CHINESE IN THE UNITED STATES

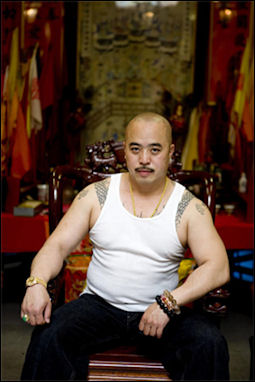

Raymond Shrimp Boy Chow's

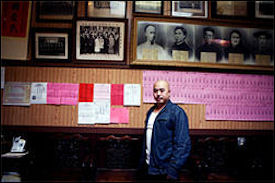

San Francisco tong members

The Chinese American community is the largest overseas Chinese community in North America, closely followed by the Chinese communities in Canada and Mexico. It is also the fourth largest in the Chinese diaspora, behind the Chinese communities in Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia. The Chinese American community comprises the largest ethnic group of Asian Americans, comprising 25.9 percent of the Asian American population as of 2010. Americans of Chinese descent, including those with partial Chinese ancestry constitute 1.2 percent of the total U.S. population as of 2010. According to the 2010 census, the Chinese American population numbered approximately 3.8 million. In 2010, half of Chinese-born people living in the United States lived either in California or New York. [Wikipedia]

The New York Times reported: Chinese Americans and Chinese in America are fragmented groups, divided by language, lineage, class and political history. There is often a sharp divide between newcomers and those who are more established. The first generation typically sends money back to needy relatives in hometowns. Those who are more established tend to give their money to mainstream institutions or art and education programs that emphasize an appreciation of their culture.

In the 2000 U.S. census, 2.43 million Americans described themselves as Chinese Americans. Some Chinese in the United States refer to themselves as ABCs (American-born Chinese). China, India and South Korea are the three largest exporters of university students to the United States. See Education, Universities

Between 2006 and 2010, Bonnie Tsui wrote in The Atlantic, “the number of Chinese immigrants to the U.S. has been on the decline, from a peak of 87,307 in 2006 to 70,863 in 2010. Because Chinatowns are where working-class immigrants have traditionally gathered for support, the rise of China—and the slowing of immigrant flows—all but ensures the end of Chinatowns.[Source: Bonnie Tsui, The Atlantic, December 2011. Tsui is the author of “American Chinatown: A People’s History of Five Neighborhoods”]

Many new Chinese arrivals to the United States have adjustment problems. Describing his first flight to the United States in 1985, a character in novel the U.S.-based Chinese writer Ha Jun said, “he and his fellow travelers, most of whom were students, had been nauseated by a certain smell on the plane’so much so that it made them unable o swallow the in-flight meal of Parmesan chicken served in a plastic dish. It was a typical American odor that sickened some new arrivals. Everywhere in the United States there was this sweetish, smell, like a kind of chemical, especially in the supermarket, where even vegetable and fruit had it. Then one day in the following week Nan suddenly found that his nose could no longer detect it.”

In New York, Chinese outnumber every nationality but Dominicans. The number of Chinese immigrants was up 53 percent in the 1990s alone. The top five sources of legal immigrants in the United States in 1995 were: 1) Mexico; 2) the Philippines; 3) Vietnam; 4) the Dominican Republic; and 5) China. A total of 36,900 Chinese emigrated legally to the United States in 1998. Countries with the most nationals given U.S. visas in 1998 were: 1) South Korea (619,011); 2) Brazil (575,041): 3) Mexico (548,716); 4) Taiwan (344,901); 5) China (250,503); 6) India (249,715); 7) Britain (243,921); 8) Columbia (176,438); 9) the Philippines (145,043); 10) Israel (129,580).

See Separate Articles HISTORY OF CHINESE AMERICANS AND IMMIGRANTS IN THE UNITED STATES factsanddetails.com ; SNAKEHEADS AND ILLEGAL CHINESE IMMIGRANTS factsanddetails.com ; FAMOUS CHINESE AMERICANS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Chinese in America: A Narrative History” by Iris Chang Amazon.com; “Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother” by Amy Chua (Penguin Press, 2010) Amazon.com ; “Driven Out: The Forgotten War Against Chinese Americans” by Jean Pfaelzer Amazon.com; “Ghosts Of Gold Mountain: The Epic Story of the Chinese Who Built the Transcontinental Railroad” by Gordon H. Chang Amazon.com; “The Snakehead: An Epic Tale of the Chinatown Underworld and the American Dream” by Patrick Radden Keefe Amazon.com; “Tong Wars: The Untold Story of Vice, Money, and Murder in New York's Chinatown” by Scott D. Seligman, David Shih, et al. Amazon.com

Fujians and Taishanese in the United States

Most of the 30,000 Chinese illegal aliens that enter the United States every year are from Fujian Province. More than 100,000 leave annually for other countries. Many Fujians — also called Fujianese or Fukinese — come from a series of villages along the Min River. Most have come to the United States to seek a better life.

An estimated 300,000 Fujians are scattered across the United States, living in almost every state. Many employers seek them because they are regarded as hard working. Many job listing have the Chinese characters for "no north," which means that people from southern provinces such as Fujian are preferred.

Contrary to what many people think, Fujian is not once of the poorest provinces in China. It is in fact is one of the richest. People have relatively high incomes but often the only way for them to advance further or quickly is to go aboard. In addition, Fujians can often afford the $50,000 snakehead fees necessary to reach the United States that Chinese from other provinces can not.

Many of the Chinese in Los Angeles and Australia are Taishanese, originating form the Taishan area about five hours west of Hong Kong, They first made their way to America via Hong Kong about 70 years ago. Many ended up in Hill Street or Broadway in Los Angeles or in the San Gabriel Valley, where they worked as cooks and waiters in their own restaurants. Today there are about 1 million Taishanese in Taishan and another 1.2 million in Hong Kong, Los Angeles and elsewhere around the world.

Emigration and Immigration in China in the 1970s and 80s

Through most of China's history, strict controls prevented large numbers of people from leaving the country. In modern times, however, periodically some have been allowed to leave for various reasons. For example, in the early 1960s, about 100,000 people were allowed to enter Hong Kong. In the late 1970s, vigilance against illegal migration to Hong Kong was again relaxed somewhat. Perhaps as many as 200,000 reached Hong Kong in 1979, but in 1980 authorities on both sides resumed concerted efforts to reduce the flow. [Source: Library of Congress]

“In 1983 emigration restrictions were eased as a result in part of the economic open-door policy. In 1984 more than 11,500 business visas were issued to Chinese citizens, and in 1985 approximately 15,000 Chinese scholars and students were in the United States alone. Any student who had the economic resources, from whatever source, could apply for permission to study abroad. United States consular offices issued more than 12,500 immigrant visas in 1984, and there were 60,000 Chinese with approved visa petitions in the immigration queue.

“Export of labor to foreign countries also increased. The Soviet Union, Iraq, and the Federal Republic of Germany requested 500,000 workers, and as of 1986 China had sent 50,000. The signing of the United States-China Consular Convention in 1983 demonstrated the commitment to more liberal emigration policies. The two sides agreed to permit travel for the purpose of family reunification and to facilitate travel for individuals who claim both Chinese and United States citizenship. Emigrating from China remained a complicated and lengthy process, however, mainly because many countries were unwilling or unable to accept the large numbers of people who wished to emigrate. Other difficulties included bureaucratic delays and in some cases a reluctance on the part of Chinese authorities to issue passports and exit permits to individuals making notable contributions to the modernization effort.

“The only significant immigration to China has been by the overseas Chinese, who in the years since 1949 have been offered various enticements to return to their homeland. Several million may have done so since 1949. The largest influx came in 1978-79, when about 160,000 to 250,000 ethnic Chinese fled Vietnam for southern China as relations between the two countries worsened. Many of these refugees were reportedly settled in state farms on Hainan Island in the South China Sea.

Jobs Performed by Immigrant Chinese in the United States

Lacking even basic English skills, most immigrants get low-visibility, low-wage jobs in the kitchens or restaurants or in garment factories. Chinese run many of the laundries in New York.

Chinese in the United States make up one percent of population but Chinese restaurants account for one third of the ethnic restaurants. Because of a glut of Chinese restaurants in New York City, many Chinese emigrants have opened up taco stands, Mexican restaurants and sushi bars.

Many women work in sweatshops. Those that have babies often send them back to China because they are so in debt to smugglers who brought to them the United States they can not afford to take off any time off from work. The children are taken back to China by a friend of friends for $1,000 plus airfare. The children, U.S. citizens by birth, are taken care of by their grandparents.

San Francisco's and Washington's Chinatown

San Francisco's Chinese-American community makes up a large proportion of the city's population. San Francisco’s New Year’s parade, with its 200-foot-long dragon, is regularly cited as the largest Chinese New Year celebration outside China. It’s sponsored by Southwest Airlines, and bleacher tickets cost $30 a piece. [Source: Monica Hesse, Washington Post, January 4, 2012]

Raymond Shrimp Boy Chow

head of San Francisco tong Michelle Locke of AP wrote: ‘san Francisco's Chinatown is the district that almost wasn't. After the 1906 earthquake, city leaders pressed for relocating the Chinese to the city outskirts. But Chinatown businessmen pointed out that getting rid of the Chinese immigrants would also mean losing the rents and taxes they paid. They came up with a plan to rebuild the area and make it a tourist attraction that would bring more money to the city. American architects were hired to create the new district, and pagodas were slapped up just about everywhere along with generous helpings of red, gold and dragons. Chinatown's outward appearance may be more picturesque than authentic, but what goes on behind the colorful facades is the real deal.” [Source: Michelle Locke, AP]

“Everywhere you turn there are things to see, like the markets on Stockton Street that have all manner of foods still swimming, clucking and croaking. There are plenty of places to eat in Chinatown, from hole-in-the-wall noodle shops to dim sum palaces...Tucked into narrow Ross Alley, the Golden Gate Fortune Cookie Factory is the kind of place you smell before you see — the sweet, sugary scent of baking cookies floats out the door. It's a tiny place where workers fold cookies by hand. You can buy a bag of your own for a few dollars.”

Monica Hesse wrote in the Washington Post, "The Chinese population within Washington Post D.C. has increased over recent years; it’s around 5,200 now, compared with about 3,700 in 2000. There are about 92,000 people of Chinese ancestry in the Washington metropolitan region...There’s a perception of scatteredness — that Chinatown’s bloated rents have caused residents to create Chinaburbs in Virginia and Maryland, or outposts elsewhere in the District. In recent years, as the neighborhood has been overshadowed by Verizon Center, independent restaurants and markets closed and the likes of Starbucks and Corner Bakery opened, festooned with Chinese characters. [Source: Monica Hesse, Washington Post, January 4, 2012]

Chinatown in New York

There are over 375,000 Chinese living in New York City. New York's Chinatown is the home of the largest Chinese community in the United States — about 200,000 people. There are large numbers of Chinese in Brooklyn, particularly Sunset Park and Sheepshead Bay.

Most Chinese in New York have traditionally been Cantonese but in recent years the Fujians made have become a large presence. In New York many Chinese pretend to live in squalid dungeon basement flats with makeshift bunks and scurrying rats so they can get preferential treatment in getting public housing.

Many residents of Chinatowns in the U.S. belong to traditional family-based organizations such as the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Assn (CCBA). As members they can find people who speak their local Chinese dialect and enjoy a "family feeling." The CCBA also mediates disputes, registers businesses and regulates numerous other activities.

End of American Chinatowns?

Bonnie Tsui wrote in The Atlantic, “As the manager of a Chinatown career center on Kearny Street in San Francisco, Winnie Yu has watched working-class clients come and go. Most of them, like Shen Ming Fa, have the makings of the quintessential Chinese American immigrant success story. Shen, who is 39, moved to San Francisco with his family last fall, an English-speaking future in mind for his 9-year-old daughter. His first stop was Chinatown, where he found an instant community and help with job and immigration problems. [Source: Bonnie Tsui, The Atlantic, December 2011 +++]

But lately, Yu has been seeing a shift; rather than coming, her clients have been going—in pursuit of what might be called the Chinese Dream. “Now the American Dream is broken,” Shen tells me one evening at the career center, his fingers drumming restlessly on the table; he speaks mostly in Mandarin, and Yu helps me translate. Shen has mostly been unemployed, picking up part-time work when he can find it. Back in China, he worked as a veterinarian and at a school of traditional Chinese culture. “In China, people live more comfortably: in a big house, with a good job. Life is definitely better there.” On his fingers, he counts out several people he knows who have gone back since he came to the United States. When I ask him if he thinks about returning to China, he glances at his daughter, who is sitting nearby, then looks me in the eye. “My daughter is thriving,” he says, carefully. “But I think about it every day.” +++

“Smaller Chinatowns have been fading for years—just look at Washington, D.C., where Chinatown is down to a few blocks marked by an ornate welcome gate and populated mostly by chains like Starbucks and Hooters, with signs in Chinese. But now the Chinatowns in San Francisco and New York are depopulating, becoming less residential and more service-oriented. When the initial 2010 U.S. census results were released in March, they revealed drops in core areas of San Francisco’s Chinatown. In Manhattan, the census showed a decline in Chinatown’s population for the first time in recent memory—almost 9 percent overall, and a 14 percent decline in the Asian population. +++

“The exodus from Chinatown is happening partly because the working class is getting priced out of this traditional community and heading to the “ethnoburbs”; development continues to push residents out of the neighborhood and into other, secondary enclaves like Flushing, Queens, in New York. But the influx of migrants who need the networks that Chinatown provides is itself slowing down. Notably, the percentage of foreign-born Chinese New Yorkers fell from about 75 percent in 2000 to 69 percent in 2009. +++

“Chinatowns almost died once before, in the first half of the 20th century, when various exclusion acts limited immigration. Philip Choy, a retired architect and historian who grew up in San Francisco’s Chinatown, has observed the neighborhood population of Chinese immigrants being replaced by new generations of Chinese Americans. “Chinatown might have disappeared if it weren’t for the changing immigration policies,” he told me recently. Only after the 1965 Immigration and Naturalization Act lifted quotas did the Chinese revive Chinatowns all across the country—especially those communities in New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. +++

“Of course, since the days of the Gold Rush, the Chinese always thought they were going to move back to China after earning their fortune elsewhere. As Papademetriou told me, what came before often happens again. Only now, fortune can be found at home. This departure portends the loss of a place once so integral to Chinese America that Victor Nee and Brett de Bary Nee, in their 1973 book, Longtime Californ’, noted that “virtually every Chinese living in San Francisco has something to do with Chinatown.” Two years ago, when I was on tour for my book about Chinatowns—a kind of love letter to the neighborhood that accepted my family when it first arrived in the United States—the future of these enclaves was an open question. But if China continues to boom, Chinatowns will lose their reason for being, as vital ports of entry for working-class immigrants. These workers will have better things to do than come to America.” +++

Wal-Mart and Non-Chinese Immigrants Dilute L.A.’s Chinatown

John Rogers of Associated Press wrote: “On the surface, a big Wal-Mart store might seem out of place in the midst of the old-fashioned curio shops, the little dim sum eateries and the colorful lanterns and pagodas that make up one of the oldest Chinatowns in the United States. But then so does the Catholic church that offers Sunday Masses in Croatian. Or the one that performs them in Italian. Not to mention the imposing statue of French hero Joan of Arc that stands just a stone’s throw from the one of modern China’s founding father, Sun Yat-Sen. [Source: John Rogers, Associated Press, May 20, 2012 /^]

“When Wal-Mart announced plans earlier this year to open one of its outlets on the fringes of Old Chinatown, alarm bells went off in some quarters. The local city councilman pushed successfully for a moratorium on opening large stores in downtown, although Wal-Mart got around that by pulling its permits before the ordinance took effect. Several business owners, meanwhile, expressed concerns that Wal-Mart, known for its cheap prices on everything from tires to toys, would put them out of business and lead to the destruction of the area’s ambience. /^\

“Overlooked in much of the debate was that Chinatown wasn’t always Chinatown. Over the years, it has also been Frenchtown and Little Italy, and a portion of it was once home to a Croatian community. Evidence of the latter is 102-year-old St. Anthony’s Croatian Catholic Church, located just up the hill from where the Wal-Mart would go. More recently, Chinatown’s population has seen an increase in Hispanics, who now make up about a quarter of the square-mile area’s 11,000 residents. /^\

“It’s a square mile that displays the city’s famous diversity and multicultural history to a remarkable degree, says Los Angeles writer Lisa See, who has drawn extensively from her own family’s Chinatown history for such books as “On Gold Mountain’’ and the 2009 best seller “Shanghai Girls.’’ “We as a city, I think, don’t pay much attention to that history or that diversity, but once you cover it up it’s gone for good,’’ added See, acknowledging she frets about the impact a generic Wal-Mart will have on the culturally rich area where she spent hours as a child playing in her family’s store. /^\

“Whatever the store’s impact on Chinatown, it won’t mark the first time downtown’s Chinese community has been reshaped or reinvented. Old Chinatown, as it’s now known, was actually New Chinatown when it welcomed the public on June 25, 1938, with a gala party attended by, among many others, Hollywood’s first Chinese-American movie star, Anna Mae Wong. /^\

“Often overlooked in accounts of that opening day, however, was that New Chinatown was built from the ground up to replace OId Chinatown, which was razed to make room for another LA landmark, historic Union Station. An entire neighborhood of thousands of people occupying buildings dotting more than a dozen streets was packed up and moved lock, stock and wok to the middle of what was then Little Italy and Frenchtown. /^\

“From behind the counter of K.G. Louie’s, the large curio shop his grandfather opened during that 1938 celebration, Donald Liu sees still another change coming. The younger generation of Chinese families like his, the ones that built Chinatown, are moving on to Monterey Park and several other Asian-majority suburbs just east of Los Angeles. “And I see more Hispanic folks moving in, especially at the school across the street,’’ Liu, 62, who still lives in Chinatown, said between ringing up sales on items like small jade and wood carvings and other Chinatown memorabilia for the tourists. /^\

“Across the street and down an ally known as Chung King Road still other changes are afoot. Several art galleries, some with lofts and most all featuring contemporary work by non-Asian artists, have moved onto the alley during the past 10 years. “It’s slightly turning into an artist-gentrified type of community,’’ says Eng. Not that he, Liu or others who know the area’s history are worried about its Chinese cultural heritage disappearing entirely. “I think it will remain the Chinese cultural center of Los Angeles,’’ said Liu. “Anytime there’s a demonstration or celebration, it takes place here.’’” /^\

Chinese-American in Los Angeles

The life of David Chan, an L.A. attorney whose hobby is sampling Chinese restaurants, offers an interesting perspective of a Chinese-American brought up in Los Angeles Times. Frank Shyong wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Immigration quotas then allowed just 105 Chinese into the country each year, and only 8,067 Chinese lived in Los Angeles in 1950 — less than half a percent of L.A.'s population at the time, according to census records. "Unless you lived in San Francisco, you were an oddity," said Chan, a third-generation Asian American. [Source: Frank Shyong, Los Angeles Times, April 22, 2013 /*/]

His father graduated from UCLA at the top of his accounting class, but the job offers from top firms never came. They lived in a neighborhood that real estate agents had counseled them was "accepting of Chinese," and his parents never sent him to Chinese school because they were afraid his English would suffer.” As a child, Chan hated Chinese food. The few times his parents would drag him to Chinatown restaurants like Lime House for banquets, he'd sulk over a bowl of plain rice. Home-cooked dinners were American standbys like meatloaf and spaghetti.If Chan didn't feel Chinese, it was partly by design. "I think my parents wanted to protect me," Chan said. "I was pretty much raised as an American. /*/

Like his father, Chan also attended UCLA. “At UCLA, Chan felt he was no longer an oddity. Laws passed in 1965 loosened immigration restrictions and about 9 percent of the students identified themselves as Oriental American, according to a 1971 university survey. There, Chan took a class called Orientals in America, which was the first Asian American studies course offered at UCLA. He began to read everything he could find on the subject. "It helped me recognize the fact that there weren't very many of us around. And we were discriminated against, and because of that the roads to achievement were not the same," Chan said. /*/

“After graduation, Chan took a job at a large accounting firm and befriended a group of co-workers from Hong Kong. He couldn't speak Cantonese with them, and he didn't know how to use chopsticks. But what he had in common with them was a love of Chinese food.” /*/

Story of a Chinese Immigrant in New York

Raymond Shrimp Boy Chow Describing the story of one Chinese immigrant in New York, Kirk Semple and Jeffrey E. Singer wrote in the New York Times, “The authorities were at Wang Jianhua’s door in Fujian Province, China, intent on taking his wife away. Her crime: She already had a child and she was pregnant again, in violation of the country’s one-child policy. As Mr. Wang would later recount to his friends, he stepped between the officials and his wife. A scuffle ensued, Mr. Wang’s wife escaped, and the officials hauled Mr. Wang, the son of poor rice farmers, to a jail where he was held for several days and severely beaten, his friends said.”[Source: Kirk Semple and Jeffrey E. Singer, New York Times, March 22, 2011]

“The confrontation was apparently a turning point in Mr. Wang’s life, which had already been marked by poverty and hardship. Within months, his wife still pregnant, he would set off alone for the United States with the aid of smugglers, taking a chance that a better life awaited him — and eventually his family.”

“Mr. Wang grew up in Gui’an, a rural village in a mountainous region of Fujian Province; he dropped out of school when he was about 13 to join his relatives in the rice paddies.” “He told jokes, even on the hardest days,” his older sister, Wang Wenzhen, recalled in a telephone interview from the family’s home in Gui’an. “But he was also an introverted, reserved person; didn’t share his true feelings.”

As a young man, Mr. Wang never talked about career plans, his sister told the New York Times “We are in a very backward village,” she explained. “All they can think about is making more money. What else can we dare to wish for?” She added: “I am sure he had his own dream, but he never talked about it. He knew that’s impossible.”

“His father died of a stomach ailment when Mr. Wang was 19, tipping the family deeper into poverty. Mr. Wang left home in search of better work to help support the family and, through his 20s and 30s, chased opportunities for work in Fujian Province, mostly manual labor. For several years he drove a taxi, often taking the night shift so he could help with household chores during the day and take his mother, who was chronically ill, to the hospital, Ms. Wang said.

Mr. Wang struggled not only with work but also with love. As his friends successfully found mates, married and started families, Mr. Wang, a thin man with close-set eyes and a crop of thick black hair, met failure. His sister blamed the family’s economic straits. “Nobody wanted to pick him,” she said. “Which girl would want to marry into poverty?”

When he was about 30 — old to be a bachelor by the standards of his village — he married Lin Yaofang and they had a baby, a girl. When Ms. Lin became pregnant again, in violation of the country’s one-child policy, the authorities made her get an abortion, relatives and friends said. When word of her third pregnancy reached the government, he later told friends, officials went to their house to take Ms. Lin away, leading to Mr. Wang’s detention and beating.

Chinese Immigrant Makes His Way to New York

“His decision to try his luck in New York came quietly and suddenly. He did not share his deliberations with many relatives or friends,” Semple and Singer wrote in the New York Times. “Only when he had made up his mind did he turn to the rest of the family: he needed their help raising $75,000 to pay smugglers for his passage. The task was a group undertaking, with all his closest relatives appealing for loans from everyone they knew.” Ms. Wang said she herself raised more than half the amount he needed. It took her more than a month. “You borrow $1,500 from one person, another $3,000 from another person,” she said. “One by one.” [Source: Kirk Semple and Jeffrey E. Singer, New York Times, March 22, 2011]

“Until the mid-1990s, many Chinese were smuggled into the United States in large ships, hundreds at a time. But in the face of crackdowns, smugglers began developing other methods and routes, and in recent years, officials say, most Chinese have been smuggled into the country in small groups or individually, often by way of Latin America or the Caribbean, many across the Mexican border.”

Mr. Wang set off in late January 2008, leaving behind his daughter and pregnant wife. There was no going-away party, no ceremony, his sister said. He just said goodbye and was gone. His friends and family said they did not know what route he took — he had never told them, and they had never asked.

Life and Death of a Chinese Immigrant in New York

Raymond Shrimp Boy Chow's

San Francisco tong members In March 2008, following a path carved by so many Chinese before him, Wang surfaced in New York’s Chinatown and contacted Fujianese acquaintances who were already here. ,” Semple and Singer wrote in the New York Times. “He had an immediate network to plug into. Many Fujianese have settled outside the historic core of Chinatown, west of the Bowery, clustering instead around East Broadway and north of Canal Street on the Lower East Side.”

“Mr. Wang moved into a tiny apartment on Eldridge Street on the Lower East Side with five other men, including a friend from Fujian.” the rent was $200 a month. “They slept in bunk beds and the place was loud with the constant rumble of traffic from the nearby off-ramp of the Manhattan Bridge. Mr. Wang bought a bicycle and found a job as a deliveryman at Iron Sushi, a restaurant in the Kips Bay neighborhood of Manhattan. He worked six days a week, his friends said, often in 12-hour shifts. Mr. Wang quickly fell into a grueling routine, his life pared down to its simplest components: work, eat, sleep, work, eat, sleep.”

“He ate instant oatmeal for breakfast and maybe a slice of pizza for dinner. He splurged on occasion by going to McDonald’s. He made about $500 a week, and after paying basic expenses like rent, he sent home most of whatever was left to pay his creditors and support his family, which had grown by one: his wife had given birth to a son. But he also managed to set aside enough to buy an inexpensive laptop to call his family in China at low rates on Internet telephone networks by piggybacking on a neighbor’s wireless signal.”

“The calls were apparently the highlight of his life. He called every day, usually before he went to sleep. When his family managed to get a computer, they were able to make video calls. His mother would hold up her grandson to a webcam and Mr. Wang would light up with pride, a roommate recalled. ‘say, “Daddy,” — Mr. Wang would implore his son. ‘say, “Daddy.” —

“In his spare time, Mr. Wang washed his clothes or lay in bed streaming films online — he preferred historic war movies, the roommate recalled. Their Saturday workday started an hour later than usual, so on Fridays, he and his roommates often played cards in their apartment — they preferred a Fujianese card game resembling poker — and drank red rice wine fermented locally by Fujianese store owners.”

“Then Mr. Wang discovered the inexpensive buses that traveled from Chinatown to the region’s casinos, and he started taking them on Friday nights. Mr. Wang’s friends insisted that he did not wager, but sold the free food and gambling vouchers that were included with the bus ticket and pocketed his profit, usually about $30.When asked if he had any other recreational outlets or hobbies, several of his friends laughed as if the question were preposterous.” “When can we play?” said Mr. Liu, one of his roommates, who asked that his full name not be used because of his illegal immigration status. “We can work. That’s all we do.”

“Mr. Wang’s friends and co-workers in New York said he was quiet and polite. When he talked, they said, his conversation never wandered far afield from the matters of work and money. It was his single-minded obsession, all in the service of his family and his debts, they said. “At night he talked about money worries,” Mr. Liu said, “but that’s what we all talk about.”

In March 2011, Wang was killed in a highway accident during ne of his bus trips. “The family just collapsed overnight,” Ms. Wang said after she heard the news. “My head may explode at any minute.” She said her mother fainted several times a day from crying so much. The family has not yet begun to think about how they will assume the burden of Mr. Wang’s debt. “Creditors don’t know what happened yet,” she said. “They won’t treat us nicely.” Contacted by telephone, Ms. Lin, Mr. Wang’s widow, could barely formulate sentences amid her sobs. “What can I do?” she pleaded. “Everything is a mess. And he just died.”

“Jealous” Chinese Migrant in New York Kills Mother and Four Children

In October 2013, a Chinese migrant was arrested on five counts of murder in the deaths of his cousin's wife and her four children in a stabbing rampage in their Brooklyn home. Associated Press reported: “The New York Police Department said the suspect, 25-year-old Ming Don Chen, implicated himself in the stabbings late Saturday in the Sunset Park neighborhood. Chief of Department Phil Banks said the victims "were cut and butchered with a kitchen knife." Two girls, 9-year-old Linda Zhuo and 7-year-old Amy Zhuo, were pronounced dead at the scene, along with the youngest child, 1-year-old William Zhuo. Their brother, 5-year-old Kevin Zhuo, and 37-year-old mother, Qiao Zhen Li, were taken to hospitals, where they also were pronounced dead. Chen is a cousin of the children's father and had been staying at the home for the past week or so, Banks said. [Source: Associated Press, October 27, 2013]

Bob Madden, who lives nearby, was out walking his dog when he saw a man being escorted from the building by police. He was barefoot, wearing jeans, and "he was staring, he was expressionless," Madden said. Yuan Gao, a cousin of the mother, said the man had recently moved to the area and had been staying with different people. Fire department spokesman Jim Long said emergency workers responded just before 11 pm to an emergency call from a person stabbed at the residence in Sunset Park, a working-class neighborhood of adjoining two-story brick buildings with a large Chinese community. Neighbor May Chan told the Daily News it was "heartbreaking" to learn of the deaths. "I always see (the kids) running around here," Chan said. "They run around by my garage playing. They run up and down screaming."

According to FoxNews.com: “Authorities believe Ming was jealous that his cousin’s family had been so much more successful in America than him. "The family had too much. Their income (and) lifestyle was better than his," a police source told the New York Post Sunday. The New York Police Department said Ming implicated himself in the stabbings. Chief of Department Phil Banks said the victims "were cut and butchered with a kitchen knife." The Post, citing a police source, reported that Chen showed "no remorse" as he confessed. "He made a very soft comment that since he came to this country, everybody seems to be doing better than him," Banks said. The Post reported that his last known address was in Chicago. He was unemployed after being fired from a string of restaurant jobs he couldn't hold down for more than a few weeks at a time, according to neighbors and relatives. [Source: FoxNews.com, October 28, 2013 ||||] “The children's father was not home late Saturday evening during the stabbings; he was working at a Long Island restaurant, one neighbor said. The mother tried to call him because she was alarmed about Chen's "suspicious" behavior earlier in the evening, according to Banks. When she couldn't reach her husband, Li called her mother-in-law in China, who also could not immediately reach her son. The mother-in-law then reached out to her daughter in the same Brooklyn neighborhood, Banks said.||||

“The sister-in-law and her husband went to the house at about 11 p.m. and kept banging on the door till someone answered, police said. It was Chen, "and they see that he's covered with blood," Banks said. "They don't know who this person is." The couple fled, called 911, and detectives investigating another matter nearby responded quickly, Banks said. The Post reported that Chen was arrested at the scene, barefoot and covered in blood. Neighbors said he calmly answered officers' questions as he was led into a police car and the bodies were removed from the home. However, the paper reported that Chen became violent during questioning, throwing a pair of eyeglasses at a sergeant who served as a Chinese language interpreter before kicking the table where he was cuffed and knocking the sergeant to the ground. He later punched a detective, according to the Post. ||||

“Yun Gao, a cousin of the mother, said the man had recently moved to the area and had been staying with different people. Yun said that she had met Chen in the past and described him as a "crazy" man who had failed to hold down a job as a cook. "He's lazy," Yun said Sunday. "He doesn't work too hard." ||||

Organized Crime in Chinatowns

In Chinatowns in America and Europe organized crimes is usually associated with "Tongs," community groups linked with the Chinese triads that were created in the early 20th century to help overthrow the Qing dynasty and provide support for nationalist leader Sun Yat-sen. Before 1965, exclusion laws in the U.S. made sure immigrants came from the same part of China and spoke the same dialects. This produced organized communities with close ties back home and to their community Tong.

The Tongs have traditionally extracted protection money and run vice rackets. In Chinatowns local Chinese often turned to the Tongs for justice not the local police. Books about New York Chinatown often focus on Tong wars: fierce and bloody battles between rival Tongs often fought with hatchets and knives.

The Fuk Chiang is a group that operated until recently in New York. According to an article in The New Yorker members wore black, streaked their hair and loitered around street corners in groups of three and four, usually appearing once the sun went down. Worried about shakedowns, they usually had girl friend who kept their weapons — things like knives, hammers and ice picks and occasionally guns.

Affluent Chinese Who Want to Emigrate to the United States

Jia Lynn Yang wrote in the Washington Post, Guo Hui is a Beijing resident. His “apartment was sleekly modern, with tall ceilings and children’s toys covering nearly every surface. He and his wife are educated, urban and upper-middle-class — exactly the kind of people you imagine thriving in an ascendant China. Yet they hope to move to the United States within the next few years. Their 1-year-old son was born here while they were visiting as tourists, and he has an English name, Daniel. [Source: Jia Lynn Yang, Washington Post, November 16 2012 /]

“People like me who have made money by our own efforts — we feel like we can’t make money on our own anymore,” Guo explained as we sat on his floor, watching Daniel toddle around the living room. He made his money in public relations and is an avid stock market investor. Still, he said, “people with contacts with the government can get ahead, but other people cannot.” /

“He offered an analogy to describe” China and the U.S. “Imagine two children on a playground. One has parents who are constantly hovering, making sure she doesn’t fall and scrape herself. By contrast, the other child’s parents give her more distance, letting her fend for herself. She stumbles and cries more often, but when she becomes an adult, she’s more resilient... Jimmy Wu, founder of a chemical company in Dongguan, said he wants his son to grow up in the United States, in particular because of the schools. /

“The United States is a popular destination, in part because of a program called EB5 that offers visas to people who invest at least $1 million and create at least 10 jobs here. The number of applications from China has jumped nearly ninefold since 2007, up to 2,408 last year. /

China Emigrants Returning to China

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Times, “With economies stagnant in the West and job opportunities limited, the number of students returning to China was up 40 percent in 2011 compared with the previous year. The government has also established high-profile programs to lure back Chinese scientists and academics by temporarily offering various perks and privileges. Professor Cao from Nottingham, however, says these programs have achieved less than advertised.” [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Times, October 31, 2012 +/]

“Returnees can see that they will become ordinary Chinese after five years and be in the same bad situation as their colleagues” already in China, he said. “That means that few are attracted to stay for the long run.” Many experts on migration say the numbers are in line with other countries’ experiences in the past. Taiwan and South Korea experienced huge outflows of people to the United States and other countries in the 1960s and ’70s, even as their economies were taking off. Wealth and better education created more opportunities to go abroad and many did — then, as now in China, in part because of concerns about political oppression. +/

“While those countries eventually prospered and embraced open societies, the question for many Chinese is whether the faction-ridden incoming leadership team of Xi Jinping, chosen behind closed doors, can take China to the next stage of political and economic advancement. “I’m excited to be here but I’m puzzled about the development path,” said Bruce Peng, who earned a master’s degree last year at Harvard and now runs a consulting company, Ivy Magna, in Beijing. Mr. Peng is staying in China for now, but he says many of his 100 clients have a foreign passport or would like one. Most own or manage small- and medium-size businesses, which have been squeezed by the policies favoring state enterprises. “Sometimes your own property and company situation can be very complicated,” Mr. Peng said. “Some people might want to live in a more transparent and democratic society.” +/

Bonnie Tsui wrote in The Atlantic, “Recent years have seen stories of Chinese “sea turtles”—those who are educated overseas and migrate back to China—lured by Chinese-government incentives that include financial aid, cash bonuses, tax breaks, and housing assistance. In 2008, Shi Yigong, a molecular biologist at Princeton, turned down a prestigious $10 million research grant to return to China and become the dean of life sciences at Beijing’s Tsinghua University. “My postdocs are getting great offers,” says Robert H. Austin, a physics professor at Princeton. [Source: Bonnie Tsui, The Atlantic, December 2011. Tsui is the author of “American Chinatown: A People’s History of Five Neighborhoods” +++]

“But unskilled laborers are going back, too. Labor shortages in China have led to both higher wages and more options in where they can work. The Migration Policy Institute, a Washington, D.C.–based think tank, published a paper on China’s demography through 2030 that says thinking of migration as moving in just one direction is a mistake: the flows are actually much more dynamic. “Migration, the way we understand it in the U.S., is about people coming, staying, and dying in our country. The reality is that it has never been that way,” says the institute’s president, Demetrios Papademetriou. “Historically, over 50 percent of the people who came here in the first half of the 20th century left. In the second half, the return migration slowed down to 25, 30 percent. But today, when we talk about China, what you’re actually seeing is more people going back … This may still be a trickle, in terms of our data being able to capture it—there’s always going to be a lag time of a couple of years—but with the combination of bad labor conditions in the U.S. and sustained or better conditions back in China, increasing numbers of people will go home.” +++

Between 2006 and 2010, “the number of Chinese immigrants to the U.S. has been on the decline, from a peak of 87,307 in 2006 to 70,863 in 2010. Because Chinatowns are where working-class immigrants have traditionally gathered for support, the rise of China—and the slowing of immigrant flows—all but ensures the end of Chinatowns.[Source: Bonnie Tsui, The Atlantic, December 2011. Tsui is the author of “American Chinatown: A People’s History of Five Neighborhoods” +++]

Sea Turtles

Returnees from the United States, known as ‘sea turtles,” sometimes have a hard lading a good job or getting ahead when they return to China because they are perceived as being out of touch with what’s going on in China. Those that do get jobs often find the have to work long hours for little pay. The Mandarin word for “overseas returnee” sounds like the mandarin word for ‘sea turtle.”

More than 1 million Chinese have studied in the United States, with only about a quarter of them returning home. About 42,000 students returned to China from the United States in 2006, up 21 percent from the previous year.

Some middle class Chinese who lived in the United States returned to China because they found life in the United States boring and predictable. Some ea turtles that have been away for some time find the China they have returned too to be almost unrecognizable from the China they left. One told the Washington Post, “People think in a more complicated way. I’m more straightforward now, but they’re all zigzagging.”

In a typical case a Chinese who returned to China after four years with an MBA from a good American university and fluency in English hopes to land a $40,000 information technology position but can only secure an $16,000 a year entry-level job with an insurance company. Those that can’t get any work at all are referred to as ‘sea weed.”

Chinese-Americans or Chinese who have had success in the United States have similar problems. Even those with million-dollar support and sophisticated technology and management have problems and often have to turn to relatives to help them navigate through red tape and figure out who to bribe.

Asian-Americans and Interracial Marriage

Intermarriage rates are significantly higher among Asian women than among men. About 36 percent of Asian-American women married someone of another race in 2010, compared with about 17 percent of Asian-American men.

“The term Asian, as defined by the Census Bureau, encompasses a broad group of people who trace their origins to the Far East, Southeast Asia or the Indian subcontinent, including countries like Cambodia, China, India, Japan, Korea, the Philippine Islands and Vietnam. (The Pew Research Center also included Pacific Islanders in its study.)

Asian-Americans Increasingly Choosing Asian-American Marriage Partners

Rachel L. Swarns wrote in the New York Times, “Interracial marriage rates are at an all-time high in the United States, with the percentage of couples exchanging vows across the color line more than doubling over the last 30 years. But Asian-Americans are bucking that trend, increasingly choosing their soul mates from among their own expanding community. [Source: Rachel L. Swarns, New York Times, March 30, 2012]

“From 2008 to 2010, the percentage of Asian-American newlyweds who were born in the United States and who married someone of a different race dipped by nearly 10 percent, according to a recent analysis of census data conducted by the Pew Research Center. Meanwhile, Asians are increasingly marrying other Asians, a separate study shows, with matches between the American-born and foreign-born jumping to 21 percent in 2008, up from 7 percent in 1980.

“Asian-Americans still have one of the highest interracial marriage rates in the country, with 28 percent of newlyweds choosing a non-Asian spouse in 2010, according to census data. But a surge in immigration from Asia over the last three decades has greatly increased the number of eligible bachelors and bachelorettes, giving young people many more options among Asian-Americans. It has also inspired a resurgence of interest in language and ancestral traditions among some newlyweds.

“In 2010, 10.2 million Asian immigrants were living in the United States, up from 2.2 million in 1980. Today, foreign-born Asians account for about 60 percent of the Asian-American population here, census data shows. “Immigration creates a ready pool of marriage partners,” said Daniel T. Lichter, a demographer at Cornell University who, along with Zhenchao Qian of Ohio State University, conducted the study on marriages between American-born and foreign-born Asians. “They bring their language, their culture and reinforce that culture here in the United States for the second and third generations.”

“Of course, race is only one of many factors that can come to bear in the complicated calculus of romance. And marriage trends vary among Asians of different nationalities, according to C. N. Le, a sociologist at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Dr. Le found that in 2010 Japanese-American men and women had the highest rates of intermarriage to whites while Vietnamese-American men and Indian women had the lowest rates.

Highly-Educated Chinese-Americans Finds Marital Bliss Together

Rachel L. Swarns wrote in the New York Times, “When she was a philosophy student at Harvard College eight years ago, Liane Young never thought twice about all the interracial couples who flitted across campus, arm and arm, hand in hand. Most of her Asian friends had white boyfriends or girlfriends. In her social circles, it was simply the way of the world. But today, the majority of Ms. Young’s Asian-American friends on Facebook have Asian-American husbands or wives. And Ms. Young, a Boston-born granddaughter of Chinese immigrants, is married to a Harvard medical student who loves skiing and the Pittsburgh Steelers and just happens to have been born in Fujian Province in China. [Source: Rachel L. Swarns, New York Times, March 30, 2012]

Ms. Young said she hadn’t been searching for a boyfriend with an Asian background. They met by chance at a nightclub in Boston, and she is delighted by how completely right it feels. They have taken lessons together in Cantonese (which she speaks) and Mandarin (which he speaks), and they hope to pass along those languages when they have children someday. “We want Chinese culture to be a part of our lives and our kids’ lives,” said Ms. Young, 29, an assistant professor of psychology at Boston College who married Xin Gao, 27, last year. “It’s another part of our marriage that we’re excited to tackle together.”

“Before she met Mr. Gao, Ms. Young had dated only white men, with the exception of a biracial boyfriend in college. She said she probably wouldn’t be planning to teach her children Cantonese and Mandarin if her husband had not been fluent in Mandarin. “It would be really hard,” said Ms. Young, who is most comfortable speaking in English.

“Ed Lin, 36, a marketing director in Los Angeles who was married in October, said that his wife, Lily Lin, had given him a deeper understanding of many Chinese traditions. Mrs. Lin, 32, who was born in Taiwan and grew up in New Orleans, has taught him the terms in Mandarin for his maternal and paternal grandparents, familiarized him with the red egg celebrations for newborns and elaborated on other cultural customs, like the proper way to exchange red envelopes on Chinese New Year. ‘she brings to the table a lot of small nuances that are embedded culturally,” Mr. Lin said of his wife, who has also encouraged him to serve tea to his elders and refer to older people as aunty and uncle.

Asian-American Marriage Partners Find a Cultural Bond They Couldn’t Find with White

Wendy Wang, the author of the Pew report, said that demographers have yet to conduct detailed surveys or interviews of newlyweds to help explain the recent dip in interracial marriages among native-born Asians. (Statistics show that the rate of interracial marriage among Asians has been declining since 1980.) But in interviews, several couples said that sharing their lives with someone who had a similar background played a significant role in their decision to marry.

It is a feeling that has come as something of a surprise to some young Asian-American women who had grown so comfortable with interracial dating that they began to assume that they would end up with white husbands. Chau Le, 33, a Vietnamese-American lawyer who lives in Boston, said that by the time she received her master’s degree at Oxford University in 2004, her parents had given up hope that she would marry a Vietnamese man. It wasn’t that she was turning down Asian-American suitors; those dates simply never led to anything more serious.Ms. Le said she was a bit wary of Asian-American men who wanted their wives to handle all the cooking, child rearing and household chores. “At some point in time, I guess I thought it was unlikely,” she said. “My dating statistics didn’t look like I would end up marrying an Asian guy.”

“But somewhere along the way, Ms. Le began thinking that she needed to meet someone slightly more attuned to her cultural sensibilities. That moment might have occurred on the weekend she brought a white boyfriend home to meet her parents. Ms. Le is a gregarious, ambitious corporate lawyer, but in her parents’ home, she said, “There’s a switch that you flip.” In their presence, she is demure. She looks down when she speaks, to demonstrate her respect for her mother and father. She pours their tea, slices their fruit and serves their meals, handing them dishes with both hands. Her white boyfriend, she said, was “weirded out” by it all. “I didn’t like that he thought that was weird,” she said. “That’s my role in the family. As I grew older, I realized a white guy was much less likely to understand that.”

“In fall 2010, she became engaged to Neil Vaishnav, an Indian-American lawyer who was born in the United States to immigrant parents, just as she was. They agreed that husbands and wives should be equal partners in the home, and they share a sense of humor that veers toward wackiness. (He encourages her out-of-tune singing and high kicks in karaoke bars.) But they also revere their family traditions of cherishing their elders.

“Mr. Vaishnav, 30, knew instinctively that he should not kiss her in front of her parents or address them by their first names. “He has the same amount of respect and deference towards my family that I do,” said Ms. Le, who is planning a September wedding that is to combine Indian and Vietnamese traditions. “I didn’t have to say, “Oh, this is how I am in my family.” “

Ann Liu, 33, a Taiwanese-American human resources coordinator in San Francisco, had a similar experience. She never imagined that an Asian-American husband was in the cards. Because she had never dated an Asian man before, her friends tried to discourage Stephen Arboleda, a Filipino-American engineer, when he asked whether she was single. ‘she only dates white guys,” they warned. But Mr. Arboleda, 33, was undeterred. “I’m going to change that,” he told them.

“By then, Ms. Liu was ready for a change. She said she had grown increasingly uncomfortable with dating white men who dated only Asian-American women. “It’s like they have an Asian fetish,” she said. “I felt like I was more like this “concept.” They couldn’t really understand me as a person completely.” Mr. Arboleda was different. He has a sprawling extended family — and calls his older relatives aunty and uncle — just as she does. And he didn’t blink when she mentioned that she thought that her parents might live with her someday, a tradition among some Asian-American families.

“At their October wedding in San Francisco, Ms. Liu changed from a sleek, sleeveless white wedding gown into the red, silk Chinese dress called the qipao. Several of Mr. Arboleda’s older relatives wore the white, Filipino dress shirts known as the barong. “There was this bond that I had never experienced before in my dating world,” she said. “It instantly worked. And that’s part of the reason I married him.”

Image Sources: Tales of Shanghai, University of Washington; Shrimp boy picture San Francisco Examiner

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2022