DOMESTIC CATS

Domesticated cats (“Felis cattus”) are also called domestic cats, house cats or simply cats. They come in three varieties: 1) house cats, 2) semi-feral types that use human as central base and come and go as they please, and 3) truly feral varieties. House cats have an average life span of 14 to 17 years (one in England lived to be 34).

Domesticated cats evolved from wildcats. Members of the domestic cat lineage include the Pallas's cat (Asia), Chinese desert cat (Asia), sand cat (Asia, Africa), Jungle cat (Asia, Africa), black-footed cat (Africa), and wild cat (Europe, Africa, Asia).

Domesticated cats first appeared around 10,000 years ago, later than dogs, sheep, and some other domesticated animals. Most likely the descendants of the African wild cats, they first appeared in the Middle East and northeast Africa when mankind switch from nomadism to a settled agricultural life in which cats were useful in exterminating rats and other grain-eating rodents. African wild cats are small pale yellow creatures with black feet.

Maine Coons are considered by many to be the largest true domestic cat breed because of their long bodies and relatively heavy weight. Maine Coons can be easily be over a meter in length if there tail is included and and can weigh over 11 kilograms although eight kilograms is much more common. The Singapura, is the smallest cat breed, according to Purina. Its name means "Singapore" in Malay and it originated from there. Adult females weigh around two kilograms (between four and five pounds), while males weigh about three kilograms (six to eight pounds) according to the Cat Fanciers' Association. [Source: Omlette UK, Olivia Munson, USA TODAY, September 7, 2024]

"Cats are certainly more mysterious and complex than we would ever think," Leslie A. Lyons, who studies cat genetics at the School of Veterinary Medicine at the University of California at Davis, told the Washington Post. "However, we're starting to get their story." [Source: Rob Stein, Washington Post, March 17, 2008]

Websites and Resources on Animals: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; BBC Earth bbcearth.com; A-Z-Animals.com a-z-animals.com; Live Science Animals livescience.com; Animal Info animalinfo.org ; World Wildlife Fund (WWF) worldwildlife.org the world’s largest independent conservation body; National Geographic National Geographic ; Endangered Animals (IUCN Red List of Threatened Species) iucnredlist.org

Wildcats

Wildcats is the term used for a species complex comprising two small wild cat species: 1) European wildcats (Felis silvestris), which inhabits forests in Europe, Anatolia and the Caucasus; and 2) African wildcats (Felis lybica), which are found semi-arid landscapes and steppes in Africa, the Arabian Peninsula, Central Asia, into western India and western China. The two wildcat species differ in fur pattern, tail, and size: the European wildcat has long fur and a bushy tail with a rounded tip; the smaller African wildcat is more faintly striped, has short sandy-gray fur and a tapering tail;the Asiatic wildcat (F. lybica ornata) is spotted. [Source: Wikipedia]

Wild cat can refer to any wild cat. Here we use the term wildcat to refer to a specific group of small cats that are widely distributed and live in a variety of habitats. For a long time Felis silvestris was regarded as being made up of three, distinct groups (or subspecies): 1) F. silvestris lybica (African wildcats); 2) F. silvestris silvestris (European wildcats); and 3)F. silvestris ornata, (Asiatic wildcats). Now European wildcats (Felis silvestris, formerly F. silvestris silvestris) are recognized as a separate species, distinct from African wildcats (Felis lybica, formerly F. silvestris lybica); and Asiatic wildcats (F. lybica ornata, formerly F. silvestris ornata) are considered a subspecies of African wildcat. Domestic cats are thought to be descended from African wildcats.

Wildcats are similar in size to domestic cats but have longer legs. Their back fur is usually buff grey and their underside is pale ocher. They have bushy tails and a well-defined pattern of black stripes over their entire body. The fur is short and soft. Primarily nocturnal, they have reddish ears and black leg markings. Common and very fierce for their size, they eat rodents, birds and snakes, and give birth to up to four young. Their lifespan in the wild is as high as 15 years. Their lifespan in captivity is as a high as 30 years.

See Separate Article: WILDCATS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, SPECIES AND SUBSPECIES africame.factsanddetails.com

House Cat Characteristics

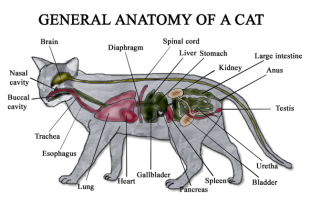

House cats range in weight from 4.1 to 5.4 kilograms (9 to 12 pounds). Their average head and body length is 76.2 centimeters (30 inches). Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. They have acute senses of hearing and vision; display excellent balance and control of their bodies; and keep themselves exceptionally clean. Female house cats mature at the age of 6 or 7 months and males between 10 and 11 months. [Source: Nicolle Birch Anna Toenjes, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

According to Animal Diversity Web (ADW): There are over 100 breeds of domestic cats but all have a very similar body shape and size. Interbreed variation is defined based on coat type and coloration or patterning of the fur. Domestic cat have approximately 244 bones in their body, of which about 30 are vertebrae (the number can vary depending upon the length of cat). With so many vertebrae in their spine, cats are very flexible and can rotate half of their spine 180°. They are capable of jumping five times their own height and are able to slip through narrow spaces because they have no collar bone and their scapulae lie medially on their body. Each forelimb (i.e., manus) has five digits and the hindlimbs (i.e., pes) have four.

Polydactyly is not uncommon among house cats. They have retractable claws on each paw, which typically do not extend when the animal walks. They have 26 teeth that usually develop within the first year. The dental formula for this species is 3/3, 1/1, 2/2, 1/1. When kittens are about two weeks old they develop deciduous or milk teeth above the gums. By the end of the fourth month the milk incisors are replaced by permanent teeth. /=\

House Cat Coat Patterns

Domestic cats have been selectively bred by humans for many years so they have a wide array of body shapes and colors — from hairless forms to long-haired Persians and tail-less Manx cats to very large Maine coon cats. Colors range from black through white, with mixtures of reds, yellows, and browns also occurring. [Source: Tanya Dewey, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

On how genes determine a cat’s coat pattern, AP reported: “Scientists say they've found the gene that sets the common tabby pattern---stripes or blotches. It's one of several genes that collaborate to create the distinctive design of a cat's coat, and it's the first of the pattern genes to be identified. Cats with narrow stripes, the so-called "mackerel" pattern, have a working copy of the gene. But if a mutation turns the gene off, the cat ends up with the blotchy "classic" pattern, researchers in the journal Science. [Source: Malcolm Ritter, Associated Press, September 20, 2012]

It's called "classic" because "cat lovers really like the blotched pattern," said one of the authors, Greg Barsh. He works at both Stanford University and the HudsonAlpha Institute of Biotechnology in Huntsville, Ala. The research team, which included scientists from the National Cancer Institute, examined DNA from wild cats in California to identify the gene. They also found that a mutation in the same gene produces the blotches and stripes of the rare "king" cheetah, rather than the spots most cheetahs have.

Leslie Lyons, a cat geneticist who studies coat color traits at the University of California, Davis, but didn't participate in the new work, agreed that the research has identified the tabby's stripes-versus-blotches gene. She noted that mysteries remain, like just what genetic machinery gives a tabby spots.

Domestic Cat Behavior

House cats have a range up to one kilometer from their homes. They are difficult to train but some have been taught to jump through hoops, dance on their hind legs and do other tricks. And, they are not necessarily stoic loners they are made out to be. One cat was so upset by its owners death it reportedly visited her grave every day.

Domestic cats are scansorial (able to or good at climbing), cursorial (with limbs adapted to running), terricolous (live on the ground), nocturnal (active at night), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), solitary, territorial (defend an area within the home range), and have dominance hierarchies (ranking systems or pecking orders among members of a long-term social group, where dominance status affects access to resources or mates). [Source: Nicolle Birch Anna Toenjes, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

The home range of domestic cats varies greatly, depending on individual habitat. For example, male farm cats tend to have 150 acres of territory and female farm cats 15 acres. In urban areas territories are significantly decreased and often overlap. Males tend to have territories that overlap those of several females, which increases their number of potential matings.

According to to Animal Diversity Web: Territorial boundaries are demarcated by adult cats via rubbing or marking with urine. Scent is produced by glands near the ears, neck, and back of the head, and is released by rubbing against an object. When a cat scratches something with its claws to sharpen them, scent is released via pedal glands. Sharpening claws on an object or rubbing against it are forms of gentle marking, whereas spraying is used to establish territorial (defend an area within the home range), boundaries. Males tend to make territories more often than females. (Alderton, 2002) /=\

House cats sometimes mimic nursing by chewing or sucking on fabrics or other household items. This is considered a comfort-seeking behavior common in kittens but is rare in adults unless they are removed from their mother too early to be weaned. Adult sucking or chewing is found most commonly in Siamese or Burmese breeds and usually continues throughout the animal's life. This type of behavior has been likened to obsessive compulsive disorder in humans caused, in part, by a genetic predisposition. House cats with little access or exposure to plants often chew on plants inside the house, which may be a sign that the cat is craving plant matter or that their diet is fiber deficient. /=\

Certain behaviors can be a nuisance to humans if not stopped early on. Kitten behavior can often be aggressive as kittens are still learning behavioral patterns from their peers or family. If a kitten is raised in the absence of family or play mates the play aggression has a much higher chance of becoming more severe and permanent. Unprovoked aggression towards humans may be the result of other stimuli, such as seeing a bird or animal outside and the behavior is then redirected toward a person. Males often show more aggression toward each other than toward females. /=\

Domestic Cat Food and Eating Behavior

Domestic cats are primarily carnivores (mainly eat meat or animal parts) and mostly eat terrestrial vertebrates. Animal foods include birds, mammals, fish insects. Among the plant foods they eat are leaves. According to Animal Diversity Web: a healthy diet consists of about 30 to 35 percent muscle meat, 30 percent carbohydrates, and eight to 10 percent fats, which promote growth and healthy skin and coat. Feral cats may hunt for rodents or birds. Some domestic cats depend on human supplied feed. Adult females require around 200 to 300 calories per day, whereas adult males need between 250 and 300 calories per day. In order to kill their prey, all felids bite the back of the neck at the base of the skull, thus, severing the spinal chord from the brain stem. Primary prey for feral animals includes small rodents, birds, fish, and some arthropods. Occasionally, domestic cats ingest plant material to fulfill fiber deficiencies. [Source: Nicolle Birch Anna Toenjes, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Commenting on how domestic cats have moved beyond the group hunting tactics used by lions, David Attenborough wrote: “The ancestor of the domestic cat is the European wild cat that lives in the Middle East and Africa. Like most other cats, they are solitary creatures. But domesticated cats that have run wild, either in cities such as Rome or in farmyards, have found food on a scale their wild ancestors never had. In farmyards, a cat needs no help in pouncing on a mouse. In a city center it needs no assistance in making a meal from the discarded remains of a chicken dinner.

“In such places there is enough food to support great numbers of these ferocious feral hunters. But they do not all compete with one another indiscriminately. They form teams. Females assist their sisters, daughters and even granddaughters. They live in close proximity with one another and band together to keep away any unrelated cats that seek to take up residence in their territory. They produce their kittens in a communal den and nursing mothers even allow their nephews and nieces to suckle. And tom cats living in smaller numbers alongside these female groups will kill the kittens fathered by their rivals. The parallel with lion prides is certainly a close one.”

Domestic Cat Senses and Communication

Domestic cats sense using vision, touch, sound, vibrations and chemicals usually detcted with smell and communicate with vision, touch, sound, chemicals usually detected by smelling, mimicry, pheromones (chemicals released into air or water that are detected by and responded to by other animals of the same species) and scent marks produced by special glands and placed so others can smell and taste them. [Source: Nicolle Birch Anna Toenjes, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

According to Animal Diversity Web: Body language and vocalizations are ways in which domestic cats communicate with members of their own species. Relaxed individuals often have their ears forward and whiskers relaxed. Adults display contentedness via purring. Kittens also purr and knead or prod when content and suckling their mother. Domestic cats also "meow", which changes meaning in relation to posture. If a cat is upset it will likely growl, hiss, or even spit at another cat or animal. In general, cats have advanced auditory perception. Their ears can rotate 180° to either face frontward or be flattened back or any direction in between. With three inner ear canals in each of the three dimensional planes, domestic cats have a great sense of balance. Their ears are sensitive enough to hear ten octaves, which is two more than a human can hear. Domestic cats can hear a broad range of frequencies, from 50 to 65 kilohertz, versus humans which can only hear sounds between 18 and 20 kilohertz. They have vibrissae on the muzzle, eyebrows, and elbows which function as haptic receptors. These touch receptors allow house cats to navigate their way around obstacles in low light conditions by sensing changes in air flow around an object as it approaches it. /=\

Peripheral vision in domestic cats is very good but their eyes are also farsighted (an adaptation for hunting), which doesn't allow them to focus on objects within two feet. A reflective membrane in the back of the eye, called the tapetum lucidum, reflects light from behind the eye's retina and intensifies it. Species possessing tapetum lucidum are able to see exceptionally well in low light. Cats cannot see most colors, although some researchers believe that they may be able to see red and blue. The third eyelid, or haw, is a semi-transparent protective lid which typically retracts into the inner corner of the eye. /=\

With about 200 million olfactory cells, the nose of domestic cats is about thirty times more sensitive than that of humans. Jacobson's organ (i.e., the vomeronasal organ) is located immediately dorsal to the hard palate and is particularly exposed to scent molecules when an individual inhales via the mouth. A domestic cat's tongue is covered in hundreds of papillae; hook-like structures, which face backwards and are used to comb and clean the fur. Domestic cats sometimes socially groom, but typically grooming is a singular task unless the cat is the individual's mother. Taste buds are located on the sides, tip, and back of the tongue and allow domestic cats to perceive bitter, acidic and salty flavors but not sweet. /=\

Cats Better at Word Association than Human Babies

Cats form associations between pictures and words around four times faster than human toddlers do according to research published in October 2024 in the journal Scientific Reports. "Cats can definitely recognize the sound of words coming from people, and more and more studies prove that cats rely on interaction with humans in problem-solving," Dr. Carlo Siracusa, a veterinary behaviorist at the University of Pennsylvania, told Live Science. [Source Victoria Atkinson, Live Science, November 7, 2024]

Victoria Atkinson wrote in Live Science: There is even limited evidence that cats can respond to pointing, and research in recent years has shown that cats can recognize not only their own names but also those of familiar humans and animals. But can they associate words and objects more generally? To test this theory, Saho Takagi and her team at Azabu University in Japan gave 31 adult cats a simple word game used to investigate the same ability in babies. The cats were shown two nine-second cartoon clips with recordings of their owners repeating a made-up word over each image. The sequence of clips — a red sun labeled "paramo" and a blue unicorn with the word "keraru" — was repeated until the cats appeared to get bored and paid 50 percent less attention to the screen.

After a short break, the image clips were repeated, but this time, half of the pairings were inverted. The switched clips visibly confused the cats, with recordings of "paramo" alongside the unicorn and "keraru" with the sun holding feline interest an average of 15 percent longer. That the cats noticed this change and were clearly perplexed by it is good evidence that they had formed a link between the words and images, Takagi and colleagues wrote in the study. "Some cats even gazed at the screen with their pupils dilated during the 'switched' condition," Takagi told Science magazine. "It was cute to see how seriously they participated in the experiment." The experiment revealed that the cats were able to learn the combinations from just two nine-second exposures — significantly faster than toddlers, who required at least four 20-second trials.

However, these comparisons should not be overinterpreted. "You're comparing an adult animal with an immature animal from a different species," Siracusa told Live Science. "In addition, we humans are interpreting the behavior of a completely different species. When we interpret children's behavior, we are interpreting the behavior of our same species, which we are programmed by natural selection to perceive in an innate way."

Domestic Cat Mating and Reproduction

House cats are polygynandrous (promiscuous), with both males and females having multiple partners. Females go into a five-day heat, during which time they twist around and let out unearthly calls, the source some say of links between cats and the Devil. Males respond to the calls and fight with one another and chase the females around. When a female accepts male, copulation is short and violent with the male often biting into the female’s neck. They often mate several times and fight afterwards.

House cats are iteroparous. This means that offspring are produced in groups such as litters multiple times in successive annual or seasonal cycles. They engage in year-round breeding. Females go into oestrus (heat) approximately every 21 days during the breeding season unless mated. March to September in the northern hemisphere or October to March in the southern hemisphere.[Source: Nicolle Birch Anna Toenjes, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Male house cats patrol territories in search of estrus females during mating season. Estrus females call loudly to potential mates, while continually rolling on the ground. When a potential mate arrives, females present their rumps, which lets the male know they are in estrus. When a pair meets, they may mate many times over a few hours before parting ways. Females have induced ovulation which is stimulated by copulation.

Domestic Cat Offspring and Parenting

The gestation period for house cats ranges from 60 to 67 days, with an average of 63 days. Most females give birth to around four kittens. As many as 18 kittens in a single litter has been reported. Newborn weight ranges from 110 to 125 grams. Most kittens are weaned by seven to eight weeks after birth and are completely independent by 12 weeks. On average females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at six months and males do so at eight months. [Source: Nicolle Birch Anna Toenjes, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Young are precocial. This means they are relatively well-developed when born. During the pre-birth, pre-weaning and pre-independence stages provisioning and protecting are done by females. There is an extended period of juvenile learning. /=\

According to Animal Diversity Web: Domestic cat kittens are cared for by their mothers and paternal care is virtually non-existent. In some cases, unrelated females may aid new mothers by caring for and nursing her kittens while she hunts. This behavior is rare, however, and often mothers are forced to leave their kittens unguarded while hunting. Mothers also purr to their kittens, which is thought to reduce stress levels. Females nurse their kittens until around eight weeks after birth, when weaning is completed. Prior to independence, kittens learn how to hunt by mimicking their mother. Mothers also take an active role in teaching their young how to hunt by allowing them to hunt only very small animals, such as mice. Kittens are not permitted to hunt larger prey, such as rats, right away. Weaning is usually complete by seven to eight weeks; however, kittens do not leave their mother until they are six to eight months old, depending on sex.

Breeds of Domesticated Cats

There are 73 breeds of cat recognized by the IPCBA (International Progressive Cat Breeders Alliance), , including dainty Abyssinians and snow white Persians, Havana brown, Burmese, Singapura, Siberians, Norwegian forest cats, Maine coons and Japanese bobtails.. The short hairs include Siamese, Abyssinian, Burmese, Russian blue, Havana brown, Rex, Manx, Korat and Charteux. The long hairs include Persians and Himalayans. Breeds look very different because of variations in a single gene, which is not enough to distinguish them genetically.

Rob Stein wrote in Washington Post, “Lyons and her colleagues also made surprising discoveries about individual breeds. "We wanted to see whether breeds actually came from what was thought to be their geographical origins," Lyons said. The Japanese bobtail, for example, does not seem genetically similar to cats from Japan, indicating the breed may have originated elsewhere. "Either it didn't originate in Japan or there's been so much Western influence that they have lost their initial genetic signal," Lyons said. [Source: Rob Stein, Washington Post, March 17, 2008]

“Despite its name, the Persian, the oldest recognized breed, looks as though it actually arose in Western Europe and not Persia, which today is Iran. "If it came from Iran, you would think it would look like cats from Turkey and Israel," she said. Instead, the Persian "looked more like a Western European cat." When the researchers examined the genes of what are thought to be distinct breeds, they were unable to find significant differences among many of them. "An example would be Persian and exotic shorthairs. When you look at those two breeds, you can't distinguish them from one another" by their genes, she said. The same was true for the Burmese and the Singapura, as well as the Siamese and the Havana brown. While Havana browns are considered a separate breed in the United States, European cat breed associations consider them a color variation of Siamese.

“The researchers also found interesting relationships that track human history. Italian and Tunisian cats, for example, are a mix of Western European and Mediterranean cats, probably reflecting the close historical ties between Tunisia and western Europe. Cats from Sri Lanka and Singapore are a genetic melange of cats from Southeast Asia, Europe and elsewhere, which could be a "relic of British colonialism," the researchers wrote. The same goes for the Abyssinian.

“The finding that cat lovers should be concerned about is that some breeds have become so inbred that the amount of genetic variation among them is getting dangerously low. That tends to lead to higher levels of illness, Lyons said. "That could have consequences for the cats' health. The more genetic variation, generally the healthier the population will be. So some cat breeders need to be careful that there's not too much inbreeding going on," she said.The Burmese and Singapura breeds had the least diversity, she said, while Siberians had the greatest, along with Norwegian forest cats, Maine coons and Japanese bobtails. About half the breeds examined had genetic variation comparable to randomly bred cats, which is good, but the other half had less. "You don't want to say they are in trouble, but it's something we should note," Lyons said.

“Despite the shrinking genetic diversity, purebred cats remain far more genetically diverse than purebred dogs, noted Marilyn Menotti-Raymond, who studies cat genetics at the National Cancer Institute. That's because people have been breeding cats for about 200 years at most, and there is more interbreeding than among purebred dogs, she said. "Everyone is aware of the problems that can occur from the small gene pool in some dog breeds," said Menotti-Raymond, who, in the same issue of the journal Genomics, reported similar findings in a different sample of 611 cats representing 38 breeds. "I was actually surprised at the level of genetic diversity in cats, and that's good."

Domesticated Cats as Pests

Domestic cats carry a number of diseases that may be transmitted to humans, including rabies, cat-scratch fever, and several parasitic infections. Domestic cats are also responsible for population declines and extinctions of many species of birds and mammals, particularly those restricted to islands. Efforts to control populations of domestic cats can be very expensive, laborious and cruel. [Source: Nicolle Birch Anna Toenjes, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

Cats are one of the most damaging alien killers, wrecking havoc among local species. A study in Britain in 1997, found that 1,000 cats killed more than 14,000 mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians, including some endangered species, during a single spring and summer. Based on this study, it is estimated that Britain's 9 million pet cats kill 250 million creatures year. House cats were introduced before 1800 to Australia. They have decimated wildlife in western Australia and contributed the extinction of ten native mammals. Australia's three to four million feral cats are responsible for killing as many as four million native creatures.

According to Reuters: “Domestic cats, introduced globally by humans, are considered among the 100 worst non-native invasive species in the world yet control of the creatures has not been widely addressed by local, state and federal governments. Despite mounting evidence that free-roaming cats are exacting a severe toll on wildlife and contributing or even causing the extinction of some birds, mammals and reptiles, management of cats is strongly shaped by public opinion, or emotion, rather than science,. “A major reason for the current nonscientific approach to management of free-ranging cats is that the total mortality from cat predation is often argued to be negligible compared with other (human-caused) threats such as collisions with manmade structures and habitat destruction,” researchers say. [Source: Reuters, January 31, 2013]

In densely-populated urban areas where native wildlife is scarce cats largely prey on non-native mice and rats but in suburban and rural areas cats kill mostly native mice, shrews, voles, squirrels and rabbits, Cats are also blamed with transmitting diseases to wildlife populations.

Study of Damage Caused by Cats to Wildlife

In January 2013, Reuters reported: “Think of cats as cute purring bundles of fur? Think again. A new study says free-roaming kitties are serious killers. Such cats are a leading cause of deaths of birds and small mammals in the United States, with pet and ownerless cats blamed for killing up to 3.7 billion birds and as many as 20.7 billion other animals each year, government scientists said in a study released. Ownerless cats, including barn cats, strays and feral colonies, are behind the vast majority of bird and mammal deaths, according to the study, “The impact of free-ranging cats on wildlife in the United States,” published in the online journal Nature Communications and authored by according to the study authored by Peter Marra and Scott Loss of the Smithsonian and Tom Will of the Fish and Wildlife Service’s Division of Migratory Birds. [Source: Reuters, January 31, 2013]

“The study is the first to compile and systematically analyze rates of cat predation. It suggests cats cause “substantially greater wildlife mortality than previously thought,” and are likely the single greatest source of mortality linked to human settlement for US birds and mammals. The findings by researchers with the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute and the US Fish and Wildlife Service show the bulk of birds killed by cats in the United States — excluding Alaska and Hawaii — were native species such as robins, finches and chickadees.

Birders hailed the study even as lovers of the nation’s estimated 120 million cats assailed it. The American Bird Conservancy said the new findings should be a wake-up call for cat owners and communities. “We all love cats, they’re cute, they’re furry, but we can no longer continue to allow these predators to be turned loose on an unsuspecting and defenseless environment,” said conservancy spokesman Robert Johns.Carol Barbee, past president of the American Cat Fanciers Association, expressed concerns about any study that raises the spectre of “killer kitty.” “Outside cats perform their duty: they catch mice and rats and things that are their job to catch,” she said. “And, yes, they’re going to catch the occasional bird. But I don’t personally believe they’re responsible for mass death and destruction.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2025