GAOSHAN

The Gaoshan are Chinese ethnic minorities that lives mostly in Taiwan where have been subdivided into groups that have different names, only a small number live in China. There are about 500,000 Gaoshan. They mainly live in the middle mountain area, the flat valleys running along the east coast of Taiwan Island, the eastern Zhonggu Plain and on Lanyu Island of Taiwan. Based on differences in geographical location, language, and culture, the Gaoshan are further divided into several sub-groups, including the Aimei, Taiya, Paiwan, Bunong, Lukai, Beinan, Cao people (Zou people), Saiya, Yamai people as well as Pingpu people living scattered all over Taiwan and already basically assimilated with the Han Chinese there. In China there are about 4000 people classified as Gaoshan scattered in Fujian and Zhejiang Provinces on the mainland and Beijing. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences]

Gaoshan are regarded as the oldest nationality in Taiwan and considered to be the aboriginals of the island. During their history, they have been successively called "Shanyi," "Daoyi," "Dongfan," "Dongfan," "Fanren," "Gaolizu,"and "Fanzu". Taiwan authorities call them "compatriot of the mountain region" — "mountain compatriot" for short, or "aboriginal group," Gaoshan is a general name used by mainland people for all the minorities living in Taiwan.

According to historical record the Gaoshan have been living on Taiwan since the A.D. 3rd century. Most are farmers. Those that live near the sea are fishermen. Some live in stone plate houses. Men and women wear a straight sarong. Every year a ceremony is held to offer sacrifices to their ancestors. The Gaoshan are famous for their hair-tossing dance Their pestle dance depicts farm labor. A popular sport is the Spearing of the Rattan Ball. It is done with very long spears, about five meters in length, and originated as part of a religious ceremony.

Gaoshan speak languages that belong to the Indonesian group of the Malay-Polynesian language family. The differences between the languages of the different groups and subgroups is relatively great and these groups generally can not communicate with each other using their own languages. These days 15 kinds of languages are recognized, which can be roughly divided into three subgroups, Qinhuai, Cao and Paiwan. Most people classified as Gaoshan also speak and write Chinese, with those in Taiwan using the Taiwan dialect while those in China using Mandarin or southern dialects. Because different groups have lived in different natural conditions and their interaction with the Han culture has varied, their level of development is different, with higher levels of development among those living with Han people in the plain and lower levels among those living in mountain regions. Some groups practiced headhunting until the early 20th century. The economy relies mainly on the rice cultivation, supplemented by fishing and hunting. Millet, rice, potatoes and taro are their staple foods. They like drinking.

See Separate Articles under Taiwan factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Ethnic Minorities of China” by Xu Ying & Wang Baoqin Amazon.com; “Handbook on Ethnic Minorities in China” by Xiaowei Zang Amazon.com; “Minority Peoples of China” by OMF International Amazon.com; “China's Minority Nationalities” by Ma Yin (1989) Amazon.com; “China's Minority Nationalities” (1984) Amazon.com; China's Minority Nationalities” by Red Sun Publishers (1977) Amazon.com; “China's Ethnic Minorities” by Xiao Xiaoming Amazon.com; “Encyclopedia of World Cultures. Vol. 6, Russia and Eurasia/China” (1994) by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond Amazon.com; “Ethnic Groups in China” by Wang Can Amazon.com; “The 56 Colorful Ethnic Groups of China: China's Exotic Costume Culture in Color” by Xiebing Cauthen Amazon.com;

Gaoshan Population and Groups

The Gaoshan are the third smallest minority out of 55 in China. They numbered only 4,009 in 2010 and made up less 0.0003 percent of the total population of China in 2010 according to the 2010 Chinese census. Gaoshan population in China in the past: 4,488 in 2000 according to the 2000 Chinese census; 2,909 in 1990 according to the 1990 Chinese census. A total of 329 were counted in 1953; 366 were counted in 1964; and 1,750 were, in 1982. [Sources: People’s Republic of China censuses, Wikipedia]

The Taiwanese government recognizes 14 aboriginal ethnic groups. Their numbers range from several thousand members in the smaller groups, to the Amis group at nearly 190,000. Their total population is about half a million and growing overall. The 14 different tribes are the Amis, Atayal, Paiwan, Bunun, Puyuma, Rukai, Tsou, Saisiyat, Yami, Thao, Kavalan, Truku, Sakizaya, and Sediq. [Source: Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China, edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company]

In 1991, aboriginals numbered about 338,151. The major aboriginal groups and their numbers at that time were: 1) the Amis tribe (147,000), who reside near Hualin, the largest city on the east coast and at the southern tip of Taiwan; 2) the Atayal tribe (91,000), who live near Taipei, and around the Tapachien Mountain; 3) the Paiwan tribe (70,000), who come from southern Taiwan and live around Daladalai, a village that can be reached on foot from Santimen; and 4) the Bunun (41,000), who live in the mountains of central Taiwan. Smaller officially recognized groups include 5) the Puyuma (10,000) from southeast Taiwan; 6) the Rukai (12,000), from south-central Taiwan; 7) the Saisiyat (7,000) from northern Taiwan , near Taipei; 8) the Tsou, from central Taiwan; and 9) the Yami (4,000), who live on an island in the Philippine Sea. [Ibid]

Several thousand Gaoshans live on the mainland. They are scattered in Fujian and Zhejiang Provinces on the mainland and in major cities as Shanghai, Beijing and Wuhan. According to the Chinese government: “Though small in number, these Gaoshans have their deputies to the National People's Congress, China's supreme organ of power. They enjoy equal rights in the big family of all ethnic groups on the mainland. The Gaoshan people share the aspiration of all other ethnic groups in China for peaceful reunification of the motherland, so that people on both sides of the Taiwan Straits will be reunited.

Early History of Taiwan

It is believed that people have been residing on the island of Taiwan for around 15,000 to10,000 years (the oldest archeological evidence dates back to around 6,000 years ago) . The first residents are believed to have been aboriginal people from the Layan group who arrived in outrigger canoes from Pacific Islands to the east. The Layans are related to the early inhabitants of Southeast Asia, the Philippines and Australia.

According to Lonely Planet: “There is evidence of human settlement in Taiwan dating as far back as 30, 000–40, 000 years ago; current prevalent thinking dates the arrival of the Austronesian peoples, ancestors of many of the tribal people who still inhabit Taiwan, between 4000–5000 years ago.” Evidence of human habitation has been found on Minatogawa, an island between Taiwan and Japan, dated to 18,000 years ago.

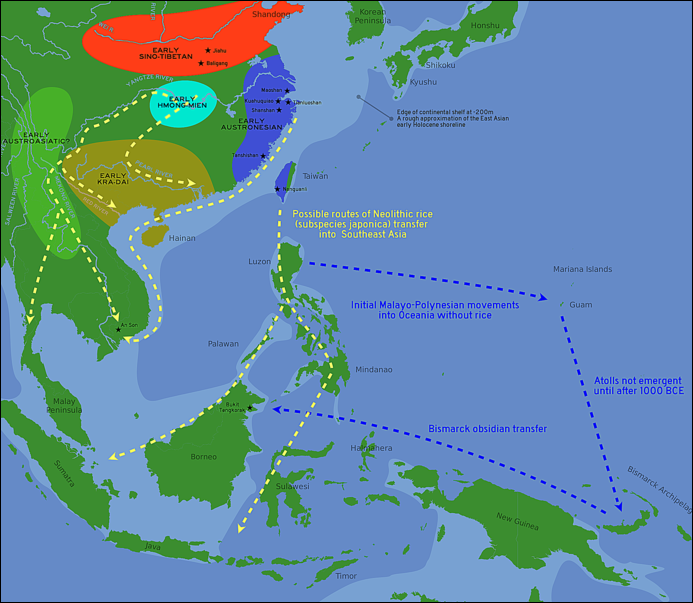

Evidence of Neolithic agrarian settlements, similar to those of coastal China, dating from 4000 to 2500 B.C., have also been found. Because there was no land bridge to mainland Asia, the supposition is that these Neolithic peoples were seafarers as well as agriculturalists. There are several theories as to the origins of the aboriginal, Austronesian-speaking peoples living in Taiwan today. Some scholars believe that the first people to populate Taiwan were Malayo-Polynesians, specifically from Indonesia—peoples of a southern origin. Others argue for a northern origin—tribal peoples from southeastern mainland China—in support of the argument that Taiwan has always been a part of China. Some have posited Taiwan as the origin of the Austronesian languages, a position supporting an early Neolithic migration from southeastern China followed by independent development in Taiwan. [Source: Library of Congress, March 2005]

Originally, Taiwan was settled by people of Malay-Polynesian descent, who initially inhabited the low-lying coastal plains. They called their island Pakan. Before the Chinese arrived Taiwan was occupied nine aboriginal tribes of Malaysian stock, each with their own language. Some were reputed to be head hunters. During the subsequent settlement by the Dutch and the waves of settlers from China, the aborigines retreated to the hills and mountains, and became the "mountain people."

Chinese Culture Spreads to Taiwan, Asia and the Pacific

Pottery and stone tools of southern Chinese origin dating back to 4000 B.C. have been found in Taiwan. The same artifacts have been found in archeological sites in the Philippines dating back to 3000 B.C. Because there were no land bridges linking China or Taiwan with the Philippines, one must conclude that ocean-going vessels were in regular use. Genetic studies indicate that closest genetic relatives of the Maori of New Zealand are found in Taiwan. [Source: Jared Diamond]

Southern Chinese culture, agriculture and domesticated animals (pigs, chickens and dogs) are believed to have spread from southern China and Taiwan to the Philippines and through the islands of Indonesia to the islands north of New Guinea. By 1000 B.C., obsidian was being traded between present-day Sabah in Malaysian Borneo and present-day New Britain in Papua New Guinea, 2,400 miles away. Later southern Chinese culture spread eastward across the uninhabited islands of the Pacific, reaching Easter Island (10,000 miles from China) around 500 A.D. [Ibid]

The ancestors of modern Laotians, Thais and possibly Burmese, Cambodians, Filipinos and Indonesians originated from southern China. The Austronesian family of languages of which are spoken as far west as Madagascar, as far south of New Zealand, as far east as Easter island and all Philippine and Polynesian languages most likely originated in China. A great diversity of these languages is found in Taiwan, which has led some to conclude they originated there or on the nearby mainland. Others believe they may have originated in Borneo or Sulawesi or some other place. The ancestors of modern Southeast Asian people arrived from Tibet and China about 2,500 years ago, displacing the aboriginal groups that occupied the land first. They subsisted on rice and yams which they may have introduced to Africa. Rice was introduced to Korea and Japan from China in the second millennium B.C.; bronze metallurgy in the first millennium B.C. and writing in the first or early second millennium A.D. Chinese characters are still used in written Korean and Japanese today.

Early History of Taiwan and the Chinese

For most of its long history, China seemed fairly indifferent to Taiwan. Early Chinese texts from as far back as A.D. 206 contain references to the island, but for the most part it was seen as a savage island, best left alone. The earliest recorded contacts between Taiwan and mainland China were during the Sui Dynasty (581 to 618 A.D.).

There are few references to Taiwan in the vast, comprehensive Chinese historical records other than vague references to the island during the Sung dynasty in the early 10th century. There are more references in more comprehensive texts in the 15th and 16th century, when Taiwan was used as base for Japanese, Portuguese, Dutch and Chinese pirates and traders. When the Dutch East Indies Company arrived in the early 17th century, they found only the aborigine population on the island: there were no signs of any administrative structure of the Chinese Imperial Government. Thus, at that time Taiwan was not "part of China". As is seen on a map of those days, it is shown in a different color.

The first Chinese to arrive in Taiwan perhaps migrated to the island in the A.D. 6th century. Mainland Chinese began to trade with the aborigines around the fourteenth century. Substantial numbers of Chinese migrants did not arrive until after the arrival in Taiwan in of the Portuguese in the 16th century. Large scale migration from the mainland did not begin until the 17th century, when political and economic chaos at the end of the end of Ming dynasty and the Manchu invasion drove many people out of southern China. Most of the migrants came from the nearby coastal provinces of Fujian and Guangdong.

According to Lonely Planet: Contact between China and Taiwan was erratic until the early 1400s, when boatloads of immigrants from China’s Fujian province, disillusioned with the political instability in their homeland, began arriving on Taiwan’s shores. When the new immigrants arrived, they encountered two groups of aboriginals: one who made their homes on the fertile plains of central and southwestern Taiwan and the other, seminomadic, lived along the Central Mountain Range. [Source: Lonely Planet ++]

Over the next century, immigration from Fujian increased, these settlers being joined by the Hakka, another ethnic group leaving the mainland in great numbers. By the early 1500s there were three categories of people on the island: Hakka, Fujianese and the aboriginal tribes. Today, Taiwan’s population is mainly descended from these early Chinese immigrants, though centuries of intermarriage makes it likely a fair number of Taiwanese have some aboriginal blood as well. ++

History of the Gaoshans

The ancestors of the Gaoshan were created by a merging immigrants from mainland China and Southeast Asia. In Three Kingdoms period (A.D. 220–280), Sun Quan, emperor of the Wu Kingdom, dispatched some troops to Taiwan. In a record of the expedition entitled "A Survey of Water and Soil by the Coast," are earliest record of Gaoshan. In the book, Taiwan is named as "Yizhou," and Gaoshan ancestors as "Shanyi". Emperor Yang of the Sui Dynasty (581–618 ) sent troops twice to Taiwan, when the Gaoshan people were named "Liuqiu people". [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities]

According to the Chinese government: “There are several versions of the origin of the ethnic minority. The main theories are: they are indigenous, they came from the west, or the south, or several different sources. The theory that they came from the west is based on their custom of cropping their hair and tattooing their bodies, worshipping snakes as ancestors and their language, all of which indicate that they might have been descendants of the ancient Baiyue people on the mainland. Another theory says that their language and culture bear resemblance to the Malays from the Philippines and Borneo, and so the Gaoshans must have come from the south. The third and more reliable theory is that the Gaoshan ethnic group originated from one branch of the ancient Yue ethnic group living along the coast of the mainland during the Stone Age. They were later joined by immigrants from the Philippines, Borneo and Micronesia.

Cementing close economic and cultural ties through living and working together over a long period of time, these peoples had by the time of the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368-1911) welded themselves into a new ethnic group known as Fan or Eastern Fan, which is today called the Gaoshan ethnic group.” [Source: China.org]

During the Tang, Song, and Yuan dynasties there were some exchanges between Taiwan and mainland. At this time influenced from Southeast Asia were arguably as significant as those from the mainland. By the Ming Dynasty, when the Gaoshan people were called "Dongfan," "Fanyi," "Tufan," or "Tumin," the cultural characteristics of the Gaoshan had already basically taken shape and the different groups had divided and distinguished themselves. ~

During the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912) government, Gaoshan people are referred to as "Fan nationality". They are further divided into many sub-groups including: 1) "Eastern Fan", "Western Fan", "Southern Fan", and "Northern Fan" by their where they lived; 2) "High Mountain Fan", and "Pingpu Fan" by the different terrain they are inhabited; or 3) "Ye Fan", "Sheng Fan" and "Shu Fan" by their level of social development or their relations with the Hans. ~

When the Japanese occupied Taiwan, they called Gaoshan people "Gaoli Nationality," or "Fan Nationality". After World War II, Taiwan authorities first used the name of "Gaoshan", but later replaced it with the terms "Mountain Region Compatriot," "Mountain Compatriot," and "Aboriginal People". On the mainland publication called the ethnic minorities that inhabited Taiwan for generations the "Gaoshan Nationality". In 1953, this name was affirmed by the Chinese government, and has been used up till today. ~

Chinese Take on Gaoshan and Taiwan History

According to the Chinese government: “Archaeological evidence suggests that the Gaoshan ethnic group has all along maintained close connections with the mainland. Until the end of the Pleistocene Epoch 30,000 years ago, Taiwan had been physically part of the mainland. Fossils of human skulls belonging to this period and Old Stone Age artifacts found in Taiwan show that humans probably moved there from the mainland during the Pleistocene Epoch. Neolithic adzes, axes and pottery shards unearthed on the island suggest that New Stone Age culture on the mainland was introduced into Taiwan 3,000 to 4,000 years ago. [Source: China.org |]

“In A.D. 230, two generals of the Kingdom of Wu led a 10,000-strong army across the Taiwan Straits, and brought back several thousand natives from the island. At that time, the ancestors of the Gaoshans belonged to several primitive, matriarchal tribes. Public affairs were run collectively by all members. Their tools included axes, adzes and rings made of stone and arrowheads and spearheads made of deer antlers. Animal husbandry was still in an embryonic stage. |

“By the early 7th century, the Gaoshans had started farming and livestock breeding on top of hunting and gathering. They planted cereal crops with stone farm tools. Each tribe was governed by a headman who summoned the membership for meetings by beating a big drum. There was neither criminal code nor taxation. Criminal cases were tried by the entire tribe membership. The offender was tied with ropes, flailed for minor offences or put to death for serious crimes. These early Gaoshans had no written language, nor calendar; and they kept records by tying knots. People worshipped the Gods of Mountain and Sea, and liked carving, painting, singing and dancing.

“In the Song and Yuan dynasties (960-1368), central government control was extended to the Penghu Islands and Taiwan, which were placed under the jurisdiction of Jinjiang and Tongan counties in Fujian Province. During the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), farming, hunting and animal husbandry further developed in Taiwan. In the early 17th century, an increasing number of Hans from the mainland moved to Taiwan, lending a great impetus to economic development along the island's west coast. |

“The Gaoshan and Han people in Taiwan worked closely together in developing the island and fighting against foreign invaders and local feudal rulers. Japanese pirates invaded Chilung, the major seaport in Northern Taiwan, in 1563. In 1593 the Japanese rulers tried to coerce the Gaoshan people into paying tribute to them but this demand was firmly rejected. The invasions of Japanese pirates from 1602 to 1628 were repeatedly beaten back. Towards the end of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), the Dutch and the Spanish time and again made forays into Taiwan, but were repulsed by the islanders. Finally, in 1642, the Dutch defeated the Spanish, seized the island and imposed tyrannical rule on the local people. This touched off immediate resistance. The anti-Dutch armed uprising led by Guo Huaiyi in the mid-17th century was the largest in scale. In April 1661, China's national hero Zheng Chenggong led an army of 25,000 men to Taiwan and freed it from under the Dutch with the assistance of the local Gaoshan and Han people, ending the Dutch invaders' 38-year-old colonial rule over Taiwan. |

“After recovering Taiwan from the Dutch, Zheng Chenggong instituted a series of measures to advance economic growth and cultural development there. He forbade his troops engaged in reclamation to encroach on the Gaoshan people's land, helped the local people improve their farm tools and learn more advanced farming methods from the Han people, encouraged children to attend school, and expanded trading. With the growth of production, the feudal system of land ownership came into being, and the gap between the rich and the poor was getting wider and wider. The feudal landlord economy developed in the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), when the Gaoshans began using ox-driven carts, ploughs and rakes developed by the Hans. Zheng died five months after recovering the island, and his son succeeded him. The Zhengs governed Taiwan for 23 years. In 1683, the Qing court brought the island under central government control and this rule lasted for 212 years till Taiwan fell under Japanese rule following the signing of the Sino-Japanese Treaty of Shimonoseki in 1895. |

“After the Opium War of 1840, British, American, Japanese and French colonialists invaded and plundered Taiwan one after another. The foreign invasion and plundering were met with fierce resistance. To fight the British invaders, the local people formed a volunteer army of 47,000 troops who beat back all the five British invasions. Taiwan fell into the hands of the Japanese in 1895 after China's defeat in the Sino-Japanese War. Fighting shoulder to shoulder for five months, Gaoshan and Han people inflicted 32,315 casualties on the Japanese invaders. |

“During the 20 years from 1895 to 1915, the people of Taiwan staged some 100 armed uprisings against Japanese occupation. One of them was the Wushe Uprising mounted by the Gaoshan people in Taichung County in 1930. Enraged by the murder of a Gaoshan worker by Japanese police, over 300 Gaoshan villagers wiped out the 130 Japanese soldiers stationed there and held Wushe for three days. In the following months, the insurgents killed and wounded more than 4,000 Japanese occupationists. In retaliation, the Japanese moved in most of their garrison forces in Taiwan along with planes and guns and crushed the uprising. They slaughtered over 1,200 Gaoshans including all the insurgents. After victory over Japan in 1945, Taiwan was returned to China and placed under Kuomintang rule.” |

Righteous Man Wu Feng and the Headhunters

The national museum of Central University for Nationalities possesses an extremely important historical relic of Gaoshan ethnic group: the 42-centimeter-tall wooden "sculpture of righteous man Wu Feng". In many ways it is an unexceptional wood carving work. What makes it so precious is the heart-breaking story behind it. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities~]

Wu Feng (1699-1769) lived in Zhuluo (present-day Jiayi) in Taiwan. His ancestral home was Pinghe County in Fujian Province. Though he was Han Chinese, he spent a lot of time among the Gaoshan and understood their languages and worked hard to improve their lives. In 1722, Wu was sent to live among the Cao people, a tribe of headhunters, in the Alishan region. He served as an interpreter and set up an office in a Gaoshan stockaded village.

Each autumn the Cao people hunted the heads of people from other tribes to hold a memorial ceremony for god. After Wu took up his official post, the Cao planned to hunt heads as usual. After Wu learned that, he did his utmost to talk them out of it as rid themselves of ths terrible custom. He told them, "It is heartless to kill innocent people." He advising them to stop killing and also suggested them to use 40 human skulls hunted before to offer as sacrifice, one for each year. After hearing his words, people felt his suggestions were reasonable and followed them. Wu had cattle, sheep, and clothes sent to Gaoshan people and ordered soldiers under him to help with the harvest and participate in their memorial ceremony to the gods. For more than 40 years, the Cao didn’t hunt human heads. After the 40 years were up, when all the stored human skulls were used up, Wu managed to delay two years.

During the third year, the Cao were unable to restrain themselves any longer and insisted on resuming human head hunting. Realizing the great challenge before him, Wu was determined to sacrifice his own life to persuade and educate Gaoshan people. He said, "Your killing custom should not be tolerated by the law! But you and I have already made it clear at the beginning that I will help you tackle this problem. Tomorrow morning, one wearing red clothes and cap will pass by the village; you can kill him and get his skull. But you must not kill others, or the gods will get angry and punish you. " The next day, August 10, 1769, a man as described by Wu appeared at the appointed time and was shot by Cao arrows. Shouting and jumping for joy, the hunters went up to cut off his head, only to find that the person they shot was Wu. It is said that Wu closed his eyes as the blood spurted out of his body. The head hunters were overcome with sadness and guilt and sobbed uncontrollably. Even trees all over the mountains, the story goes, and the morning wind let out a deep wail for him.

To commemorate Wu's heroic behavior, the local Gaoshan people cut trees and cogongrasses to set up temples, pavilions and platforms to hold memorial ceremonies regularly for him. They also vowed to follow Wu's words and never hunted human head any more. Later, Gaoshan people set up a square stone tablet, on which it was carved "Righteous man Wu sacrifices his life here". By the tablet a gigantic bronze statue of Wu riding a horse was erected and two banyan trees were planted. In 1820, the interpreter in Alishan took charge of building Wufeng Temple, also named as Alishan Zhongwang Temple" or Chengren Temple, to honor Wu. Every August 10 on the lunar calendar, the temple attracts many visitors who burn incense and worship him.

Gaoshan Religion

The Gaoshans are animists who believe in immortality and ancestor worship. They hold sacrificial rites for all kinds of occasions including hunting and fishing. The dead are buried without coffins in the village graveyard. There are vestiges of the worship of totems — snakes and animals — and certain taboos still remain. [Source: China.org]

Gaoshan retain many shamanist beliefs that emphasize a universe filled with spirits and mysterious supernatural powers. Holidays and rituals—including the seeding ceremony, safety ceremony, weeding ceremony, the fifth anniversary ceremony, ancestor's spirit ceremony, fishing hunting ceremony, short spirit ceremony, ship ceremony, harvest ceremony, bamboo pole ceremony, hunting ceremony, flying and fish ceremony— usually feature some kind of sacrificial offering. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

The religious beliefs of the Gaoshan are complicated and include elements of Buddhism, Taoism and Christianity. Several kinds of religions have developed among the different Gaoshan groups. Deities worshipped by the Gaoshan vary from place to place and group to group, but include a heaven deity, universe-creating deity, nature deity, Sili deity and some other spirits and ghosts. Sacrifices include agriculture sacrifices (cultivation sacrifice, sowing sacrifice, weeding sacrifice, harvest sacrifice), hunting sacrifices, fishing sacrifices, and sacrifices and offerings to ancestors. Shamanism and folk religion are still strong in some places. Methods of fortunetelling, soothsaying and divining include bird-fortunetelling, dream-fortunetelling, water-fortunetelling, and rice-fortunetelling. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

Gaoshan Totems

According to historical documents, folk myths and legends and the scholarly research, nine Gaoshan tribes all have their own totem customs. There are various totem things. Some are animals and plants, such as the chicken, dog, ox, monkey, deer, lion, snail, tortoise, worm, bird, snake, fish, trees, bamboo or calabash tree; some are inanimate objects and natural phenomena such as huge stones, floating clouds, rosy clouds, lightning, mountains, rivers, lakes and seas. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

Paiwan people are particularly well-known for their worship the totem of snake. The Paiwan have many mythical stories of snakes laying eggs and giving birth to their ancestors. They have traditionally believed that they are blood relatives with snakes and that snakes are their patron gods and possessors of supernatural powers and can protect the Paiwan from difficulties, sufferings, and misfortune. ~

In order to maintain good relations with their totem god and keep getting their help and protection, Paiwan people can not kill, eat or harm snakes. Also, they carve and paint snake images on their houses, ancestors' spirit posts, weapons as well as on various kinds of utensils such as wineglasses, spoons, tubes, and pots. Things carved or painted with the snake images are considered to be holy. When facing or using them, one is expected to be respectful and refrain from profanity. ~

Gaoshan Festivals

Gaoshan festivals typically feature feasting, singing, dancing, games and sports. The harvest festival is celebrated by all Gaoshan people excluding the Yamei people. Regarded as the grandest festival among the Gaoshan ethnic group, their equivalent to Chinese New Year, it is celebrated in the harvest season, in the seventh or eighth lunar month and lasts six to 10 days. Because different tribes live in different areas, where different crops are harvested at different times, the festival is celebrated at different times. However, most of the festivals have some common features: namely when each link in the harvest chain (gathering, tasting the new crop and stpring) starts or finishes, rituals are held that feature offering sacrifices and prayers to thank the ancestor gods for this year’s harvest and get their blessing for next year’s harvest. After the rites, Gaoshan eat, sing and dance together, play games and hold bonfire parties. ~

Gaoshan people like having feasts and enjoy singing and dancing during festivals or important occasions. The feats typically involve slaughtering pigs and cattle, and preparing and drinking lots of wine. To mark the the end of the year, Bunong people use the leaves from the “Xinuo” plant to wrap glutinous rice, then steam it and eat it. Other foods eaten at by Gaoshan at festive occasions include cakes and Ciba (cooked glutinous rice pounded into paste) made of various kinds of glutinous rice, which are not only eaten as desserts and snacks, but also offered as sacrificial ceremonies. Glutinous rice is a fixture meals to entertain guests. Offerings and sacrifices are also a big part of Gaoshan gatherings. These include ancestor offerings, grain deity offerings, mountain deity offerings, hunting deity offerings, marriage offerings and harvest offerings, among which, the Wunianji (Five Year Offerings) of the Paiwan people is the grandest. Festivals also often feature many sports and recreational activities. At wedding feasts lots of wine is prepared and guests are expected to get very drunk. [Source: Chinatravel.com]

Gaoshan Marriage and Funeral Customs

According to the Chinese government: “The Gaoshans are monogamous and patriarchal in family system, though the Amei tribe still retains some of the vestiges of the matriarchal practice. Commune heads are elected from among elderly women and families are headed by women, with the eldest daughter inheriting the family property and male children married off into the brides' families. In the Paiwan tribe, either the eldest son or daughter can be heir to the family property. All the Amei young men and some of the Paiwan youths have to live in a communal hall for a certain period of time before they are initiated into manhood at a special ceremony.[Source: China.org]

Burial ceremonies vary. Taiya people, Bunong people and Cao people usually bury the dead under their bed inside their room. Paiwan people and Dawu people bury the dead in the forest. Amei people generally bury the dead in the open ground in front or behind the house, but for people who died a violent death, their bodies are buried at the places where the person died. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

Gaoshan Life, Society and Taboos

There are many kinds of traditional houses, such as log cabins, bamboo huts, thatched cottages and slate building—most of which are rectangle or square. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

The "She" is the basic social organization unit of the Gaoshan ethnic group. It began as a clan organization based on blood relationship, and later gradually developed into a social organization made up of several clans, which live together in compact communities and are unified by blood relationship and geographical region. The name "She" started to be used during the Ming and Qing dynasties. At that time, Gaoshan villages were called "Fan She" or "She". The Taiwan Province Survey counted 409 "She" in the Qing Dynasty. Later on, they merge into 30 "mountain villages", under the jurisdiction of 12 counties respectively. Today, the name "She" has largely disappeared but its function and influence in village life is still very much alive. ~

The boundaries between "She" are clearly demarcated. Every "She" has its own name, and elects its own head. Within one "She", people share the common living customs and economic benefits and work together as a group towards common goals. People are bonded together with their common faith and practice of offering sacrifices. The members are under obligations to work as a unit and help each other. The size of "She" varies, from dozens of household to several hundred or even thousands of them. Sometimes big "She" have jurisdiction over smaller "She".

Gaoshan taboos: 1) It is considered inauspicious to see someone who died a violent death and their burying place, or animals mating. 2) It is inauspicious to touch a fetish or stuff of the dead. 3) Women cannot touch hunting equipments and weapons that men have used, such as bow, arrow, gun or spear. 4) Women cannot enter a men’s place or sacrificial venues except at special times. 5) Men cannot touch the loom or raw hemp that women have used. 6) When people are out fishing, hunting or attending sacrificial ceremonies, the fire set up at their home should not be extinguished. 7) During sacrificial ceremonies, it is not allowed to eat fish or sneeze. 8) Gaoshan people in the southern region of Taiwan believe that the spirit goes out of the human body while sneezing, which will attract evil spirits, increasing the chance of disasters. 9) Giving birth to twins is viewed as inauspicious as is believed that the twins are wild beasts which predict the coming of disasters. In the past, they would kill one of the twins to ward off the disaster. 10) Illegitimate children have traditionally been strictly forbidden and in the past were abandoned to the wild. 11) Fathers should not touch their babies, because Gaoshan believe that the babies are fragile and their fragility will infect a father and cause him to lose strength and affect his ability to hunt. This very unusual taboo is a “policy” to ensure that the custody of children belongs to mothers in matrilineal society.

Gaoshan Food and Drinking Customs

Gaoshan people mainly eat grains and root vegetables, including chestnuts, rice, potato and taro, accompanied by coarse cereals, edible wild herbs and in some cases wild preys. In mountainous areas, the staple foods include chestnuts and upland rice. In plain areas, the staple food is paddy rice. Except for Yamei people and Bunong people, the Gaoshan subgroups eat rice as their daily food, accompanied by potatoes and coarse cereals. Yamei people living in Lanyu Islet mainly eat taro, millet and fish. Bunong people mainly eat millet, corn and potatoes. [Source: Chinatravel.com]

Gaoshan people are fond of smoking, drinking and chewing betelnut. With the exception of the Yamei people, Gaoshan people generally like drinking. They have traditionally made their own wine and drank it celebrating weddings, baby births, happy events, house building and as part of farming, fishing and hunting ceremonies. Traditional drinking vessels include wooden dippers, bamboo tubes, wooden spoons, wooden cups, pottery jars and pottery cups. The joint wooden cup of Paiwan people is particularly characteristic.[Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities]

Gaoshan Garements and Shellfish Clothes

clothes made with shellfish

Among the Gaoshan there are many varieties of traditional clothing, including pass- through-head clothing, no-sleeves Jiaoling clothing, corselets, undershirts, long sleeve jackets, and skirts. Shellfish, animal bone, fish bone, and feathers are favorite ornaments.

The clothes of the Gaoshan people are beautiful and colorful. Traditional clothing styles include pass- through- head clothing, Jiaoling clothing, corselets, undershirts, long sleeves jackets and skirts. Ornaments worn by both men and women includes head ornaments, forehead ornaments, ear ornaments, neck ornaments, chest ornaments, waist ornaments, arm ornaments, hand ornament and foot ornaments. The ornament materials are mainly natural things, such as shells, shellfish pearls, pig teeth, bear teeth, feathers, animal skins, bamboo tubes and flowers as well as glass balls and beads. Among these things, shellfish are perhaps the most extensively used. They are not just stringed together into ornaments, but, among the Taiya people and Saixia people, they are also sewn onto jackets in clusters to make precious shellfish clothes.[Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities]

Gaoshan clothes are generally made of hemp and cotton. In some places clothes made with home-weave linen with color stripes are still worn. Men's wear includes capes, vests, short jackets and pants, leggings and turbans decorated with laces, shells and stones. In some areas, vests are delicately woven with rattan and coconut bark. Women wear short blouses with or without sleeves, aprons and trousers or skirts with ornaments like bracelets and ankle bracelets. They are skilled in weaving cloths and dyeing them in bright colors and they like to decorate sleeve cuffs, collars and hems of blouses with beautiful embroidery. They also use shells and animal bones as ornaments. In some places, the time-honored tradition of tattooing faces and bodies and denting the teeth has been preserved. Some elderly Gaoshan women, though having lived on the mainland among the Han people for many years, still take pride in their distinctive embroidery. [Source: China.org |]

In northern Gaoshan areas, people usually wear sleeveless jackets, top and belts. In the central part, people have traditionally worn deerskin waistcoats, waist band and tops and black-cloth skirts. In the southern areas, people usually wear long-sleeved coats with buttons down the front, skirts, leggings and black head cloth. Women wear long coats with short skirts or short coats with long skirts. Yamei people’s clothes are very simple. Men wear sleeveless sweaters and a piece of cloth to cover their private parts. Women wear sleeveless sweaters and tight skirts. In winter, they cover the body with quadrate cloth. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

According to the Shanghai Museum: The chief of the Atayal of Gaoshan people in Taiwan used to wear the shell-bead vest as a symbol of wealth. It is threaded with nearly 100,000 carefully polished tiny shell-beads. Thread the irregular beads first and then polish them on the sand paper till they become regular, and then sew them on linen to make the vest. As the shell bead vest is very time consuming and features unique craft, simple as it is, it is a symbol of status and wealth. [Source: Shanghai Museum]

Shellfish clothes are made up of two pieces of cloth, sewn with bunches of shellfish pearls. To make them: 1) cut the shells into small thin slices; then grind them carefully into the pearl shape; 2) after that, string every grain of small shell pearl together and sew them onto the front and either side of cloth garment, sometimes even the whole thing. Depending on the materials used, they are called shellfish clothes, shellfish pearl clothes or pearl clothes. Each piece of shellfish clothes requires tens of thousands of to hundreds of thousands of shell pearls. The process of making a piece of shellfish clothes is complicated and difficult, and requires lots of time and energy. As a result, they have traditionally been symbols of power and wealth only possessed by tribal chiefs and rich people. There are fine examples of such clothes at the the national museum of the Central University for Nationalities and the anthropology museum of the Xiamen University. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities]

Gaoshan Culture

The Gaoshan are also highly skilled in handicrafts. Their rattan and bamboo weaving, including baskets, hats and armors, pottery utensils, wooden mortars and pestles and dugout canoes are unique in design and decoration. In the mountains, the Cao and Bunong tribes are experts in tanning hides, while the Taiya tribe makes excellent fishing nets. Other crafts include weaving, carving and pottery making. [Source: China.org |]

hair swinging dance

The folk literature of Gaoshan ethnic group includes fairy tales, legends, odes to ancestors, folk songs, myths, legends and stories. Songs and dances are very much a part of Gaoshan life. On holidays, they would gather for singing and dancing. They have many ballads, hunting songs, dirges and work songs. Their folk songs touch on a variety of subjects including farming, fishing and hunting, wars and bravery in fighting. Instruments include the mouth organ, nose flute, and bamboo flute. One musical form unique to the Gaoshans is a work song accompanying the pounding of rice. |

Gaoshan art includes a great deal of carving and painting of human figures, animals, flowers and geometric designs on wooden lintels, panels, columns and thresholds, musical instruments and household utensils. Hunting and other aspects of life are also depicted, and figures with human heads and snake bodies are a common theme. |

Wood carvings from the Gaoshan people convey a sense of boldness, as exemplified by the human figures and painted fishing boats that they crafted. Wooden fishing boats made with carved and painted design were produced by people living on Lanyu Island. Made from various woods, they resembled large decorated canoes. The carved deigns typically were clan marks painted red, white and black. [Source: Shanghai Museum]

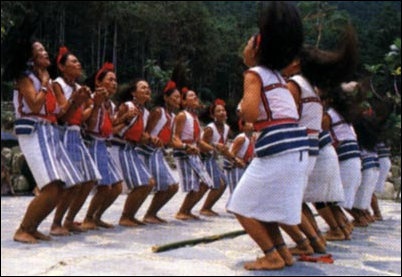

Gaoshan "Hair Swinging Dance"

Gaoshan enjoy singing and dancing. Almost all feasts, get-togethers and festivals feature lyrical songs and dance. Some dances simulate the movements of fishing, hunting, and farming. Group dances are especially exciting and popular. The number of participants varies from a few dozen to several hundred, even thousands of dancers. Often with the bonfire as the center, people drink, sing, and dance. Forming a circle hand in hand, dancers stamp their feet, jump, shake their bodies, and wave their hands rhythmically. The "hair swinging dance" is particularly representative of the “bold, unstrained, and optimistic spirit” of the Gaoshan. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

The "hair swinging dance" is a unique dance of Yamei women. Generally, the number of participants is not restricted, but long hair is required. When dancing, the women form a line and wave their bodies and hair slowly, with their arms held together, their hands placed on their chest, their steps moving back and forth. With the quickening of the music, the swing range of the body and head grows larger and larger, and the dance gradually enters into climax: with the women stepping forward, bending their knees and waists, swinging their long hair forward, stepping backwards, straightening their waists, swinging their hair rapidly. The movement goes on like this again and again, with the hair frequently striking the ground, ~

Gaoshan Agriculture

The Gaoshans are mainly farmers growing rice, millet, taro and sweet potatoes. Those who live in mixed communities with Han people on the plains work the land in much the same way as their Han neighbors. For those in the mountains, hunting is more important, while fishing is essential to those living along the coast and on small islands. Gaoshan traditions make women responsible for ploughing, transplanting, harvesting, spinning, weaving, and raising livestock and poultry. Men's duties include land reclamation, construction of irrigation ditches, hunting, lumbering and building houses. For transportation in rugged terrain, the Gaoshans have built bamboo and rattan suspension or arch bridges and cableways over steep ravines. [Source: China.org |]

According to the Beijing government: “Flatland inhabitants entered feudal society at about the same time as their Han neighbors. Private land ownership, land rental, hired labor and the division between landlords and peasants had long emerged among these Gaoshans. But, in Bunong and Taiya, land was owned by primitive village communes. Farm tools, cattle, houses and small plots of paddy field were privately owned. A primitive cooperative structure operated in farming and the bag of collective hunting was distributed equally among the hunters with an extra share each to the shooter and the owner of the hound that helped.” |

Image Sources: Chinese government

Text Sources: 1) “Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China”, edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company; 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn ~; 3) Ethnic China \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org |

Last updated October 2022