HORSEMAN RELIGION

Buryatia Shaman The Altaians, Tartars, Turks, Mongols, Burjats and Yakuts of Central Asia all shared similar religious beliefs. Their universe was divided into three spheres: the upperworld or sky, the middleworld or earth, and the underworld or hell. Each world was divided into layers. The skyworld for example had seven or nine layers with the most revered gods at the top and lower echelon gods at the bottom.

The supreme deity was known as "the sky" or "the creator." He was a benevolent god with unlimited wisdom, power and authority. His sons and messengers occupied the layers of heaven below him. There is a set of evil gods in the underworld, and many Central Asian myths are about battles between them and the forces of good.

The Mongols had thousand of gods. They worshiped the sun, moon, stars, rivers and mountains. Mongol shaman and priest communicated with the gods and relayed the information to Mongol leaders such as the Great Khan. Fire worship was a part of the burial ritual for Scythian and other horsemen.

Websites and Resources: Mongols and Horsemen of the Steppe: “The Horse, the Wheel and Language, How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes shaped the Modern World", David W Anthony, 2007 archive.org/details/horsewheelandlanguage ; The Scythians - Silk Road Foundation silkroadfoundation.org ; Scythians iranicaonline.org ; Encyclopaedia Britannica article on the Huns britannica.com ; Wikipedia article on Eurasian nomads Wikipedia Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; The Mongol Empire web.archive.org/web ; The Mongols in World History afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols ; William of Rubruck's Account of the Mongols washington.edu/silkroad/texts ; Mongol invasion of Rus (pictures) web.archive.org/web ; Encyclopædia Britannica article britannica.com ; Mongol Archives historyonthenet.com

See Separate Article SHAMANISM AND FOLK RELIGION IN MONGOLIA factsanddetails.com

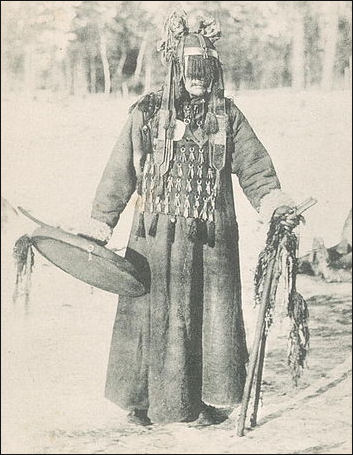

Horseman Shaman

Steppe religious life usually centered around the clan shaman — a man or a woman whose spiritual power was so great he or she had to be separated from society. When in a trance the shaman could communicate with dead, the gods, demons and natural spirits. He also could make out the form and destiny of a person's soul and heal illnesses with this knowledge.

Illnesses, the steppe people believed, were caused by straying souls who became influenced by demons. The shaman's objective was to bring the soul back, a task that was usually performed while in an ecstatic trance.

Shaman were believed to be reincarnated as birds, animals and warriors during ceremonies. The often used tambourines and wore clothes and hats that symbolizes bridged the world real world with spiritual world. To reach the skyworld the shaman often literally and figuratively climbed a ladder or pole.

Shaman are people who have visions and perform various deeds while in a trance and are believed to have the power to control spirits in the body and leave everyday existence and travel or fly to other worlds. The word Shaman means "agitated or frenzied person" in the language of the Manchu-Tungus nomads of Siberia.

Shaman are viewed as bridges between their communities and the spiritual world. During their trances, which are usually induced in some kind of ritual, shaman seek the help of spirits to do things like cure illnesses, bring about good weather, predict the future, or communicate with deceased ancestors.

Shaman use various techniques to put themselves into trances: taking hallucinogenic drugs, asphyxiating themselves, and/or being taken over by hypnotic drums, dance rhythms or chants. When in a trance they have visions, speak in strange voices or languages, communicate with dead ancestors, gods, demons and natural spirits, and receive instruction from them about how to help the person who has sought the shaman's help. Maybe the patient has broken a taboo, offended a spirit or ancestor or lost his soul.

See Separate Article ANIMISM, SHAMANISM AND TRADITIONAL RELIGION factsanddetails.com

Mongol Shamanism

shaman of north Mongolia

Shamanism is the traditional religion of the nomads and horsemen that occupied Mongolia. Mongolians have traditionally believed that shaman had the ability to “soul travel” and cure the sick. This belief helped them deal with the unexplained aspects of their natural world and its unanticipated hardships. Shamanism is still practiced by the Mongolians and practiced by minorities such as the Tsaatan, Darkhad, Uriankhai and Buryats.

In Mongolia both men and women can be shaman but a distinction is made between hereditary ones and those who have become shaman after suffering a serious illness. Shaman have traditionally been sought out to cure sickness and act as intermediaries between the human and spiritual world, often by going into a trance sometimes for hours at a time. During the Great Sacrifice, traditionally held on the third day of the after the lunar New Year, shaman divined the future from cracks made in heated sheep shoulder blades.

Shamanism also remains alive in common daily rituals such as rubbing holy stones together and the traditional blessing of dipping a finger in milk and flicking it towards the sky in honor of local spirits. After a statue of Stalin was removed, peasant sprinkled milk on it to "prevent his angry evil spirit from returning to haunt them. "

Tibetan Buddhism practiced in Mongolia is influenced by shamanism. During Tibetan New Year’s celebrations shaman have traditionally presided over parades in which Buddhist images were pulled on carts with the head of a magical green horse.

See Separate Article MONGOL RELIGION factsanddetails.com

Ovoos

Ovoos in Tibet

Ovoos are piles of stones, often with prayer scarves to attached them, that are still widely found in Mongolia today. Originally the product of shamanistic practices, they are found scattered across the steppe and desert and in the mountains, marking sacred places or auspicious points on a journey or dwelling place of spirits. Some are just a pile of a few stones. Others are elaborate arrangements with prayer flags and poles with the skulls of yaks or cattle on top of them. Sometimes skulls of highly prized horses rest on top.

Some ovoos mark the sites of annual sacrifices set by the lunar calendar. Many have vodka bottles and scarfs left around them that have been left as offering. The land around the ovoos is regarded as sacred and hunting, digging or cutting down trees or any other disrespectful act is taboo. Mongolians believe that anyone who does such a thing will fall sick or even die.

When encountering an ovoos one is supposed to walk around it three times add tree stones and say a prayer. Many are placed along roads. When encountering one of these you are surprised to drive on the left side. At large ovoos Mongolian drivers often stop and say a prayer and make an offering. Festivals are held at major ones to celebrate the new year and pray for rainfall and grass for animals. These events usually include feasting, prayers by monks and traditional sports.

Mongolian Shamanist Rituals

Describing a Mongolian shaman named Bajlmaa, Yoon Suh-kyung wrote in the Korean Herald, "Dressed in a dark brown frock draped with ripped cloth and sparkling materials, she was an overwhelming presence...As her assistant scurried about preparing the ritual table with incense burners, wine goblets, plates of food, Baljimaa continued speaking in a booming voice...When the preparations were complete, she stood at attention with her big brass gong and mallet-like stick in hand."

"Hitting the gong rhythmically and chanting in the guttural tones of Mongolian," Yoon wrote, "Baljimaa walked back and forth across the stage, calling for the gods to possess her body. For more than 30 minutes she chanted, rousing the crowd to the height of expectation. Then suddenly, she started to throw up, or at last, it sounded as of she was throwing up, crouched at the corner of he stage with her back to the audience. 'My body has been tainted by people in the audience. Is there anybody who has had a death in the family recently or is thinking bad thoughts about this ritual? If so leave," she growled.

"After yet another round of preparations by the assistant, which included trying to get a larger flame to form on the burner that had been installed to take the place of a real fire, Baljimaa returned to walking sedately back and forth on the stage, banging the gong in hypnotic rhythm. But after another 15 minute, with not a spirit in sight. Baljimaa threw up her gong, saying, "It's not working...we need to guide the spirits, they are refusing to find their own way here."

Horseman Superstitions

Steppe nomads have traditionally been very superstitious, going out of their way not offend any spirits because their fortunes are so mercilessly and whimsically tied to nature. Even when they were desperately hungry and thirsty the first cup of water and morsel of food was thrown outside the tent as a an offering to appease their gods. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

The Mongols were afraid of thunder and lightning, which made sense because they so vulnerable to lighting in the open steppes. During storms the Mongols would warp themselves in black felt inside their tents and throw strangers---who were considered bad luck---out into the cold. They also wouldn't go anywhere near an animal struck by lighting out of fear that it too would bring misfortune. [Source: "Riding the Iron Rooster" by Paul Theroux]

Horseman Sacrifices

Yuan dynasty iron magic square

Horse burial, horse sacrifices and fire worship were elements of Scythian and other horse people burials. Horses are still sacrificed and their dried corpses are hung from long sticks in the Altai Mountain region of Mongolia. This ritual is performed because it is believed that only a sacrificed horse can carry the shaman to heaven.

During sacrificial ceremonies the head of a cow was hung from a tree and stones arranged in a rectangular pattern were placed beneath it. The tree symbolized a shelter for souls and animals were cooked nearby. Altaic people believed that dead people could eat offerings by smelling the smoke.

Horseman Human Sacrifices

Executed relatives and servants were often buried with a deceased chief or king. When a Mongol khan died many relatives and servants were slain and buried with him along with large numbers of horses and gold objects. Marco Polo said he witnessed the funeral of the Mongol leader Mangou and wrote that the 20,000 people who witnessed the funeral were slain.

When a king of a chief died his cooks, grooms, butlers, wives, servants and body guards were often killed as part of the funeral ceremony. One explanation of this is that the deceased could accompany the dead leader to heaven. Another is that having their lives bound with that of the king, the wives, bodyguards and servants were less likely to plot against him and more likely to do what ever they could to make sure he stays alive.

See Funerals of Different Horsemen Groups

Horseman Funerals

The nomadic and semi-nomadic people of Central Asia and the Russia steppes, including the Turks, Mongols and Scythians, traditionally have followed similar funeral and burial customs that date back to at least to 7th century B.C. and endured well into the Middle Ages.

Funeral for Hulegu Khan

Commoners were given fairly ordinary funerals. After they died they were embalmed and placed on wagons. For 40 days they were carried around to the homes of relatives and friends. The people who carried the body were feasted by the relatives of the dead and food was offered to the deceased. They were buried deep chamber catacombs, pit graves or undercut graves. Elements of these customs survive in Central Asia.

Chiefs and kings were obviously sent with more fanfare. They were often buried in roofed underground chambers, sometimes topped with great mounds called kurgans, along horses and sometimes many material goods. Sometimes a monuments were raised in their honor. A 12-foot-high tombstone of a Mongolian king dated to A.D. 731.

When a king died, his followers cut their hair, cropped their ears and slashed their foreheads, hands and noses. The king’s body was embalmed, stuffed with incense and spices, and loaded in a wagon. The body was then taken through tribal areas ruled by the king and people there were expected to cut their hair and bodies as the followers had. After this pilgrimage was completed the body was taken to a special places where chiefs and kings were buried.

At the burial place a deep grave was dug and, sometimes, lined with spears. The kings body was placed inside, sometimes with horses and cattle that had been killed for the occasion. Sometimes 50 to 100 animals were killed. The grave was then sealed. Often a large mound of dirt and stones was placed on top of it.

See Funerals of Different Horsemen Groups

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, Comptom’s Encyclopedia, Lonely Planet Guides, Silk Road Foundation, "The Discoverers" by Daniel Boorstin; "History of Arab People" by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); and various books and other publications.

Last updated February 2019