LIFE IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE

Ottoman women

The population of the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century was between 20 million and 30 million, roughly divided equally between the European, Asian and African parts of the empire. The population had expanded greatly in previous century as it had in Europe due to recovery from the Great Plague. In the 17th century, Istanbul had a population of around 700,000 and was considerably larger than the largest cities in Europe: Naples, Paris and London.

Under Ottoman rule, there was not the kind of cultural imperialism there was under early Arab rule. Turkish was the language of the sultan, his court, the military and the administrative elite. Arabic was the language of science, religion and law; Turkish was the language of poetry and secular works. Most everyone else spoke their local language. Local people largely kept their original religions and local customs.

Ottoman society basically had two tiers: 1) the privileged elite which was comprised of people connected to the government, wealthy merchants and traders, and large landowners: 2) and the masses which consisted mostly of rural peasants and urban poor. There wasn’t much of middle class, which was made up mostly of craftsmen and small time traders and merchants.

Social life was often centered around the bazaars and Turkish baths. Many people owned homes so the population was reasonably stable. Sometimes people of the same ethnic group or religion lived in their own quarters. Turbans and other headgear were an indication of rank and status in the Ottoman society.

Most Ottoman sultans married slaves. From the 16th century on no Ottoman sultan was married to a free woman.

Websites and Resources: Ottoman Empire and Turks: The Ottomans.org theottomans.org ; Ottoman Text Archive Project – University of Washington courses.washington.edu ; Wikipedia article on the Ottoman Empire Wikipedia ; Encyclopædia Britannica article on the Ottoman Empire britannica.com ; American Travelers to the Holy Land in the 19th Century Shapell Manuscript Foundation shapell.org/historical-perspectives/exhibitions ; Ottoman Empire and Turk Resources – University of Michigan umich.edu/~turkis ; Turkey in Asia, 1920 wdl.org ; Wikipedia article on the Turkish People Wikipedia ; Turkish Studies, Turkic republics, regions, and peoples at University of Michigan umich.edu/~turkish/turkic ; Türkçestan Orientaal's links to Turkic languages users.telenet.be/orientaal/turkcestan ; Turkish Culture Portal turkishculture.org ; ATON, the Uysal-Walker Archive of Turkish Oral Narrative at Texas Tech University aton.ttu.edu ; The Horse, the Wheel and Language, How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes shaped the Modern World", David W Anthony, 2007 archive.org/details/horsewheelandlanguage ; Wikipedia article on Eurasian nomads Wikipedia

Bursa and Cumalıkızık, Birthplace of the Ottoman Empire

According to UNESCO: “Located on the slopes of Uludağ Mountain in the southern Marmara region of the north-western part of Turkey, Bursa and the nearby village Cumalıkızık represent the creation of an urban and rural system establishing the first capital city of the Ottoman Empire and the Sultan’s seat in the early 14th century. In the empire’s establishment process, Bursa became the first city, which was shaped by kulliyes, in the context of waqf (public endowments) system determining the expansion of the city and its architectural and stylistic traditions. [Source: UNESCO =]

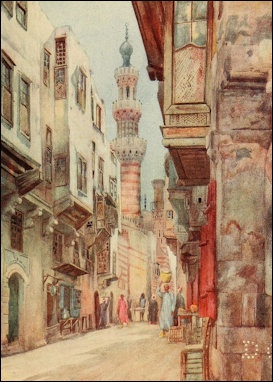

typical street in Cumalikizuk

“The site illustrates the creation of an urban and rural system establishing the Ottoman Empire and embodies the key functions of the social and economic organization of the new capital which evolved around a civic centre. These include commercial districts of khans, kulliyes (religious institutions) integrating mosques, religious schools, public baths and a kitchen for the poor, as well as the tomb of Orhan Ghazi, founder of the Ottoman dynasty. One component outside the historic centre of Bursa is the village of Cumalıkızık, the only rural village of this system to show the provision of hinterland support for the capital. =

“The specific development of the city emerged from five focal points, mostly on hills, where the five sultans (Orhan Ghazi, Murad I, Yıldırım Bayezid, Çelebi Mehmed, Murad II) established public kulliyes consisting of mosques, madrasahs (school), hamams (public baths), imarets (public kitchens) and tombs . These kulliyes, featuring as centres with social, cultural, religious and educational functions, determined the boundaries of the city. Houses were constructed near the kulliyes, turning into neighborhoods surrounding the kulliyes within the course of time. Kulliyes were also related with rural areas due to the waqf system. For example, the aim of Cumalıkızık as a waqf village, meaning that it permanently belonged to an institution (a kulliye), was to provide income for Orhan Ghazi Kulliye, as stated in historical documents. =

“The exceptional city planning methodology is expressed in the relationship of the five sultan kulliyes, one of which constitutes the core of the city’s commercial centre, and Cumalıkızık which is the best preserved waqf village in Bursa. This methodology developed during the foundation of the first Ottoman capital in early 14th century and expanded until the middle of the 15th century. =

Bursa and Cumalıkızık as Examples of Ottoman Urban and Rural Planning

According to UNESCO: “Bursa was created and managed by the first Ottoman sultans, through an innovative and ingenious system, which developed an unprecedented urban planning process. Using the semi-religious Ahi brotherhood organizations to run commercial life, and making the best use of the public endowment system Waqf (relating kulliyes and villages), they established kulliyes as nuclei providing all public infrastructure services prior to the creation of neighbourhoods. These centres allowed for the fast establishment of a vivid, sustainable new capital for one of the most rapidly expanding empires of the world. [Source: UNESCO =]

“Bursa, as the first capital of the Ottoman Empire, was of key importance as a reference for the development of later Ottoman cities. The new urban development approach introduced by the early Ottoman Sultans was based on the construction of public infrastructure complexes outside the existing city core surrounded by walls, and created a new town for non-urban population, which became the model Ottoman city, later referenced throughout the expansion of the Ottoman Empire. The new capital, with its social, religious and commercial functions reflects the values of the society and the values it accepted from its neighbours, during long years of migration from central Asia to the West. This is also reflected in the integration of Byzantine, Seljuk, Arab, Persian and other influences in architectural stylistics. =

“Bursa and Cumalıkızık illustrate the first capital of the Ottoman Sultans, rulers of an Empire reaching from Anatolia to Yemen and including parts of Europe and North Africa for hundreds of years, which developed a unique architectural plan called “Bursa style” or “inverted T plan”. In the first stage, the inverted T planned mosques, with guest rooms, were able to meet the functions of independent buildings such as public kitchen and madrasah, which were constructed in the complexes as separate buildings, in later stages. =

Bursa in 1895

“Kulliyes, as social units, meeting the requirements of the society and facilitating life, shaped the city by taking the multifunctional structure of this plan type as an example. In other words, the multifunctional inverted T plan is an exceptional building type which illustrates uniquely the city planning system in Bursa. These kulliyes, with their individual buildings constitute the urban nuclei of this system and characteristically shape the urban landscape of Bursa. While individual architectural components in Bursa can be considered as outstanding examples of architectural type, this criterion is met through the ensembles, created by these components (khans, bedesten, mosques, madrasahs, tombs, hamams, and houses). =

“Bursa is directly associated with important historical events, myths, ideas and traditions from the early Ottoman period. The mystic image of the city, created through the presence of the tombs of early Ottoman sultans and the famous Hacivat and Karagöz characters who were workers in the construction of the Orhan Ghazi Kulliye, retains close associations to early Ottoman life. Many sultans and courtiers, then the leaders of the Muslim World, recognized the importance of Bursa as the spiritual capital of the Ottoman Empire, even after the conquest of İstanbul and demonstrated their loyalty to their ancestors and the city, by choosing Bursa as the location for burial. =

“The village of Cumalıkızık in its agricultural landscape provides an overall perception of a high degree of authenticity. Few of the houses are used for other than residential purposes and the village seems to have retained a special atmosphere, providing an impression of earlier times. Several aspects, like the village pattern, the form and layout schemes applied in the houses, the materials used, in particular the local stone for the ground floor, wood for the upper floors and the typology of roofs, the agricultural fields and the general setting give an original impression despite some 19th century reconstructions and regular repairs which have been undertaken at other times. It is important for the preservation of the integrity of Cumalıkızık to ensure the continuous presence of the local inhabitants and avoid processes of intense commercialization.” =

Kulliye System

According to UNESCO: “The kulliye urban system allowed for the expansion of a newly built and established capital city in a short span of time. While the urban planning system is represented through the kulliyes as well as the commercial quarter which developed around one of the kulliyes, the residential neighbourhoods surrounding the kulliyes contributed to the process of urban expansion. [Source: UNESCO =]

Haseki kulliye

“The kulliyes continue to function as the focal points and public spaces of various residential neighbourhoods at present. Buildings in the Khans Area, which developed around Emir Khan around the Orhan Ghazi Kulliye in the historical commercial axis, still preserve their original commercial functions at present, however, Pirinç Han and Kapan Han were partially harmed due to the construction of new streets during construction activities in the 19th century. Furthermore, Cumalıkızık Village, with unique examples of civil architecture has sustained its rural character. =

“The Khans Area continues the tradesmen culture of the Ottoman era to date, including traditional rituals such as first sale of the day, bargaining, master-apprentice relations, and neighbourliness among tradesmen. The Khan’s courtyard plans have retained authenticity in form and design and have been effective for khans to sustain their commercial functions until the present. =

“In the kulliyes changes in use and function have occurred but are well documented. In Muradiye complex, for example, the public kitchen is used as a restaurant, and the hamam as a centre for physically-challenged people. In the Yesil complex the madrasah is now the Museum of Turkish Islamic Art. The kulliyes remain still focal points meeting the social, cultural and religious needs of the inhabitants, in accordance with their original public functions, and continue to reflect the Ottoman characteristics of Bursa. =

Courtyard House in Ottoman-Period Damascus

On a courtyard house in Ottoman-Period Damascus, Ellen Kenney of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “One entered the Damascene courtyard house from a plain door on the street into a narrow passage, often turning a corner. This bent-corridor arrangement (dihliz) provided privacy, by preventing passers-by in the street from viewing the interior of the residence. The passage led to an internal open-air courtyard surrounded by living spaces, usually occupying two floors and covered with flat roofs. Most well-to-do residents had at least two courtyards: an outer court, referred to in historical sources as the barrani, and an inner court, known as the jawwani. An especially grand house might have had as many as four courtyards, with one dedicated as the servants' quarters or designated by function as the kitchen yard. These courtyard houses traditionally housed an extended family, often consisting of three generations, as well as the owner's domestic servants. To accommodate a growing household, an owner might enlarge the house by annexing a neighboring courtyard; in lean times, an extra courtyard could be sold off, contracting the area of the house. [Source: Ellen Kenney, Department of Islamic Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Kenney, Ellen. "The Damascus Room", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2011, metmuseum.org \^/]

Maktab courtyard house in Damascu

“Almost all courtyards included a fountain fed by the network of underground channels that had watered the city since antiquity. Traditionally, they were planted with fruit trees and rosebushes, and were often populated by caged song-birds. The interior position of these courtyards insulated them from the dust and noise of the street outside, while the splashing water inside cooled the air and provided a pleasant sound. The characteristic polychrome masonry of the walls of the courtyard's first story and pavement, sometimes supplemented by panels of marble revetment or colorful paste-work designs inlaid into stone, provided a lively contrast to the understated building exteriors. The fenestration of Damascus courtyard houses was also inwardly focused: very few windows opened in the direction of the street; rather, windows and sometimes balconies were arranged around the walls of the courtyard (93.26.3,4). The transition from the relatively austere street façade, through the dark and narrow passage, into the sun-splashed and lushly planted courtyard made an impression on those foreign visitors fortunate enough to gain access to private homes - one 19th century European visitor aptly described the juxtaposition as "a gold kernel in a husk of clay."

“The courtyards of Damascus houses typically contained two types of reception spaces: the iwan and the qa'a. In the summer months, guests were invited into the iwan, a three-sided hall that was open to the courtyard. Usually this hall reached double-height with an arched profile on the courtyard façade and was situated on the south side of the court facing north, where it would remain relatively shaded. In the winter time, guests were received in the qa'a, an interior chamber usually built on the north side of the court, where it would be warmed by its southern exposure.” \^/

Room in Ottoman-Period Courtyard House in Damascus

“On a residential reception chamber (qa'a) in a late Ottoman courtyard house in Damascus, Ellen Kenney of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The highlight of the room is the splendid decorated woodwork installed on its ceiling and walls. Almost all of these wooden elements originally came from the same room. However, the exact residence to which this room belonged is unknown. Nevertheless, the panels themselves reveal a great deal of information about their original context. An inscription dates the woodwork to A.H. 1119/1707 A.D, and only a few replacement panels have been added at later dates. The large scale of the room and the refinement of its decoration suggest that it belonged to the house of an important and affluent family. [Source: Ellen Kenney, Department of Islamic Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Kenney, Ellen. "The Damascus Room", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2011, metmuseum.org \^/]

space near a fountain in Maktab Anber

“Judging from the layout of the wooden elements, the museum's room functioned as a qa'a. Like most Ottoman-period qa'as in Damascus, the room is divided into two areas: a small antechamber ('ataba), and a raised square seating area (tazar). Distributed around the room and integrated within the wall paneling are several niches with shelves, cupboards, shuttered window bays, a pair of entrance doors and a large decorated niche (masab), all crowned by a concave cornice. The furnishing in these rooms was typically spare: the raised area was usually covered with carpets and lined with a low sofa and cushions. When visiting such a room, one left one's shoes in the antechamber, and then ascended the step under the archway into the reception zone. Seated on the sofa, one was attended by household servants bearing trays of coffee and other refreshments, water pipes, incense burners or braziers, items that were generally kept stored on shelves in the antechamber. Typically, the shelves of the raised area displayed a range of the owner's prized possessions - such as ceramics, glass objects or books - while the cupboards traditionally contained textiles and cushions.\^/

“Ordinarily, the windows facing the courtyard were fitted with grills as they are here, but not glass. Shutters snugly mounted within the window niche could be adjusted to control the sunlight and airflow. The upper plastered wall is pierced with decorative clerestory windows of plaster with stained glass. At the corners, wooden muqarnas squinches transition from the plaster zone to the ceiling. The 'ataba ceiling is composed of beams and coffers, and is framed by a muqarnas cornice. A wide arch separates it from the tazar ceiling, which consists of a central diagonal grid surrounded by a series of borders and framed by a concave cornice.\^/

“In a decorative technique very characteristic of Ottoman Syria known as 'ajami, the woodwork is covered with elaborate designs that are not only densely patterned, but also richly textured. Some design elements were executed in relief, by applying a thick gesso to the wood. In some areas, the contours of this relief-work were highlighted by the application of tin leaf, upon which tinted glazes were painted, resulting in a colorful and radiant glow. For other elements, gold leaf was applied, creating even more brilliant passages. By contrast, some parts of the decoration were executed in egg tempera paint on the wood, resulting in a matte surface. The character of these surfaces would have constantly shifted with the movement of light, by day streaming in from the courtyard windows and filtering through the stained glass above, and by night flickering from candles or lamps.\^/

“The decorative program of the designs depicted in this 'ajami technique closely reflects the fashions popular in eighteenth-century Istanbul interiors, with an emphasis on motifs such as flower-filled vases and overflowing fruit-bowls. Prominently displayed along the wall panels, their cornice and the tazar ceiling cornice are calligraphic panels. These panels bear poetry verses based on an extended garden metaphor - especially apt in conjunction with the surrounding floral imagery - that leads into praises of the Prophet Muhammad, the strength of the house, and the virtues of its anonymous owner, and concludes in an inscription panel above the masab, containing the date of the woodwork.\^/

apartment of the sultan's mother in Topkapi palace

“Although most of the woodwork elements date to the early eighteenth century, some elements reflect changes over time in its original historical context, as well as adaptations to its museum setting. The most dramatic change has been the darkening of the layers of varnish that were applied periodically while the room was in situ, which now obscure the brilliance of the original palette and the nuance of the decoration. It was customary for wealthy Damascene home-owners to refurbish important reception rooms periodically, and some parts of the room belong to restorations of the later 18th and early 19th centuries, reflecting the shifting tastes of Damascene interior decoration: for example, the cupboard doors on the south wall of the tazar bear architectural vignettes in the "Turkish Rococo" style, along with cornucopia motifs and large, heavily gilded calligraphic medallions.\^/

“Other elements in the room relate to the pastiche of its museum installation. The square marble panels with red and white geometric patterns on the tazar floor as well as the opus sectile riser of the step leading up to the seating area actually originate from another Damascus residence, and date to the late 18th or 19th century. On the other hand, the 'ataba fountain may pre-date the woodwork, and the whether it came from the same reception room as the woodwork is uncertain. The tile ensemble on the back of the masab niche was selected from the Museum collection and incorporated in the 1970s installation of the room. In 2008, the room was dismantled from its previous location near the entrance of the Islamic Art galleries, so that it could be re-installed in a zone within the suite of new galleries devoted to Ottoman art. De-installation presented an opportunity for in-depth study and conservation of its elements. The 1970s installation was known as the "Nur al-Din" room, because that name appeared in some of the documents related to its sale. Research indicates that "Nur al-Din" probably referred not to a former owner but to a building near the house that was named after the famous twelfth-century ruler, Nur al-Din Zengi or his tomb. This name has been replaced by "Damascus Room" – a title that better reflects the room's unspecified provenance.”\^/

Daily Life in Ottoman Turkey: Bread and Permits

Eva March Tappan wrote: “Natives who became Christians were put out of their guilds, and therefore it became almost impossible for them to find work. Many were reduced to poverty, even to beggary. Dr. Hamlin, the President of Robert College, discovered that when Mahomet II took Constantinople, in I453, the act of capitulation declared that every foreign nation located in that city might have the privilege of establishing a mill and bakery. "Americans have never claimed this right," said Dr. Hamlin, "and I can therefore claim it." The first step was to obtain the firman, or formal permit, from the Government. [Source: From: Eva March Tappan, ed., The World’s Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. VI: Russia, Austria-Hungary, The Balkan States, and Turkey, pp. 569-572]

Dr. Cyrus Hamlin wrote in “Turkish Bread” (1907): There was some curious experience connected with the firman, which so well illustrates "the way things go" in Constantinople, and in the East generally, that I will narrate it. The Government readily promised the firman; and, had no opposition occurred, would have given it. But one of the great pashas was a very extensive owner of mills and bakeries. The mills were all horse-mills then, and he evidently feared that the small steam-mill proposed would grow. He knew what usually comes of giving foreigners an entering wedge. He had the immense guild, also, whose interests were one with his. The promise of the firman was not performed. No Government on earth was ever so skillful in putting off a thing as the Turkish. At length, I began to build, on the faith of the promise. We had not proceeded far, before engineers from the Porte came to examine and take a plan of our works. I knew that foretold an interdict, and counseled all to shut the gate, if they saw an officer approaching. By treaty right, no one could thus enter without an officer accompanying him from our embassy; and I was sure they would not even apply for one, but hope to carry the point irregularly, and to arrest and imprison all the men found working.

“One day, at noon recess, the officer came, and Demetri, whom he wished first of all to arrest, was standing in the street, eating bread and olives. "Where is Demetri Calfa?" said he to Demetri himself. "I just saw him at the wine-shop," was the cool reply. "Turn round the corner to your right, at the foot of the street." The officer soon returned; the workmen were all in the attic, the students and I were below. "Who is the master-workman here?" "I am, sir." "I want the rayah master." "There is no such man here." "I arrest you all, young men, and make 'pydos' interdict." "Keep to work, boys! You are students, and can't be arrested in this way." "But these are workmen “"No, sir; they are all my students! “An unwary workman in the attic had, in the mean time, thrust out his head; and the officer saw him. "Ho! you skulker, you are a workman! Come down here, you will go with me!" "I am one of Mr. Hamlin's scholars!" was the cool reply. "You a scholar! Let me hear you read!" The man, who was a good carpenter and a great wag, and belonged to no particular faith, turned round, found a New Testament in Armeno-Turkish, and began to read appropriate passages. The officer was confounded. I then put my hand upon his shoulder, told him he was violating treaty rights, that he could reign on the other side of the wall, but I, within, until he should come in a legal manner; and so I led him out and shut the gate. He sat down upon a stone, and began to soliloquize. "Such an interdict never saw I! The master-workman is a foreign hodja; the workmen are all his students! I am breaking the treaty! My soul! what reply shall I carry back?" I went out and comforted him, and told him to say that if the Porte should violate the treaty again, I should accuse it to the embassy and the American Government. And, as the right was included in the ACapitulations,@ I should inform other embassies of the act. It can enter this establishment again only through our embassy.

Bedouins making bread

“The Turkish Government had placed itself in a false position. It must now apply to the embassy and ignore its oft-repeated promise; or it must give the firman. It wisely chose the latter; and the interdict became the amusement of the village, and the chagrin of the pasha and bakers who had instigated it. A very slight matter secured a large patronage to the bakery. Our bread was made a little over weight, instead of following the example of the bakers, who always make it a little under weight. As often as the examiners tried our bread, they said "Mashallah!" and passed on.

“The people soon learned the fact; and the amount of time that they would spend to obtain this bread would exceed in value fourfold the difference of weight they would thus gain. The truth is, all men like to be treated well in a bargain, and do not so much mind the amount. We had introduced another improvement. Attempts had been made to bring into market yeast bread, but had failed. The bread of the country is universally leavened bread; and no one but foreigners knew anything about making bread with hop yeast. Having first mastered the art of making good hop yeast, the bread we produced became known as "Protestant bread" and commanded a good sale at an advanced price.”

Smallpox Vaccination in Turkey in 1717

Paul Halsall of Fordham University wrote: In 1717, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689-1762) arrived with her husband, the British ambassador, at the court of the Ottoman Empire. She wrote voluminously of her travels. In this selection she noted that the local practice of deliberately stimulating a mild form of the disease through innoculation conferred immunity. She had the procedure performed on both her children. By the end of the eighteenth century, the English physician Edward Jenner was able to cultivate a serum in cattle, which, when used in human vaccination, eventually led to the worldwide eradication of the illness. [Source: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook, sourcebooks.fordham.edu]

In her description of a smallpox vaccination in Turkey, Lady Montagu wrote: “A propos of distempers, I am going to tell you a thing, that will make you wish yourself here. The small-pox, so fatal, and so general amongst us, is here entirely harmless, by the invention of engrafting, which is the term they give it. There is a set of old women, who make it their business to perform the operation, every autumn, in the month of September, when the great heat is abated. People send to one another to know if any of their family has a mind to have the small-pox; they make parties for this purpose, and when they are met (commonly fifteen or sixteen together) the old woman comes with a nut-shell full of the matter of the best sort of small-pox, and asks what vein you please to have opened. [Source: Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Letters of the Right Honourable Lady My Wy Me: Written During her Travels in Europe, Asia and Africa. . . , vol. 1 (Aix: Anthony Henricy, 1796), pp. 167-69; letter 36, to Mrs. S. C. from Adrianople, n.d.]

small pox vaccination in Palestine in 1921

“She immediately rips open that you offer to her, with a large needle (which gives you no more pain than a common scratch) and puts into the vein as much matter as can lie upon the head of her needle , and after that, binds up the little wound with a hollow bit of shell, and in this manner opens four or five veins. The Grecians have commonly the superstition of opening one in the middle of the forehead, one in each arm, and one on the breast, to mark the sign of the Cross; but this has a very ill effect, all these wounds leaving little scars, and is not done by those that are not superstitious, who chuse to have them in the legs, or that part of the arm that is concealed. The children or young patients play together all the rest of the day, and are in perfect health to the eighth. Then the fever begins to seize them, and they keep their beds two days, very seldom three. They have very rarely above twenty or thirty in their faces, which never mark, and in eight days time they are as well as before their illness. Where they are wounded, there remains running sores during the distemper, which I don't doubt is a great relief to it.

“Every year, thousands undergo this operation, and the French Ambassador says pleasantly, that they take the small-pox here by way of diversion, as they take the waters in other countries. There is no example of any one that has died in it, and you may believe I am well satisfied of the safety of this experiment, since I intend to try it on my dear little son. I am patriot enough to take the pains to bring this useful invention into fashion in England, and I should not fail to write to some of our doctors very particularly about it, if I knew any one of them that I thought had virtue enough to destroy such a considerable branch of their revenue, for the good of mankind. But that distemper is too beneficial to them, not to expose to all their resentment, the hardy wight that should undertake to put an end to it. Perhaps if I live to return, I may, however, have courage to war with them. Upon this occasion, admire the heroism in the heart of Your friend, etc. etc.”

Whirling Dervishes Hall in 1902

Julia Pardoe wrote in “The Dancing Dervishes” (1902):“The tekie [convent] is a handsome building with projecting wings, in which the community live very comfortably with their wives and children; and whence, having performed their religious duties, they sally forth to their several avocations in the city, and mingle with their fellow men upon equal terms. The dervishes are forbidden to accumulate wealth in order to enrich either themselves or their convent. The most simple fare, the least costly garrnents, serve alike for their own use and for that of their families: industry, temperance, and devotion are their duties; and, as they are at liberty to secede from their self-imposed obligations whenever they see fit to do so, there is no lukewarmness among the community, who find time throughout the whole year to devote many hours to God, even of their most busy days; and, unlike their fellow citizens, the other Mussulmans, they throw open the doors of their chapel to strangers, only stipulating that gentlemen shall put off their shoes ere they enter. [Source: From: Eva March Tappan, ed., The World’s Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. VI: Russia, Austria-Hungary, The Balkan States, and Turkey, pp. 573-578]

Mevlevi (whirling dervishes) in 1887

“This chapel, which has been erroneously called a "mosque," is an octagon building of moderate size, neatly painted in fresco. The center of the floor is railed off, and the inclosure is sacred to the brotherhood; while the outer circle, covered with Indian matting, is appropriated to visitors. A deep gallery runs round six sides of the building, and beneath it, on your left hand as you enter, you remark the lattices through which the Turkish women witness the service. A narrow mat surrounds the circle within the railing, and upon this the brethren kneel during the prayers; while the center of the floor is so highly polished by the perpetual friction that it resembles a mirror, and the boards are united by nails with heads as large as a shilling, to prevent accidents to the feet of the dervishes during their evolutions. A bar of iron descends from the center of the domed roof, to which transverse bars are attached, bearing a vast number of glass lamps of different colors and size; and against many of the pillars, of which I counted four-and-twenty, supporting the dome, are hung frames, within which are inscribed passages from the Prophets.

“Above the seat of the superior, the name of the founder of the tekie is written in gold on a black ground, in immense characters. This seat consists of a small carpet, above which is spread a crimson rug; and on this the worthy principal was squatted when we entered, in an ample cloak of Spanish brown, with large hanging sleeves, and his geulaf, or high hat of gray felt, encircled with a green shawl. I pitied him that his back was turned towards the glorious Bosphorus, that was distinctly seen through the four large windows at the extremity of the chapel, flashing in the light, with the slender minarets and lordly mosques of Stamboul gleaming out in the distance.

Whirling Dervishes in 1902

Julia Pardoe wrote in “The Dancing Dervishes” (1902): “One by one, the dervishes entered the chapel, bowing profoundly at the little gate of the inclosure, took their places on the mat, and, bending down, reverently kissed the ground; and then, folding their arms meekly on their breasts, remained buried in prayer, with their eyes closed and their bodies swinging slowly to and fro. They were all enveloped in wide cloaks of dark-colored cloth with pendent sleeves; and wore their geulafs, which they retained during the whole of the service. The service commenced with an extemporaneous prayer from the chief priest, to which the attendant dervishes listened with arms folded upon their breasts and their eyes fixed on the ground. [Source: From: Eva March Tappan, ed., The World’s Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. VI: Russia, Austria-Hungary, The Balkan States, and Turkey, pp. 573-578]

“At its conclusion, all bowed their foreheads to the earth; and the orchestra struck into one of those peculiarly wild and melancholy Turkish airs which are unlike any other music that I ever heard. Instantly, the full voices of the brethren joined in chorus, and the effect was thrilling; now the sounds died away like the exhausted breath of a departing spirit, and suddenly they swelled once more into a deep and powerful diapason that seemed scarce earthly. A second stillness of about a minute succeeded, when the low, solemn music was resumed, and the dervishes, slowly rising from the earth, followed their superior three times round the inclosure; bowing down twice under the shadow of the name of their founder, suspended above the seat of the high priest.

“This reverence was performed without removing their folded arms from their breasts—the first time on the side by which they approached, and afterwards on that opposite, which they gained by slowly revolving on the right foot, in such a manner as to prevent their turning their backs towards the inscription. The procession was closed by a second prostration, after which, each dervish, having gained his place, cast off his cloak, and such as had walked in woolen slippers withdrew them, and, passing solemnly before the chief priest, they commenced their evolutions. The extraordinary ceremony which gives its name to the dancing, or, as they are really and much more appropriately called, the turning dervishes,—for nothing can be more utterly unlike dancing than their evolutions,—is not without its meaning.”

Prayers and Rituals During a Whirling Dervish Event in 1902

Julia Pardoe wrote in “The Dancing Dervishes” (1902): “The community first pray for pardon of their past sins, and the amendment of their future lives; and then, after a silent supplication for strength to work out the change, they figure, by their peculiar and fatiguing movements, their anxiety to "shake the dust from their feet," and to cast from them all worldly ties. [Source: From: Eva March Tappan, ed., The World’s Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. VI: Russia, Austria-Hungary, The Balkan States, and Turkey, pp. 573-578]

“Immediately after passing with a solemn reverence, twice performed, the place of the high priest, who remained standing, the dervishes spread their arms and commenced their revolving motion; the palm of the right hand being held upwards, and that of the left turned down. Their under-dresses (for, as I before remarked, they had laid aside their cloaks) consisted of a jacket and petticoat of dark-colored cloth, that descended to their feet; the higher order of brethren being clad in green, and the others in brown, or a sort of yellowish gray; about their waists they wore wide girdles, edged with red, to which the right side of the jacket was closely fastened, while the left hung loose: their petticoats were of immense width, and lay in large plaits beneath the girdles, and, as the wearers swung round, formed a bell-like appearance; these latter garments, however, are only worn during the ceremony, and are exchanged in summer for white ones of lighter material. The number of those who were "on duty," for I know not how else to express it, was nine; seven of them being men, and the remaining two, mere boys, the youngest certainly not more than ten years of age.

“Nine, eleven, and thirteen are the mystic numbers, which, however great the strength of the community, are never exceeded; and the remaining members of the brotherhood, during the evolutions of their companions, continue engaged in prayer within the inclosure. These on this occasion amounted to about a score, and remained each leaning against a pillar: while the beat of the drum in the gallery marked the time to which the revolving dervishes moved, and the effect was singular to a degree that baffles description. So true and unerring were their motions, that, although the space which they occupied was somewhat circumscribed, they never once gained upon each other: and for five minutes they continued twirling round and round, as though impelled by machinery, their pale, passionless countenances perfectly immobile, their heads slightly declined towards the right shoulder, and their inflated garments creating a cold, sharp air in the chapel, from the rapidity of their action. At the termination of that period, the name of the Prophet occurred in the chant, which had been unintermitted in the gallery; and, as they simultaneously paused, and, folding their hands upon their breasts, bent down in reverence at the sound, their ample garments wound about them at the sudden check, and gave them, for a moment, the appearance of mummies.

“An interval of prayer followed; and the same ceremony was performed three times; at the termination of which they all fell prostrate on the earth, when those who had hitherto remained spectators flung their cloaks over them, and the one who knelt on the left of the chief priest rose, and delivered a long prayer, divided into sections, with a rapid and solemn voice, prolonging the last word of each sentence by the utterance of "Ha—ha—ha"—with a rich depth of octave that would not have disgraced Phillips.

“This prayer was for "the great ones of the earth"—the magnates of the land—all who were "in authority over them"; and at each proud name they bowed their heads upon their breasts, until that of the sultan was mentioned, when they once more fell flat upon the ground, to the sound of the most awful howl I ever heard.

“This outburst from the gallery terminated the labors of the orchestra, and the superior, rising to his knees, while the others continued prostrate, in his turn prayed for a few instants; and then, taking his stand upon the crimson rug, they approached him one by one, and, clasping his hand, pressed it to their lips and forehead. When the first had passed, he stationed himself on the right of the superior, and awaited the arrival of the second, who, on reaching him, bestowed on him also the kiss of peace, which he had just proffered to the chief priest; and each in succession performed the same ceremony to all those who had preceded him, which was acknowledged by gently stroking down the beard. This was the final act of the exhibition; and, the superior having slowly and silently traversed the inclosure, in five seconds the chapel was empty, and the congregation busied at the portal in reclaiming their boots, shoes, and slippers.

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History “ by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples “ by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures “ edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994); “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, BBC, Al Jazeera, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018