XIBE

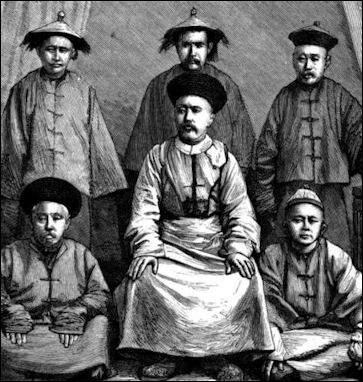

Xibe military colonists

The Xibe are an ethnic group that lives along the Ili River in Xinjiang and in Liaoning Province. Also known as the Sibe, they speak a Manchu-Tungus language and are regarded as the last speakers of Manchu, the language of the Manchu emperors who ruled China during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). The Xibe are also famous for their riding and archery skills. They group has produced many excellent archers. The Xibe have traditionally practiced shamanism, ancestor worship Tibetan Buddhism.

The Xibe (pronounced SHEE-ba) are descendants of a Manchu garrison from northeast China brought to western China in the 18th century to protect the Chinese and help them colonize the western frontier. The Xibe soldiers brought along their wives, who gave birth to 300 babies in the year-long trek from Manchuria in eastern China. Ironically the Xibe that moved to west retained their traditional customs and language while those that remained behind in northeast China intermixed with local Han people and lost their language and customs. Xibe is "Siwe" in their oral language and "Sibe" in the written language.

Xibe are the 31st largest ethnic group and the 30th largest minority out of 55 in China. They numbered 190,481 in 2010 and made up 0.01 percent of the total population of China in 2010 according to the 2010 Chinese census. Xibe population in China in the past: 189,357 in 2000 according to the 2000 Chinese census; 172,847 in 1990 according to the 1990 Chinese census. A total of 19,022 were counted in 1953; 33,438 were counted in 1964; and 77,560 were, in 1982. They live in Qapqal Xibe Autonomous County (Chabuhar Xi Bo autonomous county), Yili district, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region and to a lesser extent in Liaoning and Jilin provinces. [Sources: People’s Republic of China censuses, Wikipedia]

There are two main Xibe groups: the one still living in Liaoning Province, and the other in Xinjiang Province along the Ili River. The two Xibe groups have assimilated to Han Chinese cultures at greatly different rates: the Xinjiang Xibe have been culturally more conservative than have the Northeast Xibe. The Xinjiang groups are also influenced by large neighboring groups such as the Uigur and Kazak. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

See Separate Articles MANCHUS: IDENTITY, RELIGION AND LANGUAGE factsanddetails.com ; MANCHU CULTURE AND LIFE factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:“The Manchus” by Pamela Kyle Crossley Amazon.com; “China's Last Empire: The Great Qing” by William T. Rowe and Timothy Brook Amazon.com; “The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China by Mark C. Elliott Amazon.com; “Familiar Strangers: A History of Muslims in Northwest China”by Jonathan N. Lipman Amazon.com; “Securing China's Northwest Frontier” by David Tobin” Amazon.com; “Ethnic Minorities of China” by Xu Ying & Wang Baoqin Amazon.com; “Handbook on Ethnic Minorities in China” by Xiaowei Zang Amazon.com; “China's Ethnic Minorities” by Xiao Xiaoming Amazon.com;

Xibe History

The Xibe attribute their ancestry to the ancient Xianbei people, though there is no hard evidence to support this contention. The ancient Xianbei people, a branch of the ancient Donghu ethnic group, a Manchu-Mongolian group in northern China. Originally, the Xianbei engaged in hunting and fishing and lived a nomadic life on the east side of the Daxing'anling Mountains near the Russian border in northeast China. The Xianbei roamed as nomads over vast areas between the eastern slopes of the Great Xinggan Mountains in northeast China.

Duanjibu, a senior Manchu commander who fought in the decisive Battle of Qurman (1758)

In A.D. 89, the northern Xiongnus, defeated by the Han Dynasty troops, moved westward, abandoning their land to the Xianbeis. Between A.D. 158 and 167, the Xianbei people formed a powerful tribal alliance under chieftain Tan Shihuai. Between the third and sixth centuries, the Murong, Tuoba, Yuwen and other powerful tribes of Xianbei established political regimes in the Yellow River valley, where they mixed with Han people. But a small number of Xianbeis never strayed very far from their native land along the Chuoer, Nenjiang and Songhua rivers. They were probably the ancestors of the Xibe people. [Source: China.org |]

At the time of the Mongol invasion, the Xibe were hunters and fishers living in the far northeastern portion of China. Before Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), the Xibe people lived in a vast area centering on Fuyu County in Jilin Province and reaching as far as Jilin in the east, Hulunbuir in the west, the Nenjiang River in the north and the Liaohe River in the south. In 1593 the ethnic name "Xibe" appeared in the historic records. In the 16th century, the Manchu nobility rose to power. In order to expand their territory and consolidate their rule, the Manchu rulers repeatedly tried to conquer neighboring tribes by offering them money, high position and marriage, and more often by armed force. Various Xibe tribes submitted themselves one after another to the authority of the Manchu rulers.By the late sixteenth century, they had come under the domination of the Manchu leader Nurhachi.; at this time their social structure and life changed as they became settled farmers.

In the Qing Dynasty (1616-1911) the Xibe were incorporated into the "Eight banners" of "Mongolia" and "Manchu". According to the "eight-banner system," soldiers in the banners worked the land in time of peace and went to battles during wartime, shouldering heavy military and labor services. Many Xibe were moved by the Qing court to Yunnan in southwestern China and Xinjiang in northwestern China. In the late seventeenth century, the Qing government moved many Xibe military and civilians to the frontiers, to larger Liaoning cities, and to Beijing. The Qing court also gave different treatment to various Xibe tribes according to the time and way of their submission to show varying degrees of favor and create differences in classification among them. |

In the middle of 18th century, Qing dynasty relocated some Xibe army and their families to Xinjiang in order to reinforce Northwestern frontier defense. In 1764, 5,000 Xibe troops and their families were sent to Xinjiang to control the recently defeated Jungars, and this accounts for the present-day population of Xibe in the far northwest.Those Xibe people settled in Yili valley and built their second homeland while defending the frontier and cultivating the land there. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences; “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994 |~|]

See Separate Article: HISTORY OF THE MANCHUS —THE RULERS OF THE QING DYNASTY factsanddetails.com

Great Western Relocation of the Xibe

This where the most assimilated Xibe live in northeast China; the others are in Xinjiang in the west. See Qapqal Xibe Autonomous County Below

During the reign of the Qianlong Emperor in the Qing Danasty, the Qing government repressed the Amursana, old Hezhuomu and young Hezhuomu rebellions in northwest China. Afterwards the Yili district of present-day Xinjiang was in such a bad state and was so sparsely populated it was easy pickings for Russian invaders. To address this problem, the Qing leadership dispatched military units from southern Xinjiang to defend Yili but were unable to get enough soldiers to do the job. To address this problem, 1020 Xibe soldiers and officers were relocated from Shenyang, Fengchen, Liaoyang, Fushun and Jingzhou in northeastern China, with 3275 family members,to Yili, Xingjing in two batches. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences ~]

Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times: Loyal to the core and prized for their horsemanship, several thousand Manchu soldiers heeded the emperor’s call and, with families and livestock in tow, embarked in 1764 on a trek that took them from northeastern China to the most distant fringes of the Qing dynasty empire, the Central Asian lands now known as Xinjiang. It was an arduous, 18-month journey, but there was one consolation: After completing their mission of pacifying the western frontier, the troops would be allowed to take their families home. “They were terribly homesick here and dreamed of one day going back east,” said Tong Hao, 56, a descendant of the settlers, from the Xibe branch of the Manchus, who arrived here emaciated and exhausted. “But sadly, it was not to be.” [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, January 11, 2016]

The garrisoning assignment was supposed to last 60 years. At first, 1,016 Xibe officers and soldiers were dispatched, and they took along more than 2,000 family members. The Xibe left their northeastern homeland in oxcarts. They crossed passed Mongolian plateau and Altai Mountains into Xinjiang. According to the Chinese government: In one year and five months, the poorly-equipped Xibes scaled mountains and forded rivers, eating in the wind and sleeping in the dew, trekking across deserts and grasslands in Mongolia to the faraway northwestern border. With striking stamina and tenacity, they endured starvation, drought, diseases and difficulties brought about by Qing officials, big and small, who embezzled army provisions and goaded them on. This was how the Xibes came to live far apart in northeast and northwest China. The heavy toll taken by the trip sharply reduced the originally small Xibe population. |

The first group of Xibe soldiers and officers departed on the 10th day of the forth lunar month (4:10) in 1764, Calender); the second group departed on the 19th day of the forth lunar month (4:19). The day before the second group left (on 4.18), family of the migrating Xibe gathered at Shenyang Xibe family temple ("Taiping temple") to give a farewell dinner for their relocating relatives.

Re-enacting the suffering of the journey west

Events commemorating the migration have traditionally begun on this and the "Western Relocation Festival” that honors the migration gradually came into being. They reached Yili in the seventh lunar month (7.20 and 7:21) in 1765 at Tachen and Bortala. During the 10000-li journey, the Xibe soldiers and their families overcame many difficulties to succeed at their historic feat. The whole journey took one year and four months and was way ahead of the three years it schedule to take. ~

The great journey is described in “Song of Western Relocating:

Passing the trials of a long journey through the thorns,

Experiencing sorts of tribulation of wind and rain,

man and woman, no matter young and old,

followed the stout ox to climb western steep mountains

Building bridges and exploit the flat road;

With steel like foot,

To plod thorns and conquer difficulties. ~

Early Xibe Social and Economic Development

The ancient Xibe people lived by fishing and hunting generation after generation. By the mid-16th century, the social organizations of the Xibe ethnic group had shifted from blood relationship to geographical relationship. The internal links in the paternal blood relation groups became very loose. In each Xibe village lived members with different surnames. Because of the low productivity, collective efforts were required in hunting and fishing. Members of the same village maintained relatively close links in productive labor, and basically abided by the principle of joint labor and equal distribution. By the mid-17th century, the "eight-banner system" had not only brought the Xibe people under the reign of the Qing Court, but also caused drastic changes in their economic life and social structure. [Source: China.org |]

The Xibes are a hard-working and courageous people. Although geographical isolation has given rise to certain differences between the Xibes in northeast and northwest China in the course of history, they have all made contributions to developing and defending China's border areas. The Xibes in Xinjiang in particular have made great contribution to the development of farming and water conservancy in the Ili and Tacheng areas. Since the Qing court stopped supplying provisions to the Xibes after they reached Xinjiang, they had to reclaim wasteland and cut irrigation ditches without the help of the government. They first repaired an old canal and reclaimed 667 hectares of land. With the increase of population, the land became insufficient. |

Despite such difficulties as lack of grain and seeds and repeated natural disasters, the Xibe people were determined to turn the wasteland on the south bank of the Ili River into farmland to support themselves and benefit future generations. After many failures and setbacks, they succeeded in 1802 after six years of hard work in cutting on mountain cliffs a 200-km irrigation channel to draw water from the Ili River. With the completion of this project, several Xibe communities settled along the channel. Later, the Xibe people constructed another canal to draw water from the upper reaches of the Ili River in the mid-19th century. In the 1870s, they cut two more irrigation channels, obtaining enough water for large-scale reclamation and farming. The local Kazak and Mongolian people learned a lot of farming techniques from the Xibes. |

Great Chabuchar (Qapqal) Canal

The northwestern frontier of China is mostly dry and made up of windy deserts, steppe and mountains. The hardworking and strong Xibe people built a canal and dyke system through the mountains to deliver water to make the desert bloom. The famous 100-kilometer-long Great "Chabuchar" Canal transports water from Yili River to fields that grow grapes, melons and various fruits, vegetable and grains.

map of the Xibe Yili military complex in 1809

After the Xibe moved to Xinjiang it son became clear that existing wells could not provide enough water to support the cultivated fields need to provide food for the Xibe population. The situation drew the attention of general director Tuberte. He inspected the upstream part of the Yili River the terrain between it and the Xibe’s adopted home on Chabuchar Plain and, with the help of others, devised a blue print of digging the "Great Chabuchar Canal" (Qapcal Canal), utilizing Yili River to irrigate Chabuchar farmland, [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

After receiving approval from General Yili, Director Tuberte created to great workforces to build the canal in 1801, 36 years after the Xibe migrated to Xinjiang. By 1808, a great canal four meter high, three meter deep and 100 kilometers long had been built up after sevens years of hardship and struggling. Like a giant dragon, the canal irrigate the around arid field. In order to memorialize Director Tuberte, the Xibe built two "Director Tuberte Temple" at the canals entrance at Dalongko and Qiniulu. During its dedication ceremony, the great canal was named "Chabuchar Buha", which means "Great Canal of Granary" in the Xibe language. The Great Chabuchar Canal not only help the Xibe put down their roots in the Yili region it provided an example of how to develop the harsh western frontier in Xinjiang with projects like the "Shartang Canal" and "Tarqi New Canal". ~

Xibe Efforts to Defend the Motherland

While building irrigation channels and opening up wasteland, the Xibes also joined soldiers from other ethnic groups in guarding the northwestern border. In the 1820s, more than 800 Xibe officers and soldiers fought alongside Qing government troops on a punitive expedition against rebels backed by British colonialists. In a decisive battle they wiped out the enemy forces and captured the rebel chief. In 1876, the Qing government decided to recover Xinjiang from the Tsarist Russian invaders. The Xibes stored up army provisions in preparation for the expedition despite difficulties in life and production inflicted by the marauders and cooperated with the Qing troops in mopping up the Russian colonialists south of the Tianshan Mountain and recapturing Ili. [Source: China.org |*]

By relocating the soldiers not only protected and develop the frontier, they conserved the traditional Manchu language. While they Xibe tribe back in their homeland were assimilated by the Han Chinese. Mongols and Manchus, the Xibe in Xinjiang kept alive their Manchu language and culture in part because there were few people where they lived to influence them. ~

Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times: “Even as intermarriage and migration to other parts of the country dilute their identity, the Xibe remain proud of their history and especially their role helping to secure the lands that greatly expanded China’s borders. It was a Manchu emperor who tapped the Xibe to settle the Ili Valley here after Qing soldiers massacred or exiled the nomads who had long menaced the empire’s western borderlands.

“In the decades that followed, a succession of rebellions, many of them led by the region’s ethnic Uyghurs, kept the Xibe garrisons busy and sometimes thinned their ranks. One battle in 1867 nearly halved the Xibe population, to 13,000. Until the 1970s, the Xibe remained isolated from the ethnic Kazakhs and Uyghurs who settled Ghulja, a city that sits on the far side of the Ili River. The Xibe also ate pork and practiced a blend of shamanism and Buddhism, making intermarriage with the Muslim Kazakhs and Uyghurs relatively rare. “We happily lived in our own world and rarely took boats to the other side of the river,” said Tong Zhixian, 61, a retired forestry official who sings and performs traditional Xibe dances at the county’s new history museum. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, January 11, 2016]

Xibe-Daur Congress in 1947, two years before the Communist takeover of China

Xibe and the Communist Revolution

The Xibe people in Xinjiang staged an uprising in support of the Revolution of 1911 soon after it broke out. Those in northeast China joined the Han and Manchu people in anti-Japanese activities after that part of the country fell under Japanese rule in 1931. Many Xibes joined such patriotic forces as the Anti-Japanese Allied Forces, the Army of Volunteers and the Broad Sword Society. Quite a few Xibes joined the Chinese Communist Party and the Communist Youth League to fight for national liberation. In September 1944, struggle against Kuomintang rule broke out in the Ili, Tacheng, Altaic areas in Xinjiang. The Xibes there formed their own armed forces and fought along with other insurgents.

According to the Chinese government: Before 1949, the feudal relations of production in Xibe society emerged and developed with the incorporation of the Xibes into the "Eight Banners" of the Manchus, under which the banner's land was owned "publicly" and managed by the banner office. Irrigated land was mostly distributed among Banner officers and soldiers in armor according to their ranks as their emolument. The rest was leased to peasants. This system of distribution from the very beginning deprived the Xibe people of the irrigated land which they had opened up with blood and sweat. [Source: China.org |]

“In the 1880s, the "banner land system" for the Xibe people in northeast China began to collapse, and the banner land quickly fell under the control of a few landlords. Although the banner system stipulated that the banner land could not be bought or sold, cruel feudal exploitation gradually reduced the Xibe people to dire poverty and deprived them of their land, and an increasing number of them became farmhands and tenants, leading a very miserable life.” |

The founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 ushered in era for the Xibe people. In March 1954, the Qapqal Xibe Autonomous County was established on the site of Ningxi County in Xinjiang, where the Xibe people live in compact communities. “Since 1949, a series of social reforms have been carried out in the Xibe areas. Industrial and agricultural production has grown tremendously and people's living standards have gone up accordingly. The economic and cultural leaps in the Qapqal Autonomous County are a measure of the great success the Xibe people have achieved. |

“As a result of their hard work, grain output in the county in 1981 was nearly four times the pre-liberation average, and the number of cattle three times as big. Small industrial enterprises including coal mines, farm machinery works, fur and food processing mills, which were non-existent before, have been built for the benefit of people's life. There are in the county 12 middle schools and 62 primary schools enrolling 91.3 per cent of the children. The Xibe people have always been more developed educationally. Many Xibe intellectuals know several languages and work as teachers, translators and publishers. Horse riding and archery are two favorite sports among the Xibe people. Since 1949, endemic diseases with a high mortality rate such as the Qapqal disease have been stamped out, and the population of the Xibe has been on the increase.” |

Xibe Languages

Xibe written language

The Xibe still speak and write in their old language whose written form was developed in the 17th century out of Manchu. The Xibe language belongs to the Manchu division of the Manchu-Tungusic branch of the Altaic Language Family. However, those living in northeastern China mostly speak Chinese. Xibe writing is based on the modified Manchu writing, which is in turn is based on Mongolian writing.

Legend has it that the Xibe ethnic group once had its own script but has lost it after the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) was founded. A growing number of Xibe people came to learn the Manchu and Han languages, the latter being more widely used. In Xinjiang, however, some Xibe people know both the Uygur and Kazak languages. In 1947, certain Xibe intellectuals reformed the Manchu language they were using by dropping some phonetic symbols and adding new letters of the Xibe language. This Xibe script has been used as an official language by the organs of power in the autonomous areas. [Source: China.org |*]

Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times: “The Xibe language has gradually evolved from Manchu as it absorbed vocabulary from the Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Mongolians and even the Russians who passed through Xinjiang. Unlike Mandarin, which has few borrowed words, Xibe is flecked with adopted nouns like pomodoro (tomato), mashina (sewing machine) and alma (the Uyghur word for apple). Scholars say that the phonetic diversity of Xibe, a language thought to be related to Turkish, Mongolian and Korean, allows speakers to easily produce the sounds of other tongues. “We fought with the other groups, but there were so few of us here and no one else spoke our language, so we had to learn theirs to survive,” said Mr. Tong, an engineer at the county power company who is vice president of the Xibe Westward March Culture Study Association, a local group that promotes Xibe language and history. “That’s why we are so good at learning foreign languages.” [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, January 11, 2016]

See Separate Articles MANCHUS: IDENTITY, RELIGION AND LANGUAGE factsanddetails.com

Benefits of the Xibe Language Speakers

Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times:“ Xibe have proved to be an ethnographic curiosity and a linguistic bonanza. As the last handful of Manchu speakers in northeast China have died, the Xibe have become the sole inheritors of what was once the official tongue of one of the world’s most powerful empires, a domain that stretched from India to Russia and formed the geographic foundation for modern China. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, January 11, 2016]

“In the decades after the revolution in 1911 that drove the Qing from power after nearly 300 years, Mandarin Chinese vanquished the Manchu language, even in its former stronghold in the forested northeast. But the isolation of the Xibe in this parched, far-flung region near the Kazakh border helped keep the language alive, even if its existence was largely forgotten until the 1940s.

“In the decades after the revolution in 1911 that drove the Qing from power after nearly 300 years, Mandarin Chinese vanquished the Manchu language, even in its former stronghold in the forested northeast. But the isolation of the Xibe in this parched, far-flung region near the Kazakh border helped keep the language alive, even if its existence was largely forgotten until the 1940s.

“For scholars of Manchu, especially those eager to translate the mounds of Qing dynasty documents that fill archives across China, the discovery of so many living Manchu speakers has been a godsend. “Imagine if you studied the classics and went to Rome, spoke Latin and found that people there understood you,” said Mark C. Elliott, a Manchu expert at Harvard University who said he remembered his first encounter, in 2009, with an older Xibe man on the streets of Qapqal County. “I asked the guy in Manchu where the old city wall was, and he didn’t blink. It was a wonderful encounter, one that I’ll never forget.”

“Those linguistic talents have long been an asset to China’s leaders. In the 1940s, young Xibe were sent north to study Russian, and they later served as interpreters for the newly victorious Communists. In recent years, the government has brought Xibe speakers to Beijing to help decipher the sprawling Qing archives, many of them of imperial correspondence that few scholars could read. “If you know Xibe, it takes no time for you to crack the Qing documents,” said Zhao Zhiqiang, 58, one of six students from Qapqal County sent to the capital in 1975, and who now heads the Manchu study department at the Beijing Academy of Social Sciences. “It’s like a golden key that opens the door to the Qing dynasty.”

Trying to Keep the Machu and Culture Alive

The 35,000 or Xibe that live in Chapchal County in Xinjiang remain proud of their Manchu traditions and have worked hard to keep their language alive. They have own broadcasting station, weekly newspaper and Chinese-language website. Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times:“Despite the local government’s best efforts, which include language instruction in primary schools and the financing of a biweekly newspaper, what is known here as Xibe is facing the common fate of many of the world’s languages: declining numbers of speakers and the prospect of extinction. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times, January 11, 2016]

“Although many young people here still speak Xibe at home, few of them can read its graphically bold script, made up of 121 letters and written vertically, from left to right. One recent day in the offices of The Qapqal News, a four-page gazette composed mostly of articles translated from the state-run news media, He Wenjun, 72, a teacher and translator, said he worried that his children and grandchildren could not read or write Xibe. “Language is not only a tool for communication, but it ties us to who we are and makes us feel close to one another,” said Mr. He, who has spent decades translating imperial Qing documents into Chinese. “I wonder how much longer our mother tongue can survive.”

“But generous government funding might not be enough to save the language of the Manchus. At the county museum here, a sprawling collection of dioramas depicting the westward exodus, Mr. Tong spends most days performing to an empty room. After one recent performance, an ensemble piece that featured Xibe matrons twirling with very large knives, he wondered aloud whether he might be the last of his generation to keep such traditions alive. “Young people just aren’t interested in this kind of thing,” he said, wiping the sweat from his brow. “Sure, they might study some Xibe in school, but once they leave the classroom, they plunge right back into Mandarin.”

Xibe Religion and Festivals

Xibe archery class

The Xibe have traditionally practiced shamanism, ancestor worship and Tibetan Buddhism. The Xibe honor a pantheon of gods that includes the Insect King, Dragon King, Earth Spirit and Smallpox Spirit. The have some unique funerary customs, and especially to Xilimama (who maintains domestic tranquility) and to Hairkan (who protects livestock). In addition, there were Xibe shamans. Some Xibe people are followers of Buddhism. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

Xibe funerary traditions are unique. Most bodies are interred. Those of shaman, girls, women who died at childbirth and people who committed suicide by hanging themselves are cremated. The girls ashes are scattered. Those of the others are kept in urns. In addition, husband and wife must be disposed of in a like manner. Thus, the wife of a shaman must be cremated; if she dies first, her body is buried until her husband dies, and then is exhumed and cremated. |~|

Xibe festivals include the Spring Festival and "4.18" Western Relocating Festival ( Western Exodus Festival, April 18th Festival) in which they show off their skill as archers. The Xibe people are pious worshippers of ancestors, to whom they offer fish every March and melons every July. Black Ash Day (16th day of the first lunar month) is celebrated by people wearing cloth blackened by the ash from the bottom of the pan and applied to each other's face to pray for a harvest and pray to the corn god for free the plants of all the calamities.

The "4.18" Western Relocating Festival commemorates the date April 18th, 1764, when 3,275 Xibes were forced to relocate from Shenyang in northeastern China to Xinjiang in northwestern China to serve as reserve soldiers at a military outpost. On this day, Xibe people gather to hold activities like wrestling, shooting arrows and horse racing. [Source: Chinatravel.com]

Xibe Life, Housing and Clothes

In Xinjiang, Xibe live in walled villages with between 100 and 200 houses. The enclosing wall can be two or three miles long. Most houses have a courtyard a central room with a stove and heated kangs for sleeping in the winter. A Xibe house usually consists of three to five rooms with a courtyard, in which flowers and fruit trees are planted. The gates of the houses mostly face south. The Xinjiang Xibe live in a relatively good area for herding and agriculture and raise wet rice, cotton and fruits with irrigation. There are also skilled at making embroidered slippers.

The Xibe people in northeast and northwest China have each formed their own characteristics in the course of development. The language and eating, dressing and living habits of the Xibes in the northeast are close to those of the local Han and Manchu people. Living in more compact communities, those in Xinjiang have preserved more of the characteristics of their language script and life styles.[Source: China.org |]

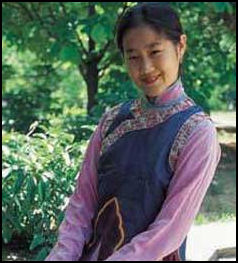

In terms of clothing, the Xibe women in Xinjiang like close-fitting long gowns reaching the instep. Their front, lower hem and sleeves are trimmed with laces. Men wear short jackets with buttons down the front, with the trousers tightly tied around the ankle. They wear long robes in winter. The Xibe costume in northeastern China is basically the same as that of the Han people.

Xibe Society, Customs and Taboos

Xibe family

According to the “Encyclopedia of World Cultures”: ““The Xibe are patrilineal, as are most in China's northeast. The hala (phratry) consists of people having the same patronym. Each hala has several mokon (local patrilineages the members of which can trace descent from a common ancestor). Xibe societal organization, however, has been changing to a territorial system. The new system is one of gashan (groups whose members live together to work together). Among the Northeast Xibe, hunting gashan are formed; among the Xinjiang Xibe, farming and irrigation-work gashans are favored. [Source: “Encyclopedia of World Cultures Volume 6: Russia-Eurasia/China” edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond, 1994]

According to the Chinese government: In the past, each Xibe family used to consist of three generations, sometimes as many as four or five generations, being influenced by the feudal system. Marriage was, in most cases, decided by parents. Women held a very low status and had no right to inherit property. The family was governed by the most senior member who had great authority. When the father was living, the sons were not allowed to break up the family and live apart. In family life, the old and the young each had his position according to a strict order of importance, and they paid attention to etiquette. "Hala," a council formed by male clan heads, handled major issues within the clans and enforced clan rules.” |

According to Chinatravel.com: “The Xibe pay their respect and give way to the elderly when they meet them. People of the same generation greet each other when they meet. When a guest arrives, the daughter-in-law of the host family will offer cigarettes and serve tea to him. If the guest is of same generation with her, he should stand up or raise himself slightly and accept the cigarette or tea with both hands. When seeing off the guest, the whole family will accompany him to the gate. [Source: Chinatravel.com \=/]

Xibe taboos include eating dog meat, wearing dogskin ware, sitting on or striding over clothes, hats, quilts or pillows—the same as Manchu people. Other taboos are putting trousers, shoes or socks that have been worn on a high place, sitting on or stepping on kitchen ranges, sitting on or standing on the threshold, whistling in the house and knocking at the dinner table or dishware with chopsticks. Guests should not enter those houses with a piece of red cloth or a bunch of grass at the gate because there may be a patient or lying-in woman and strangers are not allowed to enter the house.

Xibe Food and the "Whole Sheep Banquet"

Rice and flour are their staple food. In the past they mostly ate husked kaoliang (Chinese sorghum). Those living in Xinjiang also eat rice cooked with mutton, carrots, and raisins with their hands. They also like tea with milk, milk, butter and other dairy products. On the 18th of the forth lunar month is a major Xibe festival. People eat flour or bean sauce on this day to mark the successful conclusion of their ancestors' westward move. In autumn, they pickle cabbage, leek, carrot, celery and hot pepper. The Xibes enjoy hunting and fishing during the slack farming season. They also cure fish for winter use. |

Qapqal Xibe Autonomous County in pink in Xinjiang

Xibe food varies depending on where the Xibe live. Wheat and rice are the staples for those living in Xinjiang. In addition to "leaven dough cake" bread and milk tea, they are also fond of leek hezhi (a sort of dumpling), pumpkin steamed jiaozhi, Uyghur "grasping rice" and "naren"(meat and fried dough flake). In winter, they enjoy " Wuta tea" (greasing tea). Every family raises poultry and livestock and plants all sorts of vegetables.

A special flour sauce used as a regular dish condiment is boiled and prepared during the "Western Relocation Festival” in the forth lunar month and stored in special crocks. At the end of autumn, cucumbers are pickled with slices of leek, green pepper, carrot, cabbage and celery to make the "hua hua dish" which is eaten in the winter and spring. Xibe living in northeastern China eat sorghum, rice, corn and wheat as their staples. Among the most famous Xibe dishes are "fish soup and sorghum grain", "blood and pork", "whole steamed piglet", "chafing dish" and "pumpkin steamed jiaozhi". "Whole sheep banquet"—made of sweetbread and other internal organs from sheep— is the most characteristic Xibe dish. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

The Xibe language name for "Whole sheep banquet" means "dishes held by bowls". Fresh sheep organs and body parts such as the heart, liver, lung intestine, kidney, tongue, eye, ear, stomach, foot and blood are the basic cooking material. Each body part is chopped to make a 16 dishes. Some have caraway seeds and shallot added for flavoring. Dishes made of intestines have many styles. To make sausages clean intestines are filled with sheep blood, liver, sheep fat, onion, meat chipping, seasoning and rice. Each dish requires its own special procedure to make. Pickled vegetables are served as side dishes. According to custom of The Xibe, only extremely honored guests are served the "whole sheep banquet" because it is so difficult to make.

Xibe Music, Novels and Dance

Xibe women are good at paper cutting, and windows are often decorated with beautiful paper-cuts. The Xibes are adept at singing and dancing. They are especially good at playing Dongbuer, a plucked musical instrument. They also play Maken, their harmonica.|

The "Dongbur" is the traditional stringed instrument of The Xibe in Qapqal Xibe Autonomous County, Huochen and Huamu, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. The instrument’s head and neck are made of wood and similar to "san xuan", a Han Chinese stringed instrument. The pear-shaped body is made of red pine or birch. The instrument has two strings, which are made of goat intestine. The tone of the instrument is low and moving. It is mainly uses to accompany dancing and play 10 famous melodies. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities ~]

The word for dancing in the Xibe language is "Beilun". The types of Xibe dancing are diverse. At present, traditional folk dances popular in Chabuchar include Xibe benlun, Arshur, clapping dance, saluting dance, drunk dance, butterfly dance, dung collecting dance, galloping dance, and threshing dance. Most of Xibe dances are solo dances or pair dances for a man and woman. They have been described as “brief but brave, flexible and magnificent.” Generally, they are divided into robust and delicate types. Robust types are suitable for men. They have a straightforward, strong and humorous character. The delicate women’s type dances highlight lightness, elegance and flexibility.

Many Xibe dances have their roots in activities from daily life. For example, the galloping dance imitates a running horse and the rider's vigorous bearing and the arrow shooting skill of the Xibe. The Saluting dance consists of bowing and courtesy activities. The drunken dance displays various kinds of drunken behavior seen at harvesting ceremonies and other festivals. The Butterfly dance mimic the butterfly catching process. It shows the love of young men seeking women.

See Xinjiang-Set Fiction by Jueluo Kanglin Under KAZAKH AND KYRGYZ HORSEMEN AND NOMADS IN XINJIANG factsanddetails.com

Xibe Archery

The Xibe people are good at horseback riding and arrow shooting. The bow and arrow have traditionally held high positions in Xibe daily life. As a tool and weapon, they have have always been at the Xibe’s side. People have used them to defend themselves against enemies as well as hunt and fish. Thomas Allen in National Geographic. "When a girl is born, the family hangs a red banner at the door. When a boy is born, neighbors see an archers bow. At a sports field in Xibe country. I watched a coach scowling when arrows hit nearly near the bull's-eye. he said he was working his archers — boys and girls — eight hours a day, six days a week, taking aim at the next Olympics."

According to tradition, when a Xibe boys is born his family hang a little bow and a little arrow on their gates. When a boy grows up to 5 or 6 years old, his parents make bow and arrow for him and train him to use it. When boys are 15 or 16 years old, they are organized into groups based on where they live. They practice at dawn and dusk each day, with coaches directing them. All young men undergo a strict examination of riding and shooting when they are 18 years old. Those who pass the examination are registered as "Armoured" and enjoy the superior prestige. Those who fail are called "idle" and they viewed with contempt. Being a skilled archer is prerequisite to being a Xibe man. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities]

In Xibe areas, each village has an arrow shooting range and each family owns bows and arrows. Arrow shooting targets can be set up easily. In an open field, two poles are erected with a piece of cloth or felt hung between them. Some people make a straw dummy as a target. In the old days, past, arrows and targets were made with great care. Ancient style ringing arrows used animal bones as arrowheads. These were sharp, round shape and had four holes bored in them. When these ringing arrow were shot, air passing through the holes produced a loud ringing noise. Ancient-style targets were made of horsehide and felt. They had cloth circles made of six colors with a red bulls eye in the center. When an archer hit a circle, the circle dropped, making it easy to calculate the score.

In some place, oxen or sheep are awarded to the winners of archery competitions, with winners hanging their arrows on the heads of the ox or sheep. However, they could not claim the trophies for themselves. Instead everyone feasted together on the cooked oxen or sheep. Competitions were often organized for old, middle and young groups. The distance of shooting varied. They could be 240, 80 or 100 steps long. Often there were both standing and riding competitions. Nowadays, arrow shooting performances and competitions are held during the Spring festival, "4.18" Festival and Mid-autumn Festival. In the 1970s Qapqal Xibe Autonomous County founded a team of excellent archers. Xibe archers have participated in many national and international championships and won many gold medals. This has also enhanced the Xibe’s reputation throughout China.

Although the Xibe are renowned archers, their original Manchu traditional archery (gus khavdan) has almost been completely forgotten. There are few if any traditional bows left. When tourists go to Chapchal, the Xibe regularly put on archery performances. Recently they have built an archery display ground with a small museum, which displays more modern Western archery items than their own traditional forms. Stephen Selby of Asian Traditional Archery Research Network supplied them with 15 traditional Manchu bows made with modern materials. He ran a training class. Twelve students and their coaches took part and all of them mastered the basic skills of traditional archery with the Manchu bow. [Source: Stephen Selby, Ethnic China *]

Image Sources: Nolls China website, University of Washington; Wiki commons

Text Sources: 1) "Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Russia and Eurasia/ China", edited by Paul Friedrich and Norma Diamond (C.K. Hall & Company; 2) Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, China virtual museums, Computer Network Information Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 3) Ethnic China *\; 4) Chinatravel.com \=/; 5) China.org, the Chinese government news site china.org | New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated October 2022