BUDDHISM

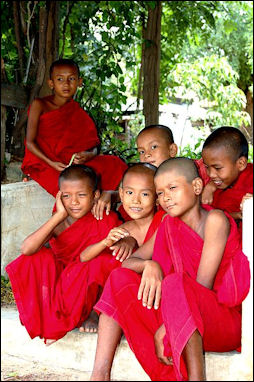

Young Theravada Buddhist

monks in Myanmar Buddhism is the name given relatively recently by Westerners to a vast and diverse body of beliefs and practices attributed to Gautama Siddhartha (563–483 B.C.), an Indian prince who renounced worldly pursuits and attained enlightenment beneath a banyan tree, thus becoming the "enlightened one", or The Buddha. In the Buddha’s time his teachings were known as Dharma (Dhamma), meaning "what is right and what ought to be.” For many centuries Buddhism was a code adopted by people of a variety of religious beliefs. The Buddha was more of a social philosopher than a religious leader. As time went on Gautama Siddhartha was deified into The Buddha and miraculous powers were attributed to him.

The Buddha taught that a person could escape the suffering of the world by eliminating desire. The way of living he established is also considered to be a philosophy to gain a better understanding of values and reality. Joshua Hammer wrote in Smithsonian magazine, Buddhism Is a belief system that "holds that satisfactions are transitory, life is filled with suffering, and the only way to escape the eternal cycle of birth and rebirth—determined by karma, or actions—is to follow what is known as the Noble Eightfold Path, with an emphasis on rightful intention, effort, mindfulness and concentration. Buddhism stresses reverence for the Buddha, his teachings (Dhamma) and the monks (Sangha)—and esteems selflessness and good works, or “making merit.” At the heart of it is vipassana meditation, introduced by the Buddha himself. Behind vipassana lies the concept that all human beings are sleepwalking through life, their days passing by them in a blur. Only by slowing down, and concentrating on sensory stimuli alone, can one grasp how the mind works and reach a state of total awareness." [Source: Joshua Hammer, Smithsonian magazine, September 2012]

Buddhism has been called the world's oldest missionary religion. Since its beginnings it has spread to nearly every part of the world and is the main belief in many parts of Asia. As it spread, its original teaching assimilated new values and ideas and underwent major changes in doctrinal and institutional principles. This explains why Buddhism encompasses such huge variety of beliefs and practices. There is no central Buddhist organization, single authoritative text, or simple set of defining practices. Despite its incredible diversity, though, there are elements of Buddhism that most followers hold dear such as the recitation of the Three Refuges (also known as the Triple Gem): "I go for refuge to the Buddha, I go for refuge to the dharma, I go for refuge to the sangha." Sangha refers to community of Buddhist monks. [Source: Jacob Kinnard, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2018, Encyclopedia.com]

Websites and Resources on Buddhism: Buddha Net buddhanet.net/e-learning/basic-guide ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Internet Sacred Texts Archive sacred-texts.com/bud/index ; Introduction to Buddhism webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/buddhaintro ; Early Buddhist texts, translations, and parallels, SuttaCentral suttacentral.net ; East Asian Buddhist Studies: A Reference Guide, UCLA web.archive.org ; View on Buddhism viewonbuddhism.org ; Tricycle: The Buddhist Review tricycle.org ; BBC - Religion: Buddhism bbc.co.uk/religion ; A sketch of the Buddha's Life accesstoinsight.org ; What Was The Buddha Like? by Ven S. Dhammika buddhanet.net ; Jataka Tales (Stories About Buddha) sacred-texts.com ; Illustrated Jataka Tales and Buddhist stories ignca.nic.in/jatak ; Buddhist Tales buddhanet.net ; Arahants, Buddhas and Bodhisattvas by Bhikkhu Bodhi accesstoinsight.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Buddhist Scriptures” by Donald Lopez (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com ;

“What the Buddha Taught” by Walpola Rahula Amazon.com ;

“In the Buddha's Words: Anthology of Discourses from the Pali Canon” with Bhikkhu Bodhi, the Dalai Lama Amazon.com ;

“The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching” by Thich Nhat Hanh Amazon.com ;

“Mindfulness in Plain English Paperback” by Bhante Bhante Gunaratana (Author) Amazon.com ;

“Why Buddhism is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment”

by Robert Wright Amazon.com ;

“Buddhism” by Madhu Bazaz Wangu (1993 Amazon.com ;

“Buddhism Plain and Simple”

by Steve Hagen Amazon.com ;

“Little Buddha” (Film) Amazon.com

“The Life of the Buddha: According to the Pali Canon” by ven Bhikkhu Ñanamoli Amazon.com ;

“Siddhartha” by Herman Hesse. Amazon.com

“Twenty Jataka Tales” (Illustrated) by Noor Inayat Khan H. Willebeek Le Mair Amazon.com ;

“Jataka Tales” (audiobook) narrated by Ellen Burstyn

Amazon.com ;

“Buddha Stories” by Demi (1997) Amazon.com

Buddhism's Success

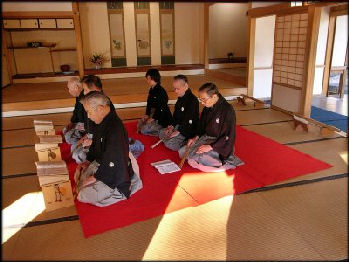

Mahayana Buddhist monks

chanting in JapanBuddhism’s success in attracting believers has been at least partly attributed to the universality of its ethical teaching and the flexibility of its spiritual message. The goal of Buddhism is to reach a transcendent state that completely absorbs the mind and soul and makes the material world meaningless, bringing freedom and peace to the individual worshiper. It also promotes a code of conduct for the community and the individual that provides a framework for a peaceful society and peace of mind.

It can be argued that Buddhism is a more tolerant and peaceful religion than other major religions such as Islam, Judaism or Christianity. Buddhist sects have had periods of conflict, but rarely engaged in wars of conquest, Inquisitions, pogroms or persecution. Today it is not uncommon for Buddhists of different sects to pray and meditate under the same roof. Buddhism though is not violence free . In medieval Japan, rival Buddhist sects lived in fortified monasteries and had their own monk armies. In Sri Lanka, the war between the Buddhist majority and a Hindu minority has at times been quite brutal and nasty.

On the success of Buddhism, Prof. Max Mueller, a German philosopher and influential post-World War II Catholic intellectual, wrote: "To my mind...Buddhism has always seemed to be not a new religion, but a natural development of the Indian mind in its various manifestations, religious, philosophical, social and political." Jayaram V, an expert of Indian religions, said, "The Buddha reset the native thinking and breathed fresh life into certain ancient beliefs providing them with a new perspective and interpretation that was indisputably a product of human intellect with its roots firmly entrenched in virtue and righteous conduct.”

Buddhism Organization and Membership

There is no central Buddhist organization, single authoritative text, or simple set of defining practices. Sangha refers to community of Buddhist monks. There are tow main types of Buddhists monks in the Sangha and lay people. There are three main Buddhist schools (sects): 1) Theravada Buddhism, 2) Mahayana Buddhism, and 3) Vajrayana (Tibetan Buddhism) (See Below. [Source: Jacob Kinnard, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2018, Encyclopedia.com]

Theravada Buddhism traditionally has not had an overarching theocratic structure like the Vatican nor are No1 leader like the Pope or Dalai Lama. Each country where Theravada Buddhism where is found has its own organization that does not extend beyond the national level. Thailand's chief Buddhist monk is known as the Supreme Patriarch.

Jacob Kinnard wrote in the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: The fundamental structure of Buddhism is that it is a self-governing body of individuals, each of whom is theoretically equal and intent on his or her own salvation while compassionately mindful of fellow beings. As soon as Buddhist monks began to form into groups, however, there was a need for rules (contained in the Vinaya Pitaka) and also for a degree of hierarchy that was needed to keep order, to enforce the rules, and to maintain religious purity within the community. This hierarchy was, and continues to be, based on seniority — the longer one has been a monk, the more seniority he or she has. There is thus no single authority in the Buddhist world. Rather, each school has a leader or group of leaders who provide guidance to the community as a whole, and the degree of internal hierarchy varies considerably from school to school and country to country. [Source: Jacob Kinnard, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2018, Encyclopedia.com]

The Buddha stressed several key issues with regard to membership within the Buddhist tradition. 1) Buddhism was open to anyone, regardless of social status or gender (this would later become an issue within the sangha, however, as women were excluded in at least some Buddhist schools); and 2) becoming a Buddhist was an entirely self-motivated act. In a sense the Buddha and his early followers did engage in missionizing activities, but they did so not so much to gain converts to their new religion as to share the dharma out of compassion, out of an attempt to alleviate the suffering (duhka).

Buddhists

Buddhists account for 6 percent to 8 percent of the world's total population. Buddhism is practiced by around a half billion people (488 million according to Pew in 2012; 520 according to Wikipedia in 2023, or 535 million according to the Chinese government in 2016). Buddhism had around 379 million followers (6 percent of the world’s population) in the early 2000 according to National Geographic.[Source: Wikipedia]

Buddhism is the world's fourth, fifth or sixth largest religion in world behind Christianity, Islam and Hinduism. Traditional Chinese religions has a similar number of adherents as Buddhism. Some surveys include non-religious and atheist people as a a religious group. Many practitioners of Buddhism and Chinese folk religions are only luke-warm practitioners. These are among the reason for the discrepancies and ranking differences.

World religions (percent of the world population): 1) Christianity (31.6 percent); 2) Islam (25.8 percent); 3) Hinduism (15 percent); 4) non-religious and atheist (14.4 percent); 5) Chinese folk religions (6 percent); 6) Buddhism (6 percent); and 7) Other (1 percent). [Source: Statista]

See Separate Article: BUDDHISTS factsanddetails.com

Buddhism — a Religion, Moral Code, Philosophy or Psychology?

Tibetan monks debating

Even today some scholars insist that Buddhism is not a religion because it is not focused on a god or godhead and does not prepare individuals for the afterlife but rather is "a system of morality and philosophy based on the belief that life is too full of suffering to be worth living” and is a “discipline for governing man’s attitude for the here and now, the present conditions, and, if properly and diligently carried out, will lead gradually but surely to what is best, the highest good.”

According to the Asia Society Museum: “Buddhism is a religion that... offers a spiritual path for transcending the suffering of existence and the cycle of rebirth. Release from this endless cycle is achieved only by attaining enlightenment, the goal for which Buddhists strive. According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Buddhism is a philosophical and ethical system with the Buddha as its greatly revered founder. Guided by the Middle Path, which rejects both luxury and asceticism, Buddhism proposes a life of good thoughts, good intentions, and straight living, all with the ultimate aim of achieving nirvana, release from earthly existence. For most beings, nirvana lies in the distant future, because Buddhism, like other faiths that originated in India, believes in a cycle of rebirth. Humans are born many times on earth, each time with the opportunity to perfect themselves further. And it is their own karma-the sum total of deeds, good and bad-that determines the circumstances of a future birth. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art]

According to the BBC: “Buddhism is a spiritual tradition that focuses on personal spiritual development and the attainment of a deep insight into the true nature of life. Buddhists seek to reach a state of nirvana, following the path of the Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama. The history of Buddhism is the story of one man's spiritual journey to enlightenment, and of the teachings and ways of living that developed from it. There is no belief in a personal god. Buddhists believe that nothing is fixed or permanent and that change is always possible. The path to Enlightenment is through the practice and development of morality, meditation and wisdom. Buddhists believe that life is both endless and subject to impermanence, suffering and uncertainty. These states are called the tilakhana, or the three signs of existence. Existence is endless because individuals are reincarnated over and over again, experiencing suffering throughout many lives. It is impermanent because no state, good or bad, lasts forever. Our mistaken belief that things can last is a chief cause of suffering.” [Source: BBC]

On Buddhism as a Religion, Piyadassi Thera, a Sri Lanka monk who studied at Harvard, wrote: “To all Buddhists the question of religion and its origin, is not a metaphysical one. But a philosophical and an intellectual one. Religion is no real creed or a code of revelation or fear of the unknown fear of a supernatural being who rewards and punishes his good deeds and ill deeds. In other words it is not a theological concern. But rather a philosophical and an intellectual concern resulting from the experience of suffering, conflicts, unsatisfactoriness of the empirical existence of the nature of life. The Buddhist way of life is an intensed process of cleansing one's speech action and thought. It is self development and self-purification resulting in self-realization. The emphasis is on practical results and not on mere philosophical speculation or logical abstraction or even mere cogitation.

“Buddhism as a Philosophy: From the point of view of philosophy, Buddha was not concerned with the problems that have worried philosophers both of the East and West from the beginning of history. He was not concerned with metaphysical problems which only confused man and upset his mental equilibrium. Their solution he knew will not free mankind from suffering from the unsatisfactory nature of life. That was why the Buddha hesitated to answer such questions as "Is the world eternal or not ?" "Has the world an end or not?" What is the origin of the world?" So on and so forth.

“Buddhism as a Psychology: Buddhism also is the most psychological of religions. It is significant that the intricate workings of the human mind are more fully dealt with in Buddhism rather than in any other religion and therefore psychology works hand in hand with Buddhism than with any other religion. Is Buddhism related to modern psychology ? one may ask. Yes, but with some differences. Buddhism is more concerned with the curative rather than the analysis. Psychology helps us to understand life intellectualy. Meditation goes beyond the intellect to the actual experience of life itself. Through Meditation the Buddha had discovered the deeper universal melodies of the human heart and mind.

Buddhist expansion

Important Buddhist Terms

Arhat — worthy one, the name used for The Buddha’s earliest disciples

Bhikkhu — monk, used most commonly in Theravada Buddhism

Bhikkhuni — female monk

Bodhi — enlightenment; awakening, in reference to the bodhi tree that The Buddha was sitting under when he achieved enlightenment

Bodhisattva — A person who has attained enlightenment but, rather than entering a state of nirvana, chooses to stay behind to help others reach enlightenment and works for the welfare of all those still caught in samsara

Buddha — A spiritual leader who has reached full enlightenment.

The Buddha — The title of Siddhartha Gautama after he attained enlightenment.

[Source: Jacob Kinnard, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2018, Wikipedia, Encyclopedia.com]

Ch'an (Zen in Japan) — a school of Mahayana Buddhism

Dana — proper giving; generosity

Deva — deity; divine being; divine

Dharma (Pali, dhamma) — the collection of moral laws that govern the universe, used in both Buddhism and Hinduism. In Buddhism it can refer to the teachings of the Buddha. In Hinduism is can refer to order.

Duhkha (Pali, dukkha) — suffering; unsatisfactoriness

Enlightenment — The state of realization and understanding of life, a feeling of unity with all things

Karma — deed; law of cause and effect; result of good or bad actions in this lifetime that can affect this or later lifetimes.

Laity (lay people) — regular people who follow Buddhism, distinct from monks, nuns and clergy who are known as the sangha

Mahayana — one of major schools of Buddhism practiced mainly in China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. It evolved from the Mahasanghika (Great Assembly).

Monastery — A place where religious people such as monks live, away from the world and following strict religious guidelines

Nirvana — (the Sanskrit word literally means "to blow out, to extinguish") means beyond time and space; the end of suffering; the goal of all Buddhists; the absolute elimination of karma; the absence of all states

pancha sila — five ethical precepts; the basic ethical guidelines for the layperson

Prajna — wisdom

Puja — honor; worship

Samsara — the cyclical nature of life and the cosmos; rebirth

Samudaya — arising (of suffering); the second Noble Truth

Sangha — community of monks

Shramana — wanderer

Sila — ethics; morality

Stupas — a structure containing relics such as the remains of a revered Buddhist monks. Oiginally they were mounds marking the spot where the Buddha's ashes were buried.

Theravada — one of two major schools of Buddhism practiced mainly in Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and Thailand. It evolved from the Sthavira (Elders).

Upaya — the concept of skillful means, an important idea in Mahayana Buddhism

Vajrayana (Tibetan Buddhism) — evolved from a fusion of Mahayana Buddhism with mystical Tantric concepts from India

Wheel of the Dharma — visual symbol representing the Buddha's preaching his first sermon and also, with its eight spokes, of Buddhism's Eightfold Path Yogacara, or Consciousness-Only school of Buddhism

Basic Buddhist beliefs

Buddhist Sources on Buddhism and Mankind

O Buddha, the worship of thee consists in doing good to the world.—Bhakti Sataka. [Source:“The Essence of Buddhism” Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius, 1922, Project Gutenberg ]

Should those who are not with us, O Brethren, speak in dispraise of me, or of my doctrine, or of the church, that is no reason why you should give way to anger.—Brahma-jala-sutta.

Buddha, Why should there be such sorrowful contention? You honor what we honor, both alike: then we are brothers as concerns religion.—Fo-sho-hing-tsan-king.

No decrying of other sects, ... no depreciation (of others) without cause, but on the contrary, rendering of honor to other sects for whatever cause honor is due. By so doing, both one's sect will be helped forward, and other sects benefited; by acting otherwise, one's own sect will be destroyed in injuring others.—Rock Inscriptions of Asoka.

Who is a (true) spiritual teacher? He who, having grasped the essence of things, ever seeks to be of use to other beings. —Prasnottaramalika.

Tell him ... I look for no recompense—not even to be born in heaven—but seek ... the benefit of men, to bring back those who have gone astray, to enlighten those living in dismal error, to put away all sources of sorrow and pain from the world.—Fo-pen-hing-tsih-king.

Ye, then, my followers, ... give not way ... to sorrow; ... aim to reach the home where separation cannot come.—Fo-sho-hing-tsan-king.

Because he has pity upon every living creature, therefore is a man called "holy." —Dhammapada. [Source: “The Essence of Buddhism” Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius, 1922, Project Gutenberg]

Let a man say that which is right, not that which is unrighteous, ... that which is pleasing, not that which is unpleasing, ... that which is true, not that which is false.—Subhasita-sutta.

Who, though he be cursed by the world, yet cherishes no ill-will towards it. —Sammaparibbajaniya-sutta. He who holds up a torch to (lighten) mankind is always honored by me.—Rahula-sutta. Born to give joy and bring peace to the world.—Fo-pen-hing-tsih-king.

Then the man ... said to himself: "I will not keep all this treasure to myself; I will share it with others." Upon this he went to king Brahmadatta, and said: ... "Be it known to you I have discovered a treasure, and I wish it to be used for the good of the country."—Fo-pen-hing-tsih-king.

The sorrow of others enters into the hearts of good men as water into the soil.—Story of Haritika.

An example for all the earth.—Fo-sho-hing-tsan-king.

Buddhist Sources on Religion and God

Wherein does religion consist? In (committing) the least possible harm, in (doing) abundance of good, in (the practice of) pity, love, truth, and likewise purity of life.—Pillar Inscriptions of Asoka. [Source: “The Essence of Buddhism” Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius, 1922, Project Gutenberg]

(Not superstitious rites, but) kindness to slaves and servants, reverence towards venerable persons, self-control with respect to living creatures, ... these and similar (virtuous actions are the rites which ought indeed to be performed.)—Rock Inscriptions of Asoka.

The practice of religion involves as a first principle a loving, compassionate heart for all creatures.—Fo-pen-hing-tsih-king.

Shall we in worshipping slay that which hath life? This is like those who practice wisdom, and the way of religious abstraction, but neglect the rules of moral conduct.—Fo-sho-hing-tsan-king.

How can a system requiring the infliction of misery on other beings be called a religious system?... To seek a good by doing an evil is surely no safe plan.—Fo-pen-hing-tsih-king. Unto the dumb lips of his flock he lent Sad pleading words, showing how man, who prays For mercy to the gods, is merciless. —Sir Edwin Arnold.

I then will ask you, if a man, in worshipping ... sacrifices a sheep, and so does well, wherefore not his child, ... and so do better? Surely ... there is no merit in killing a sheep!—Fo-pen-hing-tsih-king. Religion he looks upon as his best ornament.—Fo-sho-hing-tsan-king.

Worship consists in fulfilling the design (of the person honored), not in offerings of perfumes, garlands, and the like.—Jatakamala.

Compassion for all creatures is the true religion.—Buddha-charita.

Religion means self-sacrifice.—Rukemavati.

The acts and the practice of religion, to wit, sympathy, charity, truthfulness, purity, gentleness, kindness.—Pillar Inscriptions of Asoka.

But if others walk not righteously, we ought by righteous dealing to appease them: in this way, ... we cause religion everywhere to take deep hold and abide.—Fo-sho-hing-tsan-king.

The loving Father of all that lives.—Tsing-tu-wan.

Our loving Father, and Father of all that breathes.—Daily Manual of the Shaman.

Even so of all things that have ... life, there is not one that (the Buddhist anchorite) passes over; ... he looks upon all with ... deep-felt love. This, verily, ... is the way to a state of union with God.—Tevijja-sutta.

Dharmachakra, symbol of the eightfold path

Basic Concepts of Buddhism

Buddhists believe that suffering is the central human condition and is caused by desire. Nirvana, or the end of suffering, can be achieved through the right way of acting and thinking in life. The founder of Buddhism, Siddhartha Gautama (also known as the Buddha), describes this in his teachings. According to “The World of Buddhism: Buddhist Monks and Nuns in Society and Culture”: "For the Buddhist, the universe is a place of delusion and suffering, in which living beings — who are, if they but knew it, mere collections of "aggregates", forever fickle and changing — are condemned by their passions [desires] to an endless cycle of rebirths." [Source: Heinz Bechert and Richard Gombrick, eds., The World of Buddhism: Buddhist Monks and Nuns in Society and Culture (Thames and Hudson) 1984, p. 28.]

The basic teaching of the Buddha is called the Dharma, a term that also has other meanings in Buddhist theology. The symbol of the Dharma is a wheel, particularly one with eight spokes. The core of the Dharma consists of two parts: the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path. The Four Noble Truths summarize the Buddha's insight into the nature of reality and human existence.

The Eightfold Path refers to the path of the Buddha's teachings that can lead to the end of suffering and realize the truth. A series of steps traditionally divided into three distinct phases that should be progressively mastered, this path is a systematic and practical way by which a person can retrace the Buddha's own quest for enlightenment. The Eightfold Path comprises 1) right view, 2) right intention, 3) right speech, 4) right conduct, 5) right livelihood, 6) right effort, 7) right mindfulness, and 8) right concentration. This “Middle Path” avoids both the extreme of self-denial and the extreme of self-indulgence and leads an individual to recognize the impermanence of all things.

Four Noble Truths — the doctrinal foundation of Buddhism: that 1) all life is suffering, 2) desire causes suffering, 3) suffering can end, and 4) ending suffering happens by following the path of the Buddha's teachings, the Eightfold Path, mainly through meditation, moral training, and discipline.. "The Four Noble Truths" embodies the essence of the Buddha's teachings. Only by following these teachings can the individual reach enlightenment, or salvation, and, after death, the transcendent state known as nirvana. [Source:: Monks and Merchants, curated by Annette L. Juliano and Judith A. Lerner, November 17, 2001,Asia Society Museum asiasocietymuseum.org ]

Three Refuges, or Triple Gem — 1) the Buddha, 2) the dharma, and 3) the sangha; the taking of the Three Refuges is a basic rite of passage in Buddhism. Tipitaka — The Buddhist sacred texts accepted by all branches of Buddhism. Tripitaka (Pali, tipitaka) means “three baskets”, or “three sets”: It is a collection of the Buddha's teachings — 1) the Vinaya (Discipline), 2) the Dharma (Doctrine), and 3) the Abhidharma (Pali, Abhidhamma), meaning; Advanced Doctrine.

See Separate Article: BUDDHIST BELIEFS factsanddetails.com; BUDDHA'S FIRST SERMON, THE MIDDLE WAY, FOUR NOBLE TRUTHS AND EIGHTFOLD PATH factsanddetails.com

Uniqueness of Buddhism

The Buddha said "Do not believe in anything simply because you have heard it; not in traditions because they have been handed down for many generations; not in anything because it is spoken and rumoured by many; not in anything because it is found written in your spiritual texts; not in anything merely on the authority of your teachers and elders, but only after observation and analysis, when you find that anything agrees with reason and conducive to the good and benefit of one and all, then accept it and live up to it". (Kalama Sutta).

The Sri Lankan monk Aryadasa Ratnasinghe wrote: “Buddhism stands unique since it denies in the existence of a soul (ego). Buddha said that the idea of a soul is an imaginary, false and baseless belief, which has no corresponding reality, but produces harmful thoughts, selfish desire, craving, attachment, hatred, ill-will, conceit, pride, egoism and other defilements, impurities and problems. In short, to this false view can be traced all the evils in the world which we experience. Soul is usually explained as the principle of life, the ultimate identity of a person or the immortal constituent of self.

“Among the founders of world religions, the Buddha was the only teacher who did not claim to be a prophet, or incarnation of a god or a super being above mankind. He was a man pure and simple, and devoted his entire life to holiness. He was a noble prince of the Sakya clan, the only son of king Suddhodana of the ancient Kapilavattu (modern Piprawa on the Nepal border in North India).”

Eight Auspicious Symbols of Tibetan Buddhism: 1) The Endless Knot; 2) The Treasure Vase; 3) The Lotus Flower; 4) Two Golden Fish; 5) The Parasol; 6) The Conch Shell; 7) The Dharma Wheel; 8) The Banner of Victory

Buddhist Emphasis on Suffering

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “The Buddha's most basic insight was consistent with the personal crisis that had led him into the forest: life, which at times seems so full of good things, is actually a process of endless suffering. Even if we are not actually hungry or in pain, even if we live in sumptuous luxury, we actually endure ceaseless emotional hunger and pain. The reason why is that we are creatures of wants: our longings for things or people that will please us and satisfy our needs. The Buddha, through the vision of meditative trance, had become convinced that the world of things is actually illusory, that the beauties of the world are mere mirages that we project upon a meaningless universe of dust. We long for these illusory things, and knowingly or unknowingly, we live our lives enduring the fact that what we long for must always, in the end, elude our grasp. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu /+/ ]

“Thus, for Buddha, all life is suffering..and the story gets worse! The Buddha adopted from his Hindu religious environment the doctrine of samsara, the belief that all existence is an endless cycle of life, death, and rebirth. Therefore, when the Buddha tells us that we must endure nothing but suffering all our lives, he is not speaking of decades of unhappiness; suffering is forever. In the Buddhist picture, life is not much different from hell, except the flames are missing, so it's easy to mistake where you are. /+/

“The Buddha preached this picture of life in a formula known as the Four Noble Truths, the most basic doctrine of Buddhism. These truths tell us, 1) that life in samsara is suffering; 2) that this has a cause..our longing for illusory things; 3) that this suffering may be ended by following the path of the Buddha; 4) what that path is. The first two truths comprise the basic worldview of Buddhist thought. The final two truths point towards the practical core of Buddhism: its path towards salvation through self-cultivation in the manner of the Buddha's own struggle to enlightenment.” /+/

Why are Suffering, Self-Denial and Nothingness Such Big Deals in Buddhism?

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “Most of us who first hear the Four Noble Truths have an initially negative response. Not only do the first two paint an unrelievedly depressing picture of life, but they do not seem to most of us true. After all, life has many obvious pleasures: food, love, music, cable. Why focus solely on the bad side? Furthermore, it is not at all clear that the Buddha was strictly correct about the illusory nature of things. For example, many people have strong convictions about the real existence of tables and chairs. It is not certain how the historical Buddha responded to audiences who may have raised these objections. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu /+/ ]

Four sights of Gautama Siddhartha after left his palace with his horse Kanthaka and charioteer Channa: 1) old age; 2) death; 3) sickness; 4) and asceticism

“However, one of the principal activities of those who did choose to heed the Buddha's message and follow his teachings was the elaboration of a rich and sophisticated set of philosophical arguments that were designed to demonstrate the coherence of the Buddha's claims about the nature of the world. These arguments form the basis of Buddhist philosophy, which includes distinctive doctrines of metaphysics (theory of the basic structures of reality), psychology, ethics, and logic. Although some of Buddha's early audiences surely doubted his words, others were inclined to adopt his portrait of life as suffering. The poor and the sick would more easily see a message such as Buddha's as one of hope rather than despair, and Hindu yogins who had withdrawn from society would have seen in the Buddha's picture of an illusory world confirmation of their own decisions. For such people, the last two Noble Truths represented a path to salvation, albeit a very difficult path, involving years of self-denial and rigorous meditational training. /+/

“But the Buddha's own picture of salvation seems to have been so bare that few others would have found it enticing. For the Buddha, the ultimate goal of any conscious being was simply release from samsara and the cessation of suffering..and that was it! No afterlife, no paradise, no talk with Elvis. Nothing. In fact, “nothing” was the only description offered of the state of permanent release from samsara: the state of nirvana. Nirvana was simply no longer being. For those who do not share the Buddhist belief in reincarnation, nirvana looks very much like death. /+/

“While all of us have bad days, few would respond by undertaking years of rigorous self-denial leading to personal extinction. Therefore, those who followed the Buddha realized early on that to enlarge the audience of their faith it would be necessary to make the path easier for most to travel and the end goal more attractive. These Buddhist disciples gradually built up a very large corpus of sacred texts and devotional practices that added to Buddhism inspirational religious features. self-cultivation came to involve more than meditation.-one could approach nirvana now through doing good works, chanting holy scripture, praying to scores of Buddhist saints, and contributing tax-free gifts to Buddhist monasteries. And nirvana too was gradually redesigned into a sort of super-physical space in which the souls of perfected people enjoyed the company of the gods and saints for eternity, in surroundings as comfortable and gemlike as the palace from which Siddhartha Gautama had once fled....These ideas were not without problems. Buddhist philosophy is very firm in rejecting the existence of the soul or any enduring principle of personal identity in life or in nirvana. But the philosophical and religious aspects of Buddhism, like two spouses, learned to live together without worrying overmuch about perfect consistency. /+/

“Through the development of a philosophical core that could defend the very counter-intuitive claims that the Buddha made about reality, and the development of a religious tradition that greatly enhanced the attractiveness of Buddhism's salvational message, Buddhism supplied itself with tools that enabled it to emerge from India and sweep over all of East Asia, becoming a dominant religious tradition there for over a thousand years.” /+/

Buddhist Sects

There are three main Buddhist schools (sects): 1) Theravada Buddhism, 2) Mahayana Buddhism, and 3) Vajrayana (Tibetan Buddhism). These schools promote different concepts, practices and value systems. Arguably the single most unifying factor for all the world's Buddhists is the Buddha Siddhartha Gautama, himself, Although the different Buddhist schools have different understandings and attitudes toward the Buddha, each of them, without exception, respects and reveres him. What makes the Buddha so significant in Buddhism is not only is he the founder and voice of Buddhism, his lifestyle serves as an example for all Buddhists. It is not embrace The Buddha’s teachings or to worship him, one must also strive to be like the Buddha and live like him.

According to the Asia Society Museum: “Three main types of Buddhism have developed over its long history, each with its own characteristics and spiritual ideals." Theravada Buddhism, "often known by the pejorative term Hinayana ("Lesser Vehicle"), is the earliest of the three and emphasizes the attainment of salvation for oneself alone and the necessity of monastic life in order to attain spiritual release. The Mahayana ("Greater Vehicle"), whose members coined the word "Hinayana" and believed its adherents pursued a path that could not be followed by the majority of ordinary people, teaches the salvation of all. Practitioners of the Vajrayana ("Diamond Vehicle"), or Esoteric Buddhism, believe that one can achieve enlightenment in a single lifetime, as opposed to the other two types, which postulate that it takes many eons to accrue the necessary good karma. [Source: Asia Society Museum asiasocietymuseum.org ]

These three types were not mutually exclusive, but their emphasis on different practices affected Buddhist art. For example, whereas foundational Buddhism teaches that only a few devotees are able to reach enlightenment and that they do so through their own efforts, Mahayana and its later offshoot, Vajrayana, teach that buddhahood is attainable by everyone with help from beings known as bodhisattvas. As a result, images of bodhisattvas proliferated in Mahayana and Vajrayana art and are often depicted flanking buddhas.

See Articles Under THERAVADA BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com ; MAHAYANA BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com TIBETAN BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com

geographical location of the main Buddhist divisions

The Buddha Foretells the Gradual Decline of Religion

The 'Anagatavamsa' reads: “Praise to that Lord, Arahant, perfect Buddha. Thus have I heard: At one time the Lord was staying near Kapilvatthu in the Banyan monastery on the bank of the river Rohani Then the venerable Sariputta questioned the Lord about the future Conqueror: 'The Hero that shall follow you, The Buddha-of what sort will he be? I want to hear of him in full. Let the Visioned One describe him.' When he had heard the Elder's speech The Lord spoke thus: 'I will tell you, Sariputta, Listen to my speech. [Source: Translation by Edward Conze, in Conze et al., “Buddhist Texts through the Ages” (Oxford: Bruno Cassirer (Publishers) Ltd., 1954), Eliade Page website]

Three leaders have there been: Kakusandha, Konagamana And the leader Kassapa too. 'I am now the perfect Buddha, And there will be Metteyya [i.e., Maitreya] too Before this same auspicious aeon Runs to the end of its years. 'The perfect Buddha, Metteyya By name, supreme of men.' (Then follows a history of the previous existence of Metteyya . . . and then the description of the gradual decline of the religion:)

'How will it occur? After my decease there will first be five disappearances. What five? The disappearance of attainment (in the Dispensation), the disappearance of proper conduct, the disappearance of learning, the disappearance of the outward form, the disappearance of the relics. There will be these five disappearances. 'Here attainment means that for a thousand years only after the lord's complete Nirvana will monks be able to practice analytical insights. As time goes on and on these disciples of mine are nonreturners and once-returners and stream-winners. There will be no disappearance of attainment for these. But with the extinction of the last stream-winner's life, attainment will have disappeared. 'This, Sariputta, is the disappearance of attainment.

'The disappearance of proper conduct means that, being unable to Practice jhana, insight, the Ways and the fruits, they will guard no lore the four entire purities of moral habit. As time goes on and on they will only guard the four offences entailing defeat. While there are even a hundred or a thousand monks who guard and bear in mind the four offences entailing defeat, there will be no disappearance of proper conduct. With the breaking of moral habit by the last monk- or on the extinction of his life, proper conduct will have disappeared. 'This, Sariputta, is the disappearance of proper conduct.

'The disappearance -of learning means that as long as there stand firm the texts with the commentaries pertaining to the word of the Buddha in the three Pitakas, for so long there will be no disappearance of learning. As time goes on and on there will be base-born kings, not Dhamma-men; (dharma) their ministers and so on will not be Dhamma-men, and consequently the inhabitants of the kingdom and so on will not be Dhamma-men. Because they are not Dhamma-men it will not rain properly. Therefore the crops will not flourish well, and in consequence the donors of requisites to the community of monks will not be able to give them the requisites. Not receiving the requisites the monks will not receive pupils. As time goes on and on learning will decay. In this decay the Great Patthana itself will decay first. In this decay also (there will be) Yamaka, Kathavatthu, Puggalapannati, Dhatukatha, Vibhanga and Dhammasangani. When the Abhidhamma Pitaka decays the Suttanta Pitaka will decay. When the Suttantas decay the Anguttara will decay first. When it decays the Samyutta Nikaya, the Majjhima Nikaya, the Digha Nikaya and the Khuddaka-Nikaya will decay. They will simply remember the jataka together with the Vinaya Pitaka. But only the conscientious (monks) will remember the Vinaya Pitaka. As time goes on and on, being unable to remember even the jataka, the Vessantara-jataka will decay first. When that decays the Apannaka-jataka will decay. When the jatakas decay they will remember only the Vinaya-Pitaka. As time goes on and on the Vinaya-Pitaka will decay. While a four-line stanza still continues to exist among men, there will not be a disappearance of learning. When a king who has faith has had a purse containing a thousand (coins) placed in a golden' casket on an elephant's back, and has had the drum (of proclamation) sounded in the city up to the second or third time, to the effect that: "Whoever knows a stanza uttered by the Buddhas, let him take these thousand coins together with the royal elephant"-but yet finding no one knowing a four-line stanza, the purse containing the thousand (coins) must be taken back into the palace again-then will be the disappearance of learning. 'This, Sariputta, is the disappearance of learning.

Tibetan Wheel of Life

'As time goes on and on each of the last monks, carrying his robe, bowl, and tooth-pick like Jain recluses, having taken a bottle-gourd and turned it into a bowl for almsfood, will wander about with it in his forearms or hands or hanging from a piece of string. As time goes on and on, thinking: 'What's the good of this yellow robe?" and cutting off a small piece of one and sticking it on his nose or ear or ill his hair, he will wander about supporting wife and children by agriculture, trade and the like. Then he will give a gift to the Southern community for those (of bad moral habit). I say that he will then acquire an incalculable fruit of the gift. As time goes on and on, thinking: "What's the good of this to us?", having thrown away the piece Of yellow robe, he will harry beasts and birds in the forest. At this time the outward form will have disappeared. 'This, Sariputta, is called the disappearance of the outward form.

'Then when the Dispensation of the Perfect Buddha is 5,000 years old, the relics, not receiving reverence and honour, will go to places where they can receive them. As time goes on and on there will not be reverence and honour for them in every place. At the time when the Dispensation is falling into (oblivion), all the relics, coming from every place: from the abode of serpents and the deva-world and the Brahma-world, having gathered together in the space round the great Bo-tree, having made a Buddha-image, and having performed a "miracle" like the Twin-miracle, will teach Dhamma. No human being will be found at that place. All the devas of the ten-thousand world system, gathered together, will hear Dhamma and many thousands of them will attain to Dhamma. And these will cry aloud, saying: "Behold, devatas, a week from today our One of the Ten Powers will attain complete Nirvana." They will weep, saying: "Henceforth there will be darkness for us." Then the relics, producing the condition of heat, will burn up that image leaving no remainder. 'This, Sariputta, is called the disappearance of the relics.'

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons except Four Noble Truths, Rissho Kosei-kai, and Hindu symbols, culturalsymbolism.wordpress.com; the four sights, gauthamabuddha.blogspot.com

Text Sources: East Asia History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu , “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org, Asia for Educators, Columbia University; Asia Society Museum “The Essence of Buddhism” Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius, 1922, Project Gutenberg, Virtual Library Sri Lanka “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World's Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures: Volume 5 East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1993); BBC, Wikipedia, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, and various books and other publications.

Last updated January 2024