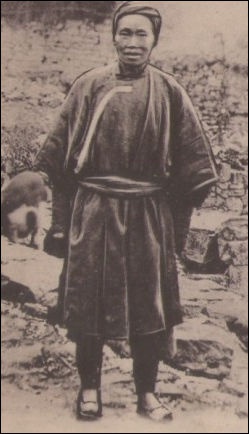

BOUYEI IN THE 1900s

Samuel R. Clarke wrote in “Among the Tribes of South-west China”: “Of all the non-Chinese people found in China proper we think those people who in Guizhou are called the Bouyei are the most numerous, and, for some reasons, perhaps the most interesting. There are probably six or seven millions of them in the four Chinese provinces of Yunnan, Guizhou, Guangxi, and Guangdong, and twice as many more in the adjoining states of Burma, Northern Vietnam, and Siam. In Burma they are called the Shans or Shan tribes. On the southern border of the Chinese Empire they are called the Laos or Lao tribes, and in Northern Vietnam and Siam (Thailand) they are called the Tai or Tai tribes. In fact, there seems to be no end to the names by which the various divisions of this race are designated. Who are they? [Source: “Among the Tribes of South-west China” by Samuel R. Clarke (China Inland Mission, 1911). Clarke served as a missionary in China for 33 years, 20 of those in Guizhou]

They have no written language of their own, but like the Miao do all their writing in Chinese. They have many simple love ditties which the young men and maidens sing to each other, and herein they are more like the Miao than the Chinese. We have seen some of these ditties written down in Chinese characters. Sometimes the character represents the sound of the Bouyei word with more or less accuracy, and sometimes the meaning, which makes it very difficult for one who does not know the ditties to decipher.

Although called by different names in various parts of the province, they are not divided into tribes like the Miao. About Anshun they are divided into two sorts: the Pu-la-tsz, who are dwellers in the plain: and the Pu-lung-tsi', who take their name from a powerful chief of former times named Lung. Their dialect varies in different parts, but not so much as to make them unintelligible to one another, as is the case among the Miao. We once had a servant, for two or three years, whom we took to be a Guangxi Chinese, but talking to him one day about his native dialect, we found he was of the same race as the Bouyei and could understand their speech. [Source: “Among the Tribes of South-west China” by Samuel R. Clarke (China Inland Mission, 1911)]

We have not been able thus far to discover among them any old legends handed down from former times. If they ever possessed such legends, their wish to be thought Chinese, and the claim that their ancestors were Chinese from Guangxi, is a potential reason why such legends should be neglected, and in course of time forgotten. Possibly elsewhere others may be more successful in the search for legends than we have been.

See Separate Articles: BOUYEI MINORITY: HISTORY, RELIGION AND FESTIVALS factsanddetails.com ; BOUYEI LIFE AND CULTURE factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Bouyei of China” Amazon.com; “Leaves and Songs as Matchmakers: The Buyis” by Ma Hexuan Amazon.com; “The Bouyei Language” by Will Snyder Amazon.com; “Bouyei-English Lexicon” by Thomas J. Hudak Amazon.com; “The Roots of Asian Weaving: The He Haiyan collection of textiles and looms from Southwest China” by Eric Boudot and Chris Buckley Amazon.com; “Writing with Thread Traditional Textiles of Southwest Chinese Minorities” by University of Hawaii Art Gallery Amazon.com; “Guizhou Batik” by Wan Zhixian and Ma Zhenggrong Amazon.com; “The Art of Silver Jewellery: From the Minorities of China, The Golden Triangle, Mongolia and Tibet” by René Van Der Star Amazon.com; “Amid the Clouds and Mist: China’s Colonization of Guizhou, 1200–1700" (Harvard East Asian Monographs) by John E. Herman Amazon.com; “Empire and Identity in Guizhou: Local Resistance to Qing Expansion” by Jodi L. Weinstein Amazon.com; “Narrating Southern Chinese Minority Nationalities: Politics, Disciplines, and Public History” by Guo Wu Amazon.com

Where the Bouyei Lived in the 1900s

Samuel R. Clarke wrote in “Among the Tribes of South-west China”: “The term Chung-chia [the name used for the Bouyei in the 1900s] is Chinese. Chung possibly means the second of three brothers: Chia, as we have already explained, means “Family “ or “Tribe," and the term may be used to convey the idea that they are inferior to the Chinese and superior to the Miao. Another explanation is that Bouyei means heavy armour, and refers to the sort of armour used by them in ancient times. But etymological explanations are not always satisfactory, especially in Chinese, where so many words of vastly different meaning have the same, or very nearly the same, sound. Around Guiyang and, we believe, elsewhere in the province they call themselves Bu yuei. Bu is a personal prefix, but what yuei means we are not able to say.[Source: “Among the Tribes of South-west China” by Samuel R. Clarke (China Inland Mission, 1911)]

As we have mentioned elsewhere, the Chinese are most numerous in the cities and near the great high-roads of the province, and the various tribes-people in more out-of-the-way districts. Within ten miles of Guiyang, the provincial capital, are some of the Miao, and probably two hundred villages and hamlets of the Bouyei, some of them containing as many as two hundred families. Ten years ago Mr. Edgar Betts travelled across country from Tushan to Singyifu, a journey of seven days, nearly two hundred miles as the crow flies, through a region entirely occupied by the Bouyei. There were no high-roads and no inns: the people for the most part were well-to-do, and readily offered him hospitality at the end of each day's journey.

It is said that the inhabitants of Tushan city are mostly Bouyei, or ShuYi, as they are called there, and many of them admit that this is so. Some of them engage in trade and settle in Chinese cities and towns, and if they remain there, as many of them do, they bind the feet of their girls and are reckoned as Chinese. The Chinese do not despise the Bouyei as they do the Miao. Miao rebellions and uprisings are not infrequent, but we never heard of a Bouyei rebellion. We know a Bouyei man, living near Guiyang, who nearly fifty years ago, when only eight years old, was carried off by a party of Miao rebels and taken to Hwangchow among the Heh Miao. He stayed with them till he was eighteen and then ran away home. He told me they did not treat him unkindly.

Bouyei and Chinese in the 1900s

Samuel R. Clarke wrote: “Wherever the Bouyei are found in Guizhou, and we believe also in some parts of Guangxi, they invariably assert that their ancestors were Chinese who came from the province of Guangxi, and many of them name the prefecture and county from which their forefathers came. But it must be borne in mind that these people speak a language which is not a dialect of the Chinese, but resembles the speech of the Shans and Siamese, and, for the identification of scattered tribes, there is no more trustworthy guide than a comparison of vocabularies. Most of the men, however, and some of the women can also speak Chinese. It may interest, and possibly encourage, students of Chinese to know that many of the Bouyei in speaking Chinese leave out all the aspirates: and yet the Chinese seem to understand them! We have heard them say, and we think the statement is true, that out of every three words they utter when speaking their own language, one is Chinese. [Source: “Among the Tribes of South-west China” by Samuel R. Clarke (China Inland Mission, 1911)]

But how does it happen that these people, who speak another tongue, claim to be Chinese when they are not, or for the most part are not, Chinese? This, we think, is not very difficult to explain. When they entered Guizhou the Miao were there before them. They probably looked down on the Miao then, as they do now, especially as the Heh Miao, who are in almost every way their equals, had at that time not reached those parts. Before the Chinese really occupied the province and systematically colonised it, there had been frequent wars and military demonstrations against the turbulent Miao. There were also on these occasions garrisons left in different parts of the country. Some of these soldiers took native women as wives, and formed separate communities, and are now called the “ Old Chinese." Others of them, or the children of these garrison soldiers, married into Bouyei families. This marrying into Bouyei families probably went on for a long period, so that in course of time many of them were really descended from the Chinese, and others were related to them by marriage. If any man traces his own ancestry back, say for half a dozen generations, he reaches a point of time when he has a large and varied assortment of ancestors, among whom he may select his extraction. This is emphatically true of Guizhou, where most of the Bouyei now in the province have more or less Chinese blood in their veins. As the Chinese are the superior and ruling race, it is natural that as many as can claim to be related to them should do so, and this they are the more likely to do so as not to be regarded as Miao.

When two or three hundred years ago Chinese immigrants from Guangxi entered the province in large numbers, and more men than women, doubtless many more of them married into Bouyei families. The relations already existing between the Bouyei and the earlier settlers would make it more easy and natural for the later settlers to ally themselves with Bouyei families. It is to be noted that the Chinese words which the Bouyei have adopted into their own language are not pronounced as the Chinese now around them — who are mostly from Sichuan and Hunan — pronounce them, but as they are pronounced in Guangxi and the lower regions of the Yangtze River.

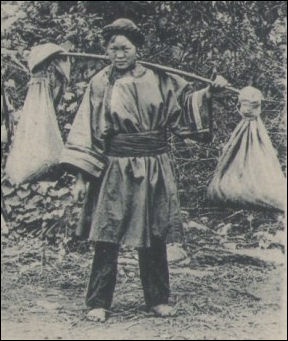

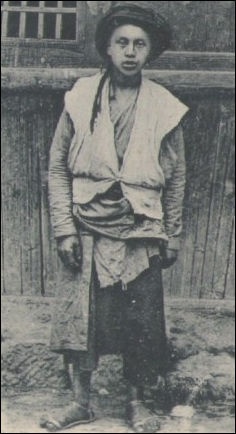

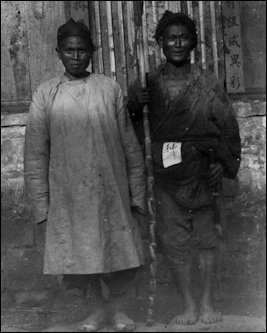

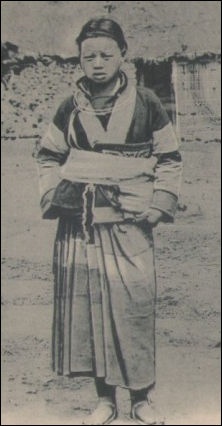

The Bouyei men can hardly be distinguished from the Chinese. Perhaps their noses are more flat and their eyebrows more bushy than among the typical Chinese, and the same may be said of the women. As most of them are farmers, the men dress exactly the same as Chinese farmers and village folk. On special occasions, like the Chinese countrypeople, they wear the jacket and long robe. Many of them compete at the civil and military examinations, and some of them have risen to high rank in the Imperial Service. The late Chen Kung-pao, Viceroy of Yunnan and Guizhou, was of this race.

Like the women among the Miao, the Bouyei women do not bind their feet. Their old tribal or native costume is a rather tight-fitting jacket, and a skirt very like the skirt worn by Miao women, but longer than some of the Miao skirts. This costume is still common in some parts, but around Guiyang the Chinese fashion for women of wearing loose jacket and trousers is evidently taking the place of the old style, especially among the younger women. Owing to their natural and more useful feet, they do more work in the fields than Chinese women. We cannot remember ever to have seen a Chinese woman planting rice in a paddy field, but we have often seen Miao and Bouyei women going into the field alongside of the men and planting rice.

Bouyei Religion in the 1900s

Clarke wrote: “As they claim to be Chinese, they do, or profess to do, as the Chinese do in religious matters; but they are certainly not so moral or so religious as the Chinese. Many of them have in their homes the same Heaven and Earth Tablet of five characters as the Chinese. There are sometimes little shrines just outside their villages, in which may be images or simply stones to represent local deities; but they do not build temples in their villages as the Chinese do, nor do they, as a rule, invite Buddhist priests. [Source: “Among the Tribes of South-west China” by Samuel R. Clarke (China Inland Mission, 1911)]

They are, we think, more Taoist than Buddhist, but they have notions and practices which are neither Taoist nor Buddhist. Some of them about Anshun seem to believe in two deities, a Good and an Evil one. The Good Being they call Tni-hsien, and say he lives in heaven, that he sends the rain and sunshine, and all good things come from him. This is all they know about him, and they neither offer sacrifices to him nor worship him. On the other hand, they are very much afraid of the Evil Being, and do all they know, or think they know, to appease him, by offerings and ceremonies which are generally performed in front of what they call “Spirit trees,'' that is, trees which from their great age, or for some other reason, are supposed to be intelligent and to have some sort of spiritual influence.

We have said that the Bouyei are more Taoists than Buddhists, and for this reason, Taoism, at the present time in China, is chiefly concerned with demons and malicious spiritual influences. Many of the Chinese, when there is sickness or misfortune in the family, or when their luck is bad, put it down to evil spirits and send for a Taoist priest, who by incantations, charms, and other performances drives away the pestilent demons, and counteracts their evil influences. In the same circumstances, Miao, Bouyei, and Nuosu send for their local wizards or exorcists, who profess to be able to deliver them from these persecuting demons in much the same way. Animism is, we think, the ancient and indigenous religion of the Chinese, as it is the religion of all the nonChinese races of Guizhou. For all of them the spirit world is not far off, and is peopled by unseen intelligences whose constant interference in human affairs is not to the advantage of those concerned.

Bouyei Burial Customs in the 1900s

Clarke wrote: The burial customs of the Bouyei about Guiyang are much the same as among the Chinese, but some of their sacrifices to the dead are not the same. The following is a description of the sacrifice of a bull, on behalf of a man recently dead, witnessed by my wife at Suei-ngan-pa, about five miles from Guiyang: "In the yard of one of the houses a number of people had assembled. Most of the men wore a strip of white calico across the middle of the cap. A procession was formed and they all moved out of the yard. First came a man like a Taoist priest, accompanied by the chief mourner dressed in white, with a stick in his hand, inside of which there was said to be silver. This chief mourner walked bending forward and pointing the stick towards the ground. Next came a young red bull led by a new straw rope. Then followed a riderless horse with the dead man's cap fastened on the saddle: there were also a fan, a spectacle case, a pair of boots, and a bottle of whisky hanging from the sides of the saddle. [Source: “Among the Tribes of South-west China” by Samuel R. Clarke (China Inland Mission, 1911)]

''Following these came about eight women with white jackets and long white hoods, the back of some of the hoods almost reaching to the ground. They all had shoes and stockings such as men wear, and pleated skirts of green, blue, black, and grey. Each woman had an attendant carrying an umbrella over her head. The procession, led by a band of half a dozen musicians, who were blowing their trumpets all the time, passed out of the village into a ploughed field of unbroken clods. A new staff, with a paper streamer floating from the top, had been planted in the middle of the field, with an upright spear and some matting tied round the foot of it. It was very hard moving over the rough clods, but the procession moved round the flagstaff three or four times. The bull was dragged along by the side of the procession, its pace hastened by the letting off of crackers between its feet. After tying the bull to the staff, all those present took up a position on one side of the field and prayers were chanted for a long time. Two trays containing meat and vegetables and pots of whisky were then brought forward, and after being offered to the dead, some of the food was eaten by the women.

'' After a long pause, a man mounted on the back of the bull and pulled a string hanging from the flagstaff, which let off bundles of crackers, and these went off one after another, many of them exploding in the face and about the head and feet and all around the bull. While the crackers were going off the procession moved round and round the staff, and, when the crackers were exhausted, left the ground and returned to the house, leaving the bull standing uninjured in the field. We were told that any one who had the courage to do so might approach the bull at dusk and despatch it. None of the family or kinsfolk of the deceased may eat any of the flesh of the bull, but acquaintances and others of the villagers might cut off and carry away what they pleased”

They seem to have no definite opinion as to how the dead are benefited by these offerings. Some of them say that in some way the bull, after it is killed, makes a hole in heaven so that the soul of the deceased may get in. They say also it is their custom to do these things: if they make these offerings it is better for the dead, whereas if they failed to do so the spirits of their ancestors would return and make no end of trouble for them. Fear, we think, is the chief motive in these sacrificial observances.

Bouyei Society and Life in the 1900s

Clarke wrote: We do not think the claim of the Bouyei to be Chinese has done them any good. They appear to have all the defects of the Chinese and none of their better qualities. Among the “ Chinese are good, bad, and indifferent: among the Bouyei some are bad, and the others perhaps not so bad. The Chinese generally describe the Miao as turbulent, simple, and without proper notions of propriety: while they describe the Bouyei as crafty, lying, and dishonest. This description would do for some of the Chinese themselves, but not for all. [Source: “Among the Tribes of South-west China” by Samuel R. Clarke (China Inland Mission, 1911)]

There are more schools in Bouyei villages than among the Miao, and consequently more of them can read and write. We have heard it said, and probably with a good deal of truth, that when a Bouyei can read and write he gives up working, to live by his wits. This is by no means a difficult way of making a living in China. Learning how to write pleas and counter-pleas, and methods of legal procedure, he is constantly in and about the Yamens [local officials], assisting in law cases, making profit for himself out of other people's difficulties, and continually, for obvious reasons, stirring up trouble among neighbours. Such men are a great nuisance all over China, and not least in out-of-the-way places.

The Bouyei districts and communities are ruled just the same as the rural Chinese. The headmen or local justices are generally wellto-do Bouyei, and many disputes are settled without appealing to the Chinese magistrate. But, like the Miao, the Bouyei are very litigious, and spend a good deal of their time and money in Chinese courts. The power exercised by local justices is very indefinite, so that one is sometimes surprised at their helplessness, and at other times amazed at the extraordinary power they seem to have. A leading Chinese Justice of the Peace once asked me what we did in our country to men who stole other people's crops. I replied that if the thief were caught, and the charge proved, he would be put in prison for some time. “Ah,'' he said, ''when I catch them I have them strangled; it's the best way to do with such people."

Bouyei Thieves in the 1900s

Samuel R. Clarke wrote in “Among the Tribes of South-west China”: “ The Chinese say that every Bouyei is a thief, and from what we know of them we should not feel justified in denying the charge. The thieves and robbers among the Miao prey upon travellers and distant hamlets, but the dishonest among the Bouyei are sneak thieves who prowl around, especially at night, and pilfer from their friends and neighbours. [Source: “Among the Tribes of South-west China” by Samuel R. Clarke (China Inland Mission, 1911)]

Living in the Miao villages, it is evident that the villagers trust one another, and will sometimes say to us when we appear overcareful about our belongings, “Don't be afraid, there are no thieves in this village." It is not so among the Bouyei. We remember once riding into a Bouyei village, and were almost deafened by twenty or thirty dogs who followed us, all barking at the top of their voices. When we had dismounted and entered the house in which we were to pass the night, I said to our host, “Well, we need have no fear of thieves in this village.'' “ Ah! “ he replied, “but we do fear them very much." “But," I said, “no thief could get near the place, the dogs make such a noise they would rouse every family in the village." Our host smiled and said, “If a thief comes he will not be a stranger, but a neighbour whom the dogs know very well and so will not bark at him. When anything is stolen during the night, the thief is sure to be a neighbour who sat round the fire, smoking and chatting and patting the dog during the evening."

About four years ago, in a Bouyei village some three miles from Guiyang, there was a well-known thief who was always stealing from his kinsfolk and neighbours. This at length so exasperated the villagers that they took the man, and in the presence of two local justices deliberated as to what was to be done with him. They decided that he was a man who could very well be spared, and with the consent of his parents, having bound him hand and foot, they threw him into a pond and drowned him. Subsequently some members of the culprit's family accused the two justices in the Prefect's Yamen of murdering the man. The justices were apprehended and kept in prison for several months, and only came out after they had been squeezed of about two hundred Mexican dollars.

We know of an exactly similar case in a Chinese village, where the local headmen also drowned a man and that was an end of the matter. Possibly in the latter case there was no one in the village who had a grudge against the headmen, or who had any interest in bringing the Yamen underlings on the scene: or possibly the headmen had friends in the Yamen who would have barred any proceedings against them. The magistrate and the Yamen staff are ostensibly for the collection of taxes and the administration of justice; actually they do collect the taxes, but also extort all the money they can from the people by what is called the administration of justice. Some of the taxes collected go into the Imperial exchequer, but all the money they get from litigation goes into the pockets of the magistrate, his secretaries, or his underlings.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Nolls China website

Text Source: “Among the Tribes of South-west China” by Samuel R. Clarke (China Inland Mission, 1911)

Last updated October 2022