SAKER FALCONS

saker falcon

Saker falcons (Falco cherrug) are the second fastest bird in level flight after the white-throated needletail swift, capable of reaching 150 km/h (93 mph). They are the third fastest animals in the world overall after the peregrine falcon and the golden eagle, with all three species capable of executing high speed dives known as "stooping", approaching 300 km/h (190 mph). Arabs called them Hur ("Free-bird") and falconry using them has been practiced in the Arabian Peninsula since ancient times. Saker falcons are the national bird of the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, Oman and Yemen as well as Hungary and Mongolia. [Source: Wikipedia]

Sakers are slower than peregrine falcons but they can still fly at speeds to 150mph. However, they are regarded as the best hunters. They are masters of feints, fake maneuvers and quick strikes. They are able to fool their prey into heading the direction they want them to go. When alarmed saker let out a call that sounds like a cross between a whistle and a screech. Sakers spend their summers in Central Asia. In the winter they migrate to China, the Arab Gulf area and even Africa.

Sakers are close relatives of gyrfalcons. Wild ones feed on small hawks, striped hoopees, pigeons and choughs (crowlike birds) and small rodents. Describing a young male saker hunting a vole, Adele Conover wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “The falcon takes off from perch, and a quarter-mile away it drops down to grab a vole. The force of the impact hurls the vole into the air. The saker circles back to pick up the hapless rodent.”

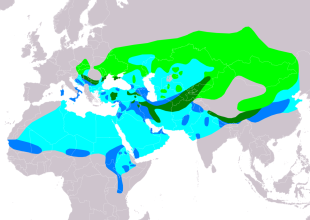

Saker falcons are often simply called “sakers”. They occur in semi-desert and forest regions from Eastern Europe across central Asia, where they are the dominant “desert falcon”, to Mongolia and China. Saker falcons migrate to northern South Asia, central China and northern Africa for the winter. In 1997, sakers were observed breeding as far west as Germany. Sakers occupy stick nests in trees, about 15 to 20 meters above the ground, in parklands and open forests at the edge of the tree line. No one has ever observed a saker falcons building their own nests; they generally occupy abandoned nests of other bird species, and sometimes even drive owners from their occupied nests. In the more rugged areas of their range, sakers have been known to use nests on cliff ledges, about eight to 50 meters above the base. [Source: Victoria Hekman, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Captive saker falcons tend to live longer than wild ones. The lifespan of saker falcon in the wild is typically five to seven years, with a high of 10 years. Their lifespan in captivity is typically 15 to 20 years, with a high of 25 years. Falcons used for hunting still experience many of the same causes of mortality as those in the wild, including several bacterial and viral diseases, parasites, bumblefoot disease, lead and ammonium chloride poisoning, and injuries incurred from impacting or struggling with prey.

Saker Falcons and Falconry

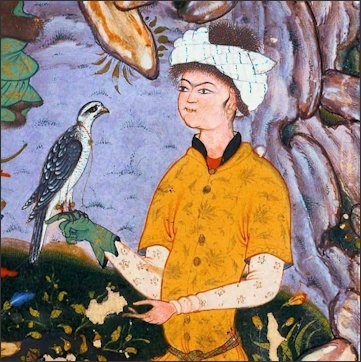

Mizra Ali

Saker falcons are among the most prized birds of prey in falconry. They were used by Mongol khans and regarded as descendants of the Huns who had them pictured on their shields. Genghis Khan kept 800 of them and 800 attendants to take care of them and demanded that 50 camel-loads of swans, a favored prey, be delivered every week. According to legend sakers alerted khans to the presence of poisonous snakes. Today they are sought after by Middle Eastern falconers who prize them for their aggression in hunting prey. [Source: Adele Conover, Smithsonian magazine]

Saker falcons are fast and powerful. They are effective against medium-sized to large-sized game bird species. They can reach speeds of 120 to 150 km/h and suddenly swoop down on their prey. But sakers often hunts by horizontal pursuit, rather than the peregrine's stoop from a height. Saker falcon and peregrine falcons have been hybridised to produce falcons used in the control of larger birds considered pests. However, In the Middle East many falconers release their sakers because it is difficult to care for them during the hot summer months, and many trained birds escape. [Source: Wikipedia]

Saker falcons are greatly loved and sought after by wealthy Arab falconers. A favorite hobby of wealthy businessmen and sheiks from the Persian Gulf is to fly to the deserts of Pakistan with their favorite falcons to hunt the lesser MacQueen's bustard, a hen-sized bird prized as a delicacy and an aphrodisiac which has been hunted extinction in the Middle East. Rare houbara bustard are also favored prey (See Birds). Winter is favorite time to hunt with sakers. Females are more sought after than males.

Victoria Hekman wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Sakers are very aggressive; one of the reasons they are so prized by falconers is that once they have decided upon a target prey, they are very persistent. They have been known to follow their prey into brush, and in the past (in the Middle East) they were used to harry and attack large game, such as gazelle, until the saluki hounds could catch up and finish the animal off. Sakers are patient, relentless hunters. They hover in the air or sit on their perch for hours watching for prey and fixing the exact location of their target, until suddenly diving for the kill. Females are almost always dominant over males. They sometimes try to steal prey from each other. /=\

Saker Falcon Characteristics and Diet

Saker falcons range in weight from .730 to 1.3 kilograms (1.6 to 2.9 pounds) and their wingspan ranges from one to 1.3 meters (3.3 to 4.3 feet). As is the case with other falcons, sakers have sharp, curved talons, used primarily for grasping prey, and a powerful, hooked beak able to sever their prey’s spinal column. Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Females are larger than males. The average length of males is 45 centimeters (17.7 inches); for females, 55 centimeters (21 inches). The average wingspan for males is 1.05 meters (3.4 feet); for female, 125 centimeters (4.2 feet). [Source: Victoria Hekman, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Sakers have a great variation in coloration and pattern, ranging from a fairly uniform chocolate brown to a cream or straw base with brown bars or streaks. Typically, sakers have white or pale spots on the inner webs of their tail feathers, rather than the bars of color that are common among other desert falcons. Their underwings are usually pale, and often have a translucent appearance when contrasted against the dark axillaries (clusters of feathers located in the "armpit" or axilla of the bird's wings) and primary feather tips. Arab falconers highly value ones with brown eyes and leucism (partial loss of pigmentation, resulting in white, pale, or patchy coloration of the skin, hair, feathers, or scales, but not the eyes).

Saker falcons are carnivores and have no known predators in the wild, except humans. They mainly feed on small mammals but also eat birds, amphibians, reptiles and insects. During the breeding season, they prey on primarily on ground squirrels, hamsters, jerboas, gerbils, hares, and pikas. These animals constitute make up 60 to 90 percent of a saker pair’s diet. At other times of the year, ground-dwelling birds such as quail, sandgrouse and pheasants, aerial birds such as ducks, herons, and even other raptors (owls, kestrels, and harriers) can account for 30 to 50 percent of all prey, especially in more forested areas. Sakers occasionally eat large lizards and are known to store and caches food.

Saker Falcon Behavior and Communication

Saker falcons are arboreal (live in trees), diurnal (active during the daytime), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), migratory (make seasonal movements between regions, such as between breeding and wintering grounds), solitary, territorial (defend an area within the home range). The size of their range territory is 16.18 to 93.22 square kilometers. [Source: Victoria Hekman, Animal Diversity Web(ADW) /=]

Victoria Hekman wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Sakers are not social birds; they prefer not to establish their nests close to other nesting pairs. Unfortunately, due to habitat destruction, sakers are being forced to nest closer and closer together, much more so than they ever would otherwise. However, in areas where food is plentiful, sakers will nest closer together than in areas where food is scarce. Space between pairs ranges from three to four pairs in three acres to pairs being six miles or more apart in the mountainous areas and steppes. The average spacing is one pair every 2.5 to 3.5 miles.

Sake falcons sense using vision, ultraviolet light, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smelling or smelling-like senses. They communicate with vision, touch and sound. They also employ duets (joint displays, usually between mates, and usually with highly-coordinated sounds) to communicate.

A female saker will make a “chip” noise to prompt her young to open their beaks for food, and they will chirp to get a parent’s attention. Male sakers call during their aerial displays in order to attract or impress a female, and if the female accepts the male, she may join in the calling at the end. Sakers may often call aggressively to drive off intruders from the nest or a freshly killed meal. /=\

Sakers, like other falcons, communicate fairly often by posturing. The most aggressive display is the Upright Threat; the bird stands up straight, spreads its wings and fluffs out its facial feathers, hisses, cackles, and strikes with the feet. This display is used by adult falcons in defense of the young, and by feathered nestlings against nest intruders. Sakers also use bowing to appease a mate, and communicate submission with a modified version of bowing, in which the beak is pointed to the side. /=\

Saker Falcon Mating and Reproduction

Saker falcons are monogamous (having one mate at a time) and breed once a year, in the springtime. Copulation may occur as often as several times a day for a period of four to eight weeks before any eggs are laid. The number of eggs laid each season ranges from two to six, with the average number being four. Sakers are generally two to three years old before they begin breeding. After the third egg is laid, full incubation begins, and usually lasts for about 32 to 36 days. [Source: Victoria Hekman, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

To attract females, male sakers engage in dramatic aerial displays, not unlike those of other members of the Falco genus. Male sakers soar over their territories, calling loudly. They end their display flights by landing on or near a suitable nesting site. During encounters with mates or potential mates, sakers bow to each other, and many interactions incorporate some sort of bowing. Males often feed their mates during the nesting period. When courting a prospective mate, males fly around, dangling prey from their talons, or bring it to the female in an attempt to prove that he is a good provider.

Sakers don’t make their own nests. They usually hijack the nest of birds, usually other birds of prey or ravens, often on top of boulders or small rises in the steppe or on power line towers or railroad check stations. If they encounter a large localized source of food, brood mates may remain together for some time./=\

Females reach sexual maturity about a year before males; they occasionally breed in their first year, but usually not until their second or third year, and some wait until their fourth year. Males, on the other hand, begin breeding in their second year at the very earliest; most wait until the third or fourth year, and some males don’t begin breeding until their fifth year. /=\

Saker Falcon Offspring and Parenting

The time to hatching for saker falcon young ranges from 32 to 36 days. They are altricial, meaning that young are born relatively underdeveloped and are unable to feed or care for themselves or move independently for a period of time after birth. Pre-weaning and pre-independence provisioning and protecting are provided by the male and the female. Chicks fledge between 45 to 50 days and become independent ay 65 to 85 days. There is an extended period of juvenile learning. The post-independence period is characterized by the association of offspring with their parents. Females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at one to four years, with the average being two to three years. Males reach sexual or reproductive maturity at two to five years, with the average being three to four years.[Source: Victoria Hekman, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Usually one or two birds are born. Young saker falcons hatch with their eyes closed, but they open them after a few days. In general, as is true for most falcons, male sake falcon offspring develop faster than females. Young sakers begin to fly at about 45 to 50 days of age, but remain within the nesting territory, dependent on their parents for food, for another 30 to 45 days, and occasionally longer. If young are threatened they stay still and play dead.

saker falcon at a bird rescue facility in North Carolina

Fifteen-day-old sakers are puffballs of feathers. They have two downy nestling plumages before attaining juvenile plumage. They attain adult plumage when a little over a year old, after their first annual molt. Young sakers stay close to their nest, occasionally hopping around nearby rocks, until they fledge. They hang around from 20 or 30 more days while the parents gently encourage them to leave. Sometimes siblings will remain together for a while after they leave the nest. Life is hard. About 75 percent of young sakers die in their first autumn or winter. If two birds are born the older one often eats the younger one.

While still in the nest, chicks chirps to get a parent’s attention if they are isolated, cold, or hungry. Females may make a soft “chip” noise to prompt their young to open their beaks to receive food. Mothers pass over chicks that are begging but have a mouth full of food to feed chicks that has not eaten enough. When a brood is well-fed, the chicks get along better than when food is more scarece. Well-fed chicks share food and explore their surroundings together after they start to fly. In contrast, poorly-fed chicks guard their food from one another, and may even try to steal food from their parents. If a chick dies and the rest of the brood is hungry, they will eat their dead sibling, but fratricide has never been observed. /=\

Saker Falcons, Humans and Conservation

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List sake falcon are listed as Vulnerable. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix II, which lists species not necessarily threatened with extinction now but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled. The population was estimated to be between 7,200 and 8,800 mature individuals in 2004. However, sakers live at low densities across large ranges in remote regions, making distribution status difficult to assess. The estimates of the number of sakers in Mongolia ranges from 1,000 to 20,000. A study in 1982 estimated there were about 100,000 pairs. [Source: Victoria Hekman, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

BirdLife International categorises sake falcons as endangered, due to a rapid population decline, particularly on the central Asian breeding grounds, where poaching the birds is common. There are also pressures from habitat loss and destruction and the use of pesticides and poisons (which contaminate their prey). Saker falcons are known to be very susceptible to avian influenza, individuals having been found infected with highly pathogenic H5N1 (in Saudi Arabia) and H7N7 (in Italy) strains.

According to Animal Diversity Web (ADW); The fact that female sakers, being larger, are preferred by falconers has led to a gender imbalance in wild populations, with males outnumbering females. In fact, about 90 percent of the almost 2,000 falcons trapped each year during the fall migration are females. Juveniles are easier to train than adults, so most of the trapped sakers are around one year old. Basically, the number of sakers taken each year probably does not have a significant impact on the species, but the preference for female sakers does.

In ancient times, saker falcons ranged from the forests of East Asia to the Carpathian Mountains in Hungary. Today the are only found only in Mongolia, China, Central Asia and Siberia. CITES bans the trade of gyr and peregrine falcons and severely restricts the export of sakers. According to the convention, Mongolia was allowed to export around 60 birds a year for $2,760 each in the 1990s. Separately, the Mongolian government made a contract with a Saudi prince in 1994 to supply him with 800 non-endangered falcons for two years for $2 million.

Alister Doyle of Reuters wrote: “Saker falcons are among those exploited to the brink of extinction. In the wild in Kazakhstan, for instance, one estimate was that there were just 100-400 pairs of Saker falcon left, down from 3,000-5,000 before the collapse of the Soviet Union. The UCR (www.savethefalcons.org), funded by public, private and corporate donors, wants Washington to impose limited trade sanctions on Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Kazakhstan and Mongolia for failing to stamp out the trade. [Source: Alister Doyle, Reuters, April 21, 2006]

Scientist and conservationist have worked hard to save saker falcons. In Mongolia, scientist have built nesting sites for sakers. Unfortunately these sites are often visited by poachers. Sakers have successfully bred in captivity in Kazakhstan and Wales.

Saker Falcon Smuggling

Ever since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the United Arab Emirates have been the main destination for thousands of falcons caught and sold illegally for hefty sums at the black market. Kazakhstan is estimated to lose up to 1,000 saker falcons per year. Saker falcons sell for up to $200,000 on the black market and have earned the name “feathered cocaine.” On the streets of Ulaanbaatar gentle-looking men sometimes approach foreigners and ask them if they want to buy young sake falcons. A typical bird sells around $2,000 to $5,000. Buyers prefer experienced hunters but sometimes buy young fledglings.

In Mongolia, there are stories of smugglers trying get sakers out of the country by dousing them with vodka to keep them quiet and hiding them in their coats. In 1999, a sheik from Bahrain was caught trying to smuggle 19 falcons through Cairo’s airport. A Syrian was caught at the Novosibirsk airport with 47 sakers hidden in boxes bound for the United Arab Emirates.

In 2006, Alister Doyle of Reuters wrote: “Smuggling is driving many species of falcon towards extinction in an illicit market where prized birds can sell for a million dollars each, an expert said. The black market in birds of prey, centred around the Middle East and Central Asia, can yield bigger profits than selling drugs or weapons, according to the U.S.-based Union for the Conservation of Raptors (UCR). "Imagine having something weighing 2 lb (1 kg) on your hand that can sell for a million dollars," UCR chief Alan Howell Parrot told Reuters of the most prized falcons. [Source: Alister Doyle, Reuters, April 21, 2006]

“He estimated smuggling of raptors peaked in 2001 with 14,000 birds, ranging from eagles to hawks. "The illicit trade has gone down dramatically, not because of law enforcement, but because the falcons don't exist any more," he said. Parrot said smugglers often skirted controls by travelling to falconry camps abroad with farmed birds. These, he said, were then freed, replaced with more valuable wild birds and re-imported. "You enter with 20 birds and leave with 20 — but they're not the same birds," he said. "The starting price is $20,000 and they can go for more than $1 million," he said. "Perhaps 90-95 percent of the trade is illicit."

“Another way to catch falcons was to attach a satellite transmitter to a wild bird and then release it -- hoping that it would eventually guide you to a nest and valuable eggs. He said farmed birds usually failed to learn how to hunt prey when released to the wild because captivity did not give harsh enough training. "It's the same with people. If you take someone from Manhattan and put them in Alaska or Siberia and they will be running around trying to dial 911," he said, referring to the U.S. emergency services phone number. "Only one in 10 farmed falcons can hunt well. You buy many and use the other nine as live bait to help catch wild falcons," he said.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, CNTO (China National Tourism Administration) David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, BBC, CNN, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated April 2025