CULTURE AND ART IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE

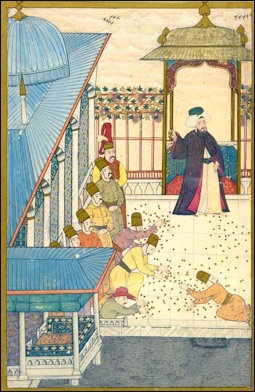

sultan throwing golden coins at Topkapi

Marika Sardar of New York University wrote: “The armature of the empire was instrumental in spreading the central Ottoman aesthetic to many new regions. On the level of imperial patronage, artistic production and design were carefully controlled by various official institutions. The Imperial Corps of Court Architects, founded in the 1520s, was responsible for preparing designs, procuring materials, and maintaining construction books for all buildings sponsored by the Ottoman family and their high officials. The nakkashane, or royal scriptorium, designed the patterns for carpets, tiles, metalwork, and textiles produced in imperial-funded workshops. Governors posted from Istanbul were also important in maintaining a certain level of stylistic homogeneity, as attested by architecture in the neighborhood around the Cairene port of Bulaq, developed under Ottoman patronage, and paintings from late sixteenth-century Baghdad, then under the governorship of Mehmed III’s chief artist Hasan. [Source:Marika Sardar Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

The Ottoman presence was in many ways limited to the major urban centers, however, and local culture was sustained among the different ethnic communities of the empire, such as the Christians of the Balkans and Armenia and the powerful Jewish and Greek merchants of Istanbul. In the provincial cities, coffeehouses and the homes of aristocratic families became the new centers of cultural exchange, replacing official institutions of learning and religion.

Local traditions in the arts continued to emerge even in official projects. Although the essential ground plan of the spacious, domed Ottoman mosque transferred from Istanbul, local interpretations of the plans sent from the capital affected the appearance of the facade or the proportions of the architectural elements. Eastern Mediterranean striped masonry appears at the Süleymaniye Mosque Complex in Damascus (1554–55) and barrel vaults, rather than semi-domes, surround the main dome of the Mosque of the Fisherman in Algiers (1660–61).

Websites and Resources: Ottoman Empire and Turks: The Ottomans.org theottomans.org ; Ottoman Text Archive Project – University of Washington courses.washington.edu ; Wikipedia article on the Ottoman Empire Wikipedia ; Encyclopædia Britannica article on the Ottoman Empire britannica.com ; American Travelers to the Holy Land in the 19th Century Shapell Manuscript Foundation shapell.org/historical-perspectives/exhibitions ; Ottoman Empire and Turk Resources – University of Michigan umich.edu/~turkis ; Turkey in Asia, 1920 wdl.org ; Wikipedia article on the Turkish People Wikipedia ; Turkish Studies, Turkic republics, regions, and peoples at University of Michigan umich.edu/~turkish/turkic ; Türkçestan Orientaal's links to Turkic languages users.telenet.be/orientaal/turkcestan ; Turkish Culture Portal turkishculture.org ; ATON, the Uysal-Walker Archive of Turkish Oral Narrative at Texas Tech University aton.ttu.edu ; The Horse, the Wheel and Language, How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes shaped the Modern World", David W Anthony, 2007 archive.org/details/horsewheelandlanguage ; Wikipedia article on Eurasian nomads Wikipedia

Websites and Resources: Islamic Art and Architecture: Islamic Arts & Architecture /web.archive.org ; British Museum britishmuseum.org Islamic Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org/toah/hd/orna ; Islamic Art Louvre Louvre ; Museum without Frontiers museumwnf.org ; Architecture of Islam ne.jp/asahi/arc ; Images of mosques all over the world, from the Aga Khan Documentation Center at MIT dome.mit.edu ; Islamic Images islamicacademy.org ; Victoria & Albert Museum vam.ac.uk ; Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, Qatar mia.org.qa ; CalligraphyIslamic, lots of Islamic calligraphy web.archive.org

Books: Çiçek, Kemal, ed. The Great Ottoman–Turkish Civilisation. 4 vols. Ankara: Yeni Türkiye, 2000; Daly, M. W., ed. Cambridge History of Egypt. 2 vols. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1998; Esposito, John, ed. The Oxford History of Islam. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999; Kiel, Machiel. Art and Society in Bulgaria of the Turkish Period. Maastricht: Van Gorcum, 1985; Milstein, Rachel. Miniature Painting in Ottoman Baghdad. Costa Mesa, Calif.: Mazda, 1990; Scarce, Jennifer M., ed. Islam in the Balkans: Persian Art and Culture of the 18th and 19th Centuries . Edinburgh: Royal Scottish Museum, 1979; Spring, Christopher, and Julie Hudson. North African Textiles. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995.

Ottoman Art

Ottoman art often defied the Islamic taboo of representing animals and human figures. Muslims in the Ottoman and Persian Empires in the 15th and 16th centuries produced a wonderful collection of art representing episodes from Mohammed’s life complete with images of Mohammed, angels, animals and ordinary people. Ottoman sultans commissioned portraits of themselves and illustrated records of historical events and battles. Titian painted a portrait of Süleyman the Magnificent and Gentile Bellini painted Mohammed II. The public however did not know about these works of art. It was rationalized that it wasn't necessarily a sin to possess these works of art, it was only a sin to display them ostentatiously. This same reasoning was used to justify gambling, drinking, the making of eunuchs and womanizing (also against Muslim law) in private.µ

All the sultans were required to master a “trade,” usually a craft such as calligraphy or goldsmithing. The most esteemed artists belonged to the “nakkashane”, the imperial studio that produced manuscripts for the sultan’s libraries. They developed new and original styles that helped define their art form and also had a major impact on other art forms.

One of the most important Ottoman styles of art was “saz”, meaning “an enchanted forest.” It evolved from drawings of mythical creatures engulfed in foliage, fantastic flowers and long twisting leaves. The designs and patterns were first used to adorn Korans and manuscript illuminations and then was used to decorate almost all other art forms from small ivory sculptures to robes worn by the sultan.

A second notable style featured displays of identifiable flowers such as tulips, carnations, roses, hyacinths and fruit blossoms. These too were first used to decorate manuscripts and then spread to other art forms. Both styles were developed by the masters at nakkashane.

Calligraphy was regarded as the noblest of the arts. Several sultans chose it as their “trade.” The most gifted calligraphers made imperial Korans for the sultans and architectural inscriptions for great mosques. Among the most highly values forms of calligraphy were “museelsel”, in which an entire phrase was rendered without lifting a pen; and “makil kufi”, the angular script written in a square format.

Some of the greatest treasures of Ottoman art are manuscripts and Korans distinguished by the exquisiteness of their calligraphy and the beauty of the of their illustrations and illuminations. The most beautiful Korans were kept with the sultan or placed in his treasury. The arts of calligraphy and illustration were also were also demonstrated in poems, imperial albums, and historical documents.

See Islamic Art, Topkapi

Treasury of Topkapi Palace

Topkapi diamond

The Topkapi Treasury houses a stunning assemblage of gems equaled only by the Crown Jewels in Britain and the Shah's treasures in Iran. The buildings now occupied by the treasury are where the sultan lived. Some of the museum's treasures, such as rotating music boxes and solid silver elephants from India, were gifts from foreign dignitaries to the sultans. Some, like the gem encrusted Korans, were gifts from pashas under the sultan controls. And others were spoils of war.

Yet others were crafted by palace craftsmen and artists. Among the 575 artisan who worked at the palace in 1575 were goldsmiths, engravers, furriers, potters, musical instrument makers, calligraphers, weavers, painters and bookbinders from Turkey, Herat, Tabriz, Cairo, Bosnia, Hungary and Austria. The sultans often oversaw the work by the craftsman The sultans were all trained in a particular trade and sometimes produced their own works of art.

Treasures in the Treasury include silver and gold belts lined with emeralds the size of quail eggs; shields rimmed with pearls and precious stones; exquisitely carved mirrors of ivory; and quivers made of silk and yet more gems. Even the water canteen the sultan took with him to battle is something to behold. It is made of 4.5 pounds of gold and imbedded with rubies, emeralds and diamonds. Not all the red stones in the treasury are real rubies and not all the clear ones are diamonds.

Other goodies in the treasury include the diamond encrusted armor of Mustafa III, an 18th century gold hookah, and a jewel encrusted cradle where newborn princes were presented to the sultan. There is a jade mug encrusted with rubies and emeralds and a figure of a sultan carved from an enormous pearl. The 86-carat diamond inside a glass vault, the story goes, was found by a fisherman, who traded it for three spoons. The reliquary of St. John the Baptist's arm has a square opening so you can see the bone inside.

The 16th century walnut, ivory and ebony throne was used by Sulyeman the Magnificent. Inlaid with gold, jewels, mother of pearl and tortoise shell, it is appreciated more for its detailed craftsmanship than European sumptuousness. It was made with special cushions so the sultan could sit cross legged on it.

Emerald Treasures and Islamic Relics at Topkapi

Topkapi dagger

The emerald treasures in the Treasury are especially dazzling. These include an emerald-plated snuff box and a gold writing box with emeralds and rubies. The 18th century emerald-studded dagger featured in the Orson Wells film has three golf-ball size emeralds and rows of diamonds on the handle. A forth large emerald conceals a small clock. The dagger was originally meant to be a present for the Nadir Shah of Iran. He was assassinated before the gift could be presented to him so the sultan kept it.

The emerald pocket watch was also supposed to be a gift from the Turkish sultan to the ruler of Persia, but the messenger died before he got to Iran and somehow the watch made its way back to Istanbul. Most of the magnificent emeralds came from Columbian mines via Spain and India in the 17th and 18th century. "Diamond-loving Europeans were at first not very found of emeralds," says gemologist Fred Ward, " which is one reason why the Ottomans...ended up with so many monstrous stones."

In the Pavilion of the Holy Mantle (center of the third courtyard), through another series of gates, you can see treasures looted from Mecca and Medina, when Ottoman sultans were the protectorate of Islam's holiest cities. Inside one display case is a tooth and a couple of strands of hair purported to be from the Prophet Mohammed himself. You can also lay eyes upon a couple of his swords and his massive Shaquille-O'Neal-size footprint. In another chamber is a part of the silver casing from the black stone of the Kaaba, an artifact that is as holy to Muslims as the True Cross or the Holy Grail is to Christians. An imam, or Muslim holy man, is inside a glassed off chamber with many of these relics, chanting prayers around the clock, something you won't see in Louvre or the Hermitage. The collection is housed in the Privy Chamber, where the sultan lived and kept his throne among gleaming domes and walls decorated with Iznik tiles. The light is kept dim out of respect to the holy objects kept here.

Art and Architecture of the Ottomans before 1600

Suzan Yalman of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “In the arts, there is a paucity of extant objects from the early Ottoman period, but it is apparent from surviving buildings that Byzantine, Mamluk, and Persian traditions were integrated to form a distinctly Ottoman artistic vocabulary. Significant changes came about with the establishment of the new capital in former Byzantine Constantinople. After the conquest, Hagia Sophia, the great Byzantine church, was transformed into an imperial mosque and became a source of inspiration for Ottoman architects. [Source: Suzan Yalman, Department of Education, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, based on original work by Linda Komaroff metmuseum.org \^/]

Qu'ran box

“Mehmed II ("the Conqueror," r. 1444–46, 1451–81) envisaged the city as the center of his growing world empire and began an ambitious rebuilding program. He commissioned two palaces (the Old and the New, later Topkapi, palaces) as well as a mosque complex (the Mehmediye, later Fatih complex), which combined religious, educational, social, and commercial functions. In his commissions, Mehmed drew from Turkic, Perso-Islamic, and Byzantine artistic repertoires. He was also interested in developments in western Europe. Ottoman, Iranian, and European artists and scholars flocked to Mehmed's court, making him one of the greatest Renaissance patrons of his time. \^/

“Under Mehmed's successors, his eclectic style, reflective of the mixed heritage of the Ottomans, was gradually integrated into a uniquely Ottoman artistic vocabulary. Further geographic expansion brought additions to this vocabulary. Most significantly, the victory against the Safavids at a battle in eastern Anatolia (1514) and the addition of Mamluk Syria, Egypt, and the Holy Cities of Islam (Mecca and Medina) to the Ottoman realm under Selim I ("the Grim," r. 1512–20), led to the increased presence of Iranian and Arab artists and intellectuals at the Ottoman court. \^/

“During the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, developments occurred in every artistic field, with those in architecture, calligraphy, manuscript painting, textiles, and ceramics being particularly significant. Apart from Istanbul, various cities in the provinces were also recognized as major artistic and commercial centers: Iznik was renowned for ceramics, Bursa for silks and textiles, Cairo for the production of carpets, and Baghdad for the arts of the book. Ottoman visual culture had an impact in the different regions it ruled. Despite local variations, the legacy of the sixteenth-century Ottoman artistic tradition can still be seen in monuments from the Balkans to the Caucasus, from Algeria to Baghdad, and from Crimea to Yemen, that incorporate signature elements such as hemispherical domes, slender pencil-shaped minarets, and enclosed courts with domed porticoes.” \^/

Books: Atil, Esin, ed. Turkish Art. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1980. Goodwin, Godfrey A History of Ottoman Architecture. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1971.

Art and Architecture Under Süleyman the Magnificent

Suzan Yalman of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Along with geographic expansion, trade, economic growth, and tremendous cultural and artistic activity helped define the reign of Süleyman as a "Golden Age." Developments occurred in every field of the arts; however, those in calligraphy, manuscript painting, textiles, and ceramics were particularly significant. Artists renowned by name include calligrapher Ahmad Karahisari as well as painters Shahquli and Kara Memi. [Source:Suzan Yalman, Department of Education, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, based on original work by Linda Komaroff metmuseum.org \^/]

drawer

“In architecture, the most outstanding achievements of this period were the public buildings designed by Sinan (1539–1588), chief of the Corps of Royal Architects. While Sinan is often remembered for his two major commissions, the mosque complexes of Süleymaniye in Istanbul (1550–57) and of the later Selimiye in Edirne (1568–74), he designed hundreds of buildings across the Ottoman empire—300 structures in Istanbul alone—and contributed to the dissemination of Ottoman culture. Apart from mosques and other pious foundations—including schools, hospices, and soup kitchens, supported by shops, markets, baths, and caravanserais—Süleyman also commissioned repairs and additions to major historical monuments. The tile revetment of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, as well as several additions to sites in Mecca and Medina, the two Holy Cities of Islam, date from this period.

“In the period following Süleyman's death, architectural and artistic activity resumed under patrons from the imperial family and the ruling elite. Commissions continued outside the imperial capital, with many pious foundations established across the realm.”

Books: Atil, Esin The Age of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent. Exhibition catalogue.. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1987. Necipoglu, Gülru The Age of Sinan: Architectural Culture in the Ottoman Empire. London: Reaktion, 2005.

Art and of the Ottomans after 1600

Marika Sardar of New York University wrote: “In the early seventeenth century, both Ottoman book production and architecture remained traditional. The court scriptorium continued to produce its established series of texts—biographies, travel accounts, genealogies, and geographies—many of which were illustrated or illuminated. The Mosque of Ahmed I in Istanbul (1609–16), also known as the "Blue Mosque" because of the interior tile scheme, continues in the vocabulary of the great architect Sinan (1539–1588). [Source: Marika Sardar Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“Later in the century, a weakening Ottoman economy began to affect the arts. An influx of gold and silver from the New World caused inflation and the treasury shrunk without military victories and booty to refill the coffers. The sultans were forced to reduce the number of artists they employed in the nakkashane (royal scriptorium) to ten from the high of over 120 in the time of Süleyman the Magnificent (r. 1520–66), and for many years did not increase the set prices they paid for ceramics, paintings, and carpets. It became more profitable for artists to produce items for the open market than to be tied to the workshops of the low-paying court, and sultans had to pass edicts forcing them to finish imperial commissions. One of the few arts that maintained a high level of quality was calligraphy. Hafiz Osman (1642–1698) was the master of this era, teacher to Sultan Mustafa II (r. 1695–1703) and his son, Sultan Ahmed III (r. 1703–30). \^/

“Under Ahmed III the arts revived. He built a new library at the Topkapi Palace and commissioned the Surnama (Book of Festivals, ca. 1720, Topkapi A.3593), which documents the circumcision of his four sons as recorded by the poet Vehbi. The paintings detail the festivities and processions through the streets of Istanbul, and were completed under the direction of the artist Levni (d. 1732), whose work is also known from a set of portraits collected in a Murakka (Topkapi H.2164). While his style was traditional, other artists of his time were greatly affected by the European prints and engravings that began to circulate in Ottoman lands. \^/

“Ahmed’s reign is also known as the Tulip Period. The popularity of this flower is reflected in a new style of floral decoration that replaced the saz style of ornament with serrated leaves and cloud bands that had characterized Ottoman art for many years, and is found in textiles, illumination, and architectural ornament. The architecture of this period is exemplified in the monumental fountain constructed by Ahmed III outside the gate to the Topkapi Palace. Ambassadors dispatched to Paris and Vienna sparked further changes with their descriptions of the Baroque architecture of Versailles and Fontainebleau, but many of the Baroque-inspired palaces built during Ahmed’s reign were destroyed in the revolt that forced him to abdicate in 1730. The earliest building to survive is the Nur-u Osmaniye Mosque (1748–55), begun by Mahmud I and finished by Osman III. Its flamboyant decoration, ornate moldings, and vegetal carvings are the hallmark of the style that continued into the nineteenth century. \^/

Books: Atil, Esin, ed. Turkish Art. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1980. Goodwin, Godfrey A History of Ottoman Architecture. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1971.

Blue Mosque in Istanbul

Europeanization of Ottoman Art

Marika Sardar of New York University wrote: “The Ottoman sultans' fascination with European art, which had so strongly influenced the arts of the eighteenth century, played an equally important role in the nineteenth. Just as they attempted to solve the empire's problems with the adoption of European systems of law, military, and even dress, so European-style art seemed the most appropriate form of expression for what the country perceived as its own modern and cosmopolitan culture.[Source: Marika Sardar Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“Painting with oil on canvas became very popular, superseding the production of small-scale paintings for manuscripts and albums. Military schools were the first to produce practitioners of this form, educating their recruits in the arts so that they could produce detailed topographical surveys and technical drawings, and many officers became accomplished landscape painters. Among the earliest schools to offer such training was the Imperial School of Military Sciences, which opened in 1834. Several of the European military experts hired by the school were asked to teach painting as well, but eventually Turkish students were sent directly to art schools in Europe so that they could return to teach in Turkey themselves. \^/

“The painters Osman Hamdi (1842–1910) and Seker Ahmet Pasha (1841–1907) clearly supported Europeanization, as evidenced by Hamdi's wholehearted assimilation of the French Orientalist mode of painting and Seker Ahmet's Western-style landscapes and still lifes. Son of an Ottoman grand vizier and ambassador, Hamdi was one of many students to receive a scholarship to study in Europe. He trained with the painters Gustave Boulanger (1824–1888) and Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824–1904), and enjoyed a successful career in Paris until his 1868 return to Istanbul. Abdülhamid II learned photography and took a special interest in it. He ordered photographers to record all state occasions and important architectural structures, and to take portraits of notable political personages.” \^/

“In this period, some artists were dedicated to painting portraits, including Prince Abdülmecid Efendi (1868–1944), cousin of Abdülhamid, while others worked in the now-established landscape painting genre. Artists in this period looked to contemporary Europe for inspiration, and began to organize their own exhibitions. One such group who painted in the Impressionist style formed around the artist Ibrahim Çalli (1882–1960). They later took the name Association of Ottoman Painters, and published a monthly journal and held annual exhibitions.” \^/

Books: Atil, Esin Levni and the Surname: The Story of an Eighteenth–Century Ottoman Festival . Istanbul: Koçbank, 1999. Renda, Günsel, et al. A History of Turkish Painting. Geneva: Palasar, 1987.

Ottoman sabres

Europeanization of Ottoman Culture

Marika Sardar of New York University wrote: “Mahmud's success in eliminating the Janissary corps from the army occasioned other advances in the arts. His first move was to convert the traditional band that had accompanied the troops into a Western-style orchestra. He also commissioned the Nusretiye Mosque in Istanbul to commemorate this 1826 achievement. The foreign-trained Armenian chief royal architect Krikor Balyan (1764–1831) designed the building in the French Empire style and adjoined a two-story royal apartment with ornate moldings to the traditional Ottoman domed prayer hall. Balyan also designed the Selimiye barracks that replaced the soldiers' quarters burned in the 1808 Janissary insurrection. Later sultans expanded the structure, and parts were used as Florence Nightingale's hospital during the Crimean War (1853–56). \^/ [Source: Marika Sardar Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“European influence also extended to literature, where new prose forms like the novel and the play provided the means for experimentation and for expressing the personal effects of the state's modernizing campaigns. Journalistic writing evolved with the arrival of foreign reporters during the Crimean War; with their influence, the first nonofficial newspapers began to appear, and these became another important forum for the expression of social commentary. But the most significant development of this period was the introduction of photography. It arrived in Istanbul in the early 1840s, and soon a number of commercial photographers such as J. Pascal Sébah (1823–1886) opened studios in the capital. The military also made use of this new medium, and official photographers were employed by the various defense ministries of the empire. Photographs also often served as models for painted portraits, landscapes, and still-lifes. \^/

“This age also saw the dawn of journalism. Several European communities in Turkey had begun to print newspapers in their own languages in the late eighteenth century. The first official Turkish paper was launched in 1831. Meanwhile, the First National Architectural Style was developing. It proposed an updated image of the Ottoman state with a combination of elements from the Neoclassical and Orientalist vocabularies, and is exemplified in the works of the European professors teaching at the Academy of Fine Arts. A. Jachmund's 1890 Sirkeci Railroad Terminus for the Orient Express, for instance, features the horseshoe arches of Spain and the striped masonry of Mamluk architecture together with the chatris (memorial structures) of Indian design. \^/

Working in the early twentieth century, the students of Jachmund and Antoine Vallaury focused more specifically on their Turkish heritage, creating an "Ottoman Revivalism" that involved an eclectic collection of elements from European and classical Ottoman architecture. Examples include Vedat Bey's (1873–1942) Defter-i Hakani, built in 1908, and Kemalettin's (1870–1927) Fourth Vakif Han of 1912–26, both in Istanbul. The latter's cut-stone facade and steel skeleton structure come from the European tradition, but its geometric carving, tiled panels, and lead-covered domes all derive from the Ottoman past. \^/

Ottoman plate

“The nineteenth-century European developments of the museum and the modern study of art history were immediately taken up in Turkey. Osman Hamdi figured large in this scene as well; he founded the Academy of Fine Arts in 1883, initiated excavations at several sites, and put into place laws against antiquities trafficking. He was also director of the Imperial Ottoman Museum that opened at the Çinili Kiosk of the Topkapi Palace in 1881. It presented materials from Turkey's ancient and classical past, while the Islamic Museum (later called the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Art) opened in 1914 at the Süleymaniye Mosque complex to display those aspects of the country's Islamic heritage.” \^/

Silks from Ottoman Turkey

Nazanin Hedayat Munroe of the Metropolitan Museum Art wrote: “Ottoman silk textiles are among the most elegant textiles produced in the Islamic world. They are characterized by large-scale stylized motifs often highlighted by shimmering metallic threads. Executed in a range of woven techniques including satin and velvet, these silks were produced for use both within the Ottoman empire and for export to Europe and the Middle East, where they were considered among the most prized luxury objects. Ottoman textiles produced during this period are unsigned; while we have some data about the inner workings of royal or independent workshops that operated under the guild system, we cannot attribute particular textile designs to individuals or workshops. [Source: Nazanin Hedayat Munroe Department of Islamic Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org\^/]

“The stylized floral designs now emblematic of the classical Ottoman style were developed during the reign of Süleyman I, also known as Süleyman the Magnificent (r. 1520–66), as an alternative to the "International Style" that prevailed in the area during the early period of rule from the mid-fifteenth to mid-sixteenth centuries. Textile designs feature iconography shared with other decorative media designed by the nakkashane (royal design atelier) and adapted to the constraints of the loom to create elegant repeat patterns. The most popular layouts ranged from floral motifs characterized by wavy vertical stems with blooming palmettes (52.20.21), carnations, or pomegranate fruit (52.20.19), to large-scale ogival layouts with delicate peony blossoms creating a lattice pattern (49.32.79). Lattice layouts became popular during the reign of Süleyman I and may also reflect layouts and motifs used in architectural tile decoration from Iznik, or earlier Mamluk silks themselves inspired by Chinese examples. \^/

“The so-called saz style (52.20.17) was also incorporated into textile design, featuring the sinuous outlining of motifs and jagged edges on leaves and flowers. Associated with court painter Shah Qulu, an émigré from Iran who served at the court of Süleyman I, saz motifs remained in use throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Kara Memi, Shah Qulu's top pupil and successor as head of the nakkashane, added to the painter’s repertoire by developing a stylized iconography of floral motifs including carnations, roses, tulips, hyacinth, and cherry blossoms. These remained favorite motifs throughout the “Tulip Period” of Ahmed III (r. 1703–30). \^/

Ottoman embroidered silk towel

“Another popular decorative motif reproduced on textiles is the chintamani design (08.109.23), usually depicted as two wavy horizontal bands alternating with three circles in triangular formation. Translated from Sanskrit as “auspicious jewel,” the motif originated in Buddhist imagery, including the paintings at the Central Asian Magao caves (ca. 1000 A.D.), and may represent pearls and flames. The design elements of chintamani are alternately referenced as “tiger stripes” and “leopard spots.” Similar iconography is found in sixteenth-century Persian manuscript paintings featuring the Shahnama's hero, Rustam, who wears a garment of tiger skin and a leopard-skin hat depicted in a similar fashion, and possibly represents the fabric in Ottoman documents called pelengi (leopardlike) or benekli (dotted). Occasionally, chintamani is combined with floral elements (44.41.3) in a delicate balance of the two distinctive styles, or the wavy lines and circular elements are separated to create singular motifs (15.125.7). In any combination, elements of chintamani were believed to protect the wearer and to imbue him with physical and spiritual fortitude.” \^/

Ottoman Silk Trade and Production

Nazanin Hedayat Munroe of the Metropolitan Museum Art wrote: “Bursa was the first capital of the Ottoman state (1326–65) and already an important entrepôt on the Eurasian trade route, allowing the Ottomans to function as middlemen in the trade of raw silk. Cocoons or undyed silk thread produced in Safavid Iran's northern provinces of Gilan and Mazandaran passed through these territories; they were weighed on government-controlled scales and a further tax was levied on materials purchased by European merchants (who were mostly Italian). A decline in the export of Iranian raw silk in the mid-sixteenth century due to political strife instigated the beginnings of domestic sericulture in the Ottoman state, and from that point onward there was a larger variety of the quality of silk and fiercer competition for the European market. [Source: Nazanin Hedayat Munroe Department of Islamic Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“Ottoman weaving workshops in Bursa were well established by the fifteenth century, producing the majority of Ottoman luxury velvets (çatma) and metal-ground silks (seraser or kemha) for export as well as for domestic markets. Compound weave structures consisting of two warps and two or more complementary wefts (seraser, or taqueté) continued to be a preferred pattern structure, while structures such as lampas (kemha), combining twill and satin weaves, were added to the repertoire. Textile workshops under court control in Istanbul were focused on producing cloth of gold and silver (seraser) for use as clothing and furnishings in the imperial palace and honorific garments (hil'at) (2003.416a-e) given to courtiers and foreign ambassadors. Woven silks purchased by European merchants often ended up in palaces or churches throughout Europe as secular or ecclesiastical garments (06.1210) worn by high-ranking officials or used to encase relics. \^/

“As the central power of the Ottoman state in Istanbul began to wane in the later seventeenth century, royal workshops and commissions began to falter. Textiles once protected by sumptuary laws and produced solely for use by the court began to appear in the bazaar for sale to anyone who could afford them. The upwardly mobile middle class began appropriating the dress and style of the aristocracy, while private workshops took over much of the production of silks.” \^/

Ottoman Silk Textiles in Context

Ottoman silk-and-metal threaed brocaded fabric

Nazanin Hedayat Munroe of the Metropolitan Museum Art wrote: “Most Ottoman silks produced for use within the empire were used either for garments or furnishings. The outer garments for Ottoman men incorporated trousers and a matching kaftan (52.20.15), a floor-length crossover robe or sleeveless vest, perhaps adapted from traditional tribal riding costumes of the Central Asian and Iranian steppes. The Ottoman sultans were known for their elaborate ceremonies and parades in the capital of Istanbul, during which every member of the court, from child princes to janissaries, would be clothed in a new garment for the occasion. In this context, the large-scale patterning of ogival lattice designs and chintamani would have provided maximum impact. Women’s garments were typically the same style, with more layering, slightly more tailoring, and smaller-scale patterns. The extensive documentation and storage of Ottoman garments and hangings in the Topkapi Palace provide historians with contextual information and extant examples for analysis. [Source:Nazanin Hedayat Munroe Department of Islamic Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“Textiles used for furnishings included cushion covers (yastik, 17.120.123) for seating in the reception rooms (selamlik) in palace pavilions and upper-class homes, as well as interiors for tents during military campaigns. Yastik panels were often designed to fit the width of the loom so multiple covers could be cut to exact dimension from a single bolt without sacrificing any of the precious material. \^/

“Epigraphic panels were also woven and embroidered with Qur'anic text for use as architectural coverings. The Ottoman sultans produced a new kiswa for the Ka'ba every year in Mecca during hajj, the month of pilgrimage, which featured large-scale gold embroidery. Textile panels woven with Qur'anic inscriptions were also used as cenotaph covers (32.100.460). \^/

“While Ottoman painting workshops produced manuscripts that include figural compositions, the Ottoman textile industry almost never produced figural silks, in sharp contrast to this specialty of the textile industry in contemporary Safavid Iran. Scholars continue to debate the motivation for excluding figures from textile motifs. The arguments range from Sunni debates on figural representation to sumptuary regulations in various firman (edicts) issued by sultans. Unlike Safavid examples that bear designers' names, Ottoman textiles produced during this period are unsigned; while we have some data about the inner workings of royal or independent workshops that operated under the guild system, we cannot attribute particular textile designs to individuals or workshops. \^/

Image Sources:

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History “ by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples “ by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures “ edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994). Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, BBC, Al Jazeera, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018