HUNDRED FLOWERS CAMPAIGN

Anti-rightist campaign As part of the effort to encourage the participation of intellectuals in the new regime, the Chinese Communist Party began an official effort to liberalize the political climate in mid-1956. Cultural and intellectual figures were encouraged to speak their minds on the state of CCP rule and programs. Mao personally took the lead in the movement, which was launched under the classical slogan "Let a hundred flowers bloom, let the hundred schools of thought contend." At first the party's repeated invitation to air constructive views freely and openly was met with caution. By mid-1957, however, the movement unexpectedly mounted, bringing denunciation and criticism against the party in general and the excesses of its cadres in particular. Startled and embarrassed, leaders turned on the critics as "bourgeois rightists" and launched the Anti-Rightist Campaign. The Hundred Flowers Campaign, sometimes called the Double Hundred Campaign, apparently had a sobering effect on the CCP leadership.

In April 1957, the Communist government briefly allowed public discussion of controversial issues and criticism of the government when Mao put forward the idea of "letting a hundred flowers bloom" in the arts and "a hundred schools of thought contend" in the sciences. In the Hundred Flowers campaign intellectuals were advised to contribute their opinions on national policy issues. They condemned corruption and criticized the Communist party monopoly on power. Even Mao joined in. In a rambling speech on the "The Correct Handling of Contradictions Among the People," Mao admitted that 15 percent or more of the Chinese population was hungry and he was not surprised that some people were "disgusted" by Marxist inefficiencies.

After only five weeks the government had second thought about the Hundred Flowers Movements and the concept of freedom of expression and launched the Anti-Rightist campaign. The Anti-Rightist Movement, which lasted from 1957 to 1959, consisted of campaigns to purge alleged rightists within the Communist Party both in China and abroad. The term "rightists" was largely used to refer to intellectuals accused of favoring capitalism over collectivisation.

In the campaign to suppress counterrevolutionaries in the 1950s, 2.4 million people were executed according to official figures. [Source: Wu Renhua, Yaxue Cao China Change, June 4, 2016 ++]

Websites and Sources Death Under Mao: Uncounted Millions, Washington Post article paulbogdanor.com ; Death Tolls erols.com ; Communist Party History Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Illustrated History of Communist Party china.org.cn ; People’s Republic of China: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Everyday Life in Maoist China.org everydaylifeinmaoistchina.org; Mao Zedong Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Mao Internet Library marx2mao.com ; Paul Noll Mao site paulnoll.com/China/Mao

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: REPRESSION UNDER MAO, THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION AND NIXON factsanddetails.com; MAO'S PERSONALITY CULT, LEADERSHIP AND MAOIST PROPAGANDA factsanddetails.com COMMUNISTS TAKE OVER CHINA factsanddetails.com; FAMOUS ESSAYS BY MAO ZEDONG AND OTHER CHINESE COMMUNISTS AS THEY TAKE POWER factsanddetails.com; EARLY COMMUNIST CHINA UNDER MAO factsanddetails.com; DEATH AND REPRESSION UNDER MAO factsanddetails.com; GREAT LEAP FORWARD: MOBILIZING THE MASSES, BACKYARD FURNACES AND SUFFERING factsanddetails.com; GREAT FAMINE OF MAOIST-ERA CHINA: MASS STARVATION, GRAIN EXPORTS, MAYBE 45 MILLION DEAD factsanddetails.com; TOMBSTONE AND RESEARCH OF THE GREAT FAMINE factsanddetails.com; CHINESE REPRESSION IN TIBET IN THE LATE 1950s AND EARLY 1960s factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: "The Tragedy of Liberation: A History of the Chinese Revolution, 1945-1957" by Frank Dikotter, describes the Anti-Rightist period. Amazon.com; "Life and Death Are Wearing Me Out" by Mo Yan (Arcade,2008), s narrated by a series of animals that witnessed the Land Reform Movement and Great Leap Forward Amazon.com; “Blood Letters: The Untold Story of Lin Zhao, a Martyr in Mao's China” by Lian Xi Amazon.com; "China Witness, Voices from a Silent Generation" by Xinran (Pantheon Books, 2009) is collection of oral histories from Chinese who survived the Mao period Amazon.com; "Tombstone" by Yang Jisheng, the first proper history of the Great Leap Forward and the famine of 1959 and 1961 Amazon.com; "Mao's Great Famine: The History of China's Most Devastating Catastrophe, 1958-62" by Frank Dikotter (Walker & Co, 2010) Amazon.com; . "Fanshen" by William Hinton is the classic account of rural revolution during the communist-led civil war in the late 1940s Amazon.com; "Mao; the Untold Story" by Jung Chang and Jon Halliday (Knopf. 2005) Amazon.com; “Mao Zedong” by Jonathan Spence, Alexander Adams, et al. Amazon.com; "The Private Life of Chairman Mao" by Dr. Li Zhisui (1994) Amazon.com; “Mao Zedong: A Political and Intellectual Portrait” by Maurice Meisner Amazon.com; "Mao's New World: Political Culture in the Early People's Republic" by Chang-tai Hung (Cornell University Press, 2011) Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 14: The People's Republic, Part 1: The Emergence of Revolutionary China, 1949-1965" by Roderick MacFarquhar and John K. Fairbank Amazon.com

Background of the Hundred Flowers" Campaign

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “By 1956 the People’s Republic of China had completed the transition from a capitalist, market economy to a planned socialist economy. In making that transition, China had followed the Soviet model of economic development and socialist economy: five-year plans, a capital-intensive emphasis on the development of heavy industry, and an elitist educational and managerial system which rewarded technicians, engineers, and Party bureaucrats. However, agricultural production did not increase at the rates required by the economic planners, which in turn slowed the growth of industrial production. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“In this context, Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong (1893-1976) decided to call upon intellectuals to voice their criticisms. On February 27, 1957, Mao delivered a speech before the Supreme State Conference in which he encouraged criticism, using the phrase “let a hundred flowers bloom and a hundred schools of thought contend.” Intellectuals were at first reluctant to speak out, but by May 1957 they were convinced that they had official permission to do so. The following documents are a sample of the kind of criticisms that Chinese intellectuals raised in May-June 1957.

Opinions and Ideas from the Hundred Flowers Period (1957)

During the Hundred Flowers Period, the editor of Literary Studies said: “No one can deny that in our country at present there are still floods and droughts, still famine and unemployment, still infectious disease and the oppression of the bureaucracy, plus other unpleasant and unjustifiable phenomena. … A writer in possession of an upright conscience and a clear head ought not to shut his eyes complacently and remain silent in the face of real life and the sufferings of the people. If a writer does not have the courage to reveal the dark diseases of society, does not have the courage to participate positively in solving the crucial problems of people’s lives, and does not have the courage to attack all the deformed sick, black things, then can he be called a writer? [From a factory manager:] Learning from the Soviet Union is a royal road; but some cadres do not understand and think that it means copying. I say if we do, it will paralyze Chinese engineers. … I have been engaged in electrical engineering for twenty years. Some of the Soviet experiences simply do not impress me. Of course, I suffered a good deal in the Five.Anti movement [against private business and business leaders] because of these opinions.” [Source: “Sources of Chinese Tradition: From 1600 Through the Twentieth Century”, compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary and Richard Lufrano, 2nd ed., vol. 2 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2000), 466-468; Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

A writer said: “I think that Chairman Mao’s speech delivered at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art consisted of two component parts: one was composed of theories of a tactical nature with which to guide the literary and artistic campaigns at the time, the other was composed of theories involving general principles with which to guide literary and artistic enterprises over the long run. Owing to the fact that the life these works reflected belonged to a definite period and that the creative processes of the writers were hurried and brief, the artistic content of these works was generally very poor, and the intellectual content extremely limited. If we were to use today the same method of leadership and the same theories as were used in the past to supervise and guide writers’ creative works, they would inevitably perform only the function of achieving “retrogression” rather than progress.

See Intellectual Opinions from the Hundred Flowers Period (1957) [PDF] afe.easia.columbia.edu

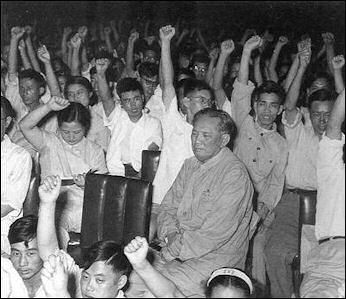

May reading Hundred Flowers comments

Anti-Rightist Movement in China

In the Anti-Rightist campaign 300,000 to 600,000 intellectuals were labeled as rightists, their jobs were taken away and many were sent to labor camps with their candid Hundred Flowers comments used as evidence against them. Mao said later he was trying to coax snakes out of their dens so he could chop off their heads. The term "rightist" — as in the opposite of "leftist" — sometimes included critics who, ironically, saw themselves as being to the left of the government, but officially referred to intellectuals who appeared to favour capitalism and were against socialism.

In the Anti-Rightist Campaign the Communist Party went on a nationwide witch hunt for supposed liberals, reactionaries and capitalist roaders. Some of those attacked were Chinese intellectuals who expressed their opinions on national policy issues under Mao's Hundred Flowers Campaign. The aim of the movement was aimed at “reform” anti-communist elements in the Party and society, which operated in disregard of the procedures, rules of law, and even the touted moral truths of the Party itself.

Frank Dikotter, Chair Professor of Humanities at Hong Kong University, told the South China Morning Post that in his book, The Tragedy of Liberation: A History of the Chinese Revolution, 1945-1957, he estimates the number of people persecuted during the Anti-Rightist Movement to be at least 550,000 and possibly more than 650,000.

Oliver Chou wrote in the South China Morning Post: “Around 550,000 so-called "rightists" were accused of "launching a ferocious offensive" on the Communist Party during the fateful summer of 1957. Instigated by Mao Zedong, the campaign followed seemingly genuine calls by the leadership for criticisms that might help to "rectify the party". For nearly two months, discussions were organised at work units across the country and criticisms put on record. Then Mao pounced, calling his tactics "an overt conspiracy" that lured "the snakes out of their holes". [Source: Oliver Chou, South China Morning Post, December 4, 2012]

"The ensuing anti-rightist campaign set the tone for the young People’s Republic and changed forever the lives of all those forced to put on a "rightist hat". Harvard University professor Roderick MacFarquhar, in his three-volume series The Origins of the Cultural Revolution, argues that the 1957 campaign led directly to subsequent politically motivated campaigns, including the Great Leap Forward, during which at least 20 million people were killed, and the decadelong Cultural Revolution, in which perhaps as many died and millions more suffered.

The repressive politics of the Cultural Revolution was in fact honed during the 1950s during the Anti-Rightist movement. One man who was forced to denounce his father as a counterrevolutionary during the anti-rightist campaign told the Washington Post, “My mother was forced to take me to a criticizing session. She taught me several words and asked me say them on the platform. I repeated the words and got enthusiastic applause.”

Some rightists have managed to rehabilitate themselves — retired premier Zhu Rongji and former minister of culture Wang Meng, a famous writer, among them. But for most of the 10,000 to 20,000 who are still alive around the world, the scars remain raw — for them and their families, The Anti-Rightist campaign remains difficult to research because of continuing censorship. Chinese historians say this is partly because of the central role in these ideological purges played by Deng Xiaoping.

Beginning of Anti-Rightist Movement

In a 1957 landmark address: “On the correct handling of contradictions among the people”, Mao urged unity among the nation’s disparate sectors was made in the wake of the Hungarian Incident of 1956, an early climax of Eastern Europe’s rebellion against the Communist yoke. In China too, intellectuals were beginning to have misgivings about the dictatorial rule of Mao and his comrades. By and large, Mao proposed reconciliatory measures to iron out differences among social groupings. He indicated that while there were signs of disaffection with the authorities, these were “contradictions among the people” because even oppositionists shared “the fundamental identity of [all] the people’s interests.” He recommended that the CCP “use the democratic method of persuasion and education” to woo the disgruntled elements. [Source: Willy Lam, China Brief (Jamestown Foundation), October 8 2010]

In his 1957 address, the Great Helmsman made a distinction between contradictions among the people and “contradictions between enemies and ourselves.” While Mao advocated “the democratic method of persuasion and education” with regard to critics who shared the CCP’s ideals, he indicated that so-called people’s foes — unreconstructed capitalists and “exploiters” as well as elements bent on sabotaging the socialist order’should be put behind bars or otherwise liquidated. It seems evident, however, that the late chairman often lumped together these two types of contradictions in accordance with political expediency. Just a few months after his “contradictions” speech, Mao launched the infamous “Anti-Rightist Movement,” one of Communist China’s harshest campaigns against liberal intellectuals. Victims of the movement included early advocates of free-market reforms such as former premier Zhu Rongji (Eastasiaforum.org, October 1, 2009; Washington Post, July 18, 2007).

Anti-Rightist Campaign

In the ensuing frenzy, half a million people were denounced and sent to labor camps. Intellectuals were stripped of their Party membership and sent to camps and farms, where they did menial labor during the day and participated in “self-criticism meetings” in the evenings for three or four years.

Jianyang Zha wrote in The New Yorker: “Most of the “Rightists” were true believers and Party loyalists, and their ordeal drove many to depression, divorce, and suicide. The writer Wang Meng underwent a period of crushing self-doubt. He convinced himself that he deserved this retribution for the privileges he had enjoyed, and worked assiduously to redeem himself through hard labor. Carrying rocks and planting trees, he wrote later, improved his health, which had been delicate since childhood.” [Source: Jianying Zha, The New Yorker, November 8, 2010]

Frank Dikötter, author of "The Great Famine" told Evan Osnos of The New Yorker: After the launch of the Anti-Rightist campaign “Ferocious purges were carried out throughout the ranks of the party. From 1957 to 1962 several million cadres in the countryside were replaced with hard, unscrupulous elements who trimmed their sails to benefit from the radical winds blowing from Beijing. In a moral universe in which the means justified the ends, many of them were prepared to become the Chairman’s willing executioners, casting aside every idea about right and wrong to achieve the ends he envisaged.

The use of the word "the enemy" comes from Mao's famous 195 7speech, "On the Correct Handling of Contradictions Among the People", which instructed officials, when dealing with alleged offenders, to distinguish between two types of social contradictions: those "between the enemy and us" and those "among the people". The former were to be handled with the unremitting severity of dictatorship.

Victim of the Anti-Rightist Campaign: Pak Chit-Man

Pak Chit-man, who turned 80 in 2012, was one of 550,000 so-called "rightists" accused of "launching a ferocious offensive." "Nineteen fifty-seven was the year I got married," says Pak, who made a living as a piano teacher in Hong Kong after having left Beijing in 1982. "I was 24, and Chiu Ling-ming, my wife, was three years younger. "We picked August 1, Army Day, for our wedding, because we loved the party and the People’s Liberation Army. By then I had already heard something was going to happen to me. But I believed in justice and thought I had nothing to fear," he says. [Source: Oliver Chou, South China Morning Post, December 4, 2012 ==]

Oliver Chou wrote in the South China Morning Post: “Within days, Pak, then the principal clarinettist of the Central Philharmonic Orchestra, the country’s top ensemble, was accused of "stirring up a general strike". The charge was based on a comment he made after he posted a letter on a wall asking the orchestra’s party cell to respond to a complaint of his. "It was in the canteen and I casually said, “If there is no reply by next week, let’s quit.” That turned out to be proof of my rightist deeds. To make matters worse, the person in charge of my case was an orchestra colleague whom I had turned in for misbehaviour a few years earlier. So my fate was fixed," Pak recalls. "Many marriages ended in divorce because of a rightist indictment," says Chiu. "Many people advised me to leave Pak for another man, given my young age. But I knew who I was with and stayed with him regardless." ==

“Pak was stripped of his orchestra duties, albeit temporarily. "I was sent to a Beijing suburb for a few months of labour in the fields," he says. "That was a relatively light sentence; I think they needed me in the orchestra because of a lack of clarinettists. The USSR State Symphony Orchestra was about to arrive, and the 10th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China was forthcoming and there were a lot of official concerts to show off the achievements of New China. ==

"But whenever a political campaign was on the horizon, we rightists would be the first to get hit. I often spent time in the fields or in the coal mines and, in 1959, refining steel, after Chairman Mao called on the nation to overtake Britain and the United States in steel production." It was while he was working at a steel factory on the outskirts of the capital that Pak and Chiu’s first child was born. "I was in my early 20s and I was all by myself in Beijing, and knew nothing about childbirth," says Chiu, who is the youngest of four siblings from a Chongqing family. "It was near dawn when I went into labour and I packed a few things and took a bus to the hospital. Ling was born a few hours later," she says. Pak wouldn’t see his daughter for a month. "I still feel very bad for not being with Ling-ming during the delivery. ==

“When I arrived home, it pained my heart to see my baby girl for the first time," Pak says, his eyes moist with tears. Pak named the child Ling, after the first character of his wife’s given name. When the couple’s second child, a boy, was born, in 1966, Pak had once again been put to work away from home. "When I arrived from Lantian, Shaanxi province [where he’d been involved in a “socialist education campaign”] in the summer of 1966, Ming was already three months old," he says. "Ming" came from the second character of his wife’s given name." ==

Victim of the Anti-Rightist Campaign: Chang Wing-Tin

Oliver Chou wrote in the South China Morning Post: “If Pak considered his A light sentence, colleague Chan Wing-tin was not so lucky. In 1957, the oboist heeded the party call and joined in the criticisms by accusing the orchestra’s general office of factionalism. "Those people were prejudiced against some of us, and I spoke on behalf of my buddies, exposing to the party the injustice we saw in the administration. After all, to help rectify the ranks is what we were asked to do," Chan, now 81, recalls. [Source: Oliver Chou, South China Morning Post, December 4, 2012 ==]

“His comments were used to "prove" he was attacking the party and he, also, was labelled a rightist. He was downgraded by two ranks, which meant a lower salary (it fell from 98 yuan to 72.50 yuan per month) and fewer benefits. He was stripped of his Communist Youth League membership and sent to serve in the northern-most labour camp, in Heilongjiang province, which borders Russia. He would be apart from his wife and infant daughter for three years. "Beidahuang was the coldest and the most deserted part of China. The temperature could drop to minus-30 degrees Celsius and there was no heat whatsoever. There I was, at Farm 850, with more than 10,000 rightists from all sectors. There was a moment when I felt so hopeless I cried and screamed out loud, “Oh party, I have done nothing against you! I am innocent!” I think a part of me died there," Chan says. ==

“When the political climate thawed slightly, in 1960, Pak and Chan were told their rightist status had been repealed and they had been reinstated to the orchestra. However, Chan could no longer play many notes because he couldn’t stop his hands from trembling, after so many years spent in the bitter cold. Worse, the stigma remained; they became known as "reinstated rightists", and their children "reinstated rightist children". "We were second-class or even third-class citizens, and were looked down on by others, even after our rightist hats were removed," says Pak. "For example, I would never get to play the best instrument, but always a substandard clarinet." ==

"Our children faced prejudice as early as kindergarten, although they were too young to understand it," says Chiu. "But we as parents felt very bad. "The school was worried about being accused of providing a platform for rightist children, but Ling was the school’s best violinist. That often put the school in a dilemma," says Chiu, adding that the little girl would be forbidden from rehearsing for performances in which she’d be a soloist. ==

“Ling, who would go on to become a violinist with the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra for two decades, remembers little of that time."Even if there were unpleasant moments between me and the other kids, I was so little that I thought of it as normal," she says. Her brother, however, remembers. "My parents were very stern and always kept us inside," says Ming. "All we did was practise the violin and nothing else," recalls the former Hong Kong Philharmonic viola principal. "Father disciplined me in a very physical way, and I got beaten not by his hand but by the rod in his hand. Sometimes the bruise lasted a week. If the same thing happened today, someone would report it to the police," he says. ==

"I didn’t care about myself being badmouthed or despised, but not my children," says Chiu. "We kept them at home in fear that the other kids would bully them for being rightist children." "We adults were doomed and had no future, so we placed all our hopes on our children," says Pak. "That’s why, when they were lax in practising, I got very mad. But every time after I beat them, I felt very bad. "I think, without the rightist curse, I would have been more psychologically balanced." "His rightist verdict deprived him of peace of mind, and that’s why he was easily provoked and vented his anger on us," says Ming. "The lack of inner peace haunts him even now, and my daughter sometimes takes [a verbal assault] from the old man." ==

Victim of the Anti-Rightist Campaign: Yang Bao-Zhi

Oliver Chou wrote in the South China Morning Post: “For Yang Bao-Zhi, who was childless, it was his parents who would bear the brunt of his being labelled a rightist. "The year I was branded a rightist was the year I graduated from the Central Conservatory of Music, in Tianjin. My parents were senior staff there; my mother was with the primary school and my father was in charge of recordings and other reference sources at the library," the 77-year-old violin teacher and composer says. "As the eldest son and an active student — I was chief of military and sports at the student union — my rightist label came very hard for my parents. "I didn’t take it seriously at first, thinking the political wind would last a month at the most. But it turned out to be 22 years." [Source: Oliver Chou, South China Morning Post, December 4, 2012 ==]

“Yang was lucky; he was "rescued" by a visiting official from the Chongqing Municipal Song and Dance Ensemble, who recognised his talent and offered to "re-educate" him. "So I was freed from labour in the paddy fields and worked in the Chongqing ensemble, although that meant I had to leave my parents to go to the city." ==

"Shortly after he left, the family was dealt a second blow. Yang’s father was also branded a rightist, and was downgraded three levels. From his role as head of the library, he was demoted to being an ordinary staff member, and his salary dropped to 96 yuan from 128 yuan. "My father was very close to the conservatory director Ma Sicong, who, like us, was from Guangdong. I think we were protected by Ma, who was under fire himself. Although my mother was not directly affected and kept her senior position at the primary school, she was heartbroken to see two of the family of four branded rightists." ==

“Yang believes he was responsible for implicating his father, although the quota system whereby each unit of the workforce had to yield a certain number of rightists (generally understood to be 5 per cent) would have played a part."When the party invited criticism, I, as an activist, did say something critical about my father, and reported it to the Communist Youth League, of which I was a member to show my progressive attitude. No one knew how the turn of events would unfold, but it turned out most of the active members, including the league’s chief, would be labelled rightists. After that, everyone kept their mouth shut and did not trust anyone," he says. His parents were not angry with him, says Yang, but they did become very careful about what they said to him. That was to prove fairly easy, however; for almost five years Yang did not see them. It was not until 1962 that the family were reunited. By then, both father and son had had their charges dropped. ==

Survivors of an Anti-Rightist Prison

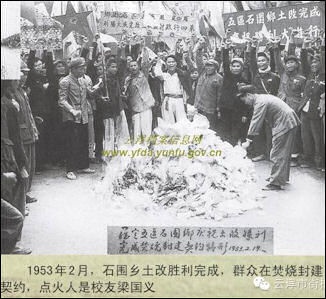

anti-rightist poster

Xianhui Yang’s "Woman From Shanghai: Tales of Survival From a Chinese Labor Camp" is a collection of firsthand accounts that the publisher calls fact-based fiction, Howard French of the New York Times called it the “Gulag Archipelago of China.” The stories, which he painstakingly collected over a three-year period a decade ago, are those of people branded by the Chinese state as rightists in the late 1950s and sent to Jiabiangou, a notorious camp for re-education through labor in the northwestern desert wastelands of Gansu Province. T he camp, which was originally built to hold 40 or 50 criminals, came to hold roughly 3,000 political prisoners between 1957 and 1961. All but 500 of them would perish there, mostly of starvation. [Source: Howard W. French, New York Times, August 25, 2008]

Common features of the survivor stories, French wrote, include “the exposure to bitter cold; hunger so intense as to cause inmates to eat human flesh; the familiar sequence of symptoms, beginning with edema, that lead down the path to death; the toolbox of common survivor techniques, from toadyism to betrayal, from stealthy theft to making use of the vestiges of privilege, which survived even incarceration in this era of radical egalitarianism.”

“The first few stories are so bleak that it is difficult to summon the emotional energy to continue reading, but if you do continue, you will be treated to small wonders of human kindness miraculously appearing in a hell only a tiny fraction of the prisoners survive,”Paul Foster of the Georgia Institute of Technology wrote in a review of the book. “The stories in Woman from Shanghai do not attack so much as they offer indirect socio-political critique; they are narrated in a straightforward manner, with only the slightest degree of accusation against individual perpetrators within the labor camp or against the leaders of the movement, and sometimes even defending the leadership.”[Source: Paul Foster, Georgia Institute of Technology, MCLC List Review, January 2010 ***]

“Woman from Shanghai may be read as a kind of primer of survival in a totalitarian state, describing tactics to physically (though not mentally or emotionally) endure the worst abuses of a repressive socio-political structure,” Foster wrote. “In a style that is at once heart-rending and instructional, these texts reveal that corruption and betrayal in the political and family structures are inevitable and that to survive an excruciatingly slow death one must fight “corruption” cleverly with “corruption” of one's own, by way of thievery and self-debasement.” ***

Book: "Woman from Shanghai, Tales of Survival From a Chinese Labor Camp" By Xianhui Yang, translated by Wen Huang (Pantheon Books, 2009).

Survivors’ Stories from the Anti-Rightist Movement

anti-rightist poster

“Related in a matter-of-fact tone,” Foster wrote, “the stories depict unimaginable and viscerally disgusting acts of self-survival: cannibalism, eating vomit, picking undigested food from animal feces, excavation of fellow prisoner's plugged intestines in desperate attempts to forestall death — acts usually described in the third person, though sometimes in the first. The stories' explanation of the simple mechanics of political persecution and family betrayal in the name of some greater social good — or perhaps just to fulfill a quota of bad elements to be reeducated at some work unit — portend the extremes later to be perpetrated during the Cultural Revolution, a dress rehearsal, as it were.” [Source: Paul Foster, Georgia Institute of Technology, MCLC List Review, January 2010 ***]

“The characters in the title story try to conceal the desecration of her husband's body from his wife. She has traveled far in hopes of seeing him, but discovers that he died a week before her arrival. Though the prisoners state that they do not know where he is buried, she insists on searching for his “grave,” and her persistence traps the prisoners in a web of lies about the treatment of the dead at the prison. While the title story and two other stories are told movingly, the relatively dispassionate narrative in which these stories are related in general may not be so surprising if one considers they are told by the lucky survivors, some of whom were subsequently targets of persecution during the Cultural Revolution because they had been labeled “Rightists” in this earlier campaign — they had learned to survive by suppressing their anger and not directly confronting the power structure.” ***

“The Love Story of Li Xiangnian" is the outstanding piece of this collection. It tells of how the handsome, educated, and outspoken Li had fine romantic prospects but for found himself declared a Rightist because his father had worked for the Nationalist government. Replete with narrative twists and turns as fine as any storyteller could weave, Li incisively describes not only his frame of mind vis-à-vis his accusers, the prison, and society, but also critiques the “lie” of the project to “reform your thinking through hard labor” (126). Li escapes, finds his girlfriend, then leaves her in order to protect her, but cannot count on support from his family, which had turned its back on him. He credits his survival to being thrown into a real prison: if had been sent back to Jiabiangou he “would have died of starvation” (135). Eventually Li tells of confronting his sister about his fear that she would turn him into the police, of how he searched out his former lover, and of their secretive reconciliation.” ***

Children at Anti-Rightist Labor Camps

Verna Yu wrote in the South China Morning Post, “When Xie Yihui read about the deaths of many children in a Sichuan "re-education through labour" camp in the early 1960s, she was horrified. She had been reading an account by Zeng Boyan, a retired journalist and former camp inmate, who wrote of his disbelief in 1958 when he saw about 200 children as young as 10 from the Dabao labour camp working in a forest near the Shaping state-run farm, where he was held as a "rightist". Years later, a witness who helped bury dead children told him that some 2,600 children from Dabao had died mostly of starvation between 1960 and 1962. Xie said the government had never released the number of deaths at the camp. Moved by the piece, Xie decided to interview Zeng and two dozen former child labourers. Her work resulted in the documentary Juvenile Labourers Confined in Dabao. Xie was struck by what Zeng told her: "I could almost see this image in my head; several hundred little children labouring in the forest and chased by a supervisor with a whip."[Source: Verna Yu, South China Morning Post, May , 2013 ///]

“Juvenile labour and education centres were set up across the mainland in the late 1950s, based on the Soviet model where delinquents and street children were sent for reform. Witnesses said 5,000 to 6,000 children aged from nine upwards were sent to Dabao from late 1957 until its closure in 1962. Some were young offenders convicted of petty crimes, but many were sent by impoverished parents who believed that their children would fare better in an institution where they were promised food and education. But the children soon found out that food was scarce and lessons lasted only a few months. ///

Chinese prisoners

“Former child labourers, now mostly in their 60s, said they were forced to do hard labour such as transporting wood, clearing land and planting crops. Against the backdrop of the Great Famine (1958-1961), the hungry children ate anything they could find: earthworms, mice and poisonous plants. Many suffered from malnutrition, while others contracted fatal parasitic infections. "They [child labourers] lived like ghosts and there was no love and warmth in their lives," Xie said. “///

Film on an Anti-Rightist Labor Camp

Thousands of citizens, labeled “right-wing deviants” for their criticism of the Communist Party, were sentenced to forced labor in the Gobi Desert under conditions so inhumane that death from starvation, exhaustion or illness was the norm.

Wang Bing’s "The Ditch" ("Jiabiangou") — a film about human suffering at a re-education camp in the windswept Gobi Desert” premiered at the Venice Film Festival as the “surprise film” in the competition. Set in 1960, the film chronicles the conditions facing inmates accused of being right-wing dissidents opposed to China's great socialist experiment, condemned to digging a ditch hundreds of miles long in the dead of winter. Famine stalks the camp, and soon death is a daily fact. [Source: Gina Doggett, AFP]

Wang told AFP, “It's a film that brings dignity to those who suffered and not a “denunciation film or a protest film.” “We wanted to preserve the memories, be aware of the memories, even painful ones.” As Wang was born in 1967, the events “took place before my birth, so I put in great effort to understand the 1950s and 1960s in China, to understand the historical truth.”

Justin Chang wrote in Variety of "The Ditch": “this powerful realist treatment offers a brutally prolongedimmersion in the labor camps where numerous so-called dissidents were sent in the late 1950s. Result makes for blunt, arduous but gripping viewing that will be in demand at festivals, particularly human-rights events, and in broadcast play.” Wang Bing’s previous efforts are ”Fengming: A Chinese Memoir“, his three-hour epic documentary about China's “anti-rightist” campaign, and nine-hour “ West of the Tracks “. [Source: Justin Chang, Variety]

Chang wrote: “”The Ditch“ makes only glancing reference to the political events that precipitated the anti-rightist movement, and the film's minimal context and thinly sketched characters could be read as a broad condemnation of atrocities and abuses perpetrated in any country... Set over a three-month period in 1960, at the Mingshui annex of Jiabiangou Re-education Camp, the film observes as a new group of men arrive, are assigned to sleep in a miserable underground dugout (euphemistically described as “Dormitory 8') and begin the long, slow process of dying. The work is intense, but hunger is the prisoners' chief struggle as well as the film's main preoccupation. Rats are eaten as a matter of course, consumption of human corpses is not unheard of, and, in the most stomach-churning moment, one man happily helps himself to another's vomit. Eating seems a compulsion rather than a sign of any real will to survive, and new bodies are dragged out daily, making room for fresh arrivals.”

“Drawn from a novel by Yang Xianhui and interviews Wang conducted with survivors (one of whom, Li Xiangnian, is credited with a “special appearance” as one of the prisoners), the film has an overpowering feel of unfiltered reality that persists even as tightly framed dramatic moments begin to emerge. Admirers of Wang's documentaries know his ability to capture real moments of extraordinary intimacy, and the sense of verisimilitude here is so strong that those walking in unawares may at first think they're watching another piece of highly observant reportage — never mind that no filmmaker would ever have been granted access, just as no humane documentarian could have kept the camera rolling without offering his subjects a scrap of food at the very least.”

“The film eventually comes to center on the friendship between two men, Xiao Li (Lu Ye) and Lao Dong (Yang Haoyu)... The second half is almost entirely unmodulated in its portrayal of suffering, and the illusion of realism Wang has conjured falters a bit... Dramatically, “The Ditch” is as arid and unrelenting as the setting it depicts, and its commingling of anguish and anger is far from subtle. But this may be the only way to properly dramatize and empathize with these men's experience; if barely two hours seem unendurable, three months defeat the imagination.”

Dead Souls

“Dead Souls” Wang Bing’s nine -hour documentary got a small-scale arthouse release in Paris in 2018. Sebastian Veg, a Professor of Chinese History in France, wrote in his blog: “Dead Souls is a project Wang Bing has been working on for over a decade. When Yang Xianhui’s book Chronicles of Jiabiangou (a collection of lightly fictionalized oral history accounts of former victims of the Anti-Rightist movement in Gansu who survived the deadly famine in the Jiabiangou Reeducation Through Labor Camp in 1960), Wang Bing contacted Yang. Wang Bing is from rural Shaanxi, which borders Gansu and, as he has mentioned in interviews, two of his uncles on his father’s side were persecuted as rightists, which may have sparked his interest in the book. After buying the film rights to Yang’s book, Wang Bing proceeded to start seeking out the people Yang had talked to, conducting his own interviews with them. [Source: Sebastian Veg Blog, November 25, 2018]

One of these interviews with He Fengming, who had written a book explaining how her husband Wang Jingchao died of famine in Jiabiangou, became a stand-alone film, Fengming (2007). These interviews were preparations for a fiction film project, which was finally completed in 2010 under the title The Ditch. Shot in harrowing conditions more or less on location, it uses what I argued was a form of highly theatrical acting to create a sense of distance between the viewer and the story. Since that time, Wang Bing has mentioned that he had plans to use the footage of the 120 preparatory interviews to make a kind of compendium documentary on the Anti-Rightist movement. This is the project that has now partially come to fruition (Dead Souls is supposed to be the first part of a several-part project). Wang Bing struggled for many years with this material to the point of mental anguish and only managed to overcome the difficulties after going back to Lanzhou in 2014 and re-interviewing those of the survivors who were still alive. He has stated that observing the speed at which their ranks were thinning gave him a sense of urgency that helped him finish the film.

“Before discussing the film itself, I want to mention another unique work: Traces (2014). As Wang Bing has explained, this 29-minute documentary was shot during his first visit to the site of Jiabiangou, using old 35 mm film that he had collected for some years. During most of the film the camera points straight down to the sandy desert ground, occasionally showing the director’s boots. In the first section “Mingshui,” wherever the camera turns, it finds human bones, loosely scattered among the sand, and even several skulls, as well as some more recent remains of bottles, gourds and clothes left by vagrants. In the second section “Jiabiangou,” the camera enters some of the caves where the inmates lived in 1959-1960. “The film has a strong self-reflexive dimension. Some of the old 35 mm film is corrupt, so that geometrical shapes appear on the image.

“Dead Souls is divided into three parts (it was shown in Cannes in two parts). Of course, the main challenge in organizing the massive amount of footage (600 hours) was how to structure the film. The excellent press kit contains an interview in which Wang Bing explains that, rather than a chronological organization, he chose to give each surviving witness a block of roughly 30 minutes. Of course, this time represents only a fraction of the full interview, and Wang Bing uses exaggeratedly rough jump cuts to draw the viewers’ attention to what he is leaving out, almost like ellipsis marks in a quotation. All together, there are a dozen of these long testimonials in the film. Just like in Yang Xianhui’s book, almost all of the interviewees underscore that they had no political divergence with the communist party, they were not “rightists,” but were usually targeted for extremely minor and mundane offenses.

“While I can’t provide a full discussion of the film here, I’d like to mention two episodes that stand out very strongly. In the first part, a long sequence is devoted to the funeral of one of the survivors whom Wang Bing has briefly interviewed on his sickbed, Zhou Zhinan. A traditional burial with instruments and ritual lamentations, in the remote hilly countryside of Shaanxi (whereas the government aggressively promotes cremation as the only “modern” type of burial) in December 2005, it shows the abiding sadness and resentment of Zhou’s son who tries to lay his father to rest while honoring the memory of his persecution.

“Another outstanding episode appears in the third part of the film, with the only interview of a camp guard, Zhu Zhaonan. Wang Bing notes that guards were often older and many have already died, while others are not willing to speak out. It is also the only interview in which the director is visible. Zhu was a cook in Jiabinagou, who was sent ahead to set up the annex at Mingshui, where the greatest number of inmates ended up dying. Listening to Zhu’s narrative, suddenly all the parts of the camp’s geography and organization fall into place, as we realize how fragmented the vision of each survivor is, and how little they understood about the camp as a whole. Zhu provides fascinating details, such as the fact that in the main camp they provided halal food for Muslim rightists. He quantifies the deeply felt inequalities in treatment between cadres and inmates: cadres were given about 450g of grain per day, while the inmates’ ration was 250g. Mingshui was organized around three ditches in which the inmates lived. As everything broke down in Mingshui during the massive famine, deaths were still generally logged in the record books but the dead could no longer be buried because the ground was frozen at least one meter deep. Death was everywhere and became completely normal. The authorities wanted the rightists dead: “ .

“Sympathizing with the rightists was out of the question because of “class consciousness,” even though many of the guards knew that they had been falsely accused or deported on trumped-up charges. Zhu prides himself on having at least tried not to mishandle anyone. The interview ends with the only known surviving photo of Jiabiangou, which Zhu gave to Wang Bing when they met again. It shows him riding a bicycle smiling amid a bunch of bedraggled inmates, and is a truly chilling testimonial to what in effect became a death camp, reminiscent of controversies surrounding photos of Nazi concentration camps. This is underscored in the ending of the film, which concludes with the footage of the camera nosing among the bones scattered in the sand.

Anti-Rightists Become Targets Again in the Cultural Revolution

anti-rightist activities

Oliver Chou wrote in the South China Morning Post: “In 1966, Mao initiated the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, which lasted for a decade, until his death. The five categories of people targeted first were landlords, capitalists, counter-revolutionaries, criminals and rightists. So Pak, Chan and Yang once again became targets, to varying degrees (in fact, many of the rightists who had survived up to then suffered less during the Cultural Revolution, perhaps because they had been mentally toughened by past experiences). "We were the targets of surveillance and, in the official language, “put into use under supervision," says Chan.[Source: Oliver Chou, South China Morning Post, December 4, 2012]

‘Since the Central Philharmonic Orchestra was designated a "model troupe", enlisted as part of the People’s Liberation Army with Jiang Qing, better known as Madame Mao, as its boss, Pak and Chan had some level of protection. "Jiang came to hear us play late one evening," says Chan. "She wanted to check the sound of each instrument and, when it was my turn, I played her a tune on the English horn. The next morning, she arranged for us to hear a Peking opera with a modern theme, and that became our signature revolutionary symphony, titled Shajiabang."

Says Pak: "There was one performance at the Great Hall of the People, for which the entire orchestra rehearsed in the morning. When we were all waiting in the van in the evening, with our instruments, in our outfits and ready to go, a guy came on board and asked me to leave. There was no reason given but I suspect my rightist background made me persona non grata. So, in front of everyone, I, in full uniform, left the van. That’s the way they liked to inflict insult."

“In Chongqing, Yang endured insults hurled at mass rallies and, forbidden from teaching "for fear of poisoning the young", he was demoted to instrument repair man and stage janitor. "My parents were very fortunate to have moved back to Guangzhou in 1965, just before the Cultural Revolution," he says, adding, "That was a life-saver. For me, life in Chongqing was definitely safer than in Beijing.

"As I tuned the violins I was working on, I played every now and then a tune of my own composition, including those using avant-garde techniques. No one could tell the difference between tuning and the playing of those works anyway."No one, that is, except a teenage boy who watched and listened. From 1971 to 1976, Guo Wenjing practised his violin and studied composition with Chongqing’s only Central Conservatory graduate. "Yang Bao-zhi is my mentor and I learned music from him," says Guo, now professor of composition at Yang’s alma mater and described by The New York Times as "perhaps the only Chinese composer who has established an international career without having lived outside China for an extended period."

Anti-Rightists After the Cultural Revolution

anti-rightist poster

Oliver Chou wrote in the South China Morning Post: “With the arrest of Madame Mao and the rest of the Gang of Four in 1976, the Cultural Revolution came to an end. As China emerged from the turmoil, there were a lot of old scores to settle. The party issued the 11th and 55th documents in 1978 to "restore those incorrectly indicted" for being rightists. Both Pak and Chan received copies of the 1957 files detailing their "wrongdoing", which had been redefined as "proper" and "in accordance with democratic principles".[Source: Oliver Chou, South China Morning Post, December 4, 2012]

"At least we were real rightists," says Pak. "I heard of cases where individuals had been branded as rightists but the authorities failed to find the original file with the charge, or produced a file that was totally blank. In other words, they had suffered for 20 years without an official verdict. "Some did not live to find that out. You can see how absurd the whole thing was."

“In 1979, Yang’s case was closed. The Central Conservatory personnel office returned his file, stating that the remarks he made in 1957 were "neither anti-party nor anti-socialism". But it was not until 1984 that he returned to his alma mater in Beijing, where he resumed teaching the violin and research before moving to Hong Kong in 1995."My father was from Hong Kong, and I attended Pui Ching Primary School in the 1940s. So, after some 40 years, I was glad to make it back here and focus on my violin composition and teaching, undisturbed," he says, from his new Sha Tin home, which he shares with his wife.

“Pak and Chan have lived in Hong Kong since the early 1980s. Pak continues to coach piano students and Chan chairs at least four organisations that promote cross-border cultural exchange. Chan’s son and daughter have settled overseas, his wife having joined the latter in Los Angeles. Pak’s daughter lives in Hong Kong but his son, Ming, has returned to teach in Beijing, where the story of rightists began 55 years ago. "The scene of the freezing cold still haunts me in nightmares," says Chan, in a later interview. "I had a very bad dream the day I told you my story, "I guess once you are a rightist, you’re always a rightist. It stays with you for life."

“No Persecution” in the Anti-Rightist Movement

Making anti-rightist posters

In May 2013, Amy Li wrote in the South China Morning Post, “China’s intellectuals, scholars and bloggers were outraged after Li Shenming, a vice director at the China Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), claimed that “not a single person" was persecuted during the infamous Anti-Rightist Movement launched by Mao Zedong in 1957. The remark appeared in an article titled “Appropriately evaluating the periods before and after China’s reform and opening-up”. It was published in the Party theory journal Seeking Truth. In a lengthy essay, the former secretary to Wang Zhen, one of China's revolutionary commanders who was well-known for his hard-line political views before his death in 1993, enthusiastically defended Mao Zedong’s leadership and economic and political “accomplishments”. [Source: Amy Li, South China Morning Post, May 14, 2013 :::]

“Li also blasted the "unbalanced media reporting" on Mao's movement. He wrote, “In the 1957 Anti-Rightist Movement, 550,000 were labelled as rightists, but not a single person was persecuted. However, the [movement] was described as a bloody one by media controlled by international capital.” The remark was greeted by thousands of angry comments from both scholars and grass-roots bloggers. :::

“Although controversy surrounds the actual number, many believe hundreds of thousands were persecuted or tortured to death during the movement. “There are two kinds of people in CASS, those who pretend to be stupid and those who are,” wrote a blogger. "Stop lying," wrote many others. "What do you receive for spreading such lies?" :::

Image Sources: Everyday Life in Maoist China.org everydaylifeinmaoistchina.org; Ohio State University, Wiki Commons, Laogai Museum

Text Sources: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2016