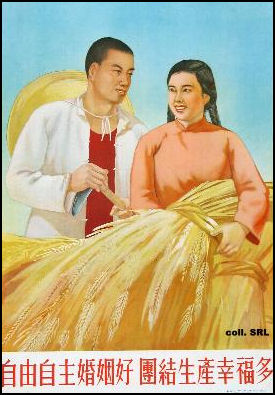

ARRANGED MARRIAGES IN CHINA

Traditionally, marriages in China have been arranged between two families and often still are. In the old days, young men and women that liked one another were not allowed to meet freely together. Young people who put their wishes for a mate above the wishes of their parents were considered immoral.

Traditionally, families had more say in regard to a marriage than the man and woman who were getting married. The man’s parents search for a prospective bride of the same social and financial status. It was not unusual for parents to arrange, and promise, their children in marriage when they were very young, or even before they were born. George P. Monger wrote in “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ The traditional Chinese practice was for the parents to undertake the bride-seeking process with girls from rich families sought by rich families and the poor also marrying among themselves. The Chinese have a saying, “Bamboo door is to bamboo door as wooden door is to wooden door.” Again, practices are changing to allow free, or freer, choice, although matchmakers or other go-betweens are still employed. The matchmaker often simply acts as an intermediary who explains the virtues of a young man or woman to the parents seeking a spouse for their child and makes the dowry and other financial arrangements between the two families.[Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ by George P. Monger, 2004 ^]

Marriages have traditionally been regarded as unions between families with matches being made by elders who met to discuss the character of potential mates and decide whether or not a they should get married. Marriages that are arranged to varying degrees are still common and traditional considerations still plays a part in deciding who marries whom. One matchmaker told the Los Angeles Times, “Marriage is for the parents, the society and future generations. It’s not about happiness or love.”

See Separate Articles: LOVE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; MARRIAGE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; GHOST MARRIAGES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; MODERN MARRIAGE TRENDS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; DATING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; LOVE HUNTERS AND HIGH-END DATING SERVICES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; WEDDINGS IN CHINA: MONEY, RULES AND LACK OF A CEREMONY factsanddetails.com ; TRADITIONAL CHINESE WEDDINGS factsanddetails.com ; WEDDINGS CUSTOMS IN CHINA: PHOTOS, THE BANQUET AND GIFTS factsanddetails.com ; CONCUBINES AND MISTRESSES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; DIVORCE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; DIVORCE LAWS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; BRIDE SHORTAGE AND UNMARRIED MEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; FOREIGN BRIDES IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Marriage: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Chinatown ConnectionChinatown Connection ; Travel China Guide travelchinaguide.com ; Agate Travel warriortours.com : Dating Chinatown Connection Chinatown Connection

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Chinese Marriages in Transition: From Patriarchy to New Familism (Politics of Marriage and Gender (2023) by Xiaoling Shu and Jingjing Chen Amazon.com; “Marriage and Inequality in Chinese Society” by Rubie S. Watson and Patricia Buckley Ebrey Amazon.com; “Arranged Companions: Marriage and Intimacy in Qing China” by Weijing Lu Amazon.com “Arranged Marriage: The Politics of Tradition, Resistance, and Change (Politics of Marriage and Gender: Global Issues in Local Contexts) by Péter Berta, Asha L. Abeyasekera, Amazon.com; “My Chinese Marriage” by Mae M. Franking and Katherine Anne Porter Amazon.com; “Marriage” (Chinese Folklore Culture Series) by Hunjia Juan Amazon.com; “Marriage and Family in Modern China (The Library of Couple and Family Psychoanalysis) by David E. Scharff Amazon.com; “The Ugly Wife Is a Treasure at Home: True Stories of Love and Marriage in Communist China” by Melissa Margaret Schneider Amazon.com; “Handbook on the Family and Marriage in China (Handbooks of Research on Contemporary China series) by Xiaowei Zang, Lucy X. Zhao Amazon.com

Arranged Marriage Very Much Alive in Modern China

Karoline Kan wrote in New York Times’s Sinosphere: “Although arranged marriages were discouraged after the fall of the last imperial dynasty in 1911 and banned by the Republican government in the 1930s, Chinese millennials, often portrayed as the excessively indulged and protected products of the one-child family policy, now find themselves yielding to parents who are ready to provide them with everything, even a spouse. [Source: Karoline Kan, Sinosphere, New York Times, February 16, 2017]

“Zhang Yashu, a 25-year-old woman from Shenyang, the capital of the northeastern province of Liaoning, said none of her previous boyfriends had satisfied her mother.“My mom means well. She wants me to find a good husband — by her standards,” Ms. Zhang said in an interview. “I don’t feel a rush to get married, but my parents are worried I won’t be able to find a good husband, especially as their friends’ children are all settling down.”

“Ms. Zhou said one reason Chinese parents had so much say over their child’s marriage was that many of the parents were paying for it. According to a 2015 report by the All-China Women’s Federation, the average age at marriage is 26. But the expenses of marriage exceed what most Chinese this age can afford. According to one industry report, in 2016 the average cost of a wedding in Shanghai was 200,000 renminbi, about $30,000. That does not include the costs of an apartment and a car, which are widely considered prerequisites for an engagement and typically bought by the young man’s parents.

Zhou Xiaopeng, a relationships counselor on the dating website Baihe, said, “Matchmaking remains popular because, from the start, each side knows exactly what the other’s background is.“It’s efficient when candidates are screened by parents.” Lu Pin, a feminist and cultural critic, said patriarchal values were never entirely eliminated from Chinese culture, and there were signs that they were making a comeback. “Many Chinese families have entered the middle class now, and they want to solidify their status by marrying people from a similar background,” Ms. Lu said. “It’s a decision that affects the whole family.”

“Without parents’ help, she said, many young Chinese cannot afford to marry, and even afterward they still need help from their parents on issues like child care. “Too much protection and support from parents has given rise to a generation that has never really grown up,” Ms. Zhou said. “Many clients tell me their marriage was based not on love, but on ‘convenience,’ that their parents told them it would be a good match,” she said. “When asked what they expect of their future partner, many say they trust their parents’ experience. That’s not the attitude of an adult.” Some commenters on Weibo agreed. “China is a country full of grown-up babies,” one user wrote.

Matchmakers in China

China’s matchmaking tradition stretches back more than 2,000 years, to the first imperial marriage broker in the late Zhou dynasty. The goal of matchmakers ever since has usually been to pair families of equal stature for the greater social good. Up until a century ago marriage registry forms required the seal of an “introducer.” In the old days, arranged marriages among the upper classes were intended to firm up a family's social position and status and extend the family's social network. Rich men could have as many wives as they could afford. Many marriages were worked out when the bride and groom were still children. Occasionally this occurred before they were born if two families were intent on forming a union.

A traditional Chinese marriage was often set up by a matchmaker hired by the parents when potential bride and groom reached marriageable age. In their search, the matchmakers took various things into consideration: education, family background, and a kind of fortunetelling based on year, date and time of birth. One saying that dates back to the 7th century B.C. goes: “How do you split firewood? Without an ax it can’t be done. How do you go about finding a wife? Without a go-between it can’t be done.”

In a marriage arranged by a matchmaker, the matchmaker hosts a tea where the young couple meet for the first time. The young woman serves tea to the young man and his relatives. If the man likes the woman he can propose marriage by offering her an embroidered red bag on the saucer in which the cup or tea was served. If the woman accepts the saucer she accepts the proposal and the couple is engaged.

There are more than 20,000 matchmaking agencies in China. They have names like the Tianjin Municipal Trade Union Matchmaker’s Association and the Beijing Military and Civilian Matchmaking Service. Some of them are unscrupulous brokers who try to con women into marrying lonely rural men.

Modern Go Between Process

George P. Monger wrote in “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons”: “ The modern Chinese wedding has changed in details over the years, although the form of the wedding has remained the same. As noted above, the Chinese population today contains more men than marriageable women. The women, therefore, have a greater choice of marriage partner, and there is more possibility for the couple to make their own choices rather than having the partner chosen by their parents and a go-between.A wedding in Hong Kong today might follow Chinese traditions, with adaptations to take account of the circumstances of the city and the contemporary world and influence from the Western world. For example, there may be a bridal shower before the wedding and the groom may have a bachelor party. [Source: “Marriage Customs of the World From Henna to Honeymoons” by George P. Monger, 2004 ^]

The checking of compatibility between the bride and groom will only be carried out if the families are particularly superstitious; if the fortune-teller suggests that the two are compatible, the families will exchange family trees. However, the Chinese calendar will still be consulted to find a propitious day for sending the wedding gifts by the groom’s family to the bride’s.

Today, often the gifts are some gift-wrapped food — dried seafood and fruit baskets — and this represents both the initial gifts and the formal gifts that were once sent on separate occasions. Instead of a monetary gift the groom will pay all or a portion of the cost of the wedding, but this can lead to problems and delay in the marriage if the two families cannot agree on the number of guests and tables each can have at the banquet.

Because of problems of housing in China today, it is not always possible for the couple to have a new bed and a new home. Today, the bed linen is changed to traditional red as a symbol of the making of the new bridal bed. The tradition of the bridal gift to the groom is usually not followed by modern couples, but the bride may help in paying for the banquet, and this is sometimes seen as being the bride’s gift to the groom.

Matchmaking and Dating in Modern China

Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore wrote in The Telegraph, “ China’s spectacular economic growth has, for many, turned dating and marriage into a commercial transaction, and material expectations from marriage have soared. It is often said – only half-jokingly – that to compete even at the lower reaches of the urban Chinese dating market men must have at least a car and a flat. The matchmaking industry has gone into overdrive, not just to cater to the rich but also because of government unease over the numbers of older single professional women.[Source: Clarissa Sebag-Montefiore, The Telegraph, October 22, 2013 ^|^]

“Although forced or arranged marriage was banned in 1950, finding a partner remains a formal process for many.“Marriage is seen as a factor in promoting social stability,” explains Leta Hong Fincher, the author of a forthcoming book on “leftover women” and gender inequality in China. “There is lots written in the state media about how all these tens of millions of unmarried men pose a threat to society. But at the other end of the spectrum, unmarried women who are not fulfilling their 'duty to the nation’ by getting married and having children are also seen as a threat.” As it has moved from communism towards a freer economy China has become a richer – and also increasingly unequal – society. And as a disproportionate few make fortunes, leaving tens of millions of ordinary people behind, many women see marrying a rich man as a short-cut to wealth. ^|^

Brook Larmer wrote in the New York Times, “Three decades of combustive economic growth have reshaped the landscape of marriage in China. China’s transition to a market economy has swept away many restrictions in people’s lives. But of all the new freedoms the Chinese enjoy today — making money, owning a house, choosing a career — there is one that has become an unexpected burden: seeking a spouse. This may be a time of sexual and romantic liberation in China, but the solemn task of finding a husband or wife is proving to be a vexing proposition for rich and poor alike. “The old family and social networks that people used to rely on for finding a husband or wife have fallen apart,” said James Farrer, an American sociologist whose book, “Opening Up,” looks at sex, dating and marriage in contemporary China. “There’s a huge sense of dislocation in China, and young people don’t know where to turn.” [Source: Brook Larmer, New York Times, March 19, 2013 ^-^]

“The confusion surrounding marriage in China reflects a country in frenzied transition. Sharp inequalities of wealth have created new fault lines in society, while the largest rural-to-urban migration in history has blurred many of the old ones. As many as 300 million rural Chinese have moved to cities in the last three decades. Uprooted and without nearby relatives to help arrange meetings with potential partners, these migrants are often lost in the swell of the big city. Demographic changes, too, are creating complications. Not only are many more Chinese women postponing marriage to pursue careers, but China’s gender gap — 118 boys are born for every 100 girls — has become one of the world’s widest, fueled in large part by the government’s restrictive one-child policy. By the end of this decade, Chinese researchers estimate, the country will have a surplus of 24 million unmarried men.^-^

“Without traditional family or social networks, many men and women have taken their searches online, where thousands of dating and marriage Web sites have sprung up in an industry that analysts predict will soon surpass $300 million annually. These sites cater mainly to China’s millions of white-collar workers. But intense competition, along with mistrust of potential mates’ online claims, has spurred a growing number of singles — rich and poor — to turn to more hands-on matchmaking services. Today, matchmaking has warped into a commercial free-for-all in which marriage is often viewed as an opportunity to leap up the social ladder or to proclaim one’s arrival at the top. Single men have a hard time making the list if they don’t own a house or an apartment, which in cities like Beijing are extremely expensive. And despite the gender imbalance, Chinese women face intense pressure to be married before the age of 28, lest they be rejected and stigmatized as “leftover women.” ^-^

Matchmaking Dynamics in China

In 2019, Sijia Li and Helen Roxburgh of AFP wrote: “Pursuing romance had not been available to many Chinese women in the past. Sandy To, a sociologist at the University of Hong Kong, said marriage had traditionally been a "must" in patriarchal Chinese society. But Tan says that the one-child policy — which came into force in 1979 and limited the size of most families — has created "a generation of self-confident and resourceful women." A preference for boys meant a generation of sex-selective abortions and abandoned baby girls, and in 2018, China still had the world's most skewed gender ratio at 114 boys born for every 100 girls. [Source: Sijia Li and Helen Roxburgh, AFP, December 6, 2019]

“For many women, the policy changed their family dynamics. Parents of the female children "raised them as sons", says Roseann Lake, author of a book on China's unmarried women. "All of those things that traditionally you needed to find in a man — a house, financial security — they were raised with it," she says. As their economic situation improves, fewer women are choosing to get married.“China's marriage rate — the number of marriages per year — has been in decline over the last five years. Last year it reached 7.2 per 1,000 people, according to the National Bureau of Statistics. Once their basic needs are guaranteed, more women are looking to satisfy their need for "emotional and self-fulfilment," says Lake.

Brook Larmer wrote in the New York Times, “One Friday last fall, I met with Yu Jia and her son Zhao Yong at a McDonald’s in western Beijing. Now 39, Mr. Zhao has a youthful, unlined face. Still, he worries that time is passing him by. To save money and to enhance his marriage prospects, he works two jobs simultaneously — one selling microwaves, the other cosmetics — crisscrossing the city on his electric bike. He earns about $1,000 a month, and sometimes adds $80 more by working weekends as a film extra. [Source: Brook Larmer, New York Times, March 19, 2013 ^-^]

“It is a respectable income, but hardly enough to attract a bride in Beijing. Even in the countryside, where men’s families pay bride prices, inflation is rampant. Ms. Yu’s family paid about $3,500 when Mr. Zhao’s older brother married 10 years ago in rural Heilongjiang. Today, she said, brides’ families ask for $30,000, even $50,000. An apartment, the urban equivalent of the bride price, is even further out of reach. At Mr. Zhao’s current income, it would take a decade or two before he could afford a small Beijing apartment, which he said would start at about $100,000. “I’ll be an old man by then,” he said with a rueful smile.^-^

“Mr. Zhao has met several women on online dating sites, but he lost faith in the Internet when several women lied to him about their marital status and family backgrounds. His mother, however, had come through, arranging a meeting between him and the daughter of the woman she had met in the marriage market. Not long after our conversation in McDonald’s, Mr. Zhao met the woman at a coffee shop. It was, he told me later, even more awkward than most first dates. A rural migrant and door-to-door salesman, he struggled to find a shared topic of interest with the woman, a 35-year-old entrepreneur and Beijing native who had arrived driving a BMW sedan. ^-^

“The lack of chemistry didn’t seem to bother the woman, who told him about her profitable photo business and the three Beijing apartments she owned. Mr. Zhao didn’t find her unattractive, but how was he supposed to respond? Then, even before broaching the possibility of a second date, he said, the woman made a proposition: if they married, he wouldn’t have to work again. “She said she made enough money for the two of us,” he said. “I could have anything I want.” The marriage proposal stunned him. He had never heard a woman talk in such blunt, pragmatic terms. A life of wealth and leisure sounded tempting. Still, in the end, he couldn’t imagine being subordinate to a woman. “If I accepted that situation,” he asked me, “what kind of man would I be?” ^-^

“It took Mr. Zhao several days before he worked up the nerve to tell his mother he had rejected the offer. He knew how hard she had worked, how much she had been counting on this. The news frustrated Ms. Yu. “Kids these days are way too picky,” she said. Even with this setback, Ms. Yu has continued her daily pilgrimage to the marriage markets. When I last spoke to her early this month, she was arranging dates for her son with three new marriage candidates she had found. “I’m optimistic,” she said. After all these years, hope is what keeps her going.” ^-^

Parent Meddling and Unhappy Marriages in China

Laurie Burkitt of the Wall Street Journal wrote: “Many marriages are certainly based on personal choice, without the help of mom and pop, but sociologists say it’s likely that parental guidance is far more common in China than in the U.S. Anecdotally, children across China feel the pressure of rising healthcare costs and the lack of investment vehicles, so some end up acquiescing to economics-driven marriages. That said, even in the U.S., some have recently queried whether parents should be more involved in directing what goes on at the altar. [Source: Laurie Burkitt, China Real Time, Wall Street Journal, February 11, 2015 +++]

According to a World Bank research paper titled “Love, Money, and Old Age Support: Does Parental Matchmaking Matter?” Chinese marriages in which parents play matchmaker and pick spouses for their children are likely to be unhappy. “Parental matchmaking is robustly correlated with lower marital harmony,” the report said. +++

Burkitt wrote: “The reason for the unmerry marriages is that parents put their own needs for elderly care ahead of love, say researchers. Lacking hearty social security, Mom and Dad worry about the post-retirement years and how they’ll be cared for, so they look for wealthy mates for their children who will provide financial security. They also seek submissive mates who will happily tend to chores, boosting household productivity, the report said. +++

“Researchers surveyed 3,400 rural couples and 3,800 urban couples in seven provinces across China in 1991. While the data might be old, said Colin Xu, one of the authors, parental influence remains important in Chinese culture. Traditionally arranged marriages in which children have no say in their marital fate are no longer as prevalent in current-day China, but Mr. Xu said Chinese parents still tend to be heavy-handed in the match-making process. In parks all across China, mothers and fathers meet for a marital NFL draft, swapping statistics regarding their children’s education, assets, salary and profession. +++

“While the World Bank’s research doesn’t find many positive effects for couples whose parents play matchmaker, the paper doesn’t point to parental matchmaking as a cause for China’s climbing divorce rates. Still, regardless of a marriage’s level of happiness, many Chinese parents do succeed in their economic goals in more ways than one. The research said parent-patched marriages yield in higher income for couples in urban areas.

Parents Making Matches in Parks

Marriage is still viewed as a necessary step in every adult's life and parents are often very much engaged in finding mates for their children. Chinese parents flood public parks, armed with resumes of their unmarried adult children, to meet other parents with children to marry off, hoping to attract good matches. Some meet other parents in parks such as Zhongshan Park in Beijing and exchange notes on height. wealth, education, food preference, Chinese animal sign and even birthmarks and blood type in their search for a good match. "As soon as I hit 22, my mother visited Zhongshan Park every day," Beijing native Xu Qiang, 25, told the Strait Times. "She told me if I delay getting married, I won't be able to find a good wife later."

Parents representing daughters often outnumber parents representing sons by a margin of 10 to 1, mainly because of the biological clock and those with older sons don’t waste their time, and 90 percent of the children the parents are seeking mates for are in their 30s. Parents with tall sons with good jobs or a degree from a prestigious university are often mobbed. The Los Angeles Times reported one 80-year-old woman at the park looking for wife for her 51-year-old son.

Chinese children have different view about their parents search for mates for them in parks. A 27-year-old artist told the Los Angeles Times, “I’m not happy about this. I told my mother not to go to the park. I don’t need her help.” A 23-year-old nurse said, “I have a pretty small circle of friends and no one in sight as a boyfriend. If my parents found someone I’d probably take a look at them.”

Brook Larmer wrote in the New York Times, “In a Beijing park near the Temple of Heaven, a woman named Yu Jia jostled for space under a grove of elms. A widowed 67-year-old pensioner, she was clearing a spot on the ground for a sign she had scrawled for her son. “Seeking Marriage,” read the wrinkled sheet of paper, which Ms. Yu held in place with a few fragments of brick and stone. “Male. Single. Born 1972. Height 172 cm. High school education. Job in Beijing.” Ms. Yu is....a parent seeking a spouse for an adult child in the so-called marriage markets that have popped up in parks across the city. Long rows of graying men and women sat in front of signs listing their children’s qualifications. Hundreds of others trudged by, stopping occasionally to make an inquiry. Ms. Yu’s crude sign had no flourishes: no photograph, no blood type, no zodiac sign, no line about income or assets. The sign didn’t even specify what sort of wife her son wanted. “We don’t have much choice,” she explained. “At this point, we can’t rule anybody out.” [Source: Brook Larmer, New York Times, March 19, 2013 ^-^]

“In the four years she has been seeking a wife for her son, Zhao Yong, there have been only a handful of prospects. Even so, when a woman in a green plastic visor paused to scan her sign that day, Ms. Yu put on a bright smile and told of her son’s fine character and good looks. The woman asked: “Does he own an apartment in Beijing?” Ms. Yu’s smile wilted, and the woman moved on. One afternoon last summer, however, there was a glimmer of hope. Ms. Yu traded information with a mother who didn’t dismiss her son out of hand. The woman’s daughter was 35, with a good education, a substantial income and a Beijing residency permit. She was, in some eyes, a leftover woman. Ms. Yu e-mailed Mr. Zhao’s picture to her that evening. The daughter declined to meet at first. A week later, she called back: “Yes, maybe.” Ms. Yu was thrilled. It was her first solid lead in months. ^-^

One Chinese Mother's Quest for a Wife for Her Son

Brook Larmer wrote in the New York Times, “Yu Jia kept her search a secret at first. She didn’t want to risk upsetting her son so soon after a trying time for the family. Ms. Yu and her husband, who was sick with lung cancer, had left the northern city of Harbin in the hope of finding better treatment for his cancer in Beijing, where two of their sons already lived. The husband hung on for a year before he died in 2009 — not long, but long enough to wipe out the last of the family’s $25,000 in savings. Devastated, Ms. Yu stayed in an apartment on the outskirts of Beijing with her sons — one married; the other, Zhao Yong, still single at 36. But one day, Ms. Yu came upon a crowd swarming under the elm trees near the Temple of Heaven. [Source: Brook Larmer, New York Times, March 19, 2013 ^-^] “Her life suddenly had a new purpose. “I decided that I will not go home until I find a wife for my son,” she told me. “It’s the only thing left unfinished in my life.” Plunging into a crowd of strangers with her sign made Ms. Yu feel awkward at first. Her elder two sons had found wives in traditional ways, one through a matchmaker, the other through a friend. But Mr. Zhao, her youngest, had not. After losing his job in an electronics factory in Harbin, he followed his hometown sweetheart to Beijing. They were in love and planned to marry. But her family demanded a bride price — a sort of dowry used in rural China — of $15,000. His family could not afford it, and the relationship ended. ^-^

“”Mr. Zhao threw himself into his work as a driver and salesman. His former girlfriend married and had a baby. He told his mother he had little time to think about marriage. The strangers in the park, uprooted from their traditional family and hometown networks, shared similar stories, and Ms. Yu found comfort there. Many other parents, she realized, were even more frantic; they had only one child because of China’s policy. (Ms. Yu, as a rural mother, was permitted to have multiple offspring.) The marriage candidates on offer in the parks, she discovered, were often a mismatch of shengnu (“leftover women”) and shengnan (“leftover men”), two groups from opposite ends of the social scale. Shengnan, like her son, are mostly poor rural men left behind as female counterparts marry up in age and social status. The phenomenon is exacerbated by China’s warped demographics, as the bubble of excess men starts to reach marrying age. ^-^

“Ms. Yu’s son, Mr. Zhao, was angry when he found out that she had been searching for a wife for him. He didn’t want to rely on anybody else’s marketing, especially his mother’s. But he has since relented. “I see how hard she works, so I can’t refuse,” he told me. Ms. Yu doesn’t tell her son about the parents who scoff when they find out he has no property and no Beijing residency permit. But the handful of young women she’s persuaded to meet him never made it to a second date. ^-^

Looking for a Husband for a Chinese Leftover Woman

Didi Kirsten Tatlow wrote in the New York Times, “China has about 20 million more men under 30 years of age than women, according to official news reports — largely the result of gender selective abortion, with many parents preferring a son to a daughter. So why is the phenomenon of “leftover women” apparently so widespread? Aren’t desperate men snapping up available women? Not exactly. Traditional attitudes demand that a man earn more than a woman, meaning that as women earn increasingly more they are pricing themselves out of the marriage market.” [Source: Didi Kirsten Tatlow, New York Times, April 23, 2013]

Brook Larmer wrote in the New York Times, “Finding a Chinese spouse can be even more challenging for so-called leftover women, even if they often have precisely what the shengnan lack: money, education and social and professional standing. One day in the Temple of Heaven park, I met a 70-year-old pensioner from Anhui Province who was seeking a husband for his eldest daughter, a 36-year-old economics professor in Beijing. [Source: Brook Larmer, New York Times, March 19, 2013 ^-^]

“My daughter is an outstanding girl,” he said, pulling from his satchel an academic book she had published. “She’s been introduced to about 15 men over the past two years, but they all rejected her because her degree is too high.”The failure compelled him to forbid his youngest daughter from going to graduate school. “No man will want you,” he told her. That daughter is now married in Anhui, with an infant son whom the pensioner, so busy seeking a spouse for her older sister in Beijing, rarely sees. ^-^

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Chinese government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated September 2021