BUDDHIST MORALITY

Chiang Mai, Thailand

Buddhism provides guidelines for village justice, namely in the form of the five basic moral prohibitions (the Panch Sila, or the five precepts for the laity): 1) refrain for taking life; 2) don't steal; 3) avoid illicit sexual activity; 4) don't speak falsely; and 5) refrain from consuming inebriating substances. These guidelines are supposed to be followed by both lay people and monks. Devout Buddhists and monks are also supposed observe a number of other prohibitions such as avoiding dancing, singing, eating after midday and wearing jewelry and cosmetics.

The religious historian I.B. Hunter wrote: “The criteria of Buddhist morality is to ask yourself , when there is one of three kinds of deeds you want to do, whether it will lead to the hurt of self, of others, or of both. If you come to the conclusion that it will be harmful, then you must not do it. But if you form the opinion that it will be harmless, then you can do it and repeat. A person that torments neither himself or another is already transcending the active life."

Among Mahayana Buddhists there is a great deal of discussion of what is beneficial for people and what isn't since people don't always necessarily know what is good for them. Mahayana scholars discuss things like whether it is an act of kindness to kill an animal in extreme pain or give whiskey to an alcoholic and debate about the merits of medical technology which can make people healthier but ultimately is a benefit provided by material objects rather than spirituality.

Buddhism's success as a religion has been at least partly attributed to the universality of its ethical teaching and the flexibility of its spiritual message. It provides a code of conduct for the community and the individual that provides a framework for a peaceful society and peace of mind. Buddhism is arguably the most tolerant and adaptable religion. Wherever it has gone it has adapted to local conditions. That is one reason why there are so many different sects and schools and it is winning so many adherents today in the West. Buddha preached against the caste system. Much of Buddhist morality is based in on the basic Buddhist premise that life is full of suffering.

Jacob Kinnard wrote in the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: In general, because Buddhism has no single, centralized religious authority, and because it philosophically and practically places the emphasis on individual effort, there is no single stance on any controversial issue. Buddhists, if it is possible to generalize, tend to believe that most issues are decided by the individual or by the basic ethical guidelines that were first laid out by the Buddha himself and then subsequently elaborated on in the Vinaya Pitaka. One central tenet that informs Buddhist's understanding of such controversial issues as capital punishment and abortion is the prohibition against harming any living beings. Issues such as divorce, which can frequently be governed by religious rules and authorities, are generally left up to the individuals involved.

Websites and Resources on Buddhism: Buddha Net buddhanet.net/e-learning/basic-guide ; Internet Sacred Texts Archive sacred-texts.com/bud/index ; Introduction to Buddhism webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/buddhaintro ; Early Buddhist texts, translations, and parallels, SuttaCentral suttacentral.net ; East Asian Buddhist Studies: A Reference Guide, UCLA web.archive.org ; View on Buddhism viewonbuddhism.org ; Tricycle: The Buddhist Review tricycle.org ; BBC - Religion: Buddhism bbc.co.uk/religion

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“Buddhist Ethics: A Philosophical Exploration” by Jay L. Garfield Amazon.com ;

“The Four Noble Truths” by His Holiness the Dalai Lama Amazon.com ;

“The Middle Way: Faith Grounded in Reason”

by His Holiness the Dalai Lama and Thupten Jinpa Ph.D. Ph.D. Amazon.com ;

“The Noble Eightfold Path: Way to the End of Suffering” by Bhikkhu Bodhi Amazon.com ;

“Samsara, Nirvana, and Buddha Nature” by His Holiness the Dalai Lama and Thubten Chodron Amazon.com ;

“Buddhist Scriptures” by Donald Lopez (Penguin Classics) Amazon.com ;

“What the Buddha Taught” by Walpola Rahula Amazon.com ;

“In the Buddha's Words: Anthology of Discourses from the Pali Canon” with Bhikkhu Bodhi, the Dalai Lama Amazon.com ;

“The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching” by Thich Nhat Hanh Amazon.com ;

“Mindfulness in Plain English Paperback” by Bhante Bhante Gunaratana (Author) Amazon.com

Buddhist Teachings About Morality

The Sri Lankan monk Aryadasa Ratnasinghe wrote: “Buddhism is, generally, accepted as a moral philosophy to lead mankind in the proper path by doing good and avoiding evil. The Buddha himself has expressed that his teaching is both deep and recondite, and anyone could follow it who is intelligent enough to understand it. He admonished his disciples to be a refuge to themselves' and never to seek refuge in, or help from anyone else. He taught, encouraged and stimulated each person to develop himself, and to work out his own emancipation, because man has the power to liberate him self from all earthly bondage, through his own personal effort and intelligence.^^^

“Buddha based his doctrine on the Four Noble Truths, viz: suffering ('dukkha'), cause of suffering ('samudaya'), destruction of suffering ('nirodha') and the path leading to the cessation of suffering ('magga'). The first is to be comprehended, the second (craving) is to be eradicated, the third (Nibbana) is to be realised, and the fourth (the Noble Eightfold Path) is to be developed. This is the philosophy of the Buddha for the deliverance of mankind from being born again, or the cessation of continuity of becoming, i.e., 'Bhavanirodha' (the attainment of Nibbana). ^^^

“The Noble Eightfold Path, also known as the Middle Way, consists eight factors, namely right understanding, right thought, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right mindfulness and right concentration. Practically, the whole teaching of the Buddha, to which he devoted himself during his 45 years of ministration, deals in some way or another, with this Path. He explained it in different ways and in different words, to different people, at different times, according to mental development and capacity of a person, to understand and follow the teachings of the Buddha. In classical terminology, it is known as 'Dukkhanirodhagaminipatipada ariyasacca'. ^^^

This Middle Way is neither a metaphysical path nor a ritualistic path, neither dogmatism nor scepticism, neither self-indulgence nor self-mortification, neither externalism nor nihilism, neither pessimism nor optimism, but the path for Enlightenment as the means of deliverance from suffering, and man is solely responsible for his own pains or pleasures. Buddhism is clear, reasonable and gives complete answerers to all important aspects and questions about our lives.

These eight factors aim in promoting and perfecting the three essentials of Buddhist discipline, viz. Ethical conduct ('sila'), concentration ('samadhi') and wisdom (panna'). Ethical conduct is built on the conception of morality with compassion towards all beings. Concentration means securing a firm footing on the ground of morality where the aspirant embarks upon the higher practice on the control and culture of the mind. Beyond morality is wisdom. The base of Buddhism is morality and wisdom is its apex. It is the right understanding of the nature of the world in the light of transiency ('anicca'), sorrowfulenss ('dukkha') and soullessness ('anatta').

Wisdom leads to the state of 'dhyana' (psychic faculty), generally called trance. Wisdom covers a very wild field, comprising understanding, knowledge, and insight specific to Buddhism. Wisdom being the apex of Buddhism, is the first factor of the Noble Eightfold Path.

It is one of the seven factors of Enlightenment, some of the four means of accomplishment, one of the five powers ('pannabala') and one of the five controlling faculties ('panna indriya).

The highest morality is inculcated in the system of Buddhist thought, since it permits freedom of thought and opinion, sets its norms against persecution and cruelty and recognises the right of animals. Liquor, drugs and opium and all that tends to destroy the composure of the mind are discountenanced. When considering the fraternity of people, Buddhism acknowledges no caste system and admits the perfect equality of all men, as it proclaims the universal brotherhood.

See Separate Articles: FOUR NOBLE TRUTHS OF BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com ; MIDDLE WAY AND THE EIGHTFOLD PATH factsanddetails.com

Buddhist Sources on Morality

Tibetan wrathful diety Instruct yourself (more and more) in the highest morality.—Nagarjuna's "Friendly Epistle." [Source: “The Essence of Buddhism” Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius, 1922, Project Gutenberg]

Wealth and beauty, scented flowers and ornaments like these, are not to be compared for grace with moral rectitude!—Fo-sho-hing-tsan-king.

No fear has any one of me; neither have I fear of any one: in my good-will to all I trust.—Introduction to the Jataka.

Our deeds, whether good or evil, ... follow us as shadows.—Fo-sho-hing-tsan-king.

As he said so he acted.—Vangisa-sutta.

Neither is it right to judge men's character by outward appearances.—Ta-chwang-yan-king-lun.

Like a ... flower that is rich in color, but has no scent, so are the fine ... words of him who does not act accordingly.—Dhammapada.

Morality brings happiness: ... at night one's rest is peaceful, and on waking one is still happy.—Udanavarga.

Hear ye all this moral maxim, and having heard it keep it well: Whatsoever is displeasing to yourselves never do to another.—Bstanhgyur.

Then declared he unto them (the rule of doing to others what we ourselves like).—San-kiao-yuen-lieu.

Buddhism and Character

The religious scholar A.C. Graham wrote: “Buddhism is a “Nay-saying” religion, rejecting all life as suffering and promising release from it; yet when one is actually in a Buddhist country it is hard to resist the impression that one is among the liveliest, the most invincibly cheerful, the most “yea-saying” people on earth."

Describing his people the King of Thailand told National Geographic magazine, "Thais seem to be happy go lucky but are quite strong. Our people are relaxed, not high strung or stiff. They are hospitable to strangers and to new ideas. The majority are Buddhist — and the Buddhists have never had a holy war. They are polite. Honorable politeness. They have courage but are not harsh’strong but gentle."

Poor people in Buddhist countries often have a big smiles on their faces, something that many people believe is attributed to the fact they spend so much time praying and engaging religious activities. Religion is a daily, if not hourly, practice for many Buddhists. Tibetans, for example, seem to spend hours each day praying or spinning prayer wheels.

Buddhism encourages its practitioners to keep their emotions and passions in check and stresses karma over determination, which often means people are more willing to accept their lot in life and look for happiness in future lives. This outlook and is sometimes viewed in the West as a lack of ambition or unwilling to work hard to get ahead.

The teaching of right speech in the Noble Eightfold Path, condemn all speech that is in any way harmful (malicious and harsh speech) and divisive, encouraging to speak in thoughtful and helpful ways. The Pali Canon explains: And what is right speech? Abstaining from lying, from divisive speech, from abusive speech, and from idle chatter: This is called right speech.

Patience is a great virtue especially to Mahayana Buddhists. One passage from the Manual of Zen Buddhism goes: “However unnumerable sentient beings are, I vow to save them! However inexhaustible the defilements are, I vow to extinguish them! However immeasurable the dharmas are, I vow to master them! However incomparable Enlightenment is, I vow to attain it! Mahayana Buddhists see patience in terms of moral patience to endure suffering and hostile acts of others and intellectual patience to accept ideas — especially ones that seem so unfathomable and unpleasant like the non-existence of all things — before understanding them.

Buddhist Sources on Good Character

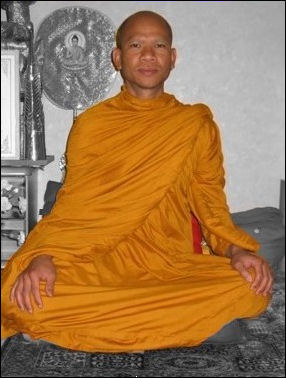

Examination for Thai monks Reverently practicing the four gracious acts— Benevolence, charity, humanity, love; Doing all for the good of men, and that they in turn may benefit others. —Phu-yau-king. [Source: “The Essence of Buddhism” Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius, 1922, Project Gutenberg]

All men should cultivate a fixed and firm determination, and vow that what they once undertake they will never give up.—Fo-pen-hing-tsih-king.

Rather will I fall headlong into hell ... than do a deed that is unworthy.—Jataka.

May my body be ground to powder small as the mustard-seed if I ever desire to (break my vow)!—Fo-pen-hing-tsih-king.

Upright, conscientious and of soft speech, gentle and not proud.—Metta-sutta.

Uprightness is his delight.—Tevijja-sutta.

He injures none by his conversation.—Samanna-phala-sutta.

Not the whole world, ... the ocean-girt earth, With all the seas and the hills that girdle it, Would I wish to possess with shame added thereto. —Questions of King Milinda.

(To the) self-reliant there is strength and joy.—Fo-sho-hing-tsan-king.

Have a strict control over your passions.—Story of Sundari and Nanda. [Source: “The Essence of Buddhism” Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius, 1922, Project Gutenberg]

Practice the art of "giving up."—Fo-sho-hing-tsan-king.

Control your tongue.—Dhammapada.

Offensive language is harsh even to the brutes.—Suttavaddhananiti.

Aiming to curb the tongue, ... aiming to benefit the world.—Fo-sho-hing-tsan-king.

He knew not the art of hypocrisy.—Jatakamala.

Ask not of (a person's) descent, but ask about his conduct—Sundarikabharadvaja-sutta.

Keep watch over your hearts.—Mahaparinibbana-sutta.

Above all things be not careless; for carelessness is the great foe to virtue. —Fo-sho-hing-tsan-king.

The member of Buddha's order should abstain from theft, even of a blade of grass.—Mahavagga.

Earnestly practice every good work.—Fo-sho-hing-tsan-king.

From bribery, cheating, fraud, and (all other) crooked ways he abstains.—Tevijja-sutta. The Scripture moveth us, therefore, rather to cut off the hand than to take anything which is not ours.—Sha-mi-lu-i-yao-lio.

Let him not, even though irritated, speak harsh words.—Sariputta-sutta.

What he hears he repeats not there, to raise a quarrel against the people here.—Tevijja-sutta.

From this day forth, ... although much be said against me, I will not feel spiteful, angry, enraged, or morose, nor manifest anger and hatred.—Anguttara-Nikaya.

Five Precepts: The Buddhist Guide to Good Behavior

Chinese monks

The Five Precepts by which all Buddhists are expected to refrain from are: 1) harming living things; 2) taking what is not given; 3) sexual misconduct; 4) lying or gossip; 5) taking intoxicating substances such as drugs or drink. These five moral precepts are not commandments but aspirations voluntarily undertaken by individuals.

Jacob Kinnard wrote in the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: The pancha sila are the basic ethical guidelines for the layperson, although they are not necessarily followed rigidly by everyone. In some ways they are rather like the Ten Commandments in Judaism and Christianity, in that they are the basis for ethical behavior, a kind of practical blueprint. A fundamental difference from the Ten Commandments, though, is that the pancha sila are voluntarily followed and are a matter of personal choice, not an imperative to act in a particular manner.

1) The first guideline is No killing. The basic idea here is that every individual is connected with all other living beings. Buddhists go to considerable lengths to qualify this precept, giving five conditions that govern it: (1) presence of a living being, (2) knowledge of this, (3) intention to kill, (4) act of killing, and (5) death. What is most important about this first precept is not its negative form, injunction against killing, but its positive aspect, that of compassion and loving kindness. This positive aspect is one of the most common things upon which laypeople meditate, often with this verse from the Metta Sutta: "May all beings be happy and secure; / May their hearts be wholesome. / Whatever living beings there be — / Feeble or strong, tall, stout or medium, / Short, small or large, without exception — / Seen or unseen, / Those dwelling far or near, / Those who are born or who are to be born, / May all beings be happy."

2) The second guideline is No taking what is not given. This is particularly important for the monks. Here the concept of dana is crucial. Because one of the chief ethical activities of the layperson is to give unselfishly to the sangha, this giving is contingent on the monks accepting, also unselfishly, whatever is given. The monks are not to take anything that is not given to them. This holds true also for the layperson, in that he or she is not to steal.

3) The third guideline is No sexual misconduct. This prevents lust and envy, which are the most powerful forms of thirst (tanha). 4) The fourth guideline is No false speech. Lies create deception and illusion and lead to grasping. Also, for the monks, this is about not speaking false doctrines. 5) The fifth guideline is No liquor, which clouds the mind and prevents sati (mindfulness).

In addition to these five basic principles, monks follow additional basic rules, sometimes three, sometimes five: No untimely meals (thereby promoting group sharing of food and hindering the desire to hoard); No dancing or playing of music (thereby promoting a sober, nonfrivolous life); No adornments or jewelry (which would be against the basic ascetic attitude of the monk); No high seats (an injunction intended to promote equality in the sangha); and No handling of money (thereby preventing greed and attachments).

Buddha's Words on Kindness (Metta Sutta)

Sakyamuni Buddha from Bodhgaya

The Buddha said: This is what should be done

By one who is skilled in goodness,

And who knows the path of peace:

Let them be able and upright,

Straightforward and gentle in speech.

Humble and not conceited,

Contented and easily satisfied.

Unburdened with duties and frugal in their ways.

Peaceful and calm, and wise and skillful,

Not proud and demanding in nature.

Let them not do the slightest thing

That the wise would later reprove.

Wishing: In gladness and in saftey,

May all beings be at ease.

Whatever living beings there may be;

Whether they are weak or strong, omitting none,

The great or the mighty, medium, short or small,

The seen and the unseen,

Those living near and far away,

Those born and to-be-born,

May all beings be at ease!

Let none deceive another,

Or despise any being in any state.

Let none through anger or ill-will

Wish harm upon another.

Even as a mother protects with her life

Her child, her only child,

So with a boundless heart

Should one cherish all living beings:

Radiating kindness over the entire world

Spreading upwards to the skies,

And downwards to the depths;

Outwards and unbounded,

Freed from hatred and ill-will.

Whether standing or walking, seated or lying down

Free from drowsiness,

One should sustain this recollection.

This is said to be the sublime abiding.

By not holding to fixed views, [Source: Dharma.net]

The pure-hearted one, having clarity of vision,

Being freed from all sense desires,

Is not born again into this world.

Buddhist Sources on Goodness

girls dressed up like Apsaras in Laos

This good man, moved by pity, gives up his life for another, as though it were but a straw.—Nagananda. [Source: “The Essence of Buddhism” Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius, 1922, Project Gutenberg]

He lived for the good of mankind.—Jatakamala.

Full of truth and compassion and mercy and long-suffering.—Jataka.

What is goodness? First and foremost the agreement of the will with the conscience.—Sutra of Forty-two Sections.

'Tis thus men generally think and speak, they have a reference in all they do to their own advantage. But with this one it is not so: 'tis the good of others and not his own that he seeks.—Fo-pen-hing-tsih-king.

From henceforth ... put away evil and do good.—Jataka.

At morning, noon, and night successively, store up good works.—Fo-sho-hing-tsan-king.

Always doing good to those around you.—Fo-pen-hing-tsih-king.

In order to terminate all suffering, be earnest in performing good deeds.—Buddhaghosa's parables.

He who does wrong, O king, comes to feel remorse.... But he who does well feels no remorse, and feeling no remorse, gladness will spring up within him.—Questions of King Milinda.

Buddhist Sources on Duty and Reaping What You Sow

Walk in the path of duty, do good to your brethren, and work no evil towards them.—Avadana Sataka. [Source: “The Essence of Buddhism” Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius, 1922, Project Gutenberg]

Intent upon benefiting your fellow-creatures.—Katha Sarit Sagara.

Let none be forgetful of his own duty for the sake of another's.—Dhammapada.

Better to fling away life than transgress our convictions of duty.—Ta-chwang-yan-king-lun.

He who, doing what he ought, ... gives pleasure to others, shall find joy in the other world.—Udanavarga.

Losar in Tibet

Religion means self-sacrifice.—Rukemavati.

I consider the welfare of all people as something for which I must work.—Rock Inscriptions of Asoka.

Our duty to do something, not only for our own benefit, but for the good of those who shall come after us.—Fo-pen-hing-tsih-king.

As men sow, thus shall they reap.—Ta-chwang-yan-king-lun.

Actions have their reward, and our deeds have their result.—Mahavagga.

Our deeds are not lost, they will surely come (back again).—Kokaliya-sutta.

Reaping the fruit of right or evil doing, and sharing happiness or misery in consequence.—Fo-sho-hing-tsan-king.

Doing good we reap good, just as a man who sows that which is sweet (enjoys the same).—Fa-kheu-pi-us.

Buddhist Sources on Social Relations

Liberty, courtesy, benevolence, unselfishness, under all circumstances towards all people—these qualities are to the world what the linchpin is to the rolling chariot. —Sigalovada-sutta. [Source: “The Essence of Buddhism” Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius, 1922, Project Gutenberg]

Since even animals can live together in mutual reverence, confidence, and courtesy, much more should you, O Brethren, so let your light shine forth that you ... may be seen to dwell in like manner together.—Cullavagga.

Trust is the best of relationships.—Dhammapada.

Faithful and trustworthy, he injures not his fellow-man by deceit.—Tevijja-sutta.

He sought after the good of those dependent on him.—Questions of King Milinda.

Who, though he be lord over others, is patient with those that are weak.—Udanavarga.

Loving her maids and dependents even as herself.—Lalita Vistara.

Loving all things which live even as themselves.—Sir Edwin Arnold.

Judge not thy neighbor.—Siamese Buddhist Maxim.

Buddhist Sources on Friendship

Korean monks

Look with friendship ... on the evil and on the good.—Introduction to Jataka Book. [Source: “The Essence of Buddhism” Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius, 1922, Project Gutenberg]

If thou see others lamenting, join in their lamentations: if thou hear others rejoicing, join in their joy.—Jitsu-go-kiyo.

Let us be knit together ... as friends.—Fo-sho-hing-tsan-king.

(The true friend) forsakes you not in trouble; he will lay down his life for your sake.—Sigalovada-sutta.

In grief as well as in joy we are united, In sorrow and in happiness alike. That which your heart rejoices in as good, That I also rejoice in and follow. It were better I should die with you, Than ... attempt to live where you are not. —Fo-pen-hing-tsih-king.

His friendship is prized by the gentle and the good.—Fo-sho-hing-tsan-king.

All the people were bound close in family love and friendship.—Fo-sho-hing-tsan-king.

A heart bound by affection does not mind imminent peril. Worse than death to such a one is the sorrow which the distress of a friend inflicts.—Jatakamala.

Buddhist Sources on Ways to Treat Others

Hurt not others with that which pains yourself.—Udanavarga. [Source: “The Essence of Buddhism” Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius, 1922, Project Gutenberg]

The man of honor should minister to his friends ... by liberality, courtesy, benevolence, and by doing to them as he would be done by.—Sigalovada-sutta.

Speak not harshly to anybody.—Dhammapada.

May I speak kindly and softly to every one I chance to meet.—Inscription in Temple of Nakhon Vat.

Courtesy is the best ornament. Beauty without courtesy is like a grove without flowers.—Buddha-charita.

Let not one who is asked for his pardon withhold it.—Mahavagga.

Always intent on bringing about the good and the happiness of others.—Jatakamala.

If they may cause by it the happiness of others, even pain is highly esteemed by the righteous, as if it were gain.—Jatakamala.

Let him not think detractingly of others.—Sariputta-sutta.

But offer loving thoughts and acts to all.—Sir Edwin Arnold.

Never should he speak a disparaging word of anybody.—Saddharma-pundarika.

Lightly to laugh at and ridicule another is wrong.—Fa-kheu-pi-us.

Buddhist Views on the Treatment of Animals

According to the BBC: “Although Buddhism is an animal-friendly religion, some aspects of the tradition are surprisingly negative about animals. Buddhism requires us to treat animals kindly: 1) Buddhists try to do no harm (or as little harm as possible) to animals; 2) Buddhists try to show loving-kindness to all beings, including animals; 3) The doctrine of right livelihood teaches Buddhists to avoid any work connected with the killing of animals. The doctrine of karma teaches that any wrong behaviour will have to be paid for in a future life - so cruel acts to animals should be avoided. Buddhists treat the lives of human and non-human animals with equal respect. [Source: BBC |::|]

“Buddhists see human and non-human animals as closely related: 1) both have Buddha-nature

both have the possibility of becoming perfectly enlightened; 2) a soul may be reborn either in a human body or in the body of a non-human animal. Buddhists believe that is wrong to hurt or kill animals, because all beings are afraid of injury and death:”

All living things fear being beaten with clubs.

All living things fear being put to death.

Putting oneself in the place of the other,

Let no one kill nor cause another to kill. — Dhammapada 129

See Separate Article: BUDDHISM, ANIMALS, LIVING THINGS AND HUMAN LIFE factsanddetails.com

Moral and Ethical Challenges in Buddhism

Jacob Kinnard wrote in the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices: One of the things that makes the theory and practice of ethics (sila) particularly interesting in the Buddhist context is the tension that exists, right on the surface, between the individual's responsibility for his or her own salvation — as exemplified by the Buddha's advice that one must be one's own island (atta dipa), dependent on no one other than one's self for salvation — and the individual's connection with social life, as governed by the collective nature of karma. This is perhaps most dramatically illustrated by the Buddha's own life story. For instance, in Johnston's translation of The Buddhacarita, or, Acts of the Buddha, the young Siddhartha's wife, Yashodhara, when she hears that Siddhartha has abandoned her, falls upon the ground "like a Brahminy duck without its mate" — a common symbol of lifelong marital partnership, such that one duck will die of remorse upon the death of the other. Likewise, his son is described as "poor Rahula," who is fated "never to be dandled in his father's lap" (pp. viii, 58).[Source: Jacob Kinnard, Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices, 2018, Encyclopedia.com]

The ethical and moral challenge is always to strike a balance between one's concern for the suffering of others and one's own progress on the path; too much concern for other people can be a hindrance, just as not enough can generate negative karma. The key to Buddhist ethics, if not in fact to the whole of the Buddha's teachings, is the cultivation of mindfulness (sati) — to develop a mental attitude of complete and selfless awareness, a mental attitude that necessarily influences the manner in which one acts toward other living beings, a mental awareness that fundamentally informs one's every act and intention to act.

For the monk the ethical system is extremely complex and extensive, contained primarily and explicitly in the Vinaya but secondarily and implicitly in every utterance of the Buddha. To be a monk is to be necessarily ethical. For the layperson the ethical guidelines are less specific, seeming to amount to "live the proper life." This means that one must be aware that all acts and all beings are part of samsara and are thus caught up in karma and pratitya-samutpada (Pali, paticca-samuppada; the chain of conditioned arising). Whatever one does has effects, and those effects are not always obvious. The implications here are perhaps best ethically stated when the Buddha says, "Oh Bhikkhus, it is not easy to find a being who has not formerly been your mother, or your father, your brother, your sister or your son or daughter" (Samyutta Nikaya, vol. II, p. 189). In other words, any act necessarily affects not only the immediate actor but all beings, who are, logically, karmically connected.

It is also important to remember that we are still within the basic Brahmanical milieu here. What we see in Buddhism, however, is an emphasis on the individual as he or she fits into society, not an emphasis on how society molds or controls the individual, as we see in Hinduism, where the emphasis is on order and duty, on making sure that everything and everyone stays in the proper place — hence caste, life stages, and so on. This is not to say that this societal component is entirely absent in Buddhism, since one of the motivations for the individual to act ethically is to make society work. Without social order things would fall utterly apart, as is perhaps best articulated in what is sometimes called the Buddhist book of Genesis, the Aganna Sutta, which describes a social world in which chaos and decay emerge precisely because beings act greedily and selfishly. Proper, ethical action in Buddhism is not performed out of duty or some higher cosmic order, however; rather, one acts ethically out of one's own free will, because without such proper action, the individual can make no progress on the path.

Text Sources: East Asia History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu , “Topics in Japanese Cultural History” by Gregory Smits, Penn State University figal-sensei.org, Asia for Educators, Columbia University; Asia Society Museum “The Essence of Buddhism” Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius, 1922, Project Gutenberg, Virtual Library Sri Lanka; “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World's Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures: Volume 5 East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1993); BBC, Wikipedia, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024