NINGXIA

Ningxia NINGXIA, officially the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (NHAR) often referred to as “Ning”, is barren, windswept area of China. The landscape is dominated by mountains with stony slopes and eroded gullies and ravines. Sheep and goats forage for grass. Marijuana grows wild. The Great Wall of China winds through sections of the region. Here the wall is mostly made of tamped earth rather than stones. Some people check out the sections on the western flanks of the Helan Mountains.

About a third of the population of Ningxia are Hui Muslims. There are parts of southern Ningxia that are 80 percent Hui. Hui are Muslim Han Chinese, who are regarded with some suspicion by both non-Muslim Chinese and non-Chinese Muslims. They are found throughout China bu are most heavily concentrated in Ningxia.

Formerly a province, Ningxia was incorporated into Gansu in 1954 but, in 1958, broke off from Gansu and was reconstituted as an autonomous region for the Hui people. It is among the poorest areas of China. It is not unusual for a family of seven to live on less than US$100 a year in places that are void of good farming or grazing land, living in a two-room mud hut with raised platforms for beds, wearing clothes donated to them by other Chinese.

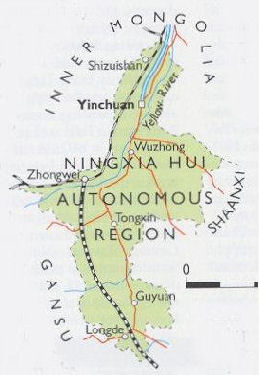

Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region is one of the smallest and least populated province-like divisions of China. It covers 66,400 square kilometers (25,637 square miles) and has a population density of 94 people per square kilometer. According to the 2020 Chinese census the population was around 7.2 million. About 59 percent of the population lives in urban areas. Yinchuan is the capital and largest city, with about 2.5 million people. Hui make up 38 percent of the population of Ningxia; Han China 62 percent. Maps of Ningxia: chinamaps.org

The population of Ningxia was 7,202,654 in 2020; 6,176,900 in 2010; 5,486,393 in 2000; 4,655,451 in 1990; 3,895,578 in 1982; 759,000 in 1947; 978,000 in 1936-37; 1,450,000 in 1928; 303,000 in 1912. [Source: Wikipedia, China Census]

Like Chinese provinces, an autonomous region has its own local government, but an autonomous region — theoretically at least — has more legislative rights. An autonomous region is the highest level of minority autonomous entity in China. They have a comparably higher population — but not necessarily a majority — of the minority ethnic group in their name. Some of them have more Han Chinese than the named ethnic group. There are five province-level autonomous regions in China: 1) Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region for the Zhuang people, who make up 32 percent of the population; 2) Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (Nei Mongol Autonomous Region) for Mongols, who make up only about 17 percent of the population; 3) Tibet Autonomous Region Autonomous Region (Xizang Autonomous Region) for Tibetans, who make up 90 percent of the population; 4) Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, for Uyghurs, who make up 45.6 percent of the population; and 5) Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, for the Hui, who make up 36 percent of the population. [Source: Wikipedia]

Geography and Climate of Ningxia

Ningxia map The Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region is landlocked and located at the middle and upper reaches of the Yellow River in northwest China. It borders Gansu Province to the south, Shanxi Province to the east, and Inner Mongolia to the north. Ningxia is sparsely settled, mostly desert and lies partially on the Loess Plateau and in the vast plain of the Yellow River. The Great Wall of China is situated along its northeastern boundary. Ningxia's deserts include the Tengger desert in Shapotou.and the Badain Jaran Desert, which is primarily in Inner Mongolia and regarded as part of the Gobi Desert.

The Yellow River flows through Ningxia. Over the years an extensive system of canals has been built. Extensive land reclamation and irrigation projects have made increased cultivation possible. The northern section, through which the Yellow River flows, supports the best agricultural land. A railroad, linking Lanzhou with Baotou, crosses the region. A highway has been built across the Yellow River at Yinchuan.

The Yellow River flows through 12 cities and counties in central and north Ningxia. It brings rich water resource to Ningxia and makes Yinchuan Plain the most affluent area throughout the autonomous region. The Yinchuan plain has been called the “Eden of the Northern Wastes”. Another saying goes, “The Yellow River Brings prosperity to Ningxia”.

Ningxia is 1,200 kilometers (750 miles) from the sea and has a continental climate with average summer temperatures rising to 17 to 24 °C (63 to 75 °F) in July and average winter temperatures dropping to between −7 to −15 °C (19 to 5 °F) in January. Seasonal extreme temperatures can reach 39 °C (102 °F) in summer and −30 °C (−22 °F) in winter. The diurnal temperature variation can reach above 17 °C (31 °F), especially in spring. Annual rainfall averages from 190 to 700 millimeters (7.5 to 27.6 inches), with more rain falling in the south of the region.

See Separate Articles GOBI DESERT factsanddetails.com ; Shaanxi Loess Region, See Separate Article LAND AND GEOGRAPHY OF CHINA factsanddetails.com

History of Ningxia

Ningxia and its surrounding areas were incorporated into the Qin Dynasty (221-207 B.C.) as early as the 3rd century B.C. Throughout the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. to A.D. 220) and the Tang Dynasty (618-906) there were several large cities established in the region, and by the 11th century the Tangut tribe had established the Western Xia Dynasty on the outskirts of the then Song Dynasty (960-1279). Jews also lived in Ningxia, as evidenced by the fact that, after a major flood destroyed Torah scrolls in Kaifeng, a replacement was sent to the Kaifeng Jews by the Ningbo and Ningxia Jewish communities.

Ningxia then came under Mongol domination after Genghis Khan conquered Yinchuan in the early 13th century. After the Mongols departed and its influences faded, some Turkic-speaking Muslims also began moving into Ningxia from the west. The Muslim Rebellion of the 19th century occurred here.

In 1914, Ningxia was merged with the province of Gansu; in 1928, however, it was detached and became a province. Between 1914 and 1928, the Xibei San Ma (literally "three Mas of the northwest") ruled the provinces of Qinghai, Ningxia and Gansu. Muslim Kuomintang General Ma Hongkui was the military Governor of Ningxia and had absolute authority in the province. A 8.6-magnitude earthquake in Gansu and Ningxia in 1920 killed around 180,000 people mostly in Ningxia. In 1958, Ningxia formally became an autonomous region of China. In 1969, Ningxia received a part of the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region, but this area was returned in 1979.It is nearly coextensive with the ancient kingdom of the Tangut people, whose capital was captured by Genghis Khan in the early 13th century.

A number of Chinese artifacts dating from the Tang Dynasty (618-906) and Song Dynasty (960-1279), some of which had been owned by Emperor Zhenzong were excavated and then came into the hands of Ma Hongkui, who refused to publicize the findings. Among the artifacts were a white marble tablet from the Tang Dynasty (618-906), gold nails, and bands made out of metal. It was not until after Ma passed away, that his wife went to Taiwan in 1971 from America to bring the artifacts to Chiang Kai-shek, who turned them over to the Taipei National Palace Museum.

Environmental Problems in Ningxia

Desertification is serious problem in many parts of Ningxia Some places have not received significant rain for years, making farming impossible, and are being swallowed up by desert. There are places that are so dry that wells yield a single bucket of water a day and that bucket provides all the water used for drinking and cooking for a couple of weeks, with no water left over for cleaning or watering crops.

In the late 1990s, tens of thousands of people from villages mostly in poor southern Ningxia were resettled to 215,000 acres of newly irrigated land near the Yellow River in north central China at a cost of about US$325 million. About 70 percent of those affected are Huis. Planners had originally hope to resettle a million people (20 percent of Ningxia's total population) but there was enough money available to handle that many people.

The Ningxia ecosystem is one of the least studied regions in the world. Significant irrigation supports the growing of wolfberries, a commonly consumed fruit throughout the region. On 16 December 1920, the Haiyuan earthquake, 8.6 magnitude, at 36.6°N 105.32°E, initiated a series of landslides that killed an estimated 200,000 people. Over 600 large loess landslides created more than 40 new lakes. In 2006, satellite images indicated that a 700 by 200-meter fenced area within Ningxia — 5 kilometers (3.1 miles) southwest of Yinchuan, near the remote village of Huangyangtan — is a near-exact 1:500 scale terrain model reproduction of a 450 by 350-kilometer area of Aksai Chin bordering India, complete with mountains, valleys, lakes and hills. Its purpose is as yet unknown.

Silk Road Sites in Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region

Silk Road Sites in Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region: 1) Historic City of Guyuan, Guyuan City (N36 06 00 E106 28 30); 2) Cemetery of Northern Dynasties and Sui and Tangy Dynasty in Guyuan (N35 58 34 E106 13 59); 3) Site of Kaicheng, Guyuan City (Coordinates: N35 57 00 E106 03 30); 4) Mount Xumi Grottoes (Coordinates: N36 00 00 E106 00 00)

Guyuan (300 kilometers northwest of of Xian, 200 kilometers east of Lanzhou) is situated in southernmost part of Ningxia near Gansu. It is the site of Mount Sumeru Grottoes, one of the ten most famous grottoes in China, and has a population of 1bput 1.1 million people. Because of its importance of its transportation to the west and north, Guyuan was a war gate where Chinese soldiers trained and prepared to fight with northwestern minorities. In the Tang dynasty, most of the Silk Road merchants from Central Asia had to pass through this gate then went to the Chang’an (Xian). According to the First Founder's Biography in History of Yuan Dynasty, Genghis Khan died in Liupan Mountain in Guyuan in 1227AD, after a war with the Xixia dynasty for two decades. [Source: Wikipedia]

Xumishan Grottoes (250 kilometers south of Yinchuan, 175 kilometers east of Lanzhou) were carved out of red sandstone cliffs and decorated with Buddhist statues between the 5th and 10th centuries, with the work most likely done by local artisans and monks and funded by merchants and nobles. The 130 or caves are located mostly in eight clusters spread out over a 1.5-kilometer-long area. Xumishan is a Chinese-language variation of “Mount Sumeru," the Sanskrit name of the holy Buddhist mountains at the center of the universe.

About half the grottoes have nothing in them. They are believed to have been used by monks for mediation or study. The others have wall paintings and statues, many with Indian and Central Asian influences. The biggest sculpture is a 20-meter-high Maitreya, Buddha of the Future. Other Maitreya can be found in other grottoes. Wind, sand and human occupation have taken their toll over the centuries. Only about 10 percent of the caves are in good condition. Restoration work by the Chinese relied heavily on concrete.

Yinchuan

Yinchuan (1,130 kilometers west of Beijing) is the capital and largest and most important city in Ningxia, with about 2.5 million people. It was once the home of the mysterious Xia civilization. Yinchuan lies on the Yellow River. The city has long depended on the river for water but these days its often little more than a narrow channel.

There are some unique local products and souvenirs. The “Five Treasures of Ningxia” refers to special products in five colors, including the fruit of Chinese wolfberry in red, licorice root in yellow, Helan stone in blue, beach-sheepskin in white and the black moss in black. In addition, rice, red melon seed, fish, melons and fruits, “Ningxia Red” Chinese wolfberry wine, “Western Xia” red wine produced in Ningxia, are all well-known as good gifts for friends.

Kyle Haddad-Fonda wrote in Foreign Policy: Yinchuan is situated on the loess-covered floodplain of the Yellow River. Its remoteness has not deterred Chinese officials from pouring resources into a quixotic plan to turn the city into a “cultural tourism destination” for wealthy Arabs. “To look the part, Yinchuan is undergoing an ambitious makeover. All of its street signs have been repainted to add Arabic translations and transliterations to the existing Chinese and English. Across from People’s Square in the city center stands an imposing convention center that has hosted the China-Arab States Expo, a biennial event that brings together businessmen and women from China and the Middle East. South of downtown, a $3.5 billion project to build a “World Muslim City” is slated to be completed in 2020. At Yinchuan Hedong International Airport, construction continues on a nearly 900,000-square-foot terminal to accommodate the anticipated surge in air traffic, including future direct flights from Amman and Kuala Lumpur. In May 2016, the Emirates airline inaugurated its new direct service from Dubai to Yinchuan. [Source: Kyle Haddad-Fonda, Foreign Policy, May 11, 2016]

Web Sites: Travel China Guide Travel China Guide ; Maps of Yinchuan: chinamaps.org ; Budget Accommodation: Check Lonely Planet books;

Getting There: Yinchuan is accessible by air and bus and lies on the main east-west train line between Beijing and Urumqi. At present, only five or so regular trains run between Beijing and Yinchuan each way each day, taking 11 to 20.5 hours. The running distance is 1,174 – 1, 335 kilometers (730 – 830 miles). Fast speed trains are expected to operating by the end of 2020, reducing the travel time to about five hours. Travel China Guide (click transportation) Travel China Guide

Sights in Yinchuan

Nanguan Mosque is one of the main tourist sight is Yinchuan. It was built around 400 years ago and restored in 1981 after being damaged in the Cultural Revolution. To enter the mosque you go through a wonderful green tiled archway. The mosque itself is composed of two levels, topped by three slightly onion-shaped blue domes, the largest of which sits in the middle and is 70 feet high. The upper level contains a prayer hall with enough room for 1000 people. The bottom level houses bathing halls and residences for the imams.

Haibao Pagoda (on the northern side of Yinchuan) is a strange, square-looking brick-and-stone structure that has 11 stories and reaches 160 feet into the air. If you feel adventurous there is a wooden ladder by which you can climb to the ninth floor. The ladder may or may not be open. Guesthouses can arrange camel rides through sand dunes and along the banks of the Yellow River.

Drum Tower is the oldest surviving observatory in China. Built during the mid-Southern Song Dynasty (960-1279) (A.D. 1127 to 1279) and formally known as the Yuanzhou Astronomical Clock Tower, it consists of an 18-foot-high masonry platform with a 43-foot. wood-frame structure. It contained a sophisticated water clock, a compass, a device for calibrating the clock and horns for announcing the quarter hours.

According to Archeology magazine: "The passage of time was marked by the constant flow of water from a main reservoir through several tanks to a final container. Further calibration using the movement of celestial bodies, and compensation for temperature and humidity brought the accuracy of such clocks to 20 seconds error per day, precision unmatched until the advent of reliable mechanical clocks in the eighteenth-century Europe."

Chengtian Temple (Ningxia Museum) (southwestern corner of Xingqing District of Yinchuan) has a history of more than 930 years and is a famous shrine of Buddhism. Featuring an ancient, simple design, it has a pagoda with halls arranged in the front and behind of the pagoda. The Ningxia Museum in the temple displays the historical documents, Helan Mountain cliff paintings, and Hui folk customs.

Near Yinchuan

Zhenbeibu China West Film Studio (35 kilometers northwest of Yinchuan) sits on the site of two ancient fortresses, which were built during the Ming and Qing dynasties to defend against the invasions of the tribes from the north side of Helan Mountain. One of the three biggest film studios in China, Zhenbeibu China West Film Studio is located here and has often been used in films set in frontiers of places of desolation — the equivalent of Chinese Westerns. More that 140 movies and TV series have been filmed here..

Zhenbeibu China West Film Studio is also a place for tourism, entertainment, leisure, dining and shopping. There are exhibition halls, including a traditional culture of China hall, ancient furniture hall and unique poster hall. There are special service for visitors. If you want to be a part of your favorite movie, the film studio can make it come true. With its complete facilities, they can make a short video for you. Mayinghua recreational center has snacks, rooms, card games; and free guide service. Hours Open: 8:30 am - 5:30 pm (winter); 8:00am - 6:00 pm (summer). Admission: 60 Yuan. Getting There: By Bus: No.16 from the West Gate or No.303 from the South Gate to the site.

Shapotou (160 kilometers from Yinchuan on the main east-west train line and the Yellow River) boasts a camel riding farm and offers dune sledding in the dunes of the Tengger Desert. Website: Lonely Planet Lonely Planet

China Hui Culture Park

China Hui Culture Park (Yongning County, 15 kilometers south of Yinchuan) is a sort of theme park revolving around the Hui ethnic minority. It is described as being the only place in China that displays ethnic Hui culture, religion, and traditions. The display includes Hui folk culture, religion, dances, songs and movies, food, commerce and agriculture.

The Hui culture is an integration of Islamic culture and traditional Chinese culture and originated in the Tang Dynasty (618-906). The construction of the park began in 2001 and opened to the public in 2005. The entire park covers an area of 1000 mu (66.7 hectares). The 300 mu (20 hectares) culture park includes an ethnic Hui museum, a ritual palace, a Hui ethnic customs village, a Hui catering and performance center, a Muslim restaurant, and an arts and craft shopping street that showcases the culture, history, songs and dances as well as traditions and customs of the Hui. The main attraction of the park is a white Islamic style building, which is surrounded by a long and round corridor. The Hui Museum in China has a total area of 7,000 square meters and looks like the Chinese character "Hui". It comprises five halls and has 1,000 relics and books on the Hui people and Islam.

Kyle Haddad-Fonda wrote in Foreign Policy: China Hui Culture Park celebrates the history and culture of China’s largest Muslim ethnicity, the Hui.“According to Ningxia’s tourism bureau, the China Hui Culture Park is a “Sino-Arab cultural bridge” that can “promote all aspects of Sino-Arab exchange and cooperation.” The park achieves a monumental scale, with its sparkling edifices designed to evoke India’s Taj Mahal and Turkey’s Blue Mosque.

“In the United States, a theme park that puts the culture of a marginalized and misunderstood religious group on public display, dramatizing that group’s history through dance routines performed by minority women in elaborate costumes and encouraging tourists to dress their children in traditional outfits purchased from the gift shop, might be regarded with some skepticism. In China, by contrast, the Hui Culture Park is heralded as an “AAAA national tourist site.”

Visiting China Hui Culture Park

Kyle Haddad-Fonda wrote in Foreign Policy: “Twelve miles south of Yinchuan along the Beijing-Tibet Expressway, the onion domes of the Hui Culture Park rise abruptly from the dusty plains of Yongning County. The front gate, framed by an intricate façade of plaster molded into Arabic calligraphy, stands an imposing 125 feet high. Designed to resemble the Taj Mahal, the gate — in the words of regional promotional materials — administers a “visual assault” that can “shake your internal spirit.” Yet while the structure was indeed imposing, on the day I visited the park in August the gate was open only enough to accommodate a single-file line. [Source: Kyle Haddad-Fonda, Foreign Policy, May 11, 2016]

“A handmade cardboard sign above the lone operational ticket window declared that the admission price had been temporarily discounted from about $12.25 to $9.20. “Construction,” explained the ticket seller succinctly as I gestured toward it. There is always construction at the Hui Culture Park. Since the park opened to the public in 2005, Ningxia’s authorities have pressed forward with their plan to turn it into a global tourist destination. Behind chain-link fences, work is underway on the second of a three-phase master plan that calls for the completed park to occupy nearly 165 acres. This year, workers also closed the park’s main museum of Hui artifacts, housed in a building shaped like the Chinese character for “Hui,” for an extensive renovation, even though the original structure is only a decade old.

“With both the main museum and the central reflecting pool out of commission, visitors were shunted down a narrow walkway, past a halal restaurant, and toward a temporary exhibit inside the Aisha Palace, a plain structure that struggles to live up to its grandiose name. Inside, female Hui tour guides took turns explaining their community’s history to clusters of Han tourists. The ethereal effect of the tour guides’ uniforms — floor-length blue and white sequined dresses and blue headdresses with flowing trains to cover their hair — was marred by the conspicuous pink battery packs that powered their microphones. Behind each guide, a gaggle of Han tourists in shorts and sun hats listened halfheartedly to their lectures on the spread of Islam.

“Unusual for a museum in modern China, the captions on the photographs inside the Aisha Palace were not rendered in English. Aside from plaques in Arabic that proclaimed the theme of each room in the complex, all the text in the museum was written in Chinese. Two of the four Arabic inscriptions bore scribbles in permanent marker, where misspellings in the original text had been quietly corrected. Since I was, on this day, the only visitor to the Hui Culture Park who was not part of a Chinese-speaking tour group, these blemishes went largely unnoticed.

“A curator of a museum of the Hui experience is faced with a difficult task. He or she must convey that Chinese Muslims have always been linked to the wider Islamic world, while still demonstrating that their primary loyalties are to the Chinese nation. The exhibits must reinforce that the Hui have always been integrated into Chinese society, while giving the impression that the Chinese Communist Party has done more to advance their status than did previous regimes. The result is an eclectic and uneven display. The museum celebrates the “enthusiastic participation” of the Hui in Sun Yat-sen’s plans to build a new China and lauds a Hui politician named Liu Geping for his early support of the Communist Party. The exhibit does not, however, include a single mention of the 1960s or 1970s, when the Cultural Revolution disrupted Chinese society and the country’s Muslims faced persecution. Instead, it skips forward two decades to present a photographic collage of Hui officials greeting visiting statesmen from the Middle East in the 1980s and beyond.

“Four bored Hui attendants, all in their early 20s, stood by the entrance taking tickets. Occasionally, one of the girls would rush over to the rack to help an adventurous Han woman into an abaya. Mostly, the four just chatted softly with one another. They were thrilled to see a Westerner — I was the only one that day, they told me — and eager to ply me with questions about who I was and why I was there. When I explained that I was an American who had come to Yinchuan to look around, one of the boys ventured to ask whether I was a Muslim. “I am not,” I answered, and he looked disappointed, so I offered that I could speak Arabic.

“This revelation was met with considerable excitement. All four of the attendants were able to speak at least a few words. One of the boys was quite adept. Switching to Arabic, he told me that he had spent two years studying in Khartoum. He described the Sudanese capital wistfully, and it was obvious that the opportunity to study in the Middle East had meant a great deal to him.“Do you get a lot of Arab tourists here?” I asked. He nodded. “But I don’t see any here today,” I challenged. “Everybody is Chinese.” “He sighed. “There might be more in September,” he said without conviction.

China Hui Culture Park Shows

Kyle Haddad-Fonda wrote in Foreign Policy: “In front of the museum, an army of workers was gathered around the central reflecting pool, which had been drained of its water. They were, I soon learned, installing the infrastructure that would support an elaborate nighttime pageant inspired by Middle Eastern folklore. Titled “A Dream Back into Tales from The Thousand and One Nights” and featuring a laser show with over 100 cast members, it debuted in September 2015. Taking advantage of the fact that Aladdin, according to legend, was born in China, it invites visitors to see connections between Chinese and Arab culture while enjoying the dazzling spectacle.

“To create this extravaganza, the Hui Culture Park’s backers spared no expense. They hired a producer of China Central Television’s annual spring gala to oversee the project, engaged a professor from Beijing’s Central Academy of Drama to design the choreography and lighting for the dance routines, and commissioned a celebrated magazine editor to write the script. From the outset, organizers trumpeted their willingness to lavish 200 million yuan, or about $30.6 million, on the production.In Chinese publications, the performance is never mentioned without reference to this sum. Anyone who pored over the congratulatory news accounts of its conception and development would be justified in concluding that its de facto title is actually “A 200 Million-Yuan Dream Back into Tales from The Thousand and One Nights.” In the cynical economic logic of modern China, this figure is a powerful piece of propaganda. After all, who could criticize the government’s treatment of a minority population if a venture backed by that same government is willing to spend $30.6 million on a light show and dance performance in honor of their cultural heritage? “When I visited the Hui Culture Park in August, there was little hint of the elaborate production being installed

Instead “guests at the Hui Culture Park are ushered into a model “village” that purports to replicate the traditional living conditions of the Hui. Its houses double as gift shops, purveying all manner of foodstuffs and trinkets native to Yinchuan. By far the biggest sellers are cheap facsimiles of traditional headwear: knit white skullcaps for boys and flowing sequined veils for girls. While the children of Han tourists frolic through the village wearing their new hats, their parents relax by the concession stand watching folk dancers on a small stage.

“Glittering in the background behind the dancers is the focal point of the Hui Culture Park, the Golden Palace. The Golden Palace’s onion-shaped domes, flanked by four minarets, are clearly designed to resemble a mosque, but the park’s staff refers to it only as a “palace.” Visitors are required to remove their shoes, and women who desire an immersive Islamic experience can opt to be fitted with a makeshift abaya from a rack by the door. In the corner is a panel explaining how Muslims pray, but one gets the sense that no Muslim has ever actually prayed inside. Instead, the only thing happening during my visit was an animated contest to see which of three tourists could best photograph the tiled dome with a selfie stick. It was a sterile, empty building, and no tourist spent more than a few minutes inside before wandering back into the courtyard. (Below, a Hui woman attendant chants Arabic prayers from a book in the Golden Palace at the Hui Culture Park on a slow day in the park.)

First Hui Street of China

Kyle Haddad-Fonda wrote in Foreign Policy: “Exiting back through the main gate of the Hui Culture Park, I trudged across the vast parking lot, desolate except for a few tour buses. Two local children on bicycles sped past the construction wall, not so much as glancing at the colorful advertisements that heralded Ningxia’s other AAAA national tourist sites. A lone driver at the cab stand honked at me to offer a ride back downtown, but I ignored him and kept walking. My ticket promised admission to the “First Hui Street of China,” and I was determined to get my money’s worth. [Source: Kyle Haddad-Fonda, Foreign Policy, May 11, 2016]

“In the recent past, the street housed 179 shops and restaurants offering traditional handicrafts, tourist gifts, and halal meals. For nearly a half mile, visitors could wander a maze of stone buildings and sample everything from pulled noodles to Arabic calligraphy. Today, however, the First Hui Street of China is abandoned.

“None of the stores is open for business, and only a few have any furniture at all. The colorful carved roofs of the stores are covered by a film of dust, and the paint on the red pillars of the elaborate front gate is beginning to peel. Bricks that have fallen out of the wall of the welcome pavilion lie in piles beneath the open windows, whose panes have been removed. Pedestrians must step over a pile of shattered green glass, cinder blocks, and discarded cigarette butts. Four faded red lanterns from a long-ago festival draw attention to the dangling threads where dozens more once hung.

“At the far end of the First Hui Street is the courtyard of the ornate Najiahu Mosque, which dates from the Qing Dynasty and can accommodate 1,000 worshippers. The Najiahu Mosque was built by members of the extended Na family, who moved to the area from Mongolia. In front of the mosque is a plaque that celebrates the renovation of the mosque in recent decades. The plaque, naturally, ignores the reason why reconstruction was necessary: During the Cultural Revolution, the mosque was shut down, and the complex was converted into a ball-bearing factory. While the main prayer hall survived unscathed, other parts of the structure were knocked to the ground. Throughout this period of political upheaval, descendants of the Na family were compelled to raise pigs on the surrounding farmland.

“Today, the reconstructed mosque does double duty as a functioning house of worship and a tourist attraction. Near the complex’s entrance is a classroom that serves both purposes. During my visit, I stood next to the classroom’s open window to listen to the young boys inside attempt to mimic their teacher’s recitation of Quranic verses as part of an elementary Arabic class, shouting each passage in unison at the top of their lungs. The boys’ passion reflected a frenzy of interest among Chinese Muslims in learning Arabic. According to official estimates, 3,000 students in Ningxia now study the language, including nearly 1,200 at the massive Tongxin Arabic Language School alone. As construction continues on dozens of projects designed to bring Yinchuan closer to the Arab world, the city’s Arabic mania can only intensify.

“After decades of discouraging religiosity in any form, the Chinese government is encouraging Muslims to feel kinship with the people of the Middle East. The residents of Yinchuan have embraced their special status with an ardor that extends beyond the control of the state machinery that created it. Chinese authorities may be able to manicure every inch of a theme park to express their chosen narrative, but channeling the enthusiasm of their citizens will prove a far greater challenge.

“It occurred to me as I listened that the boys in the Najiahu Mosque — reciting Arabic behind open windows at the heart of a tourist site that charges admission — were themselves on display. But at that moment, I did not care whether the scene was staged. Their excitement was the first sign of life I had seen that day.

Rock Carving on Helan Mountains

Helanshan Rock Carvings (40 kilometers and more from Yinchuan) are well known throughout the world and was the site a the International Rock Carvings Organization conference in 1991. In the hillsides of Helanshan (Mt. Helan), there are several thousand rock carvings by ancient nomadic tribes — the Helanshan Rock Carvings. Most of them are concentrated at Halankou Pass, which has more than 1000 carvings.

It is also a key site of relics being protected by the state. It is readily accessible by various traffic means. Of all the cavings, a great number are images of human faces, handprints, and hunting, and offering sacrifice. Among the animal paintings, there are running deer, blue sheep, tigers and leopards, duckbills, and flying birds.

According to the textual research by specialists, these rock carvings can be dating back to 6000 years before the dynasties og Ming and Qing. It was an art gallery created by ancient nomadic tribes. The artistic style of these rock carvings is wild and dense and thick, in simple design conceiving a unique artistic conception and value. They provide valuable materials for the study of the ways of life, ideas of religion, and war, farming and husbandry, hunting, and astronomy of various ethnic minority groups in ancient China.

Shahu Lake Area

Shahu Lake (56 kilometers northwest of Yinchuan) is welcome sight in a dry landscape. People and migrating birds congregate on a small island near the shore of the lake. Lake Shahu tourism area boasts sand in the south and water in the north, combines the landscapes of the water and mountains of South China with vast sandscapes and deserts of North China.

Shahu Lake is a haven of birds and fish. Tourists can watch all kinds of birds from the birdwatching tower. The lake is often attracts tens of thousands of birds such as white cranes, black storks and swans. In every spring, many birds come to lay their eggs. Birds feed on the small fish and bird waste nurture reeds and water grass and plankton that food for fish and birds. Among the species of fish found in the lake are common carps, silver carp, variegated carps and Wuchang fish. Giant salamanders and giant soft-shelled turtles also inhabit the lake.

Restaurants around the lake specialize in fish banquets. Freshly-captured variegated carp weighing around 15 kilograms, skillfully cooked, are offered to visitors. Tourists can go fishing if they so choose. A vast desert covering an area of 30000 mu of land lies in the south of the lake. Tourist boats and motorboats are provided and tourists. Swimming in the lake is allowed. Camels rides are cable cars are available. Yurts are provided for tourists to sleep in at very low prices.

Western Xia Tombs

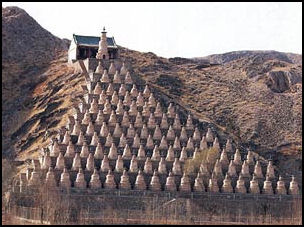

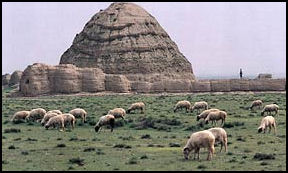

Western Xia Mausoleum (on the eastern slopes of the Helan Mountain 30 kilometers west of Yinchuan) contains the tombs of the emperors of western Xia. The site measures 10 kilometers (six miles) from north to south and five kilometers (three miles) from east to west. There are nine main burial mounds with emperors and 253 annex tombs scattered around the area. The largest mounds cover an area of 100,000 square meters. They have watch towers, sacred walls, stele pavilions and outer and inner ruined cities. Only one of the tumuli and four of the annex tombs have thus far been excavated.

There are huge architectural relics in the north and the ruins of ancient kilns in the east. Each tomb has an underground burial chamber, buildings and gardens. Based on the historical events of the Western Xia, 18 groups of artistic scenes and 160 figure statues in the Western Xia History Art Museum inside the Western Xia imperial cemetery represent the glorious civilization of the Western Xia Dynasty, recalling the years when the Dangxiang Clan expanded the frontiers of their country, abolishing slavery, reforming the civil system, and creating their writing characters.

Western Xia Imperial Tombs was nominated to be a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2013. According to a report submitted to UNESCO: Western Xia Imperial Tombs are the royal mausoleums of the emperors in the Western Xia Dynasty (1038-1227). Located at the eastern slope of the Helan Mountains, western suburb,they are the best-preserved historic cultural heritage representing the Tangut civilization at the largest scale and in the highest rank. Built between the 11th and 13th centuries, the Tombs are connected with the Helan Mountains in the west and with the Yinchuan Plain and the Yellow River in the east. They are situated in a spacious land higher in the west than the east. Occupying an area of some 50 square kilometers, the Western Xia Imperial Tombs include 9 imperial mausoleums, 254 subordinate tombs, 1 site of large architectural complex and more than 10 brick-and-tile kiln sites. The imperial mausoleums are lined up along the eastern slope of the Helan Mountains from north to south. The whole grand burial complex extends like a long and narrow south-north ribbon. [Source: National Commission of the People's Republic of China for UNESCO]

“Set in the vast Gobi desert in front of the rolling Helan Mountains, the Tombs narrates the unique historical atmosphere and ethnic features of the Western Xia Dynasty by the magnificent layout, tiered tomb walls, high towers and various mausoleum buildings. Many unearthed funerary objects and the remaining cultural relics such as inscriptions, stone statues and building components take on vivid shapes, unique ornamentations, and living nomadic features.

The Western Xia Imperial Tombs remain as ruins since the fall of Western Xia Dynasty in 1227. People can clearly see the location and layout of the burial complex. A variety of cultural relics have been well-preserved, including the tomb walls, tomb platforms, foundations and building components. The burial ways, construction techniques and arts of the Tombs truly reflect the unique values of Tangut civilization in widely learning from others and advocating cultural fusion. The Western Xia Imperial Tombs They bear testimony to the unique heritage values of the Tangut civilization. Various mausoleum sites in large numbers reflect the immense scale and high rank, various composition and exquisite craftsmanship of the Western Xia Imperial Tombs, representing the well-developed and distinctive Tangut civilization. “

Admission: 60 yuan; Tel: +86-0951-6119581 Getting There: You can take a tourist bus from Yinchuan tourist bus station. Buses depart at 8:30 and 9:30 every day; the ticket price is nine yuan per person. You can also take No. 1 bus from Yinchuan Xinyue Square, 8 yuan per person.

Western Xia Civilization

Western Xia Dynasty (1038-1227) was a feudal dynasty ruled by the Dangxiang Clan of the Tangut tribe that ruled over present-day Ningxia and Gansu. It lasted for some 190 years under ten emperors. The Tangut tribe was related to Tibetans and established the Western Xia Dynasty on the outskirts of the Song Dynasty (960-1279). The Western Xia Dynasty was an extension of the ancient kingdom of the Tangut people, whose capital was captured by Genghis Khan in the early 13th century.

According to a report submitted to UNESCO: The Tangut civilization, an ethnic minority civilization, prospering in an agricultural-husbandry area in Northwest China, shows its excellent adaptability and outstanding cultural diversity. The general layout of the Tombs imitates the imperial mausoleum construction of the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1279). In terms of site selection, layout, burial ways, building techniques and arts, the builders not only learned the experience from the ritual system and cultural achievements of the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1279) but also combined their own ethnic customs such as mountain worship, belief in necromancy and aesthetic orientations, reflecting the strong characteristics of the Tangut civilization’s inclusiveness and cultural fusion. As the site of the large tomb group for the Western Xia emperors, the Tombs bear special witness to the long vanished Tangut civilization. [Source: National Commission of the People's Republic of China for UNESCO]

“Tangut civilization was created by the Tangut people, an ethnic minority group, and prospered in an agricultural-husbandry area in Northwest China between the 11th and 13th centuries. Occupying a special position in the Chinese history, the West Xia civilization made great contributions to China’s diverse culture. From the early 9th century to the 14th century, many northern-Chinese tribes rose in the endless disputes and accelerated the process of the feudalism under the influence of the Han culture. They ruled over all or part of China.

“The Khitan people founded “Liao” (916-1125) and built the imperial mausoleum–the Liao Tombs. The Tangut people founded “Western Xia” (1038-1227) and built the Western Xia Imperial Tombs. The Jurchen people founded “Jin” (1115-1234) and built the Jin Tombs. The Qochu (Qara-hoja in Uygur) and Tubo people also left the tombs of their kings. These ethnic minorities in northern China are closely related to the Han culture due to the geographical proximity, military conflict and cultural penetration. Their mausoleum systems not only drew upon experience from the Han culture but also maintained their own traditional ethnic cultures.

“By comparison, the Western Xia Imperial Tombs and other counterparts in the same period, all took reference from the mausoleum systems since the Tang and Song dynasties and meanwhile showcased their own ethnic features and cultural connotations. The Western Xia Imperial Tombs prove to be a unique mixture blended by the Song mausoleum system, traditional Tangut culture and Buddhist culture. They are unique in inheritance, funeral customs, layout and architectural design. Compared with the tombs of Liao, Jin, Uighur and other nomads, the Western Xia Imperial Tombs bear witness to the civilization of different nations and take a special position in China’s ancient mausoleum system due to the huge size and the preserved state.

“According to New Chronicle of Ningxia in Emperor Jiajing’s Reign of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), “Lying east of the Helan Mountains are the imperial tombs of Western Xia modeled after the Song tombs”. The Western Xia Imperial Tombs and Song Tombs in Gong County are ancient imperial mausoleums built roughly at the same period. The Tangut people of the Western Xia Empire had close ties with the Song People in economic, political, cultural and other sectors. The Western Xia emperors identified and adopted the Song culture, which could explain many similarities between Western Xia Imperial Tombs and Song Tombs in Gong County. Yet the Western Xia Imperial Tombs show a remarkable distinction from the Song Tombs in Gong County due to the unique lifestyle, religious belief and funeral customs in the Western Xia Regime. The main differences lie in the heritage values and timelines, especially in mausoleum system and funeral customs. The Song Tombs in Gong County demonstrate typical funeral customs and cultural inheritance from the Han Chinese, while the Western Xia Imperial Tombs show the unique lifestyle, religious thoughts and values orientation of the Tangut people under the influence of the Han culture and, attesting the cultural exchanges among nations in northwest China.

“The Western Xia Empire existed for nearly two centuries before the conquest by the Mongols. Most of the empire’s cultural heritages have vanished. Among the few surviving Western Xia historical remains there are some 10 burial sites, more than 10 city sites including the Black City, Buddhist temples, pagodas, cave temples, detached royal palaces and gardens.”

Great Wall of China in Ningxia

Great Wall of China in Ningxia can be seen all over Ningxia, but mostly in the mountains of Guyuan north of Yinchuan. The Great Wall was built there during many periods of history, during: Warring States Period: (453-221 B.C.), the Qin Dynasty (221-207 B.C.), the Han Dynasty: (206 B.C. to A.D. 220), the Sui Dynasty (581–618), Jin Period (A.D. 265-420) and Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). The total recorded length of the Great Wall in Ningxia is 1,507 kilometers (668 miles), with 517.9 kilometers (355 miles) of still visible wall, 589 watch towers, 237 beacon towers, and 25 forts. The wall rangies from one to three meters (3–10 feet) in height with flanking towers protruding from the wall about every 200 to 300 meters or so. Beacon towers, barracks, and forts were also built at the important passes and mountain tops. [Source: China Highlights

Reporting the Great Wall in Ningxia, Brook Larmer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: n a barren desert hilltop, a local shepherd, Ding Shangyi, and I gaze out at a scene of austere beauty. The ocher-colored wall below us, constructed of tamped earth instead of stone, lacks the undulations and crenelations that define the eastern sections. But here, a simpler wall curves along the western flank of the Helan Mountains, extending across a rocky moonscape to the far horizon. For the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), this was the frontier, the end of the world — and it still feels that way. [Source: Brook Larmer, Smithsonian Magazine, August 2008]

“Ding, 52, lives alone in the shadow of the wall near Sanguankou Pass. He corrals his 700 sheep at night in a pen that abuts the 30-foot-tall barrier. Centuries of erosion have rounded the wall's edges and pockmarked its sides, making it seem less a monumental achievement than a kind of giant sponge laid across gravelly terrain. Although Ding has no idea of the wall's age — "a hundred years old," Ding guesses, off by about three and a half centuries — he reckons correctly that it was meant to "repel the Mongols."

Great Wall of the State of the Qin is the oldest section of Great Wall in Ningxia Province. About 200 kilometers (120 miles) long, it was built in the Warring States Period (475–221 B.C.). A large part of it was built under Emperor Zhaoxiang (325-251 B.C.) of the state of Qin and still remains now, making it one of the oldest existing parts of the Great Wall. This wall was renovated and extended during the Qin (221–206 BC) and Han (206 B.C. – A.D. 220) dynasties, and was fully restored during the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). The Qin Dynasty renovated the Great Wall in the Guyuan area. The wall was extended northward and westward by the army stationed on the Great Wall using the Yellow River.

Han and Sui Dynasty Great Wall initially consisted of the Great Wall built by its predecessor to defend against horsemen to the north. During the the reign of Emperor Wudi (156-87 BC) the Han Empire grew and the Great Wall was built to reflect thus, stretching far into northern Ningxia. Emperor Wendi of the Sui Dynasty (581–618) ordered widespread building of the Great Wall, to defend borders against invaders from the north, soon after his succeeding to the throne in 581. His main contribution was the 90-kilometer (56-mile) Great Wall section along the eastern border of today's Ningxia.

Ming-Era Great Wall of China in Ningxia

Ming Dynasty Great Wall is also known as the border wall. Built in the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), it is composed of four sections: 1) the 400-kilometer West Great Wall, between Jingyuan County in Gansu and Helan Mountain in the north of Zhongwei Prefecture, Ningxia; 2) the North Great Wall, divided into three sections: the Old North Great Wall Section, the Helan Mountain to Yellow River West Bank Section, and the Long Embankment Section in Taole County; 3) the East Great Wall, The East Great Wall starts at Hengcheng in Lingwu County, running east through Yanchi County, and ending in Dingbian County in Shaanxi Province; and 4) the Guyuan Inner Great Wall, built on the very site of the Qin-era Great Wall, stretching west-east for about 200 km from Xiji County to Pengyang County.

According to China Highlights: The well-preserved main body of the North Great Wall section in Hongguozi Town, is 5.8 km (3.6 miles) long. 3.7 km (2.3 miles) of which is rammed soil on the plains, and 2.1 km (1.3 miles) of which is of stone in the mountains. The Helan Mountain (Zao'ergou ) to Yellow River West Bank Section was built in the 10th year of the Emperor Jiajing's reign (1531). This section served as north pass gateway. It was 20 kilometers (12 miles) long, but only a few damaged soil walls remain today due to desert erosion. The Long Embankment Section follows the Yellow River south to Pingluo County, where it joins the East Great Wall. The Yellow River's Ningxia-side levees served as the Great Wall, hence it was called the Long Embankment.

“The East Great Wall was built in two parts: the Hedong Wall and the Hengcheng–Huamachi Wall.The first part, built in the 10th year of Emperor Chenghua (1474), was the Hedong Wall (the 'River East Wall'). 193 km (120 miles) long, numerous " "-shaped deep ditches were dug outside for defense. It was rebuilt in the 10th year of Emperor Jiajing (1531) as it had suffered great damage. The second part, 180 km (112 miles) long, started in Hengcheng Village in Lingwu County and ended at Huamachi in Yanchi County Town. It was seriously damaged in Xingwuying Village in Yanchi County, therefore a 53-km (33-mile) ditch was dug along each side of the wall during the 16th year of Emperor Jiajing's reign (1537).”

Great Wall in Ningxia Threatened by Desertification

Larmer wrote” “Nowhere are threats to the wall more evident than in Ningxia. The most relentless enemy is desertification—a scourge that began with construction of the Great Wall itself. Imperial policy decreed that grass and trees be torched within 60 miles of the wall, depriving enemies of the element of surprise. Inside the wall, the cleared land was used for crops to sustain soldiers. By the middle of the Ming dynasty, 2.8 million acres of forest had been converted to farmland. The result? "An environmental disaster," says Cheng. [Source: Brook Larmer, Smithsonian Magazine, August 2008]

“Today, with the added pressures of global warming, overgrazing and unwise agricultural policies, China's northern desert is expanding at an alarming rate, devouring approximately one million acres of grassland annually. The Great Wall stands in its path. Shifting sands may occasionally expose a long-buried section—as happened in Ningxia in 2002—but for the most part, they do far more harm than good. Rising dunes swallow entire stretches of wall; fierce desert winds shear off its top and sides like a sandblaster. Here, along the flanks of the Helan Mountains, water, ironically enough, is the greatest threat. Flash floods run off denuded highlands, gouging out the wall's base and causing upper levels to teeter and collapse.

Sandstorms in northwest China are blamed for reducing sections of the Great Wall of China to dust and dirt in remarkably short periods of time. The problem is particularly severe in Gansu Province where many sections are made of from mud and mud brick rather than brick and stone. One three mile section in Minqiin County in Gansu that was built in the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. to A.D. 220) is “rapidly disappearing” and may be gone in 20 years.

Construction and Pilfering Materials from the Great Wall of China

Brook Larmer wrote in Smithsonian Magazine: “ At Sanguankou Pass, two large gaps have been blasted through the wall, one for a highway linking Ningxia to Inner Mongolia—the wall here marks the border—and the other for a quarry operated by a state-owned gravel company. Trucks rumble through the breach every few minutes, picking up loads of rock destined to pave Ningxia's roads. Less than a mile away, wild horses lope along the wall, while Ding's sheep forage for roots on rocky hills. [Source: Brook Larmer, Smithsonian Magazine, August 2008]

“The plundering of the Great Wall, once fed by poverty, is now fueled by progress. In the early days of the People's Republic, in the 1950s, peasants pilfered tamped earth from the ramparts to replenish their fields, and stones to build houses. (I recently visited families in the Ningxia town of Yanchi who still live in caves dug out of the wall during the Cultural Revolution of 1966-76.) Two decades of economic growth have turned small-scale damage into major destruction. In Shizuishan, a heavily polluted industrial city along the Yellow River in northern Ningxia, the wall has collapsed because of erosion—even as the Great Wall Industrial Park thrives next door. Elsewhere in Ningxia, construction of a paper mill in Zhongwei and a petrochemical factory in Yanchi has destroyed sections of the wall.

“Regulations enacted in late 2006—focusing on protecting the Great Wall in its entirety—were intended to curb such abuses. Damaging the wall is now a criminal offense. Anyone caught bulldozing sections or conducting all-night raves on its ramparts—two of many indignities the wall has suffered—now faces fines. The laws, however, contain no provisions for extra personnel or funds. According to Dong Yaohui, president of the China Great Wall Society, "The problem is not lack of laws, but failure to put them into practice."

“Enforcement is especially difficult in Ningxia, where a vast, 900-mile-long network of walls is overseen by a cultural heritage bureau with only three employees. On a recent visit to the region, Cheng Dalin investigated several violations of the new regulations and recommended penalties against three companies that had blasted holes in the wall. But even if the fines were paid—and it's not clear that they were—his intervention came too late. The wall in those three areas had already been destroyed."

Xumishan Grottoes

Xumishan Grottoes (250 kilometers south of Yinchuan, 175 kilometers east of Lanzhou) were carved out of red sandstone cliffs and decorated with Buddhist statues between the 5th and 10th centuries, with the work most likely done by local artisans and monks and funded by merchants and nobles. The 130 or caves are located mostly in eight clusters spread out over a 1.5-kilometer-long area. Xumishan is a Chinese-language variation of “Mount Sumeru," the Sanskrit name of the holy Buddhist mountains at the center of the universe.

About half the grottoes have nothing in them. They are believed to have been used by monks for mediation or study. The others have wall paintings and statues, many with Indian and Central Asian influences. The biggest sculpture is a 20-meter-high Maitreya, Buddha of the Future. Other Maitreya can be found in other grottoes. Wind, sand and human occupation have taken their toll over the centuries. Only about 10 percent of the caves are in good condition. Restoration work by the Chinese relied heavily on concrete.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Nolls China Web site; CNTO; Perrochon photo site; Beifan.com; University of Washington; Ohio State University; UNESCO; Wikipedia; Julie Chao photo site

Text Sources: CNTO (China National Tourist Organization), China.org, UNESCO, reports submitted to UNESCO, Wikipedia, Lonely Planet guides, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, China Daily, Xinhua, Global Times, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Bloomberg, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Updated in September 2021