MODERN HUMANS IN CHINA

one rendering of Stone-Age modern humanThe earliest evidence of modern humans in China — dated to 80,000–120,000 years before present — was found at Fuyan Cave in southern China's Hunan province. At Fuyan Cave Teeth were found under rock over which 80,000 years old stalagmites had grown. Genetic studies of 28 of China's 56 ethnic groups, published by the Chinese Human Genome Diversity Project in 2000, indicate that the first Chinese descended from Africans who migrated along the Indian Ocean and made their way to China via Southeast Asia. [Source: Wikipedia]

In December 2007, an almost complete human skull estimated to be 100,000 years old was found in Xuchang in the central province of Henan. The fossil consists of 16 pieces of skull with protruding eyebrows and a small forehead. Li Zhanyang, an archeologist with the Henan Cultural Relics and Archeology Research Institute told Reuters, “More astonishing than the completeness of the skull is that it still has a fossilized membrane on the inner side, so scientist can track the nerves of the Paleolithic ancestor." The fossil was discovered after two years of excavations. Li said, “We expect more discoveries of importance."

According to Archaeology magazine: Obscure engravings on animal bones from the site of Lingjing in Henan Province suggest that early hominins who lived there 125,000 years ago may have had more advanced cognitive abilities than once believed. The mysterious markings proved to have been etched into the bone, which was then rubbed with red ochre powder to make the markings more visible. Experts do not yet know why early humans made these abstract designs, nor what they represent. [Source: Archaeology magazine, November-December 2019]

According to Archaeology magazine: A skull fragment more than 100,000 years old displays the signs of a rare congenital birth defect called an enlarged parietal foramen. The bones, excavated in northern China in the 1970s, suggest that the individual also had neurological deficiencies. Combined with other rare genetic conditions that have been observed in early human fossils from this period, the researchers theorize that inbreeding, which can result in a greater incidence of such defects, may have been used as a survival strategy for certain isolated small populations. [Source: Samir S. Patel, Archaeology magazine, July-August 2013]

Evidence of human habitation has been found on Minatogawa, an island between Taiwan and Japan, dated to 18,000 years ago, and at Zhoukoudian (Shadingdong) in central-eastern China, dated to 11,000 years ago. Pottery vessels, weapons, and stone tools have been discovered in Chinese graves dating back to Neolithic times (9000-6000 B.C.).

See Separate Article:EARLIEST HOMININS AND HUMAN ANCESTORS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HOMO ERECTUS IN CHINA: SITES, FOSSILS, IMPLICATIONS factsanddetails.com ; PEKING MAN: ZHOUKOUDIAN, FIRE, DISCOVERY AND DISAPPEARANCE factsanddetails.com ; UNUSUAL HUMAN-LIKE FOSSILS FROM CHINA FROM 300,000 TO 100,000 YEARS AGO factsanddetails.com ; GENETIC ORIGIN OF THE CHINESE AND THEIR LINKS TO TIBETANS, TURKS, MONGOLS AND AFRICANS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:“Emergence and Diversity of Modern Human Behavior in Paleolithic Asia” by Yousuke Kaifu, Masami Izuho, et al. Amazon.com; “Asian Paleoanthropology: From Africa to China and Beyond” (Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology) by Christopher J. Norton and David R. Braun Amazon.com; “Paleoanthropology and Paleolithic Archaeology in the People's Republic of China” by Wu Rukang, John W Olsen Amazon.com; “Peking Man” Amazon.com; “Liangzhu Culture” by Bin Liu, Ling Qin, et al. Amazon.com; “A Brief History of Ancient China” by Edward L Shaughnessy Amazon.com

Fuyan Cave: Evidence of Modern Humans in China At Least 80,000 Years Ago

Modern human skull (but not from China) In 2015, Chinese scientists announced they discovered 47 teeth from modern humans in Fuyan Cave in southern China's Hunan province that date back at least 80,000 years. Zach Zorich wrote in Archaeology magazine: Fuyan Cave does not contain any artifacts, but it did have 47 teeth that came from the mouths of Homo sapiens The teeth came from at least 13 individuals. There is no evidence that people ever lived in the cave, and Martinon-Torres suspects the teeth were washed in by a flood. The 47 teeth all have characteristics of Homo sapiens dentition: They are relatively small and lack the complex convolutions on the chewing surfaces of other hominin teeth. They were found among the bones and teeth of other Pleistocene mammals, including hyena, giant tapir, an extinct species of elephant, and a possible ancestor of the panda. Martinon-Torres hopes that genetic analysis and further archaeological investigation will reveal how the people of Fuyan Cave are related to modern-day people. [Source:Zach Zorich, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2016]

Charles Q. Choi wrote in Live Science: China “is dotted with fossil-rich caves. Fuyan Cave is part of a system of caves more than 32,300 square feet (3,000 square meters) in size. Excavations from 2011 to 2013 yielded a trove of 47 human teeth, as well as bones from many other extinct and living animals, such as pandas, hyenas and pigs. The scientists detailed their findings in the Oct. 15 issue of the journal Nature. [Source: Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, October 14, 2015 ~~]

“The researchers found these teeth are more than 80,000 years old, and may date back as far as 120,000 years. Until now, fossils from southern China confirmed as older than 45,000 years in age that can be confidently identified as modern human in origin have been lacking. "Our discovery, together with other research findings, suggests southern China should be the key, central area for the emergence and evolution of modern humans in East Asia," the study's co-lead author, Wu Liu, of China's Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing, told Live Science. ~~

Does Fuyan Cave Show Early Humans Reached China Before Europe?

▪ The Fuyan Cave find shows that modern man had reached China more than 30,000 years before entering Europe, and is changing ideas about how Homo sapiens settled the world beyond Africa. Charles Q. Choi wrote in Live Science, “Teeth from a cave in China suggest that modern humans lived in Asia much earlier than previously thought, and tens of thousands of years before they reached Europe, researchers say...Modern humans first originated about 200,000 years ago in Africa. When and how the modern human lineage dispersed from Africa has long been controversial. Previous research suggested the exodus from Africa began between 70,000 and 40,000 years ago. However, recent research hinted that modern humans might have begun their march across the globe as early as 130,000 years ago. [Source: Charles Q. Choi, Live Science, October 14, 2015 ~~]

“These newfound teeth are smaller than counterparts of similar ages from Africa and elsewhere in China. Instead, they more closely resemble teeth from contemporary modern humans. This suggests different kinds of humans were living in China at the same time — archaic kinds in northern China, and ones more like modern humans in southern China.The researchers said these findings could shed light on why modern humans made a relatively late entry into Europe. There is currently no evidence that modern humans entered Europe before 45,000 years ago, even though they made it as far as southern China at least as early as 80,000 years ago. The investigators suggested that Neanderthals might have prevented modern humans from crossing into Europe until after Neanderthals began dying off.” The main thing holding scientists back from making further conclusions is that archaeological evidence is lacking from Fuyan Cave and other sites from that period in China." ~~

Maria Martinon-Torres, a paleoanthropologist at University College London, told Archaeology magazine Neanderthals and other archaic hominins such as the Denisovans may have kept Homo sapiens out of Europe and northern Asia for at least 40,000 years. Homo sapiens then could have moved into those areas after the populations of Neanderthals and Denisovans began to collapse. “We should leave behind the idea of hominins dispersing as if they were tourists or a troop Marching, in a lineal fashion,” says Martinon-Torres. Instead of settling lands closest to Africa first, our species might have traveled the unoccupied coast of South Asia into what is now China. [Source: Zach Zorich, Archaeology magazine, January-February 2016]

100,000-Year-Old Modern Human Fossil Found in Guanxi, China

A 100,000- year-old fossil human jawbone discovered in southern China has raised serious questions about when the modern humans migrated out of Africa. The mandible, unearthed by paleontologists in Zhiren Cave in Guanxi Province in southern China in 2007, sports a distinctly modern feature: a prominent chin. The fossil was called "the oldest modern human outside of Africa," by study co-author Erik Trinkaus, an anthropologist at Washington University in St. Louis. [Source: Rachel Kaufman, National Geographic News, October 25, 2010 |~|]

The discovery of such an ancient example of a modern human in China drastically alters the time line of human migration. The find may also mean that modern humans in China were mingling---and possibly even interbreeding---with other human species for 50,000 or 60,000 years. |~|

The find also seems to suggest that anatomically modern humans had arrived in China long before the species began acting human. For example, symbolic thought is a distinctly human trait that involves using things such as beads and drawings to represent objects, people, and events. The first strong evidence for this trait doesn't appear in the archaeological record in China until 30,000 years ago, Trinkaus said. |~|

So far, genetic evidence largely supports the traditional timing of the "out of Africa" theory. But the newly described China jawbone presents a strong challenge, said anthropologist Christopher Bae of the University of Hawaii, who was not associated with the find. "They actually have solid dates and evidence of, basically, a modern human," he said. |~|

Still, the jaw and three molars were the only human remains retrieved from the Chinese cave, and the jaw is "within the range" of Neanderthal chins as well as those of modern humans, added paleoanthropologist John Hawks of the University of Wisconsin, Madison. "If this holds up, we have to reevaluate" the human migration time line, he said. "Basically, I think they're right, [but] I want to see more evidence," Hawks added. "I really, really hope that there can be some sort of genetic extraction from this [fossil]." The oldest human jawbone from China is described in an October 2010 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. |~|

Tianyuan Man — 40,000-Year-Old Modern Human Fossil in China

In 2007, researchers announced they had found 34 bone fragments belonging to a single individual at the Tianyuan Cave site in the Zhoukoudian region, near where the Peking Man bones were found and not far from Beijing. The bones were first discovered in 2003. Based on radiocarbon analysis, the bones were dated to be 42,000 to 38,500 years old, making it about the same age as an early modern humans from Romania, and a skeleton from a Niah Cave in Sarawak, Malaysia. The individual who the bones belonged to was given the name Tianyuan Man. [Source: John Roach, National Geographic News, April 3, 2007 ^]

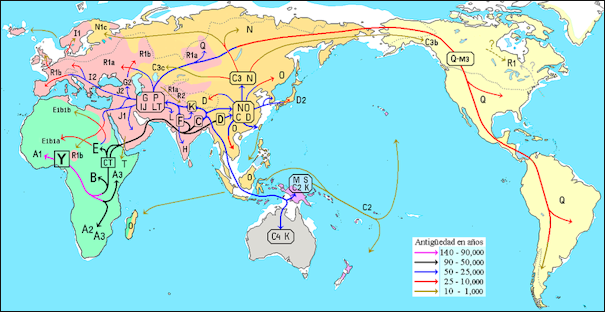

Human migrations based on genetic evidence beginning 140,000 years ago

John Roach wrote in National Geographic News: “The find adds to evidence that the first Homo sapiens occasionally mated with older human species such as Neanderthals. The remains share a few characteristics with older human species, according to a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science by Erik Trinkaus, an anthropologist at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, and colleagues with the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. ^

“The Chinese skeleton and similarly dated specimens from Europe and Asia have traits that had already been lost in the earliest modern humans found in Africa. You would think the 40,000-year-old modern human skeletons from outside Africa should look modern human fossils from Africa or slightly more evolved. "What we find is overwhelmingly they do," Trinkhaus said. "But these archaic characteristics that had been lost in African moderns keep popping up." ^

“The skeleton from China, for example, has a genetically determined dental feature common in Neanderthals that is not present in early modern humans from Africa. "When we look at this new Chinese specimen, what we see is the archaic in tooth proportions. The individual has relatively large, big front teeth," Trinkhaus said. The China specimen also has the spatula-shaped, rounded fingertips common among older human ancestors, instead of the narrow fingertips of early modern humans from Africa. The wristbones, as well, display archaic features, Trinkaus said. "So it's a couple of little features like this that show up in this individual. And so yes, it's a modern human, but given the earlier African modern humans, it's not just what you would expect," he said. ^

Chris Stringer, the head of the human-origins program at the Natural History Museum in London, England, said the Chinese skeleton is an important find that will help document the process of how modern humans became established in the region. However, he is unconvinced that the skeletal analysis is proof of interbreeding between early modern humans from Africa and more archaic species. "The problem is that we lack decent samples of early modern humans from Africa between [40,000 and] 80,000 years ago," he commented in an email. But the appropriate skeletal evidence is not yet represented in the fossil record, he said. "I will keep an open mind on the extent of hypothesized admixture, while noting the interesting fact that this skeleton shows the same linear physique as early European and Israeli early moderns---a physique that may reflect a recent African origin," he said. Stringer said, "There are just a couple of data points there, but it's very hard for me to explain the anatomy we see in both [the Malaysian and Chinese] specimens without saying, Yes indeed, people do what people do: that is, they get it together," he said. And sometimes when it comes to selecting mates, he added, "people are not very choosy."” ^

Isotope analysis of Tianyuan Man suggests that a substantial part his diet came from freshwater fish (See Below). DNA-testing of haplogroup B in 2013 revealed that he was related "to many present-day Asians and Native Americans...but had already diverged genetically from the ancestors of present-day Europeans". [Source: Wikipedia]

Modern Human Sites in China

Zhoukoudian

In 1973, the so-called 'New Cave Man' was discovered at Zhoukoudian, where hominin remains dating to 200,000 to 100,000 years ago were found. Around 20,000 years ago, the humans living in the vicinity of Zhoukoudian were given the name Mountaintop Cave Man following the discovery of their remains in a cave above the Beijing Man Cave. Discovered in 1933, the cave contained some interesting artifacts, including an 82-millimeter bone needle, with a shiny surface, slightly arced in shape, and very sharp side. A very fine instrument was sued to hollow out a tiny hole. It is believed that Mountaintop Cave Man sewed and clothed himself with animal hides and leather. Among the other objects found at the site have been earrings, animal teeth with holes in them for stringing, fishbones, ocean shells, stone beads, and bones carved in particular ways. [Source: China’s Museums]

In July 2015, Archeology magazine reported; The 100,000-year-old remains of at least nine individuals have so far been unearthed at the Lingjing Historical Site in central China by a team from the Henan Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology. Two of the limb bones, which may have belonged to the same young individual, carry bite marks. “We are not quite sure whether those [bite marks] were from predators or other humans,” researcher Li Zhanyang told China Daily. Sixteen pieces of a skull known as Xuchang Man that still bore traces of a fossilized membrane were recovered from the site in 2008. “Different from the ancient human skull fossils that were discovered eight years ago, the first discovery of limb bone fossils provides more opportunities to decode the process of human evolution,” Li said. [Source: Archeology magazine Thursday, July 23, 2015]

Peking Man Site: Home of Early Modern Human As well as Homo erectus

Zhoukoudian was declared a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage Site in 1987. According to UNESCO: The 480-hectare “Peking Man Site at Zhoukoudian is a Pleistocene hominin site on the North China Plain. This site lies... at the juncture of the North China Plain and the Yanshan Mountains. Adequate water supplies and natural limestone caves in this area provided an optimal survival environment for early humans. Scientific work at the site is still under way. So far, ancient human fossils, cultural remains and animal fossils from 23 localities within the property dating from 5 million years ago to 10,000 years ago have been discovered by scientists. These include the remains of Homo erectus pekinensis, who lived in the Middle Pleistocene (700,000 to 200,000 years ago), archaic Homo sapiens of about 200,000–100,000 years ago and Homo sapiens sapiens dating back to 30,000 years ago. At the same time, fossils of hundreds of animal species, over 100,000 pieces of stone tools and evidence (including hearths, ash deposits and burnt bones) of Peking Man using fire have been discovered. [Source: UNESCO ~]

“As the site of significant hominin remains discovered in the Asian continent demonstrating an evolutionary cultural sequence, Zhoukoudian is of major importance within the worldwide context. It is not only an exceptional reminder of the prehistoric human societies of the Asian continent, but also illustrates the process of human evolution, and is of significant value in the research and reconstruction of early human history. ~

“The discovery of hominin remains at Zhoukoudian and subsequent research in the 1920s and ‘30s excited universal interest, overthrowing the chronology of Man’s history that had been generally accepted up to that time. The excavations and scientific work at the Zhoukoudian site are thus of significant value in the history of world archaeology, and have played an important role in the world history of science.”

40,000 Year-Old Tianyuan Man Was a Regular Fish Eater

Analyses of collagen extracted from the lower mandible of the 40,000-year-old human skeleton found in the Tianyuan Cave near Beijing showed the individual that possessed the mandible was a regular consumer of fish. The Max Planck Society reported: “The isotopic analysis of a bone from one of the earliest modern humans in Asia, the 40,000 year old skeleton from Tianyuan Cave in the Zhoukoudian by an international team of researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, the Graduate University of Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing, the University of British Columbia in Vancouver and Washington University in Saint Louis has shown that this individual was a regular fish consumer [Source: Max Planck Society, July 7, 2009; Original work: “Stable Isotope Dietary Analysis of the Tianyuan 1 Early Modern Human” by

Yaowu Hu, Hong Shang, Haowen Tong, Olaf Nehlich, Wu Liu, Chaohong Zhao, Jincheng Yu, Changsui Wang, Erik Trinkaus, Michael P. Richards, PNAS. July 7, 2009. Vol. 106, No. 27 /]

“Freshwater fish are a major part of the diet of many peoples around the world, but it has been unclear when fish became a significant part of the year-round diet for early humans. Chemical analysis of the protein collagen, using ratios of the isotopes of nitrogen and sulphur in particular, can show whether such fish consumption was an occasional treat or part of the staple diet. /

“The isotopic analysis of the diet of one of the earliest modern humans in Asia, the 40,000 year old skeleton from Tianyuan Cave near Beijing, has shown that at least this individual was a regular fish consumer. Michael Richards of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology explains “Carbon and nitrogen isotope analysis of the human and associated faunal remains indicate a diet high in animal protein, and the high nitrogen isotope values suggest the consumption of freshwater fish.” To confirm this inference the researchers measured the sulphur isotope values of terrestrial and freshwater animals around the Zhoukoudian area and of the Tianyuan human. /

“Since fish appeared on the menu of modern humans before consistent evidence for effective fishing gear appeared, fishing at this level must have involved considerable effort. This shift to more fish in the diet likely reflects greater pressure from an expanding population at the time of modern human emergence across Eurasia. “This analysis provides the first direct evidence for the consumption of aquatic resources by early modern humans in China and has implications for early modern human subsistence and demography”, says Richards.” /

Unusual 11,500-Year-old Humans Found in Guanxi

Jill Neimark wrote in Discover: “Remains unearthed in 1979 in a cave in China’s Guangxi Province may belong to a previously unknown, anatomically unique modern human species. Neglected until a team of Australian and Chinese scientists decided to take a closer look, the remains are between 11,500 and 14,500 years old, says Darren Curnoe, a paleoanthropologist at the University of New South Wales who interpreted the find. Curnoe nicknamed the bones the Red Deer Cave people; he and his colleagues compared them with modern and contemporary human remains from Asia, Australia, Europe, and Africa, as well as with Pleistocene East Asian hunter-gatherer skulls. The Pleistocene age lasted from about 2,588,000 to 11,700 years ago. [Source: Jill Neimark, Discover, December 17, 2013]

“The Red Deer specimens have an unusual short, flat face, prominent browridges, and no human chin,” Curnoe says. They could be related to very early Homo sapiens that evolved in Africa and then migrated out to Asia. Or, as Curnoe believes, they might represent a new human species that evolved in parallel with Homo sapiens. If he is correct, we shared the planet with other human species right up to the dawn of agriculture.

“Some experts, however, reject both explanations. “These specimens should have been compared to early Holocene skeletons from China,” because they look much the same, contends paleoanthropologist Peter Brown, from the University of New England in Australia. The Holocene era began just as the Pleistocene era ended. Curnoe counters, however, that the key comparison is with Pleistocene East Asian skulls and recent hunter-gatherer and agricultural populations.”

fossils from Zhiren Cave

Paleolithic China

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “After the period of the Peking Man there comes a great gap in our knowledge. All that we know indicates that at the time of the Peking Man there must have been a warmer and especially a damper climate in North China and Inner Mongolia than today. Great areas of the Ordos region, now dry steppe, were traversed in that epoch by small rivers and lakes beside which men could live. There were elephants, rhinoceroses, extinct species of stag and bull, even tapirs and other wild animals. [Source: A History of China by Wolfram Eberhard (1909-1989), University of California, Berkeley, Project Gutenberg Ebook gutenberg.org]

“About 50,000 B.C. there lived by these lakes a hunting people whose stone implements (and a few of bone) have been found in many places. The implements are comparable in type with the palaeolithic implements of Europe (Mousterian type, and more rarely Aurignacian or even Magdalenian). They are not, however, exactly like the European implements, but have a character of their own. We do not yet know what the men of these communities looked like, because as yet no indisputable human remains have been found. All the stone implements have been found on the surface, where they have been brought to light by the wind as it swept away the loess. These stone-age communities seem to have lasted a considerable time and to have been spread not only over North China but over Mongolia and Manchuria.

“It must not be assumed that the stone age came to an end at the same time everywhere. Historical accounts have recorded, for instance, that stone implements were still in use in Manchuria and eastern Mongolia at a time when metal was known and used in western Mongolia and northern China. Our knowledge about the palaeolithic period of Central and South China is still extremely limited; we have to wait for more excavations before anything can be said. Certainly, many implements in this area were made of wood or more probably bamboo, such as we still find among the non-Chinese tribes of the south-west and of South-East Asia. Such implements, naturally, could not last until today.

“About 25,000 B.C. there appears in North China a new human type, found in upper layers in the same caves that sheltered Peking Man. This type is beyond doubt not Mongoloid, and may have been allied to the Ainu, a non-Mongol race still living in northern Japan. These, too, were a palaeolithic people, though some of their implements show technical advance. Later they disappear, probably because they were absorbed into various populations of central and northern Asia. Remains of them have been found in badly explored graves in northern Korea."

Polished Stone Tools in China

The earliest polished stone tools in China, dated to 24,000-22,000 years ago, were found at the Bailiandong site in southern China. They include axes, adzes, cutters with polished blades. But these only had polished blades. Fully polished stone tools would appear only thousands of years later (Source: “Early polished stone tools in South China evidence of transition from Palaeolithic to Neolithic“, “UDK 903(510)633/634?Documenta Praehistorica XXXI).

Stone tools of Southern China have been broken down into three stages of development: 1) blade polished only; 2) entire tool finely ground with blade polished; 3) entirely polished. The oldest polished tools in the world were discovered in Japan. See Japan, History.

To read more about the transition from the Paleolithic to Neolithic Bailiandong culture in Southern China, see “C AMS dating the transition from the Paleolithic to the Neolithic of Southern China,” by SixunYuan et al. According to a report, inhabitants of the Xiaohexi site, in Inner Mongolia, the earliest prehistoric settlement in the northeast, knew how to make polished stone tools 8,500 years ago.[Source: Aileen Kawagoe, Heritage of Japan website, heritageofjapan.wordpress.com]

biface ax

Microblades Linked with Mobile Adaptations in North-Central China

In 2013, Phys.org reported: “Though present before the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, around 24,500–18,300 years ago), microblade technology is uncommon in the lithic assemblages of north-central China until the onset of the Younger Dryas (YD, around 12,900–11,600 years ago). Dr. GAO Xing, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology (IVPP), Chinese Academy of Sciences, and his team discussed the origins, antiquity, and function of microblade technology by reviewing the archaeology of three sites with YD microlithic components, Pigeon Mountain (QG3) and Shuidonggou Locality 12 (SDG12) in Ningxia Autonomous Region, and Dadiwan in Gansu Providence, suggesting the rise of microblade technology during Younger Dryas in the north-central China was connected with mobile adaptations organized around hunting, unlike the previous assumption that they served primarily in hunting weaponry. Researchers reported online in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. [Source: Phys.org, June 13, 2013 ==]

“The late Pleistocene featured two severe, cold–dry climatic downturns, the Last Glacial Maximum and Younger Dryas that profoundly affected human adaptation in North China. During the LGM archaeological evidence for human occupation of northern China is scant and North China’s earliest blade-based lithic industry, the Early Upper Paleolithic (EUP) flat-faced core-and-blade technology best known from Shuidonggou Locality 1 (SDG1) on the upper Yellow River, was replaced by a bipolar percussion technology better suited to lower quality but more readily available raw material. ==

“Researchers presented evidence that the initial rise in microblade use in North China occurs after 13,000 years ago, during the YD, from three key sites in west-central northern China: Dadiwan, Pigeon Mountain and Shuidonggou Locality 12 (SDG12). In this region composite microblade tools are more commonly knives than points. These data suggest the rise of microblade technology in Younger Dryas north-central China was mainly the result of microblades used as insets in composite knives needed for production of sophisticated cold weather clothing needed for a winter mobile hunting adaptation like the residentially mobile pattern termed ”serial specialist.” Limited time and opportunities compressed this production into a very narrow seasonal window, putting a premium on highly streamlined routines to which microblade technology was especially well-suited. ==

“It has been clear for some time that while microblades may have been around in north-central China since at least the LGM, they become prominent (i.e., chipped stone technology becomes ”microlithic”) only much later, with the YD. This sequence suggests a stronger connection between microblades and mobility than between microblades and hunting. If microblades were only (or mainly) for edging weapons, their rise to YD dominance would suggest an equally dramatic rise in hunting, making it difficult to understand why a much more demanding microblade technology would develop to facilitate the much less important pre-YD hunting. In any event, the SDG12 assemblage is at odds with the idea of a hunting shift. No more or less abundant than in pre-YD assemblages (e.g., QG3), formal plant processing tools suggest a continued dietary importance of YD plants, and there is no evidence for hunting of a sort that would require microblade production (i.e., of weaponry insets) on anything like the scale in which they occur. A shift to serial specialist provides a better explanation. ==

“Serial specialists are frequently forced to accomplish significant amounts of craftwork in relatively short periods of time. Microblade technology is admirably suited to such streamlined mass-production, and this is exactly what the SDG12 record indicates. The intensity with which SDG12 was used and the emphasis on communal procurement suggests a fairly short-term occupation by groups that probably operated independently during the rest of the year, almost certainly during the winter. SDG12 was most likely occupied immediately before that in connection with a seasonal ”gearing up” for winter, perhaps equivalent to the ethnographically recorded “sewing camps” of the Copper Inuit and Netsilik Inuit. ==

Yi Mingjie of the IVPP, one of the authors of the study, said: “Our study indicates that YD hunter-gatherers of north-central China were serial specialists, more winter mobile than their LGM predecessors, because LGM hunter-gatherers lacked the gear needed for frequent winter residential mobility, winter clothing in particular, and microblade or microlithic technology was central to the production of this gear. Along with general climatic amelioration associated with the Holocene, increasing sedentism after 8000 years ago diminished the importance of winter travel and the microlithic technology needed for the manufacture of fitted clothing.” ==

Dr. Robert L. Bettinger of the University of California – Davis, another author said: “We do not argue that microblades were not used as weapon insets (clearly they were), or that microblade technology did not originally develop for this purpose (clearly it might have). We merely argue that the YD ascendance of microblade technology in north-central China is the result of its importance in craftwork essential to a highly mobile, serial specialist lifeway, the production of clothing in particular. While microblades were multifunctional, this much is certain: of the very few microblade-edged tools known from north-central China all are knives, none are points. If microblades were mainly for weapons it should be the other way around”,

Bamboo Tools and the Scarcity of Advanced Stone Tools in East Asia

Kathleen Tibbetts of SMU wrote: “The long-held theory that prehistoric humans in East Asia crafted tools from bamboo was devised to explain a lack of evidence for advanced prehistoric stone tool-making processes. But can complex bamboo tools even be made with simple stone tools? A new study suggests the “bamboo hypothesis” is more complicated than conceived, says SMU archaeologist Metin I. Eren. [Source: Kathleen Tibbetts, Southern Methodist University (SMU), April 12, 2011 |::|]

“Researchers know that simple flaked “cobble” industries existed in some parts of the vast East and Southeast Asia region, which includes present-day China, Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, parts of Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Thailand, East Timor and Vietnam. Stone tool discoveries there have been limited to a few hand axes, cleavers and choppers flaked on one side, however, indicating a lack of more advanced stone tool-making processes, innovation and diversity found elsewhere, say the authors.

“The lack of complex prehistoric stone tool technologies has remained a mystery. Some researchers have concluded that prehistoric people in East Asia must have instead crafted and used tools made of bamboo — a resource that was readily available to them. Scientists have hypothesized various explanations for the lack of complex stone tools in East and Southeast Asia. On one hand, it’s been suggested that human ancestors during the early Stone Age left Africa with rudimentary tools and were then cut-off culturally once they reached East Asia, creating a cultural backwater. Others have suggested a lack of appropriate stone raw materials in East and Southeast Asia. In the new study, however, Bar-Yosef, Eren and colleagues showed otherwise by demonstrating that more complex stone tools could be manufactured on stone perceived to be “poor” in quality.

See Separate Article: EARLY PEOPLE IN SOUTHEAST ASIA factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University;; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw \=/ Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated April 2024