DOCTORS IN CHINA

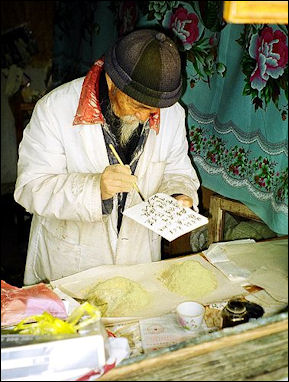

Chinese medicine

China had 1.1 million certified doctors of Western medicine and 186,947 traditional practitioners in the mid 2010s. There were 2.23 physicians per 1,000 people in 2019. This is up from 1.7 doctors per 1,000 people in 2002 when the U.S. had 2.5 doctors per 1,000 people. Put another way at that time there were 730 people per doctor in China, compared to one for 32,650 in Ethiopia, 611 in the United States and 210 in Italy. [Source: According to the CIA World Factbook; Ian Johnson, New York Times, October 10, 2015]

In 1949 there were only 33,000 nurses and 363,000 physicians were practicing in China. The number of physicians and pharmacists trained in Western medicine reportedly increased by 225,000 from 1976 to 1981, and the number of physicians' assistants trained in Western medicine increased by about 50,000. By 1985 the numbers had risen dramatically to 637,000 nurses and 1.4 million physicians. As of 2004, there were an estimated 164 physicians, 104 nurses, 29 pharmacists, and 4 midwives for every 100,000 people. In 2006, there were 1.6 physicians per 1,000 people, compared to 0.4 in low-income countries, 2.7 in the U.S. and 2.3 in high-income countries. [Source: Library of Congress, Worldmark Encyclopedia of the Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

The quality of doctors and they conditions they have to work under are particularly bad in rural China. According to the Financial Times: Just 10 percent of doctors in township healthcare centres, the lowest level of urban provision that are typically more rual than urban, have received formal medical training, according to a study in the BMJ in 2018. In the north-eastern province of Heilongjiang, more than 100 rural doctors resigned in June 2018, announcing in a letter that they were each owed tens of thousands of renminbi by a state insurance fund. [Source: Tom Hancock and Wang Xueqiao, Financial Times, December 31 2019]

There is a shortage of doctors in China, particularly general practitioners. There were only 4,000 general practitioners in all of China in the 2000s. In the 1980s, to address concerns over health, the Chinese greatly increased the number and quality of health-care personnel. Some 436,000 physicians' assistants were trained in Western medicine and had 2 years of medical education after junior high school. The number of students in medical and pharmaceutical colleges in China rose from about 100,000 in 1975 to approximately 160,000 in 1982. [Source: Library of Congress]

Articles on HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HEALTH CARE IN CHINA: HISTORY, INSURANCE AND POOR CARE IN RURAL AREAS factsanddetails.com; MEDICAL PRACTICES IN CHINA: SURGERY, TECHNOLOGY AND QUACKS factsanddetails.com; HOSPITALS IN CHINA: LINES, SCALPERS AND UNEQUAL CARE factsanddetails.com; BAREFOOT DOCTORS AND HEALTH CARE IN THE MAO ERA factsanddetails.com; PROBLEMS WITH HEALTH CARE IN CHINA: HIGH COSTS, INEQUALITY AND BAD MEDICINE factsanddetails.com; DOCTOR AND HOSPITAL VIOLENCE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; HEALTH CARE REFORMS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; Center for Disease Control on China CDC World Health Organization on China who.int/countries/chn ; Wikipedia article on Public Health in China Wikipedia

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “China's Healthcare System and Reform” by Lawton Robert Burns and Gordon G. Liu Amazon.com; “China's Urban Health Care Reform: From State Protection to Individual Responsibility” by Chack-kie Wong , Vai Io Lo, et al Amazon.com; “Maternal Healthcare and Doulas in China: Health Communication Approach to Understanding Doulas in China” by Zoe Z. Dai Amazon.com; “Medicine in Rural China: A Personal Account” by C. C. Chen and Frederica Bunge Amazon.com; Barefoot Doctors and the Mao Era: “A Barefoot Doctors Manual: The American Translation of the Official Chinese Paramedical Manual” by John E. Fogarty Amazon.com; “Barefoot Doctors and Western Medicine in China” by Xiaoping Fang Amazon.com; “Intimate Communities: Wartime Healthcare and the Birth of Modern China, 1937-1945" by Nicole Elizabeth Barnes Amazon.com; “China and the Cholera Pandemic: Restructuring Society under Mao” by Xiaoping Fang Amazon.com; “The People's Health: Health Intervention and Delivery in Mao's China, 1949-1983 (Volume 2) by Xun Zhou Amazon.com

Overworked Doctors in China

Many doctors in China are overworked and stressed out. They typically see 50 to 60 patents a day and often spend less than five minutes with each one. Many doctors are women. Many of the male ones smoke. In the 2000s, more than half of Chinese doctors smoke. There were 20,000 acts of violence at Chinese hospitals in 2013., mostly aimed at doctors viewed as uncaring or corrupt.

Hospitals are understaffed and overwhelmed. Specialists are overworked, seeing as many as 200 patients a day. Siu-wee Lee wrote in the New York Times: On some mornings, Dr. Huang Dazhi, a general practitioner in Shanghai, rides his motorbike to a nursing home, where he treats about 40 patients a week. During lunchtime, he sprints back to his clinic to stock up on their medication and then heads back to the nursing home. Afterward, he makes house calls to three or four people. On other days, he goes to his clinic, where he sees about 70 patients. At night, he doles out advice about high-blood-pressure medications and colds to his patients, who call him on his mobile phone [Source: Siu-wee Lee, New York Times, September 30, 2018].

“For all this, Dr. Huang is paid about $1,340 a month — roughly the same he was making starting out as a specialist in internal medicine 12 years ago. “The social status of a general practitioner is not high enough,” Dr. Huang said, wearing a gray Nike T-shirt and jeans under his doctor’s coat. “It feels like there’s still a large gap when you compare us to specialists.”

China's Poorly Paid Doctors

Fully-trained doctors are notoriously underpaid. They generally receive only a few hundred dollars a month in salary — often less than what some taxi drivers make — and are expected to supplement their income with “red envelope money,” which the families of patients pay for better care, and by selling drugs or performing operations in which they take a cut. Some doctors stop treatment and demand more money before they continue. Doctor salaries in 2012 ranged from 4,000 yuan ($628) to 10,000 yuan ($1,570) a month.

One medical student in Beijing told the New York Times that even in a top hospital, pay levels are barely adequate. The investment it takes to become a doctor and what you get out of it are greatly out of proportion, he said. A doctor has to spend 10 years on education. Then, if he only gets the government-given level of income, well, that’s really not enough....Even with conference fees, speaking fees and other income added in, the total income is still low. Even if we are doctors, we still have to make sure that we have food to eat and clothes to wear.

In 2014, a doctor just completing medical school in Beijing earned about $490 a month including bonuses — roughly the same as a taxi driver. Around that time construction workers from China earned about $7,300 a years during their first year of work and $15,000 during their second year. One such worker who died in Malaysia Airlines Flight MH370 plane crash, had finished five years of medical school in a provincial Chinese city but decided there were better opportunities doing manual labor in Singapore than practicing medicine in China. [Source: Leo Lewis, The Times of London, April 2014]

Huge Pay Gap for Chinese Doctors

More than 60 percent of doctors in China are paid less than $14,000 a year according to consultancy McKinsey in 2019, a condition that has led to a shortage of doctors and a wave of resignations in rural areas. But not all doctors receive such low salaries. The Financial Times reported: “As a top neurosurgeon in Shanghai’s best state-run cancer hospital, Song Donglei’s skills were in such demand that he spent weekends flying to remote regions of China to conduct surgeries — helping him to earn an annual salary of more than $570,000. “Just like table tennis, it’s important to be on the top national team,” he said. “I was in the top five at the hospital — that’s like being on the Olympic team.”[Source: Tom Hancock and Wang Xueqiao, Financial Times, December 31 2019]

“The salary gaps highlight the unequal distribution of resources in China’s medical system — with state-run hospitals in the largest cities hosting world-class professionals, while doctors in smaller provincial hospitals are generally less skilled. Wage disparities within professions are common in China, where there are marked differences between regions in terms of prosperity and development. But they are especially stark in healthcare, in part due to the “superstar effect” which sees patients flock to see “celebrity doctors”. That process can further erode incomes for less well-known doctors in local hospitals.

“Chance treatments can also help catapult a doctor into celebrity status. Mr Song’s fame was boosted when he treated famed comic actor Zhao Benshan for an aneurysm in 2009. At Mr Song’s Shanghai hospital about 95 percent of patients travelled from outside the city, he said. Mr Song left his state-run hospital five years ago to seek more freedom in private practice. Since then, salaries for top doctors have continually increased due to rising demand from affluent patients. “Much of a Chinese doctor’s income isn’t earned inside their hospital. Instead, once you are famous, others will request you to perform surgery,” said Mr Song.

Dozens of Chinese doctors earn more than $725,000 a year, but an elite group of about a dozen earn $1.45 million, according to industry insiders — more than twice the average for a New York neurosurgeon of $616,000, according to the ERI Economic Research Institute. However, they are an exception. “The average doctor’s wage in China is 1.6 times the average wage, compared to more than three times in developed countries,” said John Lin, a partner at EY in China. There is a lack of high-quality medical resources in China, so some excellent doctors have much more work than average doctors,” said Zhao Bing, a healthcare analyst at Huajing Securities, a brokerage. “To change this situation, we must strengthen the training of grassroots doctors.” [Source: Tom Hancock and Wang Xueqiao, Financial Times, December 31 2019]

Lack of Respect for Doctors in China

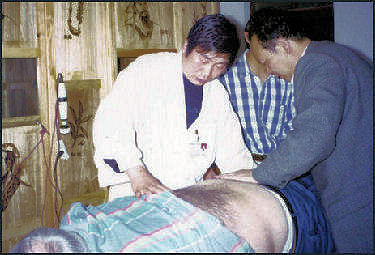

Treatment by a doctor

Siu-wee Lee wrote in the New York Times: In a country where pay is equated with respect, the public views family doctors as having a lower status and weaker credentials than specialists. Among nearly 18,000 doctors, only one-third thought that they were respected by the public, according to a 2017 survey by the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Peking Union Medical College, Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Harvard Medical School, the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the U.S. ““There is no trust in the primary care system among the population because the good doctors don’t go there,” said Bernhard Schwartländer, a senior aide at the World Health Organization and its former representative to China. “They cannot make money.” [Source: Siu-wee Lee, New York Times, September 30, 2018]

“Dr. Zhu Shanzhu, a teacher in the program, said one of the main problems was that doctors did too few physical examinations in the community clinics. Many of them lean toward prescribing medicine instead. Clinical reasoning, too, is poor, she said. In 2000, Dr. Zhu designed a course to train general practitioners in Shanghai’s Zhongshan Hospital, at the request of its director. Her first course was free. No one showed up.

Nearly two decades later, Dr. Zhu, 71, says that training is still insufficient and doctors do not spend enough time studying the latest research and techniques in their field. “If there’s more money, the good people will come,” she said. “And a high economic status will elevate the social status.” The government has pledged to increase the salaries of family doctors. But Dr. Zhu isn’t optimistic. “All these ministries need to coordinate among themselves,” she said. “Our country’s affairs, you know, they aren’t easy.”

Complaints About Pediatricians in China

There is a shortage of at least 200,000 pediatricians in China currently, according to K. K. Cheng, a professor with University of Birmingham, who specializes in epidemiology and the development of primary care in China. [Source: Liu Zhihua, China Daily, November 13, 2013]

The China Daily reported: “A Beijing resident who only wants to be known as Liu Lan, says her blood boils whenever she recalls her experience in a top children’s specialist hospital in Beijing. Her son, now 6, had severe oral ulcers when he was 3, and examinations indicated abnormality in his blood. After over a year of visiting the hospital, where her son underwent a series of blood tests, a bone marrow examination, and various medication, his doctor, a top expert in children’s blood diseases, discharged the boy, saying he didn’t have leukemia.

“Liu thought her son was cured, but soon after, the boy developed severe oral ulcers again, and blood test showed he was still ill. “What makes me most angry is, the expert told me from the very beginning that I should have another child … It is as if my son was dying. “To see the expert, I took my son to the VIP department of the hospital. It was expensive. But she didn’t even tell us the truth that she had failed to make a diagnosis,” Liu says. “Parents complain that doctors only spend one to two minutes on their children, say a few words, and are irresponsible. But for those of us with 100 patients a day, if we spend too much time on one patient, we can’t finish our work, and it is unfair to others. “We have to be focused and fast, but we are just humans, and we become tired and irritated because of work overload day in, day out.”

“While parents feel angry and disappointed that doctors don’t stand in their shoes, doctors also complain that parents hold unrealistic expectations about their performance. “Good hospitals for children are always packed with people, and we are so busy seeing more than 100 patients a day,” says Jiang Yuwu, director of the pediatrics department of Peking University First Hospital.

Cycle of Poor Pay for Doctors and Poor Chinese Hospitals

“It’s a vicious circle, said Cao Zemin, director of social services at Xiangya Hospital in Changsha, the chief city of Hunan Province. Patients shy away from small hospitals because many members of the staff have only a bachelor’s degree, if that, Dr. Cao said, adding, Some have never received any formal training, like the barefoot doctors from before who have not had a single day of standardized, regulated medical education.”[Source: New York Times, Jingying Yang, April 26, 2010]

“With fewer patients, the doctors have fewer chances to learn and improve their technique, not to mention lower salaries. So students with the most potential head for the bigger hospitals, and the patients follow. Thousands of medical students bemoan the lack of job opportunities after graduation, yet the problem of skill shortages in second- and third-tier hospitals remains intractable.”

“The Chinese medical industry very much needs talented people, Dr. Cao said. It’s true that some students cannot find jobs after graduation. The key problem is that they all want to stay in the big cities. They don’t want to go to the countryside or to the lower-status hospitals. Out of about four million medical graduates a year, fewer than half find jobs in big hospitals. The rest continue in postgraduate training to improve their job prospects or look for jobs elsewhere in the health care industry — in pharmaceuticals, biotechnology or medical supplies.”

“Two government-backed efforts could help to make better use of the pool of trained medical talent: an expansion of higher-fee hospitals and regulated residency programs.”

Profits Versus Serving the People

One person wrote on an Internet chat line that doctors in one clinic delivered 95 percent of the babies by Caesarean section to make more money (regulations prevent clinics from charging high fees for natural births). Nationwide the figure is about 50 percent, with 70 percent not unusual for some regions. Before 1979 only around 10 percent of births were by Caesarian section.

In the mid-1980s, Siu-wee Lee wrote in the New York Times: “ As hospitals started investing in high-tech machines and expanded to meet their new financial needs, medical students were drawn to them. Many believed that being a specialist would guarantee them an “iron rice bowl,” a job that was secure with an extensive safety net that included housing and a pension.[Source: Siu-wee Lee, New York Times, September 30, 2018]

“Dr. Huang initially followed the more lucrative path. After graduating from medical school in 2006, he started working as an internist in a hospital in Shanghai. But he kept seeing patients with simple aftercare needs like removing stitches, changing catheters and switching medication. “These things really should not be done by us specialists,” he said.

“When Dr. Huang saw a newspaper article about general practitioners, he decided to enroll in a training program in 2007. He was inspired by his aunt, a “barefoot doctor” in Mingguang, a city in Anhui Province, one of the poorest regions in China. As a boy, he had followed his aunt as she went to people’s homes to deliver babies and give injections. “After becoming a doctor, I’ve realized that the people’s needs for ‘barefoot doctors’ is still very much in demand,” he said.

Doctors and Bribes in China

Doctors often earn several times their salary taking bribes or commissions on unnecessary prescriptions and tests. Bribes paid to doctors are almost prerequisites to getting decent medical care and doing business in the health care sector in China. In August 2005, Health Minister Gao Qiang criticized China’s hospitals for being greedy and putting profit ahead of their social functions.

There have been cases of doctors demanding money up front before they perform a C section. The Times of London described one man who paid $288 to have his daughter treated for an ear infection at a Beijing hospital and 6-year-old boy scalded by boiling water who died of his injuries after being turned away from a hospital in Xinjiang because his parents couldn’t afford the $2,700 deposit demanded by the doctors for treatment.

Siu-wee Lee wrote in the New York Times: “It goes back to the market reforms under Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s. After the government cut back subsidies to hospitals, doctors were forced to find ways to make money. Many accepted kickbacks from drug companies and gifts from patients. In a survey of more than 570 residents in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou conducted in 2013 by Cheris Chan, a sociology professor at the University of Hong Kong, more than half said they and members of their family gave “red envelopes” as cash gifts to doctors for surgery during 2000-12. [Source: Siu-wee Lee, New York Times, September 30, 2018]

“Dr. Yu Ying, who worked as an emergency room doctor at Peking Union Hospital, one of China’s top hospitals, said she was once a valiant defender of her profession. On her widely followed account on Weibo, China’s version of Twitter, she pushed back against critics who called doctors “white-eyed wolves.” After I discovered the truth, I really had to give myself a slap in the face,” she said.

“Dr. Yu said she had heard accounts from outpatient doctors who accepted thousands of dollars in kickbacks from drug companies — “cash that was bundled into plastic bags.” “In the entire system, the majority of doctors accept red envelopes and kickbacks,” she said. The corruption is endemic. GlaxoSmithKline paid a $500 million fine in 2014, the highest ever in China at the time, for giving kickbacks to doctors and hospitals that prescribed its medicines. Eli Lilly, Pfizer and other global drug giants have settled with regulators over similar behavior.

Contracts with Family Doctors Improve Health Care in China

Siu-wee Lee wrote in the New York Times:“To help change the culture” that overburdens China’s hospitals, “ China is pushing each household to sign a contract with a family doctor by 2020 and subsidizing patients’ visits. General practitioners will also have the authority to make appointments directly with top specialists, rather than leaving patients to make their own at hospitals. Such measures would make it easier for patients to transfer to top hospitals without a wait, while potentially giving them more personalized care from a doctor who knows their history. It could also cut down on costs, since it is cheaper under government insurance to see a family doctor. [Source: Siu-wee Lee, New York Times, September 30, 2018]

“After the government’s directive, Dr. Yang Lan has signed up more than 200 patients, and monitors their health for about $1,220 a month. From her office in the Xinhua community health center, a run-down place with elderly patients milling about in the corridors, she keeps track of her patients with an Excel sheet on her computer. She said she had memorized their medical history and addresses.

“Dr. Yang, 31, said her practice was largely free of grumpy patients and, as a result, “yi nao.” She sees 50 to 60 patients in a workday of about seven and a half hours. In the United States, a family doctor has 83 “patient encounters” in a 45-hour workweek, according to a 2017 survey by the American Academy of Family Physicians. That’s about 16 patients in a nine-hour workday.

“The patients get something, too — a doctor who has time for them. Every three months, Dr. Yang has a face-to-face meeting with her patients, either during a house call or at her clinic. She’s available to dispense round-the-clock advice to her patients on WeChat, a popular messaging app in China. A patient is generally kept in the waiting room for a brief period and, if necessary, gets to talk with her for at least 15 minutes.

“On a hot summer day, an elderly woman with white hair walked into Dr. Yang’s clinic. She has cardiovascular disease, and Dr. Yang told her to watch what she ate. Next, a man with diabetes dropped in. “Hey, you got a haircut!” Dr. Yang exclaimed. At one point, four retirees swarmed Dr. Yang’s room, talking over one another. “I think she’s really warm and considerate,” said Cai Zhenghua, the patient with diabetes. He used to seek treatment at a hospital, he said, adding, “The time spent interacting with doctors here is much longer. ” [Source: Siu-wee Lee, New York Times, September 30, 2018]

Increasing the Number of General Practitioners in China

China has one general practitioner for every 6,666 people, compared with the international standard of one for every 1,500 to 2,000 people, according to the World Health Organization. Siu-wee Lee wrote in the New York Times: The government aims to increase the number of general practitioners to two or three, and eventually five, for every 10,000 people, from 1.5 now. But to even have a chance of reaching its goals, China needs to train thousands of doctors who have no inkling of how a primary care system should function and little interest in leaving their cushy jobs in the public hospitals. It is forcing hospital specialists to staff the community clinics every week and paying those doctors subsidies to do so. It is also trying to improve the bedside manner of doctors with government-backed training programs. [Source: Siu-wee Lee, New York Times, September 30, 2018]

“In Shanghai, Du Zhaohui, then the head of the Weifang community health service center, introduced a test that uses mock patients to evaluate the care and skills of general practitioners. The doctors have 15 minutes to examine “patients.” The teachers use a checklist to grade the doctors on things like making “appropriate eye contact” and “responding appropriately to a patient’s emotions.”

At a recent test, one doctor, wearing crystal-studded Birkenstock sandals, examined a patient who had insufficient blood flow to the brain by swinging a tiny silver hammer, the equipment that is used for testing reflexes. “That isn’t the right way,” Li Yaling, head of the center’s science and education department, said with a sigh. She said the doctor was probably too nervous and should have used a cotton swab to stroke the soles of the patient’s feet instead.

Establishing Residency Programs for Doctors in China

For a long time China didn't have doctor residency programs like those found in other countries. In many places in China this is stilll the case. Jingying Yang wrote in the New York Time: “Residency programs have been established in Beijing, Shanghai and Tianjin offering graduates three years of specialist training at leading research and teaching hospitals Wang Jianxiang, a professor of medical science at the Institute of Hematology and Blood Diseases Hospital in Tianjin, said the government was working to expand the programs to allow rural hospitals to send doctors for residential training.” [Source: Jingying Yang,, New York Times, April 26, 2010]

“Still, Dr. Cao said, the programs are not ideal. In contrast with the American system, in which graduate students complete a residency before taking a job, their Chinese counterparts look for a job immediately after graduating, sign a contract with a hospital and then are assigned by the hospital to complete a residency before starting work.”

“Dr. Wang said, After three years in a big city, you might want a different job in a different place, but you have to go back to the hospital where you signed your contract. Or for the hospital, they hire people three years ahead of time...On the books, they have all these doctors, but in reality, these doctors aren’t working or earning the hospital any income. What’s more, for these three years, the hospital has to pay those doctors, so it really becomes an economic burden.”

Image Sources: Wiki Commons, University of Washington; Harvard Public Health; Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2022