POLITICAL ACTIVITY AT CHINESE UNIVERSITIES

Jonathan Kaiman wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “Historically, China's universities have occupied central roles in many of the country's political upheavals. The Chinese government is all too aware of that fact and has devised elaborate systems to maintain social stability on campuses, including extending the reach of the Communist Party through its own powerful student organizations. [Source: Jonathan Kaiman, Los Angeles Times, December 9, 2012]

“Peking University's history of student activism dates to 1919. Its students sparked the May 4 Movement after converging on Tiananmen Square in central Beijing to protest the government's weakness against foreign imperialism. Seventy years later, in 1989, they returned to the square en masse demanding transparency, democracy and rule of law — protests that led to the brutal June 4 crackdown.

“The authorities' fear of another Tiananmen-like incident is palpable, leading them to censor even online keywords related to those protests. After anonymous calls for an "Arab Spring"-style "Jasmine Revolution" in China began to circulate online in March, the Peking University tuanwei canceled student group meetings on short notice. It arranged small meetings with students in dorms and warned them not to do anything extreme. And Peking University authorities announced a program that would require counseling for a "targeted group of students," including those with "independent lifestyles" and "radical thoughts."

“In 2003, four members of a Peking University-based discussion group were sentenced to long prison terms for subversion after meeting in a neighborhood apartment to discuss political reform. One member had secretly filed reports to the Ministry of State Security that included details of their conversations. "Talking about politics is extremely dangerous, especially for a group of students," said Jiang Jian, a recent graduate of Tsinghua University.

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Fragile Elite: The Dilemmas of China's Top University Students” by Susanne Bregnbaek Amazon.com; “River Town: Two Years on the Yangtze” by Peter Hessler Amazon.com; “Academic Experiences of International Students in Chinese Higher Education” by Mei Tian, Fred Dervin, et al. (2020) Amazon.com; “Little Emperors and Material Girls: Sex and Youth in Modern China” by Jemimah Steinfeld Amazon.com; “Studying in China: A Practical Handbook for Students” by Patrick McAloon Amazon.com; “Foreign Language Anxiety. A Case Study of Chinese University Students Learning English as a Foreign Language” by Yin Xiaoteng Amazon.com; “Dreams of Flight: The Lives of Chinese Women Students in the West” by Fran Martin Amazon.com

Student Groups and Tuanwei — the University Wing of the Communist Youth League

Jonathan Kaiman wrote in the Los Angeles Times: Student groups at public universities in China “are administered by the school's Communist Youth League Committee, or tuanwei, a student-staffed organization with direct ties to university officials. The tuanwei authorizes student groups' formation, signs off on their meetings and dictates where and when they may hold events. The tuanwei is part of the Communist Youth League, a "mass youth organization" of 14- to 28-year-olds that had 73 million members at the end of 2006. "Everyone is in the Youth League," said Hu Yunzhi, a 20-year-old tuanwei member at Peking University. "If you don't join in high school, people will think there's something wrong with you." [Source: Jonathan Kaiman, Los Angeles Times, December 9, 2012]

“Success in the tuanwei can open doors later. Elite members are often given spots in top graduate programs regardless of their academic standing. Many use their tuanwei connections to land cushy jobs in prestigious government departments. Hu said that, as part of the Peking University tuanwei's propaganda and research department, he is responsible for reporting on his classmates' political sentiments. Hu solicits opinions on campus lawns, in classrooms, even in late-night conversations with his roommates. "If something sensitive happens, we have to give feedback to leaders immediately, even if we have a big exam," he said.

“Zhang Ming, a professor of sociology at People's University in Beijing, said that for the tuanwei — as well as for the Communist Party at large — maintaining control is paramount, and corruption is endemic. "Obviously when they have power like this, the Student Union or tuanwei, they tend to abuse their privileges," he said. Although Hu said his reports are intended to gauge public opinion and not to identify potential troublemakers, surreptitious informing has had disastrous consequences for some student groups.

This means that it can be a tortuous endeavor for students to simply engage in extracurricular activities. Registered groups are tightly controlled by a draconian bureaucracy, and unregistered groups like Beidou often face restrictions, intimidation and worse. Zeng Zhen, a 19-year-old economics student at Peking University who directs a student group called Alliance of Students Against Poverty, said the tuanwei often makes forming new groups more trouble than it's worth. Rejections are common. Aspiring student leaders must take examinations about school regulations and undergo "trial periods" that drag on for weeks.

“If a group finally wins permission to form, each of its activities must be independently approved. Should a group want to host a speaker from outside the university, it must submit a full draft of the speech to the tuanwei in advance. "Even if we are allowed to enter a university to give a speech, the event could still be disrupted," said Chen Ziming, an independent scholar who spent 13 years in prison for helping organize the Tiananmen Square protests. "Sometimes they'll just turn the lights off or cut the power."

Intimidation of Student Groups at Chinese Universities

Jonathan Kaiman wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “It could have been any of his recent articles: The one on violent revolution was particularly sensitive, as was another on China's history of capital punishment. But it was probably the article about how to behave if the authorities "treat you to tea" — a euphemism for interrogation — that got Bo Ran, a 23-year-old recent graduate of Peking University, treated to tea himself. [Source: Jonathan Kaiman, Los Angeles Times, December 9, 2012]

“Bo is a former editor in chief of Beidou, a scrappy 4-year-old online student magazine that operates out of an apartment painted neon green near the university. The men who took him to a small cafe near campus last fall did not reveal their names or affiliations. They told Bo he was being watched. One suggested he be more "moderate." "They weren't very detailed," Bo said. "But based on what they were saying, I could tell that they understood our website really well."

“Although some articles border on the provocative, Beidou has steered clear of sensitive topics, such as Tiananmen Square, the recent scandal involving politician Bo Xilai and the once-in-a-decade leadership transition that began last month at the 18th party congress. Yet despite the magazine's circumspection, two other editors were also "treated to tea" within the last year. A phone call from the police this year led Beidou's leaders to cancel a full meeting of staff and contributors.

“Jiang said a cloud of paranoia can sometimes envelope students working at Beidou. He recalled getting a call from a man claiming to be a Peking University security guard while editing copy late one night. The man said he was tracking down a thief and implored Jiang to circulate a call for help on Beidou's website. Jiang's first thought was that the man may have been testing Beidou's organizational prowess: If the site could help track down a thief quickly, then perhaps it could arrange a demonstration just as rapidly. He told the caller he would think about it, and then replied in a text message that there was nothing he could do. He never heard from the mysterious man again.

Student Activism Versus Getting Ahead in China

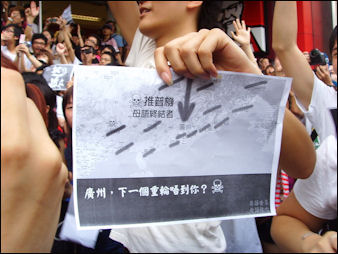

student protest in Guangzhou in 2010

Beida has a long tradition of activism. It was founded by Cai Yuanpei, an educator and revolutionary. Its students were among the first Red Guards in the Cultural Revolution and were leaders of the 1970 Democracy Wall. The Tiananmen Square demonstrations were started by Beida students fed up with conditions in their dormitories and their country.

Things are much different today. Few waste their time on politics. Most are obsessed with getting good TOEIC scores, gaining entrance to American universities, landing good jobs or getting a hold of the latest computer software. One professor told Time "Students these days are typically aloof from politics. They're mainly interested in going abroad or making money.”

One student said, "You can't get things done without money. The government won’t allow us to speak out, so we'll engage in business, we'll publish, we'll go overseas." Another student said, "Student's are studying like mad. After school, they study a law, business, foreign language — even driving. They know it’s a tough world out there, and it's not enough to get a Beida bachelor's degree."

University students that show too keen an interest in reformist politics risk being discriminated against. Professors that criticize the government are either fired or kept on the faculty but are barred from teaching.

Engineers, See Labor

Students Screened for 'Radical Thoughts' at Peking University

Tania Branigan wrote The Guardian: “One of China's most prestigious universities has announced plans to screen all students and identify those with "radical thoughts" or "independent lifestyles", provoking angry reactions from undergraduates and comparisons to the Cultural Revolution. Administrators at Peking University say their focus is on helping those with academic problems. But the institution's announcement identifies nine other categories of "target students" — including people with internet addiction, psychological fragility, illness and poverty, plus those prone to radical thinking and independent or "eccentric" lifestyles. It adds: "The objective of the consultation programme is to help individual students achieve an all-around and healthy development." It says officials should respect students' individual differences but they must "address ideological problems and practical issues" and help to guide them. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, March 28, 2011]

Zha Jing, deputy director of the office of student affairs, told The Guardian the university was not trying to punish or control students but to "create an environment for healthy growth". Zha said: "We've noticed ... some students having radical thoughts and bigoted character and encountering difficulties in interpersonal communication, social adaptiveness and their studies. They cannot analyse and handle their problems in daily life in a rational and manifold way. "For example, they cannot get on well with roommates, cannot handle love setbacks in a calm way and cannot adapt to career life after graduation.” Earlier, when asked about students with "radical thoughts", he told the Beijing Evening News: "For instance, some students criticised the university just because the food price in the canteen was raised by 2 jiao [2p]."

While some students have voiced support for the university, others are furious. One student told the Beijing Evening News that the college where the scheme had been piloted was known for liberal thinking, but that the new rules would make people think it wanted to cage its students' minds. Zhang Ming, a politics professor at Renmin University, also in Beijing, said: "For a university to see a student having radical thoughts or independent thinking as a bad thing that has to be punished, is terrible.”

"College students are all young and energetic; it is normal for them to have differentiated, active thoughts. It is their right to be radical. If a university punishes this, the university is morally degenerating."Xiong Bingqi, deputy director of the 21st Century education research institute in Beijing, told China Daily: "The university is somewhere to cultivate people's independent personalities and thinking, so it's totally wrong for Peking University to intervene in students' freedom to express their different opinions."

Crackdowns on Marxist Groups at Peking University

In 2018, Peking University (“PKU) accused student Marxists of criminal activity after the apparent kidnapping of two students. The Peking University committee of China's ruling Communist Party declared the establishment of an ‘internal control and management’ office to enforce discipline on campus, including day-to-day inspections and patrols on school grounds,” according to CNN. PKU authorities also “sent a message to all students, accusing Marxist activists of ‘criminal activity,’ and warning that ‘if there are still students that want to defy the law, they must take responsibility,’” according to Agence France-Presse. At the same time there was a petition demanding the release of detained students and workers. [Source: Jeremy Goldkorn, Sup China, November 15, 2018]

A couple month earlier, the Financial Times reported: Peking University threatened to shut down its student Marxist society amid a continuing police crackdown on students who support workers in a dispute over trade union organisation. Peking University’s Marxist Society was not able to re-register for the new academic year because it did not have the backing required from teachers, the society said. “Everyone can see what the Peking University Marxist Society has done over the past few years to speak out for marginalised groups on campus,” it added. [Source: Yuan Yang and Xinning Liu, Financial Times, September 23, 2018]

“The threat to close the society follows a summer of student and worker unrest in the Chinese manufacturing hub of Shenzhen. Students from Peking and other elite Chinese universities were detained for supporting workers trying to organise a trade union at a Jasic Technology factory. While workers’ protests have become more common in China, the support of a small yet growing student movement has made the Jasic protests politically sensitive. Zhan Zhenzhen, a member of the Marxist Society at Peking University, was among those arrested in Shenzhen in August 2018. In July, police detained about 30 workers in the biggest such arrest since 2015. In August, police wearing riot gear stormed a student dormitory and took away about 40 students who had been supporting the workers, according to witnesses.

“Mr Zhan and the Marxist Society initiated an investigation into working conditions for low-paid workers at Peking University in 2018. The group said its focus was labour rights, and it gained media attention in 2015 when it published an earlier working conditions report. The Marxist Society said it had approached teachers in the university’s department of Marxism for support with registration but had been refused, with no explanation. A teacher from another department had volunteered to register the society but said his offer was rejected by the university’s Student Society Committee. Chinese leader Xi Jinping visited Peking University in 2018 to commemorate the 200th anniversary of Karl Marx’s birth. “Peking University is the first place to spread and study Marxism in China. It makes a great contribution to the spread of Marxism and the foundation of China’s Communist Party,” he said.

In August 2022, 22-year-old Yue Xin, was taken into custody 24 along with about 50 other activists, many of them young Marxists, who were involved in a labour rights protest in Shenzhen in support of for workers attemptiing to unionize at Jasic Technology. She had earlier accused Peking University of trying to silence her for demanding information about the handling of a sexual misconduct case that led to a student’s suicide 20 years ago – one of China’s most discussed #MeToo incidents. For several weeks the whereabouts of Yue, as well as her mother, was unknown. A few weeks before her detainment she graduated from Peking University’s School of Foreign Languages. [Source: Guo RuiMimi Lau, South China Morning Post, October 12, 2018]

According to the South China Morning Post: “In April, as the #MeToo movement gained traction on Chinese campuses and in workplaces, she filed a formal request to the college demanding that it disclose information about its handling of a sexual misconduct case involving a professor that resulted in the suicide of a student two decades ago. Yue then wrote an open letter accusing the college of trying to muzzle her by pressuring her family and suggesting she might not be allowed to graduate, leading to a public backlash against the university on social media. In July, Yue turned her focus to a labour dispute at Shenzhen-based Jasic Technology.

Deers Vs. Horses — Battle Between Marxist Groups At Peking University

“Wherever Yue and Gu are, that’s where I will be,” Zhan Zhenzhen, a Marxist at Peking University, told SupChina in November 2018. “Wherever they stand, that’s where my brightest prospects lie.” A few weeks after that Sup China reported: It seems that Zhan has now indeed joined his classmates Yue Xin, Gu Jiayue, and a half-dozen other missing Marxist student activists. According to a VOA report (in Chinese), Zhan was detained in Changsha, Hunan on January 2 after participating in celebrations for the 125th anniversary of Mao Zedong’s birth a week before, held in Mao’s hometown of Shaoshan, Hunan. On January 4, Peking University announced Zhan had “dropped out school,” a statement that clashes with rumors circulating on PKU forums that he was in fact expelled, under the pretext of missing two weeks of class. Either way, we have no way of knowing: sources close to Zhan report that he has been unreachable since December 26. [Source: Eddie Park Sup China, January 9, 2019]

“Beatings, interrogations, kidnappings, expulsions. One by one, Peking University’s Marxist student activists, starting with those who participated in the Jasic Workers’ Solidarity Group protests in Huizhou in the summer of 2018, are getting picked off like flies. With every reprisal, the strength of this group wanes: During the first months of the academic year, they distributed fliers and organized joint runs around campus in response to the university’s inaction in inquiring about Yue and Gu’s whereabouts (both are PKU alumni). An ensuing wave of arrests and kidnappings brought a hiatus to their activities, which resumed on December 28 when they made a bold return by holding placards outside a science building on campus, protesting the university administration’s decision to completely reshuffle the Marxist society — kicking out its original members and replacing them with 32 Communist Youth League cadres — under the pretext that it had “severely deviated” from promises made when they registered and had repeatedly organized activities that violated regulations. The protesters were quickly subdued and taken into the science building, where after an 18-hour interrogation they emerged, smiling radiantly, linking arms to film a video that was uploaded onto the Facebook page of “Global Support for Disappeared Left Activists in China,” picking up a little over 700 views.

“This feeble response is the least-pressing concern for the beleaguered group, which now finds itself locked in an ideological battle with its Youth League-backed namesake and sworn enemy. Since last week, the “old” and “new” Marxist societies have been publishing daily essays defending their understanding of Marxism, aiming direct rebuttals at the leaders of the opposing faction.

“The Peking University Marxist civil war started on December 28: While the “old” Marxists were getting beaten up and dragged on the floor, the “new” Marxists were conducting their first-ever group reading session, ironically in the building directly opposite the scene of the protest. The format of the new society’s inaugural event sets them apart from their predecessors: It’s the antithesis of an activist movement. While the “old” Marxist society’s members prided themselves on abandoning the company of books for that of the cooks, cleaners, and rubbish collectors living on campus, their successors already made clear its intention of keeping close ties to the establishment: The group reading session was led by Sun Xiguo, dean of the School of Marxism, and Yang Lihua, a professor at the Department of Philosophy.

“Even more telling is the topic of discussion, chosen by the two professors and society leaders: Confucianism. As described by the group’s first essay on WeChat, seen over 37,000 times, the reading session’s first order of business was Professor Wang guiding the students in reading “Reflection on Things at Hand: The Neo-Confucian Anthology, a 12th-century compilation of all the new ideas and interpretations of the Confucian tradition then being developed, co-authored by Zhu Xi and Lu Zuqian. Known mainly by students of East Asian intellectual history, this obscure book is named after a saying found in Confucius’ Analects: “Study widely and with purposefulness; ask sharp questions and approach the underlying principle”.

For the complete article from which this much of the material here is derived see Deer Vs. Horses u.osu.edu/mclc

Image Sources: 1) Louis Perrochon ; 2, 3) Ohio State University; 4) Nolls China website; 5) Bucklin archives; 6) Poco Pico blog ; Wikicommons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2022