QING DYNASTY ART AND CRAFTS

Kangxi-era wood water container

Art produced during the Qing period was particularly ornate. Incorporating Tibetan, Middle Eastern, Indian and European influences, it included elaborately carved wood, baroque ceramics, heavily embroidered garments, and intricately worked gold and rhinoceros horn. Among the more extravagant pieces of Qing art are silk costumes made with applique embroidery; a royal hat made of sable, silk floss, gold, pearls and feathers; and a five-foot-high cloisonne elephant with a lamp on its back.

Holland Cotter wrote in the New York Times: “What the Qing wanted in court art was more: more ingenuity, more virtuosity, more bells and whistles, extra everything. When it came to scale, they went for extremes, the teensy and the colossal, cups the size of thimbles, jades the size of boulders. The Confucian middle way was not their way.”

Qing art included large-scale portraits, silk robes, painted screens, handscrolls, headdresses, fans, bracelets and furniture. Some of the best art works were small. A 19th century hair ornament with dragons was decorated with pearls, coral, kingfisher feathers and silver with gilding. On a larger, Buddhist stupa made from gold and silver, Sebastian Smee wrote in the Washington Post: The stupa, which is adorned with coral, turquoise, lapis lazuli and other semiprecious stones, was commissioned by the Qianlong Emperor in honor of his mother, the Empress Dowager Chongqing, after her death. Inside is a box with a lock of her hair. The Qianlong Emperor micromanaged its creation, continually issuing new instructions, so that it ended up being twice as tall and far more elaborate than the original design. [Source: Sebastian Smee, Art critic, Washington Post, April 12, 2019]

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Qing Dynasty and Traditional Chinese Culture” by Richard J. Smith Amazon.com; “Splendors of China's Forbidden City: The Glorious Reign of Emperor Qianlong” by Chuimei Ho and Bennet Bronson Amazon.com; “Emperor Qianlong: Son of Heaven, Man of the World” by Mark Elliott and Peter N. Stearns Amazon.com; “Chinese paintings of the Ming and Qing Dynasties, 14th-20th century” by Edmund Capon and Mae Anna Pang Amazon.com; “Objectifying China: Ming and Qing Dynasty Ceramics and Their Stylistic Influences Abroad” by Ben Chiesa, Florian Knothe, et al. Amazon.com; "Forbidden City" by Frances Wood, a British Sinologist Amazon.com; “Chinese Dress: From the Qing Dynasty to the Present Day” by Valery Garrett Amazon.com; “Ruling from the Dragon Throne: Costume of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911)” by John E. Vollmer Amazon.com; Ceramics: “Chinese Ceramics: From the Paleolithic Period through the Qing Dynasty” by Laurie Barnes, Pengbo Ding, Jixian Li, Kuishan Quan Amazon.com “How to Read Chinese Ceramics by Denise Patry Leidy (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) Amazon.com; “Chinese Glazes: Their Origins, Chemistry, and Recreation” by Nigel Wood Amazon.com; Porcelain: “Illustrated Brief History of Chinese Porcelain” by Guimei Yang and Hardie Alison Amazon.com “Chinese Porcelain” by Anthony du Boulay Amazon.com; “Chinese Pottery and Porcelain” By Vainker ( Amazon.com ; Jingdezhen: “China's Porcelain Capital: The Rise, Fall and Reinvention of Ceramics in Jingdezhen” by Maris Boyd Gillette Amazon.com; “Jingdezhen Imperial Kiln Museum” by Zhu Pei Amazon.com; Art: “The Arts of China” by Michael Sullivan and Shelagh Vainker Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery” by Patricia Bjaaland Welch Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: (World of Art) by Mary Tregear Amazon.com; “Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei” by Wen C. Fong, and James C. Y. Watt Amazon.com ; “The British Museum Book of Chinese Art” by Jessica Rawson, et al Amazon.com; “Art in China (Oxford History of Art) by Craig Clunas Amazon.com

Imperial Workshops of the Qing Dynasty

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: China “reached unprecedented heights during the reigns of the early to middle Qing emperors Kangxi (1662-1722), Yongzheng (1723-1735), and Qianlong (1736-1795). Not only was the political scene in a state of exceptional calm, but arts and culture also saw improvements and innovations like never before. These three reigns were truly an age of peace and prosperity. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“As opposed to the late Ming, from the late 17th century onwards, the product economy of the common market and the private collections that they produced gradually infiltrated the households of officials and wealthy merchants, eventually trickling into the imperial household after the establishment of the Qing dynasty. As soon as he ascended the throne, the Kangxi Emperor established the Imperial Household Workshop in the Hall of Mental Cultivation, where myriad vessels were manufactured for imperial use. The institution and its arrangement persisted through the reigns of emperors Yongzheng and Qianlong. According to relevant historical sources, the imperial workshop systematically governed by the court rendered possible the formulation of a clear, standardized scheme of production. This included the design, model production, and presentation after completion, the emperor having the ultimate say in deciding where to display or store the pieces. His imperial orders were heeded and implemented without delay. Apart from the inner court, silk textile workshops were established in Suzhou, Hangzhou, and Kiangning to create an extensive production network.

“The craftsmen specializing in wood or ivory carving under the Imperial Household Administration of the early Qing carried heavy responsibilities. Experienced, skilled artisans from the masses were also recruited into the production staff, and they created masterpieces that inspired awe and praise among the imperial court. Illustrious craftsmen such as Ch'en Tsu-chang, Feng Ch'i, Huang Chen-hsiao, and Yang Wei-chan worked for the Qing emperor Qianlong, leaving behind breathtaking works of genius in the palace. Some of their most impressive work included Ivory carving of a dragon-boat in a lacquer case, 17th-18th, century; and “Olive stone with poem "Ode to the Red Cliff" carved on the bottom, mark and reign period of Qianlong, Qing dynasty, Qianlong reign 2nd year (1737).

Qing Era Jade

Jade pieces from the Qing imperial court were characterized by their impressive size, neatness and symmetry. Common motifs included dragons, emblems of the emperor, various auspicious symbols, and imperial inscriptions and marks. These jade pieces were often put on sandalwood pedestals or kept in special cases and boxes. During the early Qing Dynasty, jade from Xianjiang was carved into elaborate floral designs, shallow reliefs the thickness of paper and ornaments inlaid with colored glass or gold and silver thread. Jadeite carving really took off under the Qianlong Emperor, who preferred the varied translucent colors of jadeite to the opaque "chicken bone" jade and "mutton-fat" nephrite that was prized before him. Jadeite from the Yunnan Province and northern Burma were imported into China in large quantities in the 19th century and became prized above all other kinds of jade.

Interesting Qing Dynasty pieces (1644~1911) include 1) “Jadeite Squirrels and Grapes, on a wood stand (7.2 centimeters high and 5.1 centimeters wide); 2) “Jade Boy and Bear: (6.0 centimeters tall); 2) “Agate Tobacco Powder snuff Bottle with a ferrying scene; 3) “Agate Tobacco Powder snuff Bottle with a ferrying scene (5.1 centimeters wide; 5.9 centimeters tall); and 4) “Agate Tobacco Powder snuff Bottle with a scene of triumph” (5.3 08 wide; 6.7 centimeters tall)

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei : Jadeite Screen Insert was one of the most representative screen types found at the Qing dynasty court. It is a kind of screen with a stand, in which the base and the screen frame together form a whole. A groove is carved into the frame and a corresponding ridge rendered along the edge of the screen for a perfect fit. Screen inserts come in a variety of sizes. Larger ones were placed inside and in front of the main door of buildings, while smaller ones could be placed on tabletops, being decorative objects to please the eye of the beholder. This jadeite screen insert is carved on one side with a mountain stream scene of pines and auspicious crane, alluding to the auspicious phrase, "Long life (like) pines and cranes". The other side is engraved with a pattern of waves and rocks, referring to another lucky term, "Mountains of fortune, seas of long life". Thus, this piece abounds with blessings for long life and good luck.

“White Jade Branch of Elegant Lychee, Agate Finger Citron” is actually in imitation of a kind of bitter gourd that grows in northern China. "Elegant lychee" is another name for "bitter gourd", also known as "leprous gourd", a form of the plant for decorative purposes. However, the terms "bitter" and "leprous" are not exactly positive in connotation, so the original brocaded case for this object in the Tung-nuan Pavilion of the Ch'ien-Qing Palace was provided with the title "White jade branch of elegant lychee", thus revealing the attention to and refinement in naming items by the court. The accompanying agate finger citron flower holder from the Museum collection seen here is also a decorative object overflowing with auspicious significance often seen in the Qing dynasty. It is carved into the shape of a finger citron (a kind of bergamot) with branch and leaves.

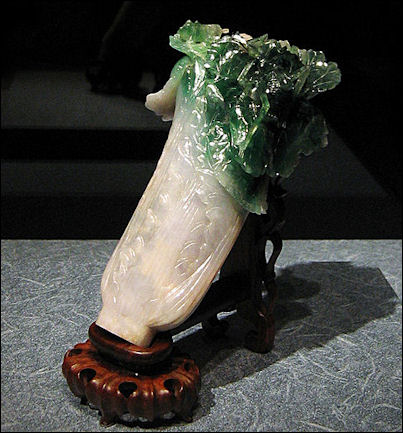

Jadeite Cabbage and the Meat-Shaped Stone

Qing period Jade cabbage

The famous "Meat-Shaped Stone of Qing dynasty (1644~1911) in the collections of the National Palace Museum, Taipei is a quartz curio of jasper chalcedony that looks just like stewed pork. Not only are the layers of fat and lean meat clearly defined, even the pores on the skin above are completely rendered. This piece and "Jadeite cabbage" are two of the Museum's most famous masterpieces that show how great craftsmanship not only enhance the beauty and features of natural objects, but it sometimes even outdoes them. The bands of layered textures formed by the infinity of Nature are further processed by the ingenuity of Human: tight tiny holes pose as pores and also serve to prime the grain for easier dyeing. The brownish red dye "marinates" the rind in soy sauce, adding a finishing touch in the transformation of a hard, cold stone into this piece of tender, juicy, melting-right-in-mouth Dongpo pork. What a humorous pact and collaborative act between Nature and Human, a wonderfully smart carving it is. The Meat-shaped Stone, on a metal stand is 5.3 centimeters long, 6.6 centimeters wide and 5.7 centimeters high

On its famous jadite cabbage, the National Palace Museum, Taipei says: “This jadeite, part green and part white, which is now a wonderful Chinese cabbage, would be considered mere second-rate material full of impurities if it was to be made into usual vases, jars, or ornaments, because of the cracks and blemishes that came with it. However, the artisan ingeniously transformed the rock into a lifelike vegetable of leafy green and white stems, with all unappealing rifts now hidden invisible amid the veins. And the discolored spots take on the marks of snow and frost. So with a stroke of genius, defects turn perfect. Beauty is in the detail and creativity works wonder. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“Jadeite is a type of jade found in the mountains stretching from Yunnan to Myanmar. It comes in ochre to brilliant green, echoing the colors of the kingfisher bird, hence the alternate name "kingfisher jade". This piece of jadeite carved into the form of a bokchoy cabbage was a decorative object in the Yung-ho Palace, but it was originally "planted" into a small enameled basin in the shape of a crab apple blossom with spirit fungi carved from red coral by its side. Rendered from a piece of half-grayish-white, half-green jadeite, the craftsmen cleverly used the original coloring of the mineral to carve it into a true-to-life stalk of bokchoy cabbage with leaves and veins clearly articulated. Also rendered at the top are a locust and its relative, a katydid. The katydid is commonly referred to as a "lady spinner". Due to its great propensity for procreation, in antiquity this insect family was considered an auspicious symbol for having many children and grandchildren. Even in the "Odes of Chou and South" from the ancient Book of Songs, it is written, "Oh, winged locusts collecting in such great numbers, how fitting is it that your descendants are so many."

“The cabbage used to be a curio item displayed in Eternal Harmony Palace, the residence quarter of Emperor Guangxu's Lady Jin. For this reason, the piece is thought to have belonged to her. Hence the inference that the "white" cabbage signifies purity or chastity of the bride, and the two insects alighting at the tips of leaves symbolize fertility: bringing a long line of imperial children to the royal family. The cabbage was previously "planted" in a cloisonné flowerpot as a potted landscape. The Jadeite Cabbage is 5.07 centimeters long, 9.1 centimeters wide, and 18.7 centimeters tall.

Stone Craft Pieces of the Qing Emperors

Agate Millstone: According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “A kind of revolving turntable-like tool made of stone used for grinding grain began to appear in the Qin and Han dynasties. Later generations would later call this a millstone. In general, a mill made of stone is composed of a round disc on top of a pedestal, the place where they meet being engraved with a saw-tooth pattern. The principle behind this mechanism is to pour grain through a hole in the center of the disc, which then enters the spaces between the teeth below. When the disc is turned in a circular motion, the grains are crushed repeatedly into a fine powder. The ancient Chinese believed that consuming certain minerals could enhance not only beauty but also divine insight. Consequently, in addition to grinding grain in millstones, they were also used for pulverizing minerals. Most mills were fashioned from stone, but this one made from a semi-precious form of the mineral quartz known as agate reveals the noble status of the imperial family member who used it. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

Gold Finial for a Court Crown Inlaid with Eastern Pearls: “Eastern pearls came from freshwater clams in the rivers of northeastern China. Since this area witnessed the rise of the ruling Manchu clan of the Qing dynasty, and the number of Eastern pearls was exceedingly rare, the Qing imperial clan considered the Eastern pearl as the most precious of gems. The imperial clan had a monopoly on these pearls; everybody else was forbidden from possessing or using them. In the official crown and clothing regulations of the Qing dynasty, all high-ranking officials had to wear a pearl-topped hat. However, according to a record in Statutes of the Great Qing, only the emperor, dowager empress, and empress could wear clothing decorated with the Eastern pearl. Symbolizing the supreme status of this pearl, no other people were allowed to use it. In addition to the pearl-topped hat in the Qing dynasty, some imperial crowns also were decorated with Eastern pearls — the greater the number, the higher the rank. This gold-strand finial for a court crown is topped by a single large pearl, with each of the lower three levels bearing an Eastern pearl. Each level is also decorated with four dragons and four Eastern pearls. The form and number of Eastern pearls seen here indicates that only someone of the highest rank could use this finial, meaning it was part of the imperial crown of the emperor himself.

Crystal Ball and the God of Longevity: Mineral crystal refers to the pure and colorless form of silica known as quartz. If there are needle-like inclusions of other minerals, such as rutile or tourmaline, it is called "hair crystal". In ancient China, this kind of mineral "pure as water and hard as jade" was also known by such names as "water jade", "water essence", and "Bodhisattva (pure) stone". The National Palace Museum, Taipei collection includes carvings from crystal and hair crystal, such as the "Crystal ball", that mysterious object of fascination in the West. In addition, a sculpture composed of a horse and monkey brings to mind the auspicious Chinese phrase "quickly ennobled". In this case, "quickly" means literally "on a horse" in Chinese, and "ennobled" is a homonym for "monkey", hence the reason why these two animals appear together. The display also includes a smiling figure with hands in reverence representing the God of Longevity offering long life, health, and peace.

Smoky Quartz Mirror: The mirror, an object of practical daily use, was often transformed in the past into beautifully crafted works of art. In Chinese antiquity, mirrors were usually made from such metals as bronze or iron, with those crafted from jade or stone being much rarer and all the more precious. This work was originally entitled "Black jade mirror", having once been considered carved from dark jade. In fact, the Guangxu Emperor once composed the poem "In Praise of a Black Jade Mirror", in which he wrote, "Stars sink to the bottom of the sea as the light of clouds turn black" and "Mirrored beard and hair appear pure and unadulterated". He was, in fact, perhaps referring to this mirror, even though modern scholars now believe it is not actually made from black jade, but "smoky quartz" instead.

Miniature Mountains of the Qing Dynasty

Lapis Lazuli Miniature Mountain

Jade-like stones and other beautiful minerals were also fashioned into works of art. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Qing dynasty emperors were quite cultivated and expressed great fondness for curios and objects of the scholar's studio. In order to meet the refined taste and demands of the imperial clan, craftsmen utilized many semi-precious materials, accommodating the unique forms and characteristics of such to create exquisite curios and studio objects. Tian Shan ("field yellow") stone is one of the most famous and valuable kinds of the mineral monazite from Shou-shan. Its texture and yellow color are said to be linked with the spirits, being lustrous and sparkling to the eye as well. A paperweight in made from the mineral in the form of a mystical beast is quite lifelike, for even its fine pores can be seen, making it extremely vivid. In carving the brush holder in smoky quartz, specks of white in the material were adapted into the pistils of plum blossoms. Circular forms were carved on the outside to indicate petals, imparting the animated engravings of plum blossoms an originality all their own.

Tian Shan Stone Miniature Mountain is a miniature mountain rendered from a large piece of Tian Shan stone, reflecting the grand manner of the Qing imperial family. Curling wisps of clouds were carved on this miniature mountain of Tian Shan. Engraved on the stone itself are two lines of poetry that read, "Celebratory clouds soar to the verdant sky, scenes of good fortune pervading the pure mist", thus fully echoing their noble Qing background. Tian Shan stone was favored among scholars and also also treasured by successive emperors of the Qing dynasty. In fact, there is a proverb that goes, "One or two pieces of Tian Shan equal one or two pieces of gold". Rare and precious Tian Shan stone was also greatly cherished and used for carving seals.

Lapis Lazuli Miniature Mountain is a miniature mountain was carved from a beautiful piece of indigo lapis lazuli. Engraved on it is a poem by the Qianlong Emperor and the title "Spirit-Transport.” The ancient Chinese name for lapis lazuli was "ch'iu-lin (beautiful stone)", and it was also known as "blue gold", "essence of gold", and "gold star" stone. Lapis lazuli, with its azure sky-blue color, sometimes contains scatterings of pyrite ("fool's gold"), producing the effect of a starry sky in early evening. Consequently, in ancient times, it was often considered a mineral of mysterious colors.

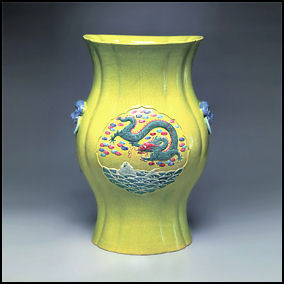

Qing Porcelain

Qing dynasty porcelain was famous for its polychrome decorations, delicately painted landscapes, and bird and flower and multicolored enamel designs. Many of the subjects had symbolic meanings. The work of craftsmen reached a high point during the reign of Emperor Kangxi (1662-1722).

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “ In 1680 the famous kilns in the province of Jiangxi were reopened, and porcelain that is among the most artistically perfect in the world was fired in them. Among the new colours were especially green shades (one group is known as famille verte) and also black and yellow compositions. Monochrome porcelain also developed further, including very fine dark blue, brilliant red (called "ox-blood"), and white. In the eighteenth century, however, there began an unmistakable decline, which has continued to this day, although there are still a few craftsmen and a few kilns that produce outstanding work (usually attempts to imitate old models), often in small factories.

According to the Yomiuri Shimbun: Ceramics created during the Qing dynasty (1636-1912) are outstanding thanks to their vibrant colours. Some of the best pieces feature an overglaze polychrome enamel. Patterns are impressively accentuated with the funsai technique, which features pink pigment and delicate gradations. It is surprising to see that their original vivid colours remain even after several hundred years. The highest quality pieces were manufactured in a kiln used for firing items bound exclusively for emperors and their courtiers. Works made during the reign of Emperor Qianlong (ruled 1735-1795) feature elaborate and gorgeous patterns. [Source: Yomiuri Shimbun, Asia News Network, November 4, 2013]

Qing Dynasty’s Government-Run Porcelain Kilns

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “In the early period of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), during the reigns of Kangxi (1662-1722), Yongzheng (1722-1736), and Qianlong (1736-1795), the court considered the appointment of the supervising official at the imperial porcelain factory at Jingdezhen a serious matter. This represented a reform from the Ming practice of entrusting control to court eunuchs, and as a result there appeared great progress in craftsmanship at the factory, picking up the legacy of Ming dynasty skill and taking it to the pinnacle of its development. The use of brilliant, glittering fen-ts'ai enamels is a characteristic of porcelain in the Qing dynasty. During a rebellion in 1853, the imperial factory was burned. Rebels sacked the town and killed some potters. The factory was rebuilt in 1864 but never regained its former stature. With the end of the Qing dynasty in 1912, the long history of Chinese porcelain making drew to a close. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

The production of Qing imperial wares was controlled by the imperial family. Due to better kiln administration and worker pay, imperial wares were able to continuously maintain supremacy at this time in terms of quantity and quality. During the High Qing period, the emperors Kangxi, Yongzheng and Qianlong were personally involved in the process of production while superintendents under their command closely oversaw the management of imperial kilns. As a result, the techniques, glazes, forms and patterns of official wares were unparalleled. Qing imperial wares of the time possess an imposing manner possessing both antiquarian elements and innovative styles that reflect the effort of the Manchu rulers trying to fit into the tradition of Han Chinese culture. Qing imperial wares also often represent a mix of contemporary Western and Eastern decorative styles.

“In the late Qianlong period, the management of imperial kilns was entrusted to local supervising authorities. Imperial models of style became less influential over time as elements of popular taste among common folk increased. Although imperial wares in the Jiaqing and Daoquang reigns inherited the High Qing style, they were no longer as vivid, vigorous and creative as their predecessors. Starting from the Xianfeng reign, chaos appeared throughout the empire. The imperial kilns at Jingdezhen were destroyed and ceased functioning. After the Taiping Rebellion during the Tongzhi reign, the imperial kilns were again revived. Empress Dowager Cixi, who exercised control of the government at the time, actively oversaw the production of her personal wares and preferred bright colors. In the late Guangxu period, the operation of imperial kilns was entrusted to civilians, and the so-called “official ware” came to an end when the Xuantong Emperor abdicated the throne at the fall of the Qing dynasty.

Yang-Tsai: Porcelain with Western Influences

porcelain cicada

Yang-tsai was a kind of porcelain with Western influenced that very popular with the Qianlong Emperor (ruled 1735-1795. According to Tang Ying, supervisor of the imperial kilns, they are "porcelains on which a new technique borrowed from Western painting method is used." He also said that they were "white ceramics with paintings in wu-ts'ai colors, using Western techniques, hence the name." They were porcelains with outstanding paintings of figures, landscapes, flowers and plumage, using painting techniques from the West. The Archives of the Imperial Workshops of the time classify them as "fa-lang enamel ceramics in the Ch'ien-Qing-kung Palace," and the Qing Court Inventories list both Yang-tsai and fa-lang-ts'ai porcelains as "ceramics bearing Qianlong's seals." Clearly, then, the two types were closely associated with each other. Yang-tsai porcelains are classed as fa-lang-ts'ai enamel wares, and are painted porcelains employing Western painting techniques and décor. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The vast majority of Yang-tsai porcelains and painted fa-lang-ts'ai porcelains kept in the Ch'ien-Qing-kung Palace were made in pairs. However, whereas both pieces in the Yang-tsai pairs were virtually identical in their shape, decoration, composition and the details, the fa-lang-ts'ai pairs had slight differences in decoration. This is one of the ways in which the two types of porcelain can be distinguished from each other. For details, see the table "Classification of Yang-tsai and Painted Fa-lang-ts'ai Porcelains".

From Qing historical archives and actual examples we can identify the following criteria which qualify a piece of porcelain as Yang-tsai: 1) The use of Western shading techniques, especially in the rendering of the décor on the porcelains to give the body a three-dimensional quality. 2) The use of white pigment on many of the leaf patterns on the flower illustrations, to represent light and shadow (a painting technique rarely seen on the painted fa-lang-ts'ai porcelains). 3) The reliance on Western shading and perspective painting techniques on figurative compositions. 4) The use of Western-style flowers, such as the chrysanthemum and anemone, and the liberal use of Western floral compositions for a number of decorative patterns.

Falangcai, Yangcai and Fencai Painted Enamel Porcelains

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ “Falangcai, Yangcai and Fencai are the three major terms used for Chinese porcelain painted with enamel. Falangcai porcelain is decorated with enamel pigments and combine Chinese and Western painting techniques, and was manufactured in the Qing court's Imperial Workshops. Yangcai porcelain was manufactured in the imperial kilns at Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province, and was sometimes decorated with enamel pigments. Fencai was a new term for Yangcai porcelain in the late Qing and early Republic of China periods. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

“As opposed to general overglaze painted porcelains, falangcai porcelains fired in the Kangxi reign use enamel pigments painted on metal vessels. The pulverized glass powder needed to be mixed with glue or oil to make it stick to the vessel surface. In the beginning, the limited availability of imported pigments meant that production had to rely on a mixture to create different enamel colors. The concept of Western gold-red enamel using gold as colorant had been unheard of before the Qing dynasty, stirring great interest at the Yongzheng and Qianlong courts, which strived to develop it on their own. These rose enamel works using gold as colorant reflect the experimentation conducted by the Kangxi and Yongzheng courts and the process of their grasping related techniques.

“During the process of firing and production of porcelain with painted enamels, the steps of painted patterns and the marking were almost completed in the Imperial Workshops. The category "Made in the reign of Yongzheng" reign mark in blue enamel at the bottom of the pieces belongs to the enameled mark from Qing court, and they stand for being painted and re-fired in the Imperial Workshops.

“Both Emperor Kangxi and Yongzheng paid much attention to the porcelain with painted enamels. As a result, the style of the Jingdezhen productions had been very similar to the falangcai porcelains since the reign of Kangxi, but under the pieces have their own four-character marks in underglaze blue. The productions fired in the reign of Kangxi have "Imperial production of Kangxi" written under the piece, and the productions fired in the reign of Yongzheng have "Imperial production of Yongzheng" written under the piece. On the one hand, it's an implication of inheritance from Kangxi to Yongzheng. On the other hand, it is also a lable that they were made in the imperial kilns of Jingdezhen.

“In terms of falangcai decoration, it includes the four elements of poetry, calligraphy, painting, and seals. Since these are rarely seen on vessels made outside of the court, they may thus be inferred as belonging to the "court-style type." In tracing its origins, a connection can be made with the twelve floral deity cups of the Kangxi reign, but the decoration of Yongzheng falangcai porcelains is even richer and more varied in terms of painting, poetry, and seals. Not only at once were the formalistic compositions of the twelve floral deity cups changed, but close cooperation between painting and calligraphy craftsmen allowed the contents of the poetry, painting, and seals to be integrated, thereby highlighting the virtues of each.

Qing Era Porcelain Exports

The primary Ming-era export item to Europe and other places in the world was porcelain. From the beginning production at the Ming porcelain factories in Jingdezhen were oriented towards the export market. The factories produced coffee cups and beer mugs centuries before these drinks became popular in China. They also produced plates with Arabic and Persian motifs and place setting emblazoned with European coats of arms.

The primary Ming-era export item to Europe and other places in the world was porcelain. From the beginning production at the Ming porcelain factories in Jingdezhen were oriented towards the export market. The factories produced coffee cups and beer mugs centuries before these drinks became popular in China. They also produced plates with Arabic and Persian motifs and place setting emblazoned with European coats of arms.

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “One of the most important Chinese exports to Europe in the 17th century was porcelain, which had been invented in China about 1,000 years earlier. As European demand for Chinese porcelain grew (in part because European ceramic centers at this time did not possess the technical knowledge required to manufacture porcelain), porcelain from China, and later Japan, was by the 1630s flooding the Europe market. The Dutch alone were importing more than one million pieces per year. But in the 1680s, the Kangxi Emperor reasserted imperial control over the kilns at Jingdezhen in Jiangxi (an area renowned for having the finest clay and for producing porcelain fit for an emperor), and the export of Chinese porcelain to Europe came to a halt for a period of time. This interruption in supply led in part to renewed attempts at ceramic centers across Europe to unlock the "secret" to Chinese porcelain, which did happen eventually but not until early in the 18th century. Prior to this time Europeans could only copy the look of Chinese porcelain models and keep working to duplicate the translucent quality of Chinese porcelain. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Maxwell K. Hearn, Consultant learn.columbia.edu/nanxuntu]

“Today the term "Made in China" has gained a somewhat negative connotation as something that's an inexpensive imitation of "the real thing." Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, however, the situation was quite the other way around when it came to porcelain. The European ceramics centers were far less sophisticated in their manufacturing techniques, and Chinese decorative arts had a huge influence on European tastes during this time.

Profitable Porcelain Production and Efforts by Europeans to Learn Its Secret

The porcelain trade was so lucrative that the porcelain making processes were closely guarded secrets and Jingdezhen was officially off limits to visitors to keep spies from uncovering these secrets. Over three million pieces were exported to Europe between 1604 and 1657 alone. This was around that the same time that the word "china" began being used in England to describe porcelains because the two were so closely associated with each other.

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Porcelain Production in China: The manufacture of porcelain in China evolved over time into a highly specialized set of related crafts that together formed an entire industry. There were those who specialized in mining kaolin clay, others whose specialty was to mix the raw clay with other materials to create the particular mixture used for porcelain, and still others who actually shaped the objects, others who fired them, and still others whose specialty it was to paint and decorate the final pieces. As demand continued to increase, porcelain production in China began to resemble a highly specialized, mass-production-style industry. A common view of the industrial revolution as it occurred in England in the 1750s is that the burgeoning textile industry was a key contributor to the complex interaction of various socioeconomic developments that led to that phenomenon; mentioned less often is the possibility that the porcelain industry, as it evolved in China, may have also contributed to this development. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Maxwell K. Hearn, Consultant learn.columbia.edu/nanxuntu]

Pere d’Entrecolles, a Jesuit missionary from France, secretly entered Jingdezhen and described porcelain making in the city in letters that made their way to Europe in the early 1700s. He described a city with a million people and 3,000 kilns that were fired up day and night and filled the night sky with an orange glow. He learned the process but confused the clays. Around he same time that d’Entrecolles was describing porcelain-making in Jingdezhen, Germans working independently in their homeland discovered the secret to making porcelain Large scale porcelain production began in the West in 1710 in Meissen, Germany. Chinese porcelain dominated the world until European manufacturers such as those in Messen, Germany and Wedgewood, England began producing products of equal quality but at a cheaper price. After that the Chinese porcelain industry collapsed as many industries have done today when underpriced by cheap Chinese imports.

Qing Dynasty Vase Sells for a World Record $41.6 Million

In 2021, a Qing Dynasty (1644-1912) vase sold for $41.6 million, a world record for Chinese ceramics. Antiques and the Arts Weekly reported: The world record for a Chinese ceramic has been reset at $41.6 million, which Poly Auctions realized on June 7. The intricate four-piece Imperial yangcai ruby ground with carved openwork “phoenix scene” revolving vase, was made during the Qianlong period (1736-1795). [Source: Antiques and the Arts Weekely, World June 22, 2021

The form features an outer shell as well as an interior vase, neck and cover, all parts requiring each element to be separately glazed, enameled and fired perfectly. Few revolving vases survive and, standing 24¾ inches tall, the example sold by Poly is only the second tallest known to survive.

The vase was not fresh to the market; it had crossed the block at Christie’s London in 1999 when it sold to Chinese art dealer William Chak, for $537,030. It subsequently sold to an Asian collector, who was the one selling it through Poly Auctions. The previous world record for Chinese ceramic was $37.7 million, which was achieved for a Northern Song dynasty (907-1127) Ru Guanyao brush washer by Sotheby’s Hong Kong in April, 2017. In 2010, $32.4 million was paid for a Qing double-gourd vase.

Image Sources: Palace Museum, Taipei Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021