SECLUDED LIVES OF THE CHINESE EMPERORS

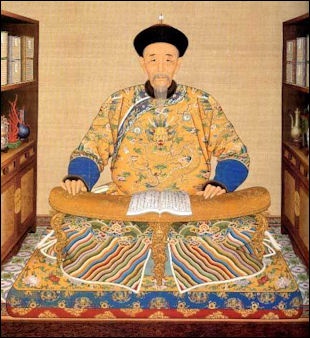

Qinf Emperor Kanxi studying

The Chinese emperors kept themselves secluded from their subjects and were largely confined to their palaces. Some emperors rarely left their palaces except to go hunting or visit their ancestors graves. The Ming dynasty ruler, Emperor Wam-li, virtually imprisoned himself within the Forbidden City with his wives and concubines. Even his ministers of state were not allowed to address him directly and whenever he traveled the roads were cleared so no one could see him.

The emperor often ate alone, attended only by his eunuchs. Meal times was often fixed at 8:00am for breakfast and 1:00pm for supper. With the exception of drinks and a snack in the evening, the emperor often consumed nothing else.

The royal physician was forbidden from touching the emperor directly. To check the emperor's pulse at a respectful distance, a member of the court attached a thread to emperor's wrist and the physician grasped the thread.

In the 16th century Matteo Ricci wrote: "The kings... abandoned the custom of going out in public...When they did leave the royal enclosure, they would never dare to do so without a thousand preliminary precautions. On such occasions the whole court was placed under military guard. Secret servicemen were placed along the route over which the King was to travel and on all roads leading into it. He was not only hidden from view, but the public never knew in which of the palanquins of the cortege he was actually riding. One would think he was making a journey through enemy country rather than among multitudes of his own subjects."

Emperors weren't the only ones who received this kind of treatment. Commoners had to kowtow (lay down forward on all fours and touch one's head to the ground) in the presence of high officials.

Some Emperors and high officials sometimes disguised themselves as ordinary people so the could learn what the masses were thinking.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: TANG, SONG AND YUAN DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com; CHINESE DYNASTIES AND RULERS factsanddetails.com; CHINESE EMPEROR AND IMPERIAL RULE IN ANCIENT CHINA factsanddetails.com; DOCUMENTS, SEALS AND MAPS OF THE CHINESE EMPEROR factsanddetails.com; EUNUCHS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CHINESE SCHOLAR-OFFICIALS AND THE IMPERIAL CHINESE BUREAUCRACY factsanddetails.com CHINESE LITERATI AND SCHOLAR-ARTIST-POETS factsanddetails.com; CHINESE IMPERIAL EXAMS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Imperial China (DK Classic History)” Amazon.com; “Imperial China, 900–1800" by F. W. Mote Amazon.com; “Chronicle of the Chinese Emperors: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial China” by Ann Paludan Amazon.com; “Chinese emperors from the Xia Dynasty to the Fall of the Qing Dynasty” by Ma Yan by Ma Yan and Beautifully Illustrated Amazon.com; “The Eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty” by Shih-Shan Henry Tsai ( Amazon.com; “The Forbidden City” by Geremie Barme Amazon.com; “Celestial Women: Imperial Wives and Concubines in China from Song to Qing” by Keith McMahon Amazon.com;

Imperial Chinese Concubines

Palace concert

Imperial concubinage wasn’t all it was made out to be. One character in the 18th century novel Dream of a Red Mansion said, “how much happier are those whose home is a hut in field, who eat salt and pickles and wear clothes of cotton, than she is who is endowed with wealth and rank, but separated from her flesh and blood.”

More than 200 Imperial concubines reportedly died on the orders of the 16th century emperor Shizon, Hoping to escape their fate, 16 members of Shizon’s harem snuck into his chamber to strangle him with a silken scarf and stab him with a hairpin. In the struggle the Emperor lost an eye but survived with the help of his Empress. The concubines were punished nu having their limbs pulled off thier bodies and their heads were displayed on poles.

There were eight levels of concubines. Concubines and eunuch often formed close friendships.

Emperors also had male consorts. According to legend the Han Dynasty Emperor Ai said he would rather cut off the sleeve of his robe than disturb his male lover who had fallen asleep on it. Some Chinese still refer to homosexuality as “the passion of the sleeve.”

Chinese Emperor's Sex Life

The Emperors had many women to keep them occupied. One emperor in the 11th century had 121 women (the nearest round number of one third of 365, the number of days in a year) at his immediate disposal, including one empress, three consorts, nine spouses, twenty-seven concubines, and eighty-one assistant concubines. See Sui Dynasty. Some emperors believed they could gain immortality form having sex with as many women as possible but never ejaculating. See Yellow Emperor.

Emperor Wu Of Jin (reigned 266 to 290 B.C.) let a goat choose his concubines Mark Oliver wrote in Listverse: “Emperor Wu dedicated most of his time to his harem. He would pull every pretty girl he could find out of her home to make her his concubine, especially preying on his officials’ daughters. This, for Emperor Wu, was important work—so much so that he made it a crime to get married until he was finished picking his concubines. By the end, Emperor Wu had more than 10,000 women in his harem. To choose his partner for the night, he would ride around in a cart drawn by goats. When the goats stopped, he’d sleep with whichever woman they’d brought him to. [Source: Mark Oliver. Listverse, January 12, 2017]

Emperor Xuanzong (reigned A.D. 713-756) had 40,000 concubines. Traditionally, in Xuanzong’s time, emperors would release their concubines when their reign came to an end. Since it often only took a couple of years for someone to get fed up and assassinate the king, that meant that being a concubine was only a temporary position. Xuanzong, however, stubbornly refused to die. His reign went on for 44 years, and his harem just kept getting bigger. By the end, he had over 40,000 women. Xuanzong almost certainly didn’t have time to meet them all, so instead, they just sat around learning poetry, mathematics, and the classics and taking care of mulberry trees. That doesn’t mean he stopped adding to his harem, though. When he was 60 years old, Xuanzong made his own son divorce his wife so that he could make his daughter-in-law one of his concubines.

Emperor Xuanzong (reigned A.D. 713-756) had 40,000 concubines. Traditionally, in Xuanzong’s time, emperors would release their concubines when their reign came to an end. Since it often only took a couple of years for someone to get fed up and assassinate the king, that meant that being a concubine was only a temporary position. Xuanzong, however, stubbornly refused to die. His reign went on for 44 years, and his harem just kept getting bigger. By the end, he had over 40,000 women. Xuanzong almost certainly didn’t have time to meet them all, so instead, they just sat around learning poetry, mathematics, and the classics and taking care of mulberry trees. That doesn’t mean he stopped adding to his harem, though. When he was 60 years old, Xuanzong made his own son divorce his wife so that he could make his daughter-in-law one of his concubines.

“Traditionally, in Xuanzong’s time, emperors would release their concubines when their reign came to an end. Since it often only took a couple of years for someone to get fed up and assassinate the king, that meant that being a concubine was only a temporary position.

“Xuanzong, however, stubbornly refused to die. His reign went on for 44 years, and his harem just kept getting bigger. By the end, he had over 40,000 women. Xuanzong almost certainly didn’t have time to meet them all, so instead, they just sat around learning poetry, mathematics, and the classics and taking care of mulberry trees.

“That doesn’t mean he stopped adding to his harem, though. When he was 60 years old, Xuanzong made his own son divorce his wife so that he could make his daughter-in-law one of his concubines. [Source: Mark Oliver. Listverse, January 12, 2017]

Emperors also had male consorts. According to legend the Han Dynasty Emperor Ai said he would rather cut off the sleeve of his robe than disturb his male lover who had fallen asleep on it. Some Chinese still refer to homosexuality as “the passion of the sleeve.” Imperial women also indulged themselves. Empress Wu Ze Tian was a 7th century ruler who was previously a nun and then a concubine and briefly changed the Tang dynasty’s name to Zhou. She had her own harem of men.

Chinese Emperor's Sexual Rotation Schedule

One of Emperor Yongzheng's Twelve Beauties

It was believed that organizing the Emperor's sex life into a regimented order was essential to maintaining the well-being of the entire Chinese empire. The great Chinese calendar clocks of the 10th century were not used to keep track of time but rather to decide the schedule, rotation and time for the women who slept with the Emperor. Secretaries kept record of the Emperor's sex life with brushes dipped in imperial vermillion.

In China and some other Asian countries age is determined from the moment of conception not from the moment of birth. The Imperial Chinese believed that women were most likely to conceive on the nights nearest the full moon, when the Yin, or female influence, was strong enough to match the potent Yang, or male force, of the Emperor. It was believed that on these nights children with strong virtues would be produced. As a result the empress and spouses slept with Emperor around the full moon and the lower ranking women, whose main function was to nourish the Emperor's Yang with their Yin, slept with him around the time of the new moon. [Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin]

A rotation described in the Record of the Rites of the Chou dynasty (1120-256 B.C.) was as follows: "The lower-ranking [women] come first, the higher ranking come last. The assistant concubines, eighty-one in number, share the imperial couch nine nights in groups of nine. The nine spouses and the three consorts are allotted one night to each group, and the empress also alone one night. On the fifteenth day of every month the sequence is complete, after which it repeats in reverse order." [Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin]

Some emperors kept the names of their favorite wives, consorts and concubines on jade tablets kept in their bed chambers. The most active emperors had 50 or more of these tablets. When an emperor selected the woman he wanted he turned over the tablet with her name on a teak table. A eunuch then rushed to the woman's chamber, took off her clothes to make sure she wasn't concealing a weapon, wrapped her in gold cloth, carried her through the palace since she could barely walk with her bound feet and deposited her at the foot of the emperor's bed. The eunuch then recorded the date to verify later whether or not the emperor was the father of any children born to the woman.

Imperial Chinese Court Life

Emperor travelling in a palanquin

In imperial times, visitors to the emperor were expected to drop to the floor and knock their foreheads on the floor nine times to show respect. Some emperors reportedly tested the loyalty of their ministers by bringing in a donkey and calling it horse and asking the minister what he thought. If the mister called it a donkey he was executed. If he called it a horse he was promoted.

Emperors liked to portray themselves as scholars and art lovers. Perhaps the best example of this was the Emperor Qianlong (1736-1796), regarded as China’s last great emperor. See Emperor Qianlong, Qing Dynasty.

Baixiyong were performers who entertained the court with acrobatics, singing, dancing, magic and feats of strength.

Often an emperor was served hundreds of dishes during meal time but ate only a few bites here and there. At banquets he ate at a table on a platform raised above the guests. A Jesuit priest who attended one of these banquets in 1727 wrote: “Every time the Emperor says a word...one must kneel down and hit one’s head on the ground. This has to be done every time someone serves him something to drink.”

Imperial Chinese Wealth

The emperors of China lived in luxury rivaled only by the Bourbons of France, the Romonavs of Russia, the Hapsburgs of Austria, and the Moguls of India.

A testimony to the Emperor's wealth is the contents of the Forbidden City in Beijing and the Palace Museum in Taiwan. All of the things kept in these places belonged to the Emperor. See Beijing and Taiwan.

The Chinese emperors used four-story umbrellas that looked like pagodas, were carried to places in sedan chairs accompanied by armies of servants and put their chop on documents with vermillion ink using a seal more valuable the treasuries of most states. Members of the court were buried with gold cloth placed over their face and rings on their fingers and shrouded with white silk embroidered with dragons and phoenixes.

In Imperial China, peasant sometimes owned land, but private property was generally regarded as a gift of the state.

Imperial Chinese Clothing

The members of the court had three sets of clothing: regular, court and ceremonial. Imperial clothes were made with silk, gold, sliver, pearls, jade, rubies, sapphires, coral, lapis lazuli, turquoise, agate, various kind of fragrant woods, kingfisher feathers and thread made from peacock feathers. Beginning in the Sui dynasty (581-618 A.D.) the emperor appropriated the color yellow and prohibited other people from wearing it based on a purported precedent set by the legendary Yellow Emperor.

The members of the court had three sets of clothing: regular, court and ceremonial. Imperial clothes were made with silk, gold, sliver, pearls, jade, rubies, sapphires, coral, lapis lazuli, turquoise, agate, various kind of fragrant woods, kingfisher feathers and thread made from peacock feathers. Beginning in the Sui dynasty (581-618 A.D.) the emperor appropriated the color yellow and prohibited other people from wearing it based on a purported precedent set by the legendary Yellow Emperor.

Imperial clothing accessories included belts, ceremonial hats, regular hats, hairpins, headdress ornaments, bracelets, thumb rings, fragrance pouches, purses, watches, rosaries, belts (regular, court and ceremonial), necklaces hat finials, hat decorations, silk purses, shoes for bound feet, hats withe jeweled knobs, headbands, silk kerchiefs, fans, rings, buttons, hooks, earnings, brooches and fingernail guards.

Robes were the most visible and decorated garments. They were usually made of silk and featured lavish colors, exquisite stitching and a variety of embroidered decorations and symbols. Most pieces that remain today date to the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). The Qings (Manchus) were horse people and many of their garments were designed for riding on horses. Many robes have long horseshoe-shaped cuffs because it was considered impolite to show one’s hands and fingers.

Leonard Yiu, a collector of tribal costumes and jewelry, came into the possession of a yellow dragon robe, which was worn by a member of the royal family during the Qing Dynasty in China (1644-1911, the last imperial dynasty). He told the Star of Malaysia: “While it was not worn by the emperor, it must’ve been worn by a member of the emperor’s immediate family...The condition is bad now but you can still see that the whole robe is woven. In fact, the motifs on the robe were not embroidered onto the robe, they were woven in when the fabric was woven. This technique is very, very difficult to duplicate. [Source: Brigitte Rozario, The Star (Malaysia), September 17, 2006]

“The tribes in China don’t carve wood, so all their artistry is focused on clothing and textiles. It is through their costumes that you can admire their culture and their artistry,” says Yiu. “The colour of the robe, imperial yellow, and the dragon motif with five claws, indicate something that could have been worn only by the emperor’s immediate family. I bought this in China about 15 years ago. Even then, it was not cheap. I think it was about RM15,000 ($4,900). Now, it could probably sell for RM100,000 ($328,000).” says the collector.

Symbols on Imperial Chinese Clothing

crane symbolized longevity

During the Qing dynasty the ranks of courtiers and bureaucrats were indicated by decorative designs on their costumes, the number of peacock feathers on their hats and the number of precious materials they were allowed to wear. For example, the formal over-robe worn by a first degree civil servant was embroidered with a crane while that of a second degree civil servant was embroidered with a golden pheasant. Robes of lower ranking officials were decorated with other animals. Color also indicated rank. Brilliant yellow was reserved for the Emperor. Muted yellows were worn by his underlings.

Beginning in 1759, emperors were required to wear 12 symbols of authority that included dragons, stars and symbols representing the ocean. The lower portion of a jacket often contained diagonal stripes signifying water and rolling waves, mountain peaks symbolizing the earth and mountains and dragons in the clouds representing air. At the neck was a gate to heaven. Fancy robes had nine dragons, an auspicious numbers, symbolizing power and virility.

Imperial Chinese Art Objects

Chinese art objects possessed by emperors included carved and decorative ink stones; Ju-it scepters (scepters that symbolized political and military power that were given to dignitaries and courtiers on different occasions); and miniature curio cabinets (elaborate multi-compartment boxes for storing things). Highly valued objects were made from animal horn (rhinoceros horn was particularly prized), silk, jade, ivory, lacquered softwoods, and polished hardwoods.

Among the items the emperors kept in miniature curio cabinets were small combs, tea containers, censers, incense, small knifes, nail files, forks, tweezers, brushes, pens, books, ink slabs, ink, ink cases, paper, brushes, brushwashers, brush-racks, water containers, glue boxes, seals, seal ink, and carved decorative pieces made from bamboo, wood, enamel, bronze, porcelain, ivory, gold, silver, rock-crystal and jade. The tiny compartments, shelves, drawers and boxes were often connected in elaborate, cryptic ways.

Imperial Tusu Wine New Year Ritual

Tusu Wine was a ritual wine used by the Chinese Emperor. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: ““In the first period of the Chinese New Year, the Qing emperor Qianlong annually greeted the New Year by holding a “First Stroke” ceremony at the Eastern Warmth Chamber in the Hall of Mental Cultivation. He used the “Gold Chalice of Eternal Stability” to drink “tusu” New Year’s wine, the goblet symbolizing the firmness of political authority, and lit the “Jade Candlestick of Constant Harmony” to beseech favorable weather for the coming year. The emperor then took the “Brush Verdant for Ten Thousand Years” to write auspicious phrases of blessing for the New Year, also opening an almanac for the year to pray for peace and prosperity throughout the land. Although the Qianlong emperor specifically ordered the Gold Chalice of Eternal Stability for the First Stroke cer-emony, the consumption of tusu wine had been a rite of the New Year passed down for many years. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw \=/]

Tusu Wine was a ritual wine used by the Chinese Emperor. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: ““In the first period of the Chinese New Year, the Qing emperor Qianlong annually greeted the New Year by holding a “First Stroke” ceremony at the Eastern Warmth Chamber in the Hall of Mental Cultivation. He used the “Gold Chalice of Eternal Stability” to drink “tusu” New Year’s wine, the goblet symbolizing the firmness of political authority, and lit the “Jade Candlestick of Constant Harmony” to beseech favorable weather for the coming year. The emperor then took the “Brush Verdant for Ten Thousand Years” to write auspicious phrases of blessing for the New Year, also opening an almanac for the year to pray for peace and prosperity throughout the land. Although the Qianlong emperor specifically ordered the Gold Chalice of Eternal Stability for the First Stroke cer-emony, the consumption of tusu wine had been a rite of the New Year passed down for many years. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw \=/]

“Tusu wine is first mentioned in Ge Hong’s Prescriptions for Acute Diagnoses from the Eastern Jin dynasty, and medical texts through the ages record a similar kind of alcoholic beverage, indicating it was a type of medicinal wine. Its recipe differs among texts but generally includes seven or eight herbs in various proportions. Its preparation usually involved placing rhubarb and herbs in a silken sachet suspended at the bottom of a well on New Year’s Eve. Brought out on New Year’s Day, it was steeped to make an alcoholic drink. Everyone in the family (both young and old) would face east and then take a drink to avoid illness and pestilence for the year.

“On New Year’s Day, the whole family would gather and drink tusu wine in the hope that nobody, young and old alike, would encounter misfortune or illness in the coming year. A tradition passed down over the ages, it gradually became an important custom to welcome the New Year. The spe-cial order for drinking tusu wine would start with the youngest family member and then proceed to the oldest, bestowing New Year’s blessings for the young and long life for the old. Tusu wine thus became a symbol of the New Year and longevity, as seen in traditional poetry and painting.

“At this time of celebration for the New Year, a special exhibition has been prepared on the subject of tusu wine and divided into three sections: “Explaining Tusu, ” “Writings About Tusu, ” and “Drinking Tusu.” Rare books, painting, calligraphy, and antiquities from the Qing palaces now in the National Palace Museum collection have been selected from the Qianlong and Jiaqing reigns to present the allusions and symbolic importance associated with tusu wine as well as the beauty of Qing court wine vessels related to the consumption of tusu.

““Tusu, ” as a symbol of the Chinese New Year and longevity, is often found in traditional poetry and painting about sending out the old and greeting the new. An example in the Qing dynasty is a tran-scription of “‘Xinyou’ New Year’s Eve” from 1741 in Dong Gao’s album Harmonious Poetry Sending Off the Year, in which appears a phrase that mentions tusu. In celebration of the Qianlong Emperor’s eightieth birthday, Jin Jian’s album entitled Prime Notes on Longevity features a collec-tion of imperial lines for seals. One poem on “‘Yichou’ New Year’s Day” includes the line, “Tusu extends life in a jade goblet, ” reflecting the idea of longevity. In the Jiaqing reign, Dong Gao’s al-bums Recording Beauty in the New Year and Sending the Old and Welcoming Auspiciousness fea-tures tusu in two paintings — “Tusu Joyous Drink” and “Tusu of Longevity” — that convey the idea of the New Year and long life, respectively. Also, Yao Wenhan’s “Joyous Celebration for the New Year” is a painting that depicts the moment in the New Year when tusu wine is prepared for elders using the Gold Chalice of Eternal Stability to offer blessings for longevity.

“The Qianlong emperor used the Gold Chalice of Eternal Stability to drink the first cup of tusu wine for the New Year. In Qianlong’s imperial poetry there appears the line “Tusu extends life in a jade goblet” and another on tusu wine in a jade cup. They indicate that, in addition to the Gold Chalice of Eternal Stability, wine cups and goblets made of jade were used for drinking tusu wine during New Year’s banquets at the Qing court to symbolize longevity. Gold and jade vessels made by the Qing court during the Qianlong reign include high-stem cups, handled goblets and cup-and-saucer sets either refined or complex in form. Also, depending on the material, various kinds of decoration appear, such as enameling and carving. Reflecting the beauty and craftsmanship of court objects, audiences can feel the “wine overflowing tusu cups” in the traditional festivities of the Chinese New Year.

Imperial Chinese Violence

Ming army in action

In ancient times the imperial court subjected traitors and spies to "five horses split the body," a punishment intended to destroy a person not only on earth but in the hereafter. Officials who committed and egregious offense were sometimes dismembered alive and skinned to death. Another particularly nasty imperial punishment was "death by a thousand cuts."

Emperors commonly killed their brothers, uncles, nephews and other relatives during their grab for power to eliminate rivals. Imperial daughters often died in the first two years of their life due to benign neglect. Chinese who said bad things about the emperor were sometimes punished by castration.

Families, friends and neighbors of the accused were often brutally punished along with the accused himself. See Tthe Qing Yongzheng Emperor.

Ancient Chinese soldiers often presented the head of enemy soldiers killed in battle to Emperor or his ministers or generals. Ths was done not for religious or ritualistic reasons but simply to prove the soldiers had performed their duty and thus claim their pay. Sometimes prisoners of war were sacrificed. Other times they were deported to a different part of the kingdom.

See Shang burials, Emperor Qin, Ming emperor Zhu Yuanzhang, Yongle Emperor.

Image Sources: Emperor and Palanqin, All Posters.com http://www.allposters.com/?lang=1 Search Chinese Art; Palace Concert, University of Washington; Ming era tribute, Dr. Robert Perrins; 7) Imperial Robe, Kent State University; Imperial Robe symbol, Kent State University; Others: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2016