SYMBOLS AND FEATURES ON BUDDHA MAGES

There are many symbolic gestures and objects found on images of The Buddha that have important meanings. A raised hand means no fear. Curly hair, elongated ears and hands with eyes are symbols of wisdom. Bare feet and monks cloak represents asceticism. Often The Buddha has a nimbus or halo around his head, expressing enlightenment. When The Buddha touches the ground it is a sign of compassion.

Important features and symbols on a Buddha statue (See the Picture): 1) The Bump of Knowledge at the top of the head, symbolizing spiritual wisdom or accumulated wisdom reached at a higher spiritual level (The bump is often covered by curls of hair symbolizing enlightenment); 2) The Jewel, radiating the light of wisdom; 3) curly hair, representing enlightenment, is said to represent the stubble left on Gautama Siddhartha’s head after he cut off his hair, according to one legend, by pulling his hair together into a top knot and lopping it off, leaving fine curls (spiraling to the right) that never needed cutting again;

4) The all-seeing spiritual third eye, in middle of forehead; which appears on all Buddha statues, from which rays of light are emitted to enlighten the world (the eye is often represented with a crystal or gemstone; 6) The Robe stitched from rags in manner used by early monks; 7) mudras, hand positions, (see below); 8) halo, representing the magnificent light radiating from the Buddha; 8) leg position, here we see the cross-legged Lotus Position, one of three basic poses, which shows The Buddha "grew" out of the "mud" of the material world like a beautiful lotus, which grows out of the mud at the bottom of a pond.

Buddhist Art: Buddhist Symbols viewonbuddhism.org/general_symbols_buddhism ; Wikipedia article on Buddhist Art Wikipedia ; Asian Art at the British Museum britishmuseum.org; Buddhism and Buddhist Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org ; Buddhist Art Huntington Archives Buddhist Art dsal.uchicago.edu/huntington ; Buddhist Art Resources academicinfo.net/buddhismart ; Buddhist Art, Smithsonian freersackler.si.edu ; Asia Society Museum asiasocietymuseum.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS:

“How to Read Buddhist Art” (The Metropolitan Museum of Art - How to Read)

by Kurt A. Behrendt Amazon.com ;

“Reading Buddhist Art: An Illustrated Guide to Buddhist Signs and Symbols” by Meher McArthur Amazon.com ;

“The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs” by Robert Beer Amazon.com;

“The Tibetan Iconography of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, and Other Deities: A Unique Pantheon” by Lokash Chandra and Fredrick W. Bunce Amazon.com

“Buddhist Art: An Historical and Cultural Journey” by Giles Beguin Amazon.com ;

“Tree & Serpent: Early Buddhist Art in India” by John Guy Amazon.com ;

“Early Buddhist Narrative Art: Illustrations of the Life of the Buddha from Central Asia to China, Korea and Japan” by Patricia E. Karetzky Amazon.com;

“Pilgrimage and Buddhist Art” by Adriana Proser, Susan Beningson Amazon.com ;

“Buddhist Art and Architecture” by Robert E. Fisher Amazon.com ;

“Buddhist Architecture” by Le Huu Phuoc Amazon.com ;

“The Buddhist Art of China” by Zhang Zong Amazon.com;

“Cave Temples of Dunhuang: Buddhist Art on China’s Silk Road”

by Neville Agnew, Marcia Reed, et al.

Amazon.com;

“Cave Temples of Mogao at Dunhuang: Art and History on the Silk Road”

by Roderick Whitfield, Susan Whitfield, et al Amazon.com;

Superhuman and Life Symbols on Buddha Images

Vidya Dehejia, a professor at Columbia University, wrote: “The Buddha is usually portrayed wearing a monastic robe draped so as to cover both shoulders or to leave the right shoulder bare. The Buddha is said to have had thirty-two marks of superhuman perfection. The ushnisha, a cranial bump that signifies his divine knowledge, was transformed by artists into a hair knot, while the urna, a tuft of hair between the eyebrows, was depicted as a rounded mark. Elongated earlobes, indicating divine or elevated status, are given not only to the Buddha but also to all Hindu and Jain deities and to saintly figures. Images of the Jain tirthankaras (jinas) are similar to the Buddha; however, they have a shrivatsa emblem on the chest, are often unclothed, and do not have the ushnisha or urna.” [Source: Vidya Dehejia, Department of Art History and Archaeology, Columbia University Metropolitan Museum of Art]

Among the 32 signs of a “superhuman” (“mahopurusha” ) are: 1) a wisdom bump (“ushnisha” ), a cranial bump covered by top knot of hair representing omniscience, also associated with ancient Indian wandering ascetics; 2) a small tuft of hair (“urna” ), or dot between the eyebrows, symbolizing renunciation. Other superhuman signs include elongated ears, antelope-like legs, skin so smooth that dust doesn’t collect on it, intensely black eyes, cow-like eyelashes, 40 teeth, sheath-cloaked genitals, raised palm (the boon-granting gesture), and long and straight toes. [Diagram and information in the picture on the right is from sotozen-net.or.jp and onmarkproductions.com For a more detailed look at a Japanese Buddha statue see onmarkproductions.co ]

Each of the episodes of Buddha’s life have their own distinctive symbols. After The Buddha achieved enlightenment, for example, he was surrounded by a six-Lord aura that was 20 feet in diameter. After he meditated for another several weeks his aura was invaded by the serpent king Mucalinda, who. opened its hood and wound its coils seven times around The Buddha to protect him from a rain storm.

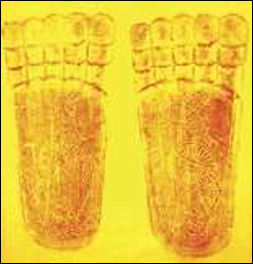

Buddha Footprints and Teeth

There are acknowledged to be only two genuine Buddha's teeth in existence, one in China and the other in Sri Lanka. Buddhists believe the teeth, reportedly found after Buddha was cremated 2,400 years ago, bring peace and good fortune.

Carved footprints called “buddhapada” are among the oldest-known works of Buddhist art and faith, with the oldest examples from the A.D. 1st century Gandhara in Pakistan. One such piece carved in grey stone has a pair of truth wheels on each meter-long foot. Smaller ones have been carved on lapis lazuli seals less then two centimeters in length.

Footprints of The Buddha are important objects of veneration, both in terms of purported footprints left behind by the historical Buddha and representations of his footprints. Because they seem to convey his presence without him actually being there footprints have came to represent transcendental power. Footprints are both representations of the Buddha’s presence and absence, and loss and recovery. They are images that are easy to identify with. In ancient times, footprints and hand prints were regarded as the physical touch of Buddha and other major religious figures. The Buddha himself said, “Creatures without feet have love, / And likewise those that have two feet / And those that have four feet I love, / And those, too, that have many feet.”

A footprint was chosen as representative of The Buddha because it expressed humility and addressed the fear that his image might be worshiped. On footprints, The Buddha is reported to have said: “In the future, intelligent being will see the scriptures and understand. Those of less intelligence will wonder whether The Buddha appeared in the world. In order to remove the doubts. I have set my footprints in stone.”

Carved footprints was supposed to be imprinted with 108 auspicious symbols. The hand or palm of The Buddha is an important symbol. In Tibet, footprints and to a lesser degree handprints of revered lamas appear on thangkas. They are often placed next to the subject’s patron deity or an image of the lama himself. The handprints often look like handprints in prehistoric caves or the ones at Grauman’s Chinese Theater.

Postures of the Buddha in Buddhist Art

The four postures of the Buddha found in Buddhist art,: 1) sitting, 2) reclining, 3) standing, and 4) walking. The most common of these by far is the seated Buddha. Walking Buddhas are pretty rare. The walking Buddha is either beginning his journey toward enlightenment or returning from teaching a sermon.

five most common mudra positions of seated Buddhas

The sitting Buddha is often teaching or meditating. Exactly what he is all about can be surmised from the mudras, or hand positions. The reclining Buddha is in the final stage of earthly life, before reaching nirvana-after-death. The standing Buddha is rising to teach after reaching nirvana.

A stone standing Buddha from Burma from the second half of 7th century is a traditional frontal and static one with identifying marks and mudras derive from Indian models, yet his facial type and proportions have been altered to satisfy local tastes. The face is almost heart-shaped, with a broad forehead, wide eyes, long nose, upturned mouth, square jaw, and small chin. The unusually large head, the wide shoulders and hips, and the tapering legs have lost a close correspondence with the human form. Attention is drawn to the Buddha’s expression by the crisp patterns of his hair, which contrast with the otherwise smooth and simplified shapes.[Source: Steven M. Kossak and Edith W. Watts, The Art of South, and Southeast Asia, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York]

The ovals of his head and rounded cheeks are repeated in the volumes of the shoulders, chest, and thighs. The Buddha’s monastic robes cling to his body as if they were transparent, revealing the belt of the under-robe and his robust upper body. The outer robe, devoid of folds, flares outward beneath his arms in a flat plane from which the upper body projects as if in high relief.

Reclining Buddhas

David Wilson wrote in The Star, a Malaysian newspaper: “Traditional reclining Buddhas have the left arm aligned along the body while the right serves as a pillow with the hand propping the head. Sometimes no longer than a grain of rice, the reclining Buddha is more often on the scale of a large boat. The icon appears mirage-like everywhere, from Penang and Bangkok to Yangon in Burma... The reclining Buddha’s “home” may be a temple, grotto or fresco — anywhere with a touch of width and mystique. [Source: David Wilson. The Star, August 15, 2009]

The statue represents Shakyamuni Buddha — the historical Buddha — at his death at 80. It is said that when the Buddha knew the end was near, he asked his disciples to prepare a couch for him in a grove, then reclined on his right side, facing west, with his head propped on his hand. On the last day of his life, instead of just turning ashen, he kept teaching. So, despite their decadent aura, the statues embody — as it turns out — the devotion to duty that the Buddha displayed at the last gasp. Since the Buddha's complete enlightenment occurred immediately after "Calling the Earth Goddess to Witness" and since enlightenment takes place within the body without necessarily any outward indication, the iconographic position of "Calling the Earth to Witness" has come to be accepted as representing the enlightenment of the Buddha. To enhance this association, the cranial protuberance (usnisha = cosmic consciousness or supramundane wisdom) and the enigmatic "smile of enlightenment" were also employed. “

“Images of The Buddha seated in bhumisparsa mudra have been endlessly replicated in the art of Southeast Asia because it is a reminder to all mankind that there is a way to end human suffering. Therefore, as such, the creation of every additional image of the Buddha is a meritorious act that improves the donor's karma. The multiple images of this event stamped on clay votive plaques evidence the zeal of ancient donors who at times created forty or even one hundred images of the Buddha with a single impression of a metal mould. Because of the large number of Buddha images, these plaques were thought to be especially efficacious in assuring the ritual purity and power of a specific site and, therefore, were often placed in underground chambers below the center-most point of the sanctum in a Buddhist building.” =

Buddha under the Bodhi Tree, Pagan

Another bewitching but spectacular reclining Buddha occupies Chaukhtatgyi Temple in Burma’s capital, Yangon. It boasts what resembles heavy makeup, a shimmering golden robe and huge feet. It is squeezed into an open-sided, steel-and-corrugated iron structure. A 200 meter statue is believed to be hidden under the earth in Bamiyan, central Afghanistan, near the ruins of the two large standing Buddhas destroyed in 2001 by the Taliban.

There are several very large reclining Buddha’s in Myanmar. The Burmese like their reclining Buddhas to be sensational. The hollow reclining one in Monywa, central Burma, which you can walk through, stretches 90m and is acclaimed as the world’s largest. A stone reclining Buddha being carved in east China’s Jiangxi Province will reportedly stretch 416m — the length of an oil tanker. However dazzled you may be by the grandeur and glamour, just remember one thing: do not to fall into the trap of referring to any reclining Buddha as “sleeping”. True, the Buddha, being human, took nightly downtime like anyone else. But his name means “The Awakened”.

But two puzzles remain. The first is the smile that plays on the lips, which may seem odd especially to anyone familiar with the reality of death or Christian images of wretched saints and angels. The smile, it transpires, is simply meant to express “the supreme joy” that comes with enlightenment, Gach explains. The reclining Buddha at Gal Vihara in Sri Lanka measures 14m in length while the upright one is 7m high. The Buddha knew that he was not destined for everyday death but “parinirvana” — a state defined as “the extinction of the endless round of illusion and needless suffering”.

The second puzzle is the typically extravagant size, which may seem outrageous to anyone familiar with Christian statues or the Buddhist emphasis on moderation. This time, the explanation is less simple, with roots in a legend that has a Freudian fairytale feel. The legend centres on a giant called Asurindarahu, who had more pride than a NBA megastar. When confronted with an opportunity to meet the Buddha, the giant was torn. On one hand, he yearned to see the Buddha. On the other, because he was equipped with an ego on par with his epic proportions, he was loath to bow before him, the story goes.

So, while lying down, the Buddha engaged in magic, projecting an image of himself that dwarfed the giant. The Buddha then showed him the realm of heaven populated by a multitude of celestial figures that were smaller than the Buddha but, again, dwarfed the giant. Just to rub it in, the Buddha commented that the giant was only a big fish in a small pond. Humiliated by the lecture and the awesome display of soft power, Asurindarahu duly kowtowed, even cringing “like a spider clinging to the hem of his robes”.

The size and splendour of reclining Buddha statues may make the traveller feel humbled, too. In particular, the reclining Buddha that graces Bangkok’s Wat Pho is tremendously imposing, all the more so because its feet and eyes are engraved with mother-of-pearl. Equally impressive is the reclining Buddha at Shanghai’s Jade Buddha Temple, which is carved from a single chunk of jade almost two meters in length.

Another bewitching but spectacular reclining Buddha occupies Chaukhtatgyi Temple in Burma’s capital, Yangon. It boasts what resembles heavy makeup, a shimmering golden robe and huge feet. It is squeezed into an open-sided, steel-and-corrugated iron structure. A 200 meter statue is believed to be hidden under the earth in Bamiyan, central Afghanistan, near the ruins of the two large standing Buddhas destroyed in 2001 by the Taliban.

There are several very large reclining Buddha’s in Myanmar. The Burmese like their reclining Buddhas to be sensational. The hollow reclining one in Monywa, central Burma, which you can walk through, stretches 90m and is acclaimed as the world’s largest. A stone reclining Buddha being carved in east China’s Jiangxi Province will reportedly stretch 416m — the length of an oil tanker. However dazzled you may be by the grandeur and glamour, just remember one thing: do not to fall into the trap of referring to any reclining Buddha as “sleeping”. True, the Buddha, being human, took nightly downtime like anyone else. But his name means “The Awakened”.

reclining Buddha at Gal Vihara in Sri Lanka

Mudras

Mudras are sacred hand gestures. In Buddhism they can commonly be seen in statues and other images of the Buddha and bodhisattvas and convey the presence of the divine and express a particular meaning. They can be the focus of meditation and are also present in Hindu art and Indian classical dance. Among the most common Buddhist mudras are the 1) the meditative pose, with cupped hands resting on the lap; 2) the protection pose, with the right hand raised; 3) the teaching pose, with one hand raised and the index finger touching the thumb of the same hand. 4) If a Buddha holds a wheel of dharma in his left hand and a scripture in the right hand its signifies he is a good teacher. 5) Touching the ground symbolizes a call to Mother Earth to witness his defeat of Mara as well as compassion.

Mudras are a means communication and self-expression, consisting of hand gestures and finger-postures and are used to evoke in the mind ideas symbolizing divine powers or deities themselves. The can be seen as a highly stylized form of body or hand language. Many such hand positions are found the Buddhist sculpture and painting of India, Tibet, China, Korea and Japan. They indicate to the faithful in a simple way the nature and the function of the images represented. Mudras symbolize divine manifestation and are also used by monks when meditated to improve concentration and tape into forces invoked by a Buddha or deity image. [Source:Lotussculpture.com]

Mudras can be the focus of Buddhist ritual or give meaning a sculptural image, a dance movement, or a meditative pose, intensifying their potency. In their highest forms, they can become magical, symbolical gestures through which invisible forces may operate on the earthly realm. Another layer of meaning is revealed by the five fingers. Each of the fingers, starting with the thumb, is identified with one of the five elements:sky, wind, fire, water, and the earth. Their contact with each other symbolizes the union of these elements and the power they evoke. This contact between the various elements creates conditions favorable for the presence of the deity at rites performed for securing some desired result.

Mudras are not the exclusive domain of Buddha; they can also be employed by ordinary people in everyday life. The yoga of mudra is a deliberate and intended arrangement of the body or parts of the body aimed at harmonizing the physiological system of the body with the cosmic forces of the universe. In some respects we perform mudras in every action, every moment of the day. Each action is a symbol of our underlying mental and physical conditions. Consciously performing mudras allow us to become more aware of inner energy and to control it so that we make the most of each moment.

Different Mudra

Vitarka Mudra is the Intellectual Argument, Debate, Appeasement Mudra. The gesture of discussion and debate, it indicates communication and projection of the Dharma. The tips of the thumb and index finger touch, forming a circle. All other fingers are extended upwards. Sometimes the middle finger and thumb touch, which is gesture of great compassion. If the thumb and ring finger touch, they express the mudra of good fortune. [Source:Lotussculpture.com]

Anjali Mudra conveys respect and worship. It is made by placing the palms of the hand and fingers flat together, often before the heart. Sometimes the head is slightly bowed. This gesture can be found in Buddhism, Hinduism, and Christianity. Statues of the bodhisattvas may display the anjali mudra. Hindus use this gesture in greeting, while Christians may position their hands in this fashion when they pray. [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

Varada Mudra is the Wish-Granting Mudra and stands for compassion and charity. Often performed at the same time as the abhaya (fearlessness) mudra, it is usually made with the left hand, with the arm hanging naturally at the side, the open palm facing forward, and fingers extended. The extended fingers represent the five perfections: generosity, morality, patience, effort, and meditative concentration. This mudra . [Source: Encyclopedia.com]

The Varada mudra expresses the wish to devote oneself to human salvation. It is nearly always made with the left hand, and can be made with the arm hanging naturally at the side of the body, the palm of the open hand facing forward, and the fingers extended. The five extended fingers in this mudra symbolize the following five perfections: 1) Generosity, 2) Morality, 3) Patience, 4) Effort and 5) Meditative Concentration. This mudra is rarely used alone, but usually in combination with another made with the right hand, often the Abhaya mudra (described below). This combination of Abhaya and Varada mudras is called Segan Semui-in or Yogan Semui-in in Japan.

Bhumisparsha Mudra is the Earth Touching Mudra, calling the Earth to Witness, or The Victory Over (Subduing) Mara Literally Bhumisparsha translates into 'touching the earth'. It is more commonly known as the 'earth witness' mudra. This mudra, formed with all five fingers of the right hand extended to touch the ground, symbolizes the Buddha's enlightenment under the bodhi tree, when he summoned the earth goddess, Sthavara, to bear witness to his attainment of enlightenment. The right hand, placed upon the right knee in earth-pressing mudra, and complemented by the left hand-which is held flat in the lap in the dhyana mudra of meditation, symbolizes the union of method and wisdom, samasara and nirvana, and also the realizations of the conventional and ultimate truths. It is in this posture that Shakyamuni overcame the obstructions of Mara while meditating on Truth. The second Dhyani Buddha Akshobhya is depicted in this mudra. He is believed to transform the delusion of anger into mirror-like wisdom. It is this metamorphosis that the Bhumisparsha mudra helps in bringing about.

Buddha of Medicine holds a medicine box in his left hand and makes a devil-expelling gesture with his right hand. Symbolic objects found on Bodhisattvas and deities include swords used to cut down disruptive passions and desires; cords used to pull wayward people back to the correct path.

Teaching Mudra

The Dharmachakra Mudra is Teaching, Preaching or Wheel-Turning, Mudra. It is formed by touching together the tips of the thumb and index finger on both hands. The circle made by this positioning represents the Dharma Wheel. The hands are held in front of the heart to show that the teachings are from the Buddha's heart. This mudra symbolizes the occasion of the Buddha's first sermon after he achieved enlightenment. [Source:Lotussculpture.com, Encyclopedia.com]

Dharmachakra in Sanskrit means the 'Wheel of Dharma'. This mudra symbolizes one of the most important moments in the life of Buddha, the occasion when he preached to his companions the first sermon after his Enlightenment in the Deer Park at Sarnath. It thus denotes the setting into motion of the Wheel of the teaching of the Dharma. In this mudra the thumb and index finger of both hands touch at their tips to form a circle. This circle represents the Wheel of Dharma, or in metaphysical terms, the union of method and wisdom.

The three remaining fingers of the two hands remain extended. These fingers are themselves rich in symbolic significance:The three extended fingers of the right hand represent the three vehicles of the Buddha's teachings, namely: 1) The middle finger represents the 'hearers' of the teachings. 2) The index finger represents the 'realizers' of the teachings. 3) The little finger represents the Mahayana or 'Great Vehicle'. The three extended fingers of the left hand symbolize the Three Jewels of Buddhism, namely, the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha. Significantly, in this mudra, the hands are held in front of the heart, symbolizing that these teachings are straight from the Buddha's heart.

Meditation Mudra

The Dhyana Mudra is the Meditation Mudra. There are two different forms and they may be made with one or both hands. When the left hand is resting in the lap and the right hand is in another position, the dhyana mudra represents wisdom. When both hands are in dhyana mudra, they are usually resting at the level of the stomach or thighs, with the right hand above the left, palms facing upward, and fingers extended. In some instances, the thumbs of the two hands will touch the fingertips. This mudra is one of meditation and concentration. [Source:Lotussculpture.com, Encyclopedia.com]

When made with a single hand the left hand symbolizes the female left-hand principle of wisdom. Ritual objects such as a text, or more commonly an alms bowl symbolizing renunciation, may be placed in the open palm of this left hand. When made with both hands, the hands are generally held at the level of the stomach or on the thighs. The right hand is placed above the left, with the palms facing upwards, and the fingers extended. In some cases the thumbs of the two hands may touch at the tips, thus forming a mystic triangle. The esoteric sects obviously attribute to this triangle a multitude of meanings, the most important being the identification with the mystic fire that consumes all impurities. This triangle is also said to represent the Three Jewels of Buddhism, mentioned above, namely the Buddha himself, the Good Law and the Sangha.

The Dhyana mudra is the mudra of meditation, of concentration on the Good law, and of the attainment of spiritual perfection. According to tradition, this mudra derives from the one assumed by the Buddha when meditating under the pipal tree before his Enlightenment. This gesture was also adopted since time immemorial, by yogis during their meditation and concentration exercises. It indicates the perfect balance of thought, rest of the senses, and tranquility. This mudra is displayed by the fourth Dhyani Buddha Amitabha, also known as Amitayus. By meditating on him, the delusion of attachment becomes the wisdom of discernment. The Dhyana mudra helps mortals achieve this transformation.

Protection Mudra

The Abhaya Mudra represents fearlessness. It is made by raising the right hand to the shoulder, with the palm of the hand facing outward and the fingers extended straight and together. The arm is crooked, with the palm of the hand facing outward, and the fingers upright and joined. The left hand hangs down at the side of the body. The abhaya mudra is meant to eliminate fear and provide peace, protection, reassurance and blessing. Abhaya in Sanskrit means dispelling of fear. In Thailand, and especially in Laos, this mudra is associated with the movement of the walking Buddha (also called 'the Buddha placing his footprint'). It is nearly always used in images showing the Buddha upright, either immobile with the feet joined, or walking. [Source:Lotussculpture.com, Encyclopedia.com]

This mudra, which initially appears to be a natural gesture, was probably used from prehistoric times as a sign of good intentions - the hand raised and unarmed proposes friendship, or at least peace; since antiquity, it was a plain way of showing that you meant no harm since you did not carry any weapon. Buddhist tradition has an interesting legend behind this mudra: Devadatta, a cousin of the Buddha, through jealousy caused a schism to be caused among the disciples of Buddha. As Devadatta's pride increased, he attempted to murder the Buddha. One of his schemes involved loosing a rampaging elephant into the Buddha's path. But as the elephant approached him, Buddha displayed the Abhaya mudra, which immediately calmed the animal.

Accordingly, it indicates not only the appeasement of the senses, but also the absence of fear. The Abhaya mudra is displayed by the fifth Dhyani Buddha, Amoghasiddhi. He is also the Lord of Karma in the Buddhist pantheon. Amoghasiddhi helps in overcoming the delusion of jealousy. By meditating on him, the delusion of jealousy is transformed into the wisdom of accomplishment. This transformation is hence the primary function of the Abhaya mudra.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Kalachakranet.org, Simha.com; onmarkproductions.com

Text Sources: Metropolitan Museum of Art, Asia for Educators, Columbia University; Asia Society Museum “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World's Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); BBC, Wikipedia, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024