grown, and large numbers of goats, cows and hogs are raised. The cropped area has increased enormously, and grain production is four times the 1951 level. |

“As the people of this minority group could scarcely make enough to keep body and soul together, no De'angs went to school in pre-liberation days. Those who could read some Dai words in those days were a few Buddhist monks. Pestilence and diseases due to poor living conditions were rampant, and there were no doctors. People had but to ask "gods" to cure them when falling sick. Today De'ang children can attend primary schools established in villages where the De'angs live. Priority is given to enrolling De'ang children in other local schools. Large numbers of illiterate adults have learned to read and write, and the De'ang people now have even their own college students, teachers and doctors. Smallpox which had a very high incidence in localities peopled by the De'ang people was eradicated with the assistance of medical teams dispatched by the government. Malaria, diarrhea and other tropical diseases have been put under control.” |

De’ang Religion

The De'ang are Theravada Buddhists. Most villages have a Buddhist temple, young men are expected to spend some time as monks and households are obligated to feed monks. The monks live on the offerings of their followers. Their daily needs are provided by the villagers in turn. People do not work during religious holidays or sacrificial days. The De'angs bury their dead in public cemeteries but those who die of long illness or difficult labor are cremated. [Source: China.org]

The De’ang have been followers of Theravada Buddhism since the Ming Dynasty, when they came under Dai rule. However, they have retained a number of the features of their indigenous religions. Both animist and Buddhist festivities are held. Sometimes, components from both traditions merge in important events, such as planting crops and funerals. There is a Buddhist temple in almost every village. These coexist as places of worship side by side with nature sites, such as large trees, the residing place of traditional De’ang deities. [Source: Ethnic China *]

Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote in Ethnic China: “According to one of their legends, Sakyamuni [The Buddha] and the Goddess of the Rice held a competition. Even though Sakyamuni won, he realized that, without the products of the land, which depended on the intervention of the Goddess of Rice, he would not get any offerings, so both deities reconciled. This might explain why in every person's heart both traditions coexist. Buddhism, used to solve the complex questions concerning human existence; and animism, used to ensure this very existence. *\

Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote in Ethnic China: “According to one of their legends, Sakyamuni [The Buddha] and the Goddess of the Rice held a competition. Even though Sakyamuni won, he realized that, without the products of the land, which depended on the intervention of the Goddess of Rice, he would not get any offerings, so both deities reconciled. This might explain why in every person's heart both traditions coexist. Buddhism, used to solve the complex questions concerning human existence; and animism, used to ensure this very existence. *\

“As well as the Goddess of the Rice, who is worshipped all year round, during every single harvesting period they worship another five gods in order to ensure good crops: 1) The God of the Land, who is in charge of ensuring the productivity of the land; 2) The Dragon God, who is in charge of the proper distribution of wind and rain; 3) The God of the Village, who looks after everyone; 4) The God of Heaven, who is responsible for the creation of the De’ang; and 5) The Snake God, who makes sure that reptiles do not harm people. *\

“According to De’ang traditional belief, if people are good, they are rewarded by going to heaven. If they are bad, they will go to hell. According to De’ang spiritual understanding, there is a world of yin and another of yang, corresponding to traditional Daoist thought. The first is the world of shadow and the second of light. When people die, they must travel from the world of light to the shadow world crossing, envisioned as a long river. This is why they bury their dead in boat-shaped coffins, which will help their souls to cross this river and arrive at the world of shadow. *\

“As for Buddhism, its influence has been unequal among the different De’ang branches. All them, however, do share some common characteristics: villages have a temple which is both a school and a place of worship; with monks who know how to read the Buddhist writings in Dai language acting as teachers. Novices study in the temples. Both monks and novices are fed by the villagers. *\

“But there are also some differences among the De’ang branches, or the three ethnic groups included under the name "De’ang", and we see that: 1) Among the Rumei ethnic group, the religious Buddhist schools are usually not very strict and there is harmony between Buddhism and the traditional religions. 2) Among the Bulei ethnic group, the Buddhist schools are very strict and many villages do not eat meat nor raise domestic animals. Many have given up their traditional celebrations and do not even drive away wild animals that enter their fields. 3) Among the Liang ethnic group, in some areas, like Zhengkai, the influence of Buddhism has been very superficial. In others, the most orthodox Buddhist schools have caused significant changes in their daily lives and culture. “ *\

De’ang Rice Goddess

The De’ang Goddess of the Rice is the most important of their traditional deities. She is honored several times a year in accordance with different steps of the agricultural cycle. Plowing is an activity that the men carry out, but before they begin, the women on the edge of the field sing aloud to the Goddess of the Rice: "Oh, goddess. Come to protect our field; don't let the deer and other animals tramp it." Only when they have finished their songs the men begin to plow the earth. [Source: Ethnic China *]

The sowing of seeds is carried out by women. Before they begin they carry out a solemn ceremony in honor of the Goddess of the Rice in which people meet in the field, children play cymbals and drums, a chicken and a pig are sacrificed, songs are sung asking the grain to grow well, and a ritual meal is eaten. By weeding time in each house a platform to honor the Goddess of the Rice. During a ceremonies held at this time the names of seven brothers and the seven sisters of the goddess are read out. That altar, located on the main wooden cross of the house, is object of ceremonies three times every month, directed by the family head.*\

Harvesting is usually carried out by women. During that time, offerings are continually made to the Goddess of the Rice. Sometimes the De’ang build a kind of house for her— a bamboo structure with white paper—called "The goddess's house". Before the harvest, during the ceremony of "Taste the new rice", De’ang take home the first rice that matures in the field, and they mix it with the old rice to make a ritual meal. Before eating it they offer it to the Goddess of the Rice, saying "Goddess of the Rice, taste our new rice." They also offer some rice to the ox and the dog, to thank them respectively for work the fields, and for protect them. Then they offer a part in the Buddhist temple, and in the end, the family finally has a chance to taste the new rice. *\

De’ang "Water-Splashing Festival"

Water splashing festival De’ang festivals are similar to those of the Dai. Many of them have some connection with Buddhism. Every year, they celebrate "Jinwa" (Close-the-Door, which means "Buddha going into the temple"), "Chuwa" (Open-the-Door, which means "Buddha coming out of the temple") and the Water-Splashing Festival, which is also a big event in Buddhist countries such as Thailand and Myanmar.

The Water-Splashing Festival of the De'ang people is usually celebrated in mid April and lasts three to five days. Marking the beginning of the new year, it is similar to water-splashing festivals held in Buddhist countries such as Thailand and Myanmar. Before the festival, people prepare new clothes, miba (a sort of food made of rice), a water dragon, and buckets and other containers for water. Buddhists gather in a temple to build a cottage and a water dragon that assists them in washing the dust off the temple’s Buddha statue. In the morning they march into the temple, listen to Buddhism sermons and sing prayers. Then, they build a pagoda with sand near the temple, and carry the statue into the cottage, which is built in the temple, and perform the ritual of washing it. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences]

The Buddhists pour the clearest water into the dragon. This water then flows from its mouth along a bamboo gullet and splashes all over the statue. Then, a respected old man dips a bunch of flowers into the water and then splashes the water to the crowd around. This is a blessing of the new year to everyone. Then, everyone gets excited and congratulates each other that a new year is coming. To the sound of songs and elephant-foot drums, young men raise buckets of water over their head and pour water onto the hands of the old, wishing them happiness and health. The old, then, try to hold the water with their hands, and say words of blessing to the young. Then, they line up in a long queue behind the elephant-foot drums and throng to waters beside the springs and rivers, celebrating the festival by singing, dancing, chasing and splashing water to each other. Water is regarded as a symbol of purity, good luck and blessing. Splashing water all around, everyone enjoys the festival.

The Water Splashing Festival is not only a festival that celebrates the New Year, but also provides a good opportunity for young men and women to court one another. Unlike the Dai who "throw bags" when courting, the De'angs have a custom of presenting bamboo baskets, which is often performed by a young man who has found a lover. The young man often makes several baskets before the festival, and presents them to the girls he likes. To the girls he likes the most he gives the prettiest basket that he has woven to show his love, and to see her response. A girl may receive several baskets. If she likes a particular boy she carries it on Water-splashing Day. On Water-splashing Day the boys looking around to see if any girls at all the baskets very carefully to see whether the girl is carrying their baskets. When he discovers his own, he splashes water on the girl, which is returned happily with full joy.

De’ang Love and Courting Customs

Young people have the freedom to choose their own partners, and courtship lasts for a long time. When a girl hears a love song under her window, she either ignores it or responds. If she likes the boy singer, she tosses a small blanket down to him. Then she opens the door and lets him in. The boy covers his face with the blanket, enters her room, and meets the girl by the side of the fire. The parents are happy and do not interfere. The lovers often meet and chat until midnight or dawn. After a few dates, the boy gives her a necklace or waistband as a token of his love. The more waistbands a girl gets, the more honored she is. To show his devotion, the boy wears earrings. The number she gives him is a mark of her love. [Source: China.org]

Pedro Ceinos Arcones wrote in Ethnic China: “In all stages of courtship and marriage, music plays a dominant role, as does tea. As they usually live in two-story houses in which people sleep upstairs and the animals downstairs, the suitor normally approaches his loved one at night, singing to her beneath the window. Once he awakens her, if she likes him she invites him to come in and they spend the night singing together while they drink tea. The rest of the family act as if they have not heard anything and sometimes even help their daughter reply to the duets that the suitor initiates. [Source: Ethnic China] *]

“If love develops, the young man will give her a tea sachet that she will hang next to her bed. Once her parents see it, they understand that their daughter has a suitor and then wait for the matchmaker to arrive. Symbolically, the matchmaker also brings a tea sachet with her to begin the talks that will result in a wedding. As a general rule, a significant dowry is not demanded by the bride's parents, so everything goes smoothly. On the wedding day, the bridegroom's family arranges a wedding party, during which people sing and dance throughout the night. At this time the bride pays her respects to the elders of her new family. *\

See Water-Splashing Festival Above

De’ang Marriage Customs

Among the De’ang, monogamy is practiced. People of the same clan do not marry with one another. This means marriage between a man and a woman is not allowed if the couple has the same family name. Frequently, sexual relationship takes place before marriage. If a child is born, there is no discrimination against the child, who becomes part of the husband's family the day they get married. Divorce is not a big problem. If the husband asks for I he simply offers a gift to the village's chief on behalf of the gods. If it is the wife wants a divorce, she need only return all the presents she received at the wedding. Intermarriage is rare with people of other ethnic groups.

If the courtship goes well, the boy would offer gifts to the girl's family and send people to propose marriage. Even if the girl's parents disagree, the girl can decide for herself and go to live in the boy's house. A De'ang wedding party is gay and interesting. Each guest is sent two packages, one containing tea and the other cigarettes. This is an invitation. They bring gifts and firecrackers to the bride and groom. The new couple first enter the kitchen and put some money in a wooden rice tub. This means they have been nurtured by the cereal, and now show their gratitude. [Source: China.org]

Water-drum dancing is an important part of the wedding ceremony. The drums are made of hollowed trunks into which water is poured to wet the skin and center to determine its tone. Water-drum dancing has a legend behind it. In ancient times a young De'ang man's beautiful fiancee was snatched away by a crab monster. He fought the crab, vanquished it, ate it, and made a drum of its shell. At today's wedding ceremonies, water-drum dancing symbolizes true love.

De'ang Funerals and Taboos

1) No living things can be killed during the three months between the Close-door Festival (September15th of the Dai ethnic group calendar, also June 15th of the Chinese lunar calendar) and the Open-door Festival (December 17th of the Dai calendar, also September 15th of the Chinese lunar Calendar). 2) De'ang people worship snakes. People usually regard a big tree near the village the "snake tree" and build fences around it. They offer sacrifice to the tree once a year. It is not allowed to cut down the "snake tree", nor can people walk near to the tree. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

3) De'ang people view one of the big trees around or near the village as the place where the village deity lives. They sacrifice the tree during the Spring Festival every year. It is not allowed to cut down the sacred tree, nor can people relieve themselves near the tree. 4) There is a piece of pointed wood placed on a sand pile in the center of the village. The wood is the symbol of the deity of the village, called Zaowuman in De'ang language. Zaowuman is the guardian angel of the whole village. It is not allowed to touch the tree or relieve oneself near the tree. 5) De'ang people present two jars of clean water before the deity of "shemeng" in a bamboo house with couch grass roof in the forest near the village. Strangers are not allowed to enter the house. \=/

De'ang people bury the dead in the ground. There is a public graveyard in the village. When villagers die, they are buried in same matter whether they are rich or poor. The De'ang don't build graves, nor do they put up tablets for the dead. Families of the dead invite Buddhist monks to recite scripture to console the soul of the deceased person seven days after dead. De'ang people do not identify their family's burial place, nor do they put wreaths there. \=/

There is an old story about how the De’ang basic funeral customs were formed. A long time ago, there was a tribal chief named La You in a De'ang village. His wife, Ha Mu, gave birth to a son at the age 40. The boy was named A Tuo. Unfortunately, A Tuo died of malaria at 10. The heartbroken couple asked a carpenter to build a big house in the mountain and placed A Tuo's body there. For three years, their servants sent their dead son three meals a day. One day, when the servant was on his way to the big house, a heavy rain and the flood stuck him. Then three monks passed by. The servant offered the meals to them respectfully. That night, La You and his wife had the same dream. In their dreams their son told them that he hadn't received any meals sent by them until that night. The astonished couple asked the servant whom he had given the meal to. The servant told them what had happened. Then they realized that it was useless to sacrifice meals to the dead. From then on, De'ang people didn't identify their relatives' graves after their death. They didn't put wreaths there. And they only worship Buddha. \=/

De'ang Houses and Village Life

Palaung village

A De'ang village is usually composed of several groups in which the lines of descent are from male to male. Each group is composed of several to thirty or forty nuclear families with a patriarchal authority structure and patrilineal (male to male) inheritance. Labor is divided by age and sex, with men doing the heavy work, women tending the fields and the elderly doing weaving and household chores. Marriages are usually between members of different patrilineal groups within the same village, with a man marrying the daughter of his mother’s brother being the preferred union.

Like many people in the southern regions of China, the De'angs live in bamboo houses with railings. The framework of the house is made of wood, but all the other parts, such as the rafters, floor, balcony, walls, doors and stairs are made of bamboo. The the roof is often thatched. Most bamboo houses face east and back against a hill. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

There are two main types of De’ang houses: square ones and rectangular ones. A typical two-story bamboo house in the Dehong area is square and has a yard and two subsidiary cottages. People live in the upper floor, in which there is a living room, bedrooms and rooms for storing grains and sundries. The lower floor is used for raising the stock. The subsidiary cottage, leaning on the main house, is built for storing firewood and foot-pedaled mortar and pestles used in husking rice. The shape of the bamboo house is beautiful in shape and graceful in taste. It looks like a Confucius student's hat, which was popular in the Central Plains in ancient times. ~

There is a story about how these houses evolved. In the Three Kingdoms period, the Shu Kingdom general Zhu Geliang, led his army to pacify an uprising in the south. When he arrived in a De'ang village, he was attacked and hurt. Fortunately for him, a brave and kind-hearted De'ang girl named Anho, saved him. The two fell in love. However, Zhu Geliang had to leave because his army was called home. Before he departed he promised Anho he would return. The girl was deeply in love with him and waited for 18 years, only to hear the sad news that her beloved was dead. From then on, the brokenhearted Anho neither ate or slept, but only stood on the east side of the village and looked off in the distance in the direction he departed. This lasted for 33 days. Then one day there was great thunder and lightning and Anho disappeared. At the place where she had stood, a house appeared, which was exactly in the shape of Zhu Geliang's hat. And that is how the De'angs bamboo house came into being. ~

De'ang Food

Rice followed by corn, wheat and potato are the De’ang staple foods. They steam or stew their food and are very fond of sour, pickled and hot food . Their snacks include tofu, rice noodles, rice cake and Tangyuan (a kind of stuffed dumplings made of glutinous rice flour served in soup), etc. They grow many vegetables and gather bamboo shoots, which they don’t eat fresh, but make it into pickles and dry it for future use. De'ang like to add pickled bamboo shoots into their stewed food, fryied meat and cooked fish. Influenced by the Han, they also eat Han-style pickles and preserved bean curd. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

Braised vegetable pickles is very popular. To make it: 1) wash leafy green vegetables, 2) cook them in the pot, and 3) add some pickled bamboo shoots, meat, cooking oil or some fermented soy beans. The cooked food tastes a little sour first and then a little sweet. 4) Then they squeeze the vegetable pickles. De’ang mix the sour liquid together with some chilies and use it as their own vinegar, Pickled Padong vegetable is also called Jizhua (meaning chicken claw) vegetable. People pick the tender sprout of the Padong tree, dry them in the sun for a while to remove the water. Then they wash the sprouts, dry them, and pickle them before sealing the pickles in an earthen pot. Finally they put the pot near the fire pit and roast the pot by the fire for three days to make the pickles. \=/

To make pickled leafy vegetables: 1) radish leaves are sealed in a container until the green leaves turn yellow. 2) Take out the vegetables and wash them. 3) Dry them in the sun to remove the water. 4) Chop up the vegetables and put them in an earthen pot and seal them. 5) Put the pot upside down for about ten days. 6) Take out the vegetables then and cook them for a short while in a cooking pot, then dry them for storage.

Tea and the De'ang

The De'angs like drinking strong tea their sour and hot food. They have a reputation for growing top-quality tea and may be the oldest group of people in the world to continually grow tea. Nearly every family grows tea around their houses or on the margin of their villages. The De'ang have long enjoyed the fame of "old tea farmers." Anong ancient ruins in Yingjiang and Luxi counties of Dehong Prefecture, there are some old tea trees, which are about two or three hundred years old, with one third of meter in diameter. People say the ancient De'ang people left behind these old

One of their myths describes how tea leaves fell from heaven in order to give rise to mankind on earth. One old De'ang verse goes:

Tea is the life of the De'angs.

And where there are De'angs, there is tea.

So long as down this ancient song passes,

So long the fragrance of tea lasts.

This is an ancient song of the De'ang people.

Tea is an indispensable part of De'ang life. Strong tea is especially favored. When they make tea, the De’ang often put a lot of tea leaves into a jar, and boil them with a small amount of water until the water turns into deep coffee color. The tea is then poured into a mug for drinking. This kind of tea is so strong that non-De’ang who drink it have a hard time falling asleep after drinking it. The De'angs by contrast are so addicted to tea after years of drinking it all the time, they feel uncomfortable and weak without it. After a hard day’s work, they feel quite refreshed drinking a mug of strong tea. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities]

Tea is not only an important drink, it helps keep De'ang society running smoothly and is the centerpiece of De’ang etiquette. Among the De'angs, tea carries their good wishes and welcome. When a guest arrives, the host first serves him or her a cup of tea. A visit to friends, relatives, or the matchmaker, also requires tea. To invite friends and relatives, a small package of tea tied with two pieces of red crossing threads is customary. One who has injured another in a misunderstanding and wishes to apologize brings tea to the injured person as a gift. De'ang people use tea as the gift when they propose marriage. When they host a dinner, they use tea as the "invitation card". If they want the tribal headman to mediate the dispute between them and the other people, they always wrap a roll of tea and a roll of tobacco and present them to the headman before they male their case.

Importance of Tea in De’ang Culture and Life

De’ang consider themselves descendants of tea. In his book “Identity, Relationship and Difference: The social life of tea in a group of Mon-Khmer speaking people along the China-Burma border,” Li Quanmin investigates the relation between the the Ang, a De’ang subgroup, and tea. In the book Li discusses how tea growing molds the Ang way of life and production, how it influences its religious customs, how it is integrated in their social and family life and ironically how refuse to cash in on Han Chinese “tea-worship” even though they are believed to be among the world’s oldest tea growers, producing it for over on thousand years. [Source: Li Quanmin, “Identity, Relationship and Difference: The social life of tea in a group of Mon-Khmer speaking people along the China-Burma border,” Yunnan University Press. 201; Ethnic China *]

In the preface to the book Australian anthropologist Nicholas Tapp wrote: “It shows quite clearly that, although tea has been traded through petty markets for centuries, so that the Ang were never an isolated or segregated community, the importance of tea for them goes beyond its economic or commercial value. Tea is a marker of their very identity… Tea forms the most important part of virtually every social and ritual exchange...The reciprocity of tea exchanges and offerings within the community knits Ang society tightly together. Tea is used at marriage exchanges and at Buddhist monastic and merit-making rituals… Exchanges of tea punctuate the life-cycle at birth, courtship, marriage, the establishment of a new house, and death. It is all at once a “food, herb, beverage, and good”. The book provides a detailed examination of the use of tea during all these occasions, from family rituals to temple festivals, and shows how it functions as a primary “symbol of wealth” for the Ang...Tea… links Ang insiders together through gifts and exchange, and also connects them to the outside through market trading. It establishes relations with supernatural beings and outsiders as well as cement pre-existing ones.” *\

Li Quanmin himself wrote: “The Ang use their production, exchange and consumption of tea to express their identity and make important statements about their relationships with themselves and others... The discussion focuses on two issues: how the Ang make use of ideas about and exchanges of tea to convey particular ideas about their identity and represent their social relationships, and how Ang use such representations to maintain a sense of their own identity despite the important influences of Tai-ization and now Sinicization in contemporary Chinese society.” *\

De'ang Clothes

De’ang men and women wear long sarongs. Women have traditionally shaved off all their hair and covered their head with a black turban decorated with velvet balls worn above cylindrical silver earnings. Many girls no longer shave their heads or wear turbans.

De’ang traditional costumes are studded with silver ornaments. Even males wear them. Boys look handsome with their silver necklaces. Most women wear dark dresses lined with extra large silver buttons at the front, and skirts with red and black flower patterns. Rattan waistbands and silver earrings add grace and harm. Nowadays, De'ang boys have the same hairstyle as the Hans and do not like to burden their bodies with heavy ornaments. Men have the custom of tattooing their bodies with designs of tiger, deer, bird and flower. [Source: China.org]

De'ang men usually wear indigo or black robes buttoned on the right together with short broad trousers. They wrap their heads with black or white scarves decorated with colored pile beads on two sides. Women often wear black or dark blue blouses together with long skirts, black head wrappings, and coats laced with two pieces of red cloth and embroidered with colorful strips. The buttons of such a coat are four or five big square silver pieces. Young men and women like wearing silver necklaces, Ertong (a sort of ornament worn on the ear) and earrings. Due to their different clothing and ornaments style the main De’ang tribes are sometimes called "Red De'ang," "Flowery De'ang," and "Black De'ang." [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

Of all the clothing and accessories of De'ang people, women's girdles are the most beautiful and conspicuous. According to their custom, a grown woman wears several, or even dozens of girdles, which are often made of rattan or screwy silver threads. Rattans used for making girdles are of different sizes, and often painted red, black or green. Some are even carved with patterns or coated with silver. This unique custom can be dated back to their ancestors in the Tang dynasty, who had the custom known as "rattan girdle around the waist." ~

Legend has it that the ancestors of the De'ang people came from a gourd. When they were just out, men and women were the same, and girls used to dance all over the sky. Later, the god gave men wisdom and thus distinguished their countenance from that of women. In order to tie the women down to the ground, men had to make rattan hoops and loop them over the girls' waists. The girls could not fly anymore and had to live with men, and the hoops gradually developed into today's girdles. It is said that the more girdles a girl wears, the more elegant they are, and the more intelligent and capable the girl is proved to be. So, women often wear a lot of girdles, and regard this as an honor. Trying to win their sweethearts' favor, young men often present the girls with elegant girdles engraved with a lot of animal or plant patterns as a love token. ~

As a special ornament, De'ang also wear small colorful balls made of fine cloth. They are often attached to the two ends of men's head wrappings, or in front of their chest, on the lap of women's clothes, or on their necklaces. Often young people wear the balls on their earrings and handbags. In the past, the De'ang tattooed their bodies, usually the legs, arms and chests with patterns of tigers, deer, horses, plants such as flowers and grass, and scriptures or incantations in the Dai language.

De'ang Crafts and Myths

The De’ang are skillful in making bamboo utensils and thatching (making couch grass into material for house covers). Silversmith craft is also a traditional business of the De'angs, and is known among the neighboring nationalities. The De’ang also have a magnificent body of oral literature. Among their myths, "The ancestors create the world" is their creation myth. It describes how Potare, the creator, guides the creation of the world and mankind. There are several versions of the flood myth, most have the ancestors of the De’ang surviving the disastrous flooding by seeking refuge inside a or gourd that floated on the surface of the water until the earth became dry. [Source: Ethnic China *]

There are a number of Deang folk tales, such as "The frog and the embroiderer", "Two friends", "Three Strange Things" and "The Death of the Rat". Among the myths often sung are: 1) "One hundred leaves and one hundred people", about human beings were created from tea leafs; 2) "Histories of the flood", narrates the story of the flood that covered the world, and the way some human beings survived; 3) "The origin of the De’ang's branches" relates how, in remote times, a dragon lady bore three children from a bird husband. These three sons are the ancestors of the Red De’ang, the Black De’ang and the Flowery De’ang. *\

De'ang Music and Dance

De'ang people are good at singing and dancing. Whenever they celebrate a festival, hold a wedding party or build a house, they invite folk singer to sing poems. De’ang love songs are almost too numerous to count. Every step of the courting process is accompanied by songs sung by both the girl and the boy. Among the most beautiful and moving is "Sad Song of the Lusheng" that tells of a tragic love story frustrated by the girl's parents. According to tradition, after this unfortunate event, young De’ang women won their freedom to choose their partners.

Among the De’ang musical instruments are: 1) different types of flutes; 2) drums made from elephant's feet (similar to that of the Dai); 3) wooden drums; 4) the sanxian, a stringed instruments with three strings and 5) the sixian, a stringed instrument with four strings. One unique De'ang musical instrument is the "water drum", which is called "gelengdang" in the local language. The water drum is made by hollowing out a piece of round wood, which is 30 centimeters in diameter and 70 centimeters in length and covering the two ends with cow skin. People put some water into the drum before they use it. During the important festivals, a leading dancer hangs the water drum in front of his chest breast. He dances while beating the bigger drum end with a drum hammer held in his right hand and the smaller drum end with his left hand. People follow his steps, form a circle and dance happily.

De'ang people also do a lot of folk dances. In the drum dance, De'ang people play drums or small cymbals whenever they dance. The Gayang dance is the dance of Yang people who live Longchuan County in Dehong Prefecture and Mengxiu County in Ruili Prefecture. The Circle dance is dance is popular in Zhenkang County in Lincang Prefecture usually performed by men. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

The Bamboo pole dance is a funeral dance, played only at the funeral ceremony of old people who died at the age of 70 or above. The dancers wear clusters of bells around their waists. They beat the ground with four thin and two thick bamboo poles and dance. The bamboo poles are a symbol of horse, and the sound of the beating is a symbol of galloping. They dance three times a day (in the morning, at noon and in the evening) over the three days while people keep vigil beside the coffin. The dance is both to extol the dead person's merits and help the soul of the deceased to go to the heaven easily (by riding the "horse"). \=/

De'ang Agriculture

The De'angs have been farmers since very ancient times. They grow both wet and upland rice, corn, buckwheat and tuber crops as well as walnut and jute. After the founding of the People's Republic in 1949, they have learned to cultivate cotton, coffee, and rubber. The are producers of tea. In the De’ang areas dragon bamboo grows very long and has a stem with a diameter of 10 to 13 centimeters. The Zhenkang area has been famed for this kind of bamboo for the past 2,000 years. It is used to build houses and make household utensils and farm implements. Bamboo shoots are a famed delicacy.

The De'angs have been great tea drinkers since very early times. Every family has tea bushes growing among vegetables, banana, mango, jack fruit, papaya, pear and pomegranate trees in a garden around the house.

Being Buddhists, the De'angs in some localities do not kill living creatures. This has its minus side — wild boars that come to devour their crops are left unmolested. This at times results in quite serious crop losses. Formerly the De'angs did not raise pigs or chickens. A rooster was kept in each village to herald the break of day. Today this old custom has died, and chickens are raised. [Source: China.org |]

Image Sources: Nolls China website,

Text Sources: 1) “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China”, edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company; 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China *\; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2022