STEPPE HORSEMAN LIFE

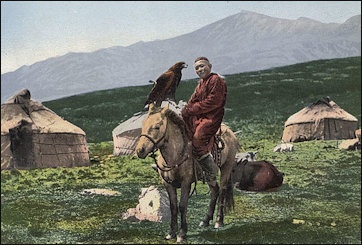

Kazakh man with a horse and golden eagle

The steppes where groups like the Huns, Avars, Magyars, Turks, Tartars and Mongols originated and evolved were harsh places that were very cold in the winter, with some of the world's lowest temperatures, and sometimes very hot in the summer, providing little more than grazing land for milk and meat producing cattle and sheep.

The steppe created a strong people. Winters were often colder than those in Alaska, and many people went hungry because there was no stored grain. Clashes between tribes erupted over the scarce resources.

The horseman of Central Asia life a lifestyle that is somewhat similar to the lifestyle of the Bedouins in the Middle East except that the horseman deal with colder temperatures but have more rain and grazing land than Bedouins.

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: ““The reproduction of sheep and goats is essential for the survival of Steppe horseman pastoralism. The animals are culled annually for food, hide, and skin, and many do not survive the harsh winters. Replenishment of the herds and flocks, therefore, is vital. But encouraging successful procreation and survival of the young requires tremendous skill and knowledge. Another threat to the survival of the sheep and goats are wolves. They generally attacked the young but were also known to threaten adult animals. Herders kept and trained fierce dogs to protect the herds from such predators. In addition, the Steppe horsemen periodically went on hunts to cull the wolf population.” [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols ]

See Separate Articles: NOMAD LIFE factsanddetails.com ; NOMAD MIGRATIONS factsanddetails.com ; NOMADS IN THE MODERN WORLD factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Mongols and Horsemen of the Steppe: "The Horse, the Wheel and Language, How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes shaped the Modern World", David W Anthony, 2007 archive.org/details/horsewheelandlanguage ; The Scythians - Silk Road Foundation silkroadfoundation.org ; Scythians iranicaonline.org ; Encyclopaedia Britannica article on the Huns britannica.com ; Wikipedia article on Eurasian nomads Wikipedia Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; The Mongol Empire web.archive.org/web ; The Mongols in World History afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols ; William of Rubruck's Account of the Mongols washington.edu/silkroad/texts ; Mongol invasion of Rus (pictures) web.archive.org/web ; Encyclopædia Britannica article britannica.com ; Mongol Archives historyonthenet.com

Steppe

The famous steppe of Central Asia is 3000-mile-long, flat or gently rolling grassland, averaging 500 miles in width. It is mostly treeless except for areas along riverbanks. It's name is derived from “stepi”, "meaning plain.

dry steppe and mountains

The Central Asian steppe stretches from Mongolia and the Great Wall of China in the east to Hungary and the Danube River in the west. It is bounded by the taiga forest of Russia to the north and by desert and mountains to the south. It is located at about same latitude as the American plains and embraces a dozen countries, including Russia, China, Mongolia, Kazakhstan, Kyrzgzstan and several other former Soviet Republics.

Describing the steppes, Polish Nobel laureate Henry Sienkiewicz wrote in "With Fire and Sword", "The steppes are wholly desolate and unpeopled yet filled living menace. Silent and still yet seething with hidden violence, peaceful in their immensity yet infinitely dangerous, these boundless spaces were a masterless, untamed country created foe ruthless men who acknowledge no one as their overlord."

The poor yellow steppe soil is much less fertile than rich black earth found in southern Russia and Ukraine. When the topsoil is stripped of vegetation it becomes dusty and is easily blown away in the wind.

Steppe Plants and Grasses

Steppes are covered mostly by sparse grass or grasses and shrubs such as saxual. Trees are often stunted. Large trunks, branches and leaves require a lot of water to maintain. When the steppes meet the foot foothills, you can find wild poppies, even wild opium poppies.

The grass family is one of the largest in the plant kingdom, embracing some 10,000 different species worldwide. Contrary to what you might think, grasses are fairly complex plants. What you see are only their leaves.

Przewalski's Horse eating steppe grasses

Grass flowers are often not recognizable as such. Because grasses rely on the breeze to distribute pollen (there is a usually lots of wind on the steppe) and they don’t need colorful flowers to attract pollinators such as birds and bees. Grass flowers have scales instead of pedals and grow in clusters on special tall stems that lift them high enough to be carried by the wind.

Grasses need lots of sunlight. They do not grow well in forests or other shady areas. Tall feather grass grows well in the well-watered parts of the steppe. Shorter grass grows better in the dry steppe where there is less rainfall. Chiy, a grass with cane-like reeds, is used by nomads to make decorative screens in the yurts

Grasses can tolerate lack of rain, intense sunlight, strong winds, shredding from lawnmowers, the cleats of Athletes and the hooves of grazing animals. They can survive fires: only their leaves burn; the root stocks are rarely damaged.

The ability of grass to endure such harsh conditions lies in the structures of its leaves, The leaves of other plants spring from buds and have a developed a network of veins that carry sap and expand into the leaf. If a leaf is damaged a plant can seal its veins with sap but do little else. Grass leaves on the other hand don't have a network of veins, rather they have unbranched veins that grow straight, and can tolerate being cut, broken or damaged, and keep growing.

Steppe Horseman Life and Culture

The Mongols reportedly never bathed. "They smell so heavily that one cannot approach them," a Chinese traveler to Mongolia reported. "They wash themselves in urine."

Steppe horsemen used to gather at fairs, which some scholars claim may have been the first slave markets. Some scholars claim that horsemen introduced slavery to Asia. There was no evidence of slavery in China until the arrival of the Shang charioteers. In India the caste system grew out of the enslavement of people from the Indus Valley by the Aryans.

Mongol art had to be light enough to carry around on horseback. Soldiers from the steppe wore bronze chest plates engraved with attacking leopards with huge claws, birds with the ears of a wolf and the beak of an eagle, hawks grabbing bear cubs, tigers leaping on antelope, and dragons.

Steppe horsemen didn't engage in sports the way the Greeks did. Displays of prowess by champions and divinations was sometimes held before battle.

Steppe Horseman and Horses

milking a horse

Steppe horsemen usually traveled with strings of horses. This was necessary because the horse that carried the rider did much more work than the other horses. When it tired the rider could change to fresh horse. A single rider Marco Polo noted might have 18 mounts, which meant that the horseman had to camp in places with a large amount of grazing land.

Steppe horsemen rode in all season, seemingly impervious to extreme weather. When the Russians retired for the winter, the Mongols kept on riding and recruited peasants for their hordes. They often waited to winter, when the rivers froze and they could go almost anywhere, to stage their attacks, which in turn surprised their enemies. Horsemen sometimes sang love songs to their mounts.

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Horses offered mobility to the Steppe horsemen, permitting them to roam the steppes in search of pasture for their flocks, as well as to round up other horses that have been allowed to graze freely faraway from an encampment. Riders gathering the horses together were equipped with a pole at the end of which was a special lasso. Children, who became skilled riders at an early age, assumed this responsibility on occasion. In traditional times horses gave the Steppe horsemen the decided tactical advantage of mobility in conflicts against sedentary civilizations. They could, for example, initiate a hit-and-run raid on a Chinese village, fleeing to the steppelands and thus evading the less mobile Chinese forces. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols ]

“In summer, women milked the mares, sometimes as often as eight or nine times daily. Much of the milk was allowed to ferment, producing an alcoholic drink known as airag (or koumiss). Some of the Mongol Khans and members of the elite consumed vast quantities of liquor, including airag, prompting one scholar to attribute the fall of the Mongol Empire in part to the increasing problem of alcoholism among its leaders.

See Food

Steppe Horseman and Language

In a review of “The Horse, the Wheel, and Language” by David W. Anthony, Christine Kenneally wrote in New York Times, “Linguistic inheritance is a story of irreducible patterns and historical contingencies... Anthony argues that we speak English not just because our parents taught it to us but because wild horses used to roam the steppes of central Eurasia, because steppe-dwellers invented the spoked wheel and because poetry once had real power. [Source: Christine Kenneally, New York Times, March 2, 2008 ^*^]

“English belongs to the very large Indo-European language family. All of the Germanic, Baltic, Slavic, Celtic, Latin, Hellenic, Iranian and Sanskrit languages (among other families) are Indo-European, which means that Lithuanian, Polish, English, Welsh, French, Greek, Kurdish and Punjabi, to name just a few, descend from the same ancient tongue. It is known as Proto-Indo-European, and it was spoken around 3500 B.C. Thanks to a careful comparison of the daughter languages (as linguists call them), thousands of Proto-Indo-European words have been reconstructed, including those for otter, wolf, lynx, bee, honey, cattle, sheep and horse. The way some words group together in Proto-Indo-European shows that its speakers believed in a male sky god, respected chiefs and appointed official warriors. One word for wheel sounded something like “roteh.” The word for axle? “Aks.” ^*^

“Where Proto-Indo-European came from and who originally spoke it has been a mystery ever since Sir William Jones, a British judge and scholar in India, posited its existence in the late 18th century. As a result, Anthony writes, the question of its origins was “politicized almost from the beginning.” Numerous groups, ranging from the Nazis to adherents of the “goddess movement” (who saw the Indo-Europeans as bellicose invaders who upended a feminine utopia), have made self-interested claims about the Indo-European past. Anthony, an archaeologist at Hartwick College who has extensive field experience, makes the persuasive case that it originated in the steppes of what is now southern Ukraine and Russia, a landscape consisting mainly of endless grasslands and “huge, dramatic” sky. Anthony is not the first scholar to make the case that Proto-Indo-European came from this region, but given the immense array of evidence he presents, he may be the last one who has to. ^*^

“Anthony lays out crucial events that built up the economic and, later, military power of Proto-Indo-European speakers, increasing the reach and prestige of the language. It’s a linguistic version of the rich getting richer, with the result that more than three billion people around the world today speak a descendant of this mother tongue. Perhaps the most important moment came with the domestication of horses, first accomplished around 4,800 years ago, at least 2,000 years after cattle, sheep, pigs and goats had been domesticated in other parts of the world. Initially, horses were most likely tamed to serve as an easy source of meat, particularly in winter; it wasn’t until centuries later that they were ridden, and then eventually used to pull carts with solid wheels, turning the Proto- Indo-European speakers into mobile herders and the steppes into a conduit for themselves and their language. Later, they became skilled warriors whose spoked-wheel chariots sped them to battle and spread their language even farther. ^*^

“The impact of horses on the reach of language is particularly important to Anthony, and he conveys his excitement at working out whether ancient horses wore bits (and were therefore ridden by Proto-Indo-Europeans) by comparing their teeth to those of modern domesticated and wild horses. He muses on the “deep-rooted, intransigent traditions of opposition” that existed along the Ural River frontier, slowing the spread of herding and the cultural innovations that went with it. He also cites remarkable genetic analyses suggesting that although all the domesticated horses in the world may have come from many different wild mothers, they might all share a single father. ^*^

“Anthony also describes a world in which spoken poetry was the only medium, one that helped spread Proto-Indo-European through what he calls “elite recruitment.” It wasn’t enough for the newcomers to assume a dominant position: in order for their language to be picked up, they also had to offer the local population attractive opportunities to participate in their language culture — a process that continues today, incidentally, with the spread of English as a prestige language. “The Horse, the Wheel, and Language” brings together the work of historical linguists and archaeologists, researchers who have traditionally been suspicious of one another’s methods. Though parts of the book will be penetrable only by scholars, it lays out in intricate detail the complicated genealogy of history’s most successful language.

Book: “The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders From the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World” by David W. Anthony ( Princeton University Press, 2008)

First Pants Worn by 3,000-Year-Old Central Asian Horsemen

The oldest known trousers — a roughly 3,000-year-old pair with woven leg decorations — was found in the tomb of Central Asian horsemen in western China. Bruce Bower wrote in Science News, “Two men whose remains were recently excavated from tombs in western China put their pants on one leg at a time, just like the rest of us. But these nomadic herders did so between 3,300 and 3,000 years ago, making their trousers the oldest known examples of this innovative apparel, a new study finds.[Source: Bruce Bower, Science News, May 30, 2014 -]

“With straight-fitting legs and a wide crotch, the ancient wool trousers resemble modern riding pants, says a team led by archaeologists Ulrike Beck and Mayke Wagner of the German Archaeological Institute in Berlin. The discoveries, uncovered in the Yanghai graveyard in China’s Tarim Basin, support previous work suggesting that nomadic herders in Central Asia invented pants to provide bodily protection and freedom of movement for horseback journeys and mounted warfare, the scientists report May 22 in Quaternary International. “This new paper definitely supports the idea that trousers were invented for horse riding by mobile pastoralists, and that trousers were brought to the Tarim Basin by horse-riding peoples,” remarks linguist and China authority Victor Mair of the University of Pennsylvania. Previously, Europeans and Asians wore gowns, robes, tunics, togas or — as observed on the 5,300-year-old body of Ötzi the Iceman — a three-piece combination of loincloth and individual leggings. -

world's oldest pants

“A dry climate and hot summers helped preserve human corpses, clothing and other organic material in the Tarim Basin. More than 500 tombs have been excavated in a graveyard there since the early 1970s. Earlier research on mummies from several Tarim Basin sites, led by Mair, identified a 2,600-year-old individual known as Cherchen Man who wore burgundy trousers probably made of wool. Trousers of Scythian nomads from West Asia date to roughly 2,500 years ago. -

“Mair suspects that horse riding began about 3,400 years ago and trouser-making came shortly thereafter in wetter regions to the north and west of the Tarim Basin. Ancient trousers from those areas are not likely to have been preserved, Mair says. Horse riding’s origins are uncertain and could date to at least 4,000 years ago, comments archaeologist Margarita Gleba of University College London. If so, she says, “I would not be surprised if trousers appeared at least that far back.”-

“The two trouser-wearing men entombed at Yanghai were roughly 40 years old and had probably been warriors as well as herders, the investigators say. One man was buried with a decorated leather bridle, a wooden horse bit, a battle-ax and a leather bracer for arm protection. Among objects placed with the other body were a whip, a decorated horse tail, a bow sheath and a bow. Beck and Wagner’s group obtained radiocarbon ages of fibers from both men’s trousers, and of three other items in one of the tombs. -

“Each pair of trousers was sewn together from three pieces of brown-colored wool cloth, one piece for each leg and an insert for the crotch. The tailoring involved no cutting: Pant sections were shaped on a loom in the final size. Finished pants included side slits, strings for fastening at the waist and woven designs on the legs. Beck and Wagner’s team calls the ancient invention of trousers “a ground-breaking achievement in the history of cloth making.” That’s not too shabby for herders who probably thought the Gap was just a place to ride their horses through.” -

Steppe Horsemen Food and Drink

The steppe horseman diet consisted almost exclusively of meat and dairy products from the animals they took with them. Mostly they ate mutton and milk from the sheep they herded. They only slaughtered horses in emergencies or special occasions. Horsemen on the move only ate horses when they died. At weddings and large feasts horsemen slaughtered fat mares and served horse heads and horsemeat sausages to honored guests. They relied on horses for food in the summer months when ewes and cows stopped giving milk.

Steppe nomads on the move, ate and drank when they could, and often subsisting for weeks at a time on nothing but horse blood and mare's milk. Marco Polo wrote a Mongol horseman could sustain himself by drinking his mount's blood and "ride quite ten days' march with eating cooked food and without lighting a fire."

Some steppe horsemen ate meat raw but tenderized by placing it under their saddle during long rides. Friction warmed the meat and the sweat seasoned it.

Describing the eating and drinking habits of nomads on a 1,700 mile journey across China in the 1920s, American anthropologist Owen Lattimore wrote: "We began at dawn by making tea...of the coarsest grade of twigs, leaves and tea sweepings...In this tea we used to mix either roasted oaten flour or roasted millet---looking like canary seed....About noon we had the one real feed of the day. This would be made of half-cooked dough."

"The reason we drank so much tea was because of the bad water. Water alone, unboiled, is never drunk...Our water everywhere was from wells, all of them more or less heavily tainted with salt, soda...At times it was almost too salty to drink, at other times very bitter. The worst water...is thick, almost sticky and incredibly bitter and nasty." [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

See Separate Article KOUMISS (AIRAG) factsanddetails.com

Steppe Horseman Livestock and Agriculture

vegetables that are grown in Mongolia

Steppe horsemen kept horses, sheep and cattle and traveled with the seasons looking for grazing land for their animals. Generally they moved to low pastures and southern areas in winter and to high pastures and northern areas in the summer.

The early clans most likely had claims to certain grazing areas. Even after they created large empires the Turks and Mongols didn't like being settled in one place. They looked down on farmers as sissies, and even though life on the steppe was harsh they enjoyed the freedom it offered.

The nomadic horsemen had a hard time adapting their way of life to cultivated land. Farms could not be converted to grasslands in one season, and although crops raised on cultivated land produced lots of food, they didn't grow back quickly and produce a constant supply of food like grass. For this reason the Huns mostly likely kept their families in their homelands across the Danube while they pillaged; the Mongols returned home after they plundered; and the Turks adapted to a semi-nomadic way of life. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

Steppe Horseman Animals: Sheep and Goats

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The most numerous and valuable of the Steppe horsemen' principal animals, sheep provided food, clothing, and shelter for Steppe horseman families. Boiled mutton was an integral part of the Steppe horseman diet, and wool and animal skins were the materials from which the Steppe horsemen fashioned their garments, as well as their homes. Wool was pressed into felt and then either made into clothing, rugs, and blankets or used for the outer covering of the gers [or tents]. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols ]

“Dried sheep dung was collected and used for fuel. Though the Steppe horsemen used wood and currently also use coal as fuel sources, animal dung was often the most readily available source. Women, and secondarily children, were responsible for gathering the dung. Survival of young sheep (and other animals) was vital to maintaining the pastoral-nomadic way of life, and a significant responsibility for Steppe horseman women was to coax the ewes to nurse their young.

“Goats were not as pervasive as sheep in the Steppe horseman flocks, but the Steppe horsemen consumed goat meat, milk, and cheese. The poor wore goat skins; and in more modern times, goats have become valuable as the source for cashmere. Because goats were not as tough and needed more care than sheep, the Steppe horsemen kept fewer goats. In addition, because goats consume the grass to the root when they graze, they devastate the grasslands, resulting in desertification. Steppe horsemen in traditional times therefore limited the number of goats in their flocks. Modern demand for cashmere caused many herders in the 1990s to increase their numbers of goats, potentially undermining the traditional ecological balance.

Steppe Horseman Animals: Camels and Yaks

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The Bactrian or two-humped camel permits the Steppe horsemen to transport heavy loads through the desert and other inhospitable terrain. The camel is invaluable not only for transporting the folded gers and other household furnishings when the Steppe horsemen move to new pastureland, but also to carry goods designed for trade. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols ]

A camel could endure the heat of the Gobi desert, could drink enormous quantities of water and then continue for days without liquid, required less pasture than other pack animals, and could extract food from the scruffiest shrubs or blades of grass — all ideal qualities for the daunting desert terrain of southern Mongolia.In addition to the camel's importance for transport, the Steppe horsemen valued the animal's wool, drank its milk (which can also be made into cheese), and ate its meat. [Source: "The Camel in China down to the Mongol Dynasty," by Edward H. Schafer, in Sinologica 2 (Basel: Verlag für Recht und Gesellschaft, 1950]

“Yaks and oxen require excellent grazing grounds and cannot endure well in the deserts and other marginal areas. They are found primarily in the steppelands, and thus there are fewer of them than sheep or goats. Yaks offer meat and milk, and the Steppe horsemen often use yak and ox carts to transport their belongings as they migrate from one region to another.”

Nomadic Life

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The Mongolian and Central Asian pastoral nomads relied on their animals for survival and moved their habitat several times a year in search of water and grass for their herds. Their lifestyle was precarious, as their constant migrations prevented them from transporting reserves of food or other necessities. Rarely having the luxury of surpluses to tide them through difficult times, they were extremely vulnerable to the elements. Heavy snows, ice, and droughts (judging from contemporary times, droughts afflicted Mongolia about twice a decade) jeopardized their flocks and herds and heightened their sense of fragility. The spread of disease among the livestock could also spell disaster. Herders hunted and farmed to a limited extent but were dependent on trade with China in times of crisis. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols ]

Much of Mongolia has changed little since the days of Genghis Khan. About 40 percent of Mongolia's 2.5 million people are herders or nomadic. Sometimes you can travel the steppes and deserts and not see a soul for miles and miles, and suddenly a herder will come from nowhere with his animals.

Describing some Mongolian nomads, Cynthia Beall and Melvyn Goldstein wrote in National Geographic, "They appeared suddenly from a ravine, two nomad horsemen driving a herd of sheep across the path of our truck. On and on the animals came, a sea of brown, black, and white against the golden grasses of the broad plain. The herders, darting here and there on mounts no bigger than ponies, ride with fluid grace worthy of their famed ancestors, the Mongol cavalry."

Nomads are largely self-sufficient. One nomad said, "Because we have our own animals to give us much of what we need, were are better than the people in the cites." If some disaster strikes and the nomads lose their animals, they are in big trouble. They are helpless and face death. Herders often put the welfare of their animals above the welfare of themselves.

Book: "Changing World of the Mongolia Nomads" by Cynthia Beall and Melvyn Goldstein, professors at case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. "Shiki Yuboku" (Four Seasons, Nomadism) is a seven-hour-40-minute film about Mongolian nomads by Japanese film director Yoji Yamada.

Nomad Seasonal Rhythms

Nomad families spend the short summer in the mountains, where their tend sheep, goats, and camels which graze in Alpine pastures, and then move in the winter down to their village, where many live in mud houses.

During the winter the herds typically lose 40 percent of their weight and are sustained by hay cut in the autumn. The animals need about 25 pounds of hay a head per week. After the first freeze, often enough sheep and goats are slaughtered to last the whole winter. A family may kill 150 animals over three days.

The winter is often one of the busiest times. The animals begin bearing young but are weak from lack of food. Special care has to be taken to make sure the deliveries go smoothly and the young survive. Small ones are often brought in the gers to stay warm. The winter evenings are spent singing, cooking and telling stories.

In the spring and summer the horses are milked six times a day to collect milk for koumiss. In May the men and children begin preparing for the sporting events in the Naadam festival while women spend their free time knitting, sewing and spinning.

Nomad Migration

Herders have traditionally moved their animals between the high summer pastures of the mountains and their villages camps on steppes where they spend the winter. They pick up and move two or three times a year, typically in May and October, usually remaining within a 25-square mile area, and relocate from November to April in a winter camp with some stone shelters for the animals.

Herders will stay in an area as long as the there is enough grass. Where grazing land is more scarce nomads roam across large swaths of empty plains, mountains and grassland, having to travel longer distances and pack up and move maybe ten or so times a year or as often as twice a week. Moving the animals around also allows the grass to grow back.

There are no fences, except around cities, Herders have traditionally takes their animals to where the pastures were best. In the dusty steppes and sandy deserts they find places where wild grasses grow tall and find places in the mountains were the pastures are sweet.

Men traditionally rode on horses, Women rode on horseback or on the pack animals. Bactrian camels were traditionally used to move possessions. Everything was load on their backs: ger parts, carpets, pots and pans, shelves, stoves. These days trucks often fulfill this duty.

It takes a nomad around two weeks to slowly move his animals, which graze along the way, 100 kilometers. The nomads don’t need maps and GPS devices; they use the sun, stars, the shape of hills and mountains and landmarks to find their way.

Seasonal Migrations

The pastures are divided according to season---summer, spring/fall, and winter--- based on the amount of grass and when the grass is sufficient to eat, which is often determined by geography, climate conditions and season. The summer pastures are usually located in the north in the steppe areas or in the mountains. These areas have abundant, lush grass but heavy snows make it impossible for the animals to graze. In the winter the animals are taken to the south or to the desert and semidesert zones, where autumn rains are imperative for producing grass for animals to eat.

Kazakhs that lived near mountains migrate between the high pastures in the summer and the river valleys in the winter. The distance between pastures and the river valleys is often less than 80 kilometers. During the summer they often set up their yurts in the open pastures and gather for circumcision ceremonies, weddings, funerals, festivals and family reunions that often feature young girl dancers in beaded costumes and horse races.

Between the main summer and winter migrations nomads stay briefly at fall and spring pastures. Nomads that move overland between the northern steppes and the southern semideserts are known as “meridanal” nomads while those that migrate up and own the mountains are called “vertical” nomads. The nature of the migration, the type of grass available and the market price for animals and family and clan needs determine which animals are raised.

Zud

The Mongolian word “zud” (“dzud”) refers to weather conditions that prevent animals from getting enough grass to eat. It usually refers to a cycle of summer droughts followed by an extraordinarily cold winter with heavy snow and ice. Animals, underfed from the drought, simply don’t have the strength to fight and endure spells of harsh cold and dig through ice and snow for grass.

The zud causes great hardship for herders on the steppe, often killing off entire herds of animals. The drought in the summer leaves animals weak and skinny, plus causes shortages of hay needed to keep the animals going in the winter. The most difficult times are often in the following spring when the food supplies begin to run out. When the animals die in the winter, they are frozen in cold temperatures. The meat can be eaten later.

Zuds tend to be localized events that affect some people seriously and don’t affect others. Cows are often the first to go followed by horses, sheep, camels and goats. One herder said, “The Zud”it happens sometimes. It’s survival. It’s our karma.”

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, Comptom’s Encyclopedia, Lonely Planet Guides, Silk Road Foundation, “The Discoverers “ by Daniel Boorstin; “ History of Arab People “ by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “Islam, a Short History “ by Karen Armstrong (Modern Library, 2000); and various books and other publications.

Last updated February 2019