SCYTHIANS

one vision of

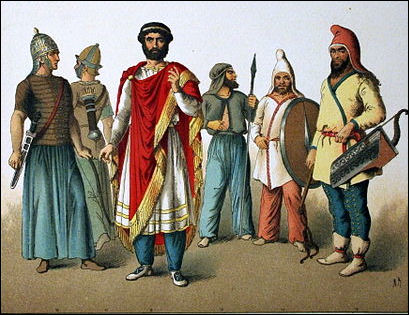

a Scythian warrior The Scythians were Indo-Iranian horse people who migrated from Central Asia to the European Steppe north of the Black Sea around 700 B.C. For 400 years they dominated an area that stretched from the Danube across the Ukraine, Crimea and southern Russia to the Don River and the Ural Mountains and then mysteriously vanished. [Source: Mike Edwards, National Geographic, September 1996]

The Scythians preceded the Huns, Turks and Mongols by many centuries. Never constituting an empire, they were a network of culturally similar tribes that ranged from Siberia to Egypt almost 3,000 years ago and faded away around A.D. 100. The Scythians were not a unified group but rather a confederation of related, warring nomadic tribes. The Scythians did not have a written language It is believed that they spoke an Indo-European language similar to Persian.

Andrew Curry wrote in Discover: The Scythians were a seminomadic culture that once dominated the steppes of Siberia, central Asia, and eastern Europe. Beginning around 800 B.C., the Scythians thundered across the central Asian steppes, and within a few generations, their art and culture had spread far beyond the steppes of central Asia. The Scythians’ exploits struck fear into the hearts of the ancient Greeks and Persians. Herodotus wrote about their violent burial customs, including human sacrifice (which the Arzhan 2 find tends to confirm) and drug-fueled rituals. He speculated that they came from mountains far to the east, in the “land of the gold-guarding griffins.” [Source: Andrew Curry, Discover, July 2008]

The Scythians inspired such terror among the Greeks that they are credited with inspiring the myth of Centaur. Some scholars believe that the Biblical prophet Jeremiah was referring to the Scythians when he warned the Israelites: “Behold a people comes from the north...They lay hold of bow and spear, they are cruel, and have no mercy. The sound of them is like the roaring of the sea; they ride upon horses, arrayed as a man for battle against you, O daughter of Babylon.”

Some scholars believe that the Biblical prophet Jeremiah was referring to the Scythians when he warned the Israelites that warriors would come who "are cruel and have no mercy; their voice roareth like the sea and they ride upon horses, every one put in array, as men for war against thee."

Many aspects of Scythian history and daily life are still veiled in mystery. They had no written language. No one knows exactly where they came from or why their empire collapsed. Historians do not even known if they had a capital and if they did where it was. Russian scholar Nadezhda told National Geographic, "I'm inclined to think that there was no capital. Perhaps the capital was wherever the king happened to be."

See Separate Articles SCYTHIAN LIFE, CULTURE AND GOLD factsanddetails.com ; HERODOTUS ON THE SCYTHIANS factsanddetails.com ; HERODOTUS ON SCYTHIAN BELIEFS AND CUSTOMS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources: Mongols and Horsemen of the Steppe: “The Horse, the Wheel and Language, How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes shaped the Modern World", David W Anthony, 2007 archive.org/details/horsewheelandlanguage ; The Scythians - Silk Road Foundation silkroadfoundation.org ; Scythians iranicaonline.org ; Encyclopaedia Britannica article on the Huns britannica.com ; Wikipedia article on Eurasian nomads Wikipedia Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; The Mongol Empire web.archive.org/web ; The Mongols in World History afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols ; William of Rubruck's Account of the Mongols washington.edu/silkroad/texts ; Mongol invasion of Rus (pictures) web.archive.org/web ; Encyclopædia Britannica article britannica.com ; Mongol Archives historyonthenet.com

Herodotus and Other Sources on the Scythians

Scythian man The Scythians were contemporaries of the Greeks. Much of what we know about them is based on accounts by Herodotus, the founding father of history, who wrote about the Scythians in the 5th century B.C.. Other information about them has been gleaned from archeological excavations and accounts from other Greek historians.

Herodotus wrote extensively about the Scythians It is not clear how much was based on first hand observation or second hand accounts but the latter seems most likely. It is also not clear how extensively Herodotus traveled in the Black Sea-Dnieper River heartland of the Scythians On one journey around 450 B.C. he probably reached Olbia, 40 miles west of the Dnieper River.

Herodotus described the Scythians as savage warriors who committed many atrocities. Some think that Herodotus gave the Scythians an unjustified, prejudiced bad rap and in all probability they committed no more atrocities than the Romans, Persians, Egyptians or even the Greeks themselves.

A. I. Melyukova and Crookenden Julia wrote in the “Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia”: The basic sources for the study of Scythians and Sarmatians "are the testimonies of the Greek and Roman authors who were interested in different aspects of the life of barbarians, archeological and ancient epigraphical data. Written sources describing the Scythians are more numerous, but they contain only fragmentary and often contradictory evidence. The archeological materials dating back to the Scythians and Sarmatians are now enormous; thousands of burial sites have been examined, helping us to formulate and to resolve a number of questions about the Scythian and Sarmatian tribes, their material and spiritual culture. Along with this it must be said that the available written and archeological sources still do not enable us to give any definitive answer to certain important questions about both Scythian and Sarmatian history and archeology. These questions are still being discussed and are explained in different ways by different scholars. However, the study of the Scythians and Sarmatians in the Soviet era has made very considerable advances, particularly through the accumulation of new archeological sources in the post-war period.” [Source: The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, edited by Denis Sinor. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1990]

Scythian History

Although they had no written language many scholars believe the Scythians spoke an Iranian language. German Scythian expert Hermann Parzinger told National Geographic: “From ancient sources we know the names of several tribes, and they seem to be Iranian names. There were different groups but they had the same way of life and same burial customs.”

Andrew Curry wrote in Discover: Archaeologists say the Scythians’ Bronze Age ancestors were livestock breeders living in the highlands where modern-day Russia, Mongolia, China, and Kazakhstan intersect. Then something changed. Beginning around 1000 B.C., a wetter climate may have created grassy steppes that could support huge herds of horses, sheep, and goats. People took to horseback to follow the roaming herds. Around 800 B.C., all traces of settlements vanish from the archaeological record. [Source: Andrew Curry, Discover, July 2008]

The Scythians were living in the Tuva area of Central Asia and Siberia in the 9th century B.C. They arrived in the Black Sea region of present-day Ukraine from Central Asia on a migration route that skirted the northern reaches of the Caspian Sea. They were probably seeking grazing land for their horses and other animals. Excavated graves of people who lived in the Black Sea region before the Scythians arrived have revealed skulls with Scythian arrowheads impeded in them. These early inhabitants were known as the Koban culture.

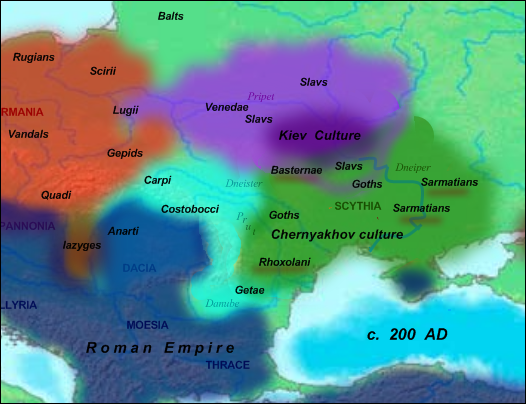

Scythia in the Roman era

For a period of 30 years in the 6th century B.C., Herodotus wrote, the Scythians burst out the Black Sea region and across the Caucasus and raided communities in Asia Minor and the Middle East. They migrated as far westward as Germany and captured land formerly controlled by the Medes in present-day western Iran and by the Assyrians in Mesopotamia. The pillaged cities as far away as Palestine and Babylon before they were finally driven back by the Medes.

At the height of their power in the 4th century B.C., the Scythians controlled an empire that covered much of what is now southern Russia and the Ukraine and stretched 4,000 miles from eastern Europe to Mongolia.

Scythian Warfare

According to Herodotus the Scythians were ruthless and nearly invincible warriors who made cloaks from their victims scalps and drank from their skulls and sacrificed one out of every hundred prisoner of war. Wealthy Scythians reportedly gilded the insides of the skulls of their enemies and used them as drinking cups.

Scythians are credited with creating the first truly effective cavalry and employing tactics described as an ancient version of the blitzkrieg. They attacked their enemies on horseback and cut down their enemies with weapons mentioned below. They were difficult to fight against because moved swiftly on horseback. The nomadic ways made them difficult to attack and even find. There is also archeological evidence that the Scythians participated in battles and may have even lead charges.

The Scythians and their cousins the Sarmatians were the earliest recorded group of steppe warriors. In a review of Erik Hildinger’s “Warriors of the Steppe”, Christopher Berg wrote: “Herodotus first made the “distinction between the Western and steppe ways of warfare.” Their style of war was simple but effective: they never engaged the enemy preferring to remain just out of harm’s way, and, feigning retreat, drew their foe unwittingly into an ambush. Hildinger notes, “Steppe warfare at its purest is one of travel across great distance, missile warfare and, if it is advantageous, strategic retreat before the enemy until attrition, exhaustion or isolation have made his defeat inevitable.” The example of Crassus’ defeat at Carrhae illustrates the effectiveness of feigned retreats and the ability to neutralize opponents from a distance. Another tactic employed by other Barbarian tribes in Eastern Europe was encircling the enemy. Feigned retreats, drawing the enemy out, encirclement, and horse archers would be employed time and again by all steppe cultures with devastating effect. [Sources: “Warriors of the Steppe: A Military History of Central Asia 500BC to 1700AD” by Erik Hildinger (Da Capo Press, 1997); Christopher Berg, Sam Houston State University deremilitari.org /^]

Scythian Weapons

Scythians used spears, battle-axes, iron swords, composite bows, and arrows with iron arrowheads. Iron was a relatively new invention and the Scythian smelted their own iron ore. Arrowheads were also made of bronze and bone. Many were barbed like a fishhooks, which made them difficult to take out, and tore up the flesh when they were.

The Scythians were skilled archers. The used different arrows depending on the situation. When they hunted birds they used a delicate arrowhead because they aimed for the eye. Warriors carried up to 200 needle-sharp arrows into battle. Some were poisoned. Ovid described a “poisonous juice” brewed from a mixture of snake venom, purified blood, and dung. that “clings to flying metal.”

Only two Scythian bows have been unearthed. One was 32 inches long and double curved like the Greek letter sigma (Σ). It was laminated and made of trips of willow and alder joined with fish glue. According to an inscription at the Greek Black Sea trading town of Obia one of these bows fired an arrow 570 yards (over half a kilometer).

Scythians carried gortos (a combination bow and arrow holder) and wore armor consisting of bronze or iron scales sewn into leather that provided protection from arrows and spears but was also flexible and relatively lightweight.. Noblemen are believed to have fought with hammered gold helmets and headdresses, and decorative gold scabbard that were found in their graves.

Scythians Women Warriors and the Amazon Myth

Scythian archer Some scholars believe that Scythians are the source of the Amazon myth and that the Amazons were a real-life tribe of large women warriors that existed in Asia Minor. Supporting this claim are reports from many different sources with the same information — the queen’s names, their battle tactics and style of dress — and the discovery of a number of burial chambers in the steppes of Russia, the Ukraine and Central Asia women warriors decked out in gold and jewels and outfit with a variety of weapons.

Herodotus relayed stories he heard of Scythian female warriors in the Black Sea that fought side by side with the men in battle and reportedly were not allowed to become warriors until they killed an enemy man. He also said that in some cases these women removed one of their breasts to make shooting a bow easier. One Russian archeologist told National Geographic, "The Greek writers don't mention women warriors among the Scythians. They had to be armed to defend the place where they lived while the men were away."

Two groups of women warrior that Herodotus called Amazons and the Scythians called Oirpata ("killers of men") ultimately went off together and formed their own tribe. These women were enthusiastic about making love but they didn’t want to be domesticated. One reportedly said: “We are riders, our business is with the bow and the spear...ut in your country....women stay at home in their wagons occupied with feminine tasks, and never go out to hunt, or for any other purpose.”

The grave of one steppe nomad woman thought to be a woman warrior was discovered in 1969 in a kurgan burial chamber excavated near Alma Alta, Kazakhstan. Buried in a 5th century B.C. and initially identified as the Issayk Old Man, the woman was dressed in a boots, trousers, an elaborate 25-inch-tall golden headdress and leather a tunic decorated with some 2,400 arrow-shaped gold plaques as well as dear heads, moose and snow leopards made from gold.

Amazons, see Greeks

Scythians Versus Persians

In 513 B.C., the Persian King Darius I marched a 700,000 man army over 1,000 miles to lead an attack on the Scythians. Historians believe that he may have been trying to strengthen his borders against invaders or trying the shut off the grain supply to his enemies the Greeks.

When Darius' soldiers advanced on the Scythians, the Scythians used “tactical retreat” and fell back and stayed out of range, setting the steppe on fire and poisoning wells. According to Herodotus, Darius wrote a message to the Scythian ruler that essentially said: Stop running and fight like men. The Scythian leader Idanthyrus replied that the Scythians had no cities or crops to defend, "we have the graves of our fathers; come, find these and try to destroy them; then shall you find whether we will fight you."

Itching for battle, Darius deployed thousands of soldiers in attack. The Scythians only showed contempt for these tactics. According to Herodotus, the Scythians were so little concerned by the Persians attack they broke ranks to chase a rabbit while awaiting their charge. Fed up, Darius took his army back to Persia.

End the Scythians

The Scythians were driven out of much of their empire by another group of horsemen, the Sarmatians, and were defeated in a battle by Philip II of Macedon, the father of Alexander the Great, in the forth century B.C. Excavation of Scythian sites show nothing in third century B.C.

The Greek geographer Strabo wrote that some Scythians move westward during this period into present-day Transylvania, establishing an independent Little Scythia, and others migrated south to the Crimea. According to Strabo the a Greek army from the kingdom of Pontus in Anatolia attacked the last enclave of Crimean Scythians in 108 B.C. and destroyed the Scythian force and burned their city of Neapolis.

No one is sure why the Scythian empire collapsed. Before they were defeated by Philip II they began to settle down and marry other tribes and abandon herding. Excavations from the forth century B.C. suggests that the Scythian herds of animals were declining. Some tombs from this period contained stoves, symbolic of the comfort of and warmth of a home, some archeologist believe, and an indication that the Scythians were abandoning the nomadic life.

Other theories include a prolonged drought or fire that degraded their grazing land; invasions from Sarmatians, a rival horse people from the east that encroached on eastern Scythian land in the 4th century B.C., or a conflict the denitary demands of an empire and nomadic wanderlust. Some scholars theorized that the Scythian love of alcohol may have led to their demise. See Scythian Life Below.

Yevgeny Chernenko, Ukraine's most respected archeologist told National Geographic, "The truth is that we simply don't know what happened. Scythia may have just collapsed from internal pressures, like the Soviet Union."

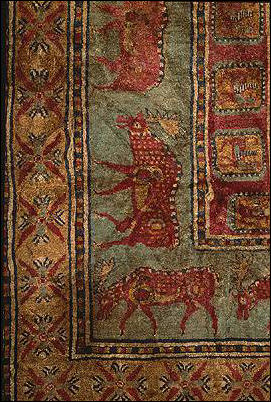

Scythian Religion and Burials

It is believed that the Scythian worship creatures depicted in their art — stags, fish, and mythological griffins — and that these animals had magical meanings. Fire worship was a part of the burial ritual for Scythian and other horsemen. Scythian purified graves with torches.

The Scythians believed their dead ascended to another world where they would keep their social position and wealth. Tombs were outfit with objected deemed useful in the next world.

Scythian tombs contain sacrificed servants and decapitate horses. Scythian mummies show signs of primitive embalming: Internal organs were removed and replaced with grasses. f

The burial customs of the Scythians are thought to be the same or similar to those of the Pazyryk See Pazyryk Burial Customs

Scythian Horse Sacrifices

The Scythians revered their horses in death as they did in life and practiced horse burials and sacrifices. The number of horses someone was buried with was often a sign of wealth. One kurgan found in Ukraine contained 400 horses arranged geometrically around one person.

Horses were often buried with their bridles intact. Sometimes they were adorned with decorative wooden bands with images of moose, griffins, horned lions and sheep. Many skeletons have been found without skulls which has lead archaeologists to speculate that some sort of dismembering ritual took place.

A Scythian kurgan excavated near the village of Berek in the Bukhtarma Valley in the Altai mountains in Kazakhstan in the early 2000s in Kazakhstan contained 13 horses than been frozen since around 500 B.C. Because the had remained frozen since the time they were buried their skin, hair, harnesses and saddles were still intact.

The horses buried near Berek were placed on the north side of the kurgan while the coffin of a man — believed to have been a nobleman who owned all the horses — was on the south. The horses were buried on two levels, covered by layers of twigs and birch bark. The horses had been sacrificed in full regalia but appeared to be well past their prime. One was eighteen and a had trauma marks on its skull indicated that it was probably killed with a pick-ax.

Sarmatians Dacians Scythians

Human Sacrifices at Funeral for a Scythian King

Herodotus described a funeral of deceased king in which Scythians expressed their grief by hacking out their hair, cutting off parts of their ears, piercing their left hands with arrows and slicing their arms open with knives.

The embalmed body of the king was taken from one encampment to another until he finally arrived at his tomb. Prized possessions were placed in the grave and concubines, servants and horses were sacrificed. A year after burial, Herodotus said, 50 servants and 50 horses were killed and planted on posts around the royal Kurgan. The horses were stood upright and the dead men were mounted on top of them..

Describing the funeral Herodotus wrote: "When they put the dead in his grave on a bed, they fix spears on either side of the corpse and stretched above it wood planks bound with plaited rushes; in the burial's remaining open space they bury one of his concubines, after strangling her, and his wine bearer, cook, groom, valet, and message bearer. Also his horses, and the first fruits of anything else...having done this, everyone sets about raising a great mound of earth, showing the greatest zeal and rivalry with one another to make it as big as possible."

The tomb a chief contained a strangled servant, a decapitated horse, gold medallions silver cups used to drink koumiss and amphorae for wine.

Scythian Tombs

Kurgan Important Scythian leaders and warriors were buried in mounds known as kurgans. Thousands of kurgans remain despite the fact that thousands of others were plowed over to make room for farms. Those that remain often look like small isolated hills rising up from a potato or wheat field. Some of the kurgans rise as high 65 feet, the equivalent of towering mountains on endlessly flat steppe.

Scythians were probably not the only groups that made kurgans. Of the hundreds of kurgans that have been excavated only three can be linked with specific people. The tombs are dated within an accuracy of 10 to 15 years by matching the maker's or inspector's mark on ceramic vessels found in the tomb with a catalogue of such marks

The heaviest concentration of kurgans is along the lower Dnipro River, where the "Royal Scythians," described by Herodotus resided. Mamay Gora (south of the city of Zaporizhzhya, Ukraine) is the largest known Scythian burial site. It consists of seven large kurgans (burial mounds) and a 300 lesser ones.

The kurgan of the chief near Rzyhanovka at the southern end of in a line with 20 other kurgans, . running north to Nearby is a 20-foot-high kurgan believed to contain the remains of the chief’s relatives. The majority of the kurgans excavated by archeologist, who sometimes used bulldozers to get at the garves inside, have been stripped of their most valuable pieces befor the archeologist got to them by looters who tunneled into the burial chamber. Looting and grave robbing has become especially big problems since the collapse of the Soviet Union and people scramble to make money any way he can.

Scythian Tomb Features

The dead were buried with objects to be carried into the afterlife. Men were buried with an array of weapons, carriages with bells and horses with bridles and stone shrines with blackened hearths. Women were buried with gold rings on every finger and cloak with small gold plates sewn into the fabric. Both men and women were buried with mirrors.

The chief in one tomb wore red trousers and white caftan and surrounded by 150 finely-crafted gold objects included a sword with a gold handle, a gold necklace and silver drinking cup with an image of a griffin attacking a deer.

Scythians tombs found near Kiev are believed to be modeled after real-life homes. Fabrics covered the walls and ceilings and reed mats lined the floor. Food and wine were set out. Others were filled with many sacrificed horses and contained cut squares of sod from prime grasslands, seemingly to provide food for the departed's livestock in the hereafter, causing one scholar to speculate that kurgans were "symbolic pastures."

A mock hearth found in a 30-foot-tall kurgan of a chief near the village of Rzyhanovka, 75 miles south of Kiev, dated to a period of Scythian decline, led some archeologist to suggest that it may symbolize the comfort of and warmth of a home and may indicate the abandonment of the nomadic life for a more settled life.

Valley of the Tsars

Scythian Neapolis Mausoleum Some kurgans found in the Tuva region in Russia, north of Mongolia and dated to the 8th century B.C., are the size of football fields and made of sandstone from nearby cliffs. The area has been dubbed the Valley of the Tsar because the kurgans are so large that local people felt that only kings would be buried in them. Each kurgan contains several vaults with the highest ranking person, possibly a king, buried at the center, less ranking people buried further from the center and horses laid to rest near the perimeter. Few artifacts have been fond in the burial chambers because most of the tombs had been looted. [Source: Mike Edwards, National Geographic, June 2003]

There are four stone kurgans in the valley, each about a mile or so from the other and each thought to have belonged to a ruler in a single dynasty. One named Arazan 1 was excavated in the 1970s and was dated to the 9th century B.C., one of the oldest Scythian sites. Each tomb required hundreds if not thousands of laborers to make. Just bringing the sandstones slabs from the edge of the valley, several miles away to the tomb site was quite an undertaking. A typical tomb was comprised of sandstone slabs stacked in a circle 90 meters across and two meters high.

A vault dated to the 8th century B.C. in a kurgan called Arzhan 2, excavated in the early 2000s, was located four meters under the ground and was built of rot-resistant larch. Inside was a man estimated to be around 40 and a woman thought to be 30 or so. Both was found on their side, slightly curled like they were sleeping. Around them was an array of stuff to carry with them to the afterlife: thousands of gold ornaments, an ax, a whip, a bow, arrows, combs, jugs and bows, 431 amber beads from the Baltic, 1,658 turquoise beads, bronze, bone and iron arrowheads, stone ceremonial dishes. See Gold Objects, Jewelry, Below.

Scythian Legacy

Ethnic groups that live in remote Caucasus valleys in Iran, Georgia and southern Russia still speak an Iranian tongue similar to what the Scythians spoke and practice customs whose origins can be traced back to the Scythians.

Customs in Ukraine that are thought to be Scythian in origin include the taboo of forbidding the extinguishing of fires on St. John's Day, Christmas and New Year's Eve. The Ukrainians believe that Scythian kurgams were raised by mourners placing handfuls of earth on the grave, which means the larger the mound the larger the number of mourners.

According to scholars, Scythian culture is till very much in alive in North and South Ossetia, regions in Caucasus along the Russian and Georgian mountains. See Ossetians, Minorities, Russia.

Forensic Analysis of Scythian Warrior Mummies

Andrew Curry wrote in Discover magazine: “That the warrior survived the arrow’s strike for even a short time was remarkable. The triple-barbed arrowhead, probably launched by an opponent on horseback, shattered bone below his right eye and lodged firmly in his flesh.

The injury wasn’t the man’s first brush with death. In his youth he had survived a glancing sword blow that fractured the back of his skull. This injury was different. The man was probably begging for death, says Michael Schultz, a paleopathologist at the University of Göttingen. Holding the victim’s skull in one hand and a replica of the deadly arrow in the other, Schultz paints a picture of a crude operation that took place on the steppes of Siberia 2,600 years ago. [Source: Andrew Curry, Discover, July 2008]

“The man was crying, “Help me,” Schultz says. Thin cuts on the bone show how his companions cut away his cheek, then used a small saw to remove pieces of bone, but to no avail. Pointing to a crack in the skull, he describes the next agonizing step: An ancient surgeon smashed into the bone with a chisel in a final, futile effort to free the arrowhead. “Hours or a day later, the man died,” Schultz says. “It was torture.” The slain warrior’s remains were found in 2003, buried with those of 40 others in a massive kurgan, or grave mound, in southern Siberia at a site that archaeologists call Arzhan 2.

The Arzhan 2 grave mound contained the bodies of 26 men and women, most of them apparently executed to follow the ruler into the afterlife. One woman’s skull had been pierced four times with a war pick; another man’s skull still had splinters in it from the wooden club used to kill him. The skeletons of 14 horses were arranged in the grave. More impressive was the discovery of 5,600 gold objects, including an intricate necklace weighing three pounds and a cloak studded with 2,500 small gold panthers.

“In 2007, Schultz reported finding on a prince buried at the center of the Arzhan 2 mound. Using a scanning electron microscope, Schultz found signs of prostate cancer in the prince’s skeleton. This is the earliest documentation of the disease.” On another mummy Schultz noted “that the mummy’s teeth are surrounded by pitted bone — evidence of painful gum disease, probably the result of a diet rich in meat and dairy but lacking in fruits and vegetables. Between 60 and 65 years old when he died, the man was slim and just about 5 feet 2 inches. At some point he had broken his left arm, perhaps in a fall. His vertebrae show signs of osteo-arthritis from years of pounding in the saddle. Badly worn arm and shoulder joints testify to heavy use. “That kind of osteoarthritis and joint damage is very characteristic if you handle wild horses,” Schultz says. The clues reinforce what Parzinger and others have suspected: He belonged to the Scythians

Scythian Discoveries

In the 1940s horsemen mummies were found in the Altai Mountains, which run through Siberia and Mongolia. Later, after the fall of the Soviet Union, when some of the sites became more accessible for excavation, Scythian-related discoveries came at a faster pace. In the 1990s and 2000s well-preserved mummies — not skeletons — have been found at altitudes of 8,000 feet in the valleys of the Altai Mountains. Still other discoveries have been made on the coast of the Black Sea and the edge of China. [Source: Andrew Curry, Discover, July 2008]

Andrew Curry wrote in Discover magazine: “In the late 1940s, Soviet archaeologist Sergei Rudenko traveled to the Pazyryk region of the Altai Mountains and made some stunning finds. Richly appointed wooden chambers contained well-preserved mummies, their skin covered in elaborate, twisting animal tattoos. Their brains, intestines, and other organs had been removed and the corpses sewn up with horsehair. The dead had been dressed, armed, and laid to rest in chambers lined with felt blankets, wool carpets, and slaughtered horses.

In 1992 Russian archaeologists began a new search for ice lenses — and mummies. Natalya Polosmak, an archaeologist in Novosibirsk, discovered the coffin of an elaborately tattooed “ice princess” with clothes of Chinese silk at Ak-Alakha, another site in the Altai Mountains. Other finds in this area included a burial chamber with two coffins. One coffin contained a man, the other a woman armed with a dagger, war pick, bow, and arrow-filled quiver. She wore trousers instead of a skirt. The find lent credence to some scholars’ suggestions of a link between the Scythians and the legendary Amazons.

In the early 1990s, just a few miles from that site, Parzinger’s partner Vyacheslav Molodin uncovered the more modest mummy of a young, blond warrior. The burial style resembled that of Parzinger’s mummy, the one found at the Olon-Kurin-Gol River whose face was crushed by ice.

Study of Scythian Graves, Permafrost and Global Warming

There are concerns that global warming may soon put an end to the search for Scythians. Andrew Curry wrote in Discover magazine: “Rudenko’s dig diaries contain reports of weather far colder than what modern archaeologists experience in the Altai. “When you read descriptions from the 1940s and compare them with the climate of today, you don’t need to be a scientist to see there’s been a change,” Parzinger says. Geographer Frank Lehmkuhl from the University of Aachen in Germany has been studying lake levels in the Altai region for a decade. “According to our research, the glaciers are retreating and the lake levels are rising,” Lehmkuhl says. With no increase in the region’s rainfall, the change “can only come from melting permafrost and glaciers.” [Source: Andrew Curry, Discover, July 2008]

As the permafrost thaws, the ice that has preserved the Scythian mummies for so many centuries will thaw too. In the Olon-Kurin-Gol grave, the ice that once crushed the mummy against the roof of the burial chamber had receded nine inches by the time the chamber was opened. Within a few decades, the ice lenses may be completely gone. “Right now we’re facing a rescue archaeology situation,” Parzinger says. “It’s hard to say how much longer these graves will be there.”

Finding a Well-Preserved Half Frozen Scythian Mummy

Hermann Parzinger, a German archaeologist and head of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation in Berlin, and his Russian colleague Konstantin Chugonov excavated the tombs of the wounded warrior and the cancerous prince at Arzhan 2 and were tantalized by the possibility of finding a well-preserved mummy. [Source: Andrew Curry, Discover, July 2008]

Andrew Curry wrote in Discover magazine: “In the summer of 2006, his search took him to a windswept plain in the Altai Mountain range that is peppered with Scythian grave mounds. Parzinger worried that mummies in the highlands may not be around much longer, as global warming reverses the chill that has preserved them for millennia. A team of Russian geophysicists had surveyed the area in 2005, using ground-penetrating radar to look for telltale underground ice. Their data suggested that four mounds could contain some sort of frozen tomb. Parzinger assembled 28 researchers from Mongolia, Germany, and Russia to open the mounds, on the banks of the Olon-Kurin-Gol River in Mongolia. The first two mounds took three weeks to excavate and yielded nothing significant. A third had been cleaned out by grave robbers centuries earlier.

The radar data for the fourth mound — barely a bump on the plain, just a few feet high and 40 feet across — were ambiguous at best. But a thrill went through the team as they dug into it. Buried under four and a half feet of stone and earth was a felt-lined chamber made of larch logs. Inside was a warrior in full regalia, his body partially mummified by the frozen ground.

Researchers recovered the mummy intact, along with his clothes, weapons, tools, and even the meal intended to sustain him in the afterlife. He shared his grave with two horses in full harness, slaughtered and arranged facing northeast. Mongolia’s president lent the team his personal helicopter to shuttle the finds to a lab in the country’s capital, Ulaanbaatar. The mummy’s body spent a year in Germany; his clothes and gear are at a lab in Novosibirsk, Russia.

Before Parzinger opened his grave, the warrior had lain for more than 2,000 years on an ice lens, a sheet of ice created by water seeping through the grave and freezing against the permafrost below. The mummy “had been dehydrated, or desiccated, by the ice in the grave,” Schultz says. The combination of ice and intentional preservation resulted in remarkably resilient specimens. When Schultz shows me the mummy, housed in the same lab as the skeleton of the wounded warrior, the temperature is a comfortable 70 degrees, and sunlight streams onto its leathery flesh.

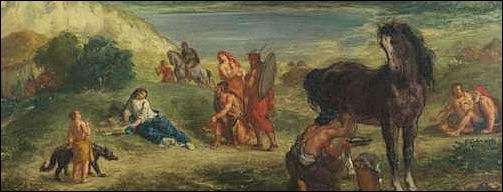

Ovid_among the Scythians

The mummy’s facial features were destroyed. But in this instance — unlike the case of the wounded warrior skeleton — the destruction was inflicted by nature. When the ice lens formed under the burial chamber, it expanded upward. “The extent of the ice was so high, the body was pressed against the logs on the ceiling and smashed,” Schultz says. The skull shattered, making facial reconstruction impossible. His chest, too, was crushed. Still, a lot can be learned. “You can establish a kind of biography from the body,” Schultz says.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, Comptom’s Encyclopedia, Lonely Planet Guides, Silk Road Foundation, “The Discoverers “ by Daniel Boorstin; “ History of Arab People “ by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “Islam, a Short History “ by Karen Armstrong (Modern Library, 2000); and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2016