ELEPHANTS

African Elephant

Elephants are the largest land animals. Many species of whales and some sharks are larger. There are three species: the African elephant, which ranges across much of sub-Sahara Africa; the forest elephant which lives in rain forests in Africa and the Asian elephant, which is found in South Asia, Southeast Asia and Indonesia. Scientists decided to make the forest elephant a separate species in the 2002 based on genetic differences.

Elephants are sometimes referred to as "pachyderms" (meaning "thick skinned"). A male elephant is called a bull. A female is called a cow. Young are called calves. A group is called a herd.

When asked why she loves studying elephants, elephant expert Cynthia Moss told the Los Angeles Times, “They are so interesting and intelligent and complex, and they have a very interesting social life. They're long-lived, therefore you can really get your teeth into a study of them.” [Source: Thomas H. Maugh II, Los Angeles Times, July 19, 2010]

The total number of elephants in Africa is now estimated to be around 415,000. [Source: Christina Larson, Associated Press, February 15, 2022]

Websites and Resources: Save the Elephants savetheelephants.org; International Elephant Foundation elephantconservation.org; Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; BBC Earth bbcearth.com; A-Z-Animals.com a-z-animals.com; Live Science Animals livescience.com; Animal Info animalinfo.org ; World Wildlife Fund (WWF) worldwildlife.org the world’s largest independent conservation body; National Geographic National Geographic ; Endangered Animals (IUCN Red List of Threatened Species) iucnredlist.org

Books:” The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Elephants” by S.K. Elfringham (Smithmark Publishers, 1997), “Elephants" Majestic Creatures of the Wild “edited by Jeheskei Shosani (Rodale Press, 1992); “Silent Thunder: In the Presence of Elephants” by Katy Payner (Simon & Schuster, 1998).

Sources: Douglas Chadwick, National Geographic, May 1991 [←]; Katharine Payne, National Geographic, August 1989; Oria Douglas-Hamilton, National Geographic, November 1980; Eric Dinerstein, Smithsonian, September 1988;

RELATED ARTICLES:

MAIN ELEPHANT FEATURES: TUSKS, TRUNK AND EARS factsanddetails.com

ASIAN ELEPHANTS: CHARACTERISTICS, NUMBERS, NATURAL DEATHS factsanddetails.com

ASIAN ELEPHANT BEHAVIOR: MUSTH, MOURNING AND DRUNKENNESS factsanddetails.com

ELEPHANT BEHAVIOR: INTELLIGENCE, FEEDING AND GETTING HIGH factsanddetails.com

ELEPHANT SOCIAL BEHAVIOR: COMMUNICATION, SEX, RANK, EMPATHY AND MOURNING factsanddetails.com

MAMMALS: HAIR, CHARACTERISTICS, WARM-BLOODEDNESS factsanddetails.com

Elephant History

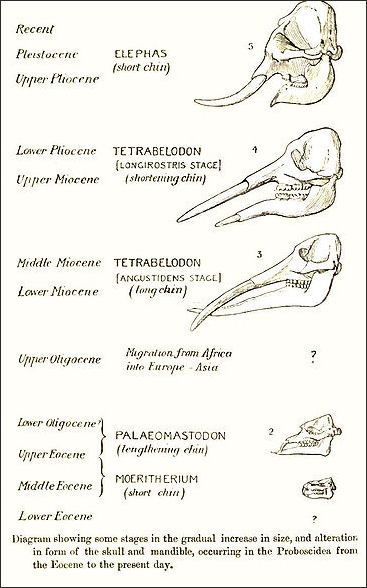

The ancestor of elephants, mammoths and mastodons was a pig-size animal with an upper lip like a tapir that lived about 55 million years ago. As these creatures evolved their heads got small and their upper lip became longer and more flexible until it became a trunk.

More than 250 species of elephants and elephant-like creatures have roamed the earth in the past. Ancestors of the elephant include the “Moeritherum” (a pig-like animal that lived 40 million to 30 million years ago), the “Piomia” (a pig-like animal with a long snout that lived 37 million to 28 million years ago), “Deinotherium” (an elephant-like animal with downward-hooking tusks that lived 24 million to 1.8 million years ago), the “Primelephas” (an animal that looked like a modern elephant and lived from 6.2 million to 5 million years ago).

African elephants and Asian elephants diverged from a common ancestor about 6 million years ago. They lived at the same time as American mastodons (who lived from 3.75 million to 11,500 years ago) and wooly mammoths (who lived from 400,000 to 3,900 years ago). Ancestors of elephants, such as mastodons and wooly mammoths, have been found all the continents except Antarctica and Australia. In 2009, a well-preserved, 200,000-year-old skeleton of a giant prehistoric elephant was found in Java, which itself was unusual in that bones usually decompose quickly in humid, tropical climates. The animal stood four meters tall and weighed more than 10 tons, which was closer in size to a wooly mammoth than a modern Asian elephants. Another Indonesian, Flores, was the home of stegodons — extinct elephant ancestors which were about the size of a cow, or about a tenth of the size of an Asian elephant.

The Asia elephant once ranged as far west as the Tigris and Euphrates region of Syria and Iraq and as far north as Manchuria in China. Based on mitochondrial DNA evidence, there are two main lineages of Asian elephants that split from each other about three million years ago. Most belong to the “alpha” lineage. Those in peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra and Borneo belong to the “beta” lineage. For reasons that are not clear, Both lineages are found on Sri Lanka.

Difference Between Asian Elephants and African Elephants

Asian elephants have an arched back, two watermelon-size humps on their forehead, relatively small tusks, four toes on their front feet, smoother skin, relatively small ears that fold forward and are shaped like India, and a single finger-like protuberance at the tip of their trunk. Only males have tusks.

Adult male Asian elephants weigh up to four tons and stand 9 to 10½ feet tall at the shoulder, and females weigh as much 3.3 tons. The largest Asian elephant was an animal found in Nepal named Tula hatti ("the great elephant") that stood 11 feet at the shoulder and had a foot print that measured 22 inches across. Their mellow temperament allows them to be trained for entertainment in circuses and heavy labor such as lifting logs onto trucks and pulling them through the forest.

Asian elephants often have patches of white skin on their trunks and ears but it is often difficult to see them and tell the true color of an Asian elephant because after they bath they use their trunks to cover themselves with dirt. The elephants od this to suffocate pests and fool of their skin, much the same way a woman powders her skin after a bath.

African elephants have darker skin, large tusks, a smooth forehead, a dip in their back, five toes on their front feet, large ears that fold backward over the shoulder, and two finger-like protuberances at the tip of their trunk. Both male and females have tusks.

Adult male African elephants weigh up to six tons and stand 11 feet tall at the shoulder, and females weigh as much four tons. Bush elephants live in most countries south of the Saharan and forest elephants live Cameroon, Congo, Ivory Coast and other central and west African nations. African elephants are more difficult to tame than Asian elephants although some have been trained for circus and as mounts for tourists in southern Africa.

African and Asian elephants are different enough that they can not can not produce offspring. By contrast, lions and tigers can produce offspring if they mate.

Elephant Age

Asian elephant

On average an Asian elephants lives to be around 40 or 50. Their life cycle closely parallels that of humans. They reach sexual maturity at the age of 11 to 14, reach full growth at around 30, and die around 50 or 60 in captivity (they die sooner in the wild which is a less forgiving environment for old elephants). Scientists measure their age by measuring the size of their footprints.

The oldest verified age of a mammal other than human is 78 years, by a female Asian elephant that died in a zoo in Santa Clara, California in July 1975. Whales are believed to live longer but it is difficult to verify their age.

Interestingly the number heartbeats on the life of an elephant is approximately equal to the number heartbeats on the life of a shrew. An elephant’s heart beats about 20 times a minute while the heart of a shrew, which lives only one or two years, is around 600 beats a second.

Elephants live longer in wild than zoos according to a study published in Science in December 2008. Randolph E. Schmid of AP wrote: “Researchers compared the life spans of elephants in European zoos with those living in Amboseli National Park in Kenya and others working on a timber enterprise in Myanmar. Animals in the wild or in natural working conditions had life spans twice that or more of their relatives in zoos. [Source: Randolph E. Schmid, AP, December 11, 2008]

The researchers found that the median life span for African elephants in European zoos was 16.9 years, compared with 56 years for elephants who died of natural causes in Kenya's Amboseli park. Adding in those elephants killed by people in Africa lowered the median life span there to 35.9 years. Median means half died younger than that age and half lived longer. For the more endangered Asian elephants, the median life span in European zoos was 18.9 years, compared with 41.7 years for those working in the Myanmar Timber Enterprise. Myanmar is the country formerly known as Burma.

Elephants Live Longer in Wild than Zoos

Elephants live longer in wild than zoos according to a study published in Science in December 2008. Randolph E. Schmid of AP wrote: “Researchers compared the life spans of elephants in European zoos with those living in Amboseli National Park in Kenya and others working on a timber enterprise in Myanmar. Animals in the wild or in natural working conditions had life spans twice that or more of their relatives in zoos. [Source: Randolph E. Schmid, AP, December 11, 2008]

The researchers found that the median life span for African elephants in European zoos was 16.9 years, compared with 56 years for elephants who died of natural causes in Kenya's Amboseli park. Adding in those elephants killed by people in Africa lowered the median life span there to 35.9 years. Median means half died younger than that age and half lived longer. For the more endangered Asian elephants, the median life span in European zoos was 18.9 years, compared with 41.7 years for those working in the Myanmar Timber Enterprise. Myanmar is the country formerly known as Burma.

elephant heart, 20 to 30 kilograms

The life spans of zoo elephants have improved in recent years, suggesting an improvement in their care and raising, said one of the report's authors, Georgia J. Mason of the animal sciences department at the University of Guelph, Canada. But, she added, "protecting elephants in Africa and Asia is far more successful than protecting them in Western zoos." "One of our more amazing results" was that Asian elephants born in zoos have shorter life spans than do Asian elephants brought to the zoos from the wild, she added in a broadcast interview provided by the journal Science, which published the results in its Friday edition.

She noted that zoos usually lack have large grazing areas that elephants are used to in the wild, and that zoo animals often are alone or with one or two other unrelated animals, while in the wild they tend to live in related groups of eight to 12 animals. In Asian elephants, infant mortality rates are two times to three times higher in zoos than in the Burmese logging camps, Mason said. And then, in adulthood, zoo-born animals die prematurely. "We're not sure why," she said.

The study confirms many of the findings of a similar 2002 analysis prepared by the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. One of the authors of the new study, Ros Clubb, works for the society. Steven Feldman, a spokesman for the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, contended the report did not reflect conditions in North America. In addition, he said, it is hard to compare conditions in zoos and in the wild. "Every event in a zoo is observed," he said, while scientists can study only a small number of events in nature.

Elephant Characteristics

A running elephant reach speeds of 25 miles per hour (compared to 70 mph for a cheetah and 27.9 mph for the world's fastest human). A charging elephant can reportedly maintain a 35 miles per hour pace for 120 yards. A trotting elephant can maintain speeds exceeding 18 miles-per-hour for more than a kilometer. Elephants move 15 to 20 miles a day. The movement keeps their nails trimmed. Captive animals have to have their nails filed.

Elephants have wrinkled inch-thick skin but lack sweat glands. To keep cool elephants they flap their well veined ears and seek water for relief. When severely overheated elephants may draw water from their throats or stomachs and spray their ears. Mosquitos have no trouble penetrating the skin of elephants.

Elephants have a low heart rate, about 20 to 30 beats a minute. This allows them to do relatively strenuous exercise for long periods of time. For their size, elephants have fairly small muscles. Some scientists are studying this relationship because it makes them analogous to obese humans or people with weak or paralysed muscles.

Jennie Rothenberg Gritz wrote in Smithsonian magazine: “But elephants have a sense of smell that’s almost like a superpower. When you come close to an elephant it will point its trunk toward you like a periscope. “He’s exploring his environment, taking in scent,” an elephant keeper at the zoo told me when I asked why a trunk was unfurling in my direction. “Smellevision.” [Source: Jennie Rothenberg Gritz, Smithsonian magazine, April 2020]

Elephant Feet and Toes

Elephants have huge calloused footpads. They can walk very carefully and are remarkably light on their feet and walk noiselessly at 4mph. They can also balance on balls, play catch, and dance. Elephants can't hop, jump or gallop and they are afraid of steep places because they hurt themselves severely if they fall.

In 2011 it was revealed that elephants have sixth 'toes.' AFP reported: “A bony growth in elephants' feet is a sixth "toe" that helps the world's heaviest land mammal keep its balance, scientists said. The growth protruding from the back of elephant's feet was discovered in the 18th century when a Scottish surgeon dissected one of the creatures for the first time.Researchers had been baffled by the piece of bone but a new study in the US journal Science claims to have solved the mystery. While not a true toe, the growth has developed the same function as a toe, giving the behemoths much-needed help in supporting their colossal weight as they lumber across African plains and through Asian jungles. [Source: AFP, December 23, 2011]

"It is performing the function of a toe in supporting the elephant's weight," lead author Professor John Hutchinson, of Britain's Royal Veterinary College, told BBC radio. "It is a little weird piece of bone that has been elongated during evolution into quite a long piece of bone." The researchers used techniques including X-rays, dissection and an electron microscopy in their study.

“The elephant's five conventional toes point forwards but the extra "toe" points backwards to give extra support. A similar phenomenon can also be observed in pandas and moles, according to scientists. A panda's "sixth finger" helps it to grip bamboo, while the extra digit helps moles to dig. The researchers studied elephant fossils to discover when the bone first appeared and believe it was around 40 million years ago, as elephants got bigger and became more land-based.

Elephant Movement and Their Walk-like Run

In the wild, elephants roam as much as 30 miles a day. Mostly they get around by walking with some scientists even going as far as saying they are incapable of running even when moving at top speed. Scientists studying elephant movement now say when Asian elephants move fast they do not just walk fast, but they don’t quite run either. They do something in between them that leans sort of the running side. "It is certainly more than just walking," John Hutchinson of Stanford University in California told New Scientist. "It may be running, but I want to be cautious." [Source:Philip Cohen, New Scientist, April 2, 2003]

“"Elephants do not gallop," Kipling wrote. "They move...of varying rates of speed. If an elephant wished to catch a train he could not gallop, but he could catch the train." Philip Cohen wrote in the New Scientist, “To study the fast motion of elephants, Hutchinson and his colleagues in the US and Thailand performed intricate biomechanical video analysis of Asian elephants. The work may overturn the long held belief that elephants do not run, and could also give insights into the movements of other large animals, including dinosaurs. Robert Full, of University of California, Berkeley, says the work is important. "We know very little about the biomechanics of large animals," he says. "Here's a hint there's definitely something unusual going on. I can't wait to see the next study."

chargin Asian elephant

When many quadrupeds reach their top speed, all their limbs leave the ground during part of their gait. So one definition of the transition between walking and running is when the footfall pattern becomes partially "aerial". A biomechanical definition of running requires a gait where the centre of gravity of an animal moves up and down in a pogo stick-like motion.

Hutchinson's team videotaped 42 healthy, active animals whose joints had been painted with white dots, to make their movements easier to follow. To encourage the elephants acceleration, the researchers cheered the animals on, gave them food rewards, had them race their trainer or put a friendly elephant at the finish line. The results were surprising in a number of ways. The elephants' top sustained speed of 25 kilometres per hour (16 mph) is fast enough, in theory, to launch the animals into an aerial gate. But the animals always kept three feet on the ground and used the same four-step gait as when they were walking slowly.

However video analysis of the hip joint hinted that elephants do run, in a biomechanical sense. The hind limb appeared to move downwards in the middle of the stride and then upwards, a characteristic of running. That would have settled the question, except that analysis of the shoulder spot showed it moved upwards and then downwards - the biomechanical signature of walking.

While that makes an elephant gait very unusual, Hutchinson speculates that it is a variation of the "Groucho gait", named after the crouched stride of the comic actor Groucho Marx. Avoiding an aerial phase could be important for a large animal, says Hutchinson: "They wouldn't have to endure the shock of leaving the ground and falling back down." The only definitive test is to measure the force an elephant exerts on the ground at different speeds, to directly measure the extra force a running, pogo stick-like motion should create. Hutchinson and his colleagues are now designing an appropriate force platform. "The ones we have would break if an elephant moving at even moderate speed stepped on them," he notes.

Cancer-Resistant Elephants

Carl Zimmer wrote in New York Times: Scientists have speculated that large, long-lived animals must evolve extra cancer-fighting weapons. And if that’s true, they reason, then that elephants — the biggest, longest-lived animals — should have an especially big arsenal. Otherwise, these species would go extinct. “Every baby elephant should be dropping dead of colon cancer at age 3,” said Dr. Joshua D. Schiffman, a pediatric oncologist at the Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah. [Source: Carl Zimmer, New York Times, October 8, 2015]

“Writing in October 2015 in JAMA, Dr. Schiffman and his colleagues report that elephants appear to be exceptional cancer fighters, using a special set of proteins to kill damaged cells. Working independently, Vincent J. Lynch, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Chicago, and his colleagues have come to the same conclusion. Those researchers posted a draft of their paper in October 2015 on the bioRxiv server. It is currently in review at the journal eLife.

“Dr. Schiffman and his colleagues found in their research that elephants had a remarkably low rate of cancer. They reviewed zoo records on the deaths of 644 elephants and found that less than five percent died of cancer. By contrast, 11 percent to 25 percent of humans die of cancer — despite the fact that elephants can weigh a hundred times as much as we do.

Gene Involved in Elephant Cancer Fighting

Prehistoric elephant ancestors

Carl Zimmer wrote in New York Times: To understand the elephants’ defenses, the scientists investigated a gene that is crucial for preventing cancer, called p53. The protein encoded by the gene monitors cells for damage to the DNA they contain. In some cases, it prompts the cells to repair the genes. In other cases, p53 stops cells from dividing further. And in still other cases, it even causes the cells to commit suicide. [Source: Carl Zimmer, New York Times, October 8, 2015]

“One sign of how important p53 is for fighting cancer is what happens to people born with a defective copy of the gene. This condition, known as Li-Fraumeni syndrome, creates a lifetime risk of cancer of more than 90 percent. Many people with Li-Fraumeni syndrome get cancers as children and can have several types of cancer over their lifetimes. Dr. Schiffman and his colleagues found that elephants had evolved new copies of the p53 gene. While humans have only one pair of p53 genes, the scientists identified 20 pairs in elephants. Dr. Lynch and his colleagues also found these extra genes. To trace their evolution, the researchers made a large-scale comparison of elephants to other mammal species — including extinct relatives like woolly mammoths and mastodons whose DNA remains in their fossils.

“The small ancestors of elephants, Dr. Lynch and his colleagues found, had only one pair of functional p53, like other mammals. But as they evolved to bigger sizes, they steadily evolved extra copies of p53.“Whatever’s going on is special to the elephant lineage,” Dr. Lynch said.

“To see whether these extra copies of p53 made a difference in fighting cancer, both teams ran experiments on elephant cells. Dr. Schiffman and his colleagues bombarded elephant cells with radiation and DNA-damaging chemicals, while Dr. Lynch’s team used chemicals and ultraviolet rays. “In all these cases, the elephant cells responded in the same way: Instead of trying to repair the damage, they simply committed suicide. Dr. Schiffman saw this response as a unique — and very effective — way to block cancer. “It’s almost as if they said, ‘We’re elephants — we’ve got plenty more cells where those came from,’ ” Dr. Schiffman said.

“Patricia Muller, an oncologist at the MRC Toxicology Unit at the University of Leicester who was not involved in the studies, said the results, though compelling, didn’t firmly establish exactly how elephants use p53 to fight cancer. One possibility is that the extra copies don’t actually cause cells to commit suicide. Instead, they may act as decoys for enzymes that destroy p53 proteins. As a result, elephants can have higher levels of p53 than other animals. “All in all, it’s interesting, but the mechanism needs to be properly investigated,” she said.

“Dr. Muller said it was especially important to understand precisely how elephants fight cancer before trying to mimic their strategies with drugs for humans. Experiments in which mice get extra amounts of p53 have shown that the molecule has a downside: It can accelerate aging. “It has to be kept under tight control,” Dr. Muller said.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2024