CORMORANTS

Cormorants are waterbirds, whose name means "crows of the sea." A member of the pelican family, they can fly at speeds of 50mph and are particularly adept at swimming underwater, which is why they are such skilled fish catchers. They feed mostly on fish but also feed on crustaceans, frogs, tadpoles and insect larvae. Cormorants form same sex partnerships when they can not find opposite sex partners. [Source: Natural History, October 1998]

There are 42 species of cormorants and shags. They live mainly in tropical and temperate areas but have been found in polar waters. Some are solely saltwater birds. Some are solely freshwater birds. Some are both. Some nest in trees. Others nest on rock islands or cliff edges. In the wild they form some of the densest colonies of birds known. Their guano is collected and used as fertilizer.

Cormorants and shags (Phalacrocoracidae) comprises a single genus (Phalacrocorax) which some scientists divide into two genera (Phalacrocorax (cormorants) and Leucocarbo (shags). These birds are distributed worldwide, with the largest diversity in tropical and temperate zones, and inhabit marine and inland waters. They are found along marine coastlines of continents and islands. Inland populations inhabit lakes, open swamps and marshes, and rivers. They feed mainly on fish. Marine species feed primarily on fish (capelin, anchovy, herring, pilchard) although may take mollusks, crustaceans, cephalopods and polycheates. Inland diets include fish, frogs, aquatic insects, water snakes, and turtles. [Source: Laura Howard, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)

Cormorants and shags are medium to large birds (50-100 centimeters; .36 to 3.9 kilograms, 80-160 centimeters wingspan). Males are heavier and larger than females. Plumage in most species is iridescent black; some species have white on the head and underparts. During breeding the bare facial skin and gular pouch, eye-ring, bill and mouth lining become red, yellow, green or blue in color.

Cormorants and shags are similar-looking water birds, but they have several differences in size, build, and head shape. Cormorants are larger, heavier, reach one meter in length, while shags are smaller, more slender, and don’t exceed 80 centimeters. Cormorants have an angular, triangular head, flat forehead, a hick, sturdy, and hooked at the tip and green eyes surrounded by bare skin Shags have a smaller head, with a peaked forehead, a slender and delicate bill and emerald eyes surrounded by feathers. Cormorants have Brown-black feathers, a large white belly patch and no crest, except during the breeding season. Shags have black plumage with a green gloss and purple tinge to the wings, a light brown belly patch and a tufted crest on the head during breeding season. [Source: Google AI]

Cormorants belong to an order of waterbirds called Pelecaniformes. See Pelecaniformes Under PELICANS ioa.factsanddetails.com

ANIMALS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ;

INTERESTING BIRDS IN CHINA: CRANES, IBISES AND PEACOCKS factsanddetails.com

INTERESTING BIRDS IN JAPAN: SWANS, IMPALERS AND PHEASANTS factsanddetails.com

STELLER'S SEA EAGLES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

BLACKISTON’S FISH OWLS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, CONSERVATION factsanddetails.com

RED-CROWNED CRANES (JAPANESE CRANES): CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, ART, CULTURE factsanddetails.com

ENDANGERED BIRDS IN JAPAN: STORKS, ALBATROSSES, RAILS factsanddetails.com

CRESTED IBISES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, BACK FROM NEAR-EXTINCTION factsanddetails.com

CROWS AND PESKY BIRDS IN JAPAN factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Cormorant fishing Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; ; Photos of Cormorant fishing molon.de ; Rare Birds of China rarebirdsofchina.com ; Birds of China Checklist birdlist.org/china. ; China Birding Hotspots China Birding Hotspots China Bird.net China Bird.net ; Fat Birder Fat Birder . There are lots of good sites if you google “Birdwatching in China.” Cranes International Crane Foundation savingcranes.org; Animals Living National Treasures: China lntreasures.com/china ; Animal Info animalinfo.org ; Endangered Animals in China ifce.org/endanger ;Plants in China: Flora of China flora.huh.harvard.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Fishing with Cormorants” by Francis Henry Salvin Amazon.com; “The Cormorant Fishing Boat” by Douglas Brooks Amazon.com; “The Devil’s Cormorant: A Natural History” by Richard J. King Amazon.com; “A Field Guide to the Birds of China” by John MacKinnon and Karen Phillipps Amazon.com; “China Birds: A Folding Pocket Guide to Familiar Species” by James Kavanagh and Waterford Press Amazon.com; “Birds of China” (Pocket Photo Guides) by John Mackinnon and Nigel Hicks Amazon.com

Cormorants and Water

Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “Cormorants ride much lower in the water than do the ducks. Their bodies are half-submerged, with only their necks and heads sticking prominently out of the water. Every so often one of them disappears beneath the surface, only to pop up again a half minute or so later. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, December 2011]

As is always the case in the natural world, the cormorants' specialized underwater adaptations come with some severe trade-offs in other areas. Their legs, for example, are situated so far to the rear that they have great trouble walking around on land. Cormorants thus tend to spend most of their out-of-water time perched on rocks, pilings or tree branches. Also, their heavy bodies make liftoff difficult, and the big birds must taxi across the surface of the lake like a jumbo jet, building up speed before taking off.

When they are not in the water cormorants often rest on tree branches or other objects, sometimes resting with their wings spread full out. They often air out their feather under the sun when they rests on the ground or trees after they eat their full.In order to further decrease buoyancy and facilitate underwater swimming, cormorant feathers are designed to absorb water. Every so often, however, the feathers become too heavy and waterlogged, and the birds must come out and dry them in the sun and air.

Cormorant Swimming

The cormorant bio-design is created specifically for this lifestyle. The dense, heavy-set body minimizes buoyancy, making it easy to dive and swim underwater. Short but powerful legs, situated very near to the tail, are perfect for generating a strong forward thrust. Wide webbed feet also enhance the swim kick, and the long neck and long, hooked bill enable the birds to reach out and snare a fleeing fish.

Unlike most water birds, which have water resistant feathers, cormorants have feathers that are designed to get throughly wet. Their feathers don't trap air like water resistant varieties. This make it easier for them to dive and stay submerged while they chase fish. But this also means that their feathers become waterlogged. After spending time in the water cormorants spend considerable time on shore drying out. When they are out of the water they stretch out their wings to dry their feathers and look a little like wet dogs.

Cormorants can dive as deep as 80 feet and stay underwater for more than a minute. They have oil interwoven in their feathers that make them less buoyant than other birds and they swallow stones, which are lodged in their gut and act like a scuba diver's weight belt.

Cormorant Fish Catching Ability

Cormorants are highly specialized to a feeding style that ornithologists call underwater pursuit or pursuit-diving. When they dive from the surface they propel themselves through the water using their feet. Beneath the surface of the water, they actively chase after fish. Prey are captured in the bill. Upon returning to the surface, prey items are manipulated with the bill until the prey can be swallowed head first. Cormorants swallow fish whole and head first. They usually take a little time to shift the fish around to get it to go down their throat the right way. Bones, scales and other indigestible parts are regurgitated daily in a nasty goo.

Cormorant pursue fish underwater with their eyes open, their wings pressed against their bodies, kicking furiously with their legs and feet at the back end of their bodies. Richard Conniff wrote in Smithsonian magazine: "It swims underwater with its wings folded along its slender body, its long sinuous neck curving inquisitively from side to side, and its large eyes alert behind clear inner lids...Simultaneous thrusts of its webbed feet provide enough propulsion for a cormorant to tailgate a fish and catch it crosswise on its hooked bill...The cormorant generally brings a fish to surface after 10 to 20 seconds and flips it in the air to position it correctly and smooth down its spines.”

Cormorants may pursue prey alone or in groups (sometimes numbering in the thousands). Some species are cooperative foragers, with groups swimming together on the surface, moving in a coordinated fashion. They force the movements of fish schools and then dive in unison to capture fish. In the Brazilian Amazon, cormorants have been observed working as a team, splashing the water with their wings and driving fish into shallow water near the shore where they are easily collected. Neotropical cormorants plunge-dive (from the air) alone or in groups. Some species also join mixed-species foraging flocks. [Source: Laura Howard, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)

Cormorant Reproduction

Cormorants and shags are considered seasonally monogamous. Nest-sites and mates may change from year to year. Males choose a nest-site and try to attract females by waving their wings and pointing their bill skyward, exposing the skin of the throat. Males of some species rotate their heads backwards until the nape touches the rump. These displays end when a female lands beside the male with both of them engaging in greeting displays. The female defends the nest-site and builds the nest, while the male collects nest material. Making the nest generally takes takes one to five weeks. Copulation occurs at the nest-site. [Source: Laura Howard, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=\

Cormorants and shags breed in colonies ranging in size from a few to hundreds of thousands of pairs. According to Animal Diversity Web: Breeding is considered seasonal, although tropical species may breed year round. Nest-sites are variable, located on cliff ledges, ground, or trees. Some nests consist of sticks, seaweed, feathers, and grass cemented together with excreta. Ground nests are often depressions in soft substrates like sand or guano. Clutch size varies with species, ranging from two to six eggs. The egg-laying interval is two to three days. Eggs are pale blue or green. /=\

Parents take turns incubating eggs on foot webbing for about 24-31 days. Incubation stints are nearly equal in duration. Both parents take turns brooding and feeding chicks. Partially digested fish is taken from the parents' mouth. Fledging and independence generally occurs at 35-70 days. Eggs hatch asynchronously. Chicks are altricial and acquire a dark or white down within a week. Chicks are brooded and fed by parents. Fledging age is variable and ranges between 35-80 days.

Great Cormorants

Great cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo) are the birds used in cormorant fishing in China. Also known as the common cormorant and widely distributed in Asia and Europe and even found in North America, they are closely related to Japanese cormorants (Phalacrocorax capillatus). Some researchers place these two species as the only species in Phalacrocorax, with other cormorant species being placed in other genera.

Great cormorants are found in shallow, aquatic habitats, such as the coasts of oceans and large lakes and rivers. They range in weight from 2.6 to 3.7 kilograms (5.73 to 8.15 pounds) and range in length from 84 to 90 centimeters (33 to 35.4 inches). Their wingspan ranges from 1.3 to 1.6 meters(51.2to 63 inches).Males and females are similar in appearance, but males are five to 10 percent longer and up to 20 percent heavier. Both sexes have dark plumage overall, with a bluish gloss to it. Their wings are slightly more brown and their face and gular region are yellow, bordered with small, white feathers. Great cormorants vary in size and plumage throughout their range. In general, Asian and African populations are smaller than Palearctic and North American populations. [Source: Tanya Dewey, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Great cormorants live in rivers, lakes, reservoirs and bays. They dive quickly in water and catch fish with their bill and eat fish. They can be found in most places of China, often living in groups and nesting together. They seldom cry; but at the time when any disputes are raised in seeking a better place to rest, they would cry. Fishermen in Yunnan, Guangxi, Hunan and elsewhere still use common cormorants to catch fish for them. [Source: Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn]

Great Cormorant Behavior

Great cormorants are migrating birds but can also stay put in one area for a long time. They tend to go where the fish are. They catch fish alone or in groups in water. They nest in northern and central China and spend winter in districts in the southern China and the Yangtze River area. Large number of common cormorants reside and nest their young on Bird Island of Qinghai Lake. More than 10,000 common cormorants spend their winter in Mipu Natural Reserves of Hong Kong each year.

Great cormorants tend to leave roosts to hunt for prey early in the morning and return to their in less than an hour. They spend relatively little time foraging each day, although parents with young forage for longer. Large proportions of the day are spent resting and preening at roosts or near foraging areas. Great cormorants are awkward on land but are fast and agile swimmers. They rest with their neck in an S-shaped configuration. Like other cormorants, great cormorants do not fly long distances because their wing morphology is suited for fast flight over short distances. They fly at speeds of about 50 kilometers per hour or up to 93 kilometers per hour. [Source: Tanya Dewey, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Also like other cormorants, great cormorants are excellent swimmers, with wettable feathers and low buoyancy. Mean dive times have been recorded at 21 to 51 seconds, with dives in deeper water tending to take longer. They flap their wings and shake their bodies when emerging from the water and hold their wings in an outstretched position to dry their feathers. They may preen for up to 30 minutes, but do not seem to distribute oil from their oil glands onto their feathers. /=\

Great Cormorants in Japan

Kevin Short wrote in the Daily Yomiuri, “Great cormorants enjoy a cosmopolitan distribution, found across the Eurasian continent as well as Australia, Africa and the eastern coast of North America. Ornithologists divide the species into a half dozen or so subspecies, one of which (P.c. hanedae) is an East Asian form distributed from the Japanese islands south to Taiwan and on the southern part of the Korean Peninsula. [Source: Kevin Short, Daily Yomiuri, December 2011]

“Most species of cormorant are birds of the open ocean coast, but the great cormorant is a bit of a sissy, shunning heavy waves and swells and preferring to live in well-sheltered bays and coves, as well as on inland lakes and marshes. The Japanese name kawau means "river cormorant," and is used in contrast to Temmincks cormorant (P. filamentosus), which inhabits open coasts, and is called umiu, or "ocean cormorant.”

“Although most people assume that the kawau is used in traditional cormorant fishing, it is the umiu instead. Cormorant fishing (ukai), in which birds tethered to lines are used to catch ayu sweetfish, is usually accomplished in areas of fast current; to which the umiu, accustomed to swimming in rough water, is better suited.

“Like many birds that eat an exclusive fish diet, the great cormorants were once driven to the very brink of extinction. During the 1960s, both inland and coastal waters were heavily polluted by powerful insecticides and unregulated factory runoff containing dioxins and other poisons. These chemicals entered the food chain through algae and invertebrates, and were concentrated in the fish. Birds that ate the fish wound up receiving even heavier doses, leading in many cases to reproductive failure.

“Populations of great cormorants in Japan bottomed out in the early 1970s. All that remained were three colonies containing a few thousand birds. Since then, however, restrictions on hunting and vast improvements in water quality have allowed the cormorants to make an amazing comeback. Current estimates place their number at over 50,000. In some areas, such as Lake Biwa in Shiga Prefecture, the cormorants have recovered so well they now threaten the livelihoods of inland water fishermen. During the day, there are usually only a dozen or so cormorants on the lake. Come late afternoon, however, flocks of several dozen each begin arriving in tight V-formation, always from the northeast.

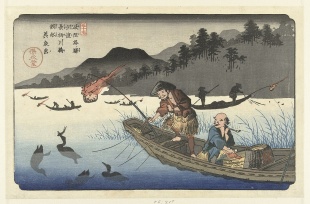

Cormorant Fishing

Described by Marco Polo and popularized in the children's story Ping, cormorant fishing is still practiced today in some parts of southern China and Japan, where it first evolved. The best time to view cormorant fishing is on a moonless night when the fish are attracted to lights or fires on the boats. Cormorant fishing boats can carry anywhere from one to 30 birds. On a good day a team of four cormorants can catch about 40 pounds of fish, which are often sold by the fisherman’s wife at the local market. The birds are usually given some fish from the day's catch after the day of fishing is over.

Cormorants fishing dates back at at least the 5th century in China. It has also been practiced on other places at different times. Tamed great cormorants were used for fishing in England and France in the 17th and 19th centuries. In most cases rings are placed around the cormorant's neck so that they can capture fish, but not swallow them. The birds are harnessed and a leash is used to bring them back, at which point the fish is removed from the throat. Some great cormorants have been reported to be so well trained as to not need the strap. They simply don't swallow the fish until the 8th fish, which they are allowed to eat. This suggests the potential that they can "count." Great cormorants with clipped wings have also been used on Djoran Lake (between Yugoslavia and Greece) to drive fish into nets. [Source: Tanya Dewey, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

The cormorants go through a routine of diving, catching fish, surfacing and having the fish taken out of their mouth by the fishermen. A piece of string or twine, a metal ring, a grass string, or a hemp or leather collar is placed around their necks to prevent them from swallowing their fish. The birds often have their wings clipped so they don’t fly away and have looped strings attached to their legs that allow them to be retrieved with a pole by the fisherman.

In China, cormorant fishing is done on Erhai Lake near Dali, Yunnan and near Guilin. In Japan it is done at night, except after a heavy rain or during a full moon, from May 11th to October 15th on the Nagaragawa River (near Gifu) and the Oze River in Seki and from June through September on the Kiso River (near Inuyama). It also done in Kyoto, Uji, Nagoya and a couple other places.

Cormorant Fishermen

Cormorant fisherman fish off row boats, motorized boats and bamboo rafts. They can fish day or night but usually don't fish on rainy days because the rain muddies the water and makes it difficult for the cormorants to see. On rainy days and extremely windy days, fishermen repair their boats and nets.

In a study of cormorant fishing, researchers found that cormorant fishermen were the least prosperous of three groups of fishermen. The wealthier group were families who owned large boats and owned large nets. Below them were fishermen who used poles with hundreds of hooks.

Some cormorant owners signal their birds with whistles, claps and shouts. Others affectionately stroke and nuzzle their birds as if they were dogs. Some feed the birds after every seven fish they catch (one researcher observed birds stopping after the seventh fish, which she concluded meant they count to seven). Other cormorant owners keep the rings on their birds all the time and feed them pieces of fish.

Fishing Cormorants

Chinese fisherman use great cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo) bred and raised in captivity. Japanese fisherman prefer Temmenick's cormorants (Phalacrocorax capillatus), which are caught in the wild on the southern shore of Honshu using decoys and sticks that bind instantly to the birds’ legs. Fishing cormorants usually catch small fish but they can gang up and catch larger fish. Groups of 20 or 30 birds have been observed catching carp that weigh more than 59 pounds. Some birds are taught to catch specific prey such as yellow eel, Japanese eel and even turtles.

Tanya Dewey wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Great cormorants eat almost exclusively fish less than 20 centimeters in length. They occasionally eat larger fish, up to 75 centimeters long or 1.5 kilograms. Fish are taken mostly in shallow water less than 20 meters deep, but they hunt throughout the water column, from the surface to the bottom, depending on the prey. They dive in and pursue fish under the water using vision, eating small fish underwater and bringing larger fish to the surface to swallow. Great cormorants may also follow fishing boats, taking fish discards or capturing prey disturbed by the wake of a boat. Great cormorants may forage alone or in flocks, varying regionally and possibly with subspecies. [Source: Tanya Dewey, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Great cormorants eat a wide variety of fish species, but may rely primarily on only a few species that are abundant locally, often bottom-dwelling species. In areas where cormorant species co-occur, they may pursue slightly different kinds of prey. In areas where great cormorants co-occur with double-crested cormorants, they eat more bottom-dwelling fish. Great cormorants will drink sea water and can rid themselves of excess salt through their salt glands. Adults bring chicks water when they are heat stressed. /=\

Cormorants can live to the age of 25. Some birds get injured and catch infections or die of hypothermia. The disease that Chinese fishermen fear the most is referred to as the plague. The birds usually lose their appetite, get very sick and there is nothing anyone can do. Some fishermen pray at temples; other seek the help of shaman. In some places dying birds are euthanized with 60-proof alcohol and buried in a wooden box.

Raising and Training Fishing Cormorants

Trained cormorants go for between $150 and $300 a piece. Untrained ones cost about $30 when they are six months old. For these fishermen carefully inspect the bird feet, beak and body to determine their swimming and fishing ability.

In the Guilin area fisherman use great cormorants caught in Shandong, a coastal province near Beijing. Captives females produce about eight to ten eggs incubated by brood hens. After the cormorants hatch they are feed eel blood and bean curd and pampered and kept warm.

Fishing cormorants reach maturity at age two. They are taught how to fish using a reward and punishment system in which food is given or withheld. They usually begin fishing when they are one year old.

Cormorant Fishing in Japan

Cormorant fishing is done at night, except after a heavy rain or during a full moon, from May 11th to October 15th on the Nagaragawa River (near Gifu) and the Oze River in Seki and from June through September on the Kiso River (near Inuyama). It also done in Kyoto, Uji, Nagoya and a couple other places.

The practice of cormorant fishing is over 1000 years old. These days it is performed mostly for the benefit of tourists. The ritual begins when a fire is set or a light is turned on over the water. This attracts swarms of trout-like fish called ayu. Tethered cormorants dive into the water and frantically swim around, gulping down fish.

Metal rings and placed around the bird's neck to keep them from swallowing the fish. When cormorants' gullets are full they are hauled aboard the boat, and the still-moving ayu are disgorged on to the deck. The birds are then given rewards of fish, and thrown back in the river to repeat the process.

The boats are manned by four man teams: a master at the bow, in traditional ceremonial headdress, who manages 12 birds, two assistants, who manage two birds each, and a forth man, who takes care of five decoys. To get close to the action you need to take a viewing excursion on a tourist boats, often illuminated with paper lanterns.

Fishermen wear black so the birds can’t see them, cover their heads for protection against sparks and wear a straw skirt to repel water. Pinewood is burned because it burns even on rainy days. On fishing days the cormorants are not fed all day so they are hungry at fishing time. The birds are all caught in the wild and trained. Some can catch 60 fish an hour. After the fishing, the fish are squeezed out of the necks of the birds. Many visitors find this cruel but the fishermen point out that captive birds live to be between 15 and 20 while those that live in the would rarely live beyond five.

See Separate Articles TRADITIONAL FISHING IN JAPAN: AMA DIVERS, ABALONE AND OCTOPUS POTS factsanddetails.com; NEAR NAGOYA: CHUBU, GIFU, INUYAMA, MEIJI-MURA factsanddetails.com

Descriptions of Cormorant Fishing

The earliest known reference to cormorant fishing comes from a Sui Dynasty (A.D. 581-618) chronicle. It read: "In Japan they suspend small rings from the necks of cormorants, and have them dive into the water to catch fish. In one day they can catch over a hundred." The first referenced in China was written by historian Tao Go (A.D. 902-970).

In 1321, Friar Oderic, a Franciscan monk who walked to China from Italy wearing a hair shirt and no shoes, gave the first detailed account by a Westerner of cormorant fishing: "He led me to a bridge, carrying in his arms with him certain dive-droppers or water-fowls [cormorants], bound to perches and about every one of their necks he tied a thread, lest they should eat the fish as fast as they took them,” Oderic wrote. "He loosened the dive-droppers from the pole, which presently went into the water, and within less than the space of one hour, caught as many fish as filled three baskets; which being full, my host untied the threads from about their necks, and entering the second time into the river they fed themselves with fish, and being satisfied, they returned and allowed themselves to be bound to their perches, as they were before."

Describing cormorant fishing by a man named Hunag in the Guilin area, an AP reporter wrote in 2001: at the front of a bamboo raft, "his four cackling cormorants huddle together, preening feathers with long beaks or stretching wings. When he finds a promising spot Hun sets a net around the raft, about 30 feet out to hem fish in...Hung jumps up and down a few times on the raft to break the bird's reverie. They snap to attention and jump into the water."

"Huang barks a command and the birds dive like arrows; they paddle furiously underwater chasing fish. Occasionally, fish jump up from the water, sometimes right over the raft, in their effort to escape....A minute or two elapses before cormorants's pointy heads and sleek necks bob up above the water. Some clutch fish. Some catch nothing. Hung plucks them from the water and onto his raft with his boat pole."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated February 2025