ASIAN WATER MONITORS

Asian Water monitors (Varanus salvator) are large lizards. They are is widely considered to be the second-largest lizard species after the Komodo dragon. Adults can have a body length of over 2.5 meters (8.2 feet, See Below). Asian water monitors can adapt to all kinds of environments, living in places near mountain streams and in tropical and sub-tropical areas. Their food can change based on their habitat. They can catch fish in water and can also climb on trees to seek food and eat frogs, snakes, birds, eggs of all kinds of birds, mice, insects and other small creatures.[Source: Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences, kepu.net.cn]

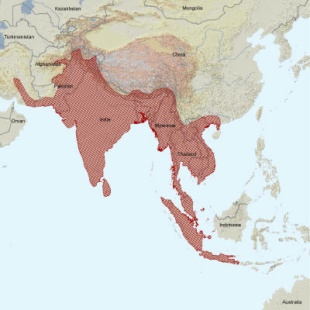

Asian water monitors occur throughout much of southern Asia, from India in the west to the Philippines in the east and the islands of Indonesia to the south. In China they can be found in South Yunnan, Guangdong, Guangxi and Hainan Island. Asian water monitors are semi-aquatic and are frequently seen on river banks, in swamps and in the water itslef. They have been known to cross large expanses of water, explaining their wide distribution. There are about a half dozen subspecies, many of them found primarily in one region, as well as a number of a former subspecies that were elevated to species.[Source: Doug Byers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

It is said that both Komodo dragons and the Asian water monitors are adept at finding, exhuming, and eating human corpses. A water monitor that measured 1.2 meters once consumed a snake that was 1.3 meters long. One that was two meters long consumed a turtle with a shell that was 16-x- 10.5 centimeters. /=\

Asian water monitors are not endangered and are fairly common despite the fact that their skins are used to make leather, dietary protein and traditional medicine. The annual trade in their skins may reach more than one million whole skins a year, mostly in Indonesia for the leather trade. Medium-sized individual are preferred because the skin of large animals is too tough and thick to shape. There is small trade in live monitors, but as a rule they don’t make very good pets.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List classifies them as a species of “Least Concern”. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix II, which lists species not necessarily threatened with extinction now but that may become so unless trade is closely controlled. Because of hunting and disruptions of their habitat Asian water monitors have suffered great losses. It has been suggested that water monitors are thriving in part because large females, who produce larger clutches, are avoided by the leather trade . /=\

RELATED ARTICLES:

MONITOR LIZARDS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, FOOD factsanddetails.com

GOANNAS (MONITOR LIZARD) SPECIES OF AUSTRALIA ioa.factsanddetails.com

MONITOR LIZARDS OF NEW GUINEA: SPECIES, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND REPRODUCTION ioa.factsanddetails.com

REPTILES: TAXONOMY, CHARACTERISTICS, THREATENED STATUS factsanddetails.com

LIZARDS: CHARACTERISTICS, SENSES, ODDITIES factsanddetails.com

KOMODO DRAGONS: CHARACTERISTICS, HABITAT, SENSES, MOVEMENT factsanddetails.com

KOMODO DRAGON BEHAVIOR: FIGHTING, REPRODUCTION, JUVENILES factsanddetails.com

KOMODO DRAGON FEEDING: PREY, HUNTING BEHAVIOR AND VENOM factsanddetails.com

KOMODO DRAGONS ATTACKS ON HUMANS factsanddetails.com

Asian Water Monitor Characteristics, Diet and Hunting

Asian water monitors can grow to three meters in length, but most adults are 1.5 meters long or less. The largest one on record, from Sri Lanka, measured 3.21 meters (10.5 feet). The color of water monitors is usually dark brown or blackish, with yellow spots on the underpart of the lizard. The yellow markings tend to diminish as they becomes older. Individuals have a black temporal band edged with yellow that extends back from each eye. The tail is laterally compressed and has a dorsal keel. The scales on the top of the head are relatively large, whil those on the back are smaller in size and are keeled. Their average lifespan in captivity is 10.6 years.[Source: Doug Byers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

range of Asian water monitors, different colors are for different subspecies

The heads of water monitors resemble those of snakes. Their neck is very long and thick. Their head has an elongated snout and can move freely. The nostrils are close to the end of the nose. Their often purple-colored tongue is forked, thin and long, and goes in and out all the time. Their tongue is similar to that of a snakes and has sensory organs on it.

Asian water monitors are extreme carnivores. This means that they eat about any animal that it believes it can consume. Common prey includes: birds and their eggs, small mammals (especially rats), fish, lizards, frogs, snakes, juvenile crocodiles, and tortoises. Like Komodo dragons, water monitors have been known to dig up corpses of humans and eat them.

The primary hunting technique used by water monitors, as well as by other monitors, is characterized by 'open pursuit' hunting, rather than stalking and ambushing. When encountering smaller prey items, water monitors subdue it in its jaws and violently thrash its neck, killing it by severely damaging the prey's organs and spine. The lizard will then swallow it whole.

The first description of a water monitor in English was in 1681 by Robert Knox during his long confinement in the Kingdom of Kandy in Sri Lanka. He wrote: "There is a Creature here called Kobberaguion, resembling an Alligator. The biggest may be five or six feet long, speckled black and white. He lives most upon the Land, but will take the water and dive under it: hath a long blue forked tongue like a sting, which he puts forth and hisseth and gapeth, but doth not bite nor sting, tho the appearance of him would scare those that knew not what he was. He is not afraid of people, but will lie gaping and hissing at them in the way, and will scarce stir out of it. He will come and eat Carrion with the Dogs and Jackals, and will not be scared away by them, but if they come near to bark or snap at him, with his tail, which is long like a whip, he will so slash them, that they will run away and howl."

Asian Water Monitor Behavior and Reproduction

Asian water monitors are excellent swimmers. They use the raised fin on their tails to steer through water. They defend themselves using their tails, claws, and jaws, and are very fast for their size due to their powerful leg muscles. While hunting for aquatic prey, Water monitors can remain submerged for up to 30 minutes. When they fight they use their flat tail as weapons. [Source: Doug Byers, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=\, Wikipedia]

Though water monitors are found on flat land, they typically make burrows in river banks. The entrance starts on a downward slope but then increases forming a shallow pool of water. The average length is about 9.5 meters, the average depth is about two meters, and the average temperature is around 26 degrees Celsius. /=\

In their aquatic habitats, the semiaquatic behavior of water monitors is considered to provide a defense against predators. When the lizards are hunted — from large snakes such as king cobras — they climb trees with their powerful legs. If still threatened they may jump from a branch of a tree into the safety of a stream or river. Green iguanas in the Americas use a similar tactic.

Males are normally larger than the females — usually about twice as large in terms of weight. Males become sexually mature when they are about one meter long; females do so when they are about 50 centimeters long. The breeding season usually lasts from April to October. The testes of males are largest during April and the females are more receptive at this time, thus there is better chance at reproductive success the earlier fertilization takes place /=\

Asian water monitors lay 15-30 eggs in dens near riverbanks or hollows of trees close to water. Under natural condition, their hatching period can be as long as a year. Larger females produce a larger clutch size than smaller individuals. The eggs are usually deposited along rotting logs or stumps. /=\

Bengal Monitors

Bengal monitors (Varanus bengalensis) are also known as common Indian monitors. Arguably the most common monitor lizard, they the have a large geographic and environmental range, occurring across much of southern Asia, from Afghanistan to Java — in southeastern Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan India, southern Nepal, Bhutan, China, Vietnam, Laos, and in Malaysia and Indonesia in the islands in the Strait of Malacca and the Greater Sunda Islands. In Iran, Iraq and Afghanistan they are generally restricted areas close to rivers, marshes or shallow lakes.[Source: Kathleen Farmer and Eric Wright, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Bengal monitors can be found in deserts, grasslands, scrub forests and rainforests and even places that get snow in the winter and up to elevations of 1500 meters (4920 feet). Usually, however, they occur in places with continuously warm climates, with mean annual air temperatures of approximately 24̊ C. Many of the places they live have a monsoon climate with wet and dry seasons. Like many other large predators, Bengal monitor lizards are relatively long-lived and appear to be relatively unaffected by drought or heavy rainfall. Mortality rates are highest for young lizards due to predation. They live up 22 years in captivity.Age estimates for reptiles are made by counting bone layers. They have annual cyclic bone growth that can be measured using by staining methods.

Bengal monitors are generally not considered threatened or endangered. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List classifies them as a species of “Least Concern”. On the US Federal List they are classified as Endangered. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix I, which lists species that are the most endangered among CITES-listed animals and plants. The main threats to Bengal monitor population are loss of habitat, commercial exploitation of their skins for leather products and the use their body parts for folk medicines. Natural predators include other Bengal monitors, pythons and other large snakes, eagles, mongooses, wild and domesticated dogs and feral cats. Most losses are a result of predation of eggs, hatchlings, and juveniles. Only rarely are fully grown adults taken.

Bengal Monitor Characteristics and Diet

Bengal monitors in the wild weigh up to 7.12 kilograms (15.8 pounds) and range in length from 61 to 175 centimeters (24 to 69 inches). Captive lizards have been reported to reach 10.2 kilograms. They are heterothermic (having a body temperature that fluctuates with the surrounding environment). Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. In the wild, males generally weigh 42 percent more than females. Males of the same snout to vent length (SVL) as females are typically are 9.2 percent heavier. [Source: Kathleen Farmer and Eric Wright, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Adult Bengal monitors are generally grey or greenish-grey in color, with a ventral pattern of grey to black crossbars from the chin to the tail. These markings are generally darkest in the western parts and lightest in the eastern parts of the geographic range. These ventral markings typically become lighter, and the ground color darker, with age. Thus, adults display a less pronounced, less contrasting pattern than younger Bengal monitors. Environmental influences play an important role in body size and overall length of Bengal monitors. In general, longer individuals are found in areas with greater soil moisture, such as marsh environments, whereas shorter individuals often occur in surrounding forests.

Bengal monitors are primarily carnivores (eat meat or animal parts). They feed on almost anything that is smaller than themselves and that they can easily overpower. They have been documented eating around 200 species, including birds, mammals, amphibians, smaller reptiles, insects, annelids, and non-insect arthropods. They and have been frequently observed eating eggs and scavenging carcasses of previously felled animals. Cannibalism of eggs, hatchlings, and even adults hhas been noted, although predation on adults is rare. As with most varanids, Bengal monitors swallow prey whole but are also capable of ripping and tearing flesh from larger animals and carcasses. Young and small-sized Bengal monitors feed primarily on insects, with beetles species making up 52.8 percent of their diet, orthopteran insects making up 9.5 percent and the remainder being other insects, crabs, rodents, reptiles, spiders and birds. /=\

Bengal Monitor Behavior

Bengal monitors are terricolous (live on the ground), diurnal (active during the daytime) and nomadic (move from place to place, generally within a well-defined range). Much of their waking, daytime timeis spent in constant movement, looking for food. In the wild, they are usually solitary, typically interacting only during the peak breading season, when males seek out females and compete for mates.[Source: Kathleen Farmer and Eric Wright, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Bengal monitors sense using vision and chemicals detected by smelling and communicate with touch and chemicals usually detected by smelling and leave scent marks produced by special glands and placed so others can smell and taste them. Like most monitor lizards, Bengal monitors use scent as their main method of communication and perception. According to Animal Diversity Web: They “taste” the environment around them by constantly flicking their highly sensitive tongues while moving their head from side to side. This is useful in tracking prey and mates and in signaling between monitors of the same species. It has been documented in the wild that Bengal monitor lizards spends large amounts of time examining the droppings of other Bengal monitors that have passed through their territory. Even though they are solitary creatures, scent messages in feces are said to be important in communication. The scent perceived by one monitor from another can inform of hostile intentions or to stay away from the particular territory. (Auffenberg, 1994) /=\

There is a diverse range of intraspecific communication exhibited by Bengal monitor lizards through touching, biting, clawing and wrestling. Being solitary predators, roughly three quarters of encounters begin as purely investigatory and the remaining quarter are for the purpose of sex and courtship. Conflict between males, whether over food or mating, usually results in an initial investigation through acquiring each others scents and their intent. Conflict typically involves vocalization which is usually a hissing noise accompanied by the monitor inflating its upper body to appear larger. Tail-slapping and whipping is also common behavior between males and sometimes females to establish dominance. Encounters between males can lead to wrestling in which case both males stand on their hind legs and embrace each other while thrashing their heads and upper bodies. Occasionally biting and clawing can occur during wrestling but it is usually collateral damage rather than intentional. /=\

Bengal Monitor Mating and Reproduction

Bengal monitors are polygynandrous (promiscuous), with both males and females having multiple partners. They engage in seasonal breeding and are oviparous, meaning that young are hatched from eggs. Females and males agriculture reach sexual or reproductive maturity at 2.5 to three years except on small islands in the South China Sea and the Gulf of Thailand where they become sexually mature at a much smaller size and younger age than those from the nearby mainland. [Source: Kathleen Farmer and Eric Wright, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

According to Animal Diversity Web: Ovulation begins in June, but reaches full force in July. The most successful copulation occurs slightly before or after ovulation has reached its peak. Egg laying will occur two weeks after copulation, usually during the months of July, August, and early September. By the last week of October, both sexes are largely inactive with size and sperm production heavily reduced in the male and new follicles for the next year appearing in the ovaries of the female. Among captive individuals day length has an effect on courtship and breeding patterns. When day length was artificially lengthened, combat among males occurred as early as April and courtship initiation and breeding began earlier. /=\

In females, the reproductive cycle is annual. Follicles mature only during one part of the year, shortly before ovulation. Follicles and ovaries reach their largest size during the months of July and August for those individuals in the western part of the species range, and from October to December for those in more southern areas such as India and Sri Lanka. Yolk deposition in an egg has no correlation with the ovulatory phase in females, but it does correlate with fat accumulation. /=\

There are three major phases in the reproductive cycle of female Bengal monitor lizards: previtellogenesis, recrudescence, and ovulation. During the previtellogenesis phase, the ovaries are small and inactive. This stage usually occurs during the fall months, usually September through March. Females forage less during this time for individuals in more southern regions, while those in more northern regions do not forage at all. A return to foraging in the spring initiates oogenesis. This phase is also characterized by regressed oviducts and nonsecretory epithelial and gland cells, which are used to attract mates.

In the second phase of the reproductive cycle, called recrudescence (or true vitellogenesis), the ovarian follicles will fully mature with the completion of yolk deposition. This phase occurs in the premonsoon period, from April to June. In a short time, the ovaries increase in size and change from a pearly white to a deep yellow color. A mature preovulatory ova has a mean diameter of 17.8 millimeters. The oviducts will also increase in width and secretions will start to flow into the oviductal lumen. The last phase of the reproductive cycle, ovulation, is characterized by the movement of the egg from the upper part of the oviduct to the lower portion after fertilization has occurred. Once the egg reaches the lower portion of the oviduct, a shell will form around each egg.

Bengal Monitor Eggs and Offspring

The gestation period of Bengal monitors ranges from four to eight months. Before young are born their sex is determined by temperature. The average number of eggs laid per year is 20, of which about 80 percent typically hatch. This results in about 16 young per female per year. Young Bengal monitors, on average, weigh 78 grams. There is little parental involvement in the raising of offspring. Pre-birth stage provisioning and protecting are done by females. Because Bengal monitor lizards have a large clutch size relative to most tropical lizards, newborns are subject to relatively high predation rates. Because of predation, roughly half of the offspring do not live past the age of two. [Source: Kathleen Farmer and Eric Wright, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Most Bengal monitor females produce one clutch of offspring each year after reaching sexual maturity for the duration of their lives. Ones that live in places with monsoon seasons may lay two clutches annually while those in one monsoon areas lay just one clutch annually. Typically, individuals mate in June, July, and early August and the shelled eggs are laid any time from July through early September.

According to Animal Diversity Web: Development in Bengal monitors begins with a variable length incubation period. Laboratory investigations have shown this incubation period to range from 70 to 327 days. The length of incubation depends largely on mean egg temperature. However, even within a single brood, there can be variations of up to 105 days from first to last hatching. High incubation temperatures typically lead to shorter development times, but also may skew sex ratios or cause developmental defects. /=\

If two clutches are laid, there are 23 to 30 days between the first egg laying and breeding for the second clutch. Data also suggests that those females from areas with plentiful rainfall have a higher proportion of pregnancies than those from areas with little rainfall. This may be due to the longer breeding periods on places with more rainfall as well as higher food abundance, which has an effect on fat production.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated February 2025