MONGOL RULE

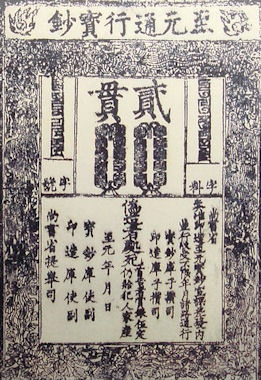

Yuan (Mongol) paper money

As was true with the horse clans that preceded them, the Mongols were good conquerors but not very good government administrators. After Genghis died and his kingdom was divided up among his four sons and one of his wives and endured in that state for one generation before it was divided further among Genghis's grandchildren. At this stage the empire began to fall apart. By the time Kublai Khan gained control of a large portion of eastern Asia, the Mongol control of "heartland" in Central Asia was disintegrating.

Still the Mongols were able rulers and administrators and parts of the realm endured for hundreds of years. Although tte Mongols were traditionally nomadic animals herders but they proved to be quite adaptable to foreign influences and pragmatic. They promulgated the Yasa (Jasagh), or imperial code, which laid out the organizational lines of the Mongol nation, the administration of the army, and criminal, commercial, and civil codes of law. As administrators the Mongols employed many Uygurs and the khans married Christians and members of the religions. Under Genghis Khan the Mongols adopted the Uyghur writing, an alphabetic system written in vertical lines from left to right, which has survived to this day and was picked up other ethnic groups. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed.]

Stefano Carboni and Qamar Adamjee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The Mongols were remarkably quick in transforming themselves from a purely nomadic tribal people into rulers of cities and states and in learning how to administer their vast empire. They readily adopted the system of administration of the conquered states, placing a handful of Mongols in the top positions but allowing former local officials to run everyday affairs. This clever system allowed them to control each city and province but also to be in touch with the population through their administrators.[Source: Stefano Carboni and Qamar Adamjee, Department of Islamic Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art \^/]

“The seat of the Great Khanate in Dadu (Beijing) was the center of the empire, with all its pomp and ceremony, whereas the three semi-independent Central and western Asian domains of the Chaghatay, the Golden Horde, and the Ilkhanids were connected through an intricate network that crisscrossed the continent. Horses, once a reliable instrument of war and conquest, now made swift communication possible, carrying written messages through a relay system of stations. A letter sent by the emperor in Beijing and carried by an envoy wearing his paiza, or passport, could reach the Ilkhanid capital Tabriz, some 5,000 miles away, in about a month.’ \^/

See Separate Article WILLIAM OF RUBRUCK ON MONGKE KHAN factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Mongols and Horsemen of the Steppe: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; The Mongol Empire web.archive.org/web ; The Mongols in World History afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols ; William of Rubruck's Account of the Mongols washington.edu/silkroad/texts ; Mongol invasion of Rus (pictures) web.archive.org/web ; Encyclopædia Britannica article britannica.com ; Mongol Archives historyonthenet.com ; “The Horse, the Wheel and Language, How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes shaped the Modern World", David W Anthony, 2007 archive.org/details/horsewheelandlanguage ; The Scythians - Silk Road Foundation silkroadfoundation.org ; Scythians iranicaonline.org ; Encyclopaedia Britannica article on the Huns britannica.com ; Wikipedia article on Eurasian nomads Wikipedia

Khans

The Khans were the leaders of the Mongols. They included Genghis Khan, his sons and his grandsons—Batu Khan, Magu Khan, Kublai Khan, and Hulag.

"The Mongol Khans," wrote historian Daniel Boorstin, "were as able a dynasty as ever ruled a great empire. They showed a combination of military genius, personal courage, administrative versatility, and cultural tolerance unequaled by any European line of hereditary rulers. They deserve a higher place and a different place than they have been given by the Western historian." [Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin]

When a Mongol army was on the move, the great khan's tumen was usually far behind the main strike forces and the golden-cloaked khan usually rode on horseback beside the golden ger. Lance-bearing khan guardsmen rode at the front of the tumen. Next to the golden ger flew the khan’s banner —a grey wolf, representing the son of the blue sky, on a gold background—and a standard that carried white horsetails if the Mongols were at peace and black tails if they were at war.

The royal entourage consisted of guards, family members, generals, servants and trusted advisors. The khan's falconer held a particularly high position.

Mongol Administration

plate to make Yuan (Mongol) paper money

After a region was conquered, power was handed over to trusted subordinates. Genghis Khan insisted that booty be centrally collected and equally distributed. Local officials and clerks were often spared as they could help run the city. Records were kept and written communications were conducted in an Uyghur script that was adopted by many Turkic-speaking peoples.

According to the Encyclopaedia Judaica: “The situation of the Jews in the Islamic countries conquered and ruled by the Mongols appears to have dramatically improved. Jews, as well as Christians, enjoyed relative religious freedom and the restrictive laws derived from the so-called Covenant of Omar were abolished for several decades. The activity of the free-thinking Jewish philosopher and scholar of comparative religion Ibn Kammūna (d. 1285) in Baghdad can be attributed to some degree to the relatively tolerant atmosphere in the realm of religion introduced by the Mongols. [Source: Encyclopaedia Judaica]

The Mongols set up a good transportation and communications network that reached to all corners of their empire. They set up guards and post stations at regular intervals and sent messages using a kind of pony express that could cover almost 200 miles a day. The riders wore bells to warn people to get out their way. Often a single rider traveled with two horses, switching between, often without touching the ground, while the horses surged ahead at full speed. All male herdsmen were required to spend some time working in the system, which continued in operation until 1949.

The Mongols also developed a famine relief scheme, and expanded the expanded the canal system in China which helped to bring grain to the cities. The streets of the cities under control were relatively safe, goods moved relatively unhindered through the kingdom. The achievements of the Mongols and Kublai Khan were described in Marco Polo's "Description of the World".

Economy of the Mongols

Historically, the Mongols supplement their economy with trade and raiding. They never really developed a merchant class. The most common trade involved exchanges of animals, fur and hides for grain, tea, silk, cloth and manufactured products from China and Russia. Until the 7th century and the establishment of Buddhist estates “property” was defined only as movable property. [Source: William Jankowiak, Ian Skoggard, and John Beierle, e Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF) World Cultures, Yale University]

Naadams have traditionally been a time and place where a great deal of business and trade was conducted. The modern Naadam is a multiday-day festival featuring the traditional Mongolian sports of horse racing, archery and wrestling. Nadaam (meaning "to play" or "have a good time") is the biggest holiday of the year. Usually held in mid July, it is a time when nomads have traditionally gathered at designated places in the country to enjoy long summer days, catch up on news with old friends and enjoy sports and other events. The biggest Nadaam takes place 50 kilometers or so from Ulan Baatar.

Land has traditionally not belonged to individuals but to tribes and clans of herders. Each tribe or clan had its regular grazing grounds and families were allotted space within this scheme. There were — and still are — almost no fences. With horse people and nomads, wealth has traditionally rested with their animals not in land. The value of land was measured by its ability to provide water and pastures for animals.

Iqta System and Taxes

Mongols hunting

The "iqta" system, in which land was divided up into non-hereditary fiefs, was introduced by the Mongols an endured in dynasties after the Mongols. These fiefs were governed by a sultan or a lord known as pasha who was selected for various reasons including distinguishing oneself in war or by giving gifts or providing women for the Khan’s harem.

Compared to feudalism, the disadvantage of the iqta was that pashas were encouraged to get rich quick and hoard their loot since their land would not necessarily end up in the hands of their descendants. This lead to the overtaxation of subjects, "skimping" on military obligations, and negligence. The advantage is that land was granted by some degree by merit and intrigues and wars between pashas was minimized.

The Mongols supported their empire with taxes collected taxes from the cities and kingdoms that came under their power. According to historian Thomas Allen at Trenton State College the Mongols imposed a variety of taxes. In China, there was a head tax paid by every adult male in grain and a household tax paid in silk. Chinese farmers were taxed according to the quality of their land and the number of oxen they owned. Similar taxes were levied throughout the empire.

Merchants were taxed based on their transactions; special levies of flour or rice were imposed to feed the armies in times of war; newly conquered people were expected to turn over a tenth of their possessions. According to Mongol law, merchants or trader that went bankrupt for a third time were given the death penalty.

One of the reason why the Mongols were not as powerful after Genghis died was that local Mongol rules started to tax local people and these leaders kept the booty for themselves instead of sharing it equally.

How Such Small Group Succeeded

How did such a small group succeed? According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “One answer to this question is that the Mongols were adept at incorporating the groups they conquered into their empire. As they defeated other peoples, they incorporated some of the more loyal subjugated people into their military forces. This was especially true of the Turks. The Uyghur Turks, along with others, joined the Mongol armies and were instrumental in the Mongols' successes. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols ]

“A second explanation is that the rest of Asia was declining at this point. China at this time was not a unified country — in fact, it was divided into at least three different sections, all of which were at war with one another. Central Asia was fragmented, and there was no single leader there. As for Russia, it was only a series of fragmented city-states. And after four centuries of success, the Abbasid dynasty in Western Asia had by this time lost much of its land.

“By 1241, Mongol troops had reached all the way to Hungary but had to withdraw that very year because of the death of Ögödei, the Great Khan. The Mongol elite returned to Mongolia to select a new Great Khan, but they were unsuccessful in their efforts to form a consensus on the matter. For the next 19 years, there would be a variety of disputes over who was the most meritorious of Genghis Khan's descendants and who ought to be the next Great Khan.”

Yassa: Genghis Khan's Code of Laws

Yassa was a secret written code of law created by Genghis Khan. The word Yassa translates into "order" or "decree". It was the de facto law of the Mongol Empire even though the "law" was kept secret and never made public. The Yassa seems to have its origin as decrees issued in wartime. Later, these decrees were codified and expanded to include cultural and life-style conventions. By keeping the Yassa secret, the decrees could be modified and used selectively. It is believed that the Yassa was supervised by Genghis Khan himself and his stepbrother Shihihutag who was then high judge of the Mongol Empire. Genghis Khan appointed his second son Chagatai (later Chagatai Khan) to oversee the execution of the laws. [Source: Wikipedia]

The famous historian Harold Lamb wrote: “With the selection of Genghis Khan as master of the Turko-Mongol people, these people were united for the first time in centuries. They were enthusiastic, believing that Genghis Khan was sent from the gods and endowed with the power of Heaven. They had long been governed only by tribal custom, and, to hold them in check, Genghis Khan drew from his Mongol military organization and also created a code of laws, the Yassa, which was a combination of his will and tribal customs. [Source: “Genghis Khan – Emperor of All Men,” by Harold Lamb International Collections Library, Garden City, New York, 1927, Macrohistory and World Timeline, fsmitha.com . The laws of Genghis Khan have been translated from Petis de la Croix. He was unable to get a complete list of the laws – a "Yassa Gengizcani." These 22 rulings have been taken from various sources, the Persian chroniclers, and Fras Rubruquis and Carpini. The list is incomplete and has come down to us from alien sources \^/]

The Yassa aimed at three things: obedience to Genghis Khan, a binding together of the nomad clans, and the merciless punishment of wrong-doing. It concerned itself with people, not property. Unless a man actually confessed, he was not judged guilty unless he was caught in the act of crime. Among the Mongols – who did not read – a man's spoken word was a solemn matter. \^/

The Laws of Genghis Khan: 1) It is ordered to believe that there is only one God, creator of heaven and earth, who alone gives life and death, riches and poverty as pleases Him – and who has over everything an absolute power. 2) Leaders of a religion, preachers, monks, persons who are dedicated to religious practice, the criers of mosques, physicians and those who bathe the bodies of the dead are to be freed from public charges. 3) It is forbidden under penalty of death that any one, whoever he may be, shall be proclaimed emperor unless he has been elected previously by the princes, khans, officers and other Mongol nobles in a general council. \^/

4) It is forbidden chieftains of nations and clans subject to the Mongols to hold honorary titles. 5) Forbidden to ever make peace with a monarch, a prince or a people who have not submitted. 6) The ruling that divides men of the army into tens, hundreds, thousands, and ten thousands is to be maintained. This arrangement serves to raise an army in a short time, and to form raw units of commands. 7) The moment a campaign begins, each soldier must receive his arms from the hand of the officer who has them in charge. The soldier must keep them in good order, and have them inspected by his officer before a battle. 8) Forbidden, under the death penalty, to pillage the enemy before the general commanding gives permission; but after this permission is given the soldier must have the same opportunity as the officer, and must be allowed to keep what he has carried off, provided he has paid his share to the receiver for the emperor. \^/

Güyük Khan with his interrogeant Djamâl al-Dîn Mahmûd Hudjandî

9) To keep the men of the army exercised, a great hunt shall be held every winter. On this account, it is forbidden any man of the empire to kill from the month of March to October, deer, bucks, roe-bucks, hares, wild ass and some birds. 10) Forbidden, to cut the throats of animals slain for food; they must be bound, the chest opened and the heart pulled out by the hand of the hunter. 11) It is permitted to eat the blood and entrails of animals – though this was forbidden before now. 12) (A list of privileges and immunities assured to the chieftains and officers of the new empire.) 13) Every man who does not go to war must work for the empire, without reward, for a certain time. \^/

14) Men guilty of the theft of a horse or steer or a thing of equal value will be punished by death and their bodies cut into two parts. For lesser thefts the punishment shall be, according to the value of the thing stolen, a number of blows of a staff – seven, seventeen, twenty-seven, up to seven hundred. But this bodily punishment may be avoided by paying nine tines the worth if the thing stolen. 15) No subject of the empire may take a Mongol for servant or slave. Every man, except in rare cases, must join the army. 16) To prevent the flight of alien slaves, it is forbidden to give them asylum, food or clothing, under pain of death. Any man who meets an escaped slave and does not bring him back to his master will be punished in the same manner. \^/

17) The law of marriage orders that every man shall purchase his wife, and that marriage between the first and second degrees of kinship is forbidden. A man may marry two sisters, or have several concubines. The women should attend to the care of property, buying and selling at their pleasure. Men should occupy themselves only with hunting and war. Children born of slaves are legitimate as the children of wives. The offspring of the first woman shall be honored above other children and shall inherit everything. \^/

18) Adultery is to be punished by death, and those guilty of it may be slain out of hand. 19) If two families wish to be united by marriage and have only young children, the marriage of these children is allowed, if one be a boy and the other a girl. If the children are dead, the marriage contract may still be drawn up. 20) It is forbidden to bathe or wash garments in running water during thunder. 21) Spies, false witnesses, all men given to infamous vices, and sorcerers are condemned to death. 22) Officers and chieftains who fail in their duty, or do not come at the summons of the Khan are to be slain, especially in remote districts. If their offense be less grave, they must come in person before the Khan. \^/

Mongol Trade and the Silk Road

Sogdian Silk Road trader

For a relatively brief period between 1250 and 1350 the Silk Road trade routes were opened up to European when the land occupied by the Turks was taken over by the Mongols who allowed free trade. Instead of waiting for goods at the Mediterranean ports, European travelers were able to travel on their own to India and China for the first time.

The Mongols were strong supporters of free trade. They lowered tolls and taxes; protected caravans by guarding roads against bandits; promoted trade with Europe; improved the road system between China and Russia and throughout Central Asia; and expanded the canal system in China, which facilitated the transportation of grain from southern to northern China

Silk Road trade flourished and trade between east and west increased under Mongol rule. The Mongol conquest of Russia opened the road to China for Europeans. The roads through Egypt were controlled by Muslim and prohibited to Christians. Goods passing from India to Egypt along the Silk Road were so heavily taxed, they tripled in price. After the Mongols were gone. the Silk Road was shut down.

Merchants from Venice, Genoa and Pisa got rich by selling oriental spices and products picked up in the Levant ports in the eastern Mediterranean. But it was Arabs, Turks and other Muslims who profited most from the Silk Road trade. They controlled the land and the trade routes between Europe and China so completely that historian Daniel Boorstin described it as the "Iron Curtain of the Middle Ages."

Mongol Paper Money and Silk Road Trade

The Mongols were the first people to use paper money as their sole form of currency. A piece of paper money used under Kublai Khan was about the size of a sheet of typing paper and had a furry felt-like feel. It was made from the inner bar of mulberry trees and according to Marco Polo was "sealed with the seal of the Great Lord."

Paper money was first produced in China in 11th century when there was a metal shortage and the government didn’t have enough gold, silver and copper to meet the demand for money. It wasn’t long before the Chinese government was producing paper currency at a rate of four million sheets a year. By the 12th century paper money was used to finance a defense against the Mongols. Notes produced in 1209 that promised a pay holders with gold and silver were printed on perfumed paper made of silk. [Source: "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin]

A piece of paper money used under Kublai Khan in the 13th century was about the size of a sheet of typing paper and had a furry felt-like feel. It were made from the inner bark of mulberry trees and according to Marco Polo was "sealed with the seal of the Great Lord." The world's largest paper money was a 1 guan note issued by the Ming dynasty of 1368-99 that was 9 by 13-inches

A piece of paper money used under Kublai Khan in the 13th century was about the size of a sheet of typing paper and had a furry felt-like feel. It were made from the inner bark of mulberry trees and according to Marco Polo was "sealed with the seal of the Great Lord." The world's largest paper money was a 1 guan note issued by the Ming dynasty of 1368-99 that was 9 by 13-inches

"Of this money,” Marco Polo wrote, “the Khan has such a quantity made that with it he could buy all the treasure in the world. With this currency he orders all payments to be made throughout every province and kingdom and region of his empire. And no one dares refuse it on pain of losing his life...I assure you, that all the peoples and populations who are subject to his rule are perfectly willing to accept these papers in payment, since wherever they go they pay in the same currency, whether for goods or for pearls or precious stones or gold or silver. With these pieces of paper they can buy anything and pay for anything...When these papers have been so long in circulation that they are growing torn and frayed, they are brought to the mint and changed from new and fresh ones at a discount of 3 per cent."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, Comptom’s Encyclopedia, Lonely Planet Guides, Silk Road Foundation, "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin; "History of Arab People" by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991) and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2022