ASIAN ELEPHANTS IN INDIA

India During World War II

For thousands of years, people in India have captured elephants to serve as instruments of war, beasts of burden, and to participate in religious festivals. They’re revered like gods, and adorned with embroidered garments and jewelry in parades. In the old days in India, elephants fought for the entertainment of maharajahs, who viewed them as symbols of their wealth and power. They were also used for transportation. On his visit to India, Mark Twain said, he “could easily learn to prefer an elephant to any other vehicle.” "The art of “abhyanga”, a musky rubdown of female elephants to increase their sexual attractiveness is still practiced.

Seals from the 4,000-year-old Harappa civilization depict tamed elephants. According to National Geographic: With the advent of kingdoms and republics in India in the first millennium B.C., the elephant became prominent as an animal of war — used as a fighting platform and to charge enemy ranks — and remained so until a few hundred years ago. [Source: Srinath Perur, National Geographic, April 13, 2023]

During the final day of the Mysuru Dasara festival in Mysore, India, an elaborately decorated elephant marches in a parade. At Mysuru Palace in India,elephants touch trunks, perhaps a gesture of comfort. Festivals can be stressful for elephants the day before, these animals were among large crowds of people at the Dasara celebration.

Elephants in India have also been harshly mistreated. According to National Geographic: Beneath the flowers and ornaments, these elephants often have scars from the hooks, prods, and shackles used to tame them. Asian elephants are an endangered species and capturing them from the wild has been a major contributor to this decline. According to one estimate, nearly one in three Asian elephants lives in captivity. And training an 8,000-pound wild animal to walk peacefully through crowded streets involves a lot of physical punishment. .[Source: Brent Stirton, National Geographic Podcats, April, 25, 2023]

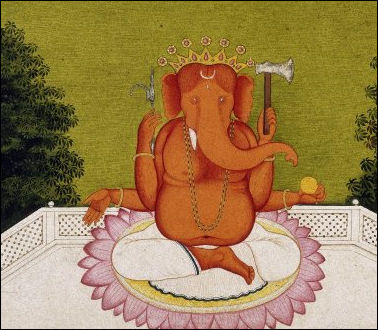

Sangita Iyet, a documentary filmmaker and advocate for Asian elephants who made the film film “Gods in Shackles” (2016), told National Geographic: Elephants are considered a cultural icon in India. Elephants were used in warfare in ancient times. The more the elephants they had, the more power they had. Additionally, in India, elephants are revered because they are considered the embodiment of Lord Ganesha. Lord Ganesha is a Hindu god with an elephant face. Because of that reverence, elephants had always been considered holy. That’s the tragic paradox because on the one hand, elephants are revered and worshiped. And on the other hand, they’re enslaved. They’re not only enslaved, but they’re deprived of the basic necessities.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ASIAN ELEPHANTS IN SRI LANKA factsanddetails.com

ASIAN ELEPHANTS: CHARACTERISTICS, NUMBERS, NATURAL DEATHS factsanddetails.com

ASIAN ELEPHANT BEHAVIOR: MUSTH, MOURNING AND DRUNKENNESS factsanddetails.com

ASIAN ELEPHANTS AND HUMANS: HISTORY, ROYALTY AND POLO factsanddetails.com

WORKING ELEPHANTS IN ASIA: LOGGING, TREKKING, ETHICALITY factsanddetails.com

ASIAN ELEPHANT PESTS: CROPS, DETERRENCE, HUMAN DEATHS factsanddetails.com

Asian Elephant Numbers and Range in India

According to the last elephant census in 2017, India has close to 30,000 wild elephants — around 60 percent of all wild Asian elephants. About 21 percent of them are in Assam. There are about 2,500 captive elephants. [Source: Meryl Sebastian — BBC News, Kochi, May 1, 2023]

In 2010, India's wild elephant population was estimated to be about 26,000. In addition there are about 3,600 domesticated elephants. India’s wild elephant population is spread across 18 states but 85 percent are found in the northeast and the south. About half of India's wild elephants are found in Assam and the northeast. Assam alone is home to about 5,000 elephants. There are also large numbers of domesticated elephants there. They have traditionally been used to pull logs out of the forest and load them on trucks.

India is home to a quarter to a third of Asia's elephants, which is amazing when you consider there are over 1 billion people in the country. Ganesh, the elephant headed son of omnipotent Siva, is the most called upon of all Hindu Gods. He is the one that takes care of the trials and tribulation of everyday life. In Indian culture, elephants are revered like gods. But in reality, many temple elephants endure much reported abuse, which animal welfare advocates are bringing to the public’s attention.

The number of elephants in India dropped from around 100,000 in 1900 to 19,000 in 1989. The decrease was mainly the result of poaching and loss of habitat. Elephants were declared and endangered species in 1977 and their capture was banned in 1981. The number of elephants in India increased from 19,000 in 1989 to 25,000 in 1993. Elephants rarely breed in captivity. Wild herds are the prime source of domesticated elephants. In India many come from the Mikir Hills in Assam.

Websites and Resources: Save the Elephants savetheelephants.org; International Elephant Foundation elephantconservation.org; Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; BBC Earth bbcearth.com; A-Z-Animals.com a-z-animals.com; Live Science Animals livescience.com; Animal Info animalinfo.org ; World Wildlife Fund (WWF) worldwildlife.org the world’s largest independent conservation body; National Geographic National Geographic ; Endangered Animals (IUCN Red List of Threatened Species) iucnredlist.org

Ganesh

Ganesh Ganesh is the Hindu elephant-headed god of prosperity, wisdom, success, intelligence and good luck. Very popular, particularly in Bombay and southern and western India, he is known as the creator and remover of obstacles, bestower of happiness and the eliminator of sorrow. Hindus pray and make offerings to him before beginning a journey, buying a house, starting a performance or launching a business venture. Even other gods pay tribute to him before they engage in any kind of activity so he can remove obstacles.

Ganesh is the son of Shiva and Parvati. Believed to have evolved from a fertility god, he is often depicted with a huge pot belly, slightly dwarfish, sitting like a Buddha or riding on a five -headed cobra or a rat. He has two or four arms. In one hand he carries rice balls, or sweetmeats (he is fond of eating and especially loves sweets). In another he holds broken pieces of his tusks, with which it said he inscribed the Mahabharata as the sages dictated it to him. Sometimes his trunk rests in a bowl that he hold in one of his hands. Sometimes he carries a trident to indicate his link to Shiva. Other times he carries a noose or an elephant goad. Ganesh’s association with rats comes from the ability of rats to gnaw through anything and remove obstacles.

Ganesh is often the god that people pray for help with their everyday problems. National Geographic nature photographer Frans Lanting wrote that in India: “Statues of Ganesha re everywhere — on car dashboards and in homes. Because of their connections to Ganesh, some people even treat wild elephants that raid their crops with respect. Farmers have even prostrated themselves before a rouge elephant instead of running it off.”

The are several stories explaining how Ganesh obtained his elephant head. According to one he attempted to block Shiva from entering a room where Parvati was bathing. Shiva was angered by this and chopped off Ganesh’s human head. After Parvati made a fuss, Shiva replaced the head with the head of the next animal he saw, which happened to be an elephant.

See Separate Article: GANESH: STORIES, WORSHIP AND POPULARITY factsanddetails.com

Catching Wild Elephants in Assam

In Assam two mahouts ride on a “koonkie”, or trained elephant. On rides on the neck with a lasso to capture wild elephants. the other stands on the elephants rump prodding it on with jabs from a metal spear. The mahouts hope to lasso a young elephant separated from its herd. But this easier said than done. Females carefully guard their young and large male tuskers, capable of tearing apart a trained elephant charge any intruders.

Describing the capture of young 13-year-old male elephant Paul Watson wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “With two of his “mahouts” riding trained elephants to block the flanks, Rabba pursued his quarry on the back of an elephant he caught 30 years ago..They chased the younger male for about an hour. When the tired animal stopped to eat, Rabbha quickly roped him.”

“His team of three elephant dragged him about three miles. They bound his legs and neck with heavy ropes of sisal fiber and lashed him to three eucalyptus trees, They ropes were wrapped six times around each hind leg and tied back to a 45-degree angle, forcing most of the trapped elephant’s enormous weight forward. Day and night, he is always off balance.”

See Separate Article: CATCHING WILD ASIAN ELEPHANTS factsanddetails.com

Working Elephants in India

in Jaipur

Today there are a few thousand working elephants left. They live mostly in wildlife parks, temples or urban colonies for working animals. About 40 percent of the domesticated elephants in India are employed in the logging industry. Others are used in tourism, religious ceremonies, circuses and begging. A domesticated elephant is worth about $4,000. If necessary they can be transported from place to place in trucks or trailers pulled by trucks.

Many working elephants in India make a living leading processions at festivals and carrying the bride and groom at weddings and working at an occasional government ceremony. Their lives have their ups and downs. One moment they are the center of attention, painted in bright colors and showed with flower pedals. The next they are chained to a railing. [Source: Pamela Constable, Washington Post, May 5, 2000]

The elephants earn about $120 to $170 per job for festivals and weddings. This is weighed against the costs of maintaining, transporting and feeding the animals. Each animal consumes about 100 pounds of hay a day. For energy on tough day they are given jaggery (cane molasses) for energy. In Assam, elephant employed in logging and transportation earned about $900 a month and cost between $175 to $259 a month to maintain.

Owners of working elephants ride them through traffic, bath them in local rivers and sleep next to them. They give their animals affection nicknames and the treat their ailments with "homemade concoctions handed down through generations." The elephants are often quite affectionate towards their owners and handlers, hugging them with their trucks when they come near. Sometime kumkie females will mate with wild tuskers. One mahout helper who went looking for a female that had wandered off was trampled to death by a wild male.

One owner told the Washington Post, "It was my forefathers who were really fond of elephants. They worked with them on royal estates, they went to war on them, they loved them. For me, it is a business. I like being part of a family tradition, but I do it because I am not educated to do anything else.”

Festival and Temple Elephants in Kerala, India

Kerala is home to about a fifth of India’s roughly 2,500 captive elephants. Thrissur Pooram, a festival in Kerala in India, attracts thousands of people and dozens of musicians, but by by far the stand out performers of the celebration are the elephants. They are covered in golden decorations and flowery necklaces as they parade through the crowded streets of the festival. In Kerala, there are a lot of captive elephants. You see elephants in churches and mosques as well as Hindu Temples

In Kerala elephants India are leased out to temples and festivals. Filmmaker Sangita Iyet told National Geographic: The minute they arrive into the temple, the first thing they do is decorate them with all these garlands and bells, and even the shackles are decorated. And then the deity’s idol will be mounted on the elephant’s back. And plus, there are about three or four men sitting atop the elephant. Overall, a total of about 300 to 400 kilos. And then they are forced to circle around the temples three or four times with the music and trumpets and drum beats that are so disturbing because elephants have such sensitive hearing. Plus, don’t forget the firecrackers. They live peacefully in the forest. What a stark contrast. [Source: Brent Stirton, National Geographic Podcats, April, 25, 2023]

There’s this one particular elephant called Thechikottukavu Ramachandran. He is a superstar. Elvis Presley would have loved to receive this kind of welcome, frankly. As soon as he steps out of the temple, people go crazy. They yell and shout and scream. And at the same time, you see his handler poking and prodding his very sensitive trunk so he salutes everybody. They don’t even notice how painful this ankush — or the bullhook — is. At ten and a half feet tall, the elephant Thechikottukavu Ramachendran could easily be the largest captive elephant in India. Because of his size, he has traditionally opened the largest festival of the year in the Indian state of Kerala.

But controlling such a large animal can be challenging. Over the years, Ramachendran’s handlers lost control of the animal. He has killed at least 11 people and attacked other elephants. After one of these attacks, the subsequent punishment from his handler left him blind in his right eye. Although he’s been occasionally banned from festivals after these incidents, he still performs today.

Urban Elephants and Unemployed Elephants in India

There were 23 working elephants left in New Delhi as of the early 2000s. Most of them lived with the their owners along the Yamana river in the shantytown of Guatampuri, where camels, water buffaloes and prized white horses are kept.

To get to jobs in Delhi the elephants often make their way through honking cars and reckless scooter rickshaw drivers on busy downtown streets. To get to jobs further away they are packed in the back of trucks and often have to endure long, grueling rides on bumpy roads standing up. They can not sleep during the long rides because they need familiar surroundings to relax.

Describing the difficulty of getting a young elephant into a cargo truck, Pamela Constable wrote in the Washington Post, "With a bellow she backed out, dragging six men with here. Prodding and cajoling, they pushed her back in. The frightened youngster bellowed again and burst from the truck. This time the men chained all of her feet and inched here forward, hitting and jabbing until she was tied inside. At the same time, they laughed and called her nicknames. After the ordeal was over, a mahout rubbed her trunk and kissed her."

In Assam, elephants and their owners were hit hard by a 1996 ban on illegal felling of trees. Elephants that earned $900 a month were lucky to make that much a year. Their primary jobs after the ban has been clearing bush at tea plantation and uprooting trees. Elephant owners have pleaded with the government to come up with works schemes for their animals. In response local government officials have been trying to generate an interest in elephant trekking. Elephant owners would like to work as forest guards patrolling for illegal logging and poaching.

In August, 1997, northeastern India, elephants, carrying signs in their trunks, went on strike to protest the logging ban that put them of work. The ban was part if effort to combat deforestation. In Assam, owner are struggling to provide and food and upkeep for their animals. If an elephants get injured it is not uncommon for the animal to die from infection because its owner can not afford the necessary medical care.

Captive Elephant Ban in India

In 2003, the practice of buying elephants was banned in India. According to National Geographic: Today officially owning an elephant requires a certificate showing that it was captured before then. The law isn’t bulletproof. People still capture and trade elephants illegally, but overall the law appears to be working. [Source: Brent Stirton, National Geographic Podcats, April, 25, 2023]

The population of captive elephants is decreasing. It’s estimated that there were about 1,000 captive elephants in Kerala in 2010, and there are fewer than 500 elephants today. However, that reduction is painful. The extra demand is causing current elephants to be over stressed as they are booked in more and more festivals. And those elephants, legal or not, frequently die before their natural lifespan.

Sangita Iyet told National Geographic: There are absolutely no religious scriptures, no Hindu or Islamic or Christian scriptures that suggest that you need to use elephants to make gods happy. I have really been researching that for a very long time. And indeed, there are so many Indian priests who are speaking out against the use of elephants because they clearly understand that this has nothing to do with culture or religion, but rather to do with profit and maintaining their status quo. So that’s what this is all about. So this has nothing to do with theology or religion or culture. This has everything to do with profit and commercialization.

Making Elephant Dung Paper in India

elephant poop

Reporting from Jaipur, India, Mark Magnier wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Vijender Shekhawat's big break came while visiting a shrine near the Amber Fort in Jaipur, as he glanced down at the pile of elephant dung he had just failed to avoid. A struggling maker of handmade paper, he noticed that the texture of the plant-eating animal's manure was a lot like wood pulp. Eureka! he thought. Pachyderm poop paper. [Source: Mark Magnier, Los Angeles Times, March 03, 2011]

His principal buyer was skeptical. "This is too strange," Mahima Mehra, head of papermaker Papeterie Co., recalls thinking. "It's bizarre." But Shekhawat persevered despite early failures. At 100 percent dung, the paper didn't hold together. At 50 percent dung and 50 percent cotton, it was too brittle. After many months, he settled on a 75 percent dung-25 percent cotton mix and he was on his way. (Don't worry; the dung is washed first.) Mehra also warmed to the idea after researching it and finding that it was made in Thailand, Sri Lanka and South Africa, among other places.

To counter cynics, they referenced Ganesha, an elephant-headed Hindu god, arguing that there was no harm in recycling divine waste. "Religion runs everything in this country," Mehra said. "Suddenly, scores of people wanted to work with the stuff."Shekhawat's next challenge was securing enough droppings. Sure, 4-ton behemoths produce hundreds of pounds of excrement a day. But the giants aren't exactly on every corner, no matter what the Incredible India campaigns suggest. Fortunately, tourist-friendly Jaipur, the capital of the northwestern state of Rajasthan, is a magnet for elephants and their mahouts, or caretakers, keen to overcharge foreigners for a ride. Shekhawat initially collected the dung wherever he could find it, but soon the wily mahouts realized that their once-worthless waste now held value. Paying them became prohibitive. So Shekhawat altered course. He provided the elephants' food, pleasing the mahouts. The beasts ate better, pleasing the elephants. And higher-quality dung emerged, pleasing Shekhawat. "Before, keepers skulked around dumping it at night," Shekhawat said. "Now they're delighted."

His partner, the New Delhi-based Mehra, initially entrusted the marketing to a German company, which featured the paper at a trade show. That flopped. Being, well, German, she figures, they approached things a bit too seriously. "You can't be stodgy, you gotta have some fun with this stuff," she said. "We decided to market it ourselves." "Made from the finest elephant dung in India," the earthy packaging boasts for Haathi Chaap, or "elephant print," brand products. "It's unique," said Tanvi Sharma, 26, buying an elephant-poo board game. "Then again, I just paid $8 for animal [dung]."

Reactions have exceeded expectations, Mehra said. "A few say 'eek' and refuse to touch it," she said. "But most laugh and, almost without thinking, smell it." (There's no discernable smell.) "Once we explain how it's made, they quite like the idea." Although business is going well, Shekhawat hasn't had it easy. In the beginning, he spent a lot of time knocking on doors, trying unsuccessfully to sell handmade cotton paper. Just as hopelessness set in, he met Mehra. The quality wouldn't cut it, she said, but she lent him bus fare, gave him some samples and promised deals if he picked up his game. A few weeks later, he returned with paper that was higher quality than her samples.

Shekhawat, who believes he was India's first elephant dung papermaker when he launched the venture eight years ago, uses 3,300 pounds of droppings a week. The dung is first washed, then boiled with baking soda and salt to reduce the smell, beaten to a pulp, forced through a sieve and flattened into sheets. Drying takes a day to, during rainy season, a week. At one point, Shekhawat fed the elephants turmeric hoping to create yellow paper. That failed. Now he adds organic dyes late in the process, including beet juice for red paper, dried pomegranate skins for gray and the castor oil plant for green. He now produces 2,000 2-by-3-foot sheets a week, which sell as far afield as the United States and Europe. "Call it God or good luck, a lot fell into place and I feel blessed," he said. "Before, they thought I was a bit of a fool. Now they think I'm a genius."

Indian-Made “The Elephant Whisperers” Win Oscar for Short Documentary in 2023

In 2023, “The Elephant Whisperers” made history by becoming the first Indian documentary to win an Oscar. The BBC reported: The documentary tells the story of an indigenous couple named Bomman and Bellie as they care for an orphaned baby elephant. The film explores the precious bond between the animal and his caretakers. In her acceptance speech, director Kartiki Gonsalves said, "I stand here today to speak of the sacred bond between us and our natural world, for the respect of indigenous communities and empathy towards other living beings we share space with, and finally, coexistence." [Source: BBC, March 13, 2023]

Shot in the Theppakadu Elephant Camp inside the Mudumulai Tiger Reserve in the southern state of Tamil Nadu, The Elephant Whisperers follows Bomman and Bellie as they care for Raghu, an injured baby elephant who gets separated from his herd. Later, Belli is also given the responsibility to care for Ammu, a female elephant calf.

The couple belong to the Kattunayakan community, a tribal group that has been protecting the forest for generations. Once they begin living together as a family, the humans and animals forge a close bond. When Raghu reaches adolescence, the state's forest department takes him away and places him with another caretaker who is more experienced in handling elephants in this life stage. The couple are heartbroken and miss Raghu deeply.

The documentary is permeated with moving scenes that capture the love and devotion the elephants and their human caretakers have for each other. In one scene, baby elephant Ammu wipes away Bellie's tears when she breaks down over Raghu's separation. Reacting to the Oscar win, Bomman told BBC Tamil that though they were happy about the award, "we are sad that Raghu is not with us now".

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2024