WORLD'S EARLIEST PAPER, FROM CHINA

Early paper Chinese papermaking is over 2000 years old (paper has been found in 2nd century B.C. Chinese tombs). Before then some Chinese wrote on bamboo strips, turtle shells, oxen shoulder blades, and sheets of waste silk and Tibetans wrote on the smooth shoulder bones of goats.

According to legend, the first sheets of paper were made in A.D. 105 by Ts'ai Lun, a Chinese eunuch at the Imperial Chinese court, from mulberry leaves, old fish nets, hemp, tree bark, and rags. For the ancient Chinese paper was more than a material to write on. From at least the 5th century A.D. the Chinese made hats, shoes, belts, curtains and armor with arrow-resistant pleats from paper.

Professor Derk Bodde wrote: ““The formal invention of paper can be dated exactly in the year A.D. 105, and was the work of one who should surely be honored among the great contributors to human civilization. He was Ts'ai Lun, a man attached to the Chinese imperial court. Ts'ai Lun's biography in the history of his time describes his invention as follows: “In ancient times writing was generally on bamboo or on pieces of silk, which were then called chih [a Chinese word pronounced jer, which has since been used to mean paper]. But silk being expensive and bamboo heavy, these two materials were not convenient. Then Ts'ai Lun thought of using tree bark, hemp, rags, and fish nets. In the first year of the Yuan-hsing period (A.D. 105) he made a report to the emperor on the process of paper making, and received high praise for his ability. From this time paper has been in use everywhere and is called the "paper of Marquis Ts'ai." There is good reason to suppose that previous attempts to make paper, using raw silk, had already been going on, possibly as early as the third century B.C. What Ts'ai Lun seems to have done, however, was to develop an easy process for manufacture and, above all, to substitute cheaper materials in the place of the expensive silk. His achievement put paper within the reach of everyone. [Source: Derk Bodde, Assistant Professor of Chinese, University of Pennsylvania, November 8, 1942, Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu /=/]

Paper was so prized In imperial China that it was forbidden to step on it. Describing paper, the third century scholar Fu Hsien wrote, "Lovely and precious is this material/ Luxury but at a small price;/ Matter immaculate and pure in its nature/ Embodied in beauty and elegance incarnate,/ Truly it pleases men of letter."

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: FIRSTS, ACHIEVEMENTS AND THEMES IN CHINESE HISTORY factsanddetails.com; WORLD'S FIRST GUNPOWDER, BOMBS AND ROCKETS — FROM CHINA factsanddetails.com; CHINESE FIRSTS: TOILET PAPER, KITES, CHESS, AND CHAIRS factsanddetails.com : ANCIENT AND MEDIEVAL CHINESE TECHNOLOGY, ENERGY AND MACHINES factsanddetails.com; ANCIENT AND MEDIEVAL CHINESE SCIENCE: CHEMISTRY (ALCHEMY), ASTRONOMY, CLOCKS factsanddetails.com ; HISTORY OF MONEY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Books and Sources on Chinese Inventions: "Science and Civilization in China" by Joseph Needham ; The Wikipedia article is very long and thorough Wikipedia ; Science and Civilization by Joseph Needham in China Series Needham Research Institute ; Chinese Inventions Timeline Columbia University ;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: The Genius of China: 3,000 Years of Science, Discovery, and Invention by Robert K.G. Temple Amazon.com; Ancient China's Inventions, Technology and Engineering - Ancient History Book for Kids by Professor Beaver Amazon.com; Science and Civilisation in China. Volume 1: Introductory Orientations by Joseph Needham Amazon.com; The Shorter Science and Civilisation in China: an Abridgement of Joseph Needham's Original Text By Colin a Ronan Amazon.com; The Four Great Inventions of Ancient China: Their Origin, Development, Spread and Influence in the World by Jixing Pan Amazon.com

Ancient Papermaking in China

Paper is made of fibers that are mixed together when wet and bond when dry. In ancient times, paper was made by pounding rags, hemp, bark and other materials into fibrous pulps, which were dumped in water-filled vats. The fibrous pulps were suspended in the water and collected in a mold by workmen. The mold was then gently shaken, causing the thin layer of fibers to interlock, a process called matting. When the matted material dried it formed paper.

Chinese taken prisoners by Turks and Arabs after the conquest of Samarkand in the A.D. 8th century introduced the art of papermaking to the Muslim caliphs of Baghdad. By the 9th century Chinese paper craftsmen were working out of shops in the Middle East. Paper was not manufactured in Europe until the 11th century, almost 1,200 years after it was first used in China. The process of making it flowed to Europe from the Middle East via Byzantium and Spain.

The earliest known inks for writing were made in China and Egypt at least 2000 years ago.

History of Paper

Professor Derk Bodde wrote: “Of all Chinese contributions to the Western world, none can be more clearly traced in its beginnings in China, and then in its gradual spread across Asia to Europe, than can paper. In early times Chinese books were made of narrow vertical strips of bamboo. Many of these, tied together into a bundle formed one volume. The bulk and clumsiness of such a writing material is obvious. A Chinese philosopher of the fifth century B.C., Mo Tzu, by name, used to take along with him three cartloads of such bamboo books wherever he traveled. For writing small documents the Chinese used strips of silk. These were more convenient, but were too expensive for general use. Clearly a new writing material was needed. [Source: Derk Bodde, Assistant Professor of Chinese, University of Pennsylvania, November 8, 1942, Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu /=/]

“Following Ts'ai Lun's invention, paper spread with amazing speed throughout all the lands under Chinese domination. Thus in the arid deserts of Chinese Turkestan the world's earliest surviving examples of paper have in recent times been found. They date from within fifty years of Ts'ai Lun's death. In this and following centuries we find the Chinese doing almost everything with paper that was in later times to be done in other countries. Rag paper and hemp paper, paper of various plant fibers and of cellulose, paper sized and loaded to improve its quality for writing, wrapping paper and even paper napkins and toilet paper — all these were soon in general use. /=/

“From Central Asia paper pursued its triumphant way westward into the Arabic world, where its first manufacture can be exactly dated in the year 751. In that year, according to Arabic annals, at Samarkand, in the extreme west of Turkestan, the Arabs defeated a Chinese army and captured some of its soldiers. From some of them, who had formerly been paper makers, the Arabs first learned how to manufacture paper. /=/

“From Samarkand papermaking spread throughout the Arabic Empire, reaching Syria, Egypt (where it displaced papyrus), and Morocco. From there it finally entered Europe by way of Spain, where its manufacture is first recorded in A.D. 1150. From Spain, paper passed on to southern France, and the gradually to the rest of Europe, displacing parchment as it went. /=/

“The influence of paper upon the whole course of later Western civilization can hardly be overestimated. Without this cheap material it is unlikely that printing could ever have come into general use. Gutenberg's Bible, for example, which is probably the earliest European book printed from movable type, also happens to be one of the few books some of whose copies were printed on parchment instead of paper. It has been estimated that to produce one copy of the Bible on parchment, the skins of no less than 300 sheep were required. Had such conditions continued permanently, books would never have been available for more than the richest few, and printing might never have competed successfully with the older, and in some ways more artistic, process of copying manuscripts by hand. The debt of the world to Marquis Ts'ai is greater than the debt to many other whose names are better known. /=/

Article on early paper in China: “Paper” in “Commerce and Society in Sung China” by Shiba Yoshinobu (Ann Arbor, The University of Michigan Center for Chinese Studies, 1970), 103-111.

Marco Polo’s Description of Paper Money and How It is Made

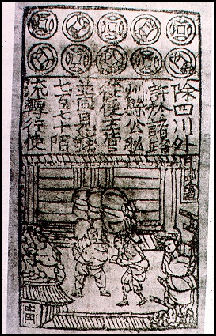

Early paper money “Chapter XXIV: How the Great Kaan Causeth the Bark of Trees, Made into Something Like Paper, to Pass for Money over All His Country” is a description of paper money and how it was made and circulated in Mongol China. According to Marco Polo's account: “Now that I have told you in detail of the splendour of this City of the Emperor’s, I shall proceed to tell you of the Mint which he hath in the same city, in the which he hath his money coined and struck, as I shall relate to you. And in doing so I shall make manifest to you how it is that the Great Lord may well be able to accomplish even much more than I have told you, or am going to tell you, in this Book. For, tell it how I might, you never would be satisfied that I was keeping within truth and reason! The Emperor’s Mint then is in this same City of Cambaluc, and the way it is wrought is

such that you might say he hath the Secret of Alchemy in perfection, and you would be right!

For he makes his money after this fashion. [Source: “Book of Ser Marco Polo: The Venetian Concerning Kingdoms and Marvels of the East,” translated and edited by Colonel Sir Henry Yule (London: John Murray, 1903)Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu /=/]

“He makes them take of the bark of a certain tree, in fact of the Mulberry Tree, the leaves of which are the food of the silkworms.. these trees being so numerous that whole districts are full of them. That which they take is a certain fine white bast or skin which lies between the wood of the tree and the thick outer bark, and this they make into something resembling sheets of paper, but black. When these sheets have been prepared they are cut up into pieces of different sizes. The smallest of these sizes is worth a half tornesel; the next, a little larger, one tornesel; one, a little larger still, is worth half a silver groat of Venice; another a whole groat; others yet two groats, five groats, and ten groats. /=/

“There is also a kind worth one bezant of gold, and others of three bezants, and so up to ten. All these pieces of paper are issued with as much solemnity and authority as, if they were of pure gold or silver; and on every piece a variety of officials, whose duty it is, have to write their names, and to put their seals. And when all is prepared duly, the chief officer deputed by the Kaan smears the Seal entrusted to him with vermilion, and impresses it on the paper, so that the form of the Seal remains printed upon it in red; the Money is then authentic. Anyone forging it would be punished with death. And the Kaan causes every year to be made such a vast quantity of this money, which costs him nothing, that it must equal in amount all the treasure in the world. /=/

Marco Polo’s Description of the Use of Mongol Paper

“Chapter XXIV” then describes how the paper money is circulated in Mongol China. According to Marco Polo's account: “With these pieces of paper, made as I have described, he causes all payments on his own account to be made; and he makes them to pass current universally over all his kingdoms and provinces and territories, and whithersoever his power and sovereignty extends. And nobody, however important he may think himself, dares to refuse them on pain of death. And indeed everybody takes them readily, for wheresoever a person may go throughout the Great Kaan’s dominions he shall find these pieces of paper current, and shall be able to transact all sales and purchases of goods by means of them just as well as if they were coins of pure gold. And all the while they are so light that ten bezants’ worth does not weigh one golden bezant. /=/

“Furthermore all merchants arriving from India or other countries, and bringing with them gold or silver or gems and pearls, are prohibited from selling to any one but the Emperor. He has twelve experts chosen for this business, men of shrewdness and experience in such affairs; these appraise the articles, and the Emperor then pays a liberal price for them in those pieces of paper. The merchants accept his price readily, for in the first place they would not get so good a one from anybody else, and secondly they are paid without any delay. And with this paper-money they can buy what they like anywhere over the Empire, whilst it is also vastly lighter to carry about on their journeys. And it is a truth that the merchants will several times in the year bring wares to the amount of 400,000 bezants, and the Grand Sire pays for all in that paper. So he buys such a quantity of those precious things every year that his treasure is endless, whilst all the time the money he pays away costs him nothing at all. Moreover, several times in the year proclamation is made through the city that anyone who may have gold or silver or gems or pearls, by taking them to the Mint shall get a handsome price for them. And the owners are glad to do this, because they would find no other purchaser give so large a price. Thus the quantity they bring in is marvellous, though these who do not choose to do so may let it alone. /=/

“Still, in this way, nearly all the valuables in the country come into the Kaan’s possession. When any of those pieces of paper are spoilt.. not that they are so very flimsy neither – the owner carries them to the Mint, and by paying three percent on the value he gets new pieces in exchange. And if any Baron, or anyone else soever, hath need of gold or silver or gems or pearls, in order to make plate, or girdles, or the like, he goes to the Mint and buys as much as he list, paying in this paper-money. /=/

“Now you have heard the ways and means whereby the Great Kaan may have, and in fact has, more treasure than all the Kings in the World; and you know all about it and the reason why. And now I will tell you of the great Dignitaries which act in this city on behalf of the Emperor.” /=/

Early Printing in China

Professor Derk Bodde wrote: “The noble sequel to paper in China was printing. As in the case of most major advances in human civilization, this invention was not the work of any single individual. It came as a climax to several separate processes, developed over a number of centuries. One of these was the invention and spread of paper itself, the significance of which has just been described. Another was the development of a suitable ink. [Source: Derk Bodde, Assistant Professor of Chinese, University of Pennsylvania, November 8, 1942, Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu /=/]

“A third was the process of making what are called rubbings or squeezes. This is a Chinese technique for obtaining on paper exact copies of inscriptions that have been cut on stone monuments and tablets. A sheet of moistened tissue paper is closely fitted upon the face of the engraved stone. The outer surface of this paper is then rubbed with an ink pad so that all parts of the paper touching the raised portions of the underlying stone are inked black. The parts of the paper that fit into the cutout depressions do not receive ink and are left white. Thus an exact black-and-white paper copy of the original inscription is obtained. The Chinese developed this technique of making rubbings because of their eagerness to obtain exact copies of their classics, which were often inscribed on stone monuments. /=/

“Most important of all the forerunners of printing was probably the Chinese use of stamp seals. Such seals first appear in human civilization in Mesopotamia, where seals with pictures on them played an important part in man's first development of a system of writing. In China seals began to be used about the third century B.C. At first they served the purpose, as in Mesopotamia, of personally identifying their owners. Even to this day, a Chinese, when endorsing a bank check in China, must not only sign his name, but also stamp the check with a personal seal bearing his name in printed characters. The seal of the author, which he used for this purpose when he lived in China, is shown under his name on the cover of this pamphlet. /=/

“In China, as in Mesopotamia, such seals were in the beginning used to stamp impressions on clay. From about the sixth century A.D. onward, however, the Chinese began to stamp their seals in ink, in order to print short inscriptions on paper, in a way similar to our modern rubber stamps. It is from such inked impressions that the true printing of later times gradually developed. /=/

“At about the same time, Buddhist and Taoist priests in China began to use such seals. Their seals were only a few inches square and were used to print magical charms and inscriptions by the hundreds. Here was first developed the idea of rapid duplication, an inherent principle of printing. All that yet remained to be done was to enlarge the size of such seals so that many rather than few words could be reproduced at one time. Then genuine printing would be at hand." /=/

First Wood Block Printing in China

The Chinese are credited with inventing wood block printing in the A.D. 3rd century, and printing presses in the 11th century. Before giving China full credit for inventing printing it must pointed out the wood-block printing invented by the Chinese was very different from the movable type printing used by Gutenberg to print his famous Bible in the 15th century.

The Chinese are credited with inventing wood block printing in the A.D. 3rd century, and printing presses in the 11th century. Before giving China full credit for inventing printing it must pointed out the wood-block printing invented by the Chinese was very different from the movable type printing used by Gutenberg to print his famous Bible in the 15th century.

"Making repeated images for printing textiles from a carving on wood was an ancient folk art," Daniel Boorstin in "The Discoverers". "At least as early as the third century the Chinese had developed an ink that made clear and durable impressions from these wood blocks. They collected the lamp black from burning oils or woods and compounded it into a stick, which then dissolved to the black liquid that we call India ink." Block printing on paper was widely developed in the Tang dynasty. The emperor's library in the 7th century held about forty thousand manuscript rolls. [Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin]

The idea for wood-block printing began when someone decided to take the handle off a wooden stamp so that printing surface could be placed face up on a table. A sheet of paper then could be laid on the inked block, rubbed with a brush, to produce a print. The making of large woodcuts became possible when several of these "wooden stamps" were placed side by side.

Buddhism played an instrumental role in the development of block printing in China in the A.D. 7th century. Buddhists believe they can earn "merit" (brownie points on the path to Nirvana) by duplicating the image of Buddha and repeating sacred texts. The more images or texts a Buddhist makes the more merit he earns. Buddhists use rubbings from stones, seals, stencils and small wooden stamps to make images over and over. For them printing is perhaps the easiest, most efficient and most cost effective way to earn merit. The earliest examples of Chinese printing were destroyed during a crackdown on Buddhism in 845 when temples were destroyed and a quarter of a million nuns and monks were forced to flee their monasteries.

Chinese ideograms are not well suited for movable type. There are so many Chinese characters it is difficult to make multiple copies of them and to categorize them in a way that is easy to retrieve. Roman letters are better suited for movable type because there are many fewer letters. Chinese ideograms have a couple of advantages over Roman letters when it comes to printing. Their intricate forms are more interesting for carvers to make and their large size makes them easier to align on a page and grasp and put into place with the fingers. [Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin]

Book Printing in China

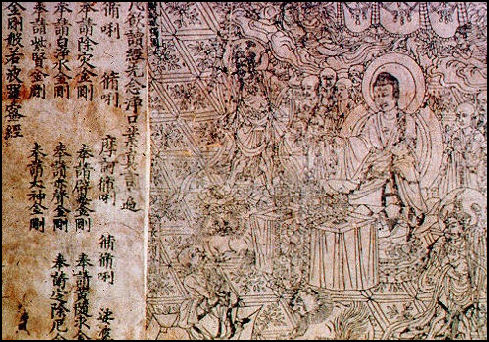

Professor Derk Bodde wrote: “It is definitely known that actual books were printed in China during the ninth century, and probably such printing goes back considerably earlier. The world's oldest existing printed book is a Buddhist sacred text, dated in the year A.D. 868, and beautifully printed in Chinese characters. It was recovered some forty years ago from a cave in Northwest China, just at the point where the great Silk Road leaves China proper to plunge into the deserts of Central Asia. This book was not folded into pages like our modern books, but was a single roll of paper 16 feet long. Its dedication states that it was printed by a certain Wang Chieh "for free general distribution, in order in deep reverence to perpetuate the memory of his parents." [Source: Derk Bodde, Assistant Professor of Chinese, University of Pennsylvania, November 8, 1942, Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu /=/]

“Less than a century later comes the first example of really large-scale book printing in China. This achievement was the printing of nine of the major Chinese classics in 130 volumes. It was carried out between the years A.D. 932 and 953 under the direction of a famous official named Feng Tao. From this time onward the flood of printing became ever greater. One modern writer has even estimated that up to the year 1800, more books were printed in China than in the entire rest of the world put together.” /=/

Oldest Book in China

The world's oldest surviving book, the Diamond Sutra, was printed with wooden blocks in China in A.D. 868. It consists of Buddhist scriptures printed on seven 2½-foot-long, one-foot-wide sheets of paper pasted together into one 16-foot-long scroll. Part of the Perfection of Wisdom text, a Mahayanist sermon preached by Buddha, it was found in cave in Gansu Province in 1907 by the British explorer Aurel Stein, who also found well-preserved 9th century silk and linen paintings.

In Imperial times, the Chinese preferred handwritten calligraphy over printing for important texts. Printing was used by those who could not afford anything better. In 932 a Chinese prime minister wrote: "We have seen... men from Wu and Shu who sold books that were printed from blocks of wood. There were many different texts, but there were among them no orthodox Classics [of Confucianism]. If the Classics could be revised and thus cut in wood and published, it would be a very great boon to the study of literature."

The revival of Confucianism during the Chinese Renaissance of the Song dynasty (A.D. 960-1127) is partly attributed to the printing of Confucian texts which helped spread the word of the philosophy to a greater number of people. By the end of the 10th century scholars printed the first of the great Chinese dynastic histories, consisting of several hundred volumes, and Buddhist monks printed the Tripitaka, the whole Buddhist canon with 5,048 volumes and 130,000 pages. In 1019, the 4,000-volume Taoist cannon was printed. In the 11th century Muslims in China printed calendars and almanacs while the Koran continued to be made by hand.

world's oldest surviving book, the Diamond Sutra,

Invention of Movable Type in China

In the early tenth century, texts began to be printed with copper plates instead of wooden blocks. Between 1041 and 1048, a Song dynasty historian wrote: "Pi Shêng, a man of the common people, invented movable type. His method was follows: He took sticky clay and cut it in characters as thin as the edge of a copper coin. Each character formed as if it were a single type. He baked them in the fire to make them hard. He had previously prepared an iron plate and he covered this plate with a mixture of pine resin, wax and paper ashes."

"When he wished to print," the historian continued. "He took an iron frame and set it on the iron plate. In this he placed the type, set close together. When the frame was full, the whole made one solid block of type. He then placed it near the fire to warm it. When the paste (at the back) was slightly melted, he took a smooth board and pressed it over the surface, so that the block of type became as even as a whetstone...for printing hundreds or thousands of copies, it was divinely quick."

The Koreans later developed a more sophisticated and adaptable method of movable type, but they failed to incorporate it with the Hangul (Korean) alphabet, which wasn't invented until the early 15th century. There is some evidence that Gutenberg got the idea for the technology on his printing press from the Portuguese who in turn got it from the Chinese.

Some regard the Phaistos Disk, found in the ruins of 3700-year-old Palace of Phaistos in Crete, as the earliest example of printing. The six-inch, baked-clay disk contains 241 pictorial design consisting of 45 different letters arranged in a spiral formation. The symbols were placed on the disk with sets of punches, one for each symbol, using the same concept as movable type.

History of Movable Type Printing

Professor Derk Bodde wrote: ““All that has hitherto been described refers only to block printing, that is, to printing in which a single block of wood is engraved for each page of the book printed. The first invention of separate movable type, however, is also Chinese. It is the work of a simple artisan named Pi Sheng. Between the years 1041 and 1049 he made a font of movable type of baked clay. In later centuries types made from wood and from various metals replaced such clay types. The use of metal was particularly developed in Korea in the fifteenth century. In China, however, features inherent in the nature of the Chinese script, as well as certain social and artistic attitudes, long prevented movable type from gaining a popularity equal to that of block printing. Despite its early invention, therefore, such type has come into general use in China only during the last few decades. [Source: Derk Bodde, Assistant Professor of Chinese, University of Pennsylvania, November 8, 1942, Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu /=/]

“At the same time that these developments in movable type were making their appearance in China and surrounding countries, the earlier Chinese invention of block printing was slowly pushing its way toward the Western world. From Turkestan it passed to Persia, where it was known in 1294, and then to Egypt. In Europe itself, we find that the earliest dated example of block printing is a small picture of St. Christopher, accompanied by two lines of text, which was made in the year 1423. Other similar undated pictures also exist, however, probably from a period a few decades earlier. Most of them came from southern Germany. /=/

“It is not likely that European block printing came as an independent development. Indeed, the beginnings of block printing in Europe can with good probability be traced to several Chinese influences. Among these may have been playing cards, which had long been printed in China, and which first appear in Europe in 1377. Another may have been the technique of decorating textiles by means of stamped designs, a technique which gained great popularity in Europe in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. /=/

“Most important of all, however, was probably the first European acquaintance with printed paper money. Such money began to be printed for the first time in world history in China during the tenth century. It was continued during the next two hundred fifty years, and taken over by the Mongols during their rule over China (1280-1367). Owing to several disastrous experiences with currency inflation, caused by inadequate metal backing for the paper money, the Chinese gave up its use after their expulsion of the Mongols in 1367. During the Mongol rule, however, paper money was being printed in China at the rate of no less than 37 million separate notes a year. Its use spread as far west as Persia, and it is admiringly described by at least eight pre-Renaissance European writers, including Marco Polo. It is difficult to suppose, therefore, that among thoughtful Europeans of the time, there were not some who did not see the possibilities of this strikingly successful example of mass-scale printing, and did not try in their turn to experiment along similar lines. /=/

“In Europe, as in China, block printing was followed by printing with movable type. The first major example of such European printing by means of movable type was Gutenberg's Bible. This appeared about 1456, only twenty-odd years after the earliest dated block printing of 1423. No certain proof has yet been found linking this mighty achievement with the similar Chinese invention of movable type more than four hundred years earlier, though such a link is not impossible. But in any case it seems evident that printing with movable type in Europe had a connection with the earlier development of block printing, which itself stems back to China. The mere fact that there already existed a process for duplicating books rapidly and inexpensively must have operated, in Europe as in China, as a spur toward devising a still easier method. In Europe the invention of movable type quickly displaced block printing entirely. That this did not happen in China does not mean that the Chinese are more conservative or "backward" than Westerners. It is primarily due to differences between our alphabetic script and the written characters of the Chinese, and not to different ways of thinking between the two races. /=/

Impact of Printing on Chinese Philosophy

Lynda Shaffer wrote: “The impact of printing on China was in some ways very similar to its later impact on Europe. For example, printing contributed to a rebirth of classical (that is, preceeding the third century CE) Confucian learning, helping to revive a fundamentally humanistic outlook that had been pushed aside for several centuries. [Source: Lynda Shaffer, "China, Technology and Change", World History Bulletin, Fall/Winter 1986/87; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu /=/]

“After the fall of the Han dynasty (BCE 201-220 CE), Confucianism had lost much of its credibility as a world view, and it eventually lost its central place in the scholarly world. It was replaced by Buddhism, which had come from India. Buddhists believed that much human pain and confusion resulted from the pursuit of illusory pleasures and dubious ambitions: enlightenment and, ultimately, salvation would come from a progressive disengagement from the real world, which they also believed to be illusory. This point of view dominated Chinese intellectual life until the ninth century. Thus the academic and intellectual comeback of classical Confucianism was in essence a return to a more optimistic literature that affirmed the world as humans had made it. /=/

“The resurgence of Confucianism within the scholarly community was due to many factors, but printing was certainly one of the most important. Although it was invented by Buddhist monks in China, and at first benefited Buddhism, by the middle of the tenth century printers were turning out innumerable copies of the classical Confucian corpus. This return of scholars to classical learning was part of a more general movement that shared not only its humanistic features with the later Western European Renaissance, but certain artistic trends as well. /=/

“Furthermore, the Protestant Reformation in Western Europe was in some ways reminiscent of the emergence and eventual triumph of Neo-Confucian philosophy. Although the roots of Neo-Confucianism can he found in the ninth century, the man who created what would become its most orthodox synthesis was Zhu Xi (Chu Hsi, 1130-1200). Neo-Confucianism was significantly different from classical Confucianism, for it had undergone an intellectual and political confrontation with Buddhism and had emerged profoundly changed. It is of the utmost importance to understand that not only was Neo-Confucianism new, it was also heresy, even during Zhu Xi's lifetime. It did not triumph until the thirteenth century, and it was not until 1313 (when Mongol conquerors ruled China) that Zhu Xi's commentaries on the classics became the single authoritative text against which all academic opinion was judged. /=/

“In the same way that Protestantism emerged out of a confrontation with the Roman Catholic establishment and asserted the individual Christian's autonomy, Neo-Confucianism emerged as a critique of Buddhist ideas that had taken hold in China, and it asserted an individual moral capacity totally unrelated to the ascetic practices and prayers of the Buddhist priesthood. In the twelfth century Neo-Confucianists lifted the work of Mencius (Meng Zi, 370-290 BC) out of obscurity and assigned it a place in the corpus second only to that of “The Analects” of Confucius. Many facets of Mencius appealed to the Neo-Confucianists, but one of the most important was his argument that humans by nature are fundamentally good. Within the context of the Song dynasty, this was an assertion that morality could be pursued through an engagement in human affairs, and that the Buddhist monks' withdrawal from life's mainstream did not bestow upon them any special virtue. /=/

Impact of Printing on Chinese Politics

Lynda Shaffer wrote: ““The importance of these philosophical developments notwithstanding, printing probably had its greatest impact on the Chinese political system. The origin of the civil service examination system in China can be traced back to the Han dynasty, but in the Song dynasty government-administered examinations became the most important route to political power in China. For almost a thousand years (except the early period of Mongol rule), China was governed by men who had come to power simply because they had done exceedingly well in examinations on the Neo-Confucian canon. At any one time thousands of students were studying for the exams, and thousands of inexpensive books were required. Without printing, such a system would not have been possible. [Source: Lynda Shaffer, "China, Technology and Change", World History Bulletin, Fall/Winter 1986/87; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu /=/]

“The development of this alternative to aristocratic rule was one of the most radical changes in world history. Since the examinations were ultimately open to 98 percent of all males (actors were one of the few groups excluded), it was the most democratic system in the would prior to the development of representative democracy and popular suffrage in Western Europe in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. (There were some small-scale systems, such as the classical Greek city-states, which might be considered more democratic, but nothing comparable in size to Song China or even the modern nation-states of Europe.)”/=/

Chinese Engraved Block and Wooden Movable-Type Printing — UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage

China Engraved Block Printing Technique was inscribed on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List in 2009. According to UNESCO: “The traditional China engraved block printing technique requires the collaboration of half a dozen craftspeople possessed of printing expertise, dexterity and team spirit. The blocks themselves, made from the fine-grained wood of pear or jujube trees, are cut to a thickness of two centimeters and polished with sandpaper to prepare them for engraving. Drafts of the desired images are brushed onto extremely thin paper and scrutinized for errors before they are transferred onto blocks. The inked designs provide a guide for the artisan who cuts the picture or design into the wood, producing raised characters that will eventually apply ink to paper. First, though, the blocks are tested with red and then blue ink and corrections are made to the carving. Finally, when the block is ready to be used, it is covered with ink and pressed by hand onto paper to print the final image. Block engraving may be used to print books in a variety of traditional styles, to create modern books with conventional binding, or to reproduce ancient Chinese books. A number of printing workshops continue this handicraft today thanks to the knowledge and skills of the expert artisans. [Source: UNESCO]

Wooden Movable-type Printing of China was inscribed on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List in 2010. One of the world’s oldest printing techniques, wooden movable-type printing is maintained in Rui’an County, Zhejiang Province, where it is used in compiling and printing clan genealogies. Men are trained to draw and engrave Chinese characters, which are then set into a type-page and printed. This requires abundant historical knowledge and mastery of ancient Chinese grammar. Women then undertake the work of paper cutting and binding, until the printed genealogies are finished.

The movable characters can be used time and again after the type-page is dismantled. Throughout the year, craftspeople carry sets of wooden characters and printing equipment to ancestral halls in local communities. There, they compile and print the clan genealogy by hand. A ceremony marks the completion of the genealogy, and the printers place it into a locked box to be preserved. The techniques of wooden movable-type printing are transmitted through families by rote and word of mouth. However, the intensive training required, the low income generated, popularization of computer printing technology and diminishing enthusiasm for compiling genealogies have all contributed to a rapid decrease in the number of craftspeople. At present, only eleven people over 50 years of age remain who have mastered the whole set of techniques. If not safeguarded, this traditional practice will soon disappear.

Image Sources: 1) Compass, Pandaamerica; 2) Fire oxen, University of Washingon; 3) Early bronze gun, University of Washingon; Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu /=/; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2021