ORANGUTAN SPECIES

Classified in the genus Pongo, orangutans were originally considered to be one species. In 1996, they were divided into two species: 1) the Bornean orangutan (P. pygmaeus, with three subspecies) and 2) the Sumatran orangutan (P. abelii). A third species, the Tapanuli orangutan (P. tapanuliensis), was identified definitively in 2017. [Source: Wikipedia]

Sumatran orangutans and Bornean orangutans were officially recognized as distinct species in 2001 based on mitochondrial DNA analysis. Tapanuli orangutan (P. tapanuliensis), a small group that lives in southern Sumatra, was previously regarded as Sumatran orangutans. There were declared a unique species based on a combination of small morphological differences like skull size, first molar size, hair texture and genomic diversity. The morphological and behavorial differences between Sumatran orangutans and Bornean orangutans are more apparent, with Bornean orangutans (Bornean orangutans) coming to the ground less frequently than Sumatran orangutans and having more fatty flanges in the adult males. [Source: Alexander Hey, Animal Diversity Web (ADW)]

There is significant genetic differences between the species. Part of the second chromosome on one species is flipped in relationship to the second chromosome of the other. The population in southwestern Borneo, some scientists say, is different enough from others found elsewhere on the island to warrant classifications into a fourth species.

RELATED ARTICLES:

ORANGUTANS: CHARACTERISTICS, HISTORY, FOOD factsanddetails.com

ORANGUTAN BEHAVIOR: COMMUNICATION, CULTURE, SEX, MURDER factsanddetails.com

ORANGUTAN INTELLIGENCE: TOOLS, LEARNING, IPADS factsanddetails.com

ORANGUTANS AND HUMANS: PETS, TROUBLEMAKERS, FREEDOM factsanddetails.com

ENDANGERED ORANGUTANS: FIRES, POACHING AND PALM OIL factsanddetails.com

ORANGUTAN CONSERVATION AND REHABILITATION factsanddetails.com

BIRUTÉ GALDIKAS: HER LIFE, WORK AND ORANGUTANS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; BBC Earth bbcearth.com; A-Z-Animals.com a-z-animals.com; Live Science Animals livescience.com; Animal Info animalinfo.org ; World Wildlife Fund (WWF) worldwildlife.org the world’s largest independent conservation body; National Geographic National Geographic ; Endangered Animals (IUCN Red List of Threatened Species) iucnredlist.org

History Orangutan Species and Subspecies

Tapanuli orangutans are the oldest species of orangutan, diverging about 3.38 million years ago. About 674,000 years ago, genetic modeling indicates, Sumatran and Bornean populations split. Tapanuli orangutans live south of Lake Toba on Sumatra. Surprisingly, they are more closely related to Bornean orangutans than Sumatran ones.

During the ice ages when sea levels were low Borneo and Sumatra were connected to the Asian mainland. Around 20,000 years ago the Ice-Age-caused land bridges between Sumatra and Borneo were covered up by rising sea water as the Ice Age ended. The genetic evidence seems to indicate the species were separate hundreds of thousands of years before that. Fossil evidence also indicates that orangutans once lived in southern China, northern Vietnam, Laos and Java and were there until relatively recently.

There are three Bornean orangutan subspecies: 1) The Northwest Bornean orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus pygmaeus), in Sarawak (Malaysia) and northern West Kalimantan (Indonesia); 2) the Central Bornean orangutan (P. p. wurmbii), in – Southern West Kalimantan and Central Kalimantan (Indonesia); and 3) the Northeast Bornean orangutan (P. p. morio, black Borneon orangutans), in East Kalimantan (Indonesia) and Sabah (Malaysia).

Difference Between the Orangutan Species

It is not easy to tell the species apart. The most pronounced difference is between adult males. Bornean males tend to have larger cheek pads, rounder faces and darker fur while Sumatran males have more whiskers around their cheeks and chins and curlier, more matted hair on their body. The Bornean orangutans are slightly larger than the Sumatran variety.

Sumatran orangutans having a less broad face and are slightly lighter than Bornean orangutans. One of the biggest differences between the two is the shape and texture of the male cheek flanges (pads). According to Animal Diversity Web: Male orangutans possess cheek flaps later in development as a form of sexual selection, with bigger flanges indicating a more successful mate. Sumatran males are noted to have a diamond like shape of their flanges, with tufts of short yellow or white hair. Bornean counterparts have a more square shape of the flanges, developing more laterally and rounded. It has few hairs and wrinkles the brow and creases the nose, giving Bornean males a mostly grumpy appearance. [Source: Alexander Hey, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

According to Animal Diversity Web: Most studies have focused on the behavioral differences between the two regional populations of orangutans on Borneo and Sumatra. Most orangutan offspring learn all of their behaviors from their mother, including tool use. Interestingly, research has found that different populations of orangutan display different behaviors based off of their geographic region, an indication of a culture. Roof building of nests (to stop rain) was observed in Borneo, but not on Sumatra. There were other behaviors, like covering yourself in leaves to protect from the sun, that were observed in some of the populations on Borneo and Sumatra, but not all. [Source: Alexander Hey, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Orangutans on the island Sumatra have generally been observed using tools more than that of Borneo. These orangutans are known to use sticks to poke out insects from trees and leaves to hold fruits with spines, as well as many others. Bornean orangutans are generally more social, and thus in captivity, have learned a variety of behaviors from orangutans and humans that are obviously not their species or direct mother. They have been known to make paintings in captivity as well as learn sign language, or associate specific signs with specific human meanings. Rehabilitating orangutans in Tanjung National Park in Kalimantan were seen imitating human behavior like clothes washing, teeth brushing, hammering nails, and voluntarily riding in boats. /=\

Bornean Orangutans

Bornean orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus) generally live in swampy and hilly tropical rainforests of Borneo at elevations from sea level to 1000 meters (3281 feet) at an average elevation of less than 500 meters. They have a patchy distribution throughout the island and are completely absent from the southeast region at least in part because of logging and the destruction and conversion of tropical forest to agricultural land has decreased their habitat dramatically.. Fossil evidence suggests that Bornean orangutans were once widespread throughout Southeast Asia and evenly distributed across the entire island of Borneo.[Source: Benjamin Strobel, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Bornean orangutans are arboreal (live mainly in trees), and rarely descend to the ground. They prefer the old growth forests, including those in lowland swampy areas and dipterocarp forests, but are also found in secondary forests. The peat swamps and flood-prone dipterocarp forests produce more fruit than the dry dipertocarp forests and have a higher density of Bornean orangutans. Bornean orangutans are long lived like many of the other great ape species. Their lifespan in the wild is as high as 50 years. Their lifespan in captivity is as high as 59. The average lifespan for females is 57.3 years in captivity and 59 in the wild. The average lifespan for males is 58.8 years in captivity and 35 in the wild. [Source: Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research]

About 120,000 orangutans are left in the wild, with about 85 to 90 percent of them on Borneo. A 2016 study estimated the population of Bornean orangutans estimated that 104,700 Bornean orangutans lived the in the wild, significantly more than the in 14,613 Sumatran orangutans and 800 Tapanuli orangutans. The only predator of Bornean orangutans are humans. Even hunting for traditional purposes at a two percent hunting rate, is not sustainable for the current population of orangutans. Bornean orangutans are not threatened by natural predators with the exception of clouded leopards occasionally taking young Bornean orangutans.

On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List Bornean orangutans are listed as Endangered. On the US Federal List they are classified as Endangered. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix I, which lists species that are the most endangered among CITES-listed animals and plants. Bornean orangutans have the highest density in areas where there is valuable timber such as the peat swamps. Bornean orangutans have lost as much 80 percent of this habitat by some estimates. These forests have been illegally logged and legally logged and replaced with palm oil plantations.

Bornean Orangutan Characteristics and Feeding

Bornean orangutans on average weigh 87 kilograms (191.63 pounds) and have an average body and head length of 97 centimeters (38.19 inches). Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. Ornamentation is different. Both sexes have throat pouches for calling but the male’s throat pouches is larger than the females. Males having an average height of 97 centimeters and weight of 87 kilograms. Females have an average height of 78 centimeters and weight of 37 kilograms. Males also develop large cheek pads known as flanges and develop a sagittal crest where large temporal muscles attach. [Source: Benjamin Strobel, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

According to Animal Diversity Web: Bornean orangutans are distinguishable from their Sumatran cousins in their morphology. After diverging 1.5 million years ago, Bornean orangutans have become heavier and thicker, have darker red coats, long course hair, and the males have larger flanges covered in bristly hair and larger throat pouches.

Bornean orangutans are frugivorous (fruit eating), and spend two to three hours in the morning feeding avidly. Their diet consists of forest fruits, leaves and shoots, insects, sap, vines, spider webs, bird eggs, fungi, flowers, barks, and occasionally nutrient rich soils. Bornean orangutans have been documented eating more than 500 plant species as part of their diet. Fruits make up more than 60 percent of their total dietary intake and they will migrate depending on fruit availability.

Bornean Orangutan Behavior and Communication

Like the other orangutan species, Bornean orangutans are arboreal (live mainly in trees), diurnal (active during the daytime), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), solitary, territorial (defend an area within the home range), and have dominance hierarchies (ranking systems or pecking orders among members of a long-term social group, where dominance status affects access to resources or mates). /=\

Bornean orangutans rarely come down from the trees. The size of the range territory of adult males is two to six square kilometers. Their home ranges often incorporate multiple female home ranges. When a young female is establishing her home range, she will often choose a range nearby or bordering her mother's range. [Source: Benjamin Strobel, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

According to Animal Diversity Web: Small groups of females may travel with their infants in search of food, but adult males are usually solitary. While all Bornean orangutans are generally solitary they may have occasional social connections. Groups of six or more Bornean orangutans are rare but can be found during times of mast fruiting; when a group of trees suddenly fruit at the same time. Daily and seasonal movements change frequently and are influenced by the availability of fruit. Bornean orangutans use multiple methods of locomotion. Brachiation (swinging from tree limb to tree limb using their arms) is only seen in young orangutans whereas older orangutans walk quadrupedally (using all four limbs for walking and running), or occasionally bipedally. When walking quadrupedally they walk on their fists rather than their knuckles, unlike other great apes. Bornean orangutans sleep in nest platforms made of vegetation 12 to 18 meters (40 to 60 feet) off the ground. Food is plucked with the fingers and the palm due to their inability to use their thumbs. Bornean orangutans cannot swim which make rivers and other water sources impassable boundaries, limiting their range.

Bornean orangutans communicate with vision and sound and sense using vision, touch, sound and chemicals usually detected with smell. The most prominent form of communication for Bornean orangutans are the long-call, a one to two minute call performed only by flanged males. The long-call can be heard from several kilometers away in the right conditions. The main purposes of long-calls are to inform other males of the caller's presence (when unflanged males hear long-calls they flee the area) and to call out to sexually responsive females. Long-calls are spontaneous and do not follow any specific pattern. Some evidence suggests that the long-call can even suppress the development of unflanged males. When the unflanged males hear a long-call, stress hormones are produced which inhibit the development of the unflanged males. The other type of calling produced by Bornean orangutans are a fast-call, which is most often made after male-to-male conflict. In addition to the long and fast calls, Bornean orangutans smack their lips to produce sounds when in small social groups.

Bornean Orangutan Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Bornean orangutans are polygynous (males have more than one female as a mate at one time). They engage in year-round breeding and on average femals . Female orangutans breed every eight years. orangutans breed year-round. The average number of offspring is one. Dominant flanged males often have an established territory that encompasses multiple females' territories. The multiple females within the male’s territory copulate with him and produce his offspring. Younger unflanged males often cannot sustain a home range of their own and are forced to wander throughout the forests. When these small, wandering males come into contact with a female, the males sometimes force copulation. This is different from the flanged males which will long-call; a call to help receptive females locate him. Females prefer to mate with flanged males, which may be a way to ensure protection from unflanged males. [Source: Benjamin Strobel, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Benjamin Strobel wrote in Animal Diversity Web: Bornean orangutans do not have a breeding season, but females show higher ovarian function during periods of food abundance. Ovulation in Bornean orangutans occurs on the 15th day of a 30-day cycle. Copulation generally occurs with both parties hanging with their arms and facing each other.

The gestation period ranges from 233 to 263 days, with the average being 245 days. The age in which young are weaned ranges from 36 to 84 months. The average weaning age is 42 months and the age in which they become independent ranges from five to eight years, with the average being seven years. Females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at 5.8 to 11.1 years and males do so at eight to 15 years.

Female Bornean orangutans invest a lot of time in their offspring, taking care of them until they reach adolescence at around six years of age. Since Bornean orangutans are semi-solitary in nature, the males have very little contact and no investment in their young. From birth, the offspring will be in constant contact with the mother for four months and will be carried everywhere the mother goes. The offspring remains completely dependent upon the mother for the first two years of life. At about five years of age, the offspring will begin to make short trips on its own, usually staying within sight of the mother. Orangutan young may start to build their own nests as play, and eventually start sleeping in the nests they builds.

Young are nursed until age six and remain at the mother's side until the next birth. The offspring has contact with its mother after birth, but once female offspring start to display sexual behaviors, they begin traveling separately. Once the female offspring is separated from its mother completely, it will move off and establish a territory nearby its mother’s territory. Adolescence in Bornean orangutans starts at five years of age and lasts until around eight years of age. Male offspring remain socially immature despite being sexually mature. The young males avoid contact with mature males and start to wander the forests until they become a flanged male and establish their own resident territory. Female Bornean orangutans reach menopause around the age of 48 years.

Sumatran Orangutans

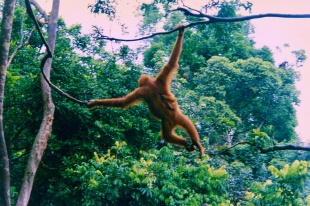

Sumatran orangutans (Pongo abelii) live on the island of Sumatra in Indonesia. Fossil evidence suggests that they once occurred throughout Sumatra and the island of Java but now they are restricted to the northern part of Sumatra in fragmented forests. Logging and palm oil agriculture has severely limited thei range. Sumatran orangutans are found in primary tropical lowland forests, including mangrove, swamp forests, and riparian forests at elevations of 200 to 1,500 meters (656 to 4921 feet). They prefer elevations between 200 to 400 meters, where the most fruiting trees occur, and spend almost all their time in trees, building nests to nap in and sleep in during the night. [Source: Kelle Urban, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Up until the 1990s, Sumatran and Bornean orangutans were considered the same species of Bornean orangutans. Their lifespan in the wild is 44 to 58 years. Females seem to be capable of giving birth up to 51 to 53 years old when they experience of menopause and. Male life spans are slightly longer that females. They are considered string and healthy late in life when based on the tightness of their cheek pads and absence of bald spots. A captive female Sumatran orangutan lived to 55 years at the Miami Zoo.

Of the 120,000 orangutans are left in the wild, only about 10 to 15 percent live on Sumatra. Estimates in the 2000s counted around 6,500 Sumatran orangutans. A 2016 study estimated the population of Sumatran orangutans in the wild was 14,613, twice the previous estimates. On the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List Sumatra orangutans are listed as Critically Endangered. On the US Federal List they are classified as Endangered. In CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild) they are in Appendix I, which lists species that are the most endangered among CITES-listed animals and plants. /=\

The main threats to Sumatran orangutans are habitat loss. By one estimate their habitat decreased over 80 percent in the 1990s and 2000. Hunting orangutans for meat and killing adult females to obtain infants for the illegal pet trade caused an estimated decline in the orangutan population of 30 to 50 percent in the 200s. Uncontrolled forest fires have also harmed orangutan habitat. The main natural predators are clouded leopards and Sumatran tigers, both of which can climb tree and don’t take many orangutans, but when they do they take young.

Sumatran Orangutan Characteristics

Sumatran orangutan range in weight from 30 to 90 kilograms (66 to 198 pounds) and range in length from 1.3 to 1.8 meters (4.3 to 5.9 feet). Sexual Dimorphism (differences between males and females) is present: Males are larger than females. Males and females have different shapes. Ornamentation is different. Female weights range from 30 to 50 kilograms and they can reach 1.3 meters tall. Male weights range from 50 to 90 kilograms and reach a height of 1.8 meters. Some old males may get too large to move around in trees easily and may have to resort to walking on the ground. [Source: Kelle Urban, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Sumatran orangutans are the largest non-human primates in Asia and the largest tree-living primates. They may be distinguished from Bornean orangutans by their longer fur, more slender build, white hairs on the face and groin, and long beards on both males and females. Sumatran orangutan have long, fine red hair on their bodies and faces. Males have large cheek pads that are covered in a fine white hairs. The arm span, from finger tip to finger tip, is 2.25 meters. The legs are small and weak compared to their muscular arms.

Sumatran orangutans are primarily frugivore (fruit eating) but are considered herbivores (primarily eat plants or plants parts) although they do eat the occasional eggs or insects. Among the plant foods they eat are leaves, wood, bark, or stems seeds, grains, and nuts fruit flowers. Most food choices are based on vary seasonally. Fruits generally are only available at certain times for short periods of time. Orangutans follow the fruiting season of local trees, feeding when they are ripe. Figs are particularly important and desired. During the dry season, when fruit is less available, Sumatran orangutans consume other kinds of vegetation. Annually, fruit makes up about 60 percent of their diet, with the remainder being young leaves (around 25 percent), flowers and bark (10 percent), insects, mainly ants, termites, and crickets (5 percent), and an occasional egg.

Sumatran Orangutan Behavior and Communication

Like all orangutans, Sumatran orangutan are arboreal (live mainly in trees), scansorial (able to or good at climbing), diurnal (active during the daytime), motile (move around as opposed to being stationary), nomadic (move from place to place, generally within a well-defined range), solitary, territorial (defend an area within the home range). The size of their range territory varies from five to 25 square kilometers. Males and females share overlapping home ranges. Females range from 500 to 850 hectares areas that overlap with each other. Male territories have a minimum range of 25 square kilometers and embrace up to three female territories.[Source: Kelle Urban, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Sumatran orangutans build new nests in trees each night in which to sleep. Nests are built with bent branches, sticks, and leaves. Young orangutans use brachiation (swinging from tree limb to tree limb using their arms) extensively, but older, larger orangutans tend to use hand over hand motion. Very large males spend more time the ground, perhaps because many trees cannot sustain their weight.

Sumatran orangutans are more social than Bornean orangutans, spending more time in small groups. According to Animal Diversity Web: Grooming is a major source of social interaction in most primates, but there are few grooming techniques used by Sumatran orangutans, which are more solitary. Females occasionally scratch and preen each other. Social grooming has only been documented on the upper part of the body. Mother-offspring grooming has only been seen in zoos. In this case, most mothers have to hold down their offspring once the young are capable of independent locomotion. They also cut toenails and fingernails with their teeth. Most mother-offspring grooming is done by mouth; hands are rarely used. When grooming, they normally use one finger, moving it in one direction. The same technique is used for itching, but the whole hand or arm is used. When self-grooming, orangutans flip through their hair with their lips and mouth. They only attend to areas they can see and reach. /=\

Play is either non-social or social and has been recognized in adults and juveniles. Juveniles exhibit a surprisingly high amount of playful interactions, such as non-aggressive biting. Actual contact is not always necessary, sometimes simple body language is used as play. Compared to all other great apes, orangutans are capable of the most facial expression, due to their very flexible lips. Sumatran orangutans are exceptionally intelligent and capable of learning complex tasks and language.

Male Sumatran orangutans are capable of long, exceptionally loud calls (called "long calls") that carry through forests for up to one kilometers. The "long call" is made up of a series of sounds followed by a bellow. These calls help males claim territory, call to females, and keep out intruding male orangutans. Males have a large throat sac that lets them make these loud calls. They may also pull small trees and limbs down to add a crashing sound along with the call. Sumatran orangutans vocalize with grunts, grumbles, and squeaks when they meet each other, and young orangutans squeak, bark and scream. Both adults and young make a variety of sounds with their lips and throats, including sucking, burping, and grinding their teeth.

Sumatran Orangutan Mating, Reproduction and Offspring

Sumatran orangutans are polygynandrous (promiscuous), with both males and females having multiple partners. They engage in seasonal breeding during the rainy seasons from December and May, with interbirth intervals of three to four years. The average number of offspring that is born is one. Most mating occurs in the heaviest fruiting months during the rainy season. There is large variability in the amount of fruit from season to season. Mast fruiting years, in which most of the trees of a single species fruit synchronously, occur every two to 10 years. Sumatran orangutan breeding is most intense in mast years. Any female that isn’t caring for offspring is available to mate. Females normally mate with the adult male whose large territory they live in, but chance encounters can happen in high fruiting seasons when many orangutans gather to feed. [Source: Kelle Urban, Animal Diversity Web(ADW) /=]

Kelle Urban wrote in Animal Diversity Web: The primary mating tactic involves "harassment" of female Sumatran orangutans by sub-adult males and adult males. Most harassment involves sub-adult males; females are less likely to mate with them, as compared to large adult males. Females are cornered by sub-adult males and may be raped by them; these sub-adult males may also take a female's young from her if they think it will make her more willing or available to mate. Female orangutans have learned strategic ways to avoid or reduce harassment. The first method is a social tactic, where females form non-mating parties with adult male orangutans that reside in their area, reducing attacks from sub-adult males. Another is female-female bonding, where females alone form alliances to protect themselves against sub-adult males. Harassment has also increased in the last decade due to habitat loss from illegal logging. More orangutans are forced into too small of an area, increasing agonistic interactions. /=\

The gestation period ranges from 227 to 275 days. The average weaning age is 48 months and the age in which they become independent ranging from eight to nine years and the average time to independence is 9.3 years. After a female orangutan has given birth, her next eight to nine years are devoted to her offspring's survival. Infant and juvenile orangutans must learn everything (feeding, social behaviors, etc.) from their mothers. Mothers provide young orangutans with food until they have learned to distinguish different types of food. Males do not play a role in offspring care. Once fully developed, a male will leave his mother to find his own territory. A developed, independent young female will either disperse or take up residence near her mother's territory. Females reach sexual or reproductive maturity at nine to 15.5 years, with the average being 12.3 years. Males reach sexual or reproductive maturity at 15 to 24 years, with the average being 19 years

Tapanuli Orangutans

The Tapanuli orangutan (Pongo tapanuliensis) was first described as a distinct species in 2017. They live in the Batang Toru area of South Tapanuli, which about 100 kilometers south of Lake Toba on Sumatra. The names tapanuliensis and Tapanuli come from Tapanuli, the hilly region in North Sumatra where the species lives. As of 2018, there are roughly 800 individuals of this species and it is currently on the critically endangered species list. [Source: Wikipedia]

An isolated population of orangutans in the Batang Toru area of South Tapanuli was reported in 1939. The population was rediscovered by an expedition to the area in 1997. These orangutans were identified as a distinct species, following a detailed phylogenetic study in 2017. The study analyzed the genetic samples of 37 wild orangutans from populations across Sumatra and Borneo and conducted a morphological analysis of the skeletons of 34 adult males. The holotype of the species is the complete skeleton of an adult male from Batang Toru who died after being wounded by locals in November 2013 and is stored in the Zoological Museum of Bogor. The skull and teeth of the Batang Toru male differ significantly from those of the other two orangutan species. Comparisons of the genomes of all 37 orangutans using principal component analysis and population genetic models also indicated that the Batang Toru population is a separate species.

Genetic comparisons show that Tapanuli orangutans diverged from Sumatran orangutans about 3.4 million years ago, and became more isolated after the Lake Toba supereruption that occurred about 75,000 years ago. They had sporadic contact with the other orangutan species until 10,000 to 20,000 years ago. Tapanuli orangutans diverged from Bornean orangutans about 674,000 years ago. Orangutans were able to travel from Sumatra to Borneo because the islands were connected by land bridges during ice ages when sea levels were much lower. The present range of Tapanuli orangutans is thought to be close to the area where ancestral orangutans first entered what is now Indonesia from mainland Asia.

Tapanuli orangutans live in tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests. The entire population of the species is found in an area of about 1,000 square kilometers (390 square miles) at elevations from 300 to 1,300 meters (980 to 4,300 feet). Tapanuli orangutans are separated from Sumatra’s other species of orangutan, the Sumatran orangutan, by just 100 kilometers (62 miles). The rarest great ape, Tapanuli orangutans are listed as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The animals have been threatned by of hunting, conflict with humans, the illegal wildlife trade, rampant habitat destruction for small scale agriculture, mining and a proposed hydroelectric dam, the Batang Toru hydropower project., in the area with the highest density of orangutans. which could impact up to 10 percent of its already dwindling habitat and degrade important wildlife corridors. Conservationists predict an 83 percent decline in three generations (75 years) if the necessary conservation measures and practices are not implemented. Inbreeding depression is likely due to the small population size and fragmented range. This is supported by the genomes of the two Tapanuli orangutan individuals, which show signs of inbreeding.

Tapanuli Orangutan Characteristics and Behavior

Tapanuli orangutans resemble Sumatran orangutans more than Bornean orangutans in body build and fur color but have frizzier hair, smaller heads, and flatter and wider faces. Dominant male Tapanuli orangutans have prominent moustaches and large flat cheek pads, known as flanges, covered in downy hair. As with other two orangutan species, males are larger than females; males are 1.37 meters (4½ feet) in height and weigh 70–90 kilograms (150–200 pound); females are 1.10 meters (3.7 feet) in height and weigh 40–50 kilograms (88–110 pound). When comparing the Tapanuli orangutan with the Sumatran orangutan, the Tapanuli orangutan has a deeper suborbital fossa (a depression in the skull that houses a part of the brain) and a facial profile that is more angled.

Tapanuli orangutan characteristic that are different from differs from the other two existing orangutan species (Sumatran orangutan and Bornean orangutan): 1)their upper canines are larger; 2) they have a shallower face depth; 3) their pharyngotympanic tube is shorter; 4) they have a shorter mandibular joint; 5) they have a narrower maxillary incisor row; 6) the distance across the palate at the first molars are narrower; 7) there is a smaller horizontal length between the mandibular symphysis; 8) they have a smaller inferior torus; and 9) the width of the ascending ramus located in the mandible.

The diet of Tapanuli orangutan differs from that of two other orangutan species as they eat things like caterpillars and conifer cones. Tapanuli orangutans are thought to be exclusively arboreal as scientists have not seen them descend to the ground in over 3,000 hours of observation. This is probably due to the presence of Sumatran tigers in the area.Their other main predators are Sunda clouded leopards, Sumatran dholes and crocodiles. Like other orangutan, Tapanuli orangutans have slow reproductive rates causing a problem in increasing population. The loud, long-distance call or 'long call' of male Tapanuli orangutans has a higher maximum frequency than that of Sumatran orangutans, and lasts much longer and has more pulses than that of Bornean orangutans.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2024