TRAVELING IN TIBET

Tibet is home spectacular snow-capped peaks, glaciers, wide rivers, highland lakes, geothermal springs, vast pastoral areas, magnificent monasteries, brilliant religious arts, and interesting ethnic groups. Among the most famous scenic spots and historic sites are Potala Palace in Lhasa, Mt. Everest, Drepung, Sear, and Tashlunbu monasteries, the Yalong River in southern Tibet, Mt. Kailash and the Tombs of the Tibetan Kings.

Tibet is home spectacular snow-capped peaks, glaciers, wide rivers, highland lakes, geothermal springs, vast pastoral areas, magnificent monasteries, brilliant religious arts, and interesting ethnic groups. Among the most famous scenic spots and historic sites are Potala Palace in Lhasa, Mt. Everest, Drepung, Sear, and Tashlunbu monasteries, the Yalong River in southern Tibet, Mt. Kailash and the Tombs of the Tibetan Kings.

Tourism has boomed in Tibet since the 1980s, About 6.85 million people visited Tibet in 2010, mostly Chinese but also people from all over: Korea, Europe, Japan, the U.S., India, Southeast Asia. The only way for non-Chinese to enter Tibet these days is to do so with the help of a travel agency that secures all the necessary permits to travel in the region. This system — more or less permanently put in place after the Tibetan riots in 2008 — allows the Chinese government to control foreigners traveling around within Tibet and offers money-making opportunities for the handful of travel agencies that conduct tours there. Despite this apparent Beijing-endorsed cartel, some of the tours are remarkably inexpensive and for the most part well organized and interesting — as long as you are willing to throw yourself at the mercy of backpacker social life and the obstacles that the Chinese government throws up.

Before the new train was opened the overland journey to Tibet took days, even weeks, and involved either traversing long stretches of the Tibetan plateau or switchbacking up and down dozens of mountain passes. There is a road connecting Nepal with China but usually you have to be part of an organized tour to travel on it. The roads and passes between Tibet and India, Bhutan and Myanmar and in the border areas are generally only open to military vehicles.

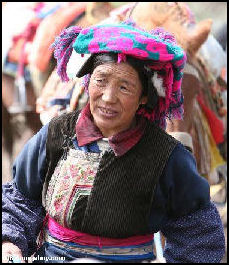

Tibet is definitely an amazing place. The thin air buzz, low clouds and deep blue sky make up for the lack of oxygen, general brownness and bleakness of the landscape and the lip-cracking harshness of the high-altitude sun. the Tibetans themselves are something to behold. The ways they dress, wear their hair, keep warm, carry their children and go about their religious activities seems about as far removed from work-driven and success-oriented Western — and Chinese — life as you can get.

Tourists in organized tours usually stay in Chinese Government hotels and are transported in minibuses or Toyota Landcruisers — depending on the terrain — which sometimes get stuck in mud or sand or breakdown because of the high altitude and have to be restarted again after fluid is sucked from the engine with a tube. The highest passes are over 5,500 meters (17,000 feet). Parts of the road can be washed out on the June-to-September monsoon season.

Foreign travelers are generally not allowed to visit from mid-February through the end of March, over concerns of unrest at that time. The high season for Tibet is from April to October and November to early February is the low season.

Lhasa-Everest Trip

I traveled to Lhasa, Shigatse (Tibet’s second largest city) and the Mt. Everest region of Tibet in December 2014-January 2015 as part of tour that originated in Shanghai and generally had a great time but found that trip was defined as much by the personalities of my travel mates — strangers mostly younger than me who I was thrown together with for almost the entire day, everyday, for six days of the US$1,400, 10-day tour — as by the sights and travel itself. But more on that later.

The Potala — the fortress palace of the Dalai Lama in Lhasa — is one of the most awesome buildings in the world, ranking up there with Angkor Wat, the Taj Mahal and Luxor Temple in Egypt. But what makes it even better is that it still alive with religious life, and is not just a tourist sight. Everyday, almost around the clock, masses of Tibetans circle it clockwise in a Tibetan Buddhist religious ritual called a kora.

And Everest, it goes without saying, is one of the world’s premier natural sites. I have seen Everest from both the Chinese-Tibetan side and the Nepalese side and found the Chinese-Tibetan side offers more outstanding views of Everest itself and the Himalayan massif it is part of, which embraces four of the world’s top six highest peaks, but is not as fun to get to as you essentially drive to a parking lot in front of the 5,200-meter-high Everest Base Camp and look at Everest and hop back in your vehicle and drive out. By contrast, the view of Everest on the Nepalese side is equally impressive and quite different but comes as a reward for surviving an adventurous plane flight and making a five day trek to get to the 5,644-meter-high (18,519-foot-high) viewing spot.

What Foreign Tourists Need to Do to Visit Tibet

All foreign citizens need a Tibet Travel Permit to enter Tibet, and this can only be obtained by a registered tour operator. Once you have your Chinese Entry Visa, your tour operator will be able to book your itinerary, and apply for the Tibet Travel Permit. However, since Tibet has restrictions on foreign visitors traveling alone, they will also provide you with a guide for the entire trip. An Alien’s Travel Permit is necessary for traveling outside Lhasa. Those wishing to visit border areas or sensitive areas such as Mount Kailash and Lake Manasarovar need a military permit, which is obtained by your guide once you are in Lhasa.

Foreigners need to get the following ready before you start your trip to Tibet, according to Tibet Daily: 1) Applying for the Travel Permission: A foreigner needs to submit his/her travel period, route(s) to Tibet, travel purpose, name, passport number, occupation, work place, address and contact information to the Tibet Autonomous Regional Tourist Reception Agency via a local travel agency. He/she will go through the confirmation procedures in a short period. Usually, the confirmation letter will be delivered by express to a domestic location in seven days. [Source: Xinhua, January 11, 2010]

2) Certificates: Passport and Visa: A foreign tourist or mountaineer should bear a native passport and a visa issued by the Chinese Embassy stationed in his/her country, except that tourists from the countries that have signed visa-free agreements with China.

3) Confirmation Letter: Organized oversea travel groups should apply for the letter through the Tibet Autonomous Regional Tourist Reception Agency. Tourists can consult the tour offices of the Tibet Autonomous Regional Tourism Bureau in the places such as Beijing, Chengdu, Xi'an, Shanghai, Xining, Hong Kong SAR, and oversea offices in the countries like Nepal, the U.S. and Japan.

Organized Trip in Tibet

My trip to Tibet — organized by Tibettravel.org — encompassed six days in the Everest and Lhasa region and two days to get to Lhasa from Shanghai, mostly by train, and two days to get back to Shanghai by train (flying back from Lhasa costs about US$600, compared to about US$200 for the train). There were some stumbles and hassles organizing the trip and getting it going but these were mainly the result of obstacles presented by the Chinese government and railway system — and tibettravel.org was very helpful in navigating through the rough spots.

My trip to Tibet — organized by Tibettravel.org — encompassed six days in the Everest and Lhasa region and two days to get to Lhasa from Shanghai, mostly by train, and two days to get back to Shanghai by train (flying back from Lhasa costs about US$600, compared to about US$200 for the train). There were some stumbles and hassles organizing the trip and getting it going but these were mainly the result of obstacles presented by the Chinese government and railway system — and tibettravel.org was very helpful in navigating through the rough spots.

Tibettravel.org’s main office is in Chengdu, China. From there, their travel agents help travelers organize their trip through e-mail, Skype or whatever. Their main duties are arranging the permits to enter Tibet and getting train and plane tickets for their customers. Once you are in Tibet, you are placed in the hands of their Lhasa-based Tibetan staff. Tibettravel.org requires a US$200 deposit to book the trip, with the balance paid in Lhasa. The permits are free. The visa for an American is around US$140.

In my case I had some trouble getting my Chinese visa and train tickets. To get a Chinese visa you generally need a hotel reservation and proof of a plane ticket when you apply at a Chinese embassy or consulate. I had a plane ticket printout and thought my travel company itinerary — which had hotels named on it — would serve in lieu of the hotel reservation but that was not the case.The people at the China consulate I dealt with were especially suspicious of travel to Tibet. A agent at Tibetravel.org gave me the tip of making a hotel reservation through a site called Ctrip for a hotel in Shanghai — not Tibet — and then cancelling the reservation. I did this and e-mailed my hotel reservation to the Chinese consulate and was able to get my visa without making a second trip. Double check the visa policy at the place where you get your visa, because the policies often vary from consulate to consulate.

Getting to Tibet

Currently there are three options for travel to Tibet, by plane, by road and by train:.

1) Taking the plane is a comfortable and timesaving option, but offers little time for you to acclimatise to the altitude; this may cause sickness. On flights between Lhasa and Kathmandu, pilots often swing by Everest to give them an eye-level view of the world's highest mountain.

2) Taking the bus along one of five highways that have been opened-up for tourists' use. This will take longer but will enable you to see the amazing scenery en route. Furthermore, taking extra time allows for a more gradual acclimatization to the altitude.

3) Taking the train, is a fabulous new option, giving the opportunity to see hitherto unseen mountain scenery. With the operation of Tibet Railway from July 1st, 2006, more and more tourist have swarmed into Tibet via the great Tibet train.'

My trip began in Shanghai and one of the main objectives of the trip was to take the relatively new train to Lhasa (it was launched in 2007). Because I wanted to get acclimated to the altitude (Lhasa is 3,500 meters, 11,500 feet, high) and was traveling both to and from Lhasa by train, I decided to fly into the Chinese city of Xining, which is roughly at the midpoint of the two-day train trip to Lhasa and is 2,200 meters (7,218 feet) high. My plan was to visit some sights around Xining — such as the Dalai Lama’s birthplace, which is usually off limits to foreign tourists — while I adjusted to the altitude, but in the end I spent much of my time chasing down my train ticket to Lhasa.

When you book the Lhasa train — which your travel company does for you, paying for the ticket — you are given a ticket number which you show at the train station with your passport and travel permits to pick up the ticket. Generally, the tickets are purchased 20 days before the trip begins but in my case the ticket couldn’t be booked until the last minute and I didn’t get my ticket number until I was in Xining. For various reasons I had trouble getting the ticket and wasn’t able to visit the Xining sights I had hoped to see.

Anyway I got on the train to Lhasa in one piece and was happy about that as the trip to Lhasa and Mt. Everest was the heart of the trip. On the train were some members of my travel group, who began their journey in Beijing. They were Australians and Americans and already were quite buddy-buddy by the time I got on the train. They were friendly enough and I talked with them some, but had a hard time really penetrating the group and spent most of my time in my own compartment enjoying the scenery and doing some computer work. The train had electric outlets and it seemed as if everybody — foreigners, Chinese and Tibetans alike — had a smart phone, tablet or laptop — and wanted to charge up their devices with the outlets. I had a sleeping berth in a hard sleeper, a category of Chinese train service in which six people share a compartment with two sets of three-level bunk beds. In the past when I traveled in China I opted for the more comfortable four-person soft sleeper, but on the Lhasa trip, the hard sleeper wasn’t bad and was considerably cheaper than the soft sleeper. Insist on getting a lower berth. The top berths, especially, are hard to get to and not fit for doing much other than sleeping. All the berths come their own oxygen supply, for those that have trouble with the altitude.

Travel Tips for Tibet

Packing light is not the best thing to do in Tibet. It can get very cold at night, even in summer, so warm clothes are essential. You need good, warm layers, a decent down jacket, weatherproof pants, and sturdy boots. Sunglasses are necessary if you are adventuring in the mountains as there is a risk of snow blindness Unless you are trekking, a large backpack is not needed and not recommended, but a small one can be useful for day excursions to carry extra layers and essential items. Do not forget to bring all your any medications from home as getting hold of medicines my be difficult especially in remote areas.

Generally the period from April to October is the best time to visit Tibet. Since Lhasa is located at such a high altitude it is wise to be prepared before starting your journey. Due to the large temperature differences during any given day, one should be prepared to put on and take off clothes as the temperatures dictate and have a backpack to put them in. Because Tibet receives a great deal of sunshine, sunglasses, sunscreen, and a sun hat are indispensable items. When walking around in rural areas, it is good idea to carry a rock or stick to beat of the fierce Tibetan mastiff that guard many homes, flocks and herds.

Late August and Early September is the best time to visit eastern Tibet. The rainy season is June through August. Bus run in the area year-round but the roads are sometimes closed by snow or landslides. Sleeper buses (with bunks, not seats) and newer more comfortable buses leave from Xinnanmen bus station in Chengdu. The eight-hour trip from Chengdu to Kandling cost about US$15.

Please bear in mind that traveling in Lhasa, as well as in Tibet on the whole, is more challenging than other part of China. The roadside public toilets, for example, can be atrocious. I saw some pretty nasty car accidents in which it looked like people were killed. Many drivers of tourist vehicle take long, seemingly unnecessary breaks that take up a lot of time and extend the time spent on the road. At least in part this because the Chinese method of deterring speeders is recording your time at a police checkpoint so that when you stop at the next checkpoint, say, 70 kilometers down the road your time has to be over a certain limit. If it is under the limit that means you’ve been driving over the speed limit. In practice what happens is that the driver drives fast as usual and then stops somewhere to kill time.

Road Travel in Tibet

Most of the roads in Tibet are gravel and dirt, and many of them can only be traversed with a four-wheel-drive vehicle. Vehicles for long distance trips are often hired in pairs so one vehicle can help the other if there is a problem. They coast around US$1,000 a week. Guides and vehicles can be arranged for a cheaper price in Lhasa than outside it. Some backbackers used to hitchhike. Drivers usually expected to be paid. The mail trucks were preferable. A long trip costs around US$20.

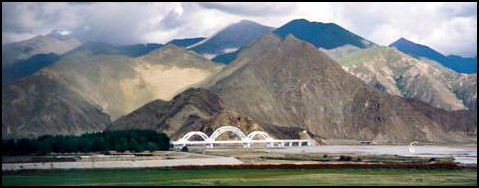

According to ASIRT: Efforts to upgrade and expand the road network are ongoing. Major roads linking Tibet with mainland China and other countries have been upgraded: 1) Sichuan-Tibet Highway (Chengdu to Lhasa); 2) Qinghai-Tibet Highway (Xining-Ge'ermu-Lhasa).; 3) Xinjinag-Tibet Highway (Yecheng-Burang); 4) Yunnan-Tibet Highway (Xiaguan-Makam) All townships and most villages have access to main road network. Road improvements reduced travel times from villages to main cities from days to a few hours. [Source: Association for Safe International Road Travel (ASIRT), 2011]

“Roads linking main cities and many roads to tourist destinations near Lhasa have been paved. Roads in remote areas are often unpaved, potholed and in poor condition, dusty in dry season and often impassible in rainy season, except by 4WD vehicles. Many roads and cities are affected by landslides, falling rocks, debris flows, avalanches and earthquakes. Region is subject to many natural disasters. Roads and bridges are often damaged; may temporarily close. Cities most commonly affected: Lhasa, Shigatse, Linzhi, and Zedang. Roads most often affected: Sichuan-Tibet Highway, Tanu-Dongjiu section; Sino-Nepal Highway, sections near Karu, Resa, Zhangmu and ZhangTsangpo. Snow avalanches commonly cause temporary closures of the Sino-Nepal Highway from Nyalam to Zhangmu. Most Common from October to April.”

Sichuan-Tibet Highway

Sichuan-Tibet Highway is one of the world's highest, most dangerous and roughest roads. Built between 1950 and 1954, it consists of two main branches — the 2412-kilometer northern route and the 2140-kilometer southern route — that branch off from the main road west of Chengdu past Luding and Kangding. The road has constantly been improved is less rough and dangerous than it used to be.

Most of the routes are comprised of twisting one lane dirt or gravel roads. Covering the distance between Chengdu and Lhasa used to take take two weeks to traverse by truck. Half the vehicles in the military convoys that traveled this route were fuel trucks that kept the other vehicles going. The Lonely Planet guides described an accident in which a truck overturned and one American lost half his arm and an Australian woman had multiple back injuries. It was several days before medical help arrived.

The Northern Branch of the Sichuan-Tibet Highway is 2412 kilometers long and branches off from the main road west of Chengdu past Luding and Kangding. Also known as Route 317, it passes over the 16,128-foot pass, Tro La, which is littered with the skeletons of vehicles that couldn't make it, and passes through the small Tibetan towns of Luhou, Graze and Dege (pronounced DEHR-geh). Buses from Kangding to Dege leave on odd-numbered days. The 370-mile journey takes at least two days, with buses stopping overnight in either Garze or Luhou, . Also on odd-numbered days there are buses between Chengdu and Garze. This journey takes about a day and half and and costs US$24.

Southern Branch of the Sichuan-Tibet Highway is 2140 kilometers long and branches off from the main road west of Chengdu past Luding and Kangding. It passes through the small Tibetan towns Litang and Batang. Litang(in Kham) is situated in a treeless valley that is 4,680 meters (15,350 feet) high. It is home to around 54,000 people, 95 percent of them Tibetans. The number of Chinese is growing. They run many of the shops and restaurants. Large numbers of herding families are also moving to the town, happy to gain access to schools, electricity and jobs. The busy government-sanctioned monastery is home to 300 monks. It has 3,000 monks in the 1950s before it was shout down in 1959. It reopened in the 1980s. Website: Lonely Planet Lonely Planet

Accommodation and Food in Tibet

Accommodation is reasonably plentiful in Lhasa and is like that of any large city in China. Along the roads for foreign travelers with their guide are limited to tourist-based hotels and hostels. While there are many other lodges and truck-stops along the road, these generally off-limits to foreign tourists. The best hotels along the route are normally in the major towns and cities, with some smaller lodges and hostels designed for tourists. In the small towns and villages near tourist sights there is usually some kind of guest house accommodation where foreign travelers can stay. The costs tend to be much higher for foreigners tthan for Chinese or Tibetans.

In Lhasa you can find a wide range of restaurants, including some with Western and Indian dishes. Sichuan cooking is common as there are a lot of Sichuanese in Tibet. In eastern Tibet, food is a mixture of Tibetan dishes and local Sichuan cuisine, though you can also find some western dishes on the menus at the hotels and hostels that deal with foreigners. In the rest of Tibet, Tibetan food is most common. If you are not into either Tibetan or Sichuan cuisine, you should bring food with you, and stock up in Lhasa.

Some Tibetan guest houses and motels used by locals contain rooms with a few cots and an iron stove with buckets full of sheep pellets for fuel. Some have an outdoor latrine. Some don't even have that. When there are toilets they usually don't work. Guests sometimes use blow torches to cook meals in their rooms.

Cheap guesthouses off-the-beaten track in Tibet often resemble prisons. There is usually no running water and no electricity at night. The floors are damp; the sheets are smelly. For washing guests are given a pail of water. When there is electricity light comes from bare light bulbs which don't have switches to turn them off. The worst cheap hotels have human excrement and frozen vomit on the staircases from previous guests who thought is was too cold to go outside and use the toilet.

Trekkers and people traveling around in jeeps usually camp and sleep in tents or stay in guest houses and hotels that are basic but are used to dealing with foreigners and are able to cater to their needs in a basic way. Expensive hotels in Lhasa justify their US$200-a-night price tag because they have amenities like oxygen tanks for guests with altitude sickness.

Tibetan Railway

A 1,142-kilometer railway between and Lhasa and Golmund in Qinghai Province — which is connected to the national rail system — opened in July 2006. The highest railway in the world, it reaches an elevation of 5,072 meters, surpassing Peru's Lima-Huancayo line which reached 4,800 meters, and cost US$4.2 billion to make. Reducing the journey from Golmund to Lhasa from three days to 15 hours, it features specially-designed cars, pressurized like aircraft, with filtered, sealed windows to protect passengers from ultraviolet rays and oxygen supplies to prevent passengers from getting altitude sickness and help them with the thin air. Former Chinese Premier Zhu Rongji called it “an unprecedented project in the history of mankind."

The railroad has been on the drawing boards for some time. Mao ordered feasability studied in the 1950s but the plans to build it were scrubbed due to engineering problems, lack of money and unrest in Tibet. A new rail line reached Golmud, the gateway to Tibet in 1984, but was prevented from continuing further because of permafrost and extreme cold.

Construction began in 2001 after methods for tunneling through ice and laying track on permafrost were worked out. The first 120-kilometer leg was complected in 2003. Once the operation was in full gear track was laid at a rate of about one kilometer a day. The first cargo trains went into operation on a limited basis in 2004. The railway is now being extended to Shigatse. China plans to extend it to the border of Nepal by 2013

The railway was opened with great fanfare with a nationally-televised ceremony featuring Chinese President Hu Jintao cutting a giant red ribbon at Golmud. Musicians in traditional Chinese and Tibetan costumes banged drums and cymbals as the 16-car train pulled out. “This is a magnificent feat by the Chinese people, and also a miracle in world railway history," Hu said. Few Tibetans ride on the train. The ticket prices are too high for them.

See Separate Article TIBETAN TRAIN factsanddetails.com

Route of the Tibetan Train

The Tibetan line begins in Golmund, where the train from Beijing to Lhasa stops for 30 minutes. The journey from Beijing takes passengers from one of the most densely populated areas of the world to one of the most remote and lightly populated areas, passing through vast sweeps of farmland, rocky deserts and Himalayan foothills along the way.

After Golmud the train rises into the Kunlun mountains and rolls through treeless valleys with ravines and streams with chalky-colored water. Icy peaks are visible in the distance. The accent to the Tibetan plateau is undramatic. There are no switchbacks and steep climbs. The ascent is gentle and less scenic than the road On the Tibetan plateau the train passes through grasslands with nomadic horsemen, herds of yaks, small alpine lakes and ravines with snowcapped peaks in the distance. Many of the stations are empty and train rushes right past the,

Quite a lot of altitude is covered. People often suffer from altitude sickness. Oxygen is pumped into the cars after Golmud but even then many people straggle with the thin air. Most people feel a slight headache. Bags of potato chips pop open.

Much of the route follows the Tibetan-Qinghai Highway. This road is empty except for occasion military convoy and Tibetan traders hauling barley and meat in wheelbarrows. Tangulla Pass, the highest pont on the railway, is almost 1,000 feet higher than Mt. Blanc and higher than the altitude that light aircraft fly. It is not clear when the pass is actually passed.

Tanggula Pass is not only the highest railway pass in the world it is the home of the highest station in the world. To reach this height the train climbs steadily at a grade of one in 50. It crosses the pass at speeds up to 100 kph. Describing the approach to the 5,072-meter-high pass, Jane Macartney wrote in the Times of London: “As the train climbed towards the highest railway pass on Earth, funny things began to happen. Pens leaked. Air-tight bags of crisps and peanuts burst open. Laptops crashed and MP3 players stopped playing. Passengers began feeling sick and some reached for their oxygen masks. A few vomited."

From Lhasa I took the 50-hour train back to Shanghai. The leg between Lhasa and Xining was spectacular. What was a brown landscape on the way to Lhasa was being blanketed in snow — in sometimes blizzard conditions — on the way out. There were no foreigners on the train this time. I spent my time chewing on spicy turkey feet with my Chinese and Tibetan compartment mates and looking for chiru — and kind of Tibetan antelope — out the window, catching a few glimpses of them among the thousands of yaks and sheep that graze on the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau. The high point of the train is 5,072-meter-high (16,640 foot-high) Tanggula Pass, but it was hard to figure out where it was. Between Xining and Shanghai the scenery was not so exciting. The glacier-capped peaks, long vistas and yak-herder settlements were replaced by coal-fired power plants, gravel pits and dreary, smog-cloaked Chinese towns.

Altitude Sickness

Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS, altitude sickness) affects some people who visit Tibet. AMS causes fluid to form in the brain and lungs and kills by causing the brain to swell and hemorrhage inside the skull. Many people die of it every year, and there is no rhyme or reason to who it strikes (sometimes fat smokers are unaffected while athletes get sick). Describing altitude sickness, one mountain climber told the Washington Post, “You feel terrible, your head is pounding, your body failing, you can't think, you can't move. I was fit, but I couldn't lift my head on my shoulders." The effects of the low oxygen on body tissues are noticeable above 3,500 meet (11,480 feet) and marked above 5,000 meters (16,400 feet)." Symptoms include headaches, nausea, vomiting, lightheadedness, lassitude, breathlessness, anorexia, fatigue, insomnia, swelling of hands, feet, or face, and decreased urine output.

People with severe AMS have difficulty breathing with minimal activity, feel extremely tired, and have a dry cough. When the disease becomes more advanced the victims have bubbly breathing, cough up fluid or blood, feel confused and become bluish in color.

Above 12,000 feet a swelling of the brain called HACE (high altitude cerebral edema) may occur. The first symptom of this disease is a severe headache, hallucinations, stumbling walk, drowsiness and faulty judgement (which can make self-diagnosis difficult). Brain damage and death can occur quickly. As is true with AMS, the best treatment for a cerebral edema is to descend quickly.

AMS generally affects people who ascend too quickly at elevations above 8000 feet. Those who fly from sea level to a higher elevation should be especially careful. The general rule of thumb is to "climb high and sleep low" and ascend no more than 1000 to 1,500 feet a day and take every third day off. If you ascend more than that rest a day or two. Even if you are super fit that is no guarantee you won't have problems.

The only cure for AMS is to descend to a lower elevation. If you experience any of the aforementioned AMS symptoms, descend immediately, the more you don't want to the more imperative it is that reach you lower elevations, even if it is rainy night.

To prevent altitude sickness eat and drink a lot. Diamox tablets are often prescribed as a preventative measure. They generally only treat the symptoms of mild AMS put do nothing to prevent the condition. Many local people chew on raw garlic.

Dealing with the High Altitude in Tibet

Generally, if you arrive in Lhasa by train you acclimatize as the train gradually ascends to 3,656-meter-high Lhasa. I stopped in 2200-meter-high high Xining — about halfway between Beijing as well as Shanghai and Lhasa — for a couple days of acclimatization to be on the safe side. The people that have the most trouble are those that arrive in Lhasa or Tibet by plane from a place near sea level and suddenly find themselves at 3,700 meters.

Roseanne Gerin wrote in the Beijing Review: The first order of business for most travelers to China's Tibet Autonomous Region is what to do to prevent the onset of altitude sickness....My drug of choice was Acetazolamide, also known as Diamox. I took one 125-mg tablet twice a day in the morning and evening for four days-one day before my departure and during the first three days of the trip. The bottle contained several warning stickers: may impair ability to drive a motor vehicle; may cause drowsiness or dizziness; do not take aspirin or a product containing aspirin without the knowledge or consent of your physician; and avoid prolonged or excessive exposure to direct and/or artificial sunlight while taking this medicine-the last of which was very hard to do considering Tibet's intense sunshine. [Source: Roseanne Gerin, Beijing Review December 25, 2008]

“I sought additional advice from people who had traveled there in case the prescription medicine failed to do the job. I didn't want to take a chance on re-experiencing some of the high altitude effects that I had a year earlier on a trip to the mountainous area of west China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. During a few hours' stop for lunch and camel rides at Karakul Lake, a glacial lake that lies 3,600 meters above sea level near the Tajikistani border, I developed a serious pressure headache, had difficulty speaking and bit my tongue when I tried to talk.

“A Canadian acquaintance who had lived in Beijing for a few years and traveled far and wide in China suggested that I drink four liters of water a day in Tibet. She received this advice from an American mountain climber she met at the base of Mount Qomolangma (Everest) a few years back. The downside: "There was an awful lot of peeing in them there barley fields," she wrote to me in an e-mail from Toronto.

Upon arriving in Lhasa, our local guide, a 29-year-old Tibetan who went by the English name Jane, suggested avoiding all medications and canisters of oxygen, which she said worked well only for sudden elevations at short intervals. Instead, she recommended lots of water, plenty of rest and no activity on the first day. Unfortunately, the water-and-rest prescription failed to do the trick for most people in our group. Sara from the U.S. state of New Jersey became physically ill on the hour-long drive from the airport into Lhasa, more so from the strong heat and blinding sunlight. Her nausea lasted throughout the evening and continued the next day before gradually wearing off.

“Talk of altitude sickness symptoms and possible preventives was prevalent throughout most of the seven-day trip. Monique, originally from Montreal, had been advised by her Chinese work colleagues in Shanghai not to wash her hair to avoid altitude sickness. They had tried this when they traveled to Tibet on a four-day corporate team-building trip. Monique did not follow their advice and washed her hair on the second day. Jane added that some Chinese also avoid showering to avoid altitude sickness. But no one gave this equally questionable precaution a second thought.

“Our hotel in Lhasa thoughtfully provided plastic canisters of oxygen for 40 yuan (US$5.8) each in our rooms along with 40-yuan boxes of red tablets containing Tibetan rhodiola, a herb that grows in the region's mountains and is said to increase physical and mental stamina and boost the immune system. The box said it was best to take two capsules twice a day at the start of one's exposure to high altitudes. No one tried them, although an American from Texas took some similar-looking blue herbal pills that he bought from a Chinese pharmacy in Beijing. Nevertheless, he still had several days of headaches and queasiness.

“Some members of the group took no medicine at all. Di from Australia said she could not take Acetazolamide, because she was allergic to sulfa medications. As a result, she suffered from "altitude giddiness" during most of the trip. The altitude did affect my year-round sinus and allergy conditions. Despite taking an over-the-counter allergy medication and using a prescription nasal spray during the trip, my nose was stuffy most nights, and my nostrils were slightly bloody, especially in the morning. Yet, with the Acetazolamide I was able to avoid the other maladies my fellow travelers complained of-hangover-like headaches, heart palpitations, general nausea and a lack of appetite. Avoiding alcohol (except for a few glasses of beer), drinking a cup of ginseng tea in the evening and walking slower than usual when ascending high places on hillsides, such as Potala Palace in Lhasa and the Dzong Fortress in Gyangze, also helped. I also chewed peppermint chicklets to ward off a dry throat and an upset tummy.

“Jane said it was normal for visitors to become acclimated after three or four days once they suffered through all the headaches and nausea, and that by the time they left six or seven days later, they had no problems. And so it was with all of us as we boarded our planes back to Beijing and Shanghai.”

Visiting Tibet in the Winter

I couldn’t believe how warm it was when I visited Tibet in December and January. It was a little unreasonably warm when I was there but not much. In Lhasa, which has the same latitude as Florida, it was generally in the 50s F during the day, dropping into the 20s at night. I brought a huge backpack with polypropylene underwear, a thick, fishermen’s knit sweater and various kinds of gloves and glove covers I didn’t need in Lhasa. However, it was quite cold in the Everest area. There was not heat in my hotel room and I slept with my down jacket on and hot water bottles. At my hotel in Lhasa, there was plenty of heat from a radiator.

According to Trendy Traveler: “A traveler's primary concern is heating but it is no big deal for the locals. During the day, the bright sun keeps them warm and happy. At night, they burn dried yak dung in stoves, possibly the most environmentally friendly heating system in the world. Life in the capital, Lhasa, also fires up in winter. Farmers from across the plateau have finished harvesting and have plenty time to party, since preparations for next year's crops don't begin until the traditional Tibetan New Year, which this year falls on Feb 25. [Source: Trendy Traveler magazine China Daily February 1, 2009]

“But perhaps the best part of wintry Lhasa is watching the folk artists who enjoy themselves while entertaining audiences in the streets. Some devoted pilgrims set out on months-long journeys to pay homage at holy sites, measuring the route by prostrating themselves at each step. Monasteries in Tibet stage dances and ceremonies that regular tourists often miss. You can also visit hot springs, which are scattered all over Tibet. Yangbajain to the north of Lhasa is the most famous but locals talk of miraculous medical effects being experienced at many others, too. A route of sunshine in Tibet is recommended: From Lhasa, one can head east for Nyingchi, then turn west to Shannan, two prefectures with unique charms.”

My Travel Companions in Tibet

When I got to Lhasa some of the foreigners on the train were in my seven person group that was traveling to Everest and back to Lhasa. Another group from the train was traveling to Kathmandu. In my group there was an app designer from the snowiest place in America (the Upper Peninsula of Michigan), a math teacher from Queensland, a half -Columbian-half-New-Jersey scuba instructor, a German guy that just finished his PhD in chemistry, a female electronics engineer from Japan and an Irish guy that told a lot of sex stories. They were all in their late 20s, early 30s. I’m a 57-year-old house-husband-teacher living in Japan who spends most of his time making a website about different countries.

As I eluded to before its funny how a trip even to an extraordinary place like Tibet can be shaped by the hum-drum social dynamics of the people you are traveling with, especially when you are traveling on your own as I was. Among my travel mates, the math teacher, app designer and scuba instructor — all women who were 27 or so — formed the heart of the group. They met on the train from Beijing and bonded pretty tight — and boy could they yack. You are at some beautiful spot or checking out the locals and in the background are conversations about soul mates, tattoos and weddings. The members of my group drank practically every night (I joined in about half the time) and the day often began with discussions on who was and wasn’t hungover.

The three women embraced the Irish guy while the remaining three members of the group where on the periphery to varying degrees, with me perhaps the farthest from the center. The German guy was very sincere and sweet and generally tried hard to get along with everybody. The Japanese woman was often very quiet and participated in the group as need arose but generally seemed complacent and unperturbed by it all. As for me I generally had a good time but there were times I felt a little left out or was annoyed by the inanity of the constant chatter. I preferred talking to our guide Khamsang, who among other things told me that her mother-in-law had five husbands at the same time — all brothers (Tibet is one of the few places in the world where polyandry — the female counterpart of polygamy — is still practiced).

I only mention all this social life stuff because that is what traveling in Tibet entails unless you have the money for a personal guide and driver. It is not possible to travel independently in Tibet. Overall the foreign travelers that go Tibet are pretty diverse and come from all over — and the character of the groups can vary quite a bit — so at least its not like the backpacker, full-moon party scene you find in Thailand.

Visiting Lhasa

The Lhasa-Everest tour began with our arrival in Lhasa by train in the afternoon. After the police checked our permits we were taken to our hotel. We were advised to rest to adjust to the altitude but I ventured out to check out the Potala and do the kora (clockwise circumambulation) around it. As I said before the Potala is an awesome sight and so large — more than 1,000 rooms, 10,000 altars and 200,000 statues, with some saying it is the largest palace in the world — that is best appreciated from a distance. There is a large Chinese-made square across the street from the palace that serves as a good viewing spot. The next day my group visited the inside of Potala in the morning. Although certain places are off limits much of its open, including the modest places where the current Dalai Lama slept, meditated and met visitors before he was forced to flee Tibet in 1959.

In the afternoon we visited Jorkand temple, the most sacred site in Tibet. Inside were saw important Buddha statues and Tibetans making offerings of yak butter, money and tsampa (barley flour). Outside the kora was a moving stream of Tibetans — with some, mostly Chinese, tourists — about 15 people wide, many in traditional clothes. Among them were women with colorful aprons, long strings of braided hair and children on their backs; old men with fur hats and coats with sleeves that extend a foot or so beyond their hands; monks of varying ages in burgundy-colored robes; and young men from Kham (eastern Tibet and western Sichuan Province) with their long hair wrapped around their heads like turbans and decorated with red ribbons.

Visiting the Monasteries Near Lhasa

The second full day in Lhasa was spent visiting Drepung and Sera Monasteries, both within 20 kilometers of downtown Lhasa. Among the highlights of this day were the debating monks, slapping their arms and seemingly haranguing one another, in the Sera monastery courtyard; Sera’s intricate, preserved sand mandalas; and the kitchen at Drepung with its room-size pots used to feed the 6,000 monks who once lived at the monastery (now there are only about 600 of them). Drepung was a focal point of the protest that launched the 2008 riots in Lhasa. We had to go through a metal detector to enter the monastery as we did at other important sites in Lhasa.

As for Lhasa itself, yes it is being swallowed by the Chinese, but Tibetan life endures. There are large highrises in the Chinese part of the city, the roads are choked with vehicles, but the Tibetan old town is still very Tibetan and very robust. In the winter, I was told by our guide, Lhasa fills with farmers on pilgrimages, as there isn’t much farm work to do in the cold weather.

All’n all, on the surface anyway, it doesn’t seem like the Tibetans have such a bad lot. They are allowed to have two children — and many have more — while many Chinese still are only allowed to have one, and they seem to be able to go about their daily lives as they choose. Many Tibetans have embraced modernity — smart phones, Western clothes, Bollywood films and music — to varying degrees. But I guess one sign of how things really are between the Chinese and Tibetan is that they don’t seem to mix much.

From Lhasa to Shigatze

On the third full day of the six-day Lhasa-Everest tour, we took the long-scenic route from Lhasa to Shigatze. Stops along the way included viewpoints from the tops of passes and places along Lake Yambdrok, which snakes in between mountain slopes and has delightful turquoise color, freezing only a few weeks in the year (usually in February). There are fish in the lake but nobody fishes there due to the Tibetan custom of water burials. We also stopped at a large mountain glacier.

In Shigatse we checked out another monastery, Tashilhunpo Monastery, the traditional home of the Panchen Lama, the second most revered religious figure in Tibet after the Dalai Lama. The current 11th Panchen Lama — the one chosen by Beijing anyway — has only visited a few times and spends most of his time in Beijing (the Panchen Lama recognized by the Dalai Lama disappeared more than a decade and half ago when he was three and hasn’t been seen since). The 10th Panchen Lama visited the monastery at the age of 51 in the 1989 — after spending years in solitary confinement and under house arrest in Beijing — and suddenly died shortly after giving a speech critical of Chinese policy in Tibet. The official cause of death was listed as a heart attack but many Tibetans believe he was poisoned. The night of his death, according to an article in The New Yorker, some mysterious Chinese men reportedly showed up in his room. After his death his body was embalmed and gilded and interred in a stupa at Tashilhunpo Monastery. His daughter was brought up in the house of the actor Steven Segal in Brentwood, California.

Trip to Everest

The day-long road trip to Everest in Tibet started in Shigatse (officially known as Xigazê), which is a about a six hour direct drive from Lhasa. The drama of that leg of the trip began the day before as we tried to finish our itinerary of seeing a stunning Tibetan lake and glacier and make it to the Chinese government office in Shigatse in time to get our permits to enter the Everest area.

The first part of the trip from Shigatse to Everest Base camp is a six-hour journey on the paved Friendship Highway that goes to Kathmandu in Nepal. After the town of Tingri and a major check point — in which all members of our travel party had to show our passports and permits to police and we were almost forced back because something was not right with our driver’s papers — we turned off on a bumpy, dirt-gravel road to Everest Base Camp. The 90-kilometer journey on this road was slow going, taking about three hours to get to the base camp and three hours to get back to Tingri, with a flat tire thrown in. But the trip was well worth the stomach-churning switchbacks and the car-roof-head-hitting bumps.

The original plan of our tour was to drive from Shigatze to Rinpoche Monastery, the highest monastery in the world, near Everest base camp. But it was too cold to stay there so we went back to the town of Tingli and slept in a very basic, freezing cold guesthouse. There were celebrated New Years Eve with limited enthusiasm as everyone was tired from the long day of driving and visiting Everest. One of the highlights for me on the return trip from Everest was drinking cans of beer we carried in the mini-bus after they exploded due to the high altitude.

After the turnoff on the dirt road it was a long climb to the top of a large hill which offered the first view of 8,848-meter-high (29,029-foot-high) Everest — and what a stunning view it was too. There was Everest: the king of a massif — the Mahalangur Himal — that also includes 8,516-meter-high (27,040-foot-high) Lhotse, the world’s forth highest mountain, 8,485-meter-high (27,838-foot-high) Makalu, the world’s fifth highest mountain, and 8,188-meter-high (26,864) Cho Oyo, the world’s sixth highest mountain. From our vantage point their glacier-covered slopes stretched across the mid-part of the horizon, glistening in the mid-day sun, looking like they had been painted with vanilla ice cream that had been repeatedly melted and refrozen..

Everest Base Camp

Then it was back into the mini-bus for the trip to Everest base camp. After piling in, my travel mates expressed the kind of superlatives you might expect after witnessing such a sight — “incredible,” “awesome,” superb,” — and then it was planning time for what to do once we reached Everest base camp. Some members of the group debated whether to moon their butts or run completely naked in the snow. Others discussed who they were going to e-mail their Smartphone pictures to. One woman wanted to be photographed wearing a T-shirt of her father’s harmonica blues band. An Australian couple in another group wanted to pose a stuffed mascot for an office photo competition.

Needless to say when we arrived at Everest base camp there was no snow — except on the mountains — as was the case throughout Tibet for much of the trip, something that was surprising to most of us non-Tibetans who expected to see snow in the Land of Snow in December and January. Most of the warm clothes I brought were more useful in the cold hotel rooms than walking around in the daytime sun.

Anyway, at Everest base camp I tried to negotiate for two hours of exploring-around time but was only able to get one hour. Most members of the group were primarily concerned with what photos they were going to take. One woman from Queensland, Australia wanted to get back in the mini-bus as quickly as possible, where it was warm (What are doing at Everest in the winter, you ninny!). Thankfully, as far as I could tell, everyone kept their clothes on and their butts hidden. As for myself, I wanted to make the most of my hour. I decided I would hike as far as I could in half an hour and then walk back. In that half hour I was able to reach a glacier and scramble on top of it — most of it was covered in dirt and rocks — and made it as far as a small lake on the glacier, where I could enjoy one of the world’s best views all to myself, undistracted. There, the triangular north face of Everest rose up in front of me, filling my field of vision, with hurricane force winds blowing snow from the summit to form wispy, stratospheric clouds...Wow.

Image Sources: Seat 61, Wikimedia Commons, Nolls China Web site; CNTO; Perrochon photo site; Beifan.com; University of Washington; Ohio State University; UNESCO; Wikipedia; Julie Chao photo site

Text Sources: CNTO (China National Tourist Organization), China.org, UNESCO, reports submitted to UNESCO, Wikipedia, Lonely Planet guides, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, China Daily, Xinhua, Global Times, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Bloomberg, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Updated in September 2022