LIU XIANG

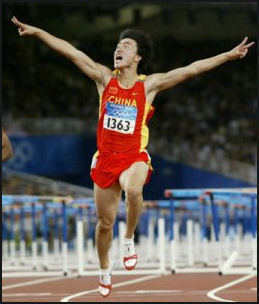

Liu Xiang Liu Xiang won the gold medal in 110 meter hurdles at the 2004 Summer Olympics. He was the first Chinese man to win an Olympic track and field gold medal. He achieved this milestone in stunning fashion at the age of 21 with a time of 12.91, equaling the world record, and became the first Asian and non-black to break 13 seconds in an event that he wasn’t supposed to win until 2008. Xiang is pronounced “sheeahang” meaning “to soar” in Chinese.

Dubbed “China’s Flying Man,” Liu is 6 foot 2, 180 pounds and is tangle of contradictions that reflect the contradictions found in capitalist, authoritarianism China. He is a multi-millionaire that often shares a dormitory apartment with his coach. In the view of many he is sexiest man in China yet he has no girlfriend. When the Olympic torch relay kicked off he was handed the Olympic torch by Chinese President Hu Jintao. Many Chinese find his blend of modesty and swagger appealing.

The Times of London described him as “a marketing dream with a conscience, he has no car, lives close to his parents and is a proud patriot. In a country coming to terms with the erosion of traditional values, he is a passport to the past.”

In China Liu’s gold medal is said to be “the heaviest” — an allusion to the fact it was the most significant one for the Chinese in 2004 and the one that carried the most weight. He carried the Chinese flag at the closing ceremonies and has been rewarded for his performance with endorsement deals with Nike, Visa, Yili milk, China Mobile and Coca-Cola. After he sang on television he was offered a $600,000 recording contract. The fact that he is tall (six foot two), handsome, and has an easy, slightly-cocky, self-assured demeanor, and has smartly styled hair hasn’t hurt his marketability

Liu is from Shanghai. He is a former high jumper who was directed to hurdles while he was in high school. Afer winning the Olympic gold in 2004 he said, “I think today the Chinese people showed the world they can run as fast as anybody else. I’m so happy I don’t even have the power to cry.” He beat the Olympic record set American Allen Johnson in 1996. Two years earlier Liu had asked Johnson for his autograph at a meet.

Liu also said “please pay attention to Chinese track and field. I think we Chinese can unleash a yellow tornado on the world.” Many Chinese believe that they are at a genetic disadvantage in sports such as track. There is no tradition of hurdling in China, no traditional sport similar to it and little understanding of its nuances and fine points.

Liu Xiang’s Early Life

The son of a water company employee who drove a truck and a pastry cook at a food factory, Liu was raised by his grandparents when he was young because his parents were too busy working. Liu weighed 9.9 pounds at birth which is extremely heavy for a Chinese baby. He was raised in a low-income area of Shanghai and said his greatest pleasure growing up there was eating his grandmother’s braised pork.

Liu was enrolled by his family in a district sports elementary school. Based on his bone structure, large feet and long Achilles tendon he was designated as a high jumper in the forth grade. He was good at age-group high jumping. At the age of 16, he matriculated to Shanghai No. 2 Sports School, one the city’s top training schools. He continued to train in the high jump there but didn’t make much progress.

At Shanghai No. 2 Sports School Liu spent five hours training and five hours doing academic work. He became one of the younger members of the school’s B team. Although he had talent he was hazed, beaten and relentlessly teased by older teammates, so much so his parents wanted to transfer him to a regular school. At this point coach Sun Haiping intervened. Sun was a renowned coach with a national reputation. He was coaching the school’s A team and convinced Liu’s family the teenager had talent and should stay at the school. Liu’s father later told the New York Times, “I trusted Sun. He was a responsible man and a famous coach.”

At that point Liu was promoted to the A team and Sun oversaw his training. Recalling the first time Liu tried the hurdles Sun told Sports Illustrated, “Most of the children were afraid of the hurdles, and would [slow down to] jump over them. Liu Xiang was not afraid of the hurdles. I was confident he could become the champion of Shanghai and run 13.5 seconds.” As Liu developed his competitive nature became apparent.

By the age of 18 Liu was dominating national competitions. At his first international meet he was awed by the muscles of the other competitors. But that didn’t stop his own performances from improving. In 2001, in just his third year of hurdling, Liu won the gold at the World University Games with a time of 13.33 seconds. Eight months later in July 2002 he ran a 13.12 at a meet in Lausanne, Switzerland, breaking the world junior record.

Liu Xiang and Hurdling

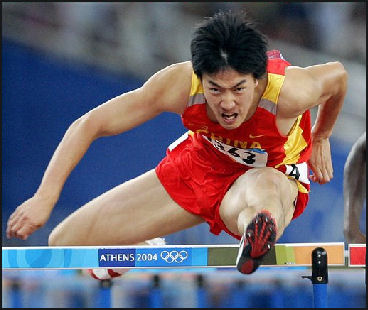

Liu lacks the speed of some of his rivals. He has run a 10.4 100 meters compared to a 10.04 for American hurdler Terrence Trammel. To make this deficiency he needs to have perfect form, which he does. He rarely chops his steps between hurdles.

Former 110-meter world record holder Renaldo Nehemiah told Sports Illustated, “The thing about Liu is that he can actually maximize the speed he has, without overstriding. Most guys have to take two and a half steps between hurdles; he takes a full three. And he is a fearless competitor. This a sport that has traditionally been dominate by North Americans, along with a few Cubans and Colin Jackson [of Great Britain]. And Liu Xiang is not afraid of anybody.”

At 6-foot-2, Liu is tall for a hurdler. He has a reputation for not making any mistakes, His start is one of his weaker points but once he get going he steadily builds speed and maintains his rhythm. He creates speed between the second and sixth hurdles and tries to maintain that speed until the end. In typical race Liu is lost in the group at the beginning of the race and emerges from the pack towards the end.

Liu Xiang’s Training

Liu usually trains in his hometown of Shanghai but trained in Beijing before the Olympics in 2008. There he worked out a dingy gym with other track athletes, doing the same callisthenics and drills — like with one with 20 kilograms on his shoulders — as the others, getting no special treatment, at least in the training sessions the media was allowed to see. When not training he relaxed playing ping pong, pool and bowling. But unlike the other track athletes, Liu was watched over by a seven-man team of coaches, doctors, drivers and gofers.

Liu is very close to his coach Sun Haiping. Sun has essentially been Liu’s guardian since he was teenager, When Liu was in Beijing he shared a two-bedroom apartment in a dormitory facility with Sun. In Shanghai they live in the same apartment complex and are said to live close enough to each other they can shout to each other out their windows.

Liu Xiang’s Lifestyle

Liu with Yao Ming at a Coke promotion Liu’s fame and sport regime leave him isolated. Most of his weekdays are spent inside Shanghai’s top training center, “I go home and I go to the training facility,” he said of his routine. “Two places, And those two places are the safest for me.”

Liu has said he doesn’t have time for a girl friend. His father hands out signed photographs to women that seek out the family apartment in Shanghai. He often can not get together with friends and thus keeps in touch with them by e-mail and text messages.

Liu is accompanied by coaches or officials almost wherever he goes, When he goes to a karaoke or a club he is taken there in a blacked-out car and is escorted in and sneaked out through back exits. The state limits his phone calls.

Liu reportedly likes shopping, eating Japanese food, singing karaoke and wearing designer clothes. He likes traveling abroad in part because he can do want he wants more freely and few people recognize him. Outwards signs of extravagance if they exist are not displayed. He bought an apartment in an old part of Shanghai and reportedly turned down a chance to live in Australia because he didn’t like the food.

Liu has said he doesn’t want to spend his whole life living as does. He has said he wants to try other things and excel in them. His love for his family is strong. He said, “one day I want to retire and then I want to look after my parents.” When he won the gold medal at the World University Games he rushed home so he could hang his medal around the neck of his grandmother, who was dying of cancer at the time.

Liu’s parents were given a new suburban apartment as a reward for Liu’s gold medal in Athens. Neither of them work at regular jobs anymore. His father’s boss has given his father unlimited time “to look after his son.” He conducts more interviews than Liu does.

Liu Xiang, Fame and Pressure

Liu is nicknamed the “The Yellow Bullet” and is a big celebrity in China. He often draws a crowd of shrieking young women and is mobbed by the press and fans wherever he goes. Before Beijing Liu was regarded as more famous than Yao Ming. In one survey of wishes for the Beijing Games, staging a successful Olympics was forth; Liu winning a gold medal was first.

Liu is adored like a pop star and admired for his individuality, a rare thing in China. Men want to be like him. Women want to marry him. In Lausanne, Switzerland, where Liu broke the hurdles world’s record there are women who want to marry him and a saying, “If you want to marry, then marry Liu Xiang.” A pair of golden shoes autographed by Liu Xang fetched $18,750 at a charity auction.

Johnson told the New York Times, “Sometimes when I talk to people and they ask me, 'How big is this guy in China?' I say, ‘Well, you know big Michael Jordan is or was in the United States. He’s bigger than that in China.' He is the athlete. The spotlight is going to be on him. He’s representing China. It’s going to be interesting to see how he handles it.”

Liu told the New York Times, “I am very peaceful at all competitions....Because for me, athletic competition is only part of life. I’m peaceful in my mind. The difference is all the people around me want me to stay depressed about all competitions but I’m not.”

Before the 2008 Olympics Liu told schoolchildren, “I am Liu Xiang. You are Liu Xiang, we are all Liu Xiang,” meaning were all are champions. One Chinese student told the New York Times, “He has the kind of spirit to fight for your dreams.”

In the run-up to the Olympics, at least five newspapers and one television station assigned reporters to cover him full time. In New York, Liu gave a large press conference in the Empire State Building lobby and smaller conferences on the observation deck.

Liu said, “I can only go places where very few people visit. Places that are very expensive.” If given a choice Liu said he woul prefer “to be ordinary and not so famous...I have money now, but I can’t shop.”

Liu has admitted he has difficulty sleeping and often confines himself to his hotel room. “Nowadays there is too much pressure. The others can hide but I’m No. 1 in the world...I’m expected to win the Olympics....Every time I go out there’s pressure on me. I don’t get good sleep.”

Liu Xiang’s Endorsements

Before the Beijing Olympics in 2008, Liu was visible on billboards and “Go for it China!” posters and in advertisements on television. He plugged Coca-Cola, Nike shoes and Lenovo laptops. He endorsed Cadillac cars even though he was not allowed to have a driver’s license. One Nike ad ends with him saying, “I am Liu Xiang, Who are you?” A marketing director at Coca-Cola told the New York Times, “He represents national pride, We want to celebrate that.”

According to one Chinese magazine Liu earned $8.75 million to $10.2 million in endorsements in 2007. Forbes said the figure was more than $23 million. An insurance company valued his legs at $13.5 million.

The government reportedly negotiated his endorsement and took half the money, with provincial and state federation taking 25 percent of his commercial earnings. His parents oversee his share.

Liu Xiang at World Championships

Liu was the bronze medalist at the World Championships in Paris in 2003 and silver medalist at the World Championships in Helsinki in 2005. These were the first track medals for a male Chinese at a track world championship.

Liu Xiang won his first World Championship gold medal in the 110 hurdles in Osaka in 2007. He had slow start and was behind most of the race but came on strong down the final stretch to defeat his rival Terrence Trammell of the United States by four hundredths of a second. Liu looked at Trammel as he approached the finish line. He said afterwards, “My start wasn’t great, maybe I was bit nervous or tired. After the last hurdle I couldn’t bear it any more so I looked around to see how fast the others were running. It wasn’t really intentional.”

Liu admitted that pressure was getting to him. “I have never been so nervous, even more nervous that the in the Athens Olympics...Too many people are watching me now. In Athens, I was little known. But I overcame all the pressure and tension and won the gold medal...Before the race I just stayed in my hotel room.” Liu followed up his Osaka performance with a disappointing third at the Golden Grand Prix meet in Shanghai. He said he was tired, hadn’t really been training and felt fortunate to pick up third.

In New York, Liu told students at Columbia University, “There’s nothing I can do about it. It’s only when an athlete sleeps that the pressure eases. What can I do about it? Can you tell me?

Liu Xiang Breaks the World’s Record

In July 2006, Liu set a new world record in the 110 meter hurdles, with a time of 12.88 seconds, at track meet on the Pontaise track in Lausanne, Switzerland. To celebrate he ran a victory lap without a shirt and climbed on a red metal clock that showed his winning time and clowned around and posed happily for photos. Afterwards he said “I can’t believe it, I can’t express it. I had a good start and after the first five hurdles it was a perfect race. I think I can still run even faster.” The previous record was first set by Britain’s Colin Jackson in August 1993 and equaled by Liu in 2004 at the Olympics.

A few weeks later in Shanghai Liu came within .2 second of breaking the record, before a crowd of 80,000 people. As was true in many races he started towards the back and finished strong, edging out his rival Allen Johnson.

As of 2007 Liu had three of the best times ever in the 110 meter hurdles. He attributes much of his success to his coach. In November 2006 he gave his coach a $200,000 apartment that he acquired through a sponsorship deal

Liu Xiang’s Olympic Victory and Racial Notions

Liu achievement was a slap in the face to naysayers that insisted that Asians would never be sprinters. Before Liu no Chinese had ever competed in an Olympic hurdles final before. Liu dedicated his Olympics victory to “all the yellow-skinned people” and called his performance a “miracle.” “Because I’m Chinese,” he said, “and have the physiology of the Asian race to me this is a miracle. But because of it I expect more miracles in the future.”

Among the biggest naysayers were the Chinese. An article in the People’s Daily a few days before his Olympic victory described how Asian athletes were best suited for skill sports like gymnastics, badminton and ping pong while “congenial shortcomings” and “genetic differences” kept them from competing as equals with blacks and whites in purely athletic events. Liu’s own coach attributed his victory to his technique and hard word not his ability.

In the 2004 Olympics Liu led from start to finish. “I just wanted to perform my best and raise my technique to the next level,” he said. “I was confident of finishing in the top three. The gold medal was beyond my expectations. It was an equally big surprise that I ran under 13 seconds....I hope the result today will change people’s minds about the Asian race in the sprints, that we’re no longer lagging behind the Europeans and Americans.”

Liu draped himself in the Chinese flag after his victory and carried the Chinese flag during the closing ceremony. “As soon as I got off the plane from Athens all the cameras were on me. All of the focus was on me.” On the plane home, Yao Ming told him, “Now you can understand the pressure on me.”

Liu Xiang Before the 2008 Beijing Olympics

Lui ran in only one indoor meet and five outdoor meets in the run up to the Olympics. Liu skipped the Gold League series in Europe in 2008 so he could focus on preparing for Beijing. In March 2008, he won the 60-meter hurdles at the world indoor championship in Valencia, Spain with a time of 7.46 second. Dayron Robles failed to advance beyond the heats when he stropped racing because he thought there was a false start. Liu had a slow start and didn’t take the lead until halfway though the race, On Robles he said, “I don’t know if I would have been the champion if he had also run, I feel a little lucky.” The five outdoor events were a meet in Osaka. Japan; the inaugurating event at the Bird’s Nest stadium in Beijing and three events in the United States .

Lui ran in only one indoor meet and five outdoor meets in the run up to the Olympics. Liu skipped the Gold League series in Europe in 2008 so he could focus on preparing for Beijing. In March 2008, he won the 60-meter hurdles at the world indoor championship in Valencia, Spain with a time of 7.46 second. Dayron Robles failed to advance beyond the heats when he stropped racing because he thought there was a false start. Liu had a slow start and didn’t take the lead until halfway though the race, On Robles he said, “I don’t know if I would have been the champion if he had also run, I feel a little lucky.” The five outdoor events were a meet in Osaka. Japan; the inaugurating event at the Bird’s Nest stadium in Beijing and three events in the United States .

In late May, Liu won the 110-meter hurdles at the inaugural meet for the Bird’s Nest stadium. A contingent of volunteers was assigned the task of keeping fans at a distance from Liu but the buzz surrounding his appearance was such the volunteers needed to be kept at distance. Before every heat a video of Lui’s Athens victory was show on the stadium’s large screen with the lead in calling him “China’s Flying Man” and fade out closing with “Can He Surpass Himself?” Crowds chanted, “”Liu Xiang, jia you! Liu Xiang, jia you” (“Liu Xiang, add fuel! Liu Xiang, add fuel!”) when he raced. After his event was over the fans left in droves even though many events were still left.

Liu didn’t compete after that. He suffered a hamstring injury in his right leg in May that forced him out of a the Reebox Grand Prix race in June in New York. He appeared at the Prefontaine Classic a week later in Eugene, Oregon but didn’t make it past the start as he was disqualified with a false start, which some think was intentional. That made him 0 for 2 in America — he entered two races but didn’t run in either of them. After that he didn’t race and trained in seclusion and only a handful of people knew what his condition was.

Twenty-one-year-old Cuban hurdler Dayron Robles threw down the gauntlet when he broke Liu’s world record by 0.01 of second with a time of 12:87 in June in Ostrava, Czech Republic. Some said that Liu avoided competing because he was intimidated by Robles, who competed in a number of events in Europe. Others said that Liu didn’t compete to avoid drug tests. His coach’s response to that was that Liu was tested 30 times in the first six months of 2008, sometime twice in two days.

Before the Olympics Liu’s’s coaches said that he hamstring had healed and he was ready to race. A week before th Olympics Liu said he ran a “12.90-something-“ — close or he former world record. Tickets for the events he was scheduled to appear in were going for 10 to 20 times their face value.

Expectations on Liu Xiang at the 2008 Beijing Olympics

pain An Internet poll before the Olympics found that the No. 1 wish among Chinese was for Liu to win a gold medal. For Liu, national pride was at stake plus a desire to show the world that China can excel at something other than “small ball” sports and diving and compete with the best in a sport usually won by Western athletes. The expectations placed on his shoulders were similar to those put on Cathy Freeman in Sydney in 2000 when she represented both Australia and the Aboriginal people. Freeman later said of Liu, “He is under more pressure than I was. I’m glad my career is over.”

After first trying to dismiss that there was any pressure on him Liu told Sports Illustrated, “I know the people in China want me to win my race very, very much. But I don’t want to think about what other people think. I just want to stay very relaxed and live a very normal life.”

Liu’s coach said, “Officials told us if Liu could not win a gold medal in Beijing, all of his previous achievement would become meaningless.” Zhang Min, a professor of international studies at the People’s University told the Washington Post, “Yao Ming is just famous, but nobody expects him to win a gold medal, Liu Xiang’s big breakthrough in track and field is not only for China, but all of East Asia...His win in Athens helped eliminate a deep inferiority complex in Chinese people’s hearts.”

United States track coach James Li told Sports Illustrated, “I really don’t think any athlete in any Olympic sport has experienced the kind of pressure that Liu Xiang is under. When you think about how big the country is, and how he is almost single-handedly carrying all of the hopes of the Chinese people, it really is unbelievable.” He said the Chinese don’t rally care about track so much. “They care because they think he’s going to be the winner...I really believe there is something in the national psyche that desires a winner. The country was so proud and then was beaten up by other world powers — [it] is almost like this one track meet would redeem the country. And that’s the pressure on Liu Xiang.”

The thing that people feared most was a positive drug test. Susan Brownwell, an expert on Chinese sport told the New York Times, “I think it would be really demoralizing to the Chinese people. If a drug test made it appear that he was not doing it with his biological gift, it would reaffirm feelings of racial inferiority.”

Liu Xiang's Withdrawal from the 2008 Beijing Olympics

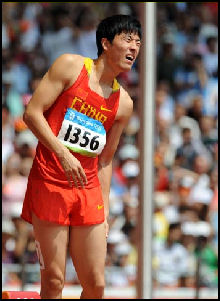

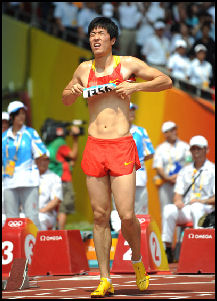

more pain Liu tragically was forced to drop of the 2008 Olympics without completing a single race because of an Achilles heal injury in his right foot. Liu was clearly in pain during his warm up, grimacing and limping after clearing just two hurdles, but he attempted to compete in his heat anyway. He started but gave up after writhing in agony from running a few strides after a false start.

After that Liu tore off the lane-designating stickers on his legs and walked off the track while the other runners returned to the blocks, causing great confusion at the Bird’s Nest. The stadium was dead quiet. All the spectators could see were the empty blocks and Liu leaving the stadium. For a time Liu sat below the stadium with his shirt pulled over his face in apparent shame and then disappeared. At the news conference Lui’s coach openly wept and said, “Liu Xiang will not withdraw unless the pain is intolerable, unless he has no other way.”

Washington Post columnist Tom Boswell called Liu the “saddest and most burdened man in Olympic history...now burdened under 1.3 billion bodies....At these Game, Liu is China...It is unlikely we will ever see an athlete in greater emotional pain, or a country that takes a loss more personally, or a caste of trainers and coaches who feel more devastated.” George Vessel wrote in the New York Times, “The sadness radiated outward to fans and officials and journalists, who immediately wept over the downfall of their national hero. All over China, people felt the collective sting of failure, concentrated on one athlete, which is always a risky business.”

Liu Xiang apologized to China, saying in a television interview, “There’s so many people concerned about me and who support me, I feel very sorry. But there’s really nothing I could do.” Liu looked tired and pale. He said, “I didn’t feel right when I was warming up before the race. I knew my foot would fail me. I felt painful when I was just jogging. I didn’t know why things turned out this way. I wanted to hang on. But I couldn’t. It was unbearable. If I had finished the race, I would have risked my tendon. I could not describe my feeling at that moment.”

National team coach Feng Shuyoan told Sports Illustrated, “When he entered the call room, he was telling himself that he had t go through with the race, He said he would only have made the decision to drop out as a last resort.” “His coach Sun said, “When Liu Xiang got to the warm up area, he was trying to endure; he was putting it out there for all he was worth” but “he couldn’t put any weight on his heel.”

Liu’s Achilles heel it turns out was literally his Achilles heel, specifically where the Achilles tendon attaches to the foot. A problem there had plagued him for years. His coach said the heel is on his take off foot and bears great pressure during the race. He had three doctors assigned to him but they could do nothing. The problem emerged a few days before, Feng said, “We didn’t realize it was so serious and would cause problems today.”

Liu’s problem was caused by bone spurs that have grown up between his Achilles tendon and ankle bone. He needed six months to a year to recover from the injury. According to a sports official, “Experts will come up with a solution package in roughly one month, and it will be handed over to the state sports bureau to make a decision.”

Reaction to Liu Xiang’s Withdrawal

withdrawal Chinese fans began leaving the Bird’s Nest stadium almost as soon as Liu left the track, some looking as if a love one had just died. A Chinese woman in h 60s told Sports Illustrated, “We were all looking forward to Liu Xiang winning the gold at the Olympics...It is the biggest letdown of the Olympics, but there is nothing we can do because it was an injury.”

Judging from Internet chatter and comments by Chinese who were interviewed, most people sympathetic rather than angry.. One fan quoted in the New York Times said, “I am sure he’s the one that regrets this the most, not anyone else. We feel disappointed, or course, but we still like him as a person.”

But some were suspicious and others were outright hostile, saying things he “stained the motherland” and should have crawled on his hand to finish the race. He was called a “runaway soldier” who committed a “cowardly act” and “hurt 1.3 billion people “a new world record” and was compared with a school teacher that ran from his classroom during the Sichuan earthquake, leaving his students behind. Some speculated that he withdrew because he knew he could not win and had already made a fortune.

Authorities ordered the news media not to criticize Liu or investigate the nature and severity of his problems. One person quoted in the Washington Post wrote on Tianya, China’s largest bulletin board: “Liu Xiang’s pull out is the beginning of China’s maturity. If people are naive enough to hope one person can support the dignity of the whole nation, then China is hopeless.”

China;s vice president Xi Jinping, widely seen as the successor to President Hu Jintao, sent a message that said “We all understand that Liu quit the race due to injury, We hope he will relax and focus on recovery. We hope that after he recovers, he will continue to train hard and struggle harder for national glory.”

Robles won the gold medal in Beijing. Chinese fans cheered enthusiastically for Chinese hurdler Shi Dengpeng but he failed to medal. Liu promised to return to competition. “I know I have the ability, once my foot has recovered, Now the most important thing is to heal my injury. I still have a chance next year, after all I’m still at the peak. I must be optimistic, and I should not blame everyone and everything nor myself. I will not easily give up.

Liu Xiang’s Surgery and Recovery After the 2008 Beijing Olympics

In December 2008, Liu underwent surgery on his right foot in Houston. He said, “I have consulted a number of specialists in China and abroad and based on their unanimous advice, I have taken this decision.” During the hour-long surgery, Liu had four small pieces of bone — ranging in size from a pea to a navy bean — removed from the Achilles tendon in his right foot. Dr. Thomas Clantain, who performed the procedure at Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center, said he expected Liu to run again, adding, “We felt he did very well through the surgery.”

In February 2009, Liu returned to China from the United States and resumed his training. His coach Sun Haiping said, Liu “was a top-level athlete before the injury, but now his training has been badly affected and it will be difficult to run those times again.” Liu himself said if he was injured again he would probably retire.

Liu was scheduled to make his return at the Shanghai Golden Grand Prix in September 2009. He did not compete at the World Track and Field Championship in Berlin in August.

In June 2009, Sun told Xinhua, “We feel satisfied about Liu’s recovery and the medical check revealed that his tendon is getting better bit it’s not enough yet, he still needs time before coming back to competition....There’s really no need to rush. Its premature to enter in competitions at this moment. We can count Liu in when he’s fully recovered. If he injures his leg again it will certainly end his career once and for all.”

Liu Xiang in 2009 and 2010

In October 2009, Liu Xiang won his third straight national title in the110-meter hurdles before 60,000 fans in Beijing with a time of 13.34 seconds, demonstrating that his recovery was going well. Afterwards he said, “I didn’t think it was possible to run a really good time. I just tried to run my own race.”

In December 2009, Liu won he 110-meter hurdles at the East Asian Games in Hong Kong. His time was a relatively slow 13.66. Afterwards he said, “I’m very happy to win the gold although the time was not great...I felt a bit tired because it’s the last race of the season, but I’m quite pleased with my performance.” He said increased competition would bring him back to form. It was his fifth race after getting surgery on his Achilles tendon. Liu’s time in September was 13.15, not so far off his best time of 12.88, when he placed second to American rival Terrence Trammell.

In April 2010, Liu pulled out of an event in Osaka, he said, so he could get ready for his showdown with Cuban rival Dayron Robles in Shanghai. But in that event Robles skipped out.

Liu competed at the Diamond League meet in Shanghai in May 2010 and finished the race with a time of 13.40, far behind his former world record time of 12.88. He said at the time he was still experiencing pain and inflamation in his injured ankle.

In Houston Liu underwent rehab under the guidance of Houston Rockets trainer Keith Jones.

In August 2010, Lui flew to Los Angeles for a check up in his foot. His father told AFP, “His ankle had been in intense pain since he intensified his training in June. He wants to know whether that level of pain is normal — then he can decide whether to continue at the current training intensity.”

Liu Xiang in 2011

His best time in 2010 was 13.09, well below his career best of 12.98.

Liu won the 110 meter hurdles at the Asian Games before a crowd of 80,000 at Aoti Main Stadium in Guangzhou. Over 600 million watched him on television.

In 2011 Liu began experimenting with a new start — in which he takes seven strides before the first hurdle instead of the normal eight — to shave several hundredths of a second off his times.

In February 2011, 27-year-old Liu finished a strong third with a time of 7.60 in the 60-meter hurdles at an indoor meet in Duesseldorf, finishing behind Czech Petr Svoboda and American Kevin Craddock who both finished in 7:42. Liu was happy with the result which was just 0.18 seconds off his personal best of 7.42. He said “I feel very good and I will be getting better. I already look forward to the world championships. I want to do really well there. Sixty meters is not my strength anyway because I am faster in the second part of the race.” A couple weeks later Liu was third gain, in Karlsruhe, Germany, with a time of 7.55.

In May 2011, Liu won the 110-meter hurdles at the Diamond League meet in Shanghai with a time of 13.07, the beast of the season up to that point. He beat American David Oliver, who had a streak of winning 18 finals going into the race. Liu’s new technique of seven opening steps seemed to have paid off as he beat Oliver, who had been unbeaten since August 2009, by a relatively comfortable margin. “It felt great,” he said. “This is my first outdoor race of the season. I reacted the fastest from the blocks and my seven-steps start worked very well for me. I am very satisfied with the time. I wasn’t quite expecting it but I do not think Oliver ran his best. I think he looked a little bit nervous. He was not very relaxed.” [New York Times- Reuters, May 16 2011]

In June 2011, Oliver avenged his loss the previous month to Liu Xiang at the Prefontaine Diamond League athletics meeting in Eugene Oregon. AFP reported: “Oliver won the 110 meters hurdles in a blazing 12.94 seconds. Oliver's time was the fastest in the world in this World Championships season, improving on the 13.07 previously posted by both Liu and Cuban Dayron Robles. [Source: Rebecca Bryan, AFP, June 4, 2011]

Liu led Oliver to the first hurdle by the barest of margins. But the big American had powered past by the third hurdle en route to a blistering early season time in a race run with a wind of 1.8m/sec. “I'm just happy for a good performance," said Oliver, adding that he knew from the opening strides that he was in a good rhythm. "I took care of business at the start — like I didn't do in Shanghai." Liu wasn't happy with technical flaws at the end of his race, but pronounced himself "very happy" with the time. "I feel very good for the timing," he said, but added: "Close to the finish my speed and power were not good." [Ibid]

Liu Xiang Takes a Silver at the 2011 World Track Championships in Daegu

Liu Xiang won a silver medal at the 2011 World Track Championships in Daegu in a very competitive race. Ken Marantz wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “The men's 110-meter hurdles lived up to its hype as one of the most anticipated events of the meet, but with an added twist of drama. American Jason Richardson came away with the gold medal after race-winner and world record-holder Dayron Robles of Cuba was disqualified for impeding China's Liu Xiang, who had to settle for the silver.

Richardson, who clocked 13.16, was officially declared the winner well past midnight after a Cuban appeal of the decision to disqualify Robles was turned down. Liu placed second in 13.27, while Britain's Andrew Turner was third in 13.44.

The race had featured a showdown of the three fastest hurdlers in history — Robles, Liu and American David Oliver, who struggled throughout the rounds and was edged by Turner at the line to finish out of the medals. "I wish it had been a drama-free race," Richardson said. "It is a bittersweet experience. It's never good when someone as talented as Dayron gets disqualified. But there are rules and we have to abide by them." Robles, the 2008 Beijing Olympics champion, was left still seeking his first world medal in three tries.

Liu Xiang Second in the 60-Meter Hurdles at the 2012 World Indoor Championship

Liu finished second to American Aries Merritt in the 60-meter hurdles at the world indoor championships in Istanbul in March 2012. AP reported: “When Aries Merritt shot out of the blocks to deny Liu Xiang victory in the 60-meter hurdles, he clinched more than just an unlikely victory. The American hurdler, who was thought to have little chance against the Chinese great, won the title and cemented a record gold medal haul for the U.S. team at the world indoor championships. [Source: AP, March 11, 2012]

Merritt set the pace in his final. Fastest out of the blocks, he even got the better of Liu, the 2004 Olympic champion who was trying out a new start with one step less to the first hurdle to keep the opposition at bay.When Liu saw the blur of Merritt, it immediately unsettled him. "I knew Aries Merritt is a fast starter," Liu said. "So I got out in a rush and was not able to control my technique."

In the absence of world champion Dayron Robles of Cuba, it should have been an easy victory for Liu but Merritt won in 7.44 seconds to push the favorite into second place 0.05 seconds behind. Frenchman Pascal Martinot-Lagarde won the bronze in 7.53.

Image Sources: 1) Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/; 2) Athletics Alberta; 3) Coca Cola; 4) AP, USA Today; 5) Liu Xiang Information; 6) Xinhua; 7) China.org ; 8) China Daily ; 9) SPorts Illustrated

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2012