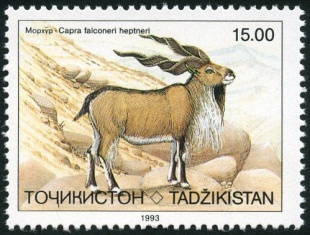

MARKHOR

Markhor ( Capra falconeri) are one of the largest wild goats. Residing primarily in Afghanistan and the western Himalayas, they lives in mountainous regions at medium and high elevations, from 700 to 4000 meters (2,300 to 13,123 feet) , eating tussock grass in the summer and shrubby leaves and twigs on lower slopes in winter. Its reddish coat is short and smooth in the summer and gets longer and grayer in the winter. Males have a long beard and long hair on the throat, chest and shanks. Females have smaller fringes of long hair. Both sexes have horns which spiral upwards and are smaller on females and can reach a length of 1.6 meters (5 feet) among males but are generally only 25 centimeters (9 inches) among females. Markhor are 1.6 to 1.7 meters (5.2 to 5.7 feet) in length, with an eight to 14 centimeter (3.2 to 5.5 inch) tail and weigh 80 to 110 kilograms (176 to 232 pounds). Females are smaller than males. Their lifespan in the wild is typically 11 to 13 years.

According to the IUCN: This species is found in northeastern Afghanistan, northern India (southwest Jammu and Kashmir), northern and central Pakistan, southern Tajikistan, southwestern Turkmenistan, and southern Uzbekistan. The species was classed by the IUCN as Endangered until 2015 when it was down listed to Near Threatened, as their numbers have increased in recent years by an estimated 20 percent for last decade. [Source: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, IUCN Red List of Endangered Species]

The colloquial name is thought by some to be derived from the Persian word mar, meaning snake, and khor, meaning "eater", which is sometimes interpreted to either represent the species' ability to kill snakes, or as a reference to its corkscrewing horns, which are somewhat reminiscent of coiling snakes. According to folklore, the markhor has the ability to kill a snake and eat it. Thereafter, while chewing the cud, a foam-like substance comes out of its mouth which drops on the ground and dries. This foam-like substance is sought after by the local people, who believe it is useful in extracting snake poison from snake bitten wounds. [Source: Wikipedia +]

The markhor is also known as Shakhawat. It is the national animal of Pakistan. Markhor marionettes are used in the Afghan puppet shows known as buz-baz. Local names include: 1) markhor (Persian, Urdu and Kashmiri); 2) margumay (Pashto); 3) rache (Ladaki) , rapoche (male) and rawache (female); 4) halden (Burushaski), haldin (male) and giri, giri Halden (female); 5) Boom Mayaro, (male) and Boom Mayari (female) (Shina); 6) rezkuh (Brahui), matt (male) and hit, harat (female); 7) pachin (Baluchi), sara (male) and buzkuhi (female); 8) youksh (Wakhi), ghashh (male) and moch (female); and : Shara (male) and maxhegh (female) (9) Khowar/Chitrali). +

Markhor Characteristics

Markhor range in weight from 32 to 110 kilograms (70.5 to 242.3 pounds) and have a head and body length that ranges from 1.4 to 1.8 meters (4.6 to to 5.9 feet). Their tail is 14 centimeters (5.5 inches) long. Markhor stand 65 to 115 centimeters (26 to 45 inches) at the shoulder, They have the highest maximum shoulder height among the species in the Capra (goat) genus, but are surpassed in length and weight by the Siberian ibex. .[Source: Nora Cothran, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. Ornamentation is different. Males weigh between 80 and 110 kilograms (176 and 231 pounds), whereas females weigh only 32 to 50 kilograms (70 to 110 pounds) Markhor males have longer hair on the chin, throat, chest and shanks. Females are redder in colour, with shorter hair, a short black beard, and are maneless. Both sexes have tightly curled, corkscrew-like horns, which sit close together at the head, but spread upwards toward the tips. The horns of males can grow up to 1.6 meters (5.3 feet) long, and up to 25 centimeters (10 inches) in females. The males have a pungent smell, which surpasses that of the domestic goat. [Source: Wikipedia +]

The coat of markhor is grizzled, light brown to black, and is smooth and short in summer, while growing longer and thicker in winter. The fur of the lower legs is black and white. Markhor differs from ibex in that they lack the extremely dense winter underwool possessed by the latter. Fringed beards are present in both sexes, but are thicker, longer, and more distinct in male markhors. Light and dark color patterns, typical of all Markhor subspecies, are present on the lower legs. Markhor lacks the knee tufts, inguinal and suborbital glands present in many species of goats inhabiting mountainous regions. [Source: Nora Cothran, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Although some might mistake Markhor for other members of the genus from a distance, the horns of markhors make them quite unique in appearance. Northern populations of Markhor can be easily distinguished from Capra aegagrus by the dorsal crest and lower hanging beard in Markhor, as well as the differences in horn morphology and coloration.

Markhor Behavior

Markhor are cursorial (with limbs adapted to running), diurnal (active during the daytime), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), migratory (make seasonal movements between regions, such as between breeding and wintering grounds), solitary, territorial (defend an area within the home range), social (associates with others of its species; forms social groups), and have dominance hierarchies (ranking systems or pecking orders among members of a long-term social group, where dominance status affects access to resources or mates). Population densities in Pakistan range from one to nine individualsper square kilometers. The range of such herds is often extremely limited as a result of the mountainous terrain which Markhors inhabit. [Source: Nora Cothran, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Females are social and travel in herds that contain, on average, eight to nine individuals. This is significantly smaller than the average herds of ibex and wild goats. . Herd composition is primarily female, with males temporarily joining during the rutting season. Ma;es are generally loners. Early in the season the males and females may be found together on the open grassy patches and clear slopes among the forest. During the summer, the males remain in the forest, while the females generally climb to the highest rocky ridges above. +

Markhor are adept and climbing and jumping on rocky terrain. They most active in the early morning and late afternoon hours. Markhors forage up to 12 or 14 hours per day, including a resting period to chew cud. Although most markhors move to lower elevations, and subsequently milder conditions, during the winter, several populations of Markhor have been documented at higher elevations.

Markhor sense and communicate with vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected by smelling. They have keen senses of vision and smell which serve them well in their relatively open and exposed habitat. Both senses are utilized in territory recognition and predator detection. Markhor continually scans its environment for the presence of predators. They exhibits highly calculated and intense movements in response to predator detection. Their alarm call closely resembles the bleating of domestic goats. During the birthing season, female markhors have been documented making a distinctive nasal call when approaching their young. Tactile communication is used in the rut when males compete with one another for mating access to females.

Markhor Diet and Feeding Habits

Markhor are herbivores (primarily eat plants or plants parts), folivores (eat leaves) and lignivores (eat wood). Among the plant foods they eat are leaves, wood, bark, and or stems. Typically they inhabit scrub forests made up primarily of oaks (Quercus ilex), pines (Pinus gerardiana), and junipers (Juniperus macropoda).

Markhor are mainly active in the early morning and late afternoon. Their diets shift seasonally: in the spring and summer they graze on grasses, but turn to browsing on leaves in winter, sometimes standing on their hind legs to reach high branches.

As is true of other large, mountain-dwelling ungulates, markhor maintains a strictly herbivorous diet. They eat a variety of grasses in the spring and summer and leaves, twigs, and shrubs in winter. Their diet includes Pennisetum orientale, Enneapogon persicum, Hippophae rhamnoides, and Quercus ilex.

According to the IUCN: “The species is typically found in areas with open woodlands, scrublands and light forests. In Pakistan and India these are made up primarily of Oaks (e.g. Quercus ilex), Pines (e.g. Pinus gerardiana), Junipers (e.g. Juniperus macropoda) and Deodar Cedar (Cedrus deodora) as well as Spruce (Picea smithiana) and Fir (Abies spectabilis, A. pindrow) in certain areas. In Tajikistan the vegetation in the lower parts consists of open woodland and shrub communities with Pistachio (Pistacia vera), Redbud (Cercis griffithii) and Almond (Amygdalus bucharica); with increasing elevation Juniper Trees (Juniperus seravschanica), (J. semiglobosa), mixed with shrubs of Maple (Acer regelii, A. turkestanicum), Rose (Rosa kokanica), Honeysuckle (Lonicera nummulariifolia) and Cotoneaster spp.. Markhor rarely use the high mountain zone above the tree line.” [Source: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, IUCN Red List of Endangered Species]

Markhor Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Markhor are polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time) and engage in seasonal breeding once a year during fall and winter. In the summer females gather in small groups with their newborn young. During the rut (mating season), normally solitary males temporarily join female herds and compete aggressively for the right to access the females in a herd. Males fight each other by lunging, locking horns and attempting to push each other off balance. The gestation period ranges from 4.5 to 5.67 months. The number of offspring ranges from one to two, with the average number being two. [Source: Nora Cothran, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=\; Wikipedia +]

Most of the parenting is done by females. The age in which they are weaned ranges from five to six months. During the pre-weaning stage provisioning and protecting are done by females. Pre-independence protection is provided by females. The post-independence period is characterized by the association of offspring with their parents. Young typically remain with their mother until breeding season six months after their birth although there are several reports of kids remaining with their mother after that. Young inherit the territory of their mother. Females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at 18 to 30 months. On average males reach sexual or reproductive maturity at 36 months.

Markhor young are usually born in May and June. They are initially born in a shallow earthen hollow. They are able to walk soon after birth, and can travel with the mother. Mothers provide nourishment is the form of milk and protect growing young. From predators. They stay with the mother for approximately six months,

Adult females and kids comprise most of the markhor population, with adult females making up 32 percent of the population and kids making up 31 percent. Adult males comprise 19 percent, while subadults (males aged 2–3 years) make up 12 percent, and yearlings (females aged 12–24 months) make up 9 percent of the population. +

Markhor and Goats

Some scientists have postulated that markhor are the ancestors of some breeds of domestic goat. The Angora goat has been regarded by some as a direct descendant of the Central Asian Markhor. Charles Darwin postulated that modern goats arose from crossbreeding markhor with wild goats. Evidence for Markhors crossbreeding with domestic goats has been found. One study suggested that 35.7 percent of captive Markhors in the analysis (ranging from three different zoos) had mitochondrial DNA from domestic goats. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Other scientist have put forth the possibility of markhor being the ancestor of some Egyptian goat breeds, due to their similar horns, though the lack of an anterior keel on the horns of the markhor belie any close relationship. The Changthangi domestic goat of Ladakh and Tibet may derive from the markhor. The Girgentana goat of Sicily is thought to have been bred from markhor, as is the Bilberry goat of Ireland. The Kashmiri feral herd of about 200 individuals on the Great Orme limestone headland of Wales are derived from a herd maintained at Windsor Great Park belonging to Queen Victoria. +

Fecal samples taken from Markhor and domestic goats indicate that there is a serious level of competition for food between the two species. The competition for food between herbivores is believed to have significantly reduced the standing crop of forage in the Himalaya-Karkoram-Hindukush ranges. Domestic livestock have an advantage over wild herbivores since the density of their herds often push their competitors out of the best grazing areas. Decreased forage availability has a negative effect on female fertility.

Markhor Subspecies

Seven distinct subspecies of markhor have been documented based shape, size, and curvature of the horns. Currently, only three subspecies of markhor are recognised by the IUCN: Astor markhor (Capra falconeri falconeri), Bukharan markhor (Capra falconeri heptneri) and Kabul markhor (Capra falconeri megaceros). The angle and direction of horn curvature varies among the seven subspecies of Markhor. Horn color varies from dark to reddish-brown

Astor markhor (Capra falconeri falconeri) has large, flat horns, branching out very widely, and then going up nearly straight with only a half turn. It is synonymous with Capra falconeri cashmiriensis or pir punjal markhor, which has heavy, flat horns, twisted like a corkscrew. Within Afghanistan, the Astor markhor is limited to the east in the high and mountainous monsoon forests of Laghman and Nuristan. In India, this subspecies is restricted to a portion of the Pir Panjal range in southwestern Jammu and Kashmir. Throughout this range, Astor markhor populations are scattered, starting east of the Banihal Pass (50 kilometers from the Chenab River) on the Jammu-Srinagar highway westward to the disputed border with Pakistan. Recent surveys indicate it still occurs in catchments of the Limber and Lachipora Rivers in the Jhelum Valley Forest Division, and around Shupiyan to the south of Srinagar. [Source: Wikipedia +]

In Pakistan, the Astor markhor there is restricted to the Indus and its tributaries, as well as to the Kunar (Chitral) River and its tributaries. Along the Indus, it inhabits both banks from Jalkot (Kohistan District) upstream to near the Tungas village (Baltistan), with Gakuch being its western limit up the Gilgit River, Chalt up the Hunza River, and the Parishing Valley up the Astore River. It has been said to occur on the right side of the Yasin Valley (Gilgit District), though this is unconfirmed. The flare-horned markhor is also found around Chitral and the border areas with Afghanistan, where it inhabits a number of valleys along the Kunar River (Chitral District), from Arandu on the west bank and Drosh on the east bank, up to Shoghor along the Lutkho River, and as far as Barenis along the Mastuj River. The largest population is currently found in Chitral National Park in Pakistan. +

Bukharan markhor formerly lived in most of the mountains stretching along the north banks of the Upper Amu Darya and the Pyanj Rivers from Turkmenistan to Tajikistan, but today only two to three scattered populations now occur in a greatly reduced distribution. It is limited to the region between lower Pyanj and the Vakhsh Rivers near Kulyab in Tajikistan (about 70”E and 37’40’ to 38”N), and in the Kugitangtau Range in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan (around 66’40’E and 37’30’N). This subspecies may possibly exist in the Darwaz Peninsula of northern Afghanistan near the border with Tajikistan. Before 1979, almost nothing was known of this subspecies or its distribution in Afghanistan, and no new information has been developed in Afghanistan since that time. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Kabul markhor (Capra falconeri megaceros) has horns with a slight corkscrew, as well as a twist. A junior synonym is Capra falconeri jerdoni. Until 1978, the Kabul markhor survived in Afghanistan only in the Kabul Gorge and the Kohe Safi area of Kapissa, and in some isolated pockets in between. It now lives the most inaccessible regions of its once wider range in the mountains of Kapissa and Kabul Provinces, after having been driven from its original habitat due to intensive hunting. In Pakistan, its present range consists only of small isolated areas in Baluchistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) province and in Dera Ghazi Khan District (Punjab Province). The KPK Forest Department considered that the areas of Mardan and Sheikh Buddin were still inhabited by the subspecies. At least 100 animals are thought to live on the Pakistani side of the Safed Koh range (Districts of Kurram and Khyber). +

Range of the Astor Markhor

Astor markhor (Capra falconeri falconeri) are also known as or flare-horned markhor. According to the IUCN:Astor markhor historically occurred in the eastern portion of Afghanistan in the high mountainous, monsoon forests of Laghman (headwaters of Alingar and Alishang Rivers); Kunar and Nuristan and is still extant at least in south central Nuristan. [Source: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, IUCN Red List of Endangered Species ==]

In India they are restricted to part of the Pir Panjal range in southwestern Jammu and Kashmir. Populations are scattered throughout this range, starting from just east of the Banihal pass (50 kilometers from the Chenab River) on the Jammu-Srinagar highway westward to the disputed border with Pakistan. Bhatnagar et al. 2009 observed Markhor only in Kajinag and Hirpura, and confirmed evidence of their occurrence in Boniyar and Poonch. In the areas of Shamsabari and Banihal Pass the taxon is likely extinct. ==

In Pakistan, a detailed study on the past and present distribution of “Kashmir” Markhor by Arshad (2011) showed that the area of occupancy and the number of locations have declined greatly (approx. 70 percent) during the 20th century. Flare-horned Markhor are mainly confined to the Indus and its tributaries, as well as to the valleys of the Kunar (Chitral) river and its tributaries. According to Schaller and Khan (1975), along the Indus River, Markhor inhabited both banks from Jalkot (District Kohistan) upstream to near the Tungas village (District Baltistan), with Gakuch being its western limit on the Gilgit River, Chalt and (Haraspo) Sikandarabad on the Hunza River, and the Parishing Valley on the Astor River. Currently, Markhor are known from various locations in the Diamer, Astor, Gilgit and Baltistan Districts. Markhor are found along the Nagar Hunza River from Sikandarabad downstream, in Naltar Valley, along the Gilgit River downstream from Singul and along the Indus River downstream from Basho to the provincial border with Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa. ==

Markhor are known to be present in the Juglot Ghooro, Rahimabad and Haramosh valleys in Central Karakoram National Park. The population in Haramosh was considered extinct by Arshad (2011), but since winter 2011 Markhor have been observed there, possibly indicating natural recolonization. The distribution range in Gilgit-Baltistan has been updated based on information from various sources. In Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, Flare-horned Markhor were found around Chitral and the border areas with Afghanistan where it inhabited valleys along the Kunar River (Chitral District), from Arandu on the west bank and Drosh on the east bank, up to Shoghor along the Lutkho River, and as far as Barenis along the Mastuj River. The distribution range in Chitral has been updated based on Arshad (2011), and includes side valleys of the Indus River upstream from Dubair, the Shishi River Valley as well as the Chitral River Valley and its tributaries upstream from Chitral up to Kaghozi Gol (Mastuj River Valley) and Shogore (Lutkho River Valley). ==

Range of the Bukharan Markhor

According to the IUCN: Bukharan Markhor (Capra falconeri heptneri) previously occupied most of the mountains lying along the banks of the Upper Amu Darya and the Pyanj Rivers from Turkmenistan to Tajikistan. Currently, it is found in only two or three scattered populations and its distribution has been greatly reduced. The subspecies was confirmed to occur as well in Afghanistan on the bank of the Pyanj River. [Source: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, IUCN Red List of Endangered Species ==]

In Afghanistan, reconnaissance surveys and interviews with villagers have shown that, across from the two strongholds of Markhor in Tajikistan, this subspecies exists but in very low numbers in the Darwaz Region of Badakhshan Province, and in Shahr-e Buzurg District and neighboring Chah Ab District of Takhar Province. The Markhor seem to cross the Pyanj River (which forms the border between Afghanistan and Tajikistan). ==

In Tajikistan, markhor are limited to the region along the Pyanj River east of Kulyab, southern Hazratishoh range, including the Kushvariston massif and the Pasi Parvor mountains, and the eastern slope of the southwestern edge of the Darvaz range). Formerly markhor were reported from the Babatag Mountains at the border with Uzbekistan and from the Sanglak and Sarsarak Ranges. No recent reliable information suggests that Markhor still exist in the Babatag. The presence of Markhor in the Sarsarak Range was confirmed in 2014, but the species has been extirpated from the Sanglak Mountains. ==

In Uzbekistan markhor are found in the Kugitang Range at the border with Turkmenistan. Its occurrence was reported in the middle of the 20th century from the Babatag Range at the border with Tajikistan. In Turkmenistan they are restricted to the western slope of the Kugitang Range, bordering Uzbekistan. ==

Range of the Kabul Markhor

Kabul Markhor (Capra falconeri megaceros) are also known as the Straight-horned markhor According to the IUCN: In Afghanistan, at least until 1978, they survived in the Kabul Gorge (Kabul Province) and the Kohe Safi area of Parwan Province, and possibly in some isolated pockets of Paktia Province. Intensive hunting pressure had forced it into the most inaccessible regions of its once wider range. No recent information is available on whether or not the subspecies is still extant in Afghanistan. [Source: International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, IUCN Red List of Endangered Species ==]

As for Pakistan, the most comprehensive study of the distribution and status of the Straight-horned Markhor was published by Schaller and Khan (1975). The study showed a huge past range for this subspecies, but the actual range in Pakistan at that time consisted only of small isolated areas in Baluchistan Province, a small area in the former Northwest Frontier Province (NWFP), and one unconfirmed occurrence in Dera Ghazi Khan District (Punjab Province). Virk (1991) summarized the information for Baluchistan Province, and confirmed the subspecies’ presence in the area of the Koh-i-Sulaiman (Zhob District) and the Takatu hills (Quetta District), both according to Ahmad (1989). ==

The presence of Straight-horned Markhor in the Torghar hills of the Toba Kakar range (Zhob District) has been repeatedly confirmed and it is possible that currently this area holds the only population consisting of more than 100 individuals of this subspecies. Qadir Shah et al. (2010) and Mazhar Liaqat (2013) confirmed the presence of straight-horned markhor in the Ziarat Mountains in Ziarat District of Baluchistan Province. The North-West Frontier Province (NWFP) Forest Department (1987, 1992) considered that the areas of Mardan and Sheikh Buddin were still inhabited by the subspecies. There is no recent information about the Safed Koh range (Kurram and Khyber Districts) where, according to Schaller and Khan (1975) probably at least 100 animals lived on the Pakistan side of the border with Afghanistan in the early 1970s. ==

Markhor Hunting

The markhor is a valued trophy hunting prize for its incredibly rare spiral horns which became a threat to their species. Trophy hunting is when rare species heads are hunted when the hunting is over the carcass is used as food. Foreign trophy hunters had a large demand for the markhor's impressively large horns as a trophy prize.

In British India, markhor were considered to be among the most challenging game species, due to the danger involved in stalking and pursuing them in high, mountainous terrain. According to Arthur Brinckman, in his The Rifle in Cashmere, "a man who is a good walker will never wish for any finer sport than ibex or markhoor shooting". Elliot Roosevelt wrote of how he shot two markhor in 1881, his first on 8 July, his second in 1 August. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Although it is illegal to hunt markhor in Afghanistan, they have been traditionally hunted in Nuristan and Laghman, and this may have intensified during the War in Afghanistan. In Pakistan, hunting markhor is illegal. However, recently, as part of a conservation process, expensive hunting licenses are available from the Pakistani government which allow for the hunting of old markhors which are no longer good for breeding purposes. +

During the 1960s and 1970s the markhor was severely threatened by both foreign trophy hunters and influential Pakistanis. It was not until the 1970s that Pakistan adopted a conservation legislation and developed three types of protected areas. Unfortunately all the measures taken to save the markhor were improperly implemented. The continuing declines of markhor populations finally caught the international community and became a concern. +

In India, it is illegal to hunt Markhor but they are poached for food and for their horns, which are thought to have medicinal properties. Markhor have also been successfully introduced to private game ranches in Texas. Unlike the auodad, blackbuck, nilgai, ibex, and axis deer, however, markhor have not escaped in sufficient numbers to establish free-range wild populations in Texas. +

Markhor Humans, Predators and Conservation

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List markhor have been listed since 1996 as Endangered, meaning it is in danger of facing extinction in the near future if conservation efforts are not maintained. On the US Federal List they are classified as Endangered. Since 1976, kabul (Markhor megaceros), straight-horned (Markhor jerdoni), and chithan markhor (Markhor chiltanensis), have been declared endangered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix I, which lists species that are the most endangered among CITES-listed animals and plants. [Source: Nora Cothran, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

There have been different estimates as to how many markhors exist but a global estimate put the number at less than 2,500 mature individuals. There are reservations in Tajikistan to protect the markhors. In 1973, two reservations were established. The Dashtijum Strict Reserve (also called the Zapovednik in Russian) offers markhor protect across 20,000 hectares. The Dashtijum Reserve (called the Zakasnik in Russian) covers 53,000 hectares. Though these reserves exist to protect and conserve the markhor population, the regulations are poorly enforced making poaching — as well as habitat destruction — common . [Source: Wikipedia +]

Poaching, hunting and habitat loss as reusult of livestock are the main threats to markhor. Humans hunt markhors, although they have been unable to penetrate several mountainous strongholds of markhor populations. Markhor is prized among trophy hunters and valued in traditional medicine. They are heavily hunted by humans during the winter months when the majority of markhors descends to lower elevations in search of forage. Markhor are relatively docile, but will quickly sprint away if they detect humans. Although the majority of the terrain in which markhors live is extremely arid and mountainous, they are facing competition from livestock, such as domestic goats and sheep.

Poaching — with its indirect impacts as disturbance and forcing markhor to habitats with lower quality food — threatens the survival of the markhor populations. Many poacher appear to be local inhabitants and state border guards, the latter usually relying on local hunting guides, and Afghans, illegally crossing the border. Poaching has caused the fragmentation of the population and distribution areas into small islands were the remaining subpopulations are prone to extinction. +

Markhor are preyed upon by lynx, leopards, snow leopards, bears, wolves and golden eagles. Although rare, documentation exists of golden eagles preying upon young markhors. Humans are the primary predators on markhor. Because markhor inhabit very steep and inaccessible mountainous habitat, several strongholds of markhor populations have been rarely approached by man. Markhor possess keen eyesight and a strong sense of smell to detect nearby predators. They are very aware of their surroundings and are on high alert for predators. They exhibit fast reaction and escape time to predators in exposed areas. +

Although markhors still face ongoing threats, recent studies have shown considerable success with regards to the conservation approach. The approach began in the 1900s when a local hunter was convinced by a hunting tourist to stop poaching markhors. The local hunter established a conservancy that inspired two other local organizations called Morkhur and Muhofiz. The two organizations expect that their conversations will not only protect, but allow them to sustainability use the markhor species. This approach has been very effective compared to the protect lands that lack enforcement and security. In India, markhor is fully protected (Schedule I) species under Jammu and Kashmir’s Wildlife (Protection) Act of 1978. +

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, U.S. government, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated April 2025