BIRDS OF CENTRAL ASIA

Birds of prey do well on the steppes of Central Asia. They feed on rodents on other small mammals that thrive in the tussocky grass of the steppe. In Tashkent you can see magpies and swifts. There are also several crane species. Demoiselle cranes are known as the lovely birds by the people of Mongolia. They are smaller than most crane species and are among the most widespread, nesting across a wide swath of the Eurasian steppe. Demoiselle cranes reach altitudes of 24,000 feet when they cross the Hindu Kush mountains during their fall and spring migrations between nesting grounds in Central Asia and warmer, wintering areas in India. Demoiselle cranes winter in western Rajasthan.

Although nearly 500 bird species occur regularly in The Mountains of Central Asia Biodiversity Hotspot — which consists of two of Asia's major mountain ranges, the Pamir and the Tien Shan — none are endemic to the region. Many species belong to genera typical of the high ranges of Asia, such as redstarts (Phoenicurus), accentors (Prunella) and rosefinches (Carpodacus). Coniferous forests on the northern side of the Tien Shan form the southern limits of several boreal species, including the black grouse (Lyrurus tetrix) and northern hawk owl (Surnia ulula), while desert birds, including the great bustard (Otis tarda, VU) and houbara bustard (Chlamydotis undulate, VU) occur in the low-altitude zones. [Source: Conservation International, Critical Ecosysten Partnership Fund, CEPF,net]

The Mountains of Central Asia are an important stronghold for birds of prey, with important breeding populations of several species, including the golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), the imperial eagle (A. heliaca, VU), steppe eagle (A. rapax), booted eagle (Hieraaetus pennatus), lammergeier (Gypaetus barbatus), black vulture (Aegypius monachus), Eurasian griffon (Gyps fulvus), Himalayan griffon (G. himalayensis), peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus) and saker falcon (F. cherrug, EN).

Steppe Eagles

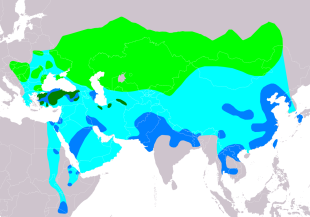

Steppe eaglesc (Aquila nipalensis) are a large bird of prey that breed in steppes of Eurasia and migrate to Africa and Southeast Asia in winter. Like all eagles, they belongs to the family Accipitridae. Their well-feathered legs place them in subfamily Aquilinae — "booted eagles". Steppe eagles were once considered to be closely related to sedentary tawny eagles (Aquila rapax). [Source: Wikipedia]

Steppe eagles are specialized predators of ground squirrels in their breeding area. They also take other small mammals and other prey, but do so more often when ground squirrels are less available. In the rather treeless areas of the steppe where they live steppe eagles tend to nest on a slight rises, often on or near an outcrop, but may even be found on flat, wide-open ground, in a rather flat nest. They are the only eagle to nest primarily on the ground. Usually one to three eggs are laid and, in successful nests, one to two young eagles fledge.

Steppe eagle engage in a large migration when nearly all the eagles in its entire breeding range move en masse to Africa and southern Asia. They use major migration flyways, especially those of the Middle East, Red Sea and the Himalayas. In its winter areasr the often engage in “sluggish and almost passive feeding” behavior — focusing on insect swarms, landfills, carrion and the semi-altricial young of assorted animals

The steppe eagle appears on the flag of Kazakhstan and is the national bird of both Kazakhstan and Egypt. There are estimated to be 53,000–86,000 remaining breeding pairs globally, with 43,000–59,000 pairs estimated in Kazakhstan, 2000–3000 estimated in Russia, 6000–13,000 estimated in Mongolia, and 2000–6000 estimated in China. One study projected the global number to be between 185,000 and 344,000 individuals at peak times, which is the end of the breeding season, with only 17,700–43,000 remaining adults.

See Separate Article: STEPPE EAGLES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Eastern Imperial Eagles

Eastern imperial eagles(Aquila heliaca) are one of the great birds of Central Asia. They have a body length of from 68 to 90 centimeters (27 to 35 inches) with a typical wingspan of 1.76 to 2.2 m (5 feet 9 inches to 7 feet 3 inches) and weighs 2.5 to 4.5 kilograms (5.5 to 10 pounds). They inhabit open plains, wooded steppes, semi-desert and foothills in Eurasia, the Middle East, North Africa and southern Asia. There are 10,000 breeding pairs worldwide. In 2011, the total estimated number of pairs was estimated at 3000-3500 in Russia and 3500-4000 in Kazakhstan, their last stronghold. The global population is small and declining due to persecution, loss of habitat and prey. They have been Listed as Vulnerable on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List since 1994. The numbers Eastern Imperial eagles declining due to loss of habitat, shooting and trapping and disturbance of breeding areas. [Source: Wikipedia]

Most population of eastern imperial eagles are migratory, breeding in Europe, Central Asia and Russia and wintering in northeastern Africa, the Middle East and South and East Asia Like all eagles, the eastern imperial eagles are members of the family Accipitridae; their feathered legs make them members of the subfamily Aquilinae. They resemble other a large, dark-colored eagle but are usually the darkest species in their its range.

Eastern imperial eagles are opportunistic predators that mostly feed on small mammals such as sousliks (ground squirrels), hamsters and hares. bur also eat birds, reptile and other prey types, including carrion. Compared to other Aquila eagles, they have has a strong preference for habitats at the interface between tall woods with plains and other open, relatively flat habitats, including the wooded mosaics of the steppe. Normally, nests are located in large, mature trees and the parents raise around one or two fledglings. After four yearly moults, young eagles attain the dark brown adult plumage with a pale crown and neck and white scapulars.

There’s a long Wikipedia article about Eastern imperial eagles en.wikipedia.org

Golden Eagles

Golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos) are the most widely distributed species of eagle. Like all eagles, they belong to the family Accipitridae and are one of the best-known birds of prey in the Northern Hemisphere, where they reside in both Eurasia and North America. Golden eagles are dark brown, with lighter golden-brown plumage on their napes. Immature eagles typically have white on the tail and often have white markings on the wings. Golden eagles use their agility and speed combined with powerful feet and large, sharp talons to hunt a variety of prey, mainly hares, rabbits, and marmots and other ground squirrels but also foxes. [Source: Wikipedia]

Golden eagles maintain home ranges or territories as large as 200 square kilometers (77 square mile). They build large nests on cliffs and other high places to which they may return for several breeding years. Most breeding activities take place in the spring; they are monogamous and may remain together for several years or possibly for life. Females lay up to four eggs, and then incubate them for six weeks. Typically, one or two young survive to fledge in about three months. These juvenile golden eagles usually attain full independence in the fall, after which they wander widely until establishing a territory for themselves in four to five years.

Golden eagles are generally found in open and semi-open habitats at elevations from sea level to 3600 meters (11,811 feet). They inhabit tundra, taiga, savannas, grasslands, shrublands, woodland-brushlands, coniferous forests, chaparral forests and mountains. They can also be found in marshes, other wetlands, suburban areas, agricultural fields and riparian and estuarine environments (wetlands adjacent to rivers and estuaries) Most golden eagles are found in mountainous areas,; they sometimes nest in wetland, riparian and estuarine habitats.

See Separate Article: GOLDEN EAGLES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Saker Falcons

saker falcon

Saker falcons are among the most prized birds of prey in falconry. They were used by Mongol khans and regarded as descendants of the Huns who had them pictured on their shields. Genghis Khan kept 800 of them and 800 attendants to take care of them and demanded that 50 camel-loads of swans, a favored prey, be delivered every week. According to legend sakers alerted khans to the presence of poisonous snakes. Today they are sought after by Middle Eastern falconers who prize them for their aggression in hunting prey. [Source: Adele Conover, Smithsonian magazine]

Sakers are slower than peregrine falcons but they can still fly at speeds to 150mph. However, they are regarded as the best hunters. They are masters of feints, fake maneuvers and quick strikes. They are able to fool their prey into heading the direction they want them to go. When alarmed saker let out a call that sounds like a cross between a whistle and a screech. Sakers spend their summers in Central Asia. In the winter they migrate to China, the Arab Gulf area and even Africa.

Sakers are close relatives of gyrfalcons. Wild ones feed on small hawks, striped hoopees, pigeons and choughs (crowlike birds) and small rodents. Describing a young male saker hunting a vole, Adele Conover wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “The falcon takes off from perch, and a quarter-mile away it drops down to grab a vole. The force of the impact hurls the vole into the air. The saker circles back to pick up the hapless rodent.”

See Separate Article: SAKER FALCONS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION factsanddetails.com

Pallas's Sandgrouses

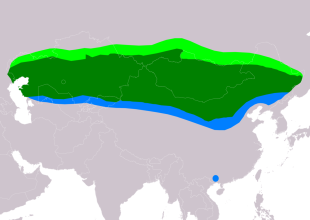

Pallas’s sandgrouses (Syrrhaptes paradoxus) are medium to large bird in the sandgrouse family. Native to central Asia, they have been declared the winners of the “snuggest underwear” prize for the thickness and coverage of the downy feathers beneath their decorative plumage. They are after the German zoologist Peter Simon Pallas (1741-1811) who has his name attacked to Pallas’s cats. Marco Polo mentioned a bird called Bargherlac (from Turkmen bağırlak) in The Travels of Marco Polo, published around 1300, that was probably a Pallas’s sandgrouse. [Source: Wikipedia]

Pallas's sandgrouses are 30 to 41 centimeters (12–16 inches) long with small, pigeon-like head and neck, but sturdy compact body. They have long pointed wings and tail and legs and toes are feathered. Their plumage is buff-coloured, barred above with a black belly patch and pale underwings. The black belly and pale underwing distinguish them the related Tibetan sandgrouse species. Male Pallas's sandgrouses are distinguished by their grey head and breast, orange face and grey breast band. Females have duller plumage and lacs the breast band though there is more barring on the upperparts.

Due to their primarily dry diet of seeds, these sandgrouses needs to drink lots of water. Their wing morphology allows them to fly flight with speeds up to 64 km/h (40 mph) having been recorded. Large flocks of several thousand individuals fly to watering holes at dawn and dusk making round trips of up to 121 kilometers (75 miles) per day. Male parents soak their breast plumage in water while drinking, allowing their chicks to drink from the absorbed moisture on their return.[

Houbara Bustard

There are the approximately 40,000 critically-endangered houbaras that remain in the wild. During their flamboyant courtship displays, male houbara puffs out the ornate feathers on his crest, chest and neck while making long, slow and graceful steps. Houbara chicks form a bond with their mother even while they are still in the egg, using calls to communicate. When migrating, houbaras can cover many hundreds of kilometers in a few days, travelling at steady speeds mainly by night. [Source: The Independent, November 9, 2022]

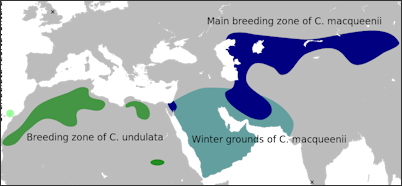

The Houbara bustard is a large bird that is found in semi-deserts and steppes in North Africa, the Middle East and Central Asia. They have black patches on their necks and wings and reach 65 to 78 centimeters in length and have a wingspan of up to five feet. Males weigh 1.8 to 3.2 kilograms. Females weigh 1.2 to 1.7 kilograms. [Source: Philip Seldon, Natural History, June 2001]

Houbara bustards are well suited for their environment. They are well camouflaged and do not need to drink (they get all the water they need from their food). Their diet is extremely varied. They eat lizards, insects, berries and green shoots and are preyed upon by foxes. Although they have strong wings and are capable fliers they prefer to walk partly, it seems, because they’re are so hard to see when they are on the ground.

range of the Houbara bustard

Bustards are long-legged, short-toed, broad-wing birds that live in the desert, grasslands of brushy plains of the Old World. Most of the 22 species are native to Africa. They usually are brown in color and duck when alarmed and are difficult to see. Males are generally much larger than females and they are famous for their bizarre courtship displays which often involve inflating sacs and elongating their neck feathers.

Male Houbara bustard are solitary during the nesting season. Females incubate the eggs and raise the young. Male Houbara bustard defend a large territory during the breeding season. They perform dramatic courtship displays with their crown feathers ruffled and white breast plumes sticking out and dances around doing a high-stepped trot. A mother usually raises two or three chicks, which stay with the mother for about three months even though they can fly short distances after a month. The mother teaches the chicks how to recognize dangers such as foxes.

Hunting Houbari

According to The Independent: Falconry is a tradition that goes back millennia in Arabic culture. It’s so significant it has been inscribed on the UNESCO List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Much has remained unchanged in the sport over its long history. The hunter is always a falcon, and the houbara has always held the dubious honour of being the quarry of choice. Said to have aphrodisiac qualities, it is prized for its meat. [Source: The Independent, November 9, 2022]

As long as hunting parties were small and the number of birds caught could be replenished, a balance was maintained. It is the huge increase in the scale of hunts that has left the houbara on the edge of extinction. Ahmed Boug, general director of terrestrial studies at Saudi Arabia’s National Center for Wildlife (NCW), says, “This activity has lasted for thousands of years, which means traditionally it was dealt with in a sustainable way. In the last decades, hunting has been carried out in an unsustainable way.”

With convoys of all-terrain vehicles now able to access areas that would once have been too remote or challenging to reach, and with flocks of falcons being flown each time, the number of birds killed per hunt has increased exponentially. Add to that habitat decline and an increase in the number of birds captured alive, in order to train falcons, the houbara is now classified as ‘vulnerable’ on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List.

Saving Endangered Houbara Bustard

Houbara bustard. numbers have been reduced by loss of habitat and hunting. Many Arabs love the taste of their meat and enjoy hunting them with falcons. Their fighting spirit and strong flight of the Houbara bustard makes them attractive targets for falconers. They are generally much larger than the falcons that attack them.

Houbara bustard

According to The Independent: Ironically, it may well be the houbara’s historical status as the falconer’s prey of choice that ultimately saves the species — no-one wants to see falconry or its main target disappear. In May 2019, the world’s first — and probably only ever — houbara museum opened in Saudi Arabia’s Al Qassim Park, a joint project from the International Fund for Houbara Conservation (IFHC) and Saudi Arabia’s Al Qassim Region. Aimed at highlighting the importance of protecting the species, it bears testimony to the cultural and environmental importance of the Asian houbara. [Source: The Independent, November 9, 2022]

In 1986, Saudi Arabia began a conservation program to save Houbara bustards. Large protected areas were established. Houbara bustards are captively bred at the National Wildlife Research Center in Taif, Saudi Arabia. Female bustards are artificially inseminated and the chicks are hand-raised and then released. The goal is to reestablish a healthy population in the wild. The main problems are preparing them to find food and escape predators.

After they are 30 to 45 days old, Houbara bustards are released into a special predator-free enclosure where they learn to find food. Once they are ready they can simply fly out of the enclosure into the desert. Many of the captively-raised birds have been killed by foxes. An effort has been made to trap the foxes and move them away but this did not decrease the death rate of the birds. Conservationists have more success with three-minute training sessions in which young caged bustards are exposed to a trained fox outside the cage. These birds had a higher survival rate than non-trained birds.

“It has been a challenge,” Boug, told The Independent: “Houbaras only have three or four chicks, not all of which survive. And you have to train the birds to return to the wild — because of all the time they’ve spent in captivity, they’re missing some of their natural behaviours.” They also face the threat of predators, with foxes particularly adept at picking off young chicks from the ground. And there’s the thorny issue of interbreeding with the migrant species that overwinter in Saudi. But persistence is slowly paying off. “Finally, we’ve succeeded in establishing a sustainable breeding population in the Mazhat az-Sayd reserve,” says Ahmed. The idea is that it’ll be the first of a network of protected sites across the Kingdom.He points to the NCW’s success in reintroducing other indigenous species as reasons to be cautiously optimistic about the houbara’s future. Red-necked ostriches, Nubian ibex and Arabian oryx now plod across the scrub of the Arabian Desert where just a few decades ago, there were none. Perhaps, in a few years, the houbara will join them.

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, U.S. government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated April 2025