GAUTAMA SIDDHARTHA, THE BUDDHA

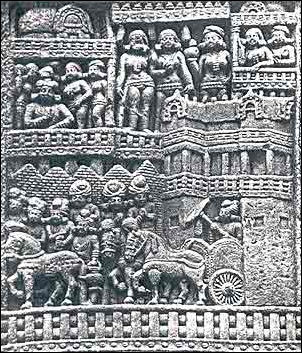

Buddha visiting Kapilavastu

2nd or 1st BCBuddhism began with Gautama Siddhartha (563-480 B.C.), The Buddha. Regarded as both a real-life historical person and religious figure, he was the son of a rich Hindu raja from the Sayka clan and lived 500 years before Jesus Christ and was a contemporary of Confucius, Socrates and Plato. In the centuries after his death fact and myth became intertwined and a legendary Buddha was created. One early Buddhist chant that pays tribute to him goes: “He is indeed the Lord, perfected, whole self-awakened, endowed with knowledge and right conduct, well-farer, knower of the worlds, incomparable charioteer of men to be tamed, teacher of “devas” and mankind.”

According to tradition, the historical Buddha lived from 563 to 483 B.C., although scholars postulate that he may have lived as much as a century later, proposing 565-486 B.C. 463-383 B.C. and 624-544 B.C. and other dates for his life. After years of meditating and wandering, Gautama Siddhartha reportedly became "enlightened" and was recognized as such by others who asked him to guide them to enlightenment. His answers to their questions became the core of Buddhist teachings. In India, by the Pala period (A.D. 700–1200), the Buddha's life was codified into a series of "Eight Great Events". These eight events are, in order of their occurrence in the Buddha's life: 1) his birth, 2) his defeat over Mara and consequent enlightenment, 3) his first sermon at Sarnath, 4) the miracles he performed at Shravasti, 5) his descent from the Heaven of the Thirty-three Gods, 6) his taming of a wild elephant, 7) the monkey's gift of honey, and 8) his death.

Based on the number of books written about him (2,446 in 1999 in the Library of Congress collection), Buddha is the world's 12th most famous person. He ranks behind Jesus and Plato but ahead of Freud and Mozart. The story of Buddha’s life is based in historical fact, legends and poetry. Perry Garfinkel wrote in National Geographic: “The Buddha did not intend his ideas to become a religion; in fact, he discouraged following any path or advice without testing it personally. His dying words, as it's told, were: "You must each be a lamp unto yourselves." Nonetheless, within several hundred years of his death, the Buddha's teachings had taken strong hold [Source: Perry Garfinkel, National Geographic, December 2005]

Websites and Resources on Buddhism: Buddha Net buddhanet.net/e-learning/basic-guide ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Internet Sacred Texts Archive sacred-texts.com/bud/index ; Introduction to Buddhism webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/buddhaintro ; Early Buddhist texts, translations, and parallels, SuttaCentral suttacentral.net ; East Asian Buddhist Studies: A Reference Guide, UCLA web.archive.org ; View on Buddhism viewonbuddhism.org ; Tricycle: The Buddhist Review tricycle.org ; BBC - Religion: Buddhism bbc.co.uk/religion ; A sketch of the Buddha's Life accesstoinsight.org ; What Was The Buddha Like? by Ven S. Dhammika buddhanet.net ; Jataka Tales (Stories About Buddha) sacred-texts.com ; Illustrated Jataka Tales and Buddhist stories ignca.nic.in/jatak ; Buddhist Tales buddhanet.net ; Arahants, Buddhas and Bodhisattvas by Bhikkhu Bodhi accesstoinsight.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“The Life of the Buddha: According to the Pali Canon” by ven Bhikkhu Ñanamoli Amazon.com ;

“Siddhartha” by Herman Hesse. Amazon.com

“Twenty Jataka Tales” (Illustrated) by Noor Inayat Khan H. Willebeek Le Mair Amazon.com ;

“Jataka Tales” (audiobook) narrated by Ellen Burstyn

Amazon.com ;

“Buddha Stories” by Demi (1997) Amazon.com

“Buddhist Scriptures” by Donald Lopez (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com ;

“What the Buddha Taught” by Walpola Rahula Amazon.com ;

“In the Buddha's Words: Anthology of Discourses from the Pali Canon” with Bhikkhu Bodhi, the Dalai Lama Amazon.com ;

“The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching” by Thich Nhat Hanh Amazon.com ;

“Mindfulness in Plain English Paperback” by Bhante Bhante Gunaratana (Author) Amazon.com ;

“Why Buddhism is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment”

by Robert Wright Amazon.com ;

“Buddhism” by Madhu Bazaz Wangu (1993 Amazon.com ;

“Buddhism Plain and Simple”

by Steve Hagen Amazon.com ;

“Little Buddha” (Film) Amazon.com

See Separate Article ANCIENT INDIA IN THE TIME OF THE BUDDHA factsanddetails.com

Was The Buddha a Real Person

Nagaerapata (Chinese) worshopping Buddha Bharhut,early 1st century BC

Most scholars believe that The Buddha — Siddhartha Gautama — was a real person but are reluctant to make claims beyond that he is thought to have taught and founded a monastic order during the Mahajanapada (the Period of the 16 kingdoms that existed in ancient India from the 6th century to 4th century B.C. Bimbisara — his friend, protector, and ruler of the Magadha empire — is believed to be a real person but this is based more on Jain and Buddhist traditions rather than hard evidence. He is said to have been the King of Magadha from 543 to 492 B.C. or 457 to 405 B.C.. The Buddha is said to have died during the early years of the reign of Ajatashatru (Bimbisara’s successor). In 1996, a team of archaeologists discovered a marker honoring the Buddha's birthplace set the by the emperor Ashoka in 250 B.C. [Source: Wikipedia]

There is little agreement among scholars on the veracity of many details in the traditional biographies of The Buddha’s life as "Buddhist scholars...have mostly given up trying to understand the historical person." The earliest versions of Buddhist biographical had many magical, supernatural, mythical and legendary elements. In the 19th century some scholars simply omitted these elements from accounts of The Buddha’s life, giving the impression he was a rational, relatively normal — possibly charismatic or great — teacher.

Buddhist texts present two chronologies which have been used to date the lifetime of the Buddha. The "long chronology", from Sri Lankese chronicles, states the Buddha was born 298 years before Asoka's coronation, making the Buddha's lifespan as 624 to 544 B.C. The "short chronology", from Indian sources and their Chinese and Tibetan translations, place the Buddha's birth at 180 years before Asoka's coronation and death 100 years before the coronation, making the Buddha's lifespan, from as 448 to 368 B.C.. Most historians in the early 20th century use the earlier dates of 563 – 483 B.C. based on Greek evidence. The dating of Bimbisara and Ajatashatru also depends on the long or short chronology.

Biographies and Views of The Buddha

Reconstructing the precise details of the Buddha's life and teachings accurately has been a challenging task. The earliest biographies of the Buddha were not written until centuries after his death, making it difficult to determine which aspects of his life are based on historical fact and which are idealized. One has to approach these biographies with a critical eye and consider the cultural and religious context in which they were written. [Source: Joseph W. Williams, International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, 2000s, Encyclopedia.com]

The biographies, which are typically part of the Jataka tales and soaked with legends added later, generally contain: 1) The Story Of Sumedha, about one of the Buddha’s earlier lives; 2) The Birth Of The Buddha; 3) The Attainment Of Buddhaship, about his enlightenment; 4) First Events After The Attainment; 5) The Buddha's Daily Habits; and 6) The Death Of The Buddha. [Source: Internet History Sourcebooks Project]

One of the most important biographical accounts of the Buddha's life, the Buddhacarita, also the first complete biography of the Buddha; was written by Asvaghosa in the A.D. 2nd century).

Theravada Buddhists tend to see The Buddha as a historical figure who truly underwent an Enlightenment. Mahayana Buddhists tend see him as more metaphysical being summed by the doctrine of the Three Bodies Buddha: 1) the fictitious, conjured up body; 2) the communal body; and 3) a Dharma (teaching) body. On the issue of his identity, the Buddha himself one said: “What was to be known is known by me...What is to be cast out is cast out by me, therefore am I Buddha.”

Some see the Buddha as a practical philosopher who concluded that the ego is a source of suffering and developed a series of techniques to make individuals more self aware and move beyond their existence in the direction of nirvana. In “The End of Suffering: The Buddha in the World”, journalist Pankaj Mishra wrote: “It was the Buddha’s achievement as it was that of Socrates, to detach wisdom from its basics in fixed and often esoteric forms of knowledge and opinion and offer it as a moral and spiritual project for individuals.”

Buddhist Sources on the Buddha

The Buddha, O king, magnifies not the offering of gifts to himself, but rather to whosoever ... is deserving.—Questions of King Milinda. [Source: “The Essence of Buddhism” Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius, 1922, Project Gutenberg]

If you desire to honor Buddha, follow the example of his patience and long-suffering.—Fo-sho-hing-tsan-king. Radiant with heavenly pity, lost in care For those he knew not, save as fellow-lives. —Sir Edwin Arnold.

Who that hears of him, but yearns with love?—Fo-sho-hing-tsan-king.

The Buddha has mercy even on the meanest thing.—Cullavagga.

The words of Buddha, even when stern, yet ... as full of pity as the words of a father to his children.—Questions of King Milinda.

The Royal Prince, perceiving the tired oxen, ... the men toiling beneath the midday sun, and the birds devouring the hapless insects, his heart was filled with grief, as a man would feel upon seeing his own household bound in fetters: thus was he touched with sorrow for the whole family of sentient creatures—Fo-pen-hing-tsih-king.

Ofttimes while he mused—as motionless As the fixed rock his seat—the squirrel leaped Upon his knee, the timid quail led forth Her brood between his feet, and blue doves pecked The rice-grains from the bowl beside his hand. —Sir Edwin Arnold.

Religion During the Time of Buddha

Buddhism originated in northeast India in the 6th and 5th centuries B.C. at a time when the local religion was Brahmanism, the predecessor of Hinduism. Brahmanism was dominated by Brahman priests who presided over rituals and sometimes practiced asceticism. Many of the ascetic Brahmin believed in a concept of the universe known as “brahman” and a similar concept of the human mind, known as “atman”. and thought it was possible to achieve liberation from the cycle of death and rebirth by achieving oneness with the atman. These concepts became cornerstones of Buddhism

The 6th, 5th and 4th centuries B.C. were a time of worldwide political upheaval and intellectual blossoming. It was an age of great thinkers, such as Socrates and Plato in Greece, and Confucius and Laozi in China. In India, Hinduism and animist beliefs are thought to have been the dominate forms of religion. At the time when The Buddha was born there was a great spiritual revolution in India, and many young men left their homes to take up an ascetic life of celibacy and holiness.

This period of time in India was also a time of curiosity, tolerance, and experimentation. Religious scholars and intellectuals speculated about things like the existence of other worlds, the finiteness or the infinity of the universe and whether existence was dominated by is or is not. The conditions were ripe for people to throw out traditional beliefs and accept new ones. A number of movements and leaders appeared. Their success often seemed based on their political skill, and their ability to organize and consolidate their followers with a simple, easy-to-embrace message.

There were a great many holy men and women wandering about. Some were hermits who lived in the forest or jungle. Others were ascetics who practiced various forms of austerities and offered sacrifices to things like fire and the moon. There were also charismatic leaders and sects of movements of various kinds and sizes. Early Buddhist texts counted 62 “heretical” sects. Among these were the Jains, the Naked Ascetics, the Eel-Wrigglers, and the Hair-Blanket sect. The Buddha’s greatest rivals were Nataputa, leader the Jains, and Makkhali Godla, the leader of the Naked Ascetics.

Buddhism was influenced a great deal by Hinduism and the other sects. It adopted Hindu beliefs about karma and reincarnation; followed Jain and traditional Indian views about not destroying life forms; and copied forms of organization for other sects for monks communities. The Buddha himself was like an ascetic Brahmin but was regarded as a heretic among Hindus because he emphasized the impermanent and transitory nature of things, which contradicted the Hindu belief in “Paramatman” (the eternal, blissful self).

Buddha and Hinduism

Jayaram V, a leading author of Indian religions, wrote in Hinduwebsite.com: “Prior to his enlightenment, the Buddha was brought up in a traditional Hindu family. Before finding his own path, he went to Hindu gurus to find an answer to the problem of suffering. He followed the meditation techniques and ascetic practices as prescribed by the Hindu scriptures and followed by the Hindu yogis of his time. It is said that after becoming the Buddha, he showed special consideration to the higher caste Hindus especially the Brahmins (priests) and Kshatriyas (warriors). He exhorted his disciples to treat especially Brahmins with respect and consideration because of their spiritual bent of mind and inner progress achieved during their previous births. It is said that certain categories of Brahmins had free access to the Buddha and that some of the Brahmin ascetics were admitted into the monastic discipline without being subjected to the rigors of probation which was other wise compulsory for all classes of people. The Buddha converted many Brahmins to Buddhism and consider their involvement a sure sign of progress and popularity of his fledgling movement. Much later, we find a similar echo of sentiment in the inscriptions of King Ashoka where he exhorted the people of his empire to show due respect to the Brahmins. [Source: Jayaram V, Hinduwebsite.com |*|]

Buddha and Hindu gods at Ellorca Caves

“The Buddha was not the first teacher in ancient India to contemplate upon suffering and find solutions to remedy it. It has been part of a long tradition in the subcontinent, starting with the Vedic sages and the Jain Tirthankaras who lived at least a thousand years or so before him. The growth of cities in the plains of India along river banks, famines, pandemics, epidemics and natural calamities, and frequent warfare among neighboring kingdoms must have made people acutely aware of the nature of suffering and occupied the minds of scholars and philosophers. |*|

“The Buddha continued the tradition at a time when India was teeming with scores of ascetic movements and teacher traditions. He was also not the first to find a link between desire and suffering. The ascetic and renunciant traditions that preceded him also considered desire as the root cause of suffering. It is also difficult to believe that the Buddha had the first glimpse of suffering only when he went out into the streets. As a prince and as the designated successor to his father's kingdom, he must have had formal education and interacted with several teachers and spiritual masters as he grow up. The knowledge he gathered and the experiences he had in the public must have triggered in him the resolve to find a solution to the problem of suffering.” |*|

See Separate Article: BUDDHISM AND HINDUISM factsanddetails.com

Buddha and Mahavira, the Founder of Jainism

The Buddha lived around the same time and was similar to Vardhamana Mahavira (599 and 527 B.C.), the founder of Jainism and the prophet and prince of the Jains. He is mentioned in Buddhist scripture as the “Naked Ascetic” and was a contemporary of Confucius in China and Jeremiah, Ezekiel and Isaiah in Israel and Aristotle and Plato in Greece. Like Buddha he forsook his life of wealth and privilege for a spiritual life, and rejected the sacrificial rites of the Hindus and the caste system. Vardhaman. Mahavira means “great hero.”

Alfred J. Andrea wrote: “Many parallels exist between the legendary lives of the Mahavira (the founder of the Indian philsophy of Jainism) and the Buddha, and several of their teachings are strikingly similar. Each rejected the special sanctity of (the Old Indian) Vedic literature, and each denied the meaningfulness of caste distinctions and duties. Yet a close investigation of their doctrines reveal substantial differences. [Source: Alfred J. Andrea and James H. Overfield, The Human Record: Sources of Global History, Vol 1, 2d. ed., (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1994), pp. 72-74]

Like the Mahavira, young Prince Siddhartha Gautama, shrinking in horror at the many manifestations of misery in this world, fled his comfortable life and eventually became an ascetic. Where, however, the Mahavira found victory over karma in severe self-denial and total nonviolence, Prince Gautama found only severe disquiet. The ascetic life offered him no enlightenment as to how one might escape the sorrows of mortal existence. After abandoning extreme asceticism in favor of the Middle Path of self-restraint, Gautama achieved Enlightenment in a flash while meditating under a sacred pipal tree. He was now the Buddha.

Jain statues in Gwailior

Arhants (Buddha's Disciples)

The first Buddhist monks were called “arhants” . They were regarded as men well on their way down the path to seeking nirvana. One passage from an early Buddhist text goes: “Ah, happy indeed the Arhants! In them no craving’s found. The “I am” conceit is rooted out; confusion’s net is burst. Lust-free they have attained; translucent is the mind of them. Unspotted in the world are they...all cankers gone.”

The first five ascetics who became the first monks under The Buddha were joined by 55 others. They together with The Buddha are known as the 61 arhants. The were ordained by The Buddha by repeating the simple phrase: “Come monk; well-taught in the Dharma; fare the attainment of knowledge for making a complete anguish.” Others that came later were ordained after cutting their hair and beard, donning a robe and uttering three times: “I go to The Buddha for refuge, I go to Dharma for refuge, I go to the sangha for refuge.” This ritual remains the basis of the Theravada monk ordination process today.

Aanada was The Buddha constant companion. His two chief disciples’sariputta and Moggallana — were two ascetics who for were known for seeking the Dharma to deathlessness Mahkaccan was ranked the highest for his ability to interpret the Buddha’s brief statements. Buddha instructed his disciples on methods that could be used to discover the eternal truth.

Find Suggests Buddha Lived in 6th Century B.C.

In November 2013, AFP reported: “The discovery of a previously unknown wooden structure at the place of the Buddha’s birth suggests the sage might have lived in the 6th century B.C. — two centuries earlier than thought — archeologists said. Traces of what appears to have been an ancient timber shrine were found under a brick temple that is itself within Buddhism’s sacred Maya Devi Temple at Lumbini, southern Nepal, near the Indian border. In design it resembles the Asokan temple erected on top of it. Significantly, however, it features an open area, unprotected from the elements, from which it seems a tree once grew — possibly the tree under which the Buddha was born. “This sheds light on a very very long debate” over when the Buddha was born and, in turn, when the faith that grew out of his teachings took root, archaeologist Robin Coningham said. [Source: AFP-Jiji, November 26, 2013]

It’s widely accepted that the Buddha was born beneath a hardwood sal tree at Lumbini as his mother, Queen Maya Devi, the wife of a clan chief, was traveling to her father’s kingdom to give birth. But much of what is known about his life and time has its origins in oral tradition — with little scientific evidence to sort out fact from myth. Many scholars contend that the Buddha — who renounced material wealth to embrace and preach a life of enlightenment — lived and taught in the 4th century B.C., dying at around the age of 80. “What our work has demonstrated is that we have this shrine (at Buddha’s birthplace) established in the 6th century B.C.” that supports the hypothesis that the Buddha might have lived and taught in that earlier era, Coningham said.

ruins within Maya Devi Temple in Lumbini

Radiocarbon and optically stimulated luminescence techniques were used to date fragments of charcoal and grains of sand found at the site. Geoarchaeological research meanwhile confirmed the existence of tree roots within the temple’s central open area. The team’s peer-reviewed findings appear in the December issue of the journal Antiquity, ahead of the 17th congress of the International Association of Buddhist Studies in Vienna in August next year.

Lumbini was overgrown by jungle before its rediscovery in 1896. Since it’s a working temple, the archeologists found themselves digging in the midst of meditating monks, nuns and pilgrims. It’s not unusual in history for adherents of one faith to have built a place of worship atop the ruins of a venue connected with another religion. But what makes Lumbini special, Coningham said, is how the design of the wooden shrine resembles that of the multiple structures built over it over time. Equally significant is what the archaeologists did not find: signs of any dramatic change in which the site has been used over the ages. “This is one of those rare occasions when belief, tradition, archaeology and science actually come together,” he said.

Kings in the Monarchical States of The Buddha’s Time

Educated at Taxila, Pasenadi was a large-hearted ruler. He gave lands on the royal domains to the Hindus, and also donated groves and built monasteries for the Buddhist monks. His relations with the Buddha were specially cordial, and he often used to visit him and seek his advice in difficulties. Once Pasenadi expressed amazement at the way the great Teacher maintained peace within the Order (Samgha), whereas the former was sorely troubled by the depredations of robbers, like Angulimala, and by the machinations of his family and ministers. Indeed, Pasenadi lost his throne on account of the revolt of his son, Vidudabha (Viruddhaka), instigated by the minister DIgha-Carayana. Pasenadi invoked Ajatasatru’s aid, but before entering Rajagriha the Kosala king died of fatigue and anxiety at its gates. AjataSatru honoured him by a state-funeral, and wisely left Vidudabha undisturbed.

Vidudabha’s reign is darkened by the terrible atrocity which he perpetrated on the Sakyas. Apparently he did all that to avenge their treachery in marrying Vasabha-Khattiya, a slave-girl, to his father, but perhaps his real motive in invading the territories of the Sakyas was to destroy their autonomy completely. We do not know anything more about Vidudabha or his successors

Bimbisara

Bimbisara extended his influence in the beginning by a policy of matrimonial alliances. His principal queens were KosaladevI, sister of Pasenadi; Cellana, daughter of the Licchavi prince 'Cetaka; and Ksema, Madra (Central Punjab) princess. These marriages not only show the high position of Bimbisara among his royal contemporaries, but they seem to have also paved the way for the expansion of Magadha. For instance, Ko^ala-devl alone brought as pin-money a part of Kail yielding a revenue of a hundred thousand.

Bimbisara also enlarged his kingdom by his military skill. We learn that after defeating Brahmadatta, he boldly annexed Ariga, which roughly corresponded to modern Monghyr and Bhagalpur districts. That other territories were absorbed into Magadha during the reign of Bimbisara is further clear from the estimate of its size given by the Pall commentator Buddhaghosa, according to whom it had almost doubled itself during the interval between the Buddha and Bimbisara’s successor. The government was well organised, and the activities of the high officers of the realm, called Mahamattas (Mahamattas), were strictly watched and controlled. The administration of criminal law was also severe.

Bimbisara cultivated friendly relations with distant states, for he is said to have received an embassy from a king of Gandhara, named Pukkusati. Incidentally it shows that Bimbisara must have flourished when Gandhara was still an independent kingdom, i.e., prior to the Achtemenid conquest about 516 B.C. We can arrive at a closer approximation to truth by another method. According to the Ceylonese chronicles Bimbisara’s reign lasted 5 a years, and Ajatasatru had ruled for 8 years at the time of the Buddha’s death, which has been fixed by Geiger and other scholars in 483 B.C. Add to this sixty years (52-I-8), and we get 543-44 B.C. as the date of Bimbisara’s accession to the throne. He was a patron of the Buddha from the very start of the latter’s career, and as a mark of good-will Bimbisara presented the famous Bamboo grove (Karanda-Venu-vana) to the Samgha. He also fed monks and exempted them from paying fares and ferry dues. But Bimbisara made endowments in favour of other sects as well, and we cannot, therefore, be sure how far he progressed along the path. Indeed, the Uttarajjhajana (Uttaradbyayana) Sutra and other Jain works even represent him as a devotee of Mahavlra and having faith in his Law.

Ajdtaiatru

Bimbisara was succeeded by his son Ajatasatru, also called Kunika, about the year 491 B.C. The latter was at first his father’s viceroy at Campa, the capital of Anga, where he learned the art of government. Tradition says that at the instigation of Devadatta, a cousin of the Buddha and his rival to the leadership of the Samgha, AjataSatru imprisoned his father and starved him to death. It is difficult to accept this story literally, but what appears probable is that Bimbisata’s end was tragic and perhaps due to foul play. Afterwards, AjataSatru is represented in the Samannaphala-Sutta as having expressed remorse to the Buddha for his heinous crime, and the great Teacher felt impressed by his penitence and exhorted him to “go and sin no more.” AjataSatru’s visit to the Buddha is also depicted in one of the Bharhut sculptures of about the middle of the second century B.C. [Source: “History of Ancient India” by Rama Shankar Tripathi, Professor of Ancient Indian History and Culture, Benares Hindu University, 1942]

The manner of her husband’s death gave such a tremendous shock to KoSaladevI that she too died of grief. Pasenadi immediately confiscated the revenues of the Kasi estate, which had been settled on her as ‘pin-money’, and this resulted in hostilities between him and Ajatasatru. The duel was a prolonged affair, fortune favouring each combatant alternately. At last, they came to terms, and the Magadhan monarch got not only the disputed township of Kail, but also the hand of Pasenadi’s daughter, Vajira. Henceforth Ka§i was permanently absorbed into the kingdom of Magadha.

The next important event in AjataSatru’s reign was his conflict with the Licchavis. Traditions differ regarding its cause. Any of these — Cetaka’s refusal to surrender AjataSatru’s half-brothers, Halla and Vehalla, who had taken shelter in VaiSall with certain prized objects, or an alleged treachery on the part of the Licchavis concerning a mine of gems — may have provoked war. But the real motive appears to have been the destruction of the power of the neighbouring oligarchy, which was without doubt a thorn in the side of an ambitious potentate. Ajatasatru took all possible precautions to ensure victory. He sent his trusted ministers, Sunidha and Vassakara, to sow dissensions among the Licchavi chiefs. He organised his army carefully, and equipped it with powerful and destructive weapons. The war, though long and sanguinary, ended in favour of Ajatasatru, and the Licchavi territories passed under his rule. Perhaps after the conquest of Vaisall, he carried his arms further northward, and the regions up to the mountains accepted submission to him. Thus the annexation of Ahga, Kasi, VaiSall, and other surrounding lands made Magadha the mightiest kingdom in Northern India. It naturally aroused the jealousy of Avanti, and although we hear of AjataSatru fortifying his capital in anticipation of Pradyota’s invasion, we do not know if it ever materialised in his time. According to Pali works, AjataSatru’s reign lasted 32 years, but the Puranas give 27 years only as its duration. The Jain works testify that he was a follower of their faith, but the Buddhist texts would have us believe that in his later days Ajatasatru did honour to the Buddha and found solace in his ethical teachings. Thus, it was due to his regard for the Buddha that Ajatasatru claimed a share of his relics, and enshrined them in a Stupa.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: East Asia History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu , “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org, Asia for Educators, Columbia University; Asia Society Museum “The Essence of Buddhism” Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius, 1922, Project Gutenberg, Virtual Library Sri Lanka; “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World's Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures: Volume 5 East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1993); BBC, Wikipedia, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2024