CHINESE OLYMPIC TRAINING SYSTEM

When China set up its sports and athletics program it followed the Soviet model for athletic development, and established a system in which promising youngsters were selected at a young age and sent to special state-sponsored "boot-camp-style" training centers, where they endured rigorous training programs and were prepared for international competition. Scouts from various sports crisscross the country looking for athletes with proper physique and skills.

When China set up its sports and athletics program it followed the Soviet model for athletic development, and established a system in which promising youngsters were selected at a young age and sent to special state-sponsored "boot-camp-style" training centers, where they endured rigorous training programs and were prepared for international competition. Scouts from various sports crisscross the country looking for athletes with proper physique and skills.

China has spent hundreds of millions of dollars on sports academies, talent scouts, psychologists, foreign coaches and latest technology and science. China puts particular emphasis on developing programs in sports that have a lot events and give lots of medals such as shooting, gymnastics, swimming, rowing and track and field.

By the time of the 1988 Olympics in Seoul, China had spent an estimated $260 million to develop a national sports program. That year it won only five gold medals, yet many young athletes had entered the system who would do well in future Olympics. In 1992, China placed forth in the total medal count

In preparation for the Beijing Olympics more than 30,000 athletes are training full time, five times more than the number who will actually compete.

See Articles Under OLYMPICS factsanddetails.com ; Chinese Olympic Committee en.olympic.cn ; China’s Olympic History china.org.cn ; Book: “Olympic Dreams: China and Sports, 1895-2008" by Xu Gouqi

Chinese Olympic Training Facilities

Today, around 300,000 athletes, including 96 percent of China's national champions, are trained at China's 150 elite sports camps, like the Wuhan Institute of Physical Education and the Zheijiang Provincial Physical Education and Sports School in Hangzhou, and tens of thousands of smaller local training centers. The Haigen Sports Training Base in Kunming is the largest sports training camp in China. An additional 3,000 sports schools are responsible for identifying and nurturing talent.

The National Training Center is Beijing is comprised of a number of large buildings, some modern, some drab. Guards check the IDs of people entering the facility. Guards are posted outside each building. Olympic swimming hopefuls train at a military base in Guangzhou. Distance runners put in high altitude miles in restricted regions of Tibet.

The Shanghai Sports School, where Olympic-gold-medal-winning hurdler Liu Xiang trains, is comprised mostly of 20-year-old buildings that look 20 years older. Photos celebrating Liu’s world record are posted everywhere. A large sign read: BE POSITIVE, WORK HARD, CLIMB THE HIGH MOUNTAIN, WIN GLORY FOR THE COUNTRY.

Olympic Training Schools in China

In China there are more than 3,000 government-run sports schools, 20 major programs and 200 smaller programs. These schools and programs have produced nearly all of China’s Olympics athletes. About 400,000 students were enrolled in sports schools in 2005.

Only about one in eight of sports school students make it to a provincial team. Of these a third eventually make it to the national team and about a fifth of national team members become Olympians-in-training but only about one in eight of these actually make the cut to the Olympics. This means that for every 900 pre-teens who join the sports school system 899 never make it to the Olympics.

Wu Yigang, a professor at Shanghai University, told the Washington Post, the Chinese sports school system is “very good at finding sports talent. It meets the demand of our nation to make achievements in a very short time.” But on the other hand: “The Chinese way of training is problematic. These schools emphasize only training and neglect everything else...It greatly affects children’s knowledge and their moral outlook.”

Some schools stress only sports and can be viewed as little more than athlete-producing assembly lines. They often require six hours of training or more a day. Many Chinese athletes have devoted so much of their time to training they can’t read beyond the fifth grade level. Weifang City Sports School is comprised of a collection of moldy concrete buildings and gyms that smell of sweat and urine and dirt playing fields. Students sleep eight to a room on iron bunk beds and often collapses there, exhausted, during their brief afternoon break. The school has its own propaganda director and a bulletin board where students post self-criticism essays and is filled with slogans like “Learn from our Comrades and Create a New and Glorious Olympics.”

Other schools aim to produce more well-rounded athletes with academic as well as sports skills. The Qingdao Sport School in Shandong has a reputation for being particularly enlightened and modern. It has nice dorm rooms, coaches that understand the benefits of rest and a faculty that helps students get into university.

Zhabei-District Children’s Sports School in Shanghai produced four athletes that competed in Beijing in 2008, in table tennis, swimming and volleyball. It has 700 K-12 students and , state-of-the art sports facilities and coaches who were once elite athletes themselves. Zhabei is relatively strong in academics. It only requires 90 minutes of sports training a day

Olympic Recruiting Methods in China

Peter Hesseler wrote in the New Yorker: “The method of early recruitment is a product of China’s inability to provide every public school with coaches and sports facilities. The system has proved effective in low-participation, routine-based sports like gymnastics and diving.”

Olympic historian David Wallechinsky told the Washington Post, “They can mobilize their population of 1.3 billion people by reaching throughout the country and doing the German thing of looking for children of certain body types and going to their parents and getting them to send them to national training centers.”

In a typical city, every government district is asked to test and assess children from ages 8 to 13, and select candidates for sports schools. Children that show promise move on to bigger government training academies when they are teenagers.

Doctors measure height, arm span, bone density, flexibility and other things to predict what a child will be like in the future. X-rays and bone tests are used to determine bone density and structure and predict future growth.

Children demonstrating exceptional flexibility and balance are sent to gymnastics and diving camps. Tall children are sent to volleyball and basketball camps. Those with quick reflex are guided into ping pong. Kids with long arms are pushed into swimming or javelin throwing. Those with shorts arms make ideal weightlifters. Potential archers are picked on the basis of a test of steady nerves in which they are asked to spread their palm and stack as many .22 caliber bullets as they can on top of one another. Ideal candidates can stack eight or more bullets. Only those that can that can stack six or more are even looked at. Strong shoulders, superior vision and a cool demeanor are viewed as desirable attributes for archery.

Chinese Athletes Who Were Recruited

China-born, Los Angeles Times journalist Ni Ching Ching wrote: “When I was in the first grade, scouts from the Communist sports machinery came to our school to hunt for future champions. The event was diving. Never mind that I couldn’t swim and had no desire to be an athlete, I was told I had the right proportions and good feet. Chosen from a field of thousands to train at a state sports school, I was supposed to be thrilled to serve my country.”

Liu Huana, a player from the countryside who earned a place on China’s national women’s soccer team, told the Washington Post, “I had never heard of soccer until I was 13, when I moved to the county for my fifth-grade studies. One day people from the local athletic school came to our school to select new members. The teacher recommended me because I was the fastest runner in the class. I wore a skirt and sandal shoes that day, and I just took off my shoes and ran.”

Yao was sent to a full-time sports academy when he was 12. At that age he was already 6 foot, five inches. By measuring his knuckles sports officials predicted he would grow to 7 foot five inches and special attention was given to groom him to be a future star. Yao later said he didn’t even like playing the game until he 18 or 19. “My parents would probably prefer for me to go to college and play basketball only as a hobby.” To make sure he didn’t skip practice his coach went to his house and accompanied him to practice everyday.

Going to a Sports School in China

Many of the students in sports schools are recommended by coaches or are found by full-time scouts who travel the country looking for talent. Some are enrolled by their parents at cost of $100 a year. Some parents are motivated by ambition. Some just want a decent education for their children.

In the old days, parents were hard-strapped just to give their kids enough food to eat and rarely turned down an invitation for their kids to attend a sports school. But today there are many opportunities outside of sports and parents say they don’t want to limit their kids to just one thing and are not as gung ho about sending them to sports schools as they once were.

One 12-year-old who showed promise as a sprinter but turned down an opportunity to go to an elite sports school told the Washington Post: “My dad thinks as a primary school student my studies are still most important...I don’t want to either. I still prefer book studies. I feel athletic training is just for health.”

Parents of promising athletes who are poor are often given a home in their hometowns by the local sports bureau. Many Parents with kids at sports schools say they talk to their children rarely on the phone and when they do, their kids say little more than yes, no and okay, When asked about her family at the 2008 Games in Beijing, one diver said, “They didn’t come to watch the game. I don’t care about this.”

Chinese Athletes and Sports Schools

Students sleep on bunk beds in dormitory rooms. Between training sessions and classroom work they nap and rest in their rooms. Some students spend very little time on academics. One 15-year-old runner at Weifang City Sports school told Time she rarely cracked a book or even attended classes. When asked what she does, she said, “I run, and I sleep. That’s my day.”

Chen Yun, a 14-year-old daughter of a vegetable vendor in Shandong Province described in Time magazine, had never even heard of weightlifting when she was selected to train at Weifang City Sports School as a weightlifter based on measurements of her shoulder width, thigh length and waist size. When asked by Time what her favorite sport was, she said “weightlifting.” Her hobby? “Weightlifting.” When she started describing how she used to like to run in the fields around her village, the school’s propaganda director interrupted, and Chen said, “I prefer weightlifting now. I want t become a star athlete and make China proud.”

Olympic Training Methods in China

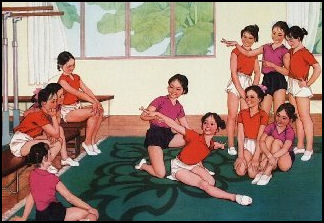

At the sports centers for young athletes, children are put through rigorous drills in old gyms on canvas mats in training sessions held several times a day throughout the day and sometimes into the night. The athletes rarely see their families. A coach at a sports camp where nine-year-old gymnasts worked out and lived 1,000 miles away from their homes told Newsweek, "A first they miss their parents. But they get used to it."

The first years of training often revolve around doing simple drills over and over and involve very little of doing the actual sport. Prospective archers, for example, spend the first year working on the release of the bowstring by repeatedly bending the bow as far back as they can, holding the position, often wincing in pain as they do, to strengthen their muscles.

Los Angeles Times journalist Ni Ching Ching wrote: “What I hated most about our training was the repetition. One drill was to jump from the end of the pool, feet first one hundred times facing the pool. One hundred times facing away. And another 100 times head first. Like piano scales, these were the basics of diving, We called them Popsicles, “bing quer”, because they required a tight, streamlined entry.

“I managed these robotic leaps from the sides of the pool, fudging the numbers as I went. But when the coach ordered us to do the same jumps from the 3-meter platform I showed my true colors...I was terrified of heights...I stood for an eternity on the diving board. The coaches were yelling. I couldn’t do it. With the weight of the world on me I closed my eyes and saw the end of my suffering. Instead of taking a leap of faith I literally stood my ground and crawled down the stairs.”

Gold-medal-wining weightlifter Liu Chunhing Liu was happy about her victory in 2008 and was also happy to have a break from her training. She told AP after winning the medal, “What I want the most at this moment is to spend some time with my parents. Since the last Olympics until now I have only spent six days with my parents.

Many athletes are fed special diets with special herbs and exotic Chinese medicines. Swimmers have been fed a concoction containing ginseng and deer horn while runners under the infamous coach Ma Junren were given an elixir made of fresh turtle blood.

In preparation for the 2008 Olympics, China’s gymnastics coaches were required to sign contracts promising not to let their athletes get injured before the Beijing games. The move came after star gymnast and Olympics champion Li Xiaoping was sidelined for a year because of an injury.

Olympic Training for Gifted Athletes in China

Yao Ming was regarded as such a lucky find he was watched nearly 24 hours a day and served meals in special kitchen “reserved for champions.” Yao joined the Shanghai Sharks when was 13. The training was tough. The Shark’s coach put him and the other players through four practices a day: The first at 6:30am, the last ending at 8:30pm.

Olympic gold medal diver Fu Mingxia entered the Beijing Sports School when she was nine. She told Time magazine that she cried out of homesickness for the first few months but found the training session emptied her of her emotions. "We don't have much time for other activities," she said, which for her were "listening to music, watching television and getting massages." She saw her parents only once a year and often was not allowed to see them when they attended her diving meets.

Players on the women’s soccer national team wake up at 7:30am and have two slices of bread with butter and an egg, sometimes with a little beef or vegetables. After a morning briefing practice begins at 10:00am and ends around noon, followed by a bath, a quick nap and lunch. After lunch there is another briefing and another practice session from 4:00pm to 6:00pm. Then its dinner and a session with massage therapists. There are many rules and regulations, including no cell phones or computers except for a short period in the evening. [Source: Washington Post]

At his sports school basketball player Yi Jianlian said, “I lived in a dorm with four or five guys and one bathroom. We had classwork from 8 to 11:30. I didn’t like classes. Basketball training was a lot of running and team-oriented drills. It was tough. The first time I did the 400-meter run I couldn’t finish. I was so upset I wanted to quit. If someone doesn’t perform there, they are asked to leave.”

Problems with Olympic Training Methods in China

The Chinese sports system is geared for creating a handful of top knotch athletes and discarding the rest. "It is really a factory system," U.S. diving coach told Newsweek. "They go through many, many young divers that don't make it to get those who do."

Sports Illustrated journalists in China said they found "evidence of every dubious Western sporting practice: free agency, bought-out contracts, cult-figure coaches, the use of performance-enhancing drugs, and squabbles over money." Winners at a competition observed in Shaanxi included imposters and ringers who should not have been allowed on the team. Fifty-four winners were found to have false papers and the closing ceremonies were concealed to save face.

Sports Illustrated came across an athletic “trade fair” that resembled a slave market: “Representatives of provincial sports commissions distributed catalogs listing some 1,300 homegrown athletes...Physical dimensions, achievements in competitions and an 'asking price' were listed for each athlete." [Source: Alexander Wolff, Sport Illustrated]

Problems Faced by Athletes They Leave Their Sports

Some former athletes get jobs as coaches or in sport associations. Some start their own businesses, selling sporting equipment or promoting athletic centers. But many have no skills and no more than an elementary school education and end up selling vegetables, laboring in factories, singing in bars or working as security guards. A local track-and-field coach told Newsweek, "When these kids leave athletic schools, they can't do anything, they have no skills. Local sports commissions sometimes provide jobs, but in the end, many become factory workers.”

About 6,000 professional athletes a year retire, About 40 percent of them have difficulty finding jobs. The cradle-to-grave system that used to take care of them no longer exists. Some athletes are promised job as policemen when they retire and these promises are often broken.

China Sports Daily estimates that 80 percent of China’s retired athletes suffer from unemployment, poverty or chronic health problems resulting from overtraining.

Many athletes that don’t make the grade find themselves out on the street without an education they would have gotten had they attended a regular school. The Los Angeles Times talked with a former national weightlifting champion who took a job scrubbing backs at a public bathhouse for ten cents a piece because she said it was the only job she could get. Her education stopped when she was in the third grade and she had no marketable skills. Another weightlifter, who won a gold medal at the Asian Games, could only get a job as a doorman at a sports school. . Former runner Ai Dongmei, who placed sixth in the Boston marathon, sold her medals and sells clothes on the street and runs a popcorn stand in Beijing with her husband, also an athlete, for a few dollars a day.

A surprising number of coaches, even ones who were Olympics champions, are chain smokers. The IOC is investigating reports in China of coaches beating child gymnasts and swimmers.

Decline of the Soviet-Style Training System in China

Reliance on Soviet-style training systems are declining somewhat. With the one-child population control policy the government has less control over the lives of promising athletes than they used to. Parents with only one or two children are less likely to turn them over to the state for training than parents with large families especially if they leave the sport centers without any job skills.

In its place, China is attempted to merge high-level sports and education much the way the N.C.A.A. does at universities in the United States. The efforts still has a long way to go. Most universities have uninspiring sports teams made up of athletes with skills much lower than those trained at the state-run sports schools.

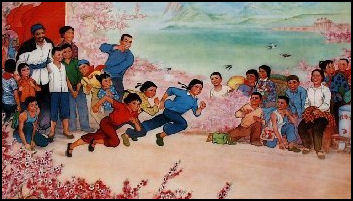

The sports programs for top athletes are less sinister than they are often made out to be. Athletes often spend as much time laughing and practicing dance routines as they do doing hard training. They are free to develop their own style and methods and are allowed to keep half their prize money and are given various bonuses for doing well. Some attribute China’s recent success to a retreat from traditional authoritarian methods.

Yu Fen, the coach of Olympic divers like Fu Mingxia and Huo Jing Jing, quit the national team in 1997 in part because of the poor treatment of athletes and the lack of job training. She started a new team at prestigious Tsinghua University in Beijing that mixes studying with athletics along the NCAA model and won public support for her cause when the national team stole her best divers.

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2010