FIRE BOMBING ATTACKS ON JAPAN IN WORLD WAR II

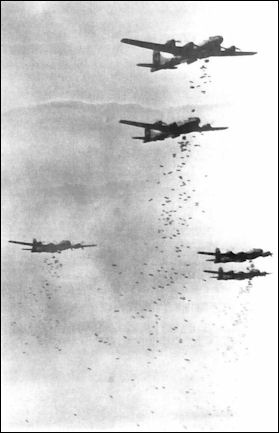

B-29s

In the spring and summer of 1945, the U.S. Army Air Forces destroyed nearly every major city in Japan. The early raids were daytime, high-altitude bombing runs with many bombs missing their mark. Later the tactic was changed to low-flying, night-time raids that utilized hundreds of B-29 bombers that dropped bombs with napalm and other incendiary chemicals.

From January 1944 to August 1945, the U.S. dropped 157,000 tons of bombs on Japanese cities, according to the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey. The death toll from the bombings is estimated at more than 300,000, while another 15 million were left homeless. The firebombing of central Tokyo, killed more than 100,000 people and left hundreds of thousands more homeless. Cities in which more than 2,000 people were killed in air raids included Tokyo, Yokohama, Toyama, Shizuoka, Hamanmatsu, Nagoya, Osaka, Kobe, Kure, Kitakyushi and Kagoshima. [Source: Associated Press, December 10, 2015]

In preparation for the attacks, Americans built small Japanese villages at the Duqay Proving Ground in Utah in 1943, complete with straw tatami mats, to see how easily they burned. “The panic side of the Japanese is amazing,” one intelligence officer reported at a planning meeting. Fire “is one of the great things they are terrified at from childhood,” he said.

Tokyo-bases writer Takeyama Michio wrote: “Against the winter we tilled the fields assiduously. But nothing much grew. It was the third or forth time that B-29s had appeared in the skies over Tokyo. In the clear early winter air, they floated calmly, violet and sparkling. Shining like a firework, a Japanese plane approached like a shooting star and rammed a B-29. Then, spinning and giving off black smoke, it fell to earth. Drawing long white frosty lines, the B-29s faded slowly into the crystalline distance.”

Bombing of civilian targets was done by most of the participants in World War II. According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “For the first time outside a civil war, fighting spread beyond the armies to whole populations: Hitler used aerial bombing to try to break the spirit of the British; the Japanese used aerial bombing and soldiers against the Chinese civilian population; both Japan and Germany used their military forces to subdue resistance in occupied nations; and the allied forces used bombing to carry the war beyond the battle front and break the opposition of enemy populations. By the end of the war, technology had advanced to the point where such bombings were terrible: the allied bombing of Dresden killed tens of thousands of people, and the American firebombing of Tôkyô in March 1945 probably killed more than 100,000 people. During this period, wartime technology raced ahead, as each side attempted to be the first to develop the techniques and equipment that would enable it to win. Many nations sought to decipher the secrets of atomic energy, but the United States was the first to develop the ultimate weapon, the atomic bomb.” [Source: Asia for Educators Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: OKINAWA, KAMIKAZES, HIROSHIMA AND THE END OF WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; IWO JIMA AND THE DRIVE TOWARD JAPAN factsanddetails.com; BATTLE OF OKINAWA factsanddetails.com; SUFFERING BY CIVILIANS DURING THE BATTLE OF OKINAWA factsanddetails.com; KAMIKAZES AND HUMAN TORPEDOES factsanddetails.com; KAMIKAZE PILOTS factsanddetails.com; DEVELOPMENT OF ATOMIC BOMBS USED ON JAPAN factsanddetails.com; DECISION TO USE TO ATOMIC BOMB ON JAPAN factsanddetails.com; ATOMIC BOMBING OF HIROSHIMA AND NAGASAKI factsanddetails.com; SURVIVORS AND EYEWITNESS REPORTS FROM HIROSHIMA AND NAGASAKI factsanddetails.com; HIROSHIMA, NAGASAKI AND SURVIVORS AFTER THE ATOMIC BOMBING factsanddetails.com; JAPAN SURRENDERS, THE USSR GRABS LAND AND JAPANESE SOLDIERS WHO DIDN'T GIVE UP factsanddetails.com; APOLOGIES, LACK OF APOLOGIES, JAPANESE TEXTBOOKS, COMPENSATION AND WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; LEGACY OF THE ATOMIC BOMBING OF JAPAN AND OBAMA'S VISIT TO HIROSHIMA factsanddetails.com; LEGACY OF WORLD WAR II IN JAPAN factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Black Snow: Curtis LeMay, the Firebombing of Tokyo, and the Road to the Atomic Bomb” by James M. Scott Amazon.com; “Mission to Tokyo: The American Airmen Who Took the War to the Heart of Japan” by Robert F. Dorr Amazon.com; “Inferno: The Fire Bombing of Japan, March 9 - August 15, 1945" by Edwin P. Hoyt Amazon.com; “Japan 1944-45: LeMay’s B-29 strategic bombing campaign” by Mark Lardas , Paul Wright, et al. Amazon.com;

Doolittle and the First Firebombing Raid on Japan

The first bombing raid on Japan in April, 1942 was masterminded by flyer James Doolittle, a famous 5-foot 4-inch American flyer who set many speed records and pioneered the art of instrument flying. The mission, one the riskiest ever conceived, was to launch 16 fully-loaded Mitchell B-25 bombers from an aircraft carrier (the first time this was ever tried), fly to Japan and drop their payload of three 500-pound bombs, and then continue on to China where they hoped they had enough fuel to take them to friendly territory. [Source: James A. Cox, Smithsonian magazine]

The B-25 Mitchells usually took off at about 95 mph from a 1000-foot-long airstrip. On the aircrafts carrier they would have to take off at 45mph from a deck less than 500 feet long. Parts of the plane were removed to reduce weight and the gas tanks were enlarged to increase the range. The 80 crew members that took part in the mission were briefed that Orientals who grinned were Japanese and those who grinned and smiled were Chinese.

Doolittle Plane takes off

The planes took off a day ahead of schedule on April 18, 1942 because the carrier that carried them was spotted by a Japanese vessel. Before they took off the planes were rocked back and forth to get rid of air bubbles which would allow the planes to take on more fuel. The only mishap occurred when one crew member was blown into a propeller and his arm was cut off. In 60 minutes all the planes were in the air. They kept their radios turned off to avoid detection.

The planes reached Japan and dropped their high-explosive bombs on dry docks, ships, arsenals, oil refineries and aircraft factories in Tokyo, Yokohama, Nagoya, Osaka and Kobe and then fled south. They encountered little anti-aircraft fire and only one Zero followed in pursuit. The Japanese plane was lost during low altitude evasive maneuvers; there were no casualties and only one plane was hit by flak. the whole operation was over in minutes but he hard part of mission had yet to begin.

After thirteen hours in the air the planes found themselves in darkness and clouds somewhere over China or the Sea of China, running dangerously low on fuel. The only plane that landed safety was one that veered north to Vladivostok, Russia. Of the remaining 15 planes, four crash landed. The crew from other 11 planes parachuted. Doolittle landed in a rice paddy full of night soil. Of the eight crew members who were captured by the Japanese, five were executed and three were sent to prison (where one died of malnutrition). The other 72 men miraculously made it safety, although one them had his face smashed and his arm amputated after the crash.

The bombing raid was mainly a psychological ploy to show that Japan was vulnerable to attack. One newspaper in America ran the headline "TOKYO BOMBED! DOOLITTLE DO'OD IT!" The Japanese were so shaken they launched an attack on the airbases in China, where the pilots had hoped to land. When the dust settled thousands of Chinese were dead.

Eyewitness Account of Doolittle Raid

Describing the take off of Doolittle’s plane, Lt. Ted Lawson, who piloted one of the attacking bombers, wrote: "A Navy man stood at the bow of the ship, and off to the left, with a checkered flag in his hand. He gave Doolittle, who was at the controls, the signal to begin racing his engines again. He did it by swinging the flag in a circle and making it go faster and faster. Doolittle gave his engines more and more throttle until I was afraid that he'd burn them up. A wave crashed heavily at the bow and sprayed the deck.[Source: “Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo “ by Ted W. Lawson, 1943, reprinted 1953]

“Then I saw that the man with the flag was waiting, timing the dipping of the ship so that Doolittle's plane would get the benefit of a rising deck for its take-off. Then the man gave a new signal. Navy boys pulled the blocks from under Doolittle's wheels. Another signal and Doolittle released his brakes and the bomber moved forward. With full flaps, engines at full throttle and his left wing far out over the port side of the Hornet, Doolittle's plane waddled and then lunged slowly into the teeth of the gale that swept down the deck. His left wheel stuck on the white line as if it were a track. His right wing, which had barely cleared the wall of the island as he taxied and was guided up to the starting line, extended nearly to the edge of the starboard side.

We watched him like hawks, wondering what the wind would do to him, and whether we could get off in that little run toward the bow. If he couldn't, we couldn't. Doolittle picked up more speed and held to his line, and, just as the Hornet lifted itself up on the top of a wave and cut through it at full speed, Doolittle's plane took off. He had yards to spare. He hung his ship almost straight up on its props, until we could see the whole top of his B-25. Then he leveled off and I watched him come around in a tight circle and shoot low over our heads-straight down the line painted on the deck."

On the attack on his bomb target in Tokyo, Lawson wrote: "I was almost on the first of our objectives before I saw it. I gave the engines full throttle as Davenport [co-pilot] adjusted the prop pitch to get a better grip on the air. We climbed as quickly as possible to 1,500 feet, in the manner which we had practiced for a month and had discussed for three additional weeks. There was just time to get up there, level off, attend to the routine of opening the bomb bay, make a short run and let fly with the first bomb. The red light blinked on my instrument board, and I knew the first 500-pounder had gone.

Our speed was picking up. The red light blinked again, and I knew Clever [bombardier] had let the second bomb go. Just as the light blinked, a black cloud appeared about 100 yards or so in front of us and rushed past at great speed. Two more appeared ahead of us, on about the line of our wingtips, and they too swept past. They had our altitude perfectly, but they were leading us too much. The third red light flickered, and, since we were now over a flimsy area in the southern part of the city, the fourth light blinked. That was the incendiary, which I knew would separate as soon as it hit the wind and that dozens of small fire bombs would molt from it.

The moment the fourth red light showed I put the nose of the Ruptured Duck into a deep dive. I had changed the course somewhat for the short run leading up to the dropping of the incendiary. Now, as I dived, I looked back and out I got a quick, indelible vision of one of our 500-pounders as it hit our steel-smelter target. The plant seemed to puff out its walls and then subside and dissolve in a black-and-red cloud. . . Our actual bombing operation, from the time the first one went until the dive, consumed not more than thirty seconds."

Crash Landing off China After Doolittle Raid

About 6 ½ hours of leaving Tokyo Lawson's plane is low on fuel as the crew spots the Chinese mainland. Describing his attempts to land on a beach in a driving rain, Lawson wrote: "So I spoke into the inter-phone and told the boys we were going down. I told them to take off their chutes, but didn't have time to take off mine, and to be sure their life jackets were on, as mine was. I put the flaps down and also the landing wheels, and I remember thinking momentarily that if this was Japanese occupied land we could make a pretty good fight of it while we lasted. Our front machine gun was detachable. [Source: “Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo “ by Ted W. Lawson, 1943, reprinted 1953]

“Davenport was calling off the airspeed. He had just said, 'One hundred and ten,' when, for some reason I'll never understand, both engines coughed and lost their power.In the next split second my hands punched forward and with one motion I hit both throttles, trying to force life back into the engines, and both prop pitch controls. And I tried to pull back the stick to keep the nose up, so we could squash in. We were about a quarter of a mile off shore when we hit.

The two main landing wheels caught the top of a wave as the plane sagged. And the curse of desperation and disappointment that I instinctively uttered was drowned out by the most terrifying noise I ever heard. It was as if some great hand had reached down through the storm, seized the plane and crunched it in a closing fist. Then nothing. Nothing but peace. A strange, strange, peaceful feeling. There wasn't any pain. A great, restful quiet surrounded me.

Then I must have swallowed some water, or perhaps the initial shock was wearing off, for I realized vaguely but inescapably that I was sitting in my pilot's seat on the sand, under water. I was in about ten or fifteen feet of water, I sensed remotely. I remember thinking: I'm dead. Then: No, I'm just hurt. Hurt bad. I couldn't move, but there was no feeling of being trapped, or of fighting for air.

I thought then of Ellen [Cpt. Lawson's wife] - strange thoughts filled with vague reasoning but little torment. A growing uneasiness came through my numb body. I wished I had left Ellen some money. I thought of money for my mother, too, in those disembodied seconds that seemed to have no beginning or end. I guess I must have taken in more water, for suddenly I knew that the silence, the peace and the reverie were things to fight against. I could not feel my arms, yet I knew I reached down and unbuckled the seat strap that was holding me to the chair. I told myself that my guts were loose.

I came up into the driving rain that beat down out of the blackening sky. I couldn't swim. I was paralyzed. I couldn't think clearly, but I undid my chute. The waves lifted me and dropped me. One wave washed me against a solid object, and, after I had stared at it in the gloom for a while, I realized that it was one of the wings of the plane. I noticed that the engine had been ripped off the wing, leaving only a tangle of broken wire and cable. And with the recognition came a surge of nausea and despair, for only now did I connect my condition with the condition of the plane. Another wave took me away from the wing and when it turned me around I saw behind me the two tail rudders of the ship, sticking up out of the water like twin tombstones."

Napalm in Japan

The first use of napalm was in the fire bombing raids of Tokyo in 1945, when M-29 napalm bombs (bombs that burst at high altitude releasing hundred of smaller bombs) were dropped in flaming Xs, causing Japan’s wooden buildings to go up in flames, sometimes producing fire storms that lasted for days.

Napalm is a compound of jellied gasoline that sticks to anything it touches and burns at 3,000̊F. Invented by Harvard chemist Louis Fieser during World War II and named after its two principal ingredients, aluminum napthenate and coconut palm oil, it is made from an aluminum soap that thickens gasoline, making it burn slower and allowing it to ignite more secondary fires.

Napalm can be used in grenades, ariel bombs, artillery shells, missiles and tank cannons. It can be hurled at greater distances from flame throwers that other chemicals. Dropped from an airplane it can torch an area the size of a football field and destroy a tank without hitting it. Hurled into a tunnel it can suck up enough oxygen to suffocate anyone there.

Another effective fire-producing agents was jellied gasoline. Before World War II the most effective incendiary was rubber mixed with gasoline. After the Japanese seized the major rubber-producing regions the Allies were forced to come up with substitutes. The army liked napalm because it was easy to make and effective.

Fire Bombing of Japan

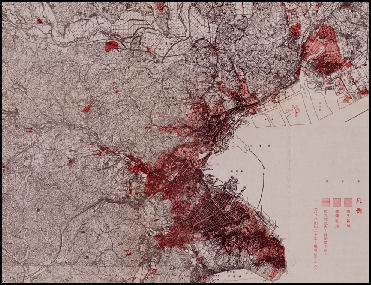

Map of damage to Yokohama Beginning in June, 1944, American B-29s launched from Tianan and Guam made daily fire bombing raids on Osaka, Tokyo, Yokohama, Kobe and several other Japanese cities. The first raid on June 15 used 47 B-29s to attack the Imperial Iron and Steel Works at Yawata. It was the first time American planes had entered Japanese airspace since the Doolittle raids in 1942.

More destructive than the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the raids destroyed more than 100 square miles of inhabited land, razed more than two million buildings, killed 500,000 people and left 13 million people homeless. "Blazing Tokyo Symbolizes Doom that Awaits Every Big Jap City," one Newsweek headline exclaimed.

Fire spread easily in Japanese cities because so many homes were made of wood. "Nights of strong wind were chosen and bombs were dropped windward in great quantity," wrote Japanese Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu in his memoirs. "The area encompassed by a wall of flame then became the target for the next wave...systematically bombing the whole city. The area became a sea of flames."

American pilots recall smelling burning human flesh during the conflagration. People that survived the fires often did so because their shelters had an entrance open to let heat escape while those that sought refuge in shelters with all the entrances closed were roasted alive. "Day by day, Japan turned into a furnace," Shigemitsu wrote. "And yet the clarion call was accepted. If the Emperor ordained it, they would leap into the flames."

Survivors of the Tokyo Fire-Bombing

Haruyo Nihei survived the March 10, 1945, firebombing of Tokyo. She was eight at the time and living in Tokyo' s downtown Shitamachi area. She fled with her family and watched as many others were burned alive. She told Associated Press that as the flames swept over her, she was sheltered both by her father, who survived, and by many others who had piled on top of them who suffocated or burned to death. Nihei's family all survived. They stayed with relatives and moved briefly to the countryside before eventually returning to their old neighborhood. She told Associated Press: "You know, those people who saved my life weren't anyone famous. But they did save my life. And those friends of mine who died who I used to play with, their stories would never be told if I don't tell them. Since I am a survivor, I feel I should help tell the story." [Source: Associated Press, March 9, 2015]

One survivor of the fire bombing of Tokyo told the Yomiuri Shimbun the air raids began after midnight. His father led his family to a river bank with his older siblings and mother carrying young family member of their backs. When they got to the river they realized some family members weren’t there and rushed back to the house to find it in flames with the children crying outside. Because of the flames they could not find there way back to the river and instead sought refuge in a small shelter near the house. “There was a fierce blaze swirling around us,” the survivor said. “The shelter got very hot but he managed to stay alive in part because strangers covered his body. When the dawn broke there were burned bodies everywhere. The survivor and his father went the river. There was no sign of his family other than the his mother’s padded coat found in a ditch.

George Bush Sr. Shot Down Near Tokyo

Twenty-year-old George Bush, the future U.S. president, was shot down near Chichi-Jima, a remote island near Iwo Jima in the middle of the Pacific about halfway between Japan and Guam, on September 2, 1944. Two of his crew mates were lost. He was rescued by a submarine. In a letter to his parents Bush wrote, "We got hit. The cockpit filled with smoke and I told the boys in the back to get their parachutes on. They didn't answer at all...I headed the plane out to sea and pulled on the throttle so we could away from land as much as possible. I am no clear about the next parts." [Source: Newsweek, March 15, 1999]

“I turned the plane up in attitude so as to take pressure off the back hatch so the boys could get out. After that I straightened up and started to get out myself...The cockpit was full of smoke and I was chocking from it. I glanced at the wings and noticed they were on fire...I stuck my head out first and the old wind really blew me the rest of the way out. As I left the plane my head struck the tail...There was no sign of Del or Ted anywhere around. I looked as I floated down and afterwards kept my eyes open from the raft, but to no avail...I sat in my raft and sobbed for awhile."

Curtis Le May and the Fire Bomb Strategy

Le May and Truman

General Curtis Le May is considered the father of the Fire Bomb Strategy. An ROTC graduate from Ohio State University, Le May advanced from the rank a major in 1941 to the youngest ever major general at the age of 37 in 1944. His fellow officers considered him cold and stoic but no one questioned his bravery. Nicknamed "Iron Ass," he said he expected to die in war and led every bombing mission he flew until he was grounded because he was considered too valuable to put at risk.

In Europe, Le May worked out that it was more efficient in terms of avoiding lost lives and hitting targets if bombers flew straight to their targets, dropped their payloads and returned than if they took evasive action against fighters and anti-aircraft fire. After his policy was implemented plane units hit twice as many targets as their predecessors. Le May was also responsible to developing a staggered formation that made it easier for Allied gunners to shoot German fighters without shooting other Allied planes.

Le May’s strategy was to “bomb and burn “em till they quit.” He once said, "I'll tell you what war is about. You've got to kill people, and when you've killed enough, they stop fighting." On another occasion he said, “I suppose if I had lost the war, I would have been tried as a war criminal. Fortunately, we were on the winning side.” He later raised the idea of nuking China and the Soviet Union and proposed firebombing villages in North Korea and nuking Vietnam during the wars in those countries. These actions earned him the title Gen. Jack D. Ripper.

Fire Bomb Strategy

Le May found that the B-29s used in Europe were not as effective in Japan because the consistent 200mph winds that blew at 35,000 feet over Japan made it almost impossible to hit targets. His solution was to fire bomb Japanese cities at night from a low altitude.

The planes flew at 5,000 feet but relatively few were shot down because the Japanese air force had nearly been obliterated when the fire bombing was conducted. at this point. By 1945 fewer American planes had were tied down in the Pacific and Europe. Japanese night defenses were much weaker than those of the Germans.

Le May used figures and charts to push forward the idea that relentlessly firebombing Japanese cities could prevent an Allied invasion. "Killing Japanese didn't bother him very much," Le May later said. "It was getting the war over that bothered me. So I wasn't particularly worried about how many people were killed in getting the job done.”

It was total war: an effort to defeat a country by annihilating it. There was no secret about what was going on. Newspapers reported the destruction and most Americans supported it. They seemed little concerned by the unprecedented loss of life in Japan.

Sixty-five cities were bombed by American planes. Of the six major cities bombed, 51 percent of Tokyo was destroyed as well as 56 percent of Kobe, 26 percent of Osaka, 31 percent of Nagoya, 33 percent of Kawasaki and 44 percent of Yokohama.

Junior high school students demolished wood houses and created firebreaks around government buildings. Many people dug shallow pits behind their homes that passed as bomb shelters. Kobe was bombed 25 times in the final year of World War II. The attacks left 17,014 dead and 530,858 homeless. One survivor of the Kobe earthquake said: "It looked like this. The difference is, we could hear the planes coming, but the earthquake was silent."

Crews that were shot down over Japanese soil were told to give themselves up to military authorities because nearly every Japanese civilian had been affected by the bombings or had lost a relative and very well might seek revenge against any downed flyer he encountered.

Intense Fire Bomb Attacks on Tokyo and Other Japanese Cities

Damage to Sendai

During a ten day period in March, 1945, the U.S. launched 11,600 B-29 firebomb raids that wiped out 32 square miles of Japan's four largest cities. In one massive all-night raid on Tokyo on March 10, 1945, involving more than 1,000 planes launched from bases on islands south of Japan, over 140,000 people were killed — 20,000 more than were killed at Hiroshima — a world record for conventional bombing. Despite the massive destruction Japan continued fighting.

One American pilot wrote in his diary, “Suddenly, way off at 2 o’clock, I saw a glow on the horizon like the sun rising or maybe the moon. The whole city of Tokyo was below us stretching from wingtip to wingtip, ablaze in one enormous fire with yet more fountains of flame pouring down from the B-29s. The black smoke billowed up thousands of feet, causing powerful thermal currents that buffeted our plane severely, bringing with it the horrible smell of burning flesh.”

In the raids on Tokyo 16 square miles of the city was burned to a crisp. A survivor of the raids told the Japan Times: "In 1944, I was in Tokyo when it was heavily bombed. But the next day we began to adjust to the new environment and find a way to survive. It's the gaman mind set, and it's in the national character of the Japanese people.” Future Prime Minister of Japan Junichiro Koizumi wrote, “Where the residences and shops of hundreds of thousands once stood, nothing — not a tree, not a building — could be found still upright. As my family’s home was among those burnt down, we fled to Yokohoma.”

The raids on Tokyo were called off in May, 1945 because there were virtually no major targets left. Even Le May admitted there was "no pint point in slaughtering civilians for the mere sake of slaughter.” Attacks on other cities continued through July. By that time all but five of Japan’s major cites had been attacked. Hundreds of thousands of civilians were dead.

Just before the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, a massive bombing attack was lunched on 67 cities. More than 100,000 lives were lost in a single night. On July 10, 1945, less than a month before the war ended, 900 tons of bombs, including 13,000 incendiary bombs were dropped on the city center of Sendai, killing 1,279 people. One survivor told the Daily Yomiuri she spent the night in a school where she worked when she want to check out the bomb shelter where here family was she say it was destroyed. Looking down a 30-centimeter hole she found her husband, and young daughter and son. They only suffered slight burns but were dead.

Eyewitness Account of the Tokyo Fire Bombing

Robert Guillain, a French reporter assigned to Japan in 1938 and trapped there after Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor, was in Tokyo on the night of March 9, 1945. In a book he published after the war he wrote: "They set to work at once sowing the sky with fire. Bursts of light flashed everywhere in the darkness like Christmas trees lifting their decorations of flame high into the night, then fell back to earth in whistling bouquets of jagged flame. Barely a quarter of an hour after the raid started, the fire, whipped by the wind, began to scythe its way through the density of that wooden city. [Sources: Eyewitness to History.com; “I Saw Tokyo Burning “ by Robert Guillain 1981; “ Blankets of Fire: US. Bombers over Japan During World War II “ by Kenneth Werrell, 1996]

“This time again, luck - or rather, the American command's methodical planning - spared my district from direct attack. A huge borealis grew over the quarters closer to the center, which had obviously been reached by the gradual, raid-by-raid unrolling of the carpet-bombing. The bright light dispelled the night and B-29s were visible here and there in the sky. For the first time, they flew low or middling high in staggered levels. Their long, glinting wings, sharp as blades, could be seen through the oblique columns of smoke rising from the city, suddenly reflecting the fire from the furnace below, black silhouettes gliding through the fiery sky to reappear farther on, shining golden against the dark roof of heaven or glittering blue, like meteors, in the searchlight beams spraying the vault from horizon to horizon. There was no question in such a raid of huddling blindly underground; you could be roasted alive before you knew what was happening. All the Japanese in the gardens near mine were out of doors or peering up out of their holes, uttering cries of admiration - this was typically Japanese - at this grandiose, almost theatrical spectacle.

The bombs were falling farther off now, beyond the hill that closed my horizon. But the wind, still violent, began to sweep up the burning debris beaten down from the inflamed sky. The air was filled with live sparks, then with burning bits of wood and paper until soon it was raining fire. One had to race constantly from terrace to garden and around the house to watch for fires and douse firebrands. Far-off torch clusters exploded and fell back in wavy lines on the city. Sometimes, probably when inflammable liquids were set alight, the bomb blasts looked like flaming hair. Here and there, the red puffs of antiaircraft bursts sent dotted red lines across the sky, but the defenses were ineffectual and the big B-29s, flying in loose formation, seemed to work unhampered. At intervals the sky would empty; the planes disappeared. But fresh waves, announced in advance by the hoarse but still confident radio voice, soon came to occupy the night and the frightful Pentecost resumed. Flames rose nearby - it was difficult to tell how near - toward the hill where my district ended. I could see them twisting in the wind across roofs silhouetted in black; dark debris whirled in the storm above me."

The bombers' primary target was the neighboring industrial district of the city. "Around midnight, the first Superfortresses dropped hundreds of clusters of the incendiary cylinders the people called "Molotov flower baskets," marking out the target zone with four or five big fires. The planes that followed, flying lower, circled and crisscrossed the area, leaving great rings of fire behind them. Soon other waves came in to drop their incendiaries inside the "marker" circles. Hell could be no hotter.

Nagoya Castle burning

Eyewitness Account of Tokyo Burning

Guillain wrote: The inhabitants stayed heroically put as the bombs dropped, faithfully obeying the order that each family defend its own home. But how could they fight the fires with that wind blowing and when a single house might be hit by ten or even more of the bombs, each weighing up to 6.6 pounds, that were raining down by the thousands. As they fell, cylinders scattered a kind of flaming dew that skittered along the roofs, setting fire to everything it splashed and spreading a wash of dancing flames everywhere - the first version of napalm, of dismal fame. The meager defenses of those thousands of amateur firemen - feeble jets of hand-pumped water, wet mats and sand to be thrown on the bombs when one could get close enough to their terrible heat were completely inadequate. Roofs collapsed under the bombs' impact and within minutes the frail houses of wood and paper were aflame, lighted from the inside like paper lanterns. The hurricane-force wind puffed up great clots of flame and sent burning planks planing through the air to fell people and set fire to what they touched. Flames from a distant cluster of houses would suddenly spring up close at hand, traveling at the speed of a forest fire. Then screaming families abandoned their homes; sometimes the women had already left, carrying their babies and dragging crates or mattresses. Too late: the circle of fire had closed off their street. Sooner or later, everyone was surrounded by fire. [Sources: Eyewitness to History.com; “I Saw Tokyo Burning “ by Robert Guillain 1981; “Blankets of Fire: US. Bombers over Japan During World War II “ by Kenneth Werrell, 1996]

The police were there and so were detachments of helpless firemen who for a while tried to control the fleeing crowds, channeling them toward blackened holes where earlier fires had sometimes carved a passage. In the rare places where the fire hoses worked - water was short and the pressure was low in most of the mains - firemen drenched the racing crowds so that they could get through the barriers of flame. Elsewhere, people soaked themselves in the water barrels that stood in front of each house before setting off again. A litter of obstacles blocked their way; telegraph poles and the overhead trolley wires that formed a dense net around Tokyo fell in tangles across streets. In the dense smoke, where the wind was so hot it seared the lungs, people struggled, then burst into flames where they stood. The fiery air was blown down toward the ground and it was often the refugees' feet that began burning first: the men's puttees and the women's trousers caught fire and ignited the rest of their clothing.

Proper air-raid clothing as recommended by the government to the civilian population consisted of a heavily padded hood over the head and shoulders that was supposed chiefly to protect people's ears from bomb blasts-explosives, that is. But for months, Tokyo had mostly been fire-bombed. The hoods flamed under the rain of sparks; people who did not burn from the feet up burned from the head down. Mothers who carried their babies strapped to their backs, Japanese style, would discover too late that the padding that enveloped the infant had caught fire. Refugees clutching their packages crowded into the rare clear spaces - crossroads, gardens and parks - but the bundles caught fire even faster than clothing and the throng flamed from the inside.

Hundreds of people gave up trying to escape and, with or without their precious bundles, crawled into the holes that served as shelters; their charred bodies were found after the raid. Whole families perished in holes they had dug under their wooden houses because shelter space was scarce in those overpopulated hives of the poor; the house would collapse and burn on top of them, braising them in their holes. [Ibid]

The fire front advanced so rapidly that police often did not have time to evacuate threatened blocks even if a way out were open. And the wind, carrying debris from far away, planted new sprouts of fire in unexpected places. Firemen from the other half of the city tried to move into the inferno or to contain it within its own periphery, but they could not approach it except by going around it into the wind, where their efforts were useless or where everything had already been incinerated. The same thing happened that had terrorized the city during the great fire of 1923: ...under the wind and the gigantic breath of the fire, immense, incandescent vortices rose in a number of places, swirling, flattening sucking whole blocks of houses into their maelstrom of fire. [Ibid]

Wherever there was a canal, people hurled themselves into the water; in shallow places, people waited, half sunk in noxious muck, mouths just above the surface of the water. Hundreds of them were later found dead; not drowned, but asphyxiated by the burning air and smoke. In other places, the water got so hot that the luckless bathers were simply boiled alive. Some of the canals ran directly into the Sumida; when the tide rose, people huddled in them drowned. In Asakusa and Honjo, people crowded onto the bridges, but the spans were made of steel that gradually heated; human clusters clinging to the white-hot railings finally let go, fell into the water and were carried off on the current. Thousands jammed the parks and gardens that lined both banks of the Sumida. As panic brought ever fresh waves of people pressing into the narrow strips of land, those in front were pushed irresistibly toward the river; whole walls of screaming humanity toppled over and disappeared in the deep water. Thousands of drowned bodies were later recovered from the Sumida estuary.

Sirens sounded the all-clear around 5 A.M. - those still working in the half of the city that had not been attacked; the other half burned for twelve hours more. I talked to someone who had inspected the scene an March 11. What was most awful, my witness told me, was having to get off his bicycle every couple of feet to pass over the countless bodies strewn through the streets. There was still a light wind blowing and some of the bodies, reduced to ashes, were simply scattering like sand. In many sectors, passage was blocked by whole incinerated crowds."

Image Sources: National Archives of the United States; Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, Yomiuri Shimbun, The New Yorker, Lonely Planet Guides, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, “Eyewitness to History “, edited by John Carey ( Avon Books, 1987), Compton’s Encyclopedia, “History of Warfare “ by John Keegan, Vintage Books, Eyewitness to History.com, “The Good War An Oral History of World War II” by Studs Terkel, Hamish Hamilton, 1985, BBC’s People’s War website and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2016