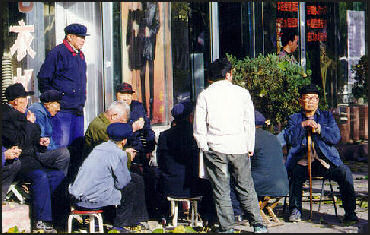

GAMBLING IN CHINA

Men playing cards Chinese love gambling. They have traditionally had no moral or religious qualms about betting money. Gambling rooms have typically been fixtures of Chinese communities. In many ways the stereotype that Chinese love gambling comes more from the behavior of Chinese in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Macau than in mainland China but as mainland Chinese have become more affluent their love of gambling seems also to have been reawakened.

Dicelike objects have been found in Chinese excavations dating back to 3000 B.C. The A.D. 3rd century scholar Wei Qiao lamented how people in his time were losing their houses, wives and even clothes to gambling. “By the time they are finished, they’re half of completely naked,” he wrote, “It’s shameless.” Efforts to crackdown on gambling have included penalties of 100 lashes and death and forced tenure in the army during the Tang Dynasty (618-907). The Song Dynasty Emperor Zhao Kuanggyin (960-976) ordered habitual gamblers to have their hands cut off. “The measure was very effective for quite some time,” historians noted.

Gambling is still technically illegal in China. It was one of the great social ills the Communists promised to eradicate. During the Maoist era gambling was not widely practiced in part because ordinary Chinese had so little money. Since the economic reforms, gambling has come back with a vengeance.

Illegal gambling revenues are estimated to be around $150 billion a year. By one estimate, some $600 billion is spent on illegal betting in China each year. By some estimates an equal amount flows out of China illegally each year on gambling. David Green of PricewaterhouseCoopers Macau told The Guardian, “My experience is that Chinese players prefer fixed-odds betting. They may be suspicious of animal racing, because it is essentially self-regulated ... casinos are regulated by the government, and depend principally on luck.”

The parking lot of the Beijing race track is filled with Mercedes Benzes, BMWs, Audis and Lexuses. Even though a banner across from the track reads "Resolutely Implement the Central Government's Order Forbidding Gambling," thousands line up behind computerized betting windows. The Chinese government signed a contract with Las Vegas contractor to build gambling casinos in an abandoned naval base near Macau.

Many Chinese see little difference between stock markets and casinos except that stock markets have a better rate of return. In the 90s the stock market became available and lottery tickets came out, and after 2000, a sports lottery appeared.See Stock Markets.

See Corruption

See Hainan Island.

Chinese Love of Gambling

Chinese gamblers from various countries are a mainstay of casinos in Las Vegas, Macau, Australia and many other parts of the world. One Hong Kong gambler told Sports Illustrated, "There's Chinese proverb: “A little knife can cut a big tree.' Chinese people don't want to bet one thousand dollars to make one thousand dollars. They want to bet one dollar to make one thousand dollars."

Hu Xingdou, an economics professor in Beijing, told the Los Angeles Times, “Gambling is a big part of Chinese human nature.” Tied to it are beliefs in superstition, numerology and a desire to get rich quick. “Chinese are the biggest gamblers in the world,” Hu said. “Thousands of years under an imperial system that tries to keep people down leads to a mentality of trying to become super rich overnight, preferably with out hard work.” Pent up desire to gamble has been released along with the economic reforms.

One Australian gambler in Hong Kong told teh Washinton Post, "people here seem to have a different attitude toward winning and losing than you and I. They take the rise and fall of fortune as a natural part of life. They love to bet. That's why its magic here."

A Chinese-American commentator wrote in 1888, "The Chinaman will gamble with his last cent...he will bet with toes if all conveniences are taken away." Bruce Edward Hall wrote in 1899, "To stop the Chinese from gambling would be like stopping the Chinese from eating."

In his 1907 book “John Chinaman at Home”, the Rev. E.J. Hardy wrote: "The Chinese are a nation of gamblers, and they begin the habit when very young...Your boy or servants bets as to whether you will order ham and eggs or fish for breakfast. A rickshaw coolie lays a wager on which shaft on his vehicle a fly will light on first, which is not more foolish than for British boys to bet on horses which they have never seen. The fly at least cannot be jockeyed."

Some of the images of Chinese as a race of gamblers is a stereotype. Explaining why the Chinese in Macau and Singapore "are not so gambling-mad" as those in Hong Kong, a respected magazine editor told the Washington Post, "the reasons for the level of betting here are social and economic rather than cultural."

Mah-jongg

Mah-jongg is the most popular game in China. It is played throughout Asia and by some groups of elderly Jewish ladies in the United States. Resembling dominoes, it is usually played with four people and a pair of dice and 136 heavy plastic tiles (plus eight optional tiles) with numbers, symbols and Chinese characters inscribed on them. The tiles make a very distinct sound when they are slapped on a table. All over China, you can hear this sound: Slap! Click! Pung! Chow! Mah-jongg!

Mah-jongg has been played in China for centuries. The name, a Chinese name for the mythical “bird of 1000 intelligence,” was given to it in the 1920s by an American oil executive, Joseph Babcock, who wrote some books about the game and introduced it to the United States, where it was quite popular for a while. Mah-jongg was banned in China during the Cultural Revolution. "if you wanted to play," one player told the Los Angeles Times, "you had to hide in a den like a criminal." The game is still banned at many universities even though it is one of the most popular Internet games.

Mah-jongg involves both luck and strategy. The rules and player goals are somewhat similar to those in Gin Rummy. Players draw and discard, trying to get combinations that score points. Different versions of the game are played in different places. The most popular version became popular in the city of Ningbo in the late 19th century.

The slapping of tiles can be so loud and incessant, and players can play the game for such long periods of time that some players lose their hearing. Hearing loss is such a problem that the Hong Kong government decided to cover employees of mah-jongg parlors with a fund used to compensate people for hearing loss in noisy occupations.

Tiles and Scoring in Mah-jongg

There are three suits in mah-jongg: Characters, Bamboos and Dots. Each suit has nine numbers. Each number has four tiles. This means there are 36 Characters, 36 Dots and 36 Bamboos, for a total of 108 suit tiles. There are also 28 honor tiles, comprised of 12 Dragon tiles (four tiles for each of three different colored dragons, red, green and white) and 16 Wind tiles (four tiles for each of the four wind directions)

There are three kinds of sets that players aim to get: 1) a chow, a sequence of three tiles of the same suit; 2) a pung, a three of a kind; 3) a kong, a four of a kind. Kongs are worth the most points. Chows are worth nothing at all. Extra points are scored for going out first. There are also ways to double and triple the score.

At the beginning of the game, each player starts with 2,000 points in counters. When a game is over each losing player has to give the winner his winning score in points from the counters. The losing players also have to give points to players that have more points than them. When gambling each point had has a monetary value.

Playing Mah-jongg

The object of the mah-jongg is to collect high-scoring tiles. The first person to a hold a complete hand — four sets and one pair — declares “mah-jongg!”

An elaborate ritual is used to select the seating arrangement. Once that is worked out all the tiles are turned face down and mixed up. Each player selects 34 tiles and stack them up in front of him without looking at them so each player has a wall in front of him composed of two rows of 17 tiles stacked on top of one another. The four walls are shoved together to form a sort of foundation. Another elaborate ritual is used to make an opening in the foundation.

Moving counterclockwise around the table, each player takes two pairs of tiles, until everyone has 12 tiles, and arranges them as they would with cards in a game of gun rummy. The players then take turns drawing new tiles and discarding old ones face up. The next player can take a face up tile or face down one. Play continues until one person declares “mah-jongg!”

Only the last discard can be picked up, and it can only be picked up if the player can it use for a pung or a chow. If this is the case he exposes all the tiles by laying them down next to the wall. This is known as the exposed hand. It scores less points than the concealed hand. It is possible to take a tile for a pung any time, and play continues with the next player.

There are other rules about declaring kongs, getting extra tiles, making kongs from pungs and determining what to do when someone declare mah-jongg.

Mah-jongg and Gambling

Mah-jongg and gambling go hand and hand. Explaining the link with gambling, one man told the Los Angeles Times, "There's got to be some money involved. Otherwise there's no fun." The game is also a convenient ways to pass a bribe. Businessmen often play with officials that always win.

Mah-jongg is widely played for money outside of China. Filipino president Estrada lost millions of dollars, gambling on mah-jongg. In Brisbane, 250 mah-jongg players dished out $10,000 each to enter a winner take all world championship mah-jongg tournament in which the champion went home with $1 million.

Many people play mah-jongg in legal and illegal mah-jongg parlors that are filled with smoking and cursing players, playing in tables packed closely to one another. Because of its association with gambling, mah-jongg has always been associated with prostitutes and opium dens.

Casino Gambling and China

Many Chinese gamblers and tourists go to casinos in Myanmar, North Korea, Russia, Laos, Vietnam and Macau, many of them near the Chinese border to cater to Chinese gamblers. Some admit Chinese only. Others are owned by Chinese and receive power and water from China. Casinos are illegal in China. By one count eight out of ten Chinese that visit China’s neighboring countries gamble. See Myanmar, North Korea, Russia and Macau, Places and Gambling.

Many Asian high rollers like to play baccarat.

Casinos in Las Vegas, Atlantic City, Australia, South Korea and the Philippines are actively trying to attract Chinese gamblers, particularly so-called “whales” who are known for wagering up to $100,000 on a single bet. Around 85 percent of the high rollers at Las Vegas are from Asia and increasingly from China. Chinese New Year is the biggest night of the year. The tables are laid out according to feng shui and Asian food is offered 24 hours a day.

Mark Six is a popular underground casino game in which players try to guess the numbers on colored ping pong balls pulled out of a transparent cylinder.

A favorite game among Chinese is baccarat. There are stories of high rollers and whales that bet $150,000 a hand at baccarat and play for 12 hours and lose $5 million in one sitting. Heaven-earth harmony is another popular Asian casino game in which a ping pong ball is dropped onto a grid with people betting in where it will land.

Macau’s Gambling Industry, A Window on China

In December 2011, the Economist reported: “Not far from China’s coast, Macau’s casinos buzz with the energy and abandon of the wildly wealthy. Marble columns, gold decor and money are everywhere. But behind the glittering facades there are signs of something darker...Macau’s success is not built purely on the Chinese love of gambling. It is also fuelled by a stampede of nervous money fleeing the mainland. A look behind the scenes at Macau reveals a lot about Chinese corruption, and also about how scared many Chinese businessfolk are about the political climate back home. [Source: The Economist, December 10, 2011]

Since 2004 when American casino operators first opened there, Macau has grown faster than a dealer sorts chips. Gaming revenues in the first 11 months of the year were 44 percent higher than in 2010; Macau is now four times bigger than Las Vegas. The former Portuguese colony, a “special administrative region” of China since 1999, is now the world’s gambling capital.

High-flyers who gamble with borrowed money in private rooms, known as VIPs, contributed around 72 percent of Macau’s $23.5 billion in revenues last year. Because gambling is illegal in mainland China, Macau is their destination of choice.

Macau’s Junket System

Macau’s idiosyncratic “junket” system helps to bring rich Chinese to Macau, The Economist reported. Junkets are middlemen who lend high-rollers money, arrange accommodation and are paid around 40 percent of the casinos’take in return. (In Las Vegas casinos carry out background checks on gamblers and lend to them directly.) [Source: The Economist, December 10, 2011]

Many have also started to worry about the junkets’health, partly out of concern about the stability of China’s “shadow lending” system. If rich Chinese saw their businesses collapse or property investments plunge, as some fret could happen if the mainland’s economy slows, the 200 or so junkets that operate in Macau could have trouble getting their money back from gamblers. At best there would be less money to lend. But junkets that could not collect debts might implode, leaving the casinos that had extended credit to them with big losses. Many casino executives do not seem to know how much money they have lent to junkets, which makes it hard to assess the possible extent of defaults.

Casino operators, like their customers, remain sanguine about future winnings. According to analysts, no big junket has reported any issues with bad loans so far. A casino executive said recently that he worried less about a junket going under than he did about the implication of a Macanese official in a corruption scandal or a murder at a casino. Any big crime would probably encourage China to intervene more heavily in Macau’s affairs and specifically in the gaming industry.

You can bet that the casinos want to avoid that. They are trying to attract more “mass-market” customers, who actually want to gamble for fun. Such people do not need loans to play and offer better margins, because casinos do not need to pay junkets a cut. A high-speed railway being built from Guangzhou to Macau will make it easier to lure them. Some casinos are also building venues with less floor space for blackjack and more for shops, theatres and restaurants. This may help placate the government in Beijing, which would rather see its citizens shop for jewellery than for a different currency. But as long as money feels nervous in China, it will seek a way out, and Macau is awfully convenient.

Laundering Money in Macau

Economist reported: It is not just a passion for cards that brought more than 13.2 million mainlanders to Macau in the first ten months of this year. Many come to elude China’s strict limits on the amount of yuan people can take out of the country. A government official who has embezzled state funds, for example, may arrange to gamble in Macau through a junket. When he arrives, his chips are waiting for him. When he cashes out, his winnings are paid in Hong Kong dollars, which he can stash in a bank in Hong Kong or take farther afield.

“There are many ways to launder money, more than we can think of,” says Davis Fong, an associate business professor at the University of Macau. Some bypass junkets and instead use pawnshops and other stores, where they buy an item with yuan and promptly sell it back for Macanese pataca or Hong Kong dollars — less, of course, a generous cut for the shopkeeper. No one can quantify how much money is laundered in Macau, but it’s “such an obscene amount of money you would die”, one resident avows.

The flow of money through Macau has caught the eye of the government in Beijing and may explain a temporary crackdown in 2008 on the number of Macau visas given to mainland Chinese. According to cables made public by WikiLeaks, an online troublemaker, others are also watching. A memo sent in December 2009 from the American consulate in Hong Kong to the secretary of state said that “[Macau’s] phenomenal success is based on a formula that facilitates if not encourages money laundering.” In a cable in 2008 Joseph Donovan, then the American consul-general in Hong Kong, wrote that “some of these mainlanders are betting with embezzled state money or proceeds from official corruption, and substantial portions of these funds are flowing on to organised crime groups in mainland China, if not Macau itself.”

Casino Gambling in Myanmar

The Los Angeles Times described a casino in Myanmar near the Chinese border that was housed in a warehouse-like building the size of two football fields and contained eight banks of roulette tables, rows of electronic blackjack machines and 12 pits for heaven-earth harmony. Buses and vans in nearby town of Ruili ferry customers to the casino. [Source: Mark Magnier, Los Angeles Times, April 25, 2005]

Describing the scene at this casino Mark Magnier wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “The mostly male clientele of the Ruili casino...placed bets through a haze of cigarette smoke. There was no alcohol and almost no small talk. A small crowd gathered as one winner collected thick stacks of bills totaling about $4000 and stuffed them into the sequined purse of his female companion....The gambling machines, chairs and tables were battered suggesting an operation than has been moved repeatedly.”

One Ruili resident told the Los Angeles Times, “When things get tough, we all go crazy moving everything from here to there. But if you have good connections you can stay in business even when the other are closed down.”

Cracking Down on Gambling

The government has shut down thousands of underground gambling parlors. In 2005, the Chinese government launched a campaign to crack down on gambling in China and urged neighboring countries to help out. A party cadre who lead the campaign told the press, “We’ve declared war on gambling. We must stop this illegal activity.”

The move was prompted by embarrassing revelations about party cadres losing large amounts of public money at foreign casinos and local officials gambling during work hours at local tea houses. One official in Jilin province lost $330,000 during 27 trips to North Korean casinos.

In 2005, there were 149 casinos across the border in Myanmar, Russia, North Korea, and Vietnam, most of them illegal. Under Chinese government campaign many were shut down. As of April there were only 28 left. In Some cases the supplies of water and power were cut off to the towns that hosted the casinos.

Thousands of underground betting parlors were shut down. Neighboring countries were told to close casinos at the border. A 24-hour hotline was set up to receive tips on illegal gambling operations. Hundreds of thousands of gamblers were questioned or temporally detained. Tens of thousands were arrested, with the majority of them being released after paying a fine.

Indeed many places were shut down but they reopened after the authorities left and the campaign was over. Well-connected gambling houses even welcomed the campaign because it helped get rid of competitors.

Many thought the crack down on gambling was absurd. Hu Xingdou, teh economic professor, told the Los Angeles Times, “Trying to ban it completely is just not going to happen. China also loses an incredible amount of money overseas every year.” By one estimate China lost $72 billion to foreign gambling in 2004, up from $48 billion in 1997. Hu has said it makes more sense to have some kind of regulated gambling in China to keep the money in the country.

Bringing Back Horse Racing in China

China’s only legal racecourse, Beijing Tongshu Jockey Club, opened in 2002. In 2004 it was home to 2,800 horses, of which about 900 actually raced. Located outside Beijing, it covers 395 acres and embraces two grass and one dirt track. The facility has seating for 40,000 but only drew around 100 people per day its first season and once had about 1,500 people. The owners hoped they would fare better when the gaming laws are changed.

As the law pertaining to horse racing stood in 2004, Chinese were not allowed to bet on horses but were allowed to “guess” which horse would win. Punters bought a “view-and-admire ticket” predicting an either odd or even numbered winner. Only members of the Jockey Club could bet and there were no bookies.

As of 2004, the track conducted races twice a week during the racing season with a handful of races each of those days. Punters complained that the returns were too low to make betting worthwhile. The track got around laws banning gambling because the government refered to teh horse races as an “intelligence contest” not gambling. In 2005, Tongshun was closed down by a court order after betters who lost money complained that gambling was taking place at the track.

In January 2008, the Chinese government announced the start of regular horse racing in the central city of Wuhan and said it was considering introducing betting on races there on an experimental basis in 2009. If the plan is approved it would mark the first time since the Communist Party took power in 1949 that real gambling on horse racing in China would be legal. Wuhan already has a “horse racing lottery.” Gambling is being introduced as a way to generate state revenues and create new jobs.

A test run of horse race betting was carried out in November 2008 at the China Speed Horse Open in Wuhan, signally a possible return of horse race gambling to China. Each spectator was allowed to place two bets for free, and winners were given lottery ticket that gave them a chance of winning small amounts of money.

Horse Racing in China

Both betting and racing were outlawed in 1949, and only riders and owners have been allowed to make money from the sport since it re-emerged in the 90s. But the authorities are reconsidering their ban on the “social evil”. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, November 29, 2008]

Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province, was historically a center for racing and is keen to regain that status. This autumn a commercial college in the city launched a three-year racing course which requires students to learn how to ride and to organize meetings as well as to study the theory of the sport. According to the Changjiang Daily, individuals and groups could now apply to join a racing club and buy shares in the horses, allowing them to make money from races. [Ibid]

There were some other horse tracks but they were closed down. A race course opened in Guangzhou in 1992 was closed down in 1999 and labeled an unsatisfactory experiment because authorities could not prevent people from placing bets on the horses. There are currently plans to open tracks in Hangzhou and Nanjing.

Some estimated that if real horse racing and betting were allowed it could create 3 million jobs and yield up to $60 billion in taxes. A survey by the Hubei Academy of Social Sciences found that 83 percent of Wuhan's residents thought introducing betting would have a positive social impact, while 51 percent were “interested” or “very interested” in gambling on the races. [Ibid]

Lotteries in China

Mainland China had two lotteries as of 2008. But most Chinese gamblers use illicit channels or head to the Happy Valley racecourse in Hong Kong or the casinos of Macau. Although they are part of China, the territories' special status means the mainland sees little of their vast profits.

There are large number of lottery games in China. Extremely popular, they are allowed to exist and thrive because they are not technically regarded as gambling because they money the raise is supposed to help a worthy cause. The laws are full of loop holes and there is no monitoring system. Many lotteries operate under the pretense of raising money for charity but most of profits goes into the pockets of those who run the lottery. Local governments usually get a cut and have few incentives to report irregularities.

In 1985, when lotteries were still forbidden CCTV aired a lottery-style program as part of its annual Chinese New Year show. Bingo-style lotteries were introduced in 1987. Later, scratch lottery tickets with small prizes of two to 1,000 yuan were popular. If players in one game got three symbols, they got a chance to a appear on a television game show and go for prizes up to 100,000 yuan.

In Chinese lotteries, 55 percent of the receipts go to the players and the rest is supposed to go to finance projects for the handicapped, elderly and people in need. Authorities outlawed the practice of giving away televisions and refrigerators because too many of the ones given away were defective and winners complained.

In 2000, the Chinese government introduced a national lottery as a way of generating revenues. Over 15 million tickets were sold in the first week. Jackpot winner received 1 million yuan (about $120,000) and losers kept their tickets for later drawings. Smaller prizes were also awarded. Most of the money earned from the lottery was supposed to be spent on social welfare programs for laid off workers, disabled people and retirees.

A soccer lottery pays $700,000 to people that can predicts the results of England’s Premier League and the Italian Series A games. It was launched partly to deter illegal betting on foreign soccer games.

There are illegal soccer gambling networks that can accessed using the Internet that take in billions of dollars. One run by a leader known as “Dark Brother,” is said to have taken in $14.7 billion dollars between 2006 and 2010 before it was shut down on the eve of the World Cup in 2010.

Obsession with Lotteries in China

People in all walks of life have become obsessed with lotteries. The head of a lottery research firm told the Los Angeles Times, “We found out at one county in Liaoning Province, the entire leadership was gambling and spent official meeting discussing what numbers to bet on.”

On people who play the lottery, Li Gang, an expert of gambling at Beijing Normal University, told the Los Angeles Times, “They have what we call the gambler’s fantasy. The cost of living in China has gone sky-high. Everyone wants to get rich. What is the fastest path to wealth? These people believed is lottery games.”

Some people steal large amounts of money to finance their lottery obsession. A 23-year-old bank teller falsified deposits orders for $2.8 million to fuel her boyfriend’s lottery addiction. A cashier at a hospital stole $140,00 in deposit money for patient care to buy lottery tickets for herself. Both were caught. The first got a seven year prison sentence. The second one got 14 years.

Lottery-Driven Bank Heist

In March and April 2007, two bank guards stole $6.7 million from a vault in a branch of the Agricultural Bank of China in Hebei Province they were supposed to be guarding and used most the money to buy losing lottery tickets. Their original plan was to “borrow” money from the vault, make a profit from the lottery using that money, and return the money before anyone noticed. The scheme didn’t work out as planned. The guards lost nearly all the money on the lottery, were caught and sentenced to death. The heist was one of the biggest in Chinese history.

The two guards were regarded as valued, reliable employees. They were the only ones with keys to the bank’s vault. First they took $26,000 to see if anyone would notice. No one did. One guard bought $16,000 of lottery tickets and won $13,000. Uncomfortable about what he had done he returned the money and made up the difference with his own money and swore never to take money again from the vault.

But within a few weeks the temptation of access to so much money proved to be impossible to resist. One of the guards later told the state media, “It was easy. We were the only two with keys, and they didn’t check how much money was in the vault every day. At the time, we didn’t think we were robbing the bank. We were going to return the money after we won big.”

After taking several million dollars and suffering a bad losing streak the guards felt they had no choice but to take as much money as they could and make a run for it. They loaded at least five large cash-filled safety deposit boxes in a van in broad daylight. When bank guards asked them what they were doing the gaurds said they were delivering money to a rich man who made a large withdrawal. When police broke into the vault a few days later they found a floor littered with lottery tickets. A nationwide manhunt was launched and they men were caught within a week.

Other Popular Chinese Gambling Games

“Fan tan”, or “pai gao”, was a gambling hall fixtures of the old days. It involved guessing the number of beans in a pot.

See Cricket Fighting, Unusual Sports

The Korean owners of the pachinko parlors in Japan are angry with Chinese youths who have figured out a way to use magnets on the slot machine versions of pachinko games to win ever time.

Image Sources: Louis Perrochon

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2011