OTTOMAN PROVINCES

Ottomans controlled the Kaaba, Islam's holiest site, in Mecca

Beginning in the 16th century, much of the Arabic-speaking regions of North Africa and the Middle East became Ottoman provinces. There were few economic, political or intellectual achievements associated with the Arabs that occurred in this period.

In 1516-17, the Ottomans defeated the Mamluks and absorbed Syria, Egypt and western Arabia into their empire. The provinces of Aleppo, Damascus and Tripoli were so valuable and brought in so much tax revenue they were controlled directly by Istanbul. Aleppo was a major international trading center . Damascus was the kick off point for caravans to Mecca. Control was maintained by striking deals with powerful families in Syria.

The Ottoman Empire organized society around the concept of the millet, or autonomous religious community. The non-Muslim "People of the Book" (Christians and Jews) owed taxes to the government; in return they were permitted to govern themselves according to their own religious law in matters that did not concern Muslims. The religious communities were thus able to preserve a large measure of identity and autonomy. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, Library of Congress, 1988 *]

The administrative system in a Turkish vilayet (province) was under a wali (governor general) appointed by the sultan. Province were composed of sanjaks (subprovinces), each administered by a mutasarrif (lieutenant governor) responsible to the governor general. These subprovinces were each divided into districts. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Libya: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1987*]

Executive officers from the governor general downward were Turks. The mutasarrif was in some cases assisted by an advisory council and, at the lower levels, Turkish officials relied on aid and counsel from the tribal shaykhs. Administrative districts below the subprovincial level corresponded to the tribal areas that remained the focus of the Arabs' identification.*

Although the system was logical and appeared efficient on paper, it was never consistently applied. In an effort to provide a tax base in North Africa, the Turks attempted unsuccessfully to stimulate agriculture. However, in general, nineteenth-century Ottoman rule was characterized by corruption, revolt, and repression. The region was a backwater province in a decaying empire that had been dubbed the "sick man of Europe."

Websites and Resources: Ottoman Empire and Turks: The Ottomans.org theottomans.org ; Ottoman Text Archive Project – University of Washington courses.washington.edu ; Wikipedia article on the Ottoman Empire Wikipedia ; Encyclopædia Britannica article on the Ottoman Empire britannica.com ; American Travelers to the Holy Land in the 19th Century Shapell Manuscript Foundation shapell.org/historical-perspectives/exhibitions ; Ottoman Empire and Turk Resources – University of Michigan umich.edu/~turkis ; Turkey in Asia, 1920 wdl.org ; Wikipedia article on the Turkish People Wikipedia ; Turkish Studies, Turkic republics, regions, and peoples at University of Michigan umich.edu/~turkish/turkic ; Türkçestan Orientaal's links to Turkic languages users.telenet.be/orientaal/turkcestan ; Turkish Culture Portal turkishculture.org ; ATON, the Uysal-Walker Archive of Turkish Oral Narrative at Texas Tech University aton.ttu.edu ; The Horse, the Wheel and Language, How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes shaped the Modern World", David W Anthony, 2007 archive.org/details/horsewheelandlanguage ; Wikipedia article on Eurasian nomads Wikipedia

Pashas and Ottoman Rule Over Its Provinces

Nazin Pasha, governor of Aleppo

The Ottomans ruled their provinces through pashas, who governed with unlimited authority over the land under their control, although they were responsible ultimately to the Sublime Porte. Pashas were both administrative and military leaders. So long as they collected their taxes, maintained order, and ruled an area not of immediate military importance, the Sublime Porte left them alone. In turn the pashas ruled smaller administrative districts through either a subordinate Turk or a loyal Arab. Occasionally, as in the area that became Lebanon, the Arab subordinate maintained his position more through his own power than through loyalty. Throughout Ottoman rule, there was little contact with the authorities except among wealthier Syrians who entered government service or studied in Turkish universities. [Source: Thomas Collelo, ed. Syria: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1987 *]

The system was not particularly onerous because the Turks respected Arabic as the language of the Quran and accepted the mantle of defenders of the faith. Damascus was made the major entrepot for Mecca, and as such it acquired a holy character to Muslims because of the baraka (spiritual force or blessing) of the countless pilgrims who passed through on the hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca.*

Ottoman administration often followed patterns set by previous rulers. Each religious minority--Shia Muslim, Greek Orthodox, Maronite, Armenian, and Jewish--constituted a millet. The religious heads of each community administered all personal status law and performed certain civil functions as well.*

Syria Under Ottoman Rule

The Syrian economy did not flourish under the Ottomans. At times attempts were made to rebuild the country, but on the whole Syria remained poor. The population decreased by nearly 30 percent, and hundreds of villages virtually disappeared into the desert. At the end of the eighteenth century only one-eighth of the villages formerly on the register of the Aleppo pashalik (domain of a pasha) were still inhabited. Only the area now known as Lebanon achieved economic progress, largely resulting from the relatively independent rule of the Druze amirs.*

Although impoverished by Ottoman rule, Syria continued to attract European traders, who for centuries had transported spices, fruits, and textiles from the Middle East to the West. By the fifteenth century Aleppo was the Middle East's chief marketplace and had eclipsed Damascus in wealth, creating a rivalry between the two cities that continues.*

With the traders from the West came missionaries, teachers, scientists, and tourists whose governments began to clamor for certain rights. France demanded the right to protect Christians, and in 1535 Sultan Sulayman I granted France several "capitulations" — extraterritorial rights that developed later into political semiautonomy, not only for the French, but also for the Christians protected by them. The British acquired similar rights in 1580 and established the Levant Company in Aleppo. By the end of the eighteenth century, the Russians had claimed protective rights over the Greek Orthodox community.*

Damascus Under Ottoman Rule

On Damascus in the 18th century under century of Ottoman rule, Ellen Kenney of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “With a population of 80-90,000, it served as the provincial capital of the administrative region of southern Syria, which included parts of present-day Israel, Palestine, Jordan. While Istanbul exerted military and administrative control in the city, its social and cultural presence was more nuanced. For centuries, Damascus had functioned as an international nexus to which people traveled to study in its famous madrasas and worship in its renowned sanctuaries. [Source: Ellen Kenney, Department of Islamic Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Kenney, Ellen. "The Damascus Room", Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2011, metmuseum.org \^/]

“The city also served as one of the main gathering places for the Hajj caravans to Mecca, with an estimated 20,000 pilgrims congregating there annually. It was one of the most prosperous commercial centers in the empire, supported mainly by local agriculture and its role as a regional market-place. In keeping with the globalizing trend of the times, wealthy Damascenes interested in the latest fashions looked not just to Istanbul, but beyond: they adopted select European styles and collected imports from both Europe and East Asia. Thus, eighteenth-century Damascus reflected cosmopolitan zeitgeist against a backdrop firmly-rooted in tradition.

“Within the city walls, Ottoman Damascus was densely built-up. Palatial residences stood alongside more humble dwellings, bath-houses, mausoleums, schools and places of worship, all within a grid of bustling market streets, narrow alleys and cul-de-sacs. Usually the external facades of these buildings were contiguous with those adjacent to them. In Damascus, constructions consisted of a first story of masonry surmounted by upper stories of timber and sun-baked brick coated with plaster and white-wash, unlike many other towns in the region where the primary construction material was stone. From the street, even the most elegant of residences in Ottoman-period Damascus looked unassuming.\^/

Ottoman Period in Iraq (1534-1918)

Copper Bazaar in Baghdad

Beginning in the early sixteenth century, the Sunni Turkish Ottoman Empire struggled against the Shia Persian Safavi Empire for control of Iraq. The Ottoman Empire controlled Iraq for most of the ensuing four centuries. However, the Safavis made substantial inroads, and Iraq was under the de facto authority of tribal confederations beginning in the seventeenth century. This trend was reversed in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries as the Mamluks took control of most of modern-day Iraq. After Mamluk rule ended in 1831, the “tanzimat “administrative and educational reforms of the Ottoman ruler Midhat Pasha increased the influence of urban culture in Iraq. In the same period, Western Europe established commercial outposts and brought technological advances to Iraq. Beginning in 1908, the influence of the pro-Western Young Turk faction in the Ottoman government introduced democratic concepts while alienating Arab parts of the empire by a campaign to centralize and “Turkify” Ottoman holdings. [Source: Library of Congress, August 2006 **]

By the early twentieth century, the decrepit Ottoman Empire was an area of conflict among the European powers. In World War I, British and Ottoman forces fought on Iraqi territory. After leading a revolt by Arab tribes in Iraq, Transjordan, and Syria, in 1917 the British occupied most of modern-day Iraq. Disappointing Arab ambitions for independence after the war, the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 made Iraq a British territory under a League of Nations mandate. The postwar British government faced nationalist sentiment that evolved into terrorist activity by secret societies. The Great Iraqi Revolution of 1920 united Shias and Sunnis and brought about an Arab provisional government headed by King Faisal, son of a Saudi royal line. Faisal never established legitimacy or stability in Iraq because he was not an Iraqi by birth; he remained under British control, and his government was predominantly Sunni.

Mamluks Then Ottomans Take Over Iraq

The cycle of tribal warfare and of deteriorating urban life that began in the thirteenth century with the Mongol invasions was temporarily reversed with the reemergence of the Mamluks. In the early eighteenth century, the Mamluks began asserting authority apart from the Ottomans. Extending their rule first over Basra, the Mamluks eventually controlled the Tigris and Euphrates river valleys from the Persian Gulf to the foothills of Kurdistan. For the most part, the Mamluks were able administrators, and their rule was marked by political stability and by economic revival. The greatest of the Mamluk leaders, Suleyman the II (1780-1802), made great strides in imposing the rule of law. The last Mamluk leader, Daud (1816-31), initiated important modernization programs that included clearing canals, establishing industries, training a 20,000-man army, and starting a printing press. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, Library of Congress, 1988 *]

Mamluk

The Mamluk period ended in 1831, when a severe flood and plague devastated Baghdad, enabling the Ottoman sultan, Mahmud II, to reassert Ottoman sovereignty over Iraq. Ottoman rule was unstable; Baghdad, for example, had more than ten governors between 1831 and 1869. In 1869, however, the Ottomans regained authority when the reform-minded Midhat Pasha was appointed governor of Baghdad. Midhat immediately set out to modernize Iraq on the Western model. The primary objectives of Midhat's reforms, called the tanzimat, were to reorganize the army, to create codes of criminal and commercial law, to secularize the school system, and to improve provincial administration. He created provincial representative assemblies to assist the governor, and he set up elected municipal councils in the major cities. Staffed largely by Iraqi notables with no strong ties to the masses, the new offices nonetheless helped a group of Iraqis gain administrative experience.

Ottoman Rule in Iraq

By establishing government agencies in the cities and by attempting to settle the tribes, Midhat altered the tribal-urban balance of power, which since the thirteenth century had been largely in favor of the tribes. The most important element of Midhat's plan to extend Ottoman authority into the countryside was the 1858 TAPU land law (named after the initials of the government office issuing it). The new land reform replaced the feudal system of land holdings and tax farms with legally sanctioned property rights. It was designed both to induce tribal shaykhs to settle and to give them a stake in the existing political order. In practice, the TAPU laws enabled the tribal shaykhs to become large landowners; tribesmen, fearing that the new law was an attempt to collect taxes more effectively or to impose conscription, registered community-owned tribal lands in their shaykhs' names or sold them outright to urban speculators. As a result, tribal shaykhs gradually were transformed into profit-seeking landlords while their tribesmen were relegated to the role of impoverished sharecroppers. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, Library of Congress, 1988 *]

Midhat also attempted to replace Iraq's clerically run Islamic school system with a more secular educational system. The new, secular schools provided a channel of upward social mobility to children of all classes, and they led slowly to the growth of an Iraqi intelligentsia. They also introduced students for the first time to Western languages and disciplines.

The introduction of Western disciplines in the schools accompanied a greater Western political and economic presence in Iraq. The British had established a consulate at Baghdad in 1802, and a French consulate followed shortly thereafter. European interest in modernizing Iraq to facilitate Western commercial interests coincided with the Ottoman reforms. Steamboats appeared on the rivers in 1836, the telegraph was introduced in 1861, and the Suez Canal was opened in 1869, providing Iraq with greater access to European markets. The landowning tribal shaykhs began to export cash crops to the capitalist markets of the West.

Egyptian Influence in Arabia

In the Egyptians' attempt to establish control over the peninsula, Muhammad Ali removed members of the Al Saud from the area. Following orders from the Ottoman sultan, he sent Abd Allah to Istanbul — where he was publicly beheaded — and forced other members of the family to leave the country. A few prominent members of the Al Saud found their way to Egypt. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Saudi Arabia: A Country Study, U.S. Library of Congress, 1992 *]

Al Masjid al-Nabawi in Saudi Arabia

The Egyptians turned next to the material monument of the Al Saud rule, the city of Ad Diriyah. They razed its walls and buildings and destroyed its palm groves so that the area could not support any agricultural settlement for some time. The Egyptians then sent troops to strategic parts of the peninsula to tighten their grip on it. They garrisoned Al Qatif, a port on the Persian Gulf that supplied some of the important centers in eastern Arabia and maintained various forces along the Red Sea coast in the west.*

In the Hijaz, Muhammad Ali restored the authority of the Sharifs, who had ruled the area from Mecca since the tenth century. However, Turki ibn Abd Allah, the uncle of the next-to- last ruler (Saud), upset Egyptian efforts to exercise authority in the area. Turki had fought at Ad Diriyah, but managed to escape the Egyptians when the town fell in 1818. He hid for two years among loyal forces to the south, and after a few unsuccessful attempts, recaptured Ad Diriyah in 1821. From the ruins of Ad Diriyah, Turki proceeded to Riyadh, another Najdi city. This eventually became the new Al Saud base. Forces under Turki's control reclaimed the rest of Najd in 1824.*

Turki's relatively swift retaking of Najd showed the extent to which the Al Saud-Wahhabi authority had been established in the area over the previous fifty years. The successes of the Wahhabi forces had done much to promote tribal loyalty to the Al Saud. But the Wahhabi principles of the Al Saud rule were equally compelling. After Muhammad ibn al Wahhab's death in 1792, the leader of Al Saud assumed the title of imam. Thus, Al Saud leaders were recognized not just as shaykhs or leaders, but as Wahhabi imams, political and religious figures whose rule had an element of religious authority.*

Turki and his successors ruled from Riyadh over a wide area. They controlled the region to the north and south of Najd and exerted considerable influence along the western coast of the Persian Gulf. This was no state but a large sphere of influence that the Al Saud held together with a combination of treaties and delegated authority. In the Shammar Mountains to the north, for instance, the Al Saud supported the rule of Abd Allah ibn Rashid with whom Turki maintained a close alliance. Later, Turki's son Faisal cemented this alliance by marrying his son, Talal, to Abd Allah's daughter, Nurah. Although this family-to-family connection worked well, the Al Saud preferred to rely in the east on appointed leaders to rule on their behalf. In other areas, they were content to establish treaties under the terms of which tribes agreed to defend the family's interests or to refrain from attacking the Al Saud when the opportunity arose.*

Saudi Rule within the Egyptian Sphere of Influence

Within their sphere of influence, the Al Saud could levy troops for military campaigns from the towns and tribes under their control. Although these campaigns were mostly police actions against recalcitrant tribes, the rulers described them as holy wars (jihad), which they conducted according to religious principles. The tribute that the Al Saud demanded from those under their control was also based on Islamic principles. Towns, for instance, paid taxes at a rate established by Muslim law, and the troops that accompanied the Al Saud on raiding expeditions returned one-fifth of their booty to the Al Saud treasury according to sharia (Muslim Law) requirements. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Saudi Arabia: A Country Study, U.S. Library of Congress, 1992 *]

Al Saud Abdulrahman al-Faisal in 1875

The collection of tribute was another indication of the extensive influence the Al Saud derived because of their Wahhabi connections. Wahhabi religious ideas had spread through the central part of the Arabian Peninsula; as a result, the Al Saud influenced decisions even in areas not under their control, such as succession battles and questions of tribute. Their influence in the Hijaz, however, remained restricted. Not only were the Egyptians and Ottomans careful that the region not slip away again, but Wahhabi ideas had not found a receptive audience in western Arabia. Accordingly, the family was unable to gain a foothold in the Hijaz during the nineteenth century.*

The Al Saud maintained authority in Arabia by controlling several factors. First, they could resist, or at least accommodate, Egyptian interference. After 1824 when the Egyptians could no longer maintain outright military control over Arabia, they turned to political intrigues. Turki, for instance, was assassinated in 1834 by a member of the Al Saud who had recently returned from Cairo. When Turki's son, Faisal, succeeded his father, the Egyptians supported a rival member of the family, Khalid ibn Saud, and with Egyptian assistance Khalid controlled Najd for the next four years.*

Muhammad Ali and the Egyptians were severely weakened after the British and French defeated their fleet off the coast of Greece in 1827. This prevented the Egyptians from exerting much influence in Arabia, but it left the Al Saud with the problem of the Ottomans, whose ultimate authority Turki eventually acknowledged. The challenge to the sultan had helped end the first Al Saud empire in 1818, so later rulers chose to accommodate the Ottomans as much as they could. The Al Saud eventually became of considerable financial importance to the Ottomans because they collected tribute from the rich trading state of Oman and forwarded much of this to the Sharifs in Mecca, who relayed it to the sultan. In return the Ottomans recognized the Al Saud authority and left them alone for the most part.*

Ottoman Influence in Arabia

The Ottomans, however, sometimes tried to expand their influence by supporting renegade members of the Al Saud. When Faisal's two sons, Abd Allah and Saud, vied to take over the empire from their father, Abd Allah enlisted the aid of the Ottoman governor in Iraq, who used the opportunity to take Al Qatif and Al Hufuf in eastern Arabia. The Ottomans were eventually driven out, but until the time of Abd al Aziz they continued to look for a relationship with the Al Saud that they could exploit. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Saudi Arabia: A Country Study, U.S. Library of Congress, 1992 *]

One of the reasons the Ottomans were unsuccessful was the growing British interest in Arabia. The British government in India considered the Persian Gulf to be its western flank and so became increasingly involved with the piracy of the Arab tribes on the eastern coast. The British were also anxious about potentially hostile Ottoman influence in an area so close to India and the Suez Canal. As a result, the British came into increasing contact with the Al Saud. As Wahhabi leaders, the Al Saud could exert some control over the tribes on the gulf coast, and they were simultaneously involved with the Ottomans. During this period, the Al Saud leaders began to play off the Ottomans and British against each other.*

Whereas the Al Saud were largely successful in handling the two great powers in the Persian Gulf, they did not do so well in managing their family affairs. The killing of Turki in 1834 touched off a long period of fighting. Turki's son, Faisal, held power until he was expelled from Riyadh by Khalid and his Egyptian supporters. Then, Abd Allah ibn Thunayan (from yet another branch of the Al Saud) seized Riyadh. He could maintain power only briefly, however, because Faisal, who had been taken to Cairo and then escaped, retook the city in 1845.*

Faisal ruled until 1865, lending some stability to Arabia. Upon his death, however, fighting started again, and his three sons, Abd Allah, Abd ar Rahman, and Saud — as well as some of Saud's sons — each held Riyadh on separate occasions. The political structure of Arabia was such that each leader had to win the support of various tribes and towns to conduct a campaign. In this way, alliances were constantly formed and reformed, and the more often this occurred, the more unstable the situation became.*

This instability accelerated the decline of the Al Saud after the death of Faisal. While the Al Saud was bickering, however, the family of Muhammad ibn Rashid, who controlled the area around the Shammar Mountains, had been gaining strength and expanding its influence in northern Najd. In 1890 Muhammad ibn Rashid, the grandson of the leader with whom Turki had first made an alliance, was in a position to enhance his own power. He removed the sons of Saud ibn Faisal from Riyadh and returned it to the nominal control of their uncle, Abd ar Rahman. Muhammad put effective control of the city, however, into the hands of his own garrison commander, Salim ibn Subhan. When Abd ar Rahman attempted to exert real authority, he was driven out of Riyadh. Thus, the Al Saud, along with the young Abd al Aziz, were obliged to take refuge with the amir of Kuwait.*

Mecca in 1897

Saudi’s Create a Kingdom Around Mecca

Abdul Aziz captured Riyadh in 1773 and claimed all of Nejd (central Arabia). His son Saud ibn Abdul Aziz caputed Mecca in 1803. By 1806, he controlled an empire that embraced Nejd, Hejaz (a province in western Arabia that embraces Mecca and Medina) and al-Hasa oasis and most of present-day Saudi Arabia. This empire is sometimes called the First Saudi Empire.

The Ottomans were not pleased by this development. In 1812, an Ottoman force, under the Viceroy of Egypt, Muhammad Ali, was dispatched to the Arabian Red Sea coast. After a long struggle, the Saudi forces were driven out of Hejaz and back to Diraiyah, which fell to the Ottomans in 1818. Saud’s son was captured and taken to Istanbul and beheaded.

Following a six-year period of Egyptian interference, the Al Saud regained political control of the Najd region in 1824 under Turki ibn Abd Allah, who rebuilt Riyadh and established it as the new center of Al Saud power. Although they did not control a centralized state, the Al Saud successfully controlled military resources, collected tribute, and resisted Egyptian attempts to regain a foothold in the region. From 1830 to 1891, the Al Saud maintained power and protected Arabia’s autonomy by playing the British and Ottomans against each other. External threats were largely kept at bay, but internal strife plagued the Al Saud throughout much of the century. After the assassination of Turki in 1834, the family devolved into a series of competing factions. The infighting and constant civil war ultimately led to the decline of the Al Saud and the rise of the rival Al Rashid family; the Al Saud were driven out of Riyadh and forced to take refuge in Kuwait. [Source: Library of Congress, September 2006 **]

The fortunes of the House of Saud were revived when its leaders rose up and captured most of Hejd and Hasa by 1865. This is known as the second Saudi Empire. It was broken up by internal conflicts. In 1891, the Al-Sauds were driven out Nejd by the Rashids. They first sought refuge on edge of the Empty Quarter and were ultimately provided with a safe haven by the ruling sheik of Kuwait.

The modern history of Arabia is often broken into three periods that follow the fortunes of the Al Saud. The first begins with the alliance between Muhammad ibn Saud and Muhammad ibn Abd al Wahhab and ends with the capture of Abd Allah. The second period extends from this point to the rise of the second Abd al Aziz ibn Saud, the founder of the modern state; the third consists of the establishment and present history of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.* [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Saudi Arabia: A Country Study, U.S. Library of Congress, 1992 *]

Ottoman Regency and Piracy in North Africa

western depiction of Barbarossa

Throughout the sixteenth century, Hapsburg Spain and the Ottoman Turks were pitted in a struggle for supremacy in the Mediterranean. Spanish forces had already occupied a number of other North African ports when in 1510 they captured Tripoli, destroyed the city, and constructed a fortified naval base from the rubble. Tripoli was of only marginal importance to Spain, however, and in 1524 the king-emperor Charles V entrusted its defense to the Knights of St. John of Malta. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Libya: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1987*]

Piracy, which for both Christians and Muslims was a dimension of the conflict between the opposing powers, lured adventurers from around the Mediterranean to the Maghribi coastal towns and islands. Among them was Khair ad Din, called Barbarossa, who in 1510 seized Algiers on the pretext of defending it from the Spaniards. Barbarossa subsequently recognized the suzerainty of the Ottoman sultan over the territory that he controlled and was in turn appointed the sultan's regent in the Maghrib. Using Algiers as their base, Barbarossa and his successors consolidated Ottoman authority in the central Maghrib, extended it to Tunisia and Tripolitania, and threatened Morocco.

In 1551 the knights were driven out of Tripoli by the Turkish admiral, Sinan Pasha. In the next year Draughut Pasha, a Turkish pirate captain named governor by the sultan, restored order in the coastal towns and undertook the pacification of the Arab nomads in Tripolitania, although he admitted the difficulty of subduing a people "who carry their cities with them." Only in the 1580s did the rulers of Fezzan give their allegiance to the sultan, but the Turks refrained from trying to exercise any influence there. Ottoman authority was also absent in Cyrenaica, although a bey (commander) was stationed at Benghazi late in the next century to act as agent of the government in Tripoli.*

Ottoman Take Over of North Africa

At about the time Spain was establishing its presidios in the Maghrib, the Muslim privateer brothers Aruj and Khair ad Din — the latter known to Europeans as Barbarossa, or Red Beard — were operating successfully off Tunisia under the Hafsids. In 1516 Aruj moved his base of operations to Algiers, but was killed in 1518 during his invasion of Tlemcen. Khair ad Din succeeded him as military commander of Algiers. The Ottoman sultan gave him the title of beylerbey (provincial governor) and a contingent of some 2,000 janissaries, well-armed Ottoman soldiers. With the aid of this force, Khair ad Din subdued the coastal region between Constantine and Oran (although the city of Oran remained in Spanish hands until 1791). Under Khair ad Din's regency, Algiers became the center of Ottoman authority in the Maghrib, from which Tunis, Tripoli, and Tlemcen would be overcome and Morocco's independence would be threatened. [Source: Helen Chapan Metz, ed. Algeria: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1994 *]

So successful was Khair ad Din at Algiers that he was recalled to Constantinople in 1533 by the sultan, Süleyman I (r. 1520-66), known in Europe as Süleyman the Magnificent, and appointed admiral of the Ottoman fleet. The next year he mounted a successful seaborne assault on Tunis. The next beylerbey was Khair ad Din's son Hassan, who assumed the position in 1544. Until 1587 the area was governed by officers who served terms with no fixed limits. Subsequently, with the institution of a regular Ottoman administration, governors with the title of pasha ruled for three-year terms. Turkish was the official language, and Arabs and Berbers were excluded from government posts.*

The pasha was assisted by janissaries, known in Algeria as the ojaq and led by an agha. Recruited from Anatolian peasants, they were committed to a lifetime of service. Although isolated from the rest of society and subject to their own laws and courts, they depended on the ruler and the taifa for income. In the seventeenth century, the force numbered about 15,000, but it was to shrink to only 3,700 by 1830. Discontent among the ojaq rose in the mid-1600s because they were not paid regularly, and they repeatedly revolted against the pasha. As a result, the agha charged the pasha with corruption and incompetence and seized power in 1659.*

Ottoman Rule in North Africa

The Ottoman Maghrib was formally divided into three regencies — at Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli. After 1565 authority as regent in Tripoli was vested in a pasha appointed by the sultan. The regency was provided a corps of janissaries, recruited from Turkish peasants who were committed to a lifetime of military service. The corps was organized into companies, each commanded by a junior officer with the rank of dey (literally, "maternal uncle"). It formed a self-governing military guild, subject to its own laws, whose interests were protected by the Divan, a council of senior officers that also advised the pasha. In time the pasha's role was reduced to that of ceremonial head of state and figurehead representative of Ottoman suzerainty, as real power came to rest with the army. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Libya: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1987*]

Barbarossa's fleet wintering in Toulon in 1543

The dey was in effect a constitutional autocrat, but his authority was restricted by the divan and the taifa, as well as by local political conditions. The dey was elected for a life term, but in the 159 years (1671-1830) that the system survived, fourteen of the twenty-nine deys were removed from office by assassination. Despite usurpation, military coups, and occasional mob rule, the day-to-day operation of government was remarkably orderly. In accordance with the millet system applied throughout the Ottoman Empire, each ethnic group — Turks, Arabs, Kabyles, Berbers, Jews, Europeans — was represented by a guild that exercised legal jurisdiction over its constituents.*

Mutinies and coups were frequent, and generally the janissaries were loyal to whoever paid and fed them most regularly. In 1611 the deys staged a successful coup, forcing the pasha to appoint their leader, Suleiman Safar, as head of government — in which capacity he and his successors continued to bear the title dey. At various times the dey was also pasha-regent. His succession to office occurred generally amid intrigue and violence. The regency that he governed was autonomous in internal affairs and, although dependent on the sultan for fresh recruits to the corps of janissaries, his government was left to pursue a virtually independent foreign policy as well.*

Tripoli, which had 30,000 inhabitants at the end of the seventeenth century, was the only city of any size in the regency. The bulk of its residents were Moors, as city-dwelling Arabs were known. Several hundred Turks and renegades formed a governing elite apart from the rest of the population. A larger component was the khouloughlis (literally, "sons of servants"), offspring of Turkish soldiers and Arab women who traditionally held high administrative posts and provided officers for the spahis, the provincial cavalry units that augmented the corps of janissaries. They identified themselves with local interests and were, in contrast to the Turks, respected by the Arabs. Regarded as a distinct caste, the khouloughlis lived in their menshia, a lush oasis located just outside the walls of the city. Jews and moriscos, descendants of Muslims expelled from Spain in the sixteenth century, were active as merchants and craftsmen, some of the moriscos also achieving notoriety as pirates. A small community of European traders clustered around the compounds of the foreign consuls, whose principal task was to sue for the release of captives brought to Tripoli by the corsairs. European slaves and larger numbers of enslaved blacks transported from the Sudan were a ubiquitous feature of the life of the city.*

Ottoman Administration in North Africa

The administrative system imposed by the Turks was typical of that found elsewhere in the Ottoman Empire. Tripolitania, as all three historic regions were collectively designated, became a Turkish vilayet (province) under a wali (governor general) appointed by the sultan. The province was composed of four sanjaks (subprovinces), each administered by a mutasarrif (lieutenant governor) responsible to the governor general. These subprovinces were each divided into about fifteen districts. [Source: Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Libya: A Country Study, Library of Congress, 1987*]

Executive officers from the governor general downward were Turks. The mutasarrif was in some cases assisted by an advisory council and, at the lower levels, Turkish officials relied on aid and counsel from the tribal shaykhs. Administrative districts below the subprovincial level corresponded to the tribal areas that remained the focus of the Arabs' identification.*

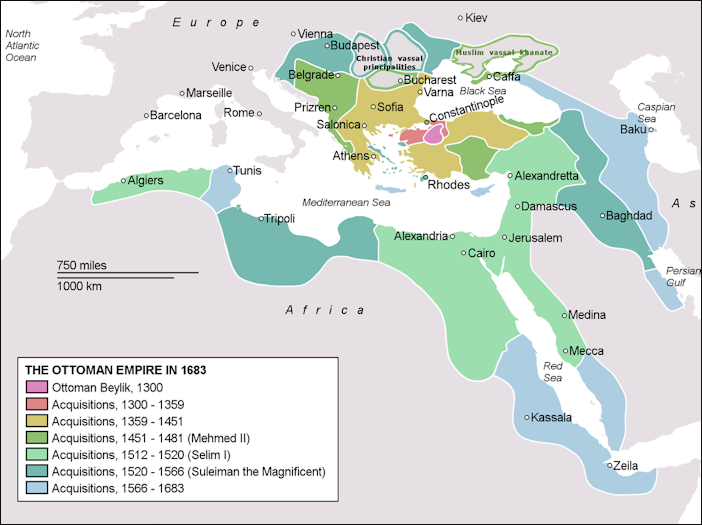

Ottoman Empire in 1683

Although the system was logical and appeared efficient on paper, it was never consistently applied throughout the country. The Turks encountered strong local opposition through the 1850s and showed little interest in implementing Ottoman control over Fezzan and the interior of Cyrenaica. In 1879 Cyrenaica was separated from Tripolitania, its mutasarrif reporting thereafter directly to Constantinople (present-day Istanbul). After the 1908 reform of the Ottoman government, both were entitled to send representatives to the Turkish parliament.*

In an effort to provide the country with a tax base, the Turks attempted unsuccessfully to stimulate agriculture. However, in general, nineteenth-century Ottoman rule was characterized by corruption, revolt, and repression. The region was a backwater province in a decaying empire that had been dubbed the "sick man of Europe."

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History “ by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples “ by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994); “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, BBC, Al Jazeera, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018