FESTIVAL TRADITIONS IN CHINA

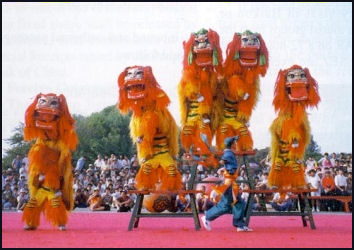

Lion dance

Festivals, holidays, and other activities have traditionally been set at times during the lunar calendar. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “As early as the Shang dynasty (16th-11th c. BC), a calendrical system had already been established. According to the seasons, a year was divided into about 360 days composed of 24 "half-month" and 72 "five-day week" periods. This set the foundation for calculating when to observe or celebrate certain events during the year. Later, other activities related to traditional agrarian society, everyday life, and religious observances were also integrated into the calendar to create a variety of folk ceremonies, such as for offering blessings, averting disaster, dispelling evil, and driving out pestilence. Over the generations, they gradually formed a rich tapestry of activities, festivals, and holidays, some of which are still observed today.[Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei]

“Each folk observance associated with a particular festival or tradition has a long history, and some can even be traced back to the origins of Chinese civilization with the worship of the heavens and earth. Many also incorporated elements of superstition, such as the legend of the "year" being a ferocious beast that had to be driven away with rituals and firecrackers in order to usher in the New Year. As a way of revering the heavens and earth as well as showing gratitude for a bountiful harvest, the custom of paying homage to the heavens, earth, and the moon also formed. In the Shang and Chou dynasties (16th-3rd c. BC), for example, shamans would go to the riverbank to conduct a ceremony of ritual cleansing on the first cyclical "ssu" day of the third lunar month. In the Han dynasty (206 BC-AD 220), Emperor Wu-ti was a pious follower of the Almighty One (T'ai-i) spirit, so offerings were made to the Almighty One before military expeditions and on holidays. The grandest offering was made on the 15th day of the first lunar month, the first full moon of the new year. Starting from dusk and throughout the night, offerings were made in the form of huge lanterns, a custom that was eventually adopted by ordinary people and which eventually became the Lantern Festival that is celebrated today. In the T'ang dynasty (618-907), society prospered as a whole and many of the superstitions, primitive beliefs, and legends of the past regarding annual events gave way to activities of pure joy and celebration. For example, firecrackers not only served a practical function for driving away the old year, but they also became a symbol of joy for the new year. In addition, the Lantern Festival became a time for all to appreciate colorful lanterns; the ceremony of ritual cleansing at a river became the occasion for a literary party; and the full moon became a time to gather together, especially at the Mid-Autumn Festival.

“Each custom and activity related to an annual event is unique, and the celebrations surrounding them caught the attention of many painters over the years to become known as "holiday pictures." They include illustrations of lantern festivities, the ceremony of ritual cleansing, dragon boat races, the test of skill at weaving, admiring the mid-autumn moon, and going up to the hills. Of particular note is Huang Yueh's (1750-1841) "Peace and Prosperity at the New Year," in which he recorded many of the customs surrounding New Year's celebrations in traditional China, such as New Year couplets, offerings, and firecrackers. He described with great detail the joyous celebrations of common folk at this time of the year. Wu Pin (fl. 1591-1643) in "Record of Annual Events and Activities" chose to record activities and events related to the months. Wen Cheng-ming (1470-1559) in "Spring Ablution at the Orchid Pavilion" painted a fanciful rendering of drinking wine from cups floating on a stream enjoyed by Wang Hsi-chih and his friends at the Orchid Pavilion. The semi-legendary Chung K'uei, the Demon Queller, was said to have been ugly and frightening in appearance. Therefore, on the Dragon Boat Festival, his portrait was hung in the belief that it would drive away evil and pestilence. However, in Hua Yen's (1682-1756) "Chung K'uei on the Dragon Boat Festival", he is shown sitting leisurely appreciating the garden scenery as mischievous goblins add a humorous touch to this figure. In Leng Mei's (fl. 18th c.) "Appreciating the Moon," the artist took a different approach to festive moon-viewing gatherings by showing a scholar sitting quietly as he appreciates the moon.

Good Websites and Sources: Chinese Calendar PaulNoll.com PaulNoll.com ; Wikipedia article on traditional holidays Wikipedia ; Wikipedia article on Chinese Calendar Wikipedia ; Chinese Astrology Chinatown Connection on Astrology Chinatown Connection ; Chinatown Connection on the Chinese Zodiac Chinatown Connection ; Wikipedia article on Chinese Astrology Wikipedia

Articles on Holidays and Festivals in this Website: CHINESE LUNAR CALENDAR AND CHINESE ACCOUNTING OF TIME factsanddetails.com; CHINESE HOLIDAYS factsanddetails.com ; QINGMING (TOMB-SWEEPING DAY): HISTORY, PRACTICES AND BANS factsanddetails.com ; HUNGRY GHOST MONTH factsanddetails.com ; MID-AUTUMN FESTIVAL AND MOONCAKES factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE NEW YEAR: FAMILIES, FIREWORKS AND PHONES factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE NEW YEAR CUSTOMS, OBLIGATIONS, RITUALS AND FOOD factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE NEW YEAR FIXTURES: LONG TRIPS HOME, MIGRANT WORKERS AND PAYING DEBTS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE NEW YEAR GALA TV SPECIAL factsanddetails.com ; factsanddetails.com ; LOSAR (TIBETAN NEW YEAR) factsanddetails.com ; TIBETAN RELIGIOUS FESTIVALS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Good Luck Life: The Essential Guide to Chinese American Celebrations and Culture”by Rosemary Gong and Martin Yan Amazon.com; “Chinese Festivals” by Wei Liming Amazon.com; “Mooncakes and Hungry Ghosts: Festivals of China” by Carol Stepanchuk and Charles Choy Wong Amazon.com; “Moonbeams, Dumplings & Dragon Boats: A Treasury of Chinese Holiday Tales, Activities & Recipes” by Nina Simonds , The Children's Museum Boston, et al. Amazon.com; “The Demon King and Other Festival Folktales of China” by Carolyn Han, Ji Li (Illustrator), Jay Han Amazon.com; “Festivals of China's Ethnic Minorities” by Xing Li Amazon.com

Chinese Festival Paintings

Hokchew Lantern Festival

China has a long tradition of festival paintings. Describing a series of album leaf paintings called “Record of Annual Events and Activities by Wu Pin (fl. 1591-1643, Ming Dynasty, the National Palace Museum, Taipei says: “ “Wu Pin, a native of Fukien province, was known for his unusual paintings of Buddhist figures. From the middle of his career, however, he also often painted landscapes featuring exaggerated and very precipitous mountains. This masterpiece of Wu's painting includes less fantastic but equally fascinating scenery, and it records a selection of activities associated with the lunar months. The painting is ink and colors on paper on a 29.4-x-69.8-centimeter album leaves. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei]

“The first leaf features the Lantern Festival, which takes place at the full moon on the fifteenth day of the first lunar month two weeks after the start of the new year. Many people have turned out here to appreciate the lanterns, especially the huge ornamental "lantern mountain." The second leaf represents the activities of sericulture (the cultivation and processing of silk) in preparation for the silk market in the second lunar month. Here, everybody pitches in to gather mulberry leaves in the background, raise silkworms for the cocoons, and then process and weave the thread. The third leaf shows ladies taking turns on a swing, an activity that originated in the north as a form of exercise and that eventually became a pastime in China. By the T'ang dynasty (618-907), it was popular around the time of the Tomb Sweeping Festival, the last day of the third lunar month. The fourth leaf is entitled "bathing the Buddha" and represents the eighth day of the fourth lunar month, which is celebrated as the birthday of the Buddha. It is said that when the Buddha was born, nine dragons spouted water to bath the infant, hence the name of this holiday. In this temple setting, monks are gathering in processions to pay homage to the sculpture of the newly born Buddha in the central hall.

The sixth leaf represents the winding down of summer, which refers to the sixth lunar month when the end of summer approaches and the heat begins to dissipate. Cooling off is one of the most important activities at this time of the year. Here, figures enjoy a cool waterside pavilion. The seventh leaf is for the Ghost Festival, which takes place on the fifteenth day of the seventh lunar month. Taoists observe this day by reciting prayers and making offerings to appease the spirits, and Buddhists make offerings to the Buddha and recite scriptures by candlelight to relieve the suffering of the spirits. Here, a Buddhist temple is shown at the left.

The eighth leaf involves gatherings to view the moon, which is associated with the Mid-autumn Moon Festival on the fifteenth day of the eighth lunar month. In this work, the moon is reflected in the water in front of the scholars seated on a rock in the middle. In the courtyard to the left is an offering to the moon as other scholars are shown in a boat in the lower part and on a bridge viewing the waterfall. The ninth leaf portrays a scene of going to the hills for appreciating the scenery. In the tenth leaf is a scene of reviewing troops, which took place in antiquity during the tenth lunar month. The emperor at that time would reward officials and hold military exercises. Here, land and naval demonstrations take place in front of the official seated to the right and the one on the large ship. The eleventh leaf shows the appreciation of snow, which here has covered the scenery. In the past, an abundant snow meant sufficient water for crops in spring. Eventually, the appreciation of snow also became a winter pastime for scholars who sought inspiration in and reflection on the purity of nature. In the twelfth leaf and last one in this album is a scene in which the actors portraying harmful spirits and diseases are being driven out of town in a ritual dance. It was mostly held at the time of the Chinese New Year in grand fashion. Here, the procession takes place on a bridge as figures in front beat a large drum with actors behind.

Chinese Lantern Festival

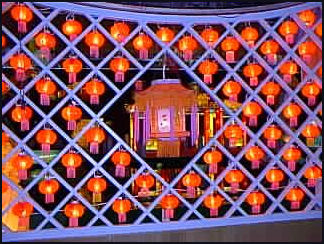

The Lantern Festival takes place on the 15th day or 1st full moon of the 1st lunar month, two weeks after Chinese New Year, in late February or early March. Marking the end of the Chinese New Year period and not a public holiday, it is celebrated with lantern riddles, round sweet dumplings, dragon dances, lion dances, folk boat dances and trotting donkey dances. The first full moon of the New Year, which is visible on this day, is regarded as the first day of spring. Dumplings symbolize family reunions and are a pun in Chinese because the character for "round" and "reunion" are the same. In the old days this holiday was celebrated with contemplation of the moon, the burning of stubble in the fields, and the consumption of a special liquors.

The Lantern Festival takes place on the 15th day or 1st full moon of the 1st lunar month, two weeks after Chinese New Year, in late February or early March. Marking the end of the Chinese New Year period and not a public holiday, it is celebrated with lantern riddles, round sweet dumplings, dragon dances, lion dances, folk boat dances and trotting donkey dances. The first full moon of the New Year, which is visible on this day, is regarded as the first day of spring. Dumplings symbolize family reunions and are a pun in Chinese because the character for "round" and "reunion" are the same. In the old days this holiday was celebrated with contemplation of the moon, the burning of stubble in the fields, and the consumption of a special liquors.

Dating back to the Han Dynasty, the 2,000-year old event is a time for family reunions and visits to crowded lantern-lighting shows and some riddle-solving. Villages and cities all over China fill with bright lights to mark the end of Chinese New Year celebrations. Lantern riddles are written on colorful lanterns. Rewards are offered to those who can solve them. In the old days the lanterns were sometimes quite spectacular. Describing the festival at Hangzhou’s West Lake, the great 16th century historian Zhang Dai wrote that one could “enter the center of a lantern...into the fire, metamorphosed, not knowing if these were fireworks being set off in the prince’s palace. Or if this were a prince’s palace composed of fireworks.”

At night of families traditionally walked in the street, carrying lanterns, often shaped like the zodiac animal of that lunar year. Some communities and neighborhoods still organize walks, and the sight with children parading with their animal lanterns. It is also a time when families feast on glutinous rice dumplings (yuanxiao) that are round — the symbol of family unity and togetherness. The annual lantern show at Yuyuan Garden in Shanghai — declared an intangible cultural heritage of Shanghai — features a plethora of lanterns of all shapes and sizes and arrangements, with an emphasis on traditional round red lanterns with golden tassels

On the holiday in 2021, the BBC reported: In Beijing, many visitors took selfies at a colourful lantern show. A rainy day did not stop people from admiring beautiful lanterns in Wenzhou, eastern Zhejiang province. Performers in Wuhan, central Hubei province, wore face masks as they prepare for the traditional dragon dance. Cities, such as Binzhou in northern Shandong province were transformed by lanterns and fireworks. A giant Ferries wheel was illuminated there. Crowds gathered to see the lighting of giants LED lanterns in Chengdu, Sichuan province. A woman danced inside a huge red lantern in Shenyang, north-eastern Liaoning province. Train attendants dressed in historical costumes and holding musical instruments on board a train in Zhengzhou. Bearers brought out the traditional Chinese red sedan chairs in the central city of Enshi. [Source: BBC, February 27, 2021]

Chinese Lantern Festival Dances

Dragon dances feature huge dragons made of colored paper, cloth, and small battery-lit lanterns shaped like fishes and shrimp strung together with pieces of cloth. To the deafening sounds of gongs and drums the "dragon" dances up and down the streets while strings of firecrackers and fireworks are set off. There are special moves. It is important for dances to be well coordinated. There are professional dragon dancers and dragon dancing competitions.

In the lion dance, two dancers wear a lion costume which works a bit like the horse costumes used in old vaudeville routines. One dancer is the head and forelegs. The other dancer is the tail and hind legs. Together as the "lion" they performs feats like the "playing with water trick" and the "climbing the shed trick."

Boat dancers are women or men disguised as women who wear a boat-shaped props around their waist that have pieces of silk that hand down and cover their legs. While singing the dancers imitate boat movements while a boat man follows them. The trotting donkey dance is similar to the boat dance but the story and props are different. The women in this dance wear donkey props around their waists and pretend they are carrying child in their arms. A man follows behind the "donkey" with a whip. The "donkey" sometimes goes fast, sometimes slow and sometimes falls in a pit while the man works up a big sweat wrestling and struggling with the animal.

Chinese Lantern Festival History

There are many legends about the origin of the Lantern Festival. The custom dates back to the Western Han Dynasty (206 B.C. to A.D. 220) (206 B.C.- A.D. 24) when Buddhism flourished. According to one legend, an emperor learned that Buddhist monks marked the 15th day of the first lunar month by paying homage to sarira (cremated remains of Buddha) and lighting lanterns. So the emperor ordered that lanterns be lit in the imperial palace and in temples on that day. It developed into a grand festival among all people. Other legends involve prayers to the Taiyi, the god of heaven, who was said to bring light to the world. [Source: China.org]

One old custom for Lantern Festival is guessing lantern riddles. In old days people would write riddles on a piece of paper and post them on lanterns. Someone who had an answer would remove the riddle paper and take it to the lantern's owner. If the answer was right, the guesser would receive a small gift. The practice began in the Song Dynasty (960-1279). Riddle guessing is harder today. One lantern designer said," "Maybe some riddles will be written on the lanterns, but there is no one on site to verify the correct answers." Another important tradition that is still observed today is eating rice balls, yuanxiao or tangyuan, meaning reunion. Made with glutinous rice, they are usually filled with something sweet, such as rose petals, sesame, red bean paste, ground walnuts or dried fruit.

In February 2004, 37 people were killed at a lantern festival in Miyung County in a northern suburb of Beijing, in a stampede which began when a man fell on a crowded bridge, setting off a chain reaction. Most of those who died suffocated to death. One witness told AP, “One person fell down...and caused many people to fall down. There was a stampede. It was a lot of people. I’m not sure how many. These things are packed.”

Lantern Festival Paintings

“Beautiful Scene for the New Year” by Ch'en Shu (1660-1736, Qing Dynasty) is a "sketch from life" of a flower setting offered on the Lantern Festival, the middle of the first lunar month marking the end of the New Year's festivities. It depicts an assemblage of chimonanthus, camellia, dahlia, and narcissus, all blossoms associated with the first lunar month and representing the coming warmth of spring in a festive spirit to greet the New Year. In painting the planter, the artist used the method of showing the ground. These plants in a Lung-ch'üan-style ceramic planter appear with an ornamental rock, arranged according to size and color to make a pleasing combination of flowers and bonsai. Next to the planter are lily roots, persimmon, spirit fungus, and an apple, the terms for which in Chinese are homonyms for the auspicious phrase, "May all things go as you wish." The painting is a Hanging scroll, ink and colors on silk, 96.8 x 47 centimeters

“Activities of Peace and Joy” is 18.5-x-24.3-centimeters Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) album, with ink and colors on silk, that consists of twelve leaves. Four deal with women and children of the court at the time of the New Year and Lantern Festival. Depicted here are lantern toys in such shapes as an elephant, crane, deer, bat, hawk, rabbit, and the God of Literature. Children are also seen playing with a kite and a shuttlecock, riding a hobbyhorse, playing a game of arrows, and putting on a puppet show. Most of the paintings deal with auspicious imagery often used in various art forms, being folk subjects favored at the New Year. The album bears no signature or seal of the artist, but it was probably done at the Ch'ing court.

Two of the children here ride a red and white hobbyhorse. Also some are carrying various mock weapons, such as a halberd and bow-and-arrow. One holds a hawk lantern as the others pull lanterns in the shape of a dog, rabbit, and deer, as if to suggest that they are out on a play hunting trip.

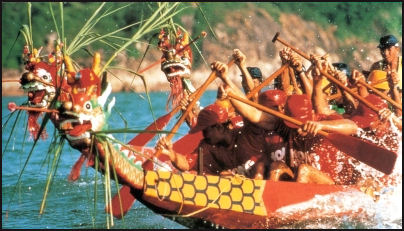

Dragon Boat Festival: Recognized by UNESCO

Dragon Boat Festival — Usually June — is held on the 5th day of the 5th lunar month. It honors a patriotic poet — usually Qu Yuan — who drowned himself in 278 B.C. in the Milou River, with the eating of zongzi (traditional glutinous rice cakes wrapped in bamboo leaves) and dragon boat races. The largest and grandest boat races are held on the Milou River and Yueyang in Hunan and Leshan in Sichuan. To honor Qu Tuan's death zongzi are wrapped in colorful silk are thrown into the river as an offering to the poet's spirit. The silk is used to keep away the flood dragon, who is afraid of silk. There are a number of rituals aimed at preventing floods. The festival tries to appease the god of the streams — the Dragon — so that rivers will not overflow their banks and cause floods.

The festival is celebrated all over the country, but in different ways. The Dai bang on their elephant leg drums and set off firecrackers. Korean women hold swing and seesaw competitions. In Guangxi there are men's and women's boating competitions in which no paddles are used (there is one race in which the participants use their hands and another in which they use their feet). At the end of each race in Leshan and in Zhangzhou and Xiamen in Fujian Province ducks are thrown into the water and the rowers jump in the water and try to catch them. The team and individuals that catches the most ducks get to keep them.

The Dragon Boat Festival was inscribed on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity list in 2009. According to UNESCO: Beginning on the fifth day of the fifth lunar month, people of several ethnic groups throughout China and the world celebrate the Dragon Boat festival, especially in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River. The festivities vary from region to region, but they usually share several features. A memorial ceremony offering sacrifices to a local hero is combined with sporting events such as dragon races, dragon boating and willow shooting; feasts of rice dumplings, eggs and ruby sulphur wine; and folk entertainments including opera, song and unicorn dances. The hero who is celebrated varies by region: the romantic poet Qu Yuan is venerated in Hubei and Hunan Provinces, Wu Zixu (an old man said to have died while slaying a dragon in Guizhou Province) in South China, and Yan Hongwo in Yunnan Province among the Dai community. Participants also ward off evil during the festival by bathing in flower-scented water, wearing five-colour silk, hanging plants such as moxa and calamus over their doors, and pasting paper cut-outs in their windows. The Dragon Boat festival strengthens bonds within families and establishes a harmonious relationship between humanity and nature. It also encourages the expression of imagination and creativity, contributing to a vivid sense of cultural identity.

Dragon Boat Festival Paintings

Describing a painting called “Chung K'uei on the Dragon Boat Festival” by Hua Yen (1682-1756, Qing Dynasty), the National Palace Museum, Taipei says: “ “Chung K'uei on the Dragon Boat Festival Hua Yen, a native of Fukien province, moved from Hangchow and settled in Yangchow to sell paintings for a living. He excelled at almost every subject, creating innovative compositions and lively forms. The painting is ink and colors on paper on a 131.5-x 63.7-centimeter hanging scroll. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei]

“In this work, Chung K'uei the Demon Queller wears a dark cap and a green robe as he sits leisurely in a chair viewing pomegranate and mallow blossoms in this garden setting. On the table are offerings of fruit, wine, and rice dumplings presented on the Dragon Boat Festival. In addition to the dragon boat regatta, this festival is also associated with expelling evil and pestilence (thought to occur on this, the fifth day of the fifth lunar month).

“Five demons are also shown here. One holds a tattered parasol, another brings a bowl of wine, and one has taken some fruit from the table. Caught by the demon behind, his cap was removed and head rapped as he reels back — thereby adding a humorous touch for which Hua Yen and other so-called "eccentric" artists in Yangchow were noted.

The fifth leaf of “Record of Annual Events and Activities by Wu Pin (fl. 1591-1643, Ming Dynasty "reflects the Dragon Boat Festival, which occurs on the fifth day of the fifth lunar month. One of the most important events is the Dragon Boat regatta, which people gather to view. Here, the dragon boats approach from the left as they race along under the bridge. Many shops here also show offerings of seasonal flowers, which was a common practice.

"Regatta on Dragon Lake" by Wang Zhenpeng

“Regatta on Dragon Lake” by Yuan Dynasty artist Wang Zhenpeng (fl. ca. 1280-1329) in an ink on silk handscroll, measuring 30.2 x 243.8 centimeters): According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: The seasonal custom whereby "each and every family celebrates Duanwu on the fifth day of the fifth lunar month" has a history in China spanning almost two millennia, with dragon boat races being the premier event of this festival, also known as the Double Fifth or Dragon Boat Festival. Many people do not realize, however, that back in the Northern Song period, the dragon boat regatta was an imperial activity actually taking place in the third lunar month. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

The term for "dragon boat" in Chinese appeared as early as The Tale of King Mu, Son of Heaven from the Warring States period, and that for "regatta" not found until later in the Jin dynasty with Zhou Chu's Record of Customs and then Record of Seasonal Events in Jing and Chu after that. Moreover, it was not until the Tang dynasty, with the works of such poets as Luo Binwang and Liu Yuxi, do the terms "dragon boat" and "regatta" appear together to represent the dragon boat rowing competition now associated with this festival. \=/

Records indicate that in the third month of 992, third year of the Chunhua reign, the Northern Song emperor Taizong took a tour of Lake Jinming and enjoyed water festivities there designated as a regatta. Thereafter, a dragon boat regatta was held in the third month of each year, eventually becoming a custom. By the middle of the Northern Song, celebrations for the third month regatta increased to include many activities, such as swinging and puppetry on the water, making the event even more raucous. In 1147, during the following Southern Song, Meng Yuanlao, in his recollection of life from the old days at the Northern Song Eastern Capital of Bian (modern Kaifeng, Henan), left behind a detailed account of the third month regatta at Lake Jinming in his Record of Dream Splendors at the Eastern Capital. \=/

“In the collection of the National Palace Museum are four handscroll paintings dealing with similar subject matter and all ascribed to the master of Yuan dynasty ruled-line painting, Wang Zhenpeng (fl. ca. 1280-1329). Despite perhaps being an imitation from after the Yuan, Wang's "Regatta on Dragon Lake" selected for this exhibition depicts regatta activities that find a close parallel with the record of old times in Record of Dream Splendors at the Eastern Capital. While admiring this handscroll painting, viewers can analyze the details of the exceptionally fine rendering and capture a tantalizing peek at the majestic sight of the dragon boat regatta once held at the Northern Song capital in the third month. \=/

Wang Zhengpeng (style name Pengmei), a native of Jiading (modern Wenzhou), was the most important ruled-line painter of the Yuan dynasty. According to the inscription at the end of this scroll, it depicts the dragon boat races at Lake Jinming held in the Chongning reign of the Northern Song on the third day of the third month, with all the people joining in joyous activities. The front of the scroll depicts a large dragon boat majestically escorted by four dragon- and tiger-head boats with fluttering pennants. In the middle of the lake is a palace and platform area connected to a bridge, with such activities as swinging and a puppet show taking place on the water. The palatial Baojin Tower stands at the end of the scroll towards the left as twelve dragon and tiger boats with people beating gongs and rowing as they race towards the goal pole. With pennants fluttering and paddles in motion, one can also almost hear the sound of the gongs here, the grand dragon boat race being most beautifully described. Nevertheless, due to questions about the authenticity of the inscription and accompanying seal impressions, this scroll may actually be a copy from after the Yuan dynasty.

Qixi (Chinese Valentine's Day, Double Seven Day)

Qixi — Chinese Valentines Day — falls on the seventh day of the seventh Lunar month, which is usually sometime in August. The holiday is based on the myth about the 7th daughter of the Emperor of Heaven who falls in love with an orphaned shepherd boy and then is banished to the star Vega by her father and is allowed to meet shepherd boy, who has been banished to the star Altair, only once a year — on the 7th day of the 7th lunar month. According to another variation of the Qixi Festival fairy tale the young shepherd falls in love with a beautiful weaver girl who is also the youngest daughter of the Empress of heaven. The shepherd and the weaver girl secretly marry. When the angry Empress finds out she draws a line between them that becomes the Milky Way. The only time they can get together is on held on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month.

Couples typically celebrate Qixi by dining out at fancy restaurants. These days many young singles attend match-making events specifically organised for under-25s. On Qixi in 2011 more than 4,250 couples registered their marriage. The figure was 10 times the daily average and was about 200 more than on Valentine's Day on February 14, according to the Beijing Daily, citing government statistics, Western Valentine's Day, known as Lover’s Day, is celebrated by many young urban people in China. Young men take out their girlfriends or prospective girl friends on big, expensive dates. Flower sales are brisk. Many vendors double the price of roses and lilies during the Valentine's Day season. Many hotels ignore regulations and allow unmarried couples to stay in double rooms.

Describing a painting called “Test of Skill on the Double Seventh Day” attributed to Ch'iu Ying (ca. 1494-1552. Ming Dynasty), the National Palace Museum, Taipei says: “ “Double Seventh Day refers to the seventh day of the seventh lunar month. Also known as "Weaving Day" or "Women's Day," the most important activity was the test of skill at weaving. The annual meeting of the constellations known as the Cowherd and Spinning Damsel also take place on this day, so this day is now celebrated as Chinese Lover's Day. In the past, however, ladies would use colored thread and seven needles on that evening. In a garden, they would set up incense with offerings of fruit, flowers, wine, and needle and thread to pray to the Spinning Damsel in hopes of being her equal in skill. In the Sung dynasty (960-1279), a figurine was also offered on display. This work shows the skillful sewing activities of ladies along with needle and thread as well as offerings. The painting is ink on paper on a 27.9-x-388.3-centimeter handscroll. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei]

“This work was done in monochrome ink. The figures are elegant, but the brushwork appears somewhat weak, differing from the exquisitely fine style traditionally associated with Ch'iu Ying and hence only attributed to him. Ch'iu Ying, a native of Kiangsu, was a lacquer artist in his youth. Later, the painter Chou Ch'en recognized Ch'iu's skills and took him as a student. Ch'iu achieved fame for his figure and landscape painting, and he was so skilled at copying ancient works that they were confused with the originals. Ch'iu Ying's works were noted for both their academic and scholarly flair, so he became known as one of the Four Masters of the Ming.

Mid-Autumn Festival Lanterns in Hong Kong

Double Ninth Day

Double Nine Festival — September or October — celebrates the auspicious number “9" on the 9th day of the 9th lunar month. It is regarded as a good time to drink lots of alcohol. Describing a painting called “Activities of the Twelve Months: The Ninth Month” by Anonymous Court Painters (Qing Dynasty 1644-1911), the National Palace Museum, Taipei says: “ “Activities of the Twelve Months: The Ninth Month The Double Ninth (Yang) Day refers to the ninth day of the ninth lunar month. The number 9 is particularly "yang" (as in the concept of yin-yang, whereby yang represents vigor); the "yang" number three is multiplied three times (shown as 3 x 3, hence the alternate name Double Yang Day). [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei]

The activities associated with this day include ascending the heights, wearing dogwood, appreciating chrysanthemums, and drinking wine. These began as a form of superstition in the Han dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) to avert bad luck. It is said that in the Eastern Han, a man named Heng Ching from Ju-nan studied the arts of Taoism under Master Fei Ch'ang-fang. One day, Fei told Heng that on the ninth day of the ninth month, Ju-nan would experience a catastrophe. Fei told him to hurry home, wear dogwood, ascend to a high place, and drink chrysanthemum wine to avoid this disaster. Heng followed his master's instructions and took his family to the hills. When they returned home at dusk, they found that all the livestock and animals were dead. Thus, Heng-ching and his family averted this mysterious disaster. The painting is ink and colors on silk on a 175-x-97-centimeter hanging scroll.

“The superstition part of this tradition faded and, by the T'ang (618-907) and Sung (960-1279) dynasties, it became a time for scholars to gather, drink, view chrysanthemums, ascend to high places, and compose poetry. Thus, the foreground here in this painting is filled with chrysanthemums as scholars gather and bring them for viewing. Up in the hills, we see that scholars have come together with wine and food to view the scenery there.

Image Sources: 1) People celebrating, All Posters com Search Chinese Art; 2) Spring Festival travel mess, China Trends; 3) Lantern Festival, CNTO; 4) Others, Taiwan Tourism Office.

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2021