GENGHIS KHAN

Genghis Khan (1162-1227) was the first and greatest of the Mongol khans. He believed that it was heaven's will and his destiny to unite the world by force. Forging an army from a group of unruly Mongol tribes, he almost single-handedly created an empire that spanned half of the known world. J.M. Roberts, author of the Penguin History of the World called him “the greatest conqueror the world has ever known," [Source: Mike Edwards, National Geographic, December, 1996]

Genghis Khan is a Persianized spelling of Chinnis Khaan, (or sometimes Chinggis Khan, Chingiz Khan or Jenghiz Khan) the name by which he is known in Mongolia. According to legend Genghis Khan was born with “fire in his eyes and a light on his face.” A Persian historian wrote he was "possessed great energy, discernment, genius, and understanding, awe-inspiring, a butcher, just, resolute, an overthrower of enemies, intrepid, sanguinary, and cruel."

According to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art: “At the time of his death in 1227, Genghis Khan had unified the Mongol people, organized a nearly invincible army of fearless nomadic warriors, and set into motion the first stage in the conquest of an enormous territory that would be completed by his sons and grandsons. With extraordinary speed and devastating ruthlessness the Mongols created the world’s largest empire, stretching at its greatest extent from Korea to Hungary. But the legacy of Genghis Khan extends well beyond the battlefield. [Source: “The Legacy of Genghis Khan: Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256-1353", Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2003 exhibition]

Genghis Khan is reputed to have said; “ The greatest joy a man can have is victory: to conquer one’s enemy’s armies, to pursue them, to deprive them of their possessions, to reduce their families to tears, to ride their horses, and to ravish their wives and daughters.” But not everyone sees him as a villain. Russian director Sergei Bidrov, who made a movie about him, said: “I realized he wasn’t born a monster. He was orphaned, he was a slave, he met his future wife when he was 9. He punished anyone who tortured prisoners and was loyal to his people. Nobody betrayed him. Alexander the Great’s empire fell after he died.. Genghis Khan’s lasted for 200 more years.

Many of the accounts about Genghis Khan and his exploits come from the anonymously-written "The Secret History of the Mongols”, which was written not long after Genghis Khan’s death and has been described as the Mongolian version of the "Odyssey”. Among other things this book reports that Genghis Khan was afraid of dogs and was born in a region of Mongolia about 200 miles northeast of Ulaan Baatar. The book today is required reading for Mongolian school children.

Books: The best modern work on Genghis Khan is “Genghis Khan: His Life and Legacy” by Paul Ratchnevsky, trans. by Thomas Haining (Oxford: Blackwell, 1991). Other books include “The Legacy of Chinggis Khan” by Patricia Berger and Terese Tse Bartholomew (Thames and Hudson);. The medieval text “History of the World Conqueror” by Ala-ad-Din-Ata-Malik book is considered one of the best sources of information on Genghis Khan's military campaigns.

Websites and Resources: Mongols and Horsemen of the Steppe:

Wikipedia article Wikipedia ;

The Mongol Empire web.archive.org/web ;

The Mongols in World History afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols ;

William of Rubruck's Account of the Mongols washington.edu/silkroad/texts ;

Mongol invasion of Rus (pictures) web.archive.org/web ;

Encyclopædia Britannica article britannica.com ;

Mongol Archives historyonthenet.com ; “The Horse, the Wheel and Language, How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes shaped the Modern World", David W Anthony, 2007 archive.org/details/horsewheelandlanguage ; The Scythians - Silk Road Foundation silkroadfoundation.org ;

Scythians iranicaonline.org ;

Encyclopaedia Britannica article on the Huns britannica.com ; Wikipedia article on Eurasian nomads Wikipedia

Myths and Sources on Genghis Khan

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “More has been written about Genghis Khan than perhaps any figure in Asian history, but much of this has been misleading, inaccurate, or prejudicial. Many Westerners accept the stereotype of Genghis as a barbaric plunderer intent on maiming, slaughtering, and destroying other peoples and civilizations. To the Mongols, however, Genghis Khan is a great national hero who united all the Mongol tribes and carved out the largest contiguous land empire in world history. And according to this latter view, Genghis and his descendants promoted frequent and extended contacts among the civilizations of Europe and Asia, ushering in an era of extraordinary interaction of goods, ideas, religions, and technology. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols ]

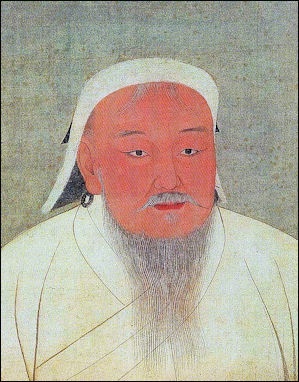

“Often based on secondary accounts and myths that cannot be attested, these divergent views usually bear scant relation to what we find in the limited primary sources on Genghis Khan that have survived to this day. Many Westerners are unaware, for instance, that "Genghis Khan" is a title and that his birth name was Temujin. In addition, no contemporaneous portrait of Genghis Khan has survived in any painting or in any other visual media.

“Surprisingly few reliable accounts about Genghis Khan have been discovered. The Secret History of the Mongols is one that presents a contemporaneous Mongol perspective. The author (or authors) are anonymous, and the date of the work's completion is unknown, but it is certainly a 13th-century work and offers, together with self-serving myths, the most complete account of Genghis's life and career.

“The Persian historian and official Ala-ad-Din Ata-Malik Juvaini (1226?-1283), who served at the Mongol court in West Asia, wrote the best description of Genghis's campaigns. His work is generally judicious — it is (in his own words) "on the one hand, [a] candid recital of Mongol atrocities, [a] lament for the extinction of learning, [a] thinly veiled criticism of the conquerors and... [an] open admiration of their vanquished opponents; and on the other hand, [in] praise of Mongol institutions and Mongol rulers and [a] justification of the invasion as an act of divine grace." Genghis also invited a Daoist sage named Changchun to accompany him on his campaigns to Central Asia, and he wrote a fine, first-hand description of his Mongol patron that yields fascinating insights into his personality.”

Family and Tribal Background of Genghis Khan

After the migration of the Jurchen, the Borjigin Mongols had emerged in central Mongolia as the leading clan of a loose federation. The principal Borjigin Mongol leader, Kabul Khan, began a series of raids into Jin in 1135. In 1162 (some historians say 1167), Temujin, the first son of Mongol chieftain Yesugei, and grandson of Kabul, was born. Yesugei, who was chief of the Kiyat subclan of the Borjigin Mongols, was killed by neighboring Tatars in 1175, when Temujin was only twelve years old. The Kiyat rejected the boy as their leader and chose one of his kin instead. Temujin and his immediate family were abandoned and apparently left to die in a semidesert, mountainous region. [Source: Library of Congress, June 1989 *]

Yesugei Baghatur, Genghis's father

Genghis Khan, whose name is Temujin (also called Te Meizhen, Tie Muzhen, Te Mujin), is a member of Nilunmengguqiyan Boerzhijin clan. He was born in Dieliwen Boledahe (today, it is in Dadale, Kent province, Mongolia). When he was born, his father Yesugaibaatuer (1125---1171) had just defeated the Tatars, and seized their leader Temujin Wuge. To memorialize this victory, his father named him Temujin (transliteration of Mongol, meaning "iron", "like iron"). According to “Mongol Secret History”, when Temujin was born, he held a big gore in his hand, which indicated his extraordinary fate and future. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, kepu.net.cn ~]

Early Life of Genghis Khan

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Genghis (Chinggis) Khan was born probably in 1167, though Mongol tradition has it that he was born in 1162. Because much of his early life is not described, except in myth, reliable knowledge of Genghis's early life is very limited.What we do know is that his father was assassinated when Genghis was nine years old, and that this event left his family extremely vulnerable. Genghis's mother appears in the traditional Mongol sources as a savior and great heroine. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols ]

According to the Chinese government: "When Temujin was 9 years old, his father was poisoned by the Tatars. The Boerzhijin clan lost their leader, and Temujin lost his backer. The clansman dispersed one after another, and their properties were ransacked. The family had to make their livings by fishing, mousing, and picking wild fruits. Still, some forces like Taiyichiwu didn't let them pass, and they were afraid that when the Temujin brothers grew up, they would revive their family force, and that would be a threat to their status and interests. Thus, they sent arms to capture Temujin, and wanted to "cut the weeds and dig up the roots" and put an end to the future trouble. Fortunately, Temujin was saved by a kind-hearted man Suoerhanshila, and escaped from danger. In such difficult and dangerous environment, Temujin's family had endured all hardships, but at the same time, his willpower was tempered, and his brave and fearless spirit in fighting was cultivated." ~

Genghis Khan's Birthplace

Delun Boldog

Genghis Khan was named Temüjen (meaning "blacksmith") after a Tatar chief his father had just killed. He was born in the 1160s, purportedly with a clot of blood in his hand (a good omen to the Mongols). His officials date of birth is 1162 but estimates of when he was really born vary form 1155 to 1167. Describing the origin of Genghis Khan, "Secret History" reports, 'There was once a blue-gray wolf who was born with his destiny preordained by Heaven Above. His wife was a fallow doe."

The exact location of Genghis Khan's birthplace and his burial place are unknown but we do know that he was raised in the upper regions of the Onon (Orkhon) River, a forested region rich in game. Many Mongolians believe that he was born in a valley called the Gurvan Nuur where there is a spring where he washed and a pine-cloaked mountain where he prayed.

Around the time of Genghis Khan's birth, Mongolia was inhabited by 1.5 to 3 million people who were divided among several dozen Turkic- and Mongol-speaking tribes. The same general region is believed to have also given birth to the Huns, Turks and Xiongnu (a people that had raided China for centuries).

Dadal (350 miles northwest of Ulaan Baatar) is the purported birthplace of Genghis Khan. Also known as Bayan Ovoo, it is a small village in Khentii province surrounded by beautiful forests, mountains and lakes. More than 43 sites associated with Genghis Khan have been identified in the region, including the place where he was crowned and the place he formed his army. Huddu Aral is sometimes described as the home of the “Palace of Genghis Khan.” Encircled by the Herlen and Tsenheriin rivers and the Herlen Bayan Ulaan Mountains, it is a grass plain about 30 kilometers long and 20 kilometers wide, at an elevation of 1,300 meters. The site of the Ikh Auring (Palace) of Genghis Khan was on this plain according to the "Secret Life of the Mongols". The remains of fortifications can be found here.

Genghis Khan's Family

Genghis Khan was orphaned when he was 13. According to one story Temüjen's father, a petty warlord and tribal chieftain, was poisoned by Tartars when Temüjen was nine and according to another story he died in combat while a 12-year Temüjen hid in a lake breathing from a hollow reed.

Temüjen’s father, Yessugei, was the leader of the Kiyat-Borjigin tribe, who homeland was at the source of the Onon River and before that southern Siberia. Many think that Genghis Khan’s family were not even Mongols but were Buriats, a Mongol-related group more associated with the Orkhon River area than the Mongols.

After the his father death, Temüjen, his mother and the rest of his family enduring a number of hardships. According to "Secret History", they became so poor they had to eat rats, marmots, berries and insects to survive. Temüjen was constantly on the run from family rivals determined to extinguish his family line. An early sign of his propensity to violence was the killing of his half brother Bekter for stealing one of his fish while still a teenager.

According to the Chinese government: Later, with the help of his father's sworn brother Wang Han, he gathered his men, accumulated his forces and started his carving out process. In 1185, he defeated Mieerqi. In 1189, he was elected as Khan by the noble class of Qiyan family. After that, he spent more than ten years on expedition.

Genghis Khan, his wife and nine sons

As for his own immediate family and offspring, Genghis Khan had six Mongol wives, at least two of whom were sisters. The heirs to Genghis Khan empire---his sons, Jochi, Chaghatai, Ogodi and Tolui---were all born to his first wife Borte of the Konggirait tribe. Genghis had been betrothed to Borte since they were children and were married when they teenagers. The legitimacy of Jochi was always of a matter of question because he was born nine months after Borte was kidnapped (See Below). Genghis Khan eventually accumulated 500 wives and concubines from his foreign conquests.

Genghis Khan’s Mother Teaches Him About Survival

According to the Chinese government: "The adamant mother Keelun always told Temujin brothers the importance of tenacity and diligence, and let them know the truth that "Solidarity is force". Thus, Temujin made up his mind that he would avenge his father and build upon his ancestral achievement."

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Genghis's mother appears in the traditional Mongol sources as a savior and great heroine. Genghis's mother kept her family together, even after many of her retainers left when her husband, the family patriarch, was killed. She kept the family going in the harsh desert lands of Mongolia, surviving on nuts and berries or whatever else they could find. She taught Genghis the basic skills of survival, particularly those needed for survival in the steppelands and in the desert. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols ]

After Genghis’s father died, most of his family’s herds were stolen, so that his mother had to feed her children edible plants: wild pears, bird cherries, garden burnet root, cinquefoil root, wild onion, shallot, lily root, and garlic chives. Despite this diet of what the Mongols considered second-rate foods, Genghis and the other boys “grew up into fine men” in the words of the Secret History.” [Source: “Dietary Decadence and Dynastic Decline in the Mongol Empire” by John Masson Smith, Jr., University of California, Berkeley, Journal of Asian History, vol. 34, no. 1, 2000]

Genghis Khan Gains Control of His Clan

Genghis Khan began with just a handful of fighters. While still in his teens Temüjen made a name a name for himself with his daring raids on neighboring tribes and gained the allegiance of disgruntled warlords.. He becomes a blood brother with a man named Jamuqa (Jamukha) and befriended the leader of the Kereyit tribe, a man named Toghril. Both young men helped Temüjen rescue Borte when she was kidnaped.

According to one story, Temujin returned home from hunting one day to find that his wife had been kidnaped by a rival clan, the Merkit tribe. Calling an old family debt of honor, he raised a small band of armed men, freed his wife and killed the kidnappers. Next he paid back his new allies by eliminating some of their rivals, in the process strengthening his bond with existing allies and boosting his influence and reputation among other tribes. Other men, the story goes, tired of endless clan warfare, joined him.

Temujin proclaimed Chinggis Khan

Genghis Khan formed an important alliance with Toghril, his father’s sworn brother, and became the leader of his clan (the Borjigin Mongol clan) when eight prince swore allegiance to him. In a dramatic struggle described in The Secret History of the Mongols, Temujin, by the age of twenty, had become the leader of the Kiyat subclan and by 1196, the unquestioned chief of the Borjigin Mongols.Then through a combinations of powerful alliances, marriages and a series of battles, he brought several tribes under his control and defeated the Tatars, a powerful Turkic tribe that killed his father, and effectively wiped them off the face of the earth by ordering the execution of any male taller than the height of a cart axle (everyone except young children) to ensure that the next generation would be loyal to him. There is still ambiguity as to who the Tatars actually are. Russians and Europeans later used the name Tartar to describe the Mongols (See Tatars).

It took 16 years of nearly constant warfare for Temujin to consolidate his power north of the Gobi. Much of his early success was because of his first alliance, with the neighboring Kereit clan, and because of subsidies that he and the Kereit received from the Jin emperor in payment for punitive operations against Tatars and other tribes that threatened the northern frontiers of Jin. Jin by this time had become absorbed into the Chinese cultural system and was politically weak and increasingly subject to harassment by Western Xia, the Chinese, and finally the Mongols. Later Temujin broke with the Kereit, and, in a series of major campaigns, he defeated all the Mongol and Tatar tribes in the region from the Altai Mountains to Manchuria. In time Temujin emerged as the strongest chieftain among a number of contending leaders in a confederation of clan lineages. His principal opponents in this struggle had been the Naiman Mongols, and he selected Karakorum (west-southwest of modern Ulaanbaatar, near modern Har Horin), their capital, as the seat of his new empire.*

Genghis defeated other powerful Mongol-related tribes such as the Taichutt and Naiman. As his power grew some of Temüjen’s friends turned against him. Togbril's army was crushed in a fierce three day battle and Jamuqa allied himself with the Naiman. When the Naiman were defeated, Temügen granted Jamuqa his last wish, "Let me die quickly." Scholars believe these events did happen because they are mentioned in old Chinese records.

Genghis Khan and Takes Control of the Mongols

Genghis Khan unified "all the tribes living under felt-tents" and the people under him by replacing tribal loyalties with a feudal system and organizing a well-disciplined army, a task that began in 1185 and took more than 20 years to achieve and wasn’t really completed until the priest class was under his control. According to one story Khan was able assuage the powerful Mongol priest class and claim absolute power by executing one priest for allegedly betraying the Khan's brother.

In 1206 at a great assembly of tribal leaders known as "kuriltai", gave 40-year-old Temüjen the title of Genghis Khan, which means "Strong Ruler," “Rightful Ruler,” "Oceanic Ruler," "Emperor of all Emperors" or "Perfect Warrior"---depending on which scholar you ask. Along with the title the charismatic Genghis Khan took control over all the Turk-Mongol people---a group described as “all the people who live in felt tents”---in an area of desert and steppe in Mongolia the size of Alaska

Genghis Khan's leadership of all Mongols and other peoples they had conquered between the Altai Mountains and the Da Hinggan (Greater Khingan) Range was acknowledged formally by the kuriltai. Temujin took the honorific Genghis (also romanized as genghis or jenghiz), creating the title Genghis Khan, in an effort to signify the unprecedented scope of his power. In latter hagiography, Genghis was said even to have had divine ancestry. [Source: Library of Congress]

From the tribal groups that attending his enthronement Genghis Khan forged a strong confederation of Mongol tribes, and a powerful army composed of units under fealty-swearing tribal chieftains. The Khans most loyal supporters late become his greatest generals, the most brilliant of which were Jebe and Subedal

Genghis Khan, the Military Leader

Genghis Khan's military camp

Genghis Khan conquered more territory than any other single commander in the history of the world. He was personally responsible of the conquering of present-day Mongolia, northern China and most of Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan in the space of less than 20 years. He is also credited with inventing the blitzkrieg to achieve this. Both Rommel and Patton were among the admirers of his tactics.

Although his soldiers were paid with the treasures they looted from conquered cities, Genghis Khan himself seemed less interesting in loot than conquest itself. The Persian chronicler Rashid Ad-Din, quoted him as saying: "Man's greatest good fortune is to chase and defeat his enemy, seize his total possessions, leave his married women weeping and wailing, ride his gelding, use the bodies of his women as a nightshirt and support."

Historians credit Genghis Khan’s military success to his management and organization skills. He organized his forces into groups of ten, subjected them to rigorous training, issued standized equipment and promoted officers on the basis of merit rather than blood or clan relations.

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Many believe that his unification of the Mongols — rather than the conquests that he initiated once he had unified the Mongols — was Genghis Khan's biggest accomplishment. Unifying the Mongols was no small achievement — it meant bringing together a whole series of disparate tribes. Economically the tribal unit was optimal for a pastoral-nomadic group, but Genghis brought all the tribes together into one confederation, with all its loyalty placed in himself. This was indeed a grand achievement in a country as vast as Mongolia, an area approximately four times the size of France. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols ]

“Once Genghis had succeeded in bringing the Mongols together, in 1206, a meeting of the so-called Khuriltai (an assemblage of the Mongol nobility) gave their new leader the title of "Genghis Khan": Khan of All Between the Oceans. Genghis's personal/birth name was Temujin; giving him the title "Genghis Khan" was an acknowledgment by the Mongol nobles of Genghis's leadership and their loyalty. From that point on Temujin would be the Khan of all within Mongolia and of the Mongols.”

Genghis Khan, the Military Strategist

Temujin after being proclaimed Chinggis Khan

Genghis Khan was also "a supreme military strategist and talented politician, as adept at forging alliances and gathering intelligence as he was at wreaking terror and havoc." [Source: Michael D. Lemonick, Time magazine, September 26, 1994]

Genghis Khan was crafty as well as cruel. Kessler told Time that he "was a very intelligent man and not at all compulsive. He avoided war if he could subjugate another tribe with diplomacy. “If he had to fight he would use spies to gather all the available information and then send in agents to unsettle the situation before attacking."

Genghis Khan developed complicated battle strategies and carefully chose his routes of attack. Before engaging in battle, he calculated the benefits and costs and withdrew if the costs were too high. He avoided combat himself and often hid once the battle began. After every military campaign, Genghis Khan returned to Mongolia.

Genghis Khan, the Administrator

The contributions of Genghis to Mongol organizational development had lasting impact. He took personal control of the old clan lineages, ending the tradition of noninterference by the khan. He unified the Mongol tribes through a logistical nexus involving food supplies, sheep and horse herds, intelligence and security, and transportation. A census system was developed to organize the decimal-based political jurisdictions and to recruit soldiers more easily. As the great khan, Genghis was able to consolidate his organization and to institutionalize his leadership over a Eurasian empire. Critical ingredients were his new and unprecedented military system and politico-military organization. His exceptionally flexible mounted army and the cadre of Chinese and Muslim siege-warfare experts who facilitated his conquest of cities comprised one of the most formidable instruments of warfare that the world had ever seen. [Source: Library of Congress]

In a review of Erik Hildinger’s “Warriors of the Steppe”, Christopher Berg wrote: “Genghis Khan as an astute ruler who understood the transitory lifespan of steppe regimes and had the foresight to plan against the dissolution of his hard-fought gains. In order to do this, Genghis Khan assimilated conquered peoples into the Mongol tribe. He rewarded loyalty with positions of favor and filled his army with men devoted to him. Settled populations, especially those in fortified cities, were difficult to conquer but incursions into China held the answer.

To prevent intra-tribe rivalry Genghis Khan divided Mongols tribes like the Kereyits and the Merkits into different units and gave positions of leadership to seasoned fighters not tribal chiefs. Genghis Khan also created a 10,000-man personal guard and kept hostages from powerful families to suppress the likelihood of a revolt.

Genghis Khan filled his government with foreigners. Chinese scholars were brought in to run the government and Uygurs were recruited as accountants and scribes. Some have even gone as far as to say that Genghis Khan introduced democratic forms of government to places that formally didn’t have any.

Genghis Khan spread the use of the Tasaq, or Mongol legal code, and the iqta system, which remained alive in many places that were conquered by the Mongols and adopted by other conquering people such as the Ottoman Turks that followed them. Iqta system, See Below.

Yassa: Genghis Khan's Code of Laws

Yassa was a secret written code of law created by Genghis Khan. The word Yassa translates into "order" or "decree". It was the de facto law of the Mongol Empire even though the "law" was kept secret and never made public. The Yassa seems to have its origin as decrees issued in wartime. Later, these decrees were codified and expanded to include cultural and life-style conventions. By keeping the Yassa secret, the decrees could be modified and used selectively. It is believed that the Yassa was supervised by Genghis Khan himself and his stepbrother Shihihutag who was then high judge of the Mongol Empire. Genghis Khan appointed his second son Chagatai (later Chagatai Khan) to oversee the execution of the laws. [Source: Wikipedia]

The famous historian Harold Lamb wrote: “With the selection of Genghis Khan as master of the Turko-Mongol people, these people were united for the first time in centuries. They were enthusiastic, believing that Genghis Khan was sent from the gods and endowed with the power of Heaven. They had long been governed only by tribal custom, and, to hold them in check, Genghis Khan drew from his Mongol military organization and also created a code of laws, the Yassa, which was a combination of his will and tribal customs. [Source: “Genghis Khan – Emperor of All Men,” by Harold Lamb International Collections Library, Garden City, New York, 1927, Macrohistory and World Timeline, fsmitha.com . The laws of Genghis Khan have been translated from Petis de la Croix. He was unable to get a complete list of the laws – a "Yassa Gengizcani." These 22 rulings have been taken from various sources, the Persian chroniclers, and Fras Rubruquis and Carpini. The list is incomplete and has come down to us from alien sources \^/]

The Yassa aimed at three things: obedience to Genghis Khan, a binding together of the nomad clans, and the merciless punishment of wrong-doing. It concerned itself with people, not property. Unless a man actually confessed, he was not judged guilty unless he was caught in the act of crime. Among the Mongols – who did not read – a man's spoken word was a solemn matter. \^/

The Laws of Genghis Khan: 1) It is ordered to believe that there is only one God, creator of heaven and earth, who alone gives life and death, riches and poverty as pleases Him – and who has over everything an absolute power. 2) Leaders of a religion, preachers, monks, persons who are dedicated to religious practice, the criers of mosques, physicians and those who bathe the bodies of the dead are to be freed from public charges. 3) It is forbidden under penalty of death that any one, whoever he may be, shall be proclaimed emperor unless he has been elected previously by the princes, khans, officers and other Mongol nobles in a general council. \^/

4) It is forbidden chieftains of nations and clans subject to the Mongols to hold honorary titles. 5) Forbidden to ever make peace with a monarch, a prince or a people who have not submitted. 6) The ruling that divides men of the army into tens, hundreds, thousands, and ten thousands is to be maintained. This arrangement serves to raise an army in a short time, and to form raw units of commands. 7) The moment a campaign begins, each soldier must receive his arms from the hand of the officer who has them in charge. The soldier must keep them in good order, and have them inspected by his officer before a battle. 8) Forbidden, under the death penalty, to pillage the enemy before the general commanding gives permission; but after this permission is given the soldier must have the same opportunity as the officer, and must be allowed to keep what he has carried off, provided he has paid his share to the receiver for the emperor. \^/

imagining Genghis Khan temporary palace

9) To keep the men of the army exercised, a great hunt shall be held every winter. On this account, it is forbidden any man of the empire to kill from the month of March to October, deer, bucks, roe-bucks, hares, wild ass and some birds. 10) Forbidden, to cut the throats of animals slain for food; they must be bound, the chest opened and the heart pulled out by the hand of the hunter. 11) It is permitted to eat the blood and entrails of animals – though this was forbidden before now. 12) (A list of privileges and immunities assured to the chieftains and officers of the new empire.) 13) Every man who does not go to war must work for the empire, without reward, for a certain time. \^/

14) Men guilty of the theft of a horse or steer or a thing of equal value will be punished by death and their bodies cut into two parts. For lesser thefts the punishment shall be, according to the value of the thing stolen, a number of blows of a staff – seven, seventeen, twenty-seven, up to seven hundred. But this bodily punishment may be avoided by paying nine tines the worth if the thing stolen. 15) No subject of the empire may take a Mongol for servant or slave. Every man, except in rare cases, must join the army. 16) To prevent the flight of alien slaves, it is forbidden to give them asylum, food or clothing, under pain of death. Any man who meets an escaped slave and does not bring him back to his master will be punished in the same manner. \^/

17) The law of marriage orders that every man shall purchase his wife, and that marriage between the first and second degrees of kinship is forbidden. A man may marry two sisters, or have several concubines. The women should attend to the care of property, buying and selling at their pleasure. Men should occupy themselves only with hunting and war. Children born of slaves are legitimate as the children of wives. The offspring of the first woman shall be honored above other children and shall inherit everything. \^/

18) Adultery is to be punished by death, and those guilty of it may be slain out of hand. 19) If two families wish to be united by marriage and have only young children, the marriage of these children is allowed, if one be a boy and the other a girl. If the children are dead, the marriage contract may still be drawn up. 20) It is forbidden to bathe or wash garments in running water during thunder. 21) Spies, false witnesses, all men given to infamous vices, and sorcerers are condemned to death. 22) Officers and chieftains who fail in their duty, or do not come at the summons of the Khan are to be slain, especially in remote districts. If their offense be less grave, they must come in person before the Khan. \^/

Genghis Khan’s Lifestyle

Little is known of Genghis Khan’s life. He is said to have been afraid of dogs and his passion seemed to be falconry. He kept 800 sake falcons and 800 attendants to take care of them and demanded that 50 camel-loads of swans, a favored prey, be delivered every week. His favorite wine was shiraz.

Genghis Khan is thought to have been very superstitious and a believer in spirits. He consulted shaman and astrologers. One of the most important persons in his empire was a shaman, known as Tov Tengri, who ultimately betrayed Genghis by trying to install a rival khan and was killed by having his back broken in a staged wrestling match. When Genghis Khan was an old man he ordered a 71-year-old Chinese-Taoist alchemist to mix up an elixir of immortality at his camp in the Hindu Kush.

Based on reports that his wives and mother had converted to Christianity and the fact that large numbers of Nestorian Christians practiced their religion in the Mongol empire, many Europeans thought Genghis Khan was a Christian. Some Europeans even thought he was Prester John, the great mythical savior of Christianity who lived in a land of gold and was supposed to help the Crusaders reclaim the Holy Land from the Muslims.

Genghis Khan's Death

It is said Genghis Khan died on August 18, 1227 at the age of 60 somewhere south of the Xi Xia capital of Ningxia, near present-day Yinchian in Gansu Province, during the military campaign there. According to the "Secret History" he died hunting wild ass when his mount shied and he fell, "his body being in great pain." According to another account he ailing, perhaps with typhus or malaria. From his deathbed Genghis Khan ordered the extermination of the Xi Xia people. No one knew about Genghis Khan's death until weeks later when the XI Xia were defeated.

According to the Chinese government: “There are many stories and records about his death, the place he was buried, his coffin and so on. As is told, when Genghis Khan fought against Western Xia dynasty, he had passed Yijinhuoluo. He stopped his horse, looked around, and was reluctant to leave this beautiful grassland with lush grass, flowers and flocks. Just at that time, the horsewhip dropped from his hand, and he seemed to realize something, and chanted: "a place where flowers and deer inhabits, a home where hoopoes give birth to their babies, a terra where the declined dynasty revives, and a garden where gray-haired man enjoys his life." And he told his servants: "after I died, bury me here."” [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, kepu.net.cn]

Genghis Khan Mausoleum

Morris Rossabi wrote in Natural History: “In August 1227, a somber funeral procession — escorting the body of perhaps the most renowned conqueror in world history — made its way toward the Burkhan Khaldun (Buddha Cliff) in northeastern Mongolia. Commanding a military force that never amounted to more than 200,000 troops, this Mongol ruler had united the disparate, nomadic Mongol tribes and initiated the conquest of territory stretching from Korea to Hungary and from Russia to modern Vietnam and Syria. His title was Genghis Khan, “Khan of All Between the Oceans.” [Source: “All the Khan’s Horses” by Morris Rossabi, Natural History, October 1994]

The funeral procession from China to Mongolia took several weeks to arrive. According to Marco Polo, who arrived in Mongolia about 60 years later, soldiers accompanying the procession killed everyone they encountered, as well as some 2,000 servants, 40 horses and 40 "moonlike virgins" who were allegedly buried with the Khan to keep him company in the next world. To discourage grave robbers the site was reportedly trampled by a thousand horsemen, who along with the soldiers who accompanied the procession were all executed to keep the location of his tomb secret.

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: There is another "possibility, however, that Genghis's body was simply allowed to lie were it fell. At this time in their history, the Mongols had not yet developed a tomb culture; in fact, they would only develop a tomb culture after they'd had greater contact with the Chinese and the Persians. Thus, Genghis's body may have been left to be consumed by the animals." [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols ]

See Separate Article DEATH OF GENGHIS KHAN AND THE SEARCH FOR HIS TOMB factsanddetails.com

Genghis Khan’s Four Legacies

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Tolerance: One of Genghis Khan's greatest legacies was the principle of religious tolerance. In general, Genghis provided tax relief to Buddhist monasteries and to a variety of other religious institutions. And though Genghis himself never converted to any of the religions of the sedentary peoples he conquered (he remained loyal to Mongolian shamanism), he was quite interested in Daoism, particularly because of the Daoists' pledge that they could prolong life. In fact, on his expedition to Central Asia Genghis was accompanied by Changchun, a Daoist sage from China, who kept an account of his travels with his Mongol patron. Changchun's first-hand account has become one of the major primary sources on Genghis Khan and the Mongols. [Also see The Mongols in China: Religious Life under Mongol Rule]

“Written Language: “The creation of the first Mongol written language was another legacy of Genghis Khan. In 1204, even before he gained the title of "Genghis Khan," Genghis assigned one of his Uyghur retainers to develop a written language for the Mongols based upon the Uyghur script. [Also see The Mongols in China: Cultural Life under Mongol Rule, to compare Genghis's legacy to Kublai Khan's commissioning of a Mongol script.]

Nine nukers of Genghis Khan

“Trade and Crafts: “A third legacy was Genghis's support for both trade and crafts, which meant support for the merchants and artisans in the business of trade and craft. Genghis recognized early on the importance of trade and crafts for the economic survival of the Mongols and actively supported both.

“Legal Code: Genghis also left behind a legal code, the so-called Jasagh, which consisted of a series of general moral injunctions and laws. The Jasagh also prescribed punishments for transgressions of laws relating particularly to pastoral-nomadic society.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons Text Sources: Mike Edwards, National Geographic: Genghis Khan: December, 1996; After Genghis Khan: February 1997; National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, Comptom’s Encyclopedia, Lonely Planet Guides, Silk Road Foundation and various books and other publications.

Last updated February 2019